7

Informal Caregivers in the United States: Prevalence, Caregiver Characteristics, and Ability to Provide Care

Richard Schulz and Connie A. Tompkins

Informal caregivers are a critical resource to their care recipients and an essential component of the health care system in the United States, yet their role and importance to society as a whole have only recently been appreciated. An informal caregiver, often a family member, provides care, typically unpaid, to someone with whom they have a personal relationship.1 For the last two decades, investigators have endeavored to identify who informal caregivers are, what roles they play in providing care, what needs they have, and what strategies might best support their efforts.

This chapter has three broad goals. One is to describe the prevalence of informal caregiving in the United States by identifying who provides care and to whom that care is provided. The roles and responsibilities of caregivers are discussed next, with a special emphasis on challenges of coordinating care across multiple social and health service organizations to access needed services. This is followed by a discussion of factors that affect the ability to provide care, including the effects of caregiving itself on the ability to perform this role as well as sociodemographic and developmental factors that compromise the ability to provide care. We conclude with a look to the future, which poses formidable challenges to informal caregivers as well as formal health care systems, and we suggest ways in which these challenges might be met.

DIMENSIONS OF INFORMAL CAREGIVING

Prevalence of Caregiving

Rosalyn Carter is often quoted for her observation that “there are only four types of people in the world: (1) those who have been caregivers, (2) those who currently are caregivers, (3) those who will be caregivers, and (4) those who will need caregivers.” There are three distinct groups of informal caregivers, roughly defined by the age of the people they care for: (1) children with chronic illness and disability are typically cared for by young adult parents, (2) adult children with such conditions as mental illness are cared for by middle-aged parents, and (3) older individuals are cared for by their spouses or their middle-aged children. Because the nature of caregiving differs substantially for children and adults, we describe each of these groups separately. We begin with adults, who are by far the largest group of people receiving health-related caregiving.

Caregiving for Adults

There are no exact estimates of the number of informal caregivers in the United States. Prevalence estimates vary widely depending on the definitions used and the populations sampled. At one extreme are estimates that 28.5 percent of the U.S. adult population, or 65.7 million people, provided unpaid care to an adult relative in 2009, with the majority (83 percent) of this care being delivered to people age 50 or older (National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons, 2009). This number, based on the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006), approximates the estimated 59 million adults with a disability in the United States. At the other extreme, data from the National Long-Term Care Survey suggest that as few as 3.5 million informal caregivers provided instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) or activities of daily living (ADLs) assistance to people ages 65 and over (not to all adult care recipients). Intermediate estimates of 28.8 million caregivers (“persons aged 15 or over providing personal assistance for everyday needs of someone age 15 and older”) are reported by the Survey of Income and Program Participation (National Family Caregivers Association and Family Caregiver Alliance, 2006). A recent national survey of individuals ages 45 and older yielded a caregiving rate of 12 percent or 14.9 million adults in that age group (Roth et al., 2009).

These differences are in part attributable to the period of data collection, the age range of the population sampled, the populations targeted, and, most importantly, the definition of caregiving. Thus, the high-end estimates are generated when broad and inclusive definitions of caregiving

are used—for example, “unpaid care may include help with personal needs or household chores. It might be managing a person’s finances, arranging for outside services, or visiting regularly to see how they are doing” (National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons, 2009). Low-end estimates are generated when definitions require the provision of specific ADL or IADL assistance (e.g., Wolff and Kasper, 2006). A related issue is that definitions of caregiving do not clearly distinguish caregiving for chronic disability from caregiving for acute care episodes that might follow a hospitalization event. However, most definitions emphasize chronic disability; intermittent episodes of caregiving are not well represented in the existing data.

Although there are some encouraging signs that age-related disability is declining in the United States, this will be offset by the rapid growth of the senior population to an estimated 70 million in 2035. It is projected that the number of older adults with functional deficits will grow from 22 million in 2005 to 38 million by 2030, assuming no changes in disability rates from current levels (Institute of Medicine, 2007). The challenges posed by this demographic shift will be exacerbated by the decreasing ability of existing formal care systems to care for older adults because of a shortage of nurses and other health care workers and increasing costs of hospitalization and long-term care (Talley and Crews, 2007). Changes in family size and composition and the increased labor force participation of women will make informal caregivers less available. Thus, the convergence of three factors in the decades ahead—increased need for care, decreased availability of formal care, and decreased number of adult children to provide care—have the makings of a perfect storm that will challenge policy makers in the decades ahead.

Finally, recent historical events have added one additional unanticipated caregiving challenge. Young adults are returning from our ongoing wars with multiple, interacting injuries, or polytrauma, which they may be coping with for the rest of their lives. Posttraumatic stress is a common sequel of service in wartime as well. The need for sustained informal caregiving for these young veterans is potentially immense, and the nature of the challenges for their informal caregivers warrants thorough investigation.

Caregiving for Children

All children are care recipients under a broad definition of caregiving. Human beings require nearly two decades to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to function independently. Throughout this developmental period, virtually all children also experience multiple acute illnesses that require support and care from their parents. More extraordinary levels

of care occur when a child suffers from a chronic disability that requires intensive and long-term support from their parents. The 2005-2006 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs estimates that 13.9 percent of children under age 18 have special health care needs, defined in terms of use of services, therapies, counseling, or medications or functional limitations of at least a year in duration (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). According to this survey, 21.8 percent of U.S. households with children include a child with special needs. In some cases, grandparents are the primary caregivers of these children. According to 2000 census data, approximately 2.4 million individuals over age 30 were grandparent caregivers, defined as people who had primary responsibility for coresident grandchildren younger than 18, although it is not known what proportion of these grandchildren had special needs. The prevalence of grandparent caregiving is particularly high among African Americans (4.3 percent age 30 or older) and American Indians and Alaska Natives (4.5 percent) compared with whites (1.1 percent) and Hispanics (2.9 percent) (Simmons and Dye, 2003).

The most prevalent chronic health conditions reported as causing activity limitations among children under age 18 include learning disabilities; attention deficit or hyperactivity disorder; other mental, emotional or behavioral problems; mental retardation or other developmental problems; asthma or breathing problems; and speech or language problems (Institute of Medicine, 2007). These conditions have developmental trajectories such that speech problems are more prevalent at young ages and learning disabilities at later ages. Not included in this list are illnesses or such conditions as childhood cancers, diabetes, heart disease, and cerebral palsy, which are less common among children than adults but create high caregiving demands when present. Other examples of conditions with low prevalence and outsized demands for care and particularly high levels of family stress are autism spectrum disorder and cystic fibrosis.

With the exception of a few selected health conditions, such as spina bifida and neurodevelopment problems resulting from lead exposure, the overall trend in recent decades has been for increased chronic illness, associated disabilities, and the need for sustained care from parents (Zylke and DeAngelis, 2007). These trends have important repercussions for future adult health, as their effects will be felt throughout the remaining life of the affected individual and involved informal caregivers. Multiple factors have contributed to the increased rates of chronic illness and disability in children, including (a) medical advances enabling higher rates of survival of high-risk infants, the increase in multiple births associated with fertility treatments, and the number of infants born prematurely and with low birth weights; (b) increases in diagnosis rates for conditions that cause childhood disability; and (c) increased reporting of disability as a result of enhanced

knowledge among health, education, and social service professionals as well as the general population.

Many children with a disability will carry the burden of chronic illness and disability into middle and old age and require support from informal care providers throughout their lives. This means that some individuals will spend their entire adult lives as caregivers. The ability to survive with disability into late life will add to the already growing number of people who acquire disability as adults, increasing demands for support and care. The growing prevalence of obesity and related disorders among both children and adults in the United States is expected to further raise disability rates and increase the demand for care.

Episodic Caregiving

Because most caregiving data are based on care for chronic illness and disability, little is known about the prevalence of episodic care. Episodic caregiving is typically provided after discharge from an acute care hospital for such events as hip fracture, stroke, cancer, or trauma. In 2007 the United States had nearly 40 million hospital discharges (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2007), and many of these individuals were likely to require care from a family member following discharge. Little is known about the intensity, duration, or type of care provided or about the characteristics of informal caregivers in this instance. Because episodic events are often characterized by acute onset without warning, they entail different challenges than chronic caregiving. Episodic caregivers have to quickly acquire skills related to performing in-home medical procedures, operating medical equipment, monitoring patient status, and coordinating care. Caregivers with limited experience and training may find these challenges overwhelming.

Long-Distance Caregiving

Approximately 15 percent of caregivers to older adults live at least an hour away from their relative and provide care at a distance. Long-distance caregivers tend to be more educated and affluent and are more likely to play a secondary helper role when compared with in-home caregivers. Distant caregivers spend on average 3.4 hours per week arranging services and another 4 hours per week checking on the care recipient or monitoring care. One-third of long-distance caregivers visit at least once a week and provide on average 34 hours of IADL/ADL assistance per month (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2004).

Because distance and time are limiting factors to providing direct support to the recipient, long-distance caregivers have the added challenges of

identifying relevant resources in the recipient’s local environment from a distance, hiring individuals to provide needed care, and monitoring the care providers’ performance as well as the status of the care recipient. From a human factors perspective, performing these tasks requires sophisticated search skills, the ability to screen and evaluate professional care providers, and systems for monitoring care recipient status, which may range from contact via telephone to sophisticated electronic monitoring and communication devices. These caregivers also may have to be able to cope with psychological distress associated with being unable to do more for their distant loved ones who need care.

Characteristics of Informal Caregivers

Nearly everyone serves as an unpaid caregiver at some point in life, and some individuals enact this role over extended periods of time lasting months and often years. Providing care to an individual with chronic illness and disability is generally viewed as a major life stressor, and its effects on the health and well-being of the caregiver have been intensively studied over the last three decades. Because informal caregivers are often called on to provide highly demanding and complex care over long periods of time, the question inevitably arises: Who ends up in this role and how able are they to address care recipients’ needs?

Relatively few population-based studies have been carried out to characterize the population of caregivers. One of the most comprehensive national caregiving studies to date (National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons, 2009) estimates that among adults ages 18 and over, 28.5 percent, or 65.7 million individuals, provide unpaid care in any given year to an adult family member or friend who is also age 18 or older. The typical caregiver in the United States is a 48-year-old woman, has some college education, works, and spends more than 20 hours per week providing unpaid care to her mother. And 66 percent of caregivers are women, and most work either full or part-time (59 percent). The education level of caregivers is slightly higher than that of the U.S. adult population, with more than 90 percent having completed high school and 43 percent being college graduates (compared with 85 percent and 27 percent, respectively) (Stoops, 2004).

Although caregivers are predominantly middle-aged or older, there is growing recognition that even children can be cast in the caregiver role. As many as 1.4 million children in the United States between the ages of 8 and 18 provide care for an older adult. These caregiving children are more likely to come from households with lower incomes, are less likely to live in a two-parent home, and are more likely to experience depression and anxiety when compared with their noncaregiving counterparts (Levine et al., 2005).

Care recipients are typically female (66 percent) and older (80 percent are age 50 or older), and their main presenting problems or illnesses are “old age” (12 percent) followed by Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia (10 percent), cancer (7 percent), mental/emotional illness (7 percent), heart disease (5 percent), and stroke (5 percent). Among younger care recipients (ages 18-49), the primary health problem requiring assistance is mental illness or depression (23 percent). Caregivers provide assistance with a wide range of IADLs, including help with transportation (83 percent), housework (75 percent), grocery shopping (75 percent), and preparing meals (65 percent). And 56 percent of all caregivers also provide ADL assistance, primarily helping the care recipient to get into and out of bed (40 percent), dress (32 percent), and bathe (26 percent). The average length of time caregivers report providing care is 4.6 years (National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons, 2009).

Much less is known about the informal caregivers of children. The National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs indicates that 10 percent of family caregivers spend more than 11 hours each week arranging, coordinating, and providing care and that 24 percent of caregivers either quit working or cut back their hours at work, creating financial problems for their families. The most common types of assistance provided to children with special needs include monitoring the child’s condition (85 percent); ensuring that others (e.g., child’s teachers) know how to deal with the child (84 percent); advocating on his or her behalf to schools, government agencies, or other care providers (72 percent); performing emotional or behavioral treatments or therapies (6 percent); and giving medications (64 percent) (National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons, 2009).

ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF CAREGIVERS

The delivery of effective health-related care in the home requires caregivers to play multiple roles. To varying degrees, caregivers must communicate and negotiate with family members about care decisions, provide companionship and emotional support, interact with physicians and other health care providers about patient status and care needs, drive care recipients to appointments, do housework, shop, complete paperwork and manage finances, hire nurses and aides, help with personal care and hygiene, lift and maneuver the care recipient, and assist with complex medical and nursing tasks (e.g., infusion therapies, tube feedings, medication monitoring) necessitated by the care recipient’s health condition. In addition, caregivers are also called on to coordinate services from health and human service agencies, to make difficult decisions about service needs, and to figure out how to access needed services. Inasmuch as caregiving tasks are physically,

cognitively, and emotionally demanding, individuals who are cast in the caregiving role who are older, have low income, and are chronically ill or disabled will be particularly vulnerable to adverse outcomes.

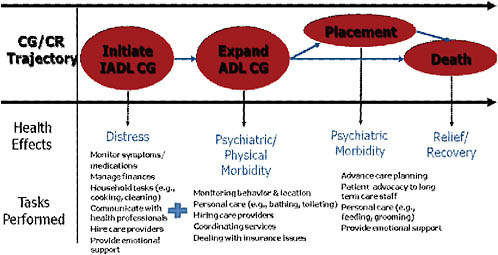

Figure 7-1 illustrates a typical caregiving trajectory involving an older individual with disability living in the community. Caregiving often begins when that individual is no longer able to perform IADL tasks, such as cooking, cleaning, or managing finances, because of a chronic health condition. Thus, the early stages of a caregiving career involve such tasks as monitoring symptoms and medications, helping with household tasks and finances, providing emotional support, and communicating with health professionals. As the health condition of the care recipient worsens and disabilities increase, the caregiver typically provides assistance with ADL tasks, such as dressing, bathing, ambulating, and toileting. Caregivers may also be required to closely monitor the care recipient’s activity in order to ensure his or her safety.

It is important to note that the tasks performed by caregivers are cumulative. Thus, at this stage in a caregiving career, caregivers typically help with ADL tasks in addition to the tasks they performed earlier. For some caregivers, the need for care exceeds their ability to provide it, resulting in the placement of the care recipient into a long-term care facility, but even under these circumstances, caregiving does not end. Many caregivers continue to provide high levels of ADL assistance (e.g., feeding, grooming) to their institutionalized relative, and they must in addition acquire new

FIGURE 7-1 Caregiver health effects and task demands at different stages of the caregiving career.

skills associated with navigating long-term care systems. Given the demands and duration of long-term caregiving, it should come as no surprise that some caregivers may experience relief when the care recipient dies (Schulz et al., 2003).

Effective caregiving requires skills in multiple domains that vary as a function of the underlying illness or chronic condition, type of disability, and age of the care recipient. Both generic and disease-specific caregiving task lists are reported in the literature (Chen et al., 2007; Pakenham, 2007; Horsburgh et al., 2008; Wilkins, Bruce, and Sirey, 2009). From a human factors perspective, the level of specificity in describing these tasks is limited. For example, a typical list might describe tasks broadly, such as monitoring symptoms, providing emotional support, helping with transportation, assisting the patient with body cleaning routines, and so on (Chen et al., 2007; Wilkins et al., 2009). A few researchers have attempted to decompose these global descriptions into constituent components. For example, bathing subtasks might include obtaining supplies, taking off clothes, adjusting water, helping into the tub, getting into bathing position, washing body, leaving bathing position, helping out of the tub, drying body, and getting dressed (Naik, Concato, and Gill, 2004). Even more fine-grained analyses to task decomposition, characteristic of human factors approaches to task analysis, are relatively rare in this literature (e.g., Clark, Czaja, and Weber, 1990). Such human factors analyses of caregiving tasks could greatly benefit the development of robotic and other technologies to assist individuals with disabilities.

Coordinating Care

One of the biggest difficulties facing informal caregivers is the coordination of services to support care recipients in the home or as they transition from one care setting to another. Caregivers may need to negotiate roles among family members who disagree on care options, identify relevant available services, assess eligibility requirements, and communicate and negotiate with health professionals and insurance companies. Even seasoned health professionals with detailed knowledge of and experience with health care systems find care coordination for care recipients a formidable challenge.

Coordinating care is particularly problematic for caregivers providing support to older individuals. The spectrum of formal support options available to care recipients and caregivers is broad, complex, and disorganized, with different access points and eligibility criteria. Access to information about options for care, such as respite services, adult day care, support groups, meals on wheels, transportation services, and financial help, is one of the major unmet needs of informal caregivers (National Alliance for

Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons, 2004). This is particularly problematic among African American, Asian American, and Hispanic caregivers, who are much more likely than white caregivers to say they need help obtaining, processing, and understanding health information (National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons, 2004).

Low-health literacy—that is, deficiencies in the ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and service needs in order to make appropriate health decisions—is associated with poverty, limited education, minority status, immigration, and older age. Results from a recent national survey in the United States suggest that 36 percent of the adult population have limited health literacy skills (National Center for Education Statistics, 2006), which have been consistently associated with poorer health outcomes (i.e., poorer disease management) and increased rates of hospitalization and mortality (Kripalani et al., 2006; Hironaka and Paasche-Orlow, 2008).

The magnitude of care coordination challenges was recently demonstrated in a study to evaluate the ability of relatively well-educated adults with computer experience to use the Medicare.gov website to make decisions about eligibility for services and prescription drug plans (Czaja, Sharit, and Nair, 2008). Participants were asked to determine eligibility for home health care services, select a home health agency to meet specified needs, make decisions about enrollment in Medicare Part D, and select a drug plan and determine associated costs based on a specified medication regime. Most participants were unable to specify all eligibility criteria for home health services (68.8 percent), choose the correct home health agency (80.4 percent), or execute computation procedures needed for making a plan enrollment decision (83.9 percent).

To help address the need for coordinated and comprehensive care, one-stop service programs, such as Child’s Way and the Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), have been developed to provide integrated and seamless total care, including both social and medical services. These programs, however, have eligibility criteria that make them inaccessible to the majority of individuals with chronic disability and their caregivers (e.g., for Child’s Way a participant must be age 8 or younger, have a chronic illness with long-term medical needs, and qualify for in-home services; for PACE the participant must be age 55 or older and meet criteria for nursing facility level of care). Thus the need in this area remains great.

In sum, the complexity of identifying and accessing health and social service options that might be useful to caregivers is daunting even to experienced health professionals cast in an informal caregiving role. The average lay person has little chance of optimizing formal support services to minimize the burdens of caregiving.

Assessment, Training, and Monitoring of Caregiver Performance

Systematic assessment of individuals with chronic health conditions or disability occurs routinely in medical, health, and social service settings. However, assessment of informal caregivers’ needs and capabilities is rare. Caregiver assessment is an essential requisite for optimizing care recipient functioning and caregiver well-being. There is strong consensus among community service providers, clinicians, and researchers that caregivers should be assessed, not only to determine eligibility for services but also to gauge their capacity to provide the care required by the care recipient. Although this view is widely endorsed, its implementation is highly variable in the United States. Few federal or state home- or community-based services programs uniformly assess the informal caregiver’s well-being and needs for support. To help address these gaps, the National Center on Caregiving at the Family Caregiver Alliance convened a national consensus development conference in 2005 to generate principles and guidelines for caregiver assessment (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2006a, 2006b). The resulting guidelines address the methods and goals of caregiver assessment in detail, including the recommendation that government and other third-party payers should recognize and pay for caregiver assessment as a routine part of care for older people and individuals with disability. To date, few of the conference recommendations have been implemented, although issues of informal caregiving have become part of the health care reform debate in the United States.

Turning to caregiver training, knowledge about chronic illness and disability, how to provide care, and how to access and utilize services is another requisite to effective caregiving. Caregivers who do not know the difference between stroke and Alzheimer’s disease, for example, and the differential trajectories of these conditions, are unlikely to know which types of services are appropriate and available, or how to access them.

Interventions designed to diminish caregiver burden invariably include education and training to help the caregiver understand the nature of a particular disease, its symptoms, and its progression. Such education is often complemented with referral resources that provide additional information and services relevant to a particular health condition. Numerous intervention studies have shown that the ability to cope with the challenges of caregiving in chronic illness is enhanced by skills training that helps the caregiver to better monitor the care recipient’s behavior and the progression of the disease and to provide appropriate assistance.

One recent randomized clinical trial demonstrated the efficacy of a caregiver psychoeducational intervention on quality of life in multiple domains among white, African American, and Hispanic caregivers of individuals with dementia (Belle et al., 2006). Other psychoeducational inter-

vention studies, focusing on environmental modifications (Gitlin et al., 2009), found that providing caregiver counseling (Mittelman et al., 2007) can reduce burden and delay institutionalization of the care recipient. Finally, there is increasing recognition that caregivers and care recipients reciprocally affect each other. This perspective has led to the development of interventions that simultaneously treat the caregiver and the care recipient, with the aim of showing that dual treatment psychoeducational approaches are superior to treatments that focus on the caregiver only (Schulz et al., 2009a). In sum, recent studies demonstrate that education and training are valuable tools in enhancing caregiver functioning, but they have not yet been widely implemented in community settings. Efforts are currently under way to translate this research into community applications (see Burgio et al., 2009).

Monitoring of caregiver performance is a neglected area among both researchers and clinicians. With few exceptions (Gitlin et al., 2003), intervention studies that provide skills training to caregivers rarely assess the extent to which the intended skills are effectively implemented outside the treatment sessions, whether the learned skills are useful for newly emerging caregiver challenges, or how long skills learned as part of an intervention are used after the intervention is terminated. Similarly, clinicians who educate caregivers about how to provide care to the recipient rarely assess quality and appropriateness of caregiving outside the training session. For some types of care, patient status may be used as a proxy for caregiver performance, but this does not guarantee that the care provided by the caregiver was delivered as intended or was effective.

Technology has the potential of improving both the training and monitoring of caregivers. Websites that provide information about medical conditions and caregiving have become valuable resources to the discerning consumer who can filter the vast amounts of information available. Computers have also been used to deliver training programs and provide individualized support to caregivers (Smith, 2008). Numerous web-based support programs are available for caregivers. For example, the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS) advises caregivers by e-mail, conducts assessments by web camera, and models caregiving procedures in video clips (Glasgow, 2007; Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System, 2008). To be effective, the available information has to be accessible in its organization and layout, the complexity of language and visual images, and ease of interface.

Monitoring technologies that provide remote access to care recipient status have become important aids to caregivers and clinicians. What has not yet been realized is the use of online monitoring devices, such as embedded sensor systems and video cameras that would enable clinicians to infer or observe the delivery of care to the care recipient and provide real-time

corrective guidance as needed. Although episodic monitoring is currently used in some telehealth systems that enable a care recipient–caregiver dyad to remotely check in with a health care professional, more continuous monitoring of caregiver performance and provision of real-time instruction or guidance have not been implemented. Many such technologies raise privacy concerns that may make them difficult to put into practice. Recent research in this area suggests that with increasing levels of disability, individuals receiving care become more willing to relinquish privacy for increased functioning and independence (Beach et al., 2009). However, little is known about caregivers’ willingness to be monitored and remotely guided by health care professionals.

ABILITY TO PROVIDE CARE

What factors affect caregivers’ ability to provide care? The answer to this question requires keeping in mind both who occupies the caregiving role and how the experience of caregiving itself affects the ability to provide care, especially over the long haul. One can anticipate that the increasingly compromised health status of chronically stressed caregivers diminishes their capacity to provide care. In addition, subgroups of individuals defined by race, economic status, education, and age vary in their capacity to provide care.

Health Effects of Caregiving

Several recent reviews document the link between caregiving and health (Pinquart and Sörensen, 2003b, 2007; Vitaliano, Zhang, and Scanlan, 2003; Gouin, Hantsoo, and Kiecolt-Glaser, 2008). For example, Vitaliano and colleagues (2003) reviewed 23 studies to compare the physical health of dementia caregivers with demographically similar noncaregivers, and across 11 health categories caregivers exhibited a least a slightly greater risk of health problems than did noncaregivers. Tables 7-1 and 7-2 summarize the wide range of outcome variables represented in the literature. Each of these variables has been linked to such stressors as the duration and type of care provided and functional and cognitive disabilities of the patient, as well as secondary stressors, such as finances and family conflict. As a result of these stressors, providing care has been shown to affect psychological well-being, health habits, physiological responses, psychiatric and physical illness, and mortality (Quittner, Glueckauf, and Jackson, 1990; Schulz, Visintainer, and Williamson, 1990; Schulz et al., 1995; Schulz and Quittner, 1998; Schulz and Beach, 1999; Pinquart and Sörensen 2003a, 2003b, 2007; Vitaliano et al., 2003; Epel et al., 2004; Christakis and Allison, 2006).

TABLE 7-1 Physical Health Effects of Caregiving

|

Type of Measure |

Specific Indicators |

Comments |

|

Global Health |

|

|

|

|

Self-reported health (current health, health compared with others, changes in health status) Chronic conditions (chronic illness checklists) Physical symptoms (Cornell Medical Index) Medications (number and types) Health service utilization (clinic visits, days in hospital, physician visits) Mortality |

Overall, effects are small. Self-report measures are most common and show largest effects. One prospective study reports increased mortality for strained caregivers when compared with noncaregivers. Higher age, lower socioeconomic status, and lower levels of informal support related to poorer health. Greater negative effects found for dementia vs. nondementia caregivers and spouses vs. nonspouses. |

|

Physiological |

|

|

|

|

Antibodies and functional immune measures (immunoglobulin, Epstein Barr virus, T-cell proliferation, responses to mitogens, response to cytokine stimulation, lymphocyte counts) Stress hormones and neurotransmitters (ACTH, epinephrine, norepinephrine, cortisol, prolactin) Cardiovascular measures (blood pressure, heart rate) Metabolic measures (body mass, weight, cholesterol, insulin, glucose, transferin) Speed of wound healing |

Effect sizes for all indicators are generally small. Stronger relationships found for stress hormones and antibodies than other indicators. Evidence linking caregiving to metabolic and cardiovascular measures is weak. Men exhibit greater negative effects on most physiological indicators. |

|

Health Habits |

|

|

|

|

Sleep, diet, exercise Self-care, medical compliance |

|

Measures of psychological well-being, such as depression, stress, and burden, have been most frequently studied in the caregiving literature and generally yield consistent and relatively large health effects (Schulz et al., 1995, 1997; Teri et al., 1997; Marks, Lambert, and Choi, 2002; Pinquart and Sörensen, 2003b). These effects are moderated by age, socioeconomic status (SES), and the availability of social support such that

TABLE 7-2 Psychological Health Effects of Caregiving

|

Type of Measures |

Specific Examples |

Comments |

|

Depression |

Clinical diagnosis, symptom checklists, antidepressant medication use |

Most frequently studied caregiver outcomes with largest effects. Greater negative effects found for dementia vs. nondementia caregivers. Higher age, lower seociecomonic status, and lower levels of informal support related to poorer mental health. |

|

Anxiety |

Clinical diagnosis, symptom checklists, anxiolytic medication use |

|

|

Stress |

Burden |

|

|

Subjective Well-Being |

Global self-ratings; global quality of life ratings |

|

|

Positive Aspects of Caregiving |

Self-ratings of benefit finding |

|

|

Self-Efficacy |

Self-ratings |

older caregivers, with low SES and small support networks, report poorer psychological health than caregivers who are younger and have more economic and interpersonal resources (Vitaliano et al., 2003).

Detrimental physical health effects of caregiving are generally smaller, regardless of how they are measured (Vitaliano et al., 2003; Pinquart and Sörensen, 2007). Although relatively few studies have focused on the association between caregiving and health habits, researchers have found evidence for impaired health behaviors among caregivers engaged in heavy-duty caregiving (Schulz et al., 1997; Burton et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2003; Matthews et al., 2004).

While these findings are robust across many studies, one should be cautious about attributing poor health status to caregiving per se. Differences in illness rates between caregivers and noncaregivers may reflect differences that existed prior to taking on the caregiving role. For example, low-SES individuals are more likely to take on the caregiving role than high-SES ones (National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons, 2004), and low SES is also a risk factor for poor health status. Higher rates of illness in spousal caregivers also may be the result of assortative mating (people tend to choose others who are similar to them) and of shared health habits (e.g., diet, exercise) and life circumstances (e.g., access to medical care, job stress).

Prospective studies that link caregiver health declines to increasing care demands provide more compelling evidence of the health effects of caregiving (Shaw et al., 1997; Schulz and Beach, 1999). A handful of studies have followed samples of noncaregivers until they become caregivers and compared them with those who do not take on the caregiving role (Lawton et al., 2000; Seltzer and Li, 2000; Burton et al., 2003; Hirst, 2005). Burton and colleagues (2003) and more recently Hirst (2005) provide compelling evidence that moving into a demanding caregiving role, defined as providing assistance with basic ADL for 20 hours or more of care per week, results in increased depression and psychological distress, impaired self-care, and lower self-reported health. Findings on the effects of transitioning out of the caregiving role because of patient improvement, institutionalization, or death help to complete the picture on the association between caregiving and health. Improved patient functioning is associated with reductions in caregiver distress (Nieboer et al., 1998), and the death of the care recipient has been found to reduce caregiver depression, enabling them to return to normal levels of functioning within a year of the patient’s death (Schulz et al., 2003).

The prevalence of depressive symptoms, clinical depression, and reduced quality of life among caregivers suggests that caregiving is an important public health issue in the United States. This is particularly important because depression is the second leading cause of disability worldwide (Talley and Crews, 2007). Moreover, even if the detrimental effects of caregiving on physical health are relatively small, the large and increasing number of people affected means that the overall impact is significant. Recognition of these facts and the knowledge that caregivers represent a major national health resource has resulted in national policy, such as the National Family Caregiver Support Program. However, most advocates for caregivers feel that existing programs fall far short of what is needed (Riggs, 2003-2004).

With regard to the impact these health effects have on the ability to perform caregiving tasks, multiple factors should be considered. As noted earlier, about two-thirds of all caregivers report stress or strain associated with the caregiving role (Schulz et al., 1997; Roth et al., 2009). Decades of laboratory research have demonstrated the detrimental effects of stress on attention, memory, perceptual motor performance, and judgment and decision making (Staal, 2004). The relevance of these findings to real-world settings has been questioned, because experimental stressors typically are of short duration, are often novel, are limited in intensity, and usually do not have long-term adverse effects. Real-world stressors tend to be more severe, recurrent or continuous, and typically have long-term negative effects on the individual.

Small-sample studies on chronic stress and cognition suggest decrements in executive functioning, especially attentional control, and in prospective

memory (Ohman et al., 2007), as well as slow short-term/working memory processing, especially when attention is divided (Brand, Hanson, and Godaert, 2000). The relationship between cognitive performance and the chronic stress induced by caregiving, however, is clearly multifactorial. For example, a decline in receptive vocabulary over two years in spousal caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease was mediated by metabolic risk (a composite measure of obesity plus insulin use) and hostile attribution (Vitaliano et al., 2005). In another example with the same population, caregiver status alone did not account for decrements in complex attention and speed of information processing (Caswell et al., 2003). Rather, within the caregiver sample, these decrements were predicted by higher levels of distress and lower perceptions of the quantity of positive experiences in life.

Another consideration is that the effects of stress are likely to be exacerbated among individuals with limited cognitive and physical reserve, as is most likely the case with older spousal caregivers. This argues for screening strategies that would assess potential moderators of the stress response, such as education, cognitive ability, physical status, traits that may make people particularly vulnerable to chronic stress, and subjective/emotional perceptions of stress and social support, in addition to levels of stress per se. Such information could be used to decide what types of tasks can be assigned to caregivers as well as how closely to monitor caregiver performance.

Along with high levels of stress, many caregivers also report high levels of depressive symptoms. For example, among caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, nearly half of all caregivers report depressive symptoms high enough to place them at risk for clinical depression (e.g., Belle et al., 2006). Depression has both motivational and performance consequences and has been linked to impaired role functioning, particularly roles associated with work, home, social relationships, and close relations (Druss et al., 2009). Depression can erode the social support needed to provide effective care and can isolate the caregiver from important sources of emotional and informational support.

Depression in spousal caregivers is also a risk factor for potentially harmful caregiver behaviors, defined as psychological (e.g., screaming, threatening with nursing home placement) and physical mistreatment of the care recipient (e.g., withholding food, hitting or slapping, shaking) (Beach et al., 2005). Caregiver cognitive status and physical symptoms were also independent risk factors associated with care recipient mistreatment, suggesting that caregivers should be assessed on these dimensions as well. The literature does not provide clear guidelines regarding threshold values in these domains; higher levels of impairment are generally associated with higher rates of potentially harmful behaviors. In general, clinicians should

be cautious about assigning caregiving responsibilities to individuals who exhibit high levels of depressive symptoms or cognitive and physical impairments that are unusually severe for their age group.

Sociodemographic Factors

As alluded to earlier, caregivers as a group, compared with non-caregivers, are characterized by sociodemographic risk factors that may affect their ability to provide effective care as well as increase their vulnerability to the detrimental health effects of caregiving. They tend to be of lower socioeconomic status, and the proportion of people involved in caregiving is higher among African Americans and Hispanics than whites (Roth et al., 2009). Caregivers tend to have fewer friends in their social networks, and older spousal caregivers tend to be physically more compromised than spouses who are not providing care (Schulz et al., 1997). In absolute terms, the magnitude of the differences between caregiver and comparable non-caregiver populations is not large, but these differences may compromise the ability to provide high levels of care over extended periods of time.

Inasmuch as health, well-being, and socioeconomic status are closely intertwined, researchers have become interested in the effects of combining employment and caregiving. Middle-aged women at the peak of their earning power, many of whom are employed, provide the majority of care to older disabled relatives (see Schulz and Martire, 2009, for a review). The increasing labor force participation of women, along with increasing demands for care, raise important questions about how effectively and at what cost the roles of caregiver and employee can be combined. Recent findings indicate that elder caregiving has both short-term and long-term economic impacts on female caregivers. Low levels of caregiving demand (e.g., 14 hours or less per week) can be absorbed by employed caregivers with little impact on labor force participation. However, heavy caregiving demands (e.g., 20 hours or more per week) result in significant work adjustment, involving either reduced hours or leaving a job altogether, and associated declines in annual incomes. Women with less than a high school education are most vulnerable to these negative effects. These short-term effects increase the probability of long-term negative impacts in the form of lower economic and health status of the caregiver. The long-term impacts may in part be attributable to the difficulty of reentering the labor force.

Developmental Declines

From a human factors perspective, developmental declines have important implications for the ability to provide care as well as the design of systems that might support caregivers. Sensory decline is common in

middle-aged and older adults. For example, measured hearing loss is present in about 44 percent of adults ages 60-69, with prevalence increasing with age (Cruickshanks et al., 1998; Pratt et al., 2009). Hearing is particularly impaired in difficult listening environments, such as those with background noise or reverberation or when communication is rapid. For individuals with age-related hearing loss, attempts to comprehend spoken language can involve substantial perceptual and cognitive effort that may detract from other aspects of cognitive performance (Wingfield, Tun, and McCoy, 2005). While hearing can be improved with hearing aids or other assistive listening devices, these devices do not completely correct the typical age-related hearing loss. The devices may be abandoned because they are uncomfortable to use or perceived as ineffective. In addition, many people do not seek help for hearing loss, complaining, for example, that the people around them just talk too softly. When interacting with caregivers, it is crucial to consider their ability to perceive spoken information, and providers of that information must be aware that just talking louder will not address a speech perception problem. Visual impairment also may be a problem for older caregivers, making it difficult for them to read medication labels or other instructional materials.

Age-related declines in strength and mobility may also affect the ability to provide care. One of the hallmarks of aging is the reduction in mobility resulting in part from declining muscle mass, increased fat infiltration into muscles and decreased strength (Visser et al., 2005). As a result, older female caregivers, in particular, may be unable to carry out tasks requiring lifting heavy objects (e.g., helping their husband out of a chair) or may risk back injury or injury to the care recipient if they attempt these tasks. Essential tremor, a disorder characterized by kinetic arm tremor, is also associated with increasing age (Benito-León and Louis, 2006) and may make it difficult for caregivers to execute fine-grained motor tasks, such as giving injections or handling pills.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Informal caregiving is a central feature of the health care landscape and will become even more prominent in the decades ahead. The demand and need for care will increase dramatically over the next three decades as a result of the aging of the population, infant and childhood survival, health behaviors that increase disabling health conditions such as obesity, and returning war veterans suffering from polytrauma. This will happen in a context in which the availability of informal support is declining, the costs of formal care and support are already too high and unsustainable, and there is a growing shortfall of health care professionals with relevant expertise. Resolving this supply–demand dilemma will require efficiencies

in both informal and formal health care systems that greatly exceed current practice. Important research and policy issues need to be addressed before progress can be made on this agenda. We present below five recommendations that, though by no means exhaustive, should receive high priority.

-

Adopt a standard definition of what it means to be an informal caregiver and use it consistently in surveys of the U.S. population, in order to accurately assess the prevalence of caregiving, the public health burden associated with caregiving, and a full range of issues such as those discussed here. Accurate and consistent data are needed on who is providing care, what types of care are provided, for how long, at what costs to the caregiver, and the probable downstream costs to society. Having such data is an important requisite to developing policy on support programs for caregivers. The value of this recommendation is evident, for example, in Australia, Japan, and the United Kingdom, all of which have adopted standard definitions of caregiving that are linked to eligibility for caregiver and care recipient services. Variations of the standard definition may be necessary for different populations of caregivers and care recipients, and levels of care should also be consistently defined.

-

Better coordination is needed between formal and informal health care systems to ensure a close match between home care demands and the informal caregiver’s ability to provide that care. This will require a clear understanding of the task demands of home care and an assessment of caregiver capabilities, including their motivation to provide care, their physical, sensory, motor, and cognitive ability to perform caregiving tasks, their levels of distress and depression, and the quantity and quality of other support available to them. Assessments of the caregiver should be a routine feature during care recipient and health care provider encounters, and these data should inform decisions about whether a caregiver is capable of taking on the caregiver role, the types of training needed, and the intensity of monitoring and external support required to ensure adequate care that does not unduly compromise the caregiver’s own functioning. A related need concerns the development of decision rules for terminating caregiving responsibilities when caregivers are no longer able to carry out their assignments. Implementing these strategies will require expansion of the training of health care and social service providers to give them the skills and tools to carry out these types of assessments (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2006a, 2006b). Detailed recommendations on who should do assessments, what should be assessed, and when and where, are available from

-

the National Consensus Development Conference on Caregiver Assessment (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2006a, 2006b). Although intended for caregivers of older care recipients, these recommendations serve as a good starting point for developing assessment procedures and tools for all caregiving populations.

-

From a scientific perspective, there remain important unanswered questions about caregiving that have far-reaching policy implications. For example, a deeper understanding is needed of what causes distress in the caregiving experience and how best to help the caregiver. Although numerous studies point to the importance of various functional disabilities and associated care demands as causes of caregiver burden, the role that such factors as the care recipient’s suffering play in the life of a caregiver may be underestimated. Making these distinctions is important because it may lead to different policy responses (e.g., providing respite to ease the burdens of care provision as well as treatments to decrease the suffering of the care recipient or to help the caregiver come to terms with the suffering of their loved one) (Monin and Schulz, 2009).

-

Technology has the potential of increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of formal and informal care providers, enhancing the functioning and autonomy of individuals with disability, preventing premature decline, and generally enhancing the quality of life of elders. Implementing technology-based solutions will require the development of user-friendly and highly reliable systems that are able to both identify needs and respond to them. Considerable progress has been made in recent years in developing and deploying sensing and monitoring technology useful in identifying individuals experiencing or at risk for adverse outcomes. Computer, sensing, and communication technologies have also been effectively used for caregiver training and performance monitoring. Research on enabling technologies that extend the functional capability of humans is still in the early stages of development and should receive high priority.

-

Because caregiving is so prevalent in U.S. society and integral to the health and well-being of the population, all adults need to be educated about the likelihood of becoming a caregiver and a care recipient, the roles and responsibilities of caregiving, and rudimentary caregiving skills. A recent survey of 1,018 adults ages 18 and over (Schulz et al., 2009b) found that adults have realistic expectations about becoming caregivers in the future but are less able to see themselves as care recipients. Nearly two-thirds of U.S. adults expect to be caregivers in the future, but nearly half believe that they won’t need any care in the future. Indeed, more than one-third

-

of adults have never thought about needing care in the future, and few have made any preparations for future care, such as talking with family or friends about care needs in the future (34 percent), setting aside funds to cover additional expenses (41 percent), signing living wills or health care power of attorney (40 percent), or purchasing disability or long-term care insurance. When asked how prepared they are to provide care to others, the majority (56 percent) were unprepared to carry out basic caregiving tasks, such as bathing, dressing, and toileting, 35 percent said they were only somewhat or not at all (28 percent) prepared to handle health insurance matters, 56 percent said they were unprepared to assist with medications, and most worry about handling financial matters for a loved one. These data suggest that caregiving and care receiving should be a normative component of adult education. The goal of such efforts should be to inform adults about the likelihood of caregiving and care receiving, ways in which one can plan for these eventualities, and rudimentary skills needed to perform or cope in these roles.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Richard Schulz is director of the Center for Social and Urban Research at the University of Pittsburgh. His work has focused on social-psychological aspects of aging, including the role of control as a construct for characterizing life-course development and the impact of disabling late-life disease on patients and their families. Connie A. Tompkins is professor of communication science and disorders in the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research focuses on the cognitive and psycholinguistic bases of neurologically based communication disorders.

REFERENCES

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2007). Acute care/hospitalization: Studies suggest ways to improve the hospital discharge process to reduce postdischarge adverse events and rehospitalizations. Available: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/dec07/1207RA12.htm [accessed June 2010].

Beach, S., Schulz, R., Downs, J., Matthews, J., Barron, B., and Seelman, K. (2009). Disability, age, and informational privacy attitudes in quality of life technology applications: Results from a national web survey. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing, 2(1), 1-21.

Beach, S.R., Schulz, R., Williamson, G.M., Miller, L.S., Weiner, M.F., and Lance C.E. (2005). Risk factors for potentially harmful informal caregiver behavior. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(2), 255-261.

Belle, S.H., Burgio, L., Burns, R., Coon, D., Czaja, S.J., Gallagher-Thompson, D., Gitlin, L.N., Klinger, J., Koepke, K.M., Lee, C.C., Martindale-Adams, J., Nichols, L., Schulz, R., Stahl, S., Stevens, A., Winter, L., and Zhang, S. [REACH II Investigators]. (2006). Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 145(10), 727-738.

Benito-León, J., and Louis, E.D. (2006). Essential tremor: Emerging views of a common disorder. Nature Clinical Practice, Neurology, 2(12), 666-678.

Brand, N., Hanson, E., and Godaert, G. (2000). Chronic stress affects blood pressure and speed of short-term memory. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 91(1), 291-298.

Burgio, L.D., Collins, I.B., Schmid, B., Wharton, T., McCallum, D., and DeCoster, J. (2009). Translating the REACH caregiver intervention for use by Area Agency on Aging personnel. The Gerontologist, 49(1), 103-116.

Burton, L.C., Zdaniuk, B., Schulz, R., Jackson, S., and Hirsch, C. (2003). Transitions in spousal caregiving. The Gerontologist, 43(2), 230-241.

Caswell, L.W., Vitaliano, P.P., Croyle, K.L., Scanlan, J.M., Zhang, J., and Daruwala, A. (2003). Negative associations of chronic stress and cognitive performance in older adult spouse caregivers. Experimental Aging Research, 29(3), 303-318.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2006). Disability and health state chartbook, 2006: Profiles of health for adults with disabilities. Atlanta: Author.

Chen, H.C., Chen, M.L., Lotus Shyu, Y.I., and Tang, W.R. (2007). Development and testing of a scale to measure caregiving load in caregivers of cancer patients in Taiwan: The care task scale-cancer. Cancer Nursing, 30(3), 223-231.

Christakis, N., and Allison, P.D. (2006). Mortality after the hospitalization of a spouse. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(7), 719-730.

Clark, M.C., Czaja, S.J., and Weber, R.A. (1990). Older adults and daily living task profiles. Human Factors, 32(5), 537-549.

Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System. (2008). What is CHESS? University of Wisconsin-Madison. Available: http://www.engr.wisc.edu/ie/research/centers/chess.html [accessed June 2010].

Cruickshanks, K.J., Wiley, T.L., Tweed, T.S., Klein, B.E., Klein, R., Mares-Perlman, J.A., and Nondahl, D.M. (1998). Prevalence of hearing loss in older adults in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin: The epidemiology of hearing loss study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 148(9), 879-886.

Czaja, S.J., Sharit, J., and Nair, S.N. (2008). Usability of the Medicare health web site. Journal of the American Medical Association, 300(7), 790-792.

Druss, B.G., Hwang, I., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N.A., Wang, P.S., and Kessler, R.C. (2009). Impairment in role functioning in mental and chronic medical disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Molecular Psychiatry, 14(7), 728-737.

Epel, E.S., Blackburn, E.H., Lin, J., Dhabhar, F.S., Adler, N.E., Morrow, J.D., and Cawthon, R.M. (2004). Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(49), 17,312-17,315.

Family Caregiver Alliance. (2006a). Caregiver assessment: Principles, guidelines, and strategies for change. Report from a National Consensus Development Conference (vol. I). San Francisco: Author.

Family Caregiver Alliance. (2006b). Caregiver assessment: Voices and views from the field. Report from a National Consensus Development Conference (vol. II). San Francisco: Author.

Gitlin, L.N., Hauck, W.W., Winter, L., Hodgson, N., and Schinfeld, S. (2009). Long-term effect on mortality of a home intervention that reduces functional difficulties in older adults: Results from a randomized trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57(3), 476-481.

Gitlin, L.N., Winter, L., Corcoran, M., and Hauck, W. (2003). Effects of the home environmental skill-building program on the caregiver-care recipient dyad: Six-month outcomes from the Philadelphia REACH initiative. The Gerontologist, 43(4), 532-546.

Glasgow, R.E. (2007). eHealth evaluation and disseminiation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(5 Supplement), S119-S126.

Gouin, J.P, Hantsoo, L., and Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. (2008). Immune dysregulation and chronic stress among older adults: A review. Neuroimmunomodulation, 15(4-6), 251-259.

Hironaka, L.K., and Paasche-Orlow, M.K. (2008). The implications of health literacy on patient-provider communication. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 93(5), 428-432.

Hirst, M. (2005). Carer distress: A prospective, population-based study. Social Science and Medicine, 61(3), 697-708.

Horsburgh, M.E., Laing, G.P., Beanlands, H.J., Meng, A.X., and Harwood, L. (2008). A new measure of “lay” caregiver activities. Kidney International, 74, 230-236.

Institute of Medicine. (2007). The future of disability in America. Committee on Disability in America, Board on Health Sciences Policy. M.J. Field and A.M. Jette, Eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kripalani, S., Henderson, L.E., Chiu, E.Y., Robertson, R., Kolm, P., and Jacobson, T.A. (2006). Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(8), 852-856.

Lawton, M.P., Moss, M., Hoffman, C., and Perkinson, M. (2000). Two transitions in daughters’ caregiving careers. The Gerontologist, 40(4), 437-448.

Lee, S., Colditz, G., Berkman, L., and Kawachi, I. (2003). Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. women: A prospective study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 24(2), 113-119.

Levine, C., Gibson Hunt, G., Halper, D., Hart, A.Y., Lautz, J., and Gould, D.A. (2005). Young adult caregivers: A first look at an unstudied population. American Journal of Public Health, 95(11), 2071-2075.

Marks, N.E., Lambert, J.D., and Choi, H. (2002). Transitions to caregiving, gender and psychological: A prospective U.S. national study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 657-667.

Matthews, J.T., Dunbar-Jacob, J., Sereika, S., Schulz, R., and McDowell, B.J. (2004). Preventive health practices: Comparison of family caregivers 50 and older. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 30(2), 46-54.

Mittelman, M.S., Roth, D.L., Clay, O.J., and Haley, W.E. (2007). Preserving health of Alzheimer caregivers: Impact of a spouse caregiver intervention. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15, 780-789.

Monin, J.K., and Schulz, R. (2009). Interpersonal effects of suffering in older adult caregiving relationships. Psychology and Aging, 24(3), 681-695.

Naik, A.D., Concato, J., and Gill, T.M. (2004). Bathing disability in community-living older persons: Common, consequential, and complex. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(11), 1,805-1,810.

National Alliance for Caregiving. (2004). Miles away: The MetLife Study of long-distance caregiving. Washington, DC: Author.

National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons. (2004). Caregiving in the U.S., 2004. Washington, DC: Author.

National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons. (2009). Caregiving in the U.S., 2009. Washington, DC: Author.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2006). The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. (NCES 2006-483). M. Kutner, E., Greenberg, Y. Jin, and C. Paulsen, Eds. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

National Family Caregivers Association and Family Caregiver Alliance. (2006). Prevalence, hours, and economic value of family caregiving, updated state-by-state analysis of 2004 national estimates. Kensington, MD and San Francisco: Author.

Nieboer, A.P., Schulz, R., Matthews, K.A., Scheier, M.F., Ormel, J., and Lindenberg, S.M. (1998). Spousal caregivers’ activity restriction and depression: A model for changes over time. Social Science and Medicine, 47(9), 1,361-1,371.

Ohman, L., Nordin, S., Bergdahl, J., Slunga Birgander, L., and Stigsdotter Neely, A. (2007). Cognitive function in outpatients with perceived chronic stress. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment, and Health, 33(3), 223-232.

Pakenham, K.I. (2007). The nature of caregiving in multiple sclerosis: Development of the caregiving tasks in multiple sclerosis scale. Multiple Sclerosis, 13, 929-938.

Pinquart, M., and Sörensen, S. (2003a). Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: A meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 58, P112-P128.

Pinquart, M., and Sörensen, S. (2003b). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 250-267.

Pinquart, M., and Sörensen, S. (2007). Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: A meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 62(2), P126-P137.

Pratt, S.R., Kuller, L., Talbott, E.O., McHugh-Pemu, K., Buhari, A.M., and Xu, X. (2009). Prevalence of hearing loss in black and white elders: Results of the cardiovascular health study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52(4), 973-989.

Quittner, A.L., Glueckauf, R.L., and Jackson, D.N. (1990). Chronic parenting stress: Moderating versus mediating effects of social support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1,266-1,278.

Riggs, J.A. (2003-2004). A family caregiver policy agenda for the twenty-first century. Generations, 27(4), 68-73.

Roth, D., Perkins, M., Wadley, V., Temple, E., and Haley, W. (2009). Family caregiving and emotional strain: Associations with quality of life in a large national sample of middle-aged and older adults. Quality of Life Research, 18(6), 679-688.

Schulz, R., and Beach, S.R. (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282(23), 2,215-2,219.

Schulz, R., and Martire, L.M. (2009). Caregiving and employment. In S.J. Czaja and J. Sharit (Eds.), Aging and work: Implications in a changing landscape. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Schulz, R., and Quittner, A.L. (1998). Caregiving for children and adults with chronic conditions: Introduction to the special issue. Health Psychology, 17(2), 107-111.

Schulz, R., Czaja, S.J., Lustig, A., Zdaniuk, B., Martire, L.M., and Perdomo, D. (2009a). Improving the quality of life of caregivers of persons with spinal cord injury: A randomized controlled trial. Rehabilitation Psychology, 54(1), 1-15.

Schulz, R., Czaja, S.J., Belle, S.H., and Lewin, N. (2009b). Survey of the U.S. adult population on preparedness for caregiving. Unpublished data, University of Pittsburgh.

Schulz, R., Mendelsohn, A.B., Haley, W.E., Mahoney, D., Allen, R.S., Zhang, S., Thompson, L., and Belle, S.H. (2003). End-of-life care and the effects of bereavement on family caregivers of persons with dementia. New England Journal of Medicine, 349(20), 1,936-1,942.

Schulz, R., Newsom, J., Mittelmark, M., Burton, L. Hirsch, C., and Jackson, S. (1997). Health effects of caregiving, the Caregiver Health Effects Study: An ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 19(2), 110-116.

Schulz, R., O’Brien, A.T., Bookwala, J., and Fleissner, K. (1995). Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence, correlates, and causes. The Gerontologist, 35(6), 771-791.

Schulz, R., Visintainer, P., and Williamson, G.M. (1990). Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of caregiving. Journals of Gerontology, 45(5), P181-P191.

Seltzer, M.M., and Li, W. (2000). The dynamics of caregiving: Transitions during a three-year prospective study. The Gerontologist, 40(2), 165-178.

Shaw, W.S., Patterson, T.L., Semple, S.J., Ho, S., Irwin, M.R., Hauger, R.L., and Grant, I. (1997). Longitudinal analysis of multiple indicators of health decline among spousal caregivers. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 19(2), 101-119.

Simmons, T., and Dye, J.L. (2003). Grandparents living with grandchildren: 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. Available: http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-31.pdf [accessed June 2010].

Smith, C. (2008). Technology and web-based support. American Journal of Nursing, 108(9 Supplement), 64-68.

Staal, M.A. (August 2004). Stress, cognition, and human performance: A literature review and conceptual framework. (NASA Technical Memorandum 2004-212824). Moffett Field, CA: NASA-Ames Research Center.

Stoops, N. (June 2004). Educational attainment in the United States: 2003. Population characteristics. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Census Bureau. Available: http://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/p20-550.pdf [accessed June 2010].

Talley, R.C., and Crews, J.E. (2007). Framing the public health of caregiving. American Journal of Public Health, 97(2), 224-228.

Teri, L., Logsdon, R.G., Uomoto, J., and McCurry, S.M. (1997). Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: A controlled clinical trial. Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 52(4), P159-P166.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2008). The national survey of children with special health care needs: Chartbook 2005-2006. (Health Resources and Services Administration and Maternal and Child Health Bureau.) Washington, DC: Author. Available: http://mchb.hrsa.gov/cshcn05/ [accessed June 2010].

Visser, M., Goodpaster, B.H., Kritchevsky, S.B., Newman, A.B., Nevitt, M., Rubin, S.M., Simonsick, E.M., and Harris, T.B. (2005). Muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle fat infiltration as predictors of incident mobility limitations in well-functioning older persons. Journal of Gerontology, Series A, 60(3), 324-333.

Vitaliano, P.P., Echeverria, D., Yi, J., Phillips, P.E., Young, H., and Siegler, I.C. (2005). Psychophysiological mediators of caregiver stress and differential cognitive decline. Psychology and Aging, 20(3), 402-411.

Vitaliano, P., Zhang, J., and Scanlan, J.M. (2003). Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health?: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(6), 946-972.

Wilkins, V.M., Bruce, M.L., and Sirey, J.A. (2009). Caregiving tasks and training interest of family caregivers of medically ill homebound older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 21(3), 528-542.

Wingfield, A., Tun, P.A., and McCoy, S.L. (2005). Hearing loss in older adulthood: What it is and how it interacts with cognitive performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 144-148.