2

History of Nutrition Labeling

Up to the late 1960s, there was little information on food labels to identify the nutrient content of the food. From 1941 to 1966, when information on the calorie or sodium content was included on some food labels, those foods were considered by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to be for “special dietary uses,” that is, intended to meet particular dietary needs caused by physical, pathological, or other conditions.1,2,3 At that time meals were generally prepared at home from basic ingredients and there was little demand for nutritional information (Kessler, 1989). However, as increasing numbers of processed foods came into the marketplace, consumers requested information that would help them understand the products they purchased (WHC, 1970). In response to this dilemma, a recommendation of the 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health was that FDA consider developing a system for identifying the nutritional qualities of food:

Every manufacturer should be encouraged to provide truthful nutritional information about his products to enable consumers to follow recommended dietary regimens. (WHC, 1970)

This chapter provides a history of the milestones in nutrition labeling since 1969. These events are also detailed in the annex to this chapter.

VOLUNTARY NUTRITION LABELING

In response to the White House Conference, FDA developed a working draft of various approaches to nutrition labeling and asked for comment by nutritionists, consumer groups, and the food industry. Then in 1972 the agency proposed regulations that specified a format to provide nutrition information on packaged food labels. Inclusion of such information was to be voluntary, except when nutrition claims were made on the label, in labeling, or in advertising, or when nutrients were added to the food. In those cases, nutrition labeling would be mandatory.4 This action was based on Section 201(n) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (FD&C Act)5 that stated

that a food was misbranded if it “fails to reveal facts material in the light of such representation.” FDA argued that when a manufacturer added a nutrient to a food or made claims about its nutrient content, nutrition labeling was necessary to present all of the material facts, both positive and negative, about that food (Hutt, 1995).

When finalized in 1973, these regulations specified that when nutrition labeling was present on labels of FDA-regulated foods, it was to include the number of calories; the grams of protein, carbohydrate, and fat; and the percent of the U.S. Recommended Daily Allowance (U.S. RDA) of protein, vitamins A and C, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, calcium, and iron.6 Sodium, saturated fatty acids, and polyunsaturated fatty acids could also be included at the manufacturer’s discretion. All were to be reported on the basis of an average or usual serving size. The U.S. RDAs were based on the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) set forth by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in 1968 (NRC, 1968). Because of the need for a single set of standard nutrient requirements for nutrition labeling purposes, the values selected for the U.S. RDA were generally the highest value for each nutrient given in the RDA table for adult males and non-pregnant, non-lactating females. However, values for calcium and phosphorus were limited to 1 g because of their physical bulk and solubility. The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) provided for nutrition labeling of meat and poultry products in a similar manner through policy memoranda.7

As can be seen in the annex to this chapter, few changes were made in nutrition labeling regulations over the next decade (Hutt, 1995; Scarbrough, 1995). FDA, USDA, and the Federal Trade Commission held hearings in 1978 to gather information on food labeling issues and suggestions on how to make improvements.8 The vast majority of comments from the hearing favored mandatory nutrition labeling but also suggested making changes to the format to make it more useful.9

The Rise in Use of Undefined Nutrient Content and Health Claims on Labels

After 1973, scientific knowledge about the relationship between diet and health grew rapidly, and, as a result, consumers wanted to have more information on food labels, particularly on the labels of processed and packaged foods. Food manufacturers were eager to respond to the consumer interest and did so in a variety of ways, often through the use of an assortment of new, undefined claims on product labels that attempted to state or imply something about the special value of the food, such as “extremely low in saturated fat,” in order to catch consumers’ attention (Taylor and Wilkening, 2008a). The proliferation of ambiguous claims on labels and in advertising led to charges that the government was tolerating claims that were “at best confusing and at worst deceptive economically and potentially harmful” (IOM, 1990).

In addition to making claims about the nutritional content of foods, some food manufacturers were also interested in making label claims about the health benefits of their food products. FDA’s regulations had prohibited the explicit discussion of disease or health on food labels since passage of the FD&C Act in 1938.10 The implementing regulations for that act stated that a food was deemed to be misbranded if its labeling “represents, suggests, or implies: That the food because of the presence or absence of certain dietary properties is adequate or effective in the prevention, cure, mitigation, or treatment of any disease or symptom.”11 A food making such claims was considered to be misbranded or an illegal drug (Shank, 1989). This policy began when many of the links between diet and disease had yet to be established or substantiated. It helped prevent misleading and potentially harmful claims, but it also prevented useful and truthful claims from being made (Kessler, 1989). The agency’s policy was challenged in 1984 when the Kellogg Company, in cooperation with the National Cancer Institute, began a labeling campaign using the back panel of a high-fiber breakfast cereal to link fiber consumption to a possible reduction in the risk of certain cancers. That campaign changed food labeling and marketing dramatically, as other companies, in the absence of regulatory action, began making similar claims (Geiger, 1998).

The Initiation of Rulemaking for Nutritional Claims

In August 1987, FDA published a proposed rule to change its policy by permitting health claims on food labeling if certain criteria were met.12 The proposal generated a large number of thoughtful and often conflicting comments and was followed by a series of meetings between the agency and the food industry, consumer groups, academia, and health professionals (Shank, 1989). A congressional hearing was also held in December 1987. Subsequently, in February 1990, FDA withdrew its original proposal and published a new proposal that defined appropriate health claims more narrowly and set new criteria to be met before allowing a claim.13 During this time FDA also was acting to increase the availability of nutrition information and to provide for more truthful nutritional claims on all foods. In an effort to respond to consumers and the food industry, FDA initiated rulemaking to provide more flexibility in making claims on foods that could be useful in reducing or maintaining body weight or calorie intake,14 to establish policies concerning the fortification of foods,15 to include sodium content in nutrition labeling and provide for claims about sodium16 and cholesterol content,17 and to allow for food labeling experiments, such as experiments on supermarket shelf labeling.18

The surge in consumer interest in nutrition that was fueling the food industry’s desire to highlight the positive nutritional attributes of food products was due, in part, to the publication in the late 1980s of two landmark consensus reports on nutrition and health.19 The Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health (HHS, 1988) and the National Research Council’s (NRC’s) report Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease Risk (NRC, 1989a) emphasized the relationship between diet and the leading causes of death among Americans (e.g., heart disease, cancers, strokes, and diabetes). They suggested that changes in current dietary patterns—in particular, reduced consumption of fat, saturated fatty acids, cholesterol, and sodium and increased amounts of complex carbohydrates and fiber—could lead to a reduced incidence of many chronic diseases. The Surgeon General’s report also called on the food industry to reform products to reduce total fat and to carry nutrition labels on all foods. These reports made useful suggestions for planning healthy diets. However, without specific nutrition information on food labels, consumers were unable to determine how certain individual foods fit into dietary regimens that followed the recommendations of these reports. Major changes in nutrition labeling were necessary if food labels were to be useful to consumers interested in adhering to these recommendations.

INITIATIVES TO STANDARDIZE AND REQUIRE NUTRITION LABELING

In the summer of 1989, concerned that food labeling did not allow Americans to take advantage of the latest advances in nutrition, Dr. Louis W. Sullivan, then Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), directed FDA to undertake a comprehensive initiative to revise the food label (FDA, 1990).20 He later stated that, “As consumers shop for healthier food, they encounter confusion and frustration… . The grocery store has become a Tower of Babel and consumers need to be linguists, scientists and mind readers to understand the many labels they see” (HHS, 1990). This new food labeling initiative began with the publication of an advance notice of proposed rulemaking in August 1989 asking for public comment21 and a notice of public hearings to be held across the country to address the content and format of the nutrition label, ingredient labeling, and both nutrient content and health claims.22 Unlike the situation surrounding the follow-up to the 1978 public hearings when few regulatory changes were made, in 1989 a number of forces, such as advances in science, recommendations for dietary

change, food industry use of the label, and the entry of state governments into the food labeling arena, coalesced to propel important changes in the regulatory framework for food labeling (Scarbrough, 1995).

Developing Reference Values

By July 1990, FDA had published proposed rules for the mandatory nutrition labeling of almost all packaged foods.23 FDA acknowledged that there was some question as to whether the agency had the legal authority under the FD&C Act to mandate nutrition labeling on all foods that were meaningful sources of calories or nutrients, so comments were requested on that issue as well as on the proposed nutrient requirements. Simultaneously, proposals were also published to replace the U.S. RDAs24 and to establish regulations for determining serving sizes to be used in nutrition labeling.25 In replacing the U.S. RDAs, FDA sought to base new values for vitamins and minerals, to be known as Reference Daily Intakes (RDIs), on the most recent RDAs (NRC, 1989b). In addition, FDA proposed to establish new values to be known as Daily Reference Values (DRVs) for food components considered important for good health (fat, saturated fatty acids, unsaturated fatty acids, cholesterol, carbohydrate, fiber, sodium, and potassium) for which RDAs had not been established by the NAS (also see page 71). While it was necessary to establish two separate categories of nutrients (RDIs and DRVs) for regulatory purposes, FDA proposed to group the nutrients into a single set of reference values known as “Daily Values” for use in presenting nutrition information on the food label.

Establishing Required Nutrients for Food Labels

In determining which nutrients and food components to require on the label, FDA looked to The Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health (HHS, 1988) and the NRC’s report Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease Risk (NRC, 1989a). FDA proposed that calories and nutrients would be required to be listed on nutrition labels if (1) they were of public health significance as defined in these two documents, and (2) specific quantitative recommendations were set by NAS or other scientific organizations. Accordingly, FDA proposed the mandatory listing of calories, fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium, carbohydrate, fiber, protein, vitamins A and C, calcium, and iron. Additional nutrients were required to be listed when added to a food or when claims were made about them.

FDA considered the addition of total sugars to the list of required food components to declare on the label; but total sugars did not meet the criterion of having specific quantitative recommendations for intake by a scientific organization. Accordingly, the inclusion of total sugars on the nutrition label was made voluntary unless a claim was made about the sugars content of the food. Some of the comments received suggested that nutrition labeling of added sugars content also be required, but FDA did not propose to do so. The agency based its decision on (1) the fact that there was no scientific evidence that the body makes any physiological distinction between added and naturally occurring sugars; (2) a concern that the declaration of added sugars only would under-represent the sugars content of foods high in naturally occurring sugars, thus misleading consumers who may need to be aware of total sugars; and (3) an expectation that with mandatory nutrition labeling, consumers could differentiate between sugar-containing foods with high versus low nutrient content and could therefore determine which foods had the highest nutrient density.26

Moving Toward a Mandatory and Uniform Nutrition Labeling Policy

At the same time that FDA was developing its July 1990 proposal, a committee was formed at the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the health arm of NAS, to consider how food labels could be improved to help consumers adopt or adhere to healthy diets. FDA and FSIS/USDA sponsored the study based on the belief that changes in

eating habits could improve the health of Americans and that food labeling could aid consumers in making wise dietary choices. The committee’s report, Nutrition Labeling: Issues and Directions for the 1990s, was issued in September 1990 (IOM, 1990). It recommended that FDA and FSIS adopt regulations to institute mandatory and uniform nutrition labeling for almost all packaged foods, and it made recommendations concerning various facets of nutrition labeling, including the content and presentation of information, in order to support findings and recommendations of The Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health (HHS, 1988) and the NRC’s report Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease Risk (NRC, 1989a). It also recommended that FDA and USDA should define descriptors (e.g., “high,” “good source of”) for the content of nutrients such as fat, cholesterol, sodium, and micronutrients.

PASSAGE OF THE NUTRITION LABELING AND EDUCATION ACT (NLEA) OF 1990

Congressional concerns about food labeling had been building for some time. Members of Congress were aware of consumer and industry interest in the subject and had responded by asking the General Accounting Office to investigate labeling issues and by introducing a variety of bills on the subject (Scarbrough, 1995). This culminated in November 1990 with passage of the NLEA,27 the most significant food labeling legislation in 50 years. The NLEA amended the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act28 to give FDA explicit authority to require nutrition labeling on most food packages and specified the nutrients to be listed in the nutrition label. It also required that nutrients be presented in the context of the daily diet; specified that serving sizes should represent “an amount customarily consumed and which is expressed in a common household measure that is appropriate to the food”; and provided for a voluntary nutrition labeling program for raw fruits, vegetables, and fish. It also required standard definitions to be developed that characterized the level of nutrients and required that FDA provide for approved health claims. The NLEA’s requirements for the content of the nutrition label were very similar to those in FDA’s 1990 proposal except that the NLEA included complex carbohydrates and sugars in the list of required nutrients. It also permitted the agency to add or delete nutrients based on a determination that such a change would “assist consumers in maintaining healthy dietary practices.” On November 27, 1991, FDA proposed 26 new food label regulations to implement the NLEA. These included a new proposal on nutrition labeling and the establishment of RDIs and DRVs29 and a proposal on serving sizes.30 General principles for nutrient content claims and the definition of terms for claims to be allowed were also proposed,31 as were general principles for health claims,32 followed by individual proposals pertaining to ten possible topic areas for health claims, such as dietary fiber and cancer, which were identified in the NLEA. While the format of the nutrition label was discussed in its November 27, 1991, proposal, FDA published a more detailed proposal for the format on July 20, 1992.33 The purpose of FDA’s proposals was threefold: to clear up confusion that had surrounded nutrition labeling for years, to help consumers choose healthier diets, and to give food companies an incentive to improve the nutritional qualities of their products (Kessler, 1995).

The NLEA pertains only to those labels of food products regulated by FDA, which has label authority over the majority of foods. However, meat and poultry product labels are under the authority of FSIS in the USDA, and alcoholic beverage product labels are under the authority of the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau of the Department of the Treasury, formerly the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. Leadership at USDA strongly supported the claim that consumers need help to adopt and adhere to healthy diets. For this reason and to provide consistent regulation for all foods, the decision was made to have FSIS coordinate efforts with FDA to implement the requirements of NLEA for meat and poultry product labels (McCutcheon, 1995). To accomplish this, FSIS first published an advance notice of proposed rulemaking to solicit comments to assist in developing regulations

for the nutrition labeling of meat and poultry products.34 Then, on November 27, 1991, in conjunction with FDA, FSIS published proposed rules to establish a voluntary nutrition labeling program for single-ingredient raw meat and poultry (consistent with NLEA’s provision for raw fruits, vegetables, and fish) and mandatory nutrition labeling for all other meat and poultry products.35 It also proposed the adoption of most of FDA’s proposals in regard to nutrient content claims and proposed additional definitions for “lean” and “extra lean” as unique descriptors for meat and poultry products.

The NLEA established very tight timeframes for implementing the provisions of the act. It required FDA to publish proposed regulations within 12 months and final regulations within 24 months of enactment of the act.36 If the agency failed to publish final regulations as specified, the proposed rules were to become final rules. With those time constraints and over 40,000 written comments on the proposed rules to respond to, FDA and FSIS mobilized their staffs to accomplish the task.

Declaration of Nutrient Content

Final regulations for both agencies were published on January 6, 1993, that mandated nutrition labeling in the form of a Nutrition Facts panel on most packaged foods.37 Exemptions were allowed for foods that were insignificant sources of calories or nutrients, foods shipped in bulk for further processing, restaurant foods, foods manufactured by some small businesses, medical foods, and infant formula (the latter having other specific rules for labeling). Nutrients to be listed on nutrition labels included calories, calories from fat, total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium, total carbohydrate, dietary fiber, sugars, protein, vitamins A and C, calcium, and iron. By way of exception when present at insignificant amounts and when no claims were made about them, regulations allowed the declaration of calories from fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, dietary fiber, sugars, vitamins A and C, calcium or iron to be omitted if a footnote was added at the bottom of the list of nutrients stating “Not a significant source of ____” with the blank filled in by the name of the nutrients(s) omitted. If they chose to do so, manufacturers were permitted to list calories from saturated fat, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, potassium, soluble and insoluble fiber, sugar alcohols, other carbohydrates, and any vitamins and minerals for which RDIs were established; labeling became required, however, if vitamins and minerals were added to the product or if claims related to vitamin or mineral content were made. In order to reduce consumer confusion and avoid the potential for misleading labels, no other nutrients were allowed in the Nutrition Facts panel.

Despite being specified in the NLEA, complex carbohydrates were not included in the allowed list of nutrients. Comments had convinced FDA that there was no consensus on a definition for the term “complex carbohydrates” as it related to physiological effects, health benefits, or dietary guidance. Instead, the rules allowed for the voluntary listing of “other carbohydrates” to be calculated as that amount of carbohydrate remaining after subtraction of the amount of dietary fiber, sugars, and sugar alcohols from total carbohydrate.

Just as with the FDA proposals in 1990, the declaration of sugars also generated discussion in comments to the 1991 proposals to implement the NLEA. Based on comments received, the proposed definition of sugars as the sum of all free mono- and oligosaccharides through four saccharide units was changed to the sum of all free mono- and disaccharides. Other comments had recommended that added sugars should be listed rather than total sugars since there was both a dietary recommendation to use sugars in moderation and a dietary recommendation for increased consumption of fruits, which are sources of naturally occurring sugars (HHS/USDA, 1990). Opposing comments reiterated concerns expressed in the proposed rule that the body makes no physiological distinction between the two types of sugars and that under-representing total sugars content could be misleading to consumers concerned about total intake of sugars. The determinative issue, however, was that there were no analytical methods for distinguishing between the two types of sugars. Product labels are checked for accuracy and compliance by FDA through laboratory analysis of the food product as packaged. That analysis yields only a

value for total sugars. FDA policy is that it should not promulgate regulations that it cannot enforce. Accordingly, the decision was made to list only total sugars in the Nutrition Facts panel.

Several comments on the 1991 proposed rule suggested that trans fatty acids (trans fat) should be included in the nutrition label, either with saturated fat or as a separate category. FDA disagreed at the time because reports were inconsistent regarding the effects of trans unsaturated fats on blood cholesterol levels in humans (LSRO/FASEB, 1985; Grundy and Denke, 1990). However, soon afterwards, new data emerged indicating that trans fats raise LDL-cholesterol concentrations nearly as much as cholesterol-raising saturated fats (NIH, 1994). Based on its own independent evaluation of studies on the effects of trans fat on blood cholesterol levels, FDA concluded that under conditions of use in the United States, trans fats did contribute to increased serum LDL cholesterol, which increases the risk of coronary heart disease. As a result, a proposed rule was published in 1999 to modify the Nutrition Facts panel to include trans fats on food products regulated by FDA.38 In 2003, FDA issued a final rule requiring trans fats to be listed on a separate line immediately under saturated fat whenever present in amounts of 0.5 g or more per serving, except that it must always be listed if claims are made on the label about it.39 USDA regulations permit, but do not require, trans fat to be listed on nutrition labels of meat and poultry products provided the declaration and definitions of trans fat adhere to the FDA regulations.40

Determination of Reference Values

As discussed above, for declaring amounts of vitamins and minerals, FDA had proposed replacing U.S. RDAs with RDIs based on the most current scientific knowledge as incorporated in the 1989 RDAs from the NAS (NRC, 1989b). It also proposed to use a population-adjusted mean of the RDA values for the various age–sex groups for each nutrient rather than the highest value for each nutrient.41 However, on October 6, 1992, Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Act of 1992 that, in section 203, instructed FDA not to promulgate for at least one year any regulations that required the use of, or were based upon, RDAs other than those in effect at that time.42 Inasmuch as the NLEA required that final rules be promulgated by November 6, 1992, FDA was unable to wait long enough to utilize the 1989 RDAs. Instead, FDA proceeded to change the name of the U.S. RDAs to RDIs to reduce confusion with the RDAs developed by the NAS while maintaining the values based on the NAS 1968 RDAs.43 Once the moratorium on using newer RDA values was over, FDA decided to wait until revisions then in progress at the NAS were finalized. It did, however, proceed to establish RDIs for those nutrients for which RDA values had not been established in 1968: vitamin K, selenium, manganese, chromium, molybdenum, and chloride.44 The agency also asked the NAS to convene a committee to provide scientific guidance about how to use the new Dietary Reference Intakes from the NAS to update the nutrient reference values used in the Nutrition Facts panel. The committee’s report became available in 2003 (IOM, 2003). Then, in 2007, FDA issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking asking for comment on which reference values the agency should use to calculate the percent of daily value in the Nutrition Facts panel and whether certain nutrients should be added or removed from the labels.45

Establishment of Daily Reference Values

A challenge presented by the NLEA was the requirement that the nutritional information “be conveyed to the public in a manner which enables the public to readily observe and comprehend such information and to understand its relative significance in the context of a total daily diet.”46 This requirement necessitated reporting

|

38 |

64 FR 62746. |

|

39 |

68 FR 41434. |

|

40 |

A Guide to Federal Food Labeling Requirements for Meat and Poultry Products, Available online: http://www.fsis.usda.gov/pdf/labeling_requirements_guide.pdf (accessed September 19, 2010). |

|

41 |

55 FR 29476 and 56 FR 60366. |

|

42 |

Dietary Supplement Act of 1992, Public Law 102-571. |

|

43 |

58 FR 2206. |

|

44 |

60 FR 67164. |

|

45 |

72 FR 62149. |

|

46 |

Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990. Public Law 101-535, 104 Stat 2353, Sec. 2(b)(1)(A). |

in relation to a daily reference value the amounts of all nutrients listed and not just the amounts of vitamins and minerals, as had been done since voluntary nutrition labeling rules were put in place in 1973. In accordance with its 1990 proposal, the final nutrition labeling rules established for the first time reference values, known as Daily Reference Values (DRVs), that would be used in reporting values of total fat, saturated fatty acids, cholesterol, total carbohydrate, dietary fiber, sodium, and potassium—for which RDAs had not been established in 1989—and for protein.47 The DRVs were based largely on recommendations from The Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health (HHS, 1988), the NRC’s report Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease Risk (NRC, 1989a), and the National Cholesterol Education Program’s “Report of the Expert Panel on Population Strategies for Blood Cholesterol Reduction” (NIH, 1990). The recommendations used for total fat were 30 percent of calories or less; for saturated fat, less than 10 percent of calories; for cholesterol, less than 300 mg; for total carbohydrate, 60 percent of calories; for sodium, 2,400 mg; for potassium, 3,500 mg; and for protein, 10 percent of calories (so that calorie-providing nutrients sum to 100 percent of calories). The DRV for fiber, for which the two consensus documents had not provided a recommendation, was instead based on a recommendation in a report of the Life Sciences Research Organization of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology that fiber intake be 10 to 13 g per 1,000 calories (LRSO, 1987). No recommendations existed for intake of sugars, so no DRV was established. For those nutrients for which the recommendation was for a percent of calories, the DRVs were based on a caloric intake of 2,000 calories. For example, the level for total fat was derived by calculating 30 percent of 2,000 calories and dividing by 9, which is the number of calories per gram of fat. The resulting value, 66.7 g, was then rounded down to 65 g for ease of use. In an effort to show consumers how the values would differ with different caloric intakes, the regulations called for a footnote on larger food packages that would state, “Your daily values may be higher or lower depending on your calorie needs,” followed by a table showing the daily values for both a 2,000- and 2,500-calorie diet.

Basic Format of Nutrition Label

The format to be used for the nutrition label had been a topic of the 1989 advance notice of proposed rule-making48 and the public hearings49 on nutrition labeling. Many speakers at the public hearings supported a new label format in order to simplify the label and make it more understandable (FDA, 1990). Prior to the 1991 proposals, focus group sessions had been held (Lewis and Yetley, 1992) and experimental studies conducted (Levy et al., 1991, 1996) to determine the effectiveness of various label formats. The results were made available to the public, and comments were requested.50 FDA also initiated a cooperative pilot program with industry to test alternative formats which led to several industry-sponsored studies,51 and it held a public meeting on the subject.52 The research showed that graphic presentations, such as pie charts and bar graphs, were not well suited for conveying the diversity and amount of information required on nutrition labels, so FDA looked to a format based more on consumers’ ability to use and comprehend numeric values (Scarbrough, 1995). The format proposed in July 1992 was one that included quantitative amounts of macronutrients but that gave particular emphasis to a column of nutrient values expressed as a percent of the label reference value, the RDIs and DRVs, which was to allow consumers to quickly determine if the food contained a little or a lot of a nutrient.53 At the end of the comment period, when a format had been determined that provided the proper context and emphasis, FDA worked with graphic experts to design the label, taking into account research on comprehension, legibility, and literacy (Kessler et al., 2003).

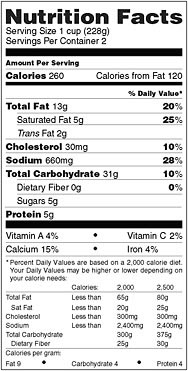

The format research and comments on the proposed rule had led FDA to conclude that in nutrition labeling a consistent system of percentages makes it possible for virtually all the nutrients on the label to be provided in equivalent units—as a percent of the appropriate RDI or DRV (to be known on the Nutrition Facts panel simply as

FIGURE 2-1 Nutrition Facts panel.

SOURCE: 21 CFR 101.9(d)(12).

the “Percent of Daily Value”).54 That consistency is not possible when the list contains nutrients given in different units (e.g., grams and milligrams). Thus, a low value on the list is likely to be a “true” low value within the context of the daily diet, and a high value is likely to be a “true” high value. This consistency also allowed educational programs to be built around the concept that 5 percent or less of any nutrient is a small amount, whereas 20 percent or more is a large amount (Taylor and Wilkening, 2008a). Consumers had often been confused by earlier nutrition label formats when comparing nutrient amounts, such as comparing fat in grams with sodium in milligrams, so the actual quantities were moved adjacent to the name of the nutrient where they would get less attention. To put emphasis on the amount of nutrients in a serving of food “in the context of a total daily diet,” the format for the Nutrition Facts panel provided for a separate column for the listing of Percent of Daily Value (% Daily Value or %DV) (see Figure 2-1). Noticeably, a few nutrients are lacking a value in the %DV column. For trans fat and sugars, scientific evidence was not sufficient to support the establishment of a RDI or DRV. In the case of protein, a DRV had been established, but the %DV for protein required taking into account protein quality and not just the quantity of protein present. Such a calculation requires the computation of the protein-digestibility-corrected amino acid score for a food, a costly analysis. Because the typical American diet provides enough protein of sufficiently high biological quality to meet the nutritional needs of most persons, protein intake is not a public health concern. Therefore, listing the %DV for protein is voluntary for foods intended for adults and children 4 or more years of age unless a protein claim is made for the product.

Determination of Serving Size

The serving size of a food product affects virtually every number in the Nutrition Facts panel other than those in the footnote. As a result, the development of regulations prescribing the manner in which it is to be calculated for the wide diversity of foods available in the market was of major importance. The NLEA required that serving sizes be based on amounts customarily consumed55 rather than on recommended portion sizes, as some comments had suggested, or on a 100-g basis, as is done in some other countries. To determine the amount customarily consumed, FDA utilized food consumption data from USDA’s nationwide food consumption and intake surveys, augmented by other sources of information where available.56 In order to facilitate consumer comparisons, categories of foods that are generally used interchangeably in the diet and that have similar product characteristics were developed so that those foods would have uniform serving sizes. Statistical analyses of consumption data, using the mean, median, and modal values, were then utilized to develop Reference Amounts Customarily Consumed (RACC) for each category.57 Procedures for converting the RACC values to serving sizes expressed in common household measures were specified in the regulations.58

Single-Serving Containers

Single-serving-size containers proved to be particularly troublesome (Taylor and Wilkening, 2008a). The regulations require that most packages that are less than 200 percent of the applicable RACC must declare the entire package as one serving. If the package is 200 percent or more of the RACC and the whole unit can reasonably be consumed at one time, the manufacturer may, but need not, declare the package as one serving. For products that are more than 200 percent of the RACC yet intended to be consumed by one individual at one time, FDA has encouraged manufacturers to base the nutrition information on the entire contents of food in the container (CFSAN/FDA, 2004; FDA, 2004). Because there is little evidence that this is widely practiced (Taylor and Wilkening, 2008a), FDA asked in a 2005 advance notice of proposed rulemaking for comment on whether its regulations should be changed to require packages that can reasonably be consumed at one eating occasion to provide the nutrition information for the entire package, either alone or in conjunction with a listing of the serving size derived from the RACC.59 Also, because there is evidence that Americans are eating larger portion sizes than in the 1970s and 1980s, when the food consumption surveys upon which RACCS are based were conducted (Nielsen and Popkin, 2003; Smiciklas-Wright et al., 2003), comments were requested on which RACCs may need to be updated.

Serving Size and Health Outcomes

The increase in portion sizes consumed is considered to be one of many factors leading to increased obesity in the United States (Young and Nestle, 2002). To address the issue of obesity, Mark McClellan, then FDA Commissioner, created a committee in 2003 to outline an action plan to cover critical dimensions of the obesity problem from FDA’s perspective and within its regulatory authorities. Among other topics, the committee’s report, entitled Calories Count: Report of the Working Group on Obesity (FDA, 2004), addressed food labeling issues pertaining to serving sizes and the design of the Nutrition Facts panel. The advance notice of proposed rulemaking mentioned above was an outcome of that report, as was another advance notice asking for comment on ways to increase the prominence of calorie information on the label.60 At the time of this report, action on those issues is still awaited.

Specification of Nutrient Content Claims

In addition to requiring food labels to contain information on the amounts of certain nutrients, the NLEA also specified that claims characterizing the level of a nutrient may be made on food labels only if the characterization uses terms that have been defined in regulations.61 The NLEA further specified that claims characterizing the relationship of any nutrient to a disease or health-related condition be made only in accordance with regulations promulgated under the act; however, such claims, known as “health claims,” are not the subject of this report and will not be discussed further here. The intent of this section of the NLEA was to allow meaningful comparisons of foods and to encourage the consumption of foods with the potential to improve dietary intake and reduce chronic disease (Taylor and Wilkening, 2008b).

Defining Descriptive Nutrient Content Claims

The act specifically required that definitions for the terms “free,” “low,” “light,” “reduced,” “less,” and “high” in relation to nutrients required to be listed in the Nutrition Facts panel.62 In addition, to allow for the use of claims that were being used on labels of conventional foods in the marketplace, FDA and USDA also defined the terms “good source,” “more,” “fewer,” “lean,” and “extra lean”63 when implementing the NLEA and provided for the use of synonyms for many of the terms. Subsequently, both agencies also defined the implied claim “healthy.”64 The current definitions for all these claims on FDA-regulated food items can be found in Appendix B of this report. A full discussion of the rationale behind the definition of each claim can be found in the preambles to the proposed (1991) and final (1993) rules (see Annex). It should be noted that the definitions for claims on individual food products differ in some respects from those for meal and main dish items. Meal and main dish items are combinations of foods intended to contribute a larger portion of the total daily diet, which necessitates separate criteria, often based on an amount per 100 g, in order to provide for appropriate claims.65

Briefly, in developing the criteria for claims, FDA took into account the dietary recommendations for each nutrient; the amounts of the nutrient present per RACC, per serving size, and per 100 g; the distribution and abundance of the nutrient in the food supply; analytical methods; and the presence of other nutrients that could possibly cause a particular claim to be misleading.

Defining Levels of Nutrients to Limit

In the case of “free” claims, levels of each nutrient were selected that were at or near the reliable limit of detection for the nutrient in food and that were considered to be dietetically trivial or physiologically inconsequential.66 In the case of foods that are inherently free of a nutrient, regulations require that the claim must refer to all foods of that type rather than to a particular brand to which the labeling is attached (e.g., “broccoli, a fat-free food”).67

Claims for “low” levels of nutrients presented a bigger challenge and needed to be considered individually. The goal was “that the selection of a food bearing the term should assist consumers in assembling a prudent daily diet and in meeting overall dietary recommendations to limit the intake of certain nutrients.”68 For nutrients that are ubiquitous in the food supply, the definition of a “low” level was set at 2 percent of the DRV for the nutrient. If the nutrient was not ubiquitous, the amount defined to be “low” was adjusted to account for the nutrient’s uneven distribution in the food supply. In that way, if a person was to consume a reasonable number of servings of food labeled as “low,” balanced with a number of servings of foods that do not contain the nutrient and a number of servings of foods that contain the nutrient at levels above the “low” level, he or she would still be able to stay

within dietary recommendations. For example, the DRV for total fat was set at 65 g. Two percent of 65 g is 1.3 g, which was rounded up to 1.5 g. Since fat is not inherent in many foods (e.g., fruits, vegetables, non-dairy beverages, fat-free dairy products, jams, etc.), yet is found in more than a few foods, FDA concluded that an appropriate upper limit for a “low fat” claim should be set at two times 2 percent of the DRV, or 3 g. Balancing the number of foods that do not contain fat with those that contain more than “low” levels would allow a person consuming up to 20 foods a day to stay within the DRV of 65 g. An exception to this method of calculation was made for sodium inasmuch as the term “low sodium” had been defined 8 years earlier as 140 mg or less per serving (rather than 96 mg if following the new procedure) with no apparent concerns about that level. Also, unique to sodium, there was a regulatory definition for “very low sodium” at 35 mg or less per serving. Responding to comments, FDA maintained these definitions for use by individuals wishing to reduce total sodium intake and those on medically restricted diets.69

Defining Levels of Nutrients to Encourage

Claims for “positive” nutrients (e.g., vitamins and minerals) are used to emphasize the presence of a nutrient. Regulations provide for claims at two levels, “high” and “good source.”70 The definition for “high” was set at 20 percent or more of the appropriate RDI or DRV per serving. The IOM committee had suggested a criterion of greater than 20 percent for “high” claims (IOM, 1990), and in a review of its food consumption database FDA found that the 20 percent cut would permit a sufficient number of foods to make the claim. This in turn would enable consumers using the claim to select a diet from a wide variety of foods rather than from a few highly fortified foods.71 “Good source” claims, defined as 10 to 19 percent of the DRV, were intended to emphasize the presence of a nutrient at a mid-range of nutrient content, drawing consumers’ attention to foods that contain a significant amount of a nutrient and that are likely to help meet dietary recommendations.72

Implied Claims

As opposed to claims about the specific amount of a nutrient present in a food, “implied claims” are claims that describe a food or an ingredient in such a manner that the consumer is led to assume that a nutrient is absent or present in a certain amount (e.g., “high in wheat bran” implies that the food is high in fiber).73 Implied claims can also suggest that the food may be useful in maintaining healthy dietary practices. To that end, following publication of the final rules implementing NLEA, FDA and USDA issued proposed74 and final rules75 to define the implied claim implicit in “healthy.” The term “healthy” was considered a unique nutrient content claim because it not only characterized the level of the nutrients in a food but also implied a judgment about the food. Comments on the proposed rule suggested that consumers had varying ideas of what the term meant, leading FDA to find that the “fundamental purpose of a ‘healthy’ claim is to highlight those foods that, based on their nutrient levels, are particularly useful in constructing a diet that conforms to current dietary guidelines.”76 This led the FDA and USDA to set criteria that limited use of the term to foods that had “low” levels of fat and saturated fat and slightly more moderate levels of cholesterol and sodium (see Appendix B). In addition, the food (other than raw fruits or vegetables, a single ingredient or a mixture of canned or frozen fruits or vegetables or enriched cereal grain products that conform to a standard identity) had to contain at least 10 percent of the RDI or DRV of vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, iron, protein, or fiber. As for sodium, FDA was persuaded that levels of it should be restricted so that foods bearing the “healthy” claim would be helpful in reaching dietary goals. Yet the agency found that

the majority of products bearing the claim would be disqualified from doing so if sodium levels were set at a level as low as 360 mg per serving. Therefore, to provide time for the industry to reformulate their products and for consumers to become accustomed to lower levels of sodium, final regulations issued on May 10, 1994, provided a two-tier approach to sodium levels, specifying a maximum level for individual foods at 480 mg per serving, with a requirement that the level drop to 360 mg per serving by January 1, 1998. Prior to the 1998 date, FDA and USDA received petitions from a food manufacturer asking that the more restrictive second tier be eliminated or at least delayed until there were advances in food technology that allowed for the development of acceptable products with reduced sodium content. The agencies found that issues raised relative to technological and safety concerns of reduced-sodium foods merited further consideration, so it extended the effective date.77 This process continued until final rules were issued which abandoned the more restrictive sodium requirements altogether because of the documented technical difficulties in finding suitable alternatives for sodium that would be acceptable to consumers.78

NUTRITION LABELING AS AN EVOLVING PROCESS

Nutrition labeling is a tool for consumers to use in selecting healthy diets that meet dietary recommendations. To accomplish this, it must be flexible enough to accommodate continuing advances in science and nutrition as well as changes in consumer behavior. The need for these changes is evidenced by the current advance notices of proposed rulemaking pertaining to modifications to give more prominence to calories,79 amendments to serving-size regulations,80 and the establishment of new reference values.81 Current activities regarding front-of-package labeling are another example of innovative approaches to nutrition labeling designed to help consumers select foods that may lead to more healthful diets.

REFERENCES

CFSAN/FDA (Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition/Food and Drug Administration). 2004. Letter to food manufacturers about accurate serving size declaration on food products. College Park, MD: FDA.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). 1990. Food labeling reform. Washington, DC: FDA. Pp. 1–23.

FDA. 2004. Calories count: Report of the working group on obesity. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration.

Geiger, C. 1998. Health claims: History, current regulatory status, and consumer research. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 98:1312–1322.

Grundy, S., and M. Denke. 1990. Dietary influences on serum lipids and lipoproteins. Journal of Lipid Research 31:1149–1172.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 1988. The Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health. DHHS Publication No. 88–50210. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

HHS. 1990. Remarks by Louis W. Sullivan, M.D., Secretary of Health and Human Services at the National Food Policy Conference (pp. 1–12). Washington, DC: HHS.

HHS/USDA (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/U.S. Department of Agriculture). 1990. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Hutt, P. 1995. A brief history of FDA regulation relating to the nutrient content of food. In Nutrition labeling handbook, edited by R. Shapiro, New York City: Marcel Dekker. Pp. 1–27.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1990. Nutrition labeling, issues and directions for the 1990s. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003. Dietary Reference Intakes: Guiding principles for nutrition labeling and fortification. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kessler, D. A. 1989. The federal regulation of food labeling, promoting foods to prevent disease. New England Journal of Medicine 321:717–725.

Kessler, D. A. 1995. The evolution of national nutrition policy. In Annual Review of Nutrition, Vol. 15, edited by D. B. McCormick. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews.

Kessler, D. A., J. R. Mande, F. E. Scarbrough, R. Schapiro, and K. Feiden. 2003. Developing the “Nutrition Facts” food label. Harvard Health Policy Review 4:13–24.

Levy, A., S. Fein, and R. Schucker. 1991. Nutrition labeling formats: Performance and preference. Food Technology 45:116–121.

Levy, A., S. Fein, S., and R. Schucker. 1996. Performance characteristics of seven nutrition label formats. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 15:1–15.

Lewis, C., and E. Yetley. 1992. Focus group sessions on formats of nutrition labels. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 92:62–66.

LSRO (Life Sciences Research Office). 1987. Physiological effects and health consequences of dietary fiber. Bethesda, MD: Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology.

LSRO/FASEB (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology). 1985. Health effects of dietary trans fatty acids. Bethesda, MD: FASEB.

McCutcheon, J. 1995. Nutrition labeling of meat and poultry products—An overview of regulations from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In Nutrition labeling handbook, edited by R. Shapiro. New York: Marcel Dekker. Pp. 53-63.

Nielsen, S., and B. Popkin. 2003. Patterms and trends in food portion sizes, 1977–1998. Journal of the American Medical Association 289:450–453.

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 1990. National Cholesterol Education Program: Report of the expert panel on population strategies for blood cholesterol reduction. Wasington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

NIH. 1994. Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults National Cholesterol Education Program: Second report of the expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel II). Circulation 89:1329–1445.

NRC (National Research Council). 1968. Recommended Dietary Allowances. Washington, DC: National Research Council.

NRC. 1989a. Diet and health: Implications for reducing chronic disease risk. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC. 1989b. Recommended Dietary Allowances. 10th edition. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Scarbrough, F. 1995. Perspectives on Nutrition Labeling and Education Act. In Nutrition labeling handbook, edited by R. Shapiro. New York: Marcel Dekker. Pp. 29–52.

Shank, F. A. 1989. Health claims on food labels: The direction in which we’re headed. Journal of the Association of Food & Drug Officials 53:45–49.

Smiciklas-Wright, H., D. Mitchell, S. Mickle, and J. Goldman. 2003. Foods commonly eaten in the United States, 1989–1991 and 1994–1996: Are portion sizes changing? Journal of the American Dietetic Association 103:41–47.

Taylor, C., and V. Wilkening. 2008a. How the nutrition food label was developed, Part 1: The nutrition facts panel. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 108:437–442.

Taylor, C., and V. Wilkening. 2008b. How the nutrition food label was developed, Part 2: The purpose and promise of nutrition claims. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 108:618–623.

WHC (White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health). 1970. White House conference on food, nutrition, and health: Final report. 1970. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Young, L. R., and M. Nestle. 2002. The contribution of expanding portion sizes to the US obesity epidemic. American Journal of Public Health 92:246-249.

ANNEX MILESTONES IN NUTRITION LABELING

TABLE 2-1 Milestones in Nutrition Labeling

|

Date |

Activity |

References |

Nutrition Labeling |

Claims |

|

1941 |

Proposed rule to prescribe label statements for dietary properties of foods represented as being for special dietary use and to establish minimum daily requirement values for vitamins and minerals |

6 FR 3304-3310; 21 CFR Part 125 |

|

X |

|

1941 |

Final rule prescribing label statements for dietary properties of foods represented as being for special dietary use and establishing minimum daily requirements for vitamins and minerals |

6 FR 5921-5926; 21 CFR Part 125 |

|

X |

|

1962 |

Proposed rules for food for special dietary uses that would define terms for label statements relating to vitamins and minerals, for use in weight control (e.g., “low calorie”), and for use in regulating the intake of sodium |

27 FR 58155818; 21 CFR Part 125 |

|

X |

|

1966 |

Final rules for food for special dietary uses that defined terms for label statements relating to vitamins, minerals, and protein; for use in weight control (e.g., “low calorie”); and for use in regulating the intake of sodium |

31 FR 8521-8524; 21 CFR Part 125 |

|

X |

|

1969 |

White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health recommends that FDA consider the development of a system for identifying the nutritional qualities of food |

|

|

|

|

1971 |

Proposed rule on labeling of foods with information on cholesterol, fat, and fatty acid composition |

36 FR 11521-11522; 21 CFR Part 125.12 |

X |

|

|

1972 |

Proposed rules for voluntary nutrition labeling of packaged foods (except mandatory when nutrient claims are made or nutrients added) and for Recommended Daily Allowances to be used as a reference standard for nutrition labeling |

37 FR 6493-6497; 21 CFR Part 1.16 |

X |

|

|

1972 |

Final rule on label statements for foods intended to regulate the intake of sodium |

37 FR 9763-9764; 21 CFR Part 125.9 |

|

X |

|

1973 |

Final rule establishing rules for voluntary nutrition labeling of packaged foods (except mandatory when nutrient claims are made or nutrients added) and U.S. Recommended Daily Allowances (U.S. RDAs) to be used as a reference standard |

38 FR 2125-2132; 21 CFR Part 1.17 |

X |

|

|

1973 |

Final rule on labeling of foods with information on cholesterol, fat, and fatty acid composition (separate from nutrition label) |

36 FR 2132-2137; 21 CFR Part 1.18 |

X |

|

|

1973 |

Amendments to final rules on nutrition labeling and labeling of information on cholesterol, fat, and fatty acid composition |

38 FR 6950-6964; 21 CFR Parts 1.17and 1.18 |

X |

|

|

1977 |

Tentative order on label statements for special dietary foods for use in reducing or maintaining weight or calorie intake (e.g., “low calorie”) |

42 FR 37166-37176; 21 CFR Parts 105.66 and 105.67 |

|

X |

|

1978 |

Announcement of five public hearings to discuss food labeling, including nutrition labeling and claims |

43 FR 25296-25307 |

X |

X |

|

1978 |

Final rule on label statements for special dietary foods for use in reducing or maintaining weight or calorie intake (e.g., “low calorie”) |

43 FR 43248-43262; 21 CFR Parts 105.66 and 105.67 |

|

X |

|

1978 |

Proposed rule to permit “reduced calorie” claim for bread with 25% reduction in calories |

43 FR 43261-43262; 21 CFR Part 105.66 |

|

X |

|

1979 |

Tentative positions of FDA, USDA, and FTC on food labeling issues as a result of public hearings |

44 FR 75990-76020 |

X |

X |

|

1980 |

Final policy statement on the addition of nutrients to food (i.e., fortification) |

45 FR 6314-6324; 21 CFR Part 104.20 |

|

|

|

Date |

Activity |

References |

Nutrition Labeling |

Claims |

|

1982 |

Proposed rule to establish definitions for sodium claims (e.g., “sodium free,” “reduced sodium,” “no salt added”) and safety review |

47 FR 26580-26595; 21 CFR Part 105.69 |

|

X |

|

1983 |

Temporary exemption from food labeling rules for conducting authorized food labeling experiments aimed at providing consumers with more useful food labeling information (e.g., shelf labeling) |

48 FR 15236-15241; 21 CFR Part 101.108 |

X |

|

|

1984 |

Final rule establishing definitions for sodium claims and requiring inclusion of sodium in nutrition labeling information whenever nutrition labeling appears on food labels |

49 FR 15510-15535; 21 CFR Parts 101.9, 101.13, and 105.69 |

X |

X |

|

1986 |

Proposed rule to establish definitions for cholesterol claims (e.g., “cholesterol free”) and amend nutrition labeling rules to require that the declaration of either fatty acid or cholesterol content information will require that both be provided in nutrition labeling |

51 FR 42584-42593; 21 CFR Parts 101.9, and 101.25 |

X |

X |

|

1987 |

Proposed rule to exclude nondigestible dietary fiber when determining the calorie content of a food for nutrition labeling purposes |

52 FR 28690-28691; 21 CFR Part 101.9 |

X |

|

|

1987 |

Proposed rule to codify and clarify the agency’s policy on the appropriate use of health messages on food labeling |

52 FR 28843-28849; 21 CFR Part 101.9 |

|

X |

|

1989 |

Advance notice of proposed rulemaking to announce a major initiative of HHS to improve food labeling with request for public comment on labeling requirements, including nutrition labeling and claims |

54 FR 32610-32615 |

X |

X |

|

1989 |

Announcement of four public hearings to discuss food labeling issues, including nutrition labeling and claims |

54 FR 38806-38807 |

X |

X |

|

1990 |

Reproposed rule to provide for the use of health messages on food labeling and to withdraw the August 4, 1987, proposal |

55 FR 5176-5192; 21 CFR Part 101.9 |

X |

X |

|

1990 |

Tentative final rule establishing definitions for cholesterol claims and requiring that declaration of either fatty acid or cholesterol content information triggers declaration of both in nutrition labeling |

55 FR 29456-29473; 21 CFR Parts 101.9 and 101.25 |

X |

X |

|

1990 |

Proposed rule to replace U.S. RDAs with Reference Daily Intakes (RDIs) for protein and 26 vitamins and minerals and to establish Daily Reference Values (DRVs) for fat, saturated fatty acids, unsaturated fatty acids, cholesterol, carbohydrate, fiber, sodium, and potassium |

55 FR 29476-29486; 21 CFR Parts |

101.3, 101.9, and 104.20 |

X |

|

1990 |

Proposed rule to require nutrition labeling on most packaged foods and to revise the list of required nutrients and conditions as well as the format for listing nutrients in nutrition labeling |

55 FR 29487-29517; 21 CFR Part101.9 |

X |

|

|

1990 |

Proposed rule to define serving size on the basis on the amount of food commonly consumed per eating occasion and to establish standard serving sizes for 159 food product categories to assure uniform serving sizes upon which consumers can make nutrition comparisons among food products |

55 FR 2951729533; 21 CFR Parts 101.8, 101.9, and 101.12 |

X |

|

|

1990 |

Passage of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 (NLEA) mandating nutrition labeling on most packaged foods and providing for nutrient content claims and health claims on food labels |

Public Law 101-585 (Sec. 403(q)and (r) of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act) |

X |

X |

|

1991 |

Proposed rule with notice of FDA’s plans to respond to passage of NLEA |

56 FR 1151-1152 |

X |

X |

|

1991 |

Notice of public meeting to discuss issues related to how serving size should be determined and presented as a part of nutrition labeling |

56 FR 8084-8092 |

X |

|

|

1991 |

Advance notice of proposed rulemaking to solicit comment on nutrition labeling of meat and poultry products (USDA) |

56 FR 13564-13573 |

X |

|

|

1991 |

Notice of a vailability of a report on food label formats conducted by FDA and request for comment on nutrition label format research |

56 FR 23072-23083 |

X |

|

|

1991 |

In response to requirements of the NLEA proposed rule to modify proposal of July 19, 1990, on mandatory nutrition labeling and the establishment of RDIs and DRVs for use in nutrition labeling |

56 FR 60366-60394; 21 CFR Parts 101.9 and 101.36 |

X |

|

|

1991 |

In response to requirements of the NLEA and comments received, proposed rule to modify proposal of July 19, 1990, on serving sizes for use in nutrition labeling |

56 FR 60394-60421; 21 CFR Parts 101.9 and 101.12 |

X |

|

|

1991 |

Proposed rule to define nutrient content claims for calories, sugar, and sodium and for claims such as “source,” “high,” “more,” and “light,” and to provide for their use on food labels |

56 FR 60421-60478; 21 CFR Parts 101.13, 101.54, 101.60, 101.61, 101.69, 101.95, and 105.66 |

|

X |

|

1991 |

Proposed rule to define nutrient content claims for fat, fatty acids, and cholesterol and to provide for their use on food labels |

56 FR 60478- 60512; 21 CFR Parts 101.25 and 101.62 |

|

X |

|

1991 |

Proposed rule to establish general requirements for health claims that characterize the relationship of a food component to a disease or health-related condition on the labels and in labeling of foods |

56 FR 60537-60566; 21 CFR Parts 101.14, 101.70, and 101.71 |

|

X |

|

1991 |

Proposed rule to permit voluntary nutrition labeling of single-ingredient meat and poultry products, to establish mandatory nutrition labeling of all other meat and poultry products, and to establish nutrient content claims for use on meat and poultry product labels (USDA) |

56 FR 60302-60364; 9 CFR Parts 317, 320, and 381 |

X |

X |

|

1992 |

Proposed rule on format for presenting nutrition information on food labels |

57 FR 32058-32089 |

X |

|

|

1992 |

Passage of the Dietary Supplement Act of 1992, which put a 1-year moratorium on regulations that required the use of, or were based upon, RDAs other than those in effect at that time |

Public Law 102-571 |

X |

|

|

1993 |

Final rule requiring nutrition labeling on most packaged foods and specifying a new format for declaring nutrition information |

58 FR 2079-2205; 21 CFR Part 101.9 |

X |

|

|

1993 |

Final rule establishing Reference Daily Intakes and Daily Reference Values, to be known as Daily Values, for declaring the nutrient content of a food |

58 FR 2206-2228; 21 CFR Part 101.9 |

X |

|

|

1993 |

Final rule defining serving sizes based on amounts customarily consumed per eating occasion, provide for their use, and establish reference amounts for 139 food categories |

58 FR 2229-2300; 21 CFR Parts 101.8, 101.9, and 101.12 |

X |

|

|

1993 |

Final rule establishing general principles for the use of nutrient content claims, define terms such as “free,” “low,” “lean,” ”high,” “reduced,” “light,” “less,” and “fresh,” and provide for the use of implied nutrient content claims |

58 FR 2302-2426; 21 CFR Parts 101.13, 101.54-101.69, and 101.95 |

|

X |

|

1993 |

Final rule to establish general principles for the use of health claims |

58 FR 2478-2536; 21 CFR Part 101.14 |

|

X |

|

1993 |

Proposed rule to define the implied nutrient content claim “healthy” |

58 FR 2944-2949, 21 CFR Part 101.65 |

|

X |

|

1993 |

Proposed rule to permit the term “healthy” on meat and poultry products (USDA) |

58 FR 688-691; 9 CFR Parts 317.363 and 381.463 |

|

X |

|

1993 |

Final rule to permit voluntary nutrition labeling on single-ingredient raw meat and poultry products, to establish mandatory nutrition labeling for all other meat and poultry products, and to establish nutrient content claims for use on meat and poultry product labels (USDA) |

58 FR 632-685; 9 CFR Parts 317, 320, and 381 |

X |

X |

|

1994 |

Proposed rule to establish Reference Daily Intakes for vitamin K, selenium, manganese, fluoride, chromium, molybdenum, and chloride for use in nutrition labeling |

59 FR 427-432; 21 CFR Part 101.9 |

X |

|

|

1994 |

Final rule defining the term “healthy” for use on meat and poultry product labeling (USDA) |

59 FR 24220-24229; 9 CFR Parts 317.363 and 381.463 |

|

X |

|

1994 |

Final rule defining the term “healthy” for use on the food label |

59 FR 24232-24250; 21 CFR Part 101.65 |

|

X |

|

1995 |

Proposed rule to amend general principles for the use of nutrient content and health claims to provide additional flexibility and encourage their use in order to assist consumers in maintaining a healthy diet |

60 FR 66206-66227; 21 CFR Parts 101.13 and 101.14 |

|

X |

|

Date |

Activity |

References |

Nutrition Labeling |

Claims |

|

1995 |

Final rule to provide codified language for nutrition labeling regulations that were previously cross-referenced to FDA regulations (USDA) |

60 FR 174-216; 9 CFR Parts 317 and 381 |

X |

|

|

1995 |

Final rule establishing Reference Daily Intakes for vitamin K, selenium, manganese, chromium, molybdenum, and chloride |

60 FR 67164-67175; 21 CFR Part 101.9 |

X |

|

|

1998 |

Notice of a vailability of a guidance document on notifications for nutrient content or health claims based on an authoritative statement of a scientific body in response of FDA Modernization Act of 1997 |

63 FR 32102 |

|

X |

|

1999 |

Proposed rule to require the addition of trans fatty acids to nutrition labeling and to define a nutrient content claim for the “free” level of trans fatty acids |

64 FR 62746-62825; 21 CFR Parts 101.9, 101.13, and 101.14 |

X |

|

|

1999 |

Notice of availability of guidance on significant scientific agreement in the review of health claims for conventional foods and dietary supplements |

64 FR 17494 |

|

X |

|

2003 |

Proposed rule to amend regulations that pertain to sodium levels in foods that use the term “healthy” on product labels |

68 FR 8163-8179; 21 CFR Part 101.65 |

|

X |

|

2003 |

Final rule requiring the addition of trans fatty acids to nutrition labeling |

68 FR 41434-41506; 21 CFR Part 101.9 |

X |

|

|

2005 |

Advance notice of proposed rulemaking to request comment on amending nutrition labeling regulations to give more prominence to calories of food labels |

70 FR 17008-17010 |

X |

|

|

2005 |

Advance notice of proposed rulemaking to request comment on amending nutrition labeling regulations concerning serving size |

70 FR 17010-17014 |

X |

|

|

2005 |

Final rule amending regulations that pertain to sodium levels in foods that use the term “healthy” on product labels |

70 FR 56828-56849; 21 CFR Part 101.65 |

|

X |

|

2006 |

Interim final rule concerning level of sodium in labels of meat and poultry products that bear the term “healthy” (USDA) |

71 FR 1683-1686; 9 CFR Parts 317.363 and 381.463 |

|

X |

|

2006 |

Guidance for industry on FDA’s implementation of “qualified health claims” http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/GuidanceDocuments/FoodLabelingNutrition/ucm053843.htm |

May 2006 |

|

X |

|

2007 |

Advance notice of proposed rulemaking to request comments on establishing new reference values (i.e., RDIs and DRVS) |

72 FR 62149-62175 |

X |

|

|

2009 |

Guidance for industry on evidence-based review for the scientific evaluation of health claims http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/GuidanceDocuments/FoodLabelingNutrition/ucm073332.htm |

January 2009 |

|

X |

|

NOTE: Table excludes foods for special dietary use (other than label statements about nutrient content), dietary supplements, foods for infants less than 1 year of age, individual health claims, and the voluntary nutrition labeling program for raw fruits, vegetables, and fish. Unless otherwise noted, regulations and notices have been issued by the Food and Drug Administration of the Department of Health and Human Services. |

||||