9

Implementation

The effectiveness of the recommended Meal Requirements for the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) will be determined in large part by two major factors: (1) the manner in which the new requirements are implemented and monitored for compliance and (2) the extent to which the children and adults who are enrolled for care in participating child or adult care facilities consume appropriate amounts of the foods that are offered. Clients’ consumption of the food served (the second factor) will be strongly influenced by the implementation methods that are used (the first factor). The first section of this chapter focuses on ways to promote the implementation of key elements of the recommended Meal Requirements. The second section addresses technical assistance pertaining to engaging stakeholders, menu planning, controlling costs, and meeting reporting requirements. The third section addresses the need for revisions to reporting requirements and monitoring procedures. The fourth section presents specific recommendations to support the implementation of the recommended Meal Requirements. The fifth section considers options for updating the Meal Requirements in response to future changes in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (HHS/USDA, 2005) and the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs).

Food service operations vary widely across CACFP settings. As used in this chapter, the term food service operation refers to preparation facilities that range from home kitchens in day care homes, to small “mom and pop”-type facilities, to large institutional kitchens. In a large majority of the CACFP settings, the facilities, personnel, and other resources are much more limited than those in school meals programs.

PROMOTING THE IMPLEMENTATION OF KEY ELEMENTS OF THE RECOMMENDED MEAL REQUIREMENTS

Overview

Implementation of the key elements of the recommended Meal Requirements for CACFP (see section “Recommended Meal Requirements” in Chapter 7) will require many changes on the part of providers, sponsoring organizations, state agencies, and organizations that develop educational materials and offer training for CACFP providers. The committee recognizes that changes in Meal Requirements to meet Dietary Guidelines increase the complexity and cost of being a CACFP provider and introduce foods that may be unfamiliar to many clients. Two major concerns are that implementation of the new Meal Requirements may negatively affect participation by (1) care providers and (2) clients. Especially in the current economy, any loss of revenue based on decreased participation by clients or increased costs to providers would present a real threat to the financial stability of the program. Providers may themselves be economically challenged while serving mainly low-income younger children or low-income disabled and older adults. Reduced participation in CACFP by care providers would weaken the food safety net and could have negative effects on the nutrition of those needing care.

Therefore, careful consideration needs to be given to the many aspects of implementing change. A plan that introduces change incrementally over a realistic time frame—one developed with the involvement of key stakeholders—may be an important step in the successful implementation of the new Meal Requirements.

Measures to Increase the Feasibility of Implementing Key Elements of the Meal Requirements

This section covers (1) implementing key elements for infants, (2) measures to address key elements for those ages 1 year and older, and (3) measures that are more general in scope. A sample of the many resources that may be tapped to assist with implementation efforts is presented in Appendix M.

Implementing Key Elements for Infants

For infants, the key elements of the new Meal Requirements involve delaying the introduction of infant meats, cereals, vegetables, and fruits until the age of 6 months and the omission of fruit juice of any type before 1 year of age. These changes are expected to be feasible right away, in large part because they bring CACFP into alignment with the food packages and

education provided by the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Implementing Key Elements for Clients Ages 1 Year and Older

This subsection first addresses general factors that may foster clients’ acceptance of the recommended changes in foods offered. Second, it covers measures to address the availability of suitable foods in food deserts (neighborhoods and communities that have limited access to affordable and nutritious foods [IOM, 2009]). Then, it covers each of the key elements individually. Cost is addressed separately in the section “Controlling Costs.” The committee recognizes that a large proportion of providers may already have incorporated many of these measures into their care settings but anticipates that many providers may need to adopt new or improved approaches to successfully implement the key elements of the recommended Meal Requirements.

Fostering clients’ acceptance of change In general, food consumption is fostered by the appropriate timing of meals, adequate time for eating the meal, suitable style of meal service, positive interactions with adults during mealtime for younger children, pleasant eating spaces, the availability of assistance with eating and texture modifications for those with chewing or swallowing difficulties, and the scheduling of playtime for younger children or free unstructured relaxed time for the adults. To the extent that foods new to providers are to be incorporated into menus, the providers will need to become familiar with easy, tasty, and appealing ways to prepare and serve them. In addition, menu items need to be developmentally, geographically, and culturally appropriate. For children, repeated exposures to new foods over time improve their preference for those foods (Birch, 1987; Birch and Marlin, 1982). Although waste will occur when children are introduced to foods, it is developmentally appropriate to continue to offer the food. Involving child and adult participants, families or other regular care givers, and CACFP staff members in taste-testing new food items or recipes may be helpful.

Increasing the amount and variety of vegetables To provide the most practical approach to ensuring a suitable variety of vegetables over the week, strategies will need to be developed and tested. To foster acceptance of a variety of vegetables, steps can be taken to make them more appealing in appearance, taste, and texture. A number of studies have documented that repeated exposure to fruit and vegetables results in higher preference for and/or intake of those foods (Bere and Klepp, 2005; Brug et al., 2008; Cooke, 2007; Cullen et al., 2003; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2003; Wardle et

al., 2003). The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) could explore how the lessons learned from initiatives such as the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program can inform the implementation of this key element. The committee is aware of anecdotal reports of the positive impact of the exposure to fresh fruits and vegetables on children, families, and the local community (e.g., expansion into grocery stores).

Increasing the proportion of whole grain-rich foods Based on studies that have demonstrated that an incremental increase in whole wheat content of food items resulted in favorable whole grain consumption by children (Burgess-Champoux et al., 2006; Chan et al., 2008; Marquart, 2009; Rosen et al., 2008), it is reasonable to expect the acceptance of whole grain-rich foods—especially if they are introduced gradually. Additionally, products made with white whole wheat and other lighter-colored whole grains can be used in place of refined grains, as these types of flour minimize changes in product appearance and thus increase acceptance (Marquart, 2009).

Specifying fruit in place of most juice Many fruit options are available because the fruit may be unsweetened fresh, frozen, canned, or (in some cases) dried. The higher cost of fruit compared with juice may be the major deterrent.

Serving foods that are low in solid fats, trans fat, added sugars, and sodium Easy-to-use materials can be developed based on the proposed table of food specifications (Table 7-8 in Chapter 7). The two biggest challenges are expected to be the availability, in any market, of reasonably priced and palatable prepared or partially prepared foods that are low in sodium (IOM, 2010) and a suitable selection of these foods in rural or urban food deserts.

Serving acceptable lean meat or meat alternatives at breakfast A number of suitable choices are available. Examples include low-fat or fat-free yogurt, low-fat cheese, nuts or seeds (or “butters” [spreads] made from them), cooked dried beans, and lean meats (taking care to limit highly processed high-sodium meats to once per week considering all meals).

Serving snacks to meet a weekly pattern Approaches to meet this requirement will need to be developed and tested to determine the most practical methods of implementation and monitoring.

Using the enhanced snack option If the enhanced snack is provided in place of two regular snacks, it will be expected to reduce the time required for serving and clean-up.

General Measures

Regardless of the exact nature of the new Meal Requirements that are put into effect by USDA, measures that will promote their successful implementation include (1) involving the family, community, and other key stakeholders and (2) training state agency staff and providers.

Involving the family, community, and other key stakeholders The value of parental involvement in nutrition in child care is evident in the study Improving Nutrition and Physical Activity in Child Care: What Parents Recommend (Benjamin et al., 2008). In this study, parents recommended an increase in fruits and vegetables and the provision of more healthful meals. The authors concluded, “This information may be used to create or modify interventions or policies and to help motivate parents to become advocates for change in child care” (p. 1907). Partnerships with older American and child care policy makers, adult and child organization advocacy groups, and individuals in the child and adult care environment will be a key ingredient in the successful implementation of the recommendations related to changes in the meal pattern for increasing consumption of whole grains and reducing solid fats, added sugars, and sodium.

Additional ways to involve stakeholders include the following:

-

Forming broad-based advisory committees specific to the different care settings. Useful tasks include the development of implementation timelines in advance of the new requirements. These timelines can inform planning for menu revisions, training, and budgets so that all processes are in place when the new requirements are released.

-

Forming local partnerships including relevant state agencies responsible for program administration; program providers; and other key stakeholders, such as representatives from state licensing organizations. In many states, the licensing organizations require that licensed child care providers follow requirements that are similar to or more stringent than the CACFP Meal Requirements—regardless of their participation in the federal food program.

Training of state agency staff, sponsors, and program providers Adequate training for state agency staff with responsibility for administration of the programs is important to ensure the fidelity of the implementation of the new Meal Requirements. Because state agencies play a key role in delivering training and technical assistance to sponsoring institutions and program providers, state agencies will need comprehensive training. The delivery of effective training for the CACFP providers is the most essential component of successful implementation. Steps could be taken to partner with the National

Institute of Food and Agriculture Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP), which would be especially helpful in training for providers in day care homes and adult day care (see Appendix M). Further information on training appears in the section “Providing Technical Assistance.”

Providing nutrition education Culturally appropriate nutrition education can be a useful strategy for promoting behavior change and increasing the consumption of more healthful foods on the part of clients. It may also be useful in addressing parents’ or guardians’ concerns and beliefs that may be in conflict with the recommended Meal Requirements. The work of the National Food Service Management Institute (NFSMI) in cataloging the many research-based nutrition education publications can be leveraged for use in the various child and adult care program settings. See Appendix M for more information about the NFSMI and other nutrition education resources.

Phasing in Changes

By convening a panel of expert CACFP sponsors, providers, state administrators, CACFP associations (see Appendix M), and trainers, it is possible that USDA could identify a process for phasing in the essential elements with the goal of supporting the recommended Meal Requirements. Such a group could identify steps to take to gradually reach the goal of meeting the full set of recommendations. For example, instead of requiring that breakfast include lean meat or meat alternate three times per week and extra bread or other grain product on the other two days, initially the provider could be given a choice of whether to serve meat or meat alternates at all. Similarly, a method could be devised to ensure that a wide variety of vegetables would be served over the week, with limits on starchy vegetables, but without specifying the exact number of servings from each vegetable subgroup to be served.1 Simplified “rules” developed from the proposed table of food specifications (Table 7-8) might be made more stringent every year or two. This would provide a mechanism for gradually serving a greater proportion of the grain products as whole grain-rich foods and reducing the use of foods that are high in solid fats, added sugars, and sodium.

Providing Technical Assistance

To achieve effective implementation of the recommended Meal Requirements in a cost-effective manner, technical assistance will be needed. The technical support must be comprehensive and adaptable to all program settings.

|

1 |

The committee definitely does not favor reducing the amount of vegetables required per day even though that would be the most effective cost-saving measure. See the section “Controlling Costs.” |

The recommended Meal Requirements involve major shifts in the current approach to managing the food service operation. Therefore, regardless of the approach being used by a day care facility, providers will need to learn specific strategies for meeting new Meal Requirements. The approaches will need to be tailored to the type of care facility. Among the many skills and competencies needed are culturally sensitive menu planning approaches, label reading, best practices for menu compliance, food purchasing and preparation techniques, controlling costs, relationships among nutrition and health, developmentally appropriate feeding practices, and keeping food safe to eat.

Training could include the use of step-by-step instructional materials—print, video, or web-based—and guided hands-on experiences. Many resources are available that USDA could tap to assist with developing training materials and/or provide the training. Some of these are listed in Appendix M. The following subsections highlight four types of technical assistance that will be needed as a result of changes in the Meal Requirements: (1) engaging stakeholders, (2) meeting menu planning challenges, (3) controlling costs, and (4) meeting reporting requirements.

Engaging Stakeholders

Because the recommended Meal Requirements call for substantial changes in meals served in CACFP care settings, there is a strong need to engage stakeholders and promote their acceptance and support of the changes. Providers, program participants, and family members are among the key stakeholders. Importantly, program providers will need support to become accepting of the new meal patterns and food specifications. Technical assistance will be needed for state agencies, sponsoring institutions, centers, and day care homes to develop the attitudes and skills needed to engage stakeholders in a way that gains their support of the changes.

Meeting Menu Planning Challenges

The recommended Meal Requirements pose new challenges that will require menu planners to approach their task with a clear understanding of the meal patterns and food specifications. Practical methods will need to be developed and tested to help providers meet a number of anticipated menu planning challenges specific to CACFP, such as the following:

-

Increasing the amount of vegetables served daily, the daily proportion of grain foods that are whole grain-rich, and the variety of vegetables served over the day and week;

-

Designing and grouping menu item choices to ensure that each child and adult receives meals that meet the minimum amounts of each food group and subgroup during the week;

-

Providing the recommended variety of food groups in the snacks served over the week;

-

Identifying food products in the local marketplace that are affordable, fit with the food specifications, and appeal to the CACFP participants;

-

Implementing incremental menu item changes (to permit providers to develop the skills and abilities to prepare and serve the new items successfully); and

-

Adapting menus to meet cultural preferences for vegetarians, and for accommodating food allergies, food intolerances, and specific dietary restrictions.

One priority is collaboration between USDA and state agencies responsible for program administration to revise related menu planning guidance materials, including the current Food Buying Guide for Child Nutrition Programs (USDA/FNS, 2008), to make its content compatible with the recommended Meal Requirements for both children and adults. To meet the meal pattern for each age group, program providers may benefit from learning to design cycle menus.2 Cycle menus offer ease and clarity in counting the number and type of required fruits, vegetables, and grains for the week (thus helping providers to comply with meal pattern requirements). Cycle menus also may aid budgeting, purchasing (shopping), the preparation and service of new menu items, and overall meal quality. The sample menus that the committee wrote to illustrate the application of the standards for menu planning (see Appendix K) provide examples of sound principles of menu planning. However, they are not expected to be suitable for any particular CACFP setting without some adaptation for ethnic, cultural, and local food preferences; food availability; and the capabilities of the food service operation. CACFP providers may want to use these menus as guides when developing and tailoring their own specific menus.

Controlling Costs

Increasing the amount and quality of food to be consistent with the recommended Meal Requirements will increase food costs, as described in Chapter 8. USDA and Congress will need to determine the extent to which they will support the recommended Meal Requirements (and thus national initiatives to increase access to more healthful meals) through regulations or adequate funding, respectively. Substantial improvements

in CACFP meals can be expected only to the extent that care providers (1) are mandated to provide more fruits and vegetables, a greater proportion of whole grain-rich grain foods, and lean meats or meat alternates rather than high-fat choices and (2) receive sufficient funding to make this possible. An unfunded mandate would be expected to result in a loss of CACFP providers. Increasingly, more state regulatory agencies are implementing policy changes to improve the healthfulness of meals served in licensed facilities. Making CACFP regulations and funding more congruent with these policies and with national initiatives to improve diet and health will foster better care for the vulnerable populations that require care.

The committee was asked to be sensitive to cost but not to make funding recommendations. The committee worked to address the needs of the target populations and align its recommendations for Meal Requirements with updated dietary guidance and nutritional science as directed by the committee’s statement of task (see “The Committee’s Task,” Chapter 1). Although reducing the amount of vegetables in the recommended Meal Requirements would lower the cost substantially, doing so would be contrary to the Dietary Guidelines, which put a strong emphasis on consuming more vegetables to promote health, and also contrary to the first key element of Meal Requirement Recommendation 2.

At current federal reimbursement levels, providers will be challenged to meet the anticipated increase in food costs and increases in non-food meal costs described in Chapter 8. In addition, CACFP sponsors and administering state agencies will have substantially increased labor costs related to training, technical assistance, and monitoring. According to a USDA report, “costs reported by sponsors on average were about 5 percent higher than allowable reimbursement amounts” (USDA/ERS, 2006, p. 1). Technical assistance and training will be needed to help providers meet the Meal Requirements while controlling the expected increases in costs, but increases in food costs will be unavoidable. Unlike school operations, CACFP care facilities do not generate program revenue from á la carte or catering sales and thus have no mechanism to generate income other than increasing the cost of care to the client—a serious limitation in view of the high proportion of low-income clients.

Guidance would be helpful for the small “mom and pop” child and adult care facilities, including day care homes that serve low-income families primarily and that rely on local small grocery stores—especially to providers who are new to CACFP. Such stores generally have higher food prices (Powell et al., 2007). Lessons could be learned from the experienced providers who have made arrangements to procure food through supermarkets, big box stores, or food buying clubs to help reduce food costs—including the strategies they use to store food safely.

Meeting Reporting Requirements

The changes in the Meal Requirements will call for a revision of the reporting requirements, as indicated below. Otherwise, one of the unintended consequences could be an increase in disallowed meals and snacks (that is, a loss of income resulting from the denial of claims for reimbursement for meals served because the various requirements appear not to have been met). Technical assistance will be needed to enable child and adult care directors and/or key food service personnel to meet those reporting requirements efficiently and accurately. Providers must be given timely information on the various federal, state, and local policies and regulations (e.g., record keeping including meal counting; how to document appropriately using food purchasing receipts; menus; and other records)—along with clear instructions on how to meet them.

Well-designed and well-executed technical assistance could add value even to the best-run child and adult care centers and home operations by enhancing providers’ nutrition knowledge, menu planning, food preparation, and business record-keeping skills.

Revising Reporting Requirements and Monitoring Procedures for CACFP Meals

Reporting Requirements

As described in Chapter 2, many CACFP providers have difficulty meeting reporting requirements—that is, providing the data needed to document that the meals they serve are eligible for reimbursement. The recommended Meal Requirements would make it even more challenging to meet the current reporting requirements without the needed training, technical assistance, and revisions to the reporting requirements described above.

Monitoring Procedures

One aspect of the current monitoring of CACFP meals focuses on the meal components with the objective of making certain that reimbursement is warranted for the meals that were served. The overall objective of a revised approach to this aspect of the monitoring of CACFP meals could be to ensure their nutritional quality and consistency with the Dietary Guidelines. USDA could consider both a short-term approach to monitoring during the initial stage of implementation of the new Meal Requirements and a revised approach during the second stage, once implementation is well under way. Because unintended consequences may arise as a result of extensive changes in the Meal Requirements, another suggested key focus of monitoring is

the identification of problems that may need to be addressed by the state agency or USDA—and also of any unexpected benefits that would provide evidence of the need for continued support of the program.

During the first stage, at least for the next several years, monitoring could be directed toward facilitating the transition to the new Meal Requirements. The initial approach might address a few elements at a time but occur on a frequent basis. The emphasis might be on examining progress in meeting the Meal Requirements (especially those related to fruits, vegetables, whole grain-rich foods, and the food specifications), identifying training needs for CACFP sponsors and providers, and providing needed technical assistance to improve the CACFP meals.

The subsequent approach to monitoring (the second stage) could continue to focus on gathering and using information to enhance the ability of providers to plan, prepare, and serve meals that are consistent with the new Meal Requirements. This second stage of monitoring could focus on documenting that planned menus and prepared meals are consistent with the recommended meal pattern (the first step in ensuring that meals that are counted or claimed for reimbursement are consistent with program requirements).

During both stages of monitoring, a variety of methods could be used to monitor how well the CACFP facilities have implemented the new Meal Requirements. For example, monitors could focus on whether CACFP facilities are offering only low-fat and fat-free milks, at least half of the grains as whole grain-rich products, and the required numbers and types of fruits and vegetables. This level of review could include menu review.

All this information could be used to (1) establish a baseline for CACFP food operations, (2) identify technical assistance needs, (3) prepare a plan, in cooperation with CACFP providers, for addressing these needs, and (4) monitor progress over time. In addition to focusing on planned menus and prepared meals, the assessment would address CACFP providers’ access to vegetables, fruits, and whole grains and participants’ acceptance of them.

RECOMMENDATIONS TO SUPPORT THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE REVISED MEAL REQUIREMENTS

In order to bring the Meal Requirements into alignment with the best available guidance, consistent with the nutritional requirements of other programs of the Food and Nutrition Service, the committee makes the following implementation recommendations:

Implementation Strategy Recommendation 1: USDA, working together with state agencies, and health and professional organizations should provide extensive technical assistance to implement the recommended

Meal Requirements. Key aspects of new technical assistance to providers include measures to continuously improve menu planning (including variety in vegetable servings and snack offerings across the week), purchasing, food preparation, and record keeping (see the section “Providing Technical Assistance” for more detail). Such assistance will be essential to enable providers to meet the Meal Requirements while controlling cost and maintaining quality.

Implementation Strategy Recommendation 2: USDA should work strategically with the CACFP administering state agencies, CACFP associations, and other stakeholders to reevaluate and streamline the systems for monitoring and reimbursing CACFP meals and snacks. The CACFP National Professional Association and the Child and Adult Care Food Program Sponsor’s Association would be key partners. Several aspects of the existing monitoring and reimbursement processes will need to be revised to enable states to efficiently administer the CACFP program with the new recommended Meal Requirements in place. The procedures would be expected to (1) focus on meeting relevant Dietary Guidelines and (2) provide information for continuous quality improvement and for mentoring program operators to assist in performance improvement. Among the challenges will be the development of practical methods for states to monitor for the meeting of weekly requirements and for minimizing providers’ reporting requirements.

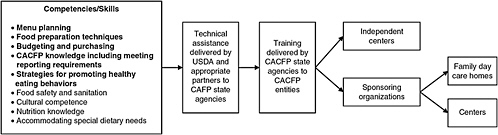

To prepare for successful implementation of the new requirements, USDA must provide for comprehensive training and technical support to the state administering agencies either directly or in cooperation with partners. Those agencies, in turn, need to ensure that the providers can receive the appropriate types of technical support. Figure 9-1 depicts the paths by which technical assistance related to various competencies and skills reaches providers. Note that state agencies and sponsoring institutions both have roles in improving the competencies and skills of providers. State administrators, local sponsors, and providers could collaborate and network with local education agencies, universities, and state early child care providers to develop training materials or participate in training.

Policies and systems are already in place in a number of parts of the country that could assist USDA in gradually rolling out the Meal Requirements in a manner that would support state agencies, sponsoring organizations, and providers. Because of the diverse program settings and providers, USDA is strongly encouraged to develop or make available effective tools that will assist CACFP providers to successfully implement the new Meal Requirements. Such tools include lists of allowable and unallowable food items, web-based training and menu-planning tools, portion-size charts and

FIGURE 9-1 Paths for developing the competencies and skills of Child and Adult Care Food Program providers needed to implement recommended Meal Requirements.

NOTE: Current CACFP regulations require that state agencies as well as participating entities provide annual training to institutions and key staff. The competencies (in bold) are important areas for focus in order to achieve successful implementation are provided to program participants. of the revised Meal Requirements. However, competency is essential in all areas noted to ensure that healthy and safe meals and snacks

calculators, step-by-step calculators/charts to determine whole grain-rich food items, and lists of subgroups of vegetables. These tools must be sensitive to different cultures as well as geographic locations, and appropriate tools must be available for providers with language barriers or limited education.

The committee recognizes the NFSMI, EFNEP, and the USDA Agricultural Library (see Appendix M) as valuable starting places for information for all levels of key child and adult care personnel, but particularly for the directors and the food preparers. They provide excellent resources for networking, mentoring and training, and learning opportunities. Nonetheless, new resources will be needed to help providers meet the recommended Meal Requirements.

SUMMARY

Successful implementation of the recommended Meal Requirements will require attention to key elements of achieving change. The focus must be on providing extensive comprehensive technical assistance that is adapted for CACFP providers at all levels and on reevaluating and streamlining the systems for monitoring and reimbursing meals.

REFERENCES

Benjamin, S. E., J. Haines, S. C. Ball, and D. S. Ward. 2008. Improving nutrition and physical activity in child care: What parents recommend. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 108(11):1907–1911.

Bere, E., and K. I. Klepp. 2005. Changes in accessibility and preferences predict children’s future fruit and vegetable intake. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2:15.

Birch, L. L. 1987. The role of experience in children’s food acceptance patterns. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 87(9 Suppl):S36–S40.

Birch, L. L., and D. W. Marlin. 1982. I don’t like it; I never tried it: Effects of exposure on two-year-old children’s food preferences. Appetite 3(4):353–360.

Brug, J., N. I. Tak, S. J. te Velde, E. Bere, and I. de Bourdeaudhuij. 2008. Taste preferences, liking and other factors related to fruit and vegetable intakes among schoolchildren: Results from observational studies. British Journal of Nutrition 99(Suppl 1):S7–S14.

Burgess-Champoux, T., L. Marquart, Z. Vickers, and M. Reicks. 2006. Perceptions of children, parents, and teachers regarding whole-grain foods, and implications for a school-based intervention. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 38(4):230–237.

Chan, H. W., T. Burgess-Champoux, M. Reicks, Z. Vickers, and L. Marquart. 2008. White whole-wheat flour can be partially substituted for refined-wheat flour in pizza crust in school meals without affecting consumption. Journal of Child Nutrition and Management 32(1). http://docs.schoolnutrition.org/newsroom/jcnm/08spring/en.asp (accessed October 6, 2010).

Cooke, L. 2007. The importance of exposure for healthy eating in childhood: A review. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 20(4):294–301.

Cullen, K. W., T. Baranowski, E. Owens, T. Marsh, L. Rittenberry, and C. De Moor. 2003. Availability, accessibility, and preferences for fruit, 100% fruit juice, and vegetables influence children’s dietary behavior. Health Education and Behavior 30(5):615–626.

HHS/USDA (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2005. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 6th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. http://www.health.gov/DietaryGuidelines/dga2005/document/ (accessed July 23, 2008).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. The Public Health Effects of Food Deserts. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2010. Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Marquart, L. 2009. Incorporating Whole Grain Foods into School Meals and Snacks. Presented at the Institute of Medicine, Committee on Nutrition Standards for National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs Open Forum, Washington, DC, January 28, 2009.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., M. Wall, C. Perry, and M. Story. 2003. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents: Findings from Project EAT. Preventive Medicine 37(3):198–208.

Powell, L. M., S. Slater, D. Mirtcheva, Y. Bao, and F. J. Chaloupka. 2007. Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. Preventive Medicine 44(3):189–195.

Rosen, R. A., L. Sadeghi, N. Schroeder, M. Reicks, and L. Marquart. 2008. Gradual incorporation of whole wheat flour into bread products for elementary school children improves whole grain intake. Journal of Child Nutrition and Management 32(1). http://www.schoolnutrition.org/Content.aspx?id=10584 (accessed October 6, 2010).

USDA/ERS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Economic Research Service). 2006. Administrative Costs in the Child and Adult Care Food Program: Reimbursement System for Sponsors of Family Child Care Homes. http://ddr.nal.usda.gov/bitstream/10113/32789/1/CAT31012231.pdf (accessed October 12, 2010).

USDA/FNS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service). 2008. Food Buying Guide for Child Nutrition Programs. Alexandria, VA: USDA/FNS. http://teamnutrition.usda.gov/Resources/foodbuyingguide.html (accessed November 2, 2010).

Wardle, J., M. L. Herrera, L. Cooke, and E. L. Gibson. 2003. Modifying children’s food preferences: The effects of exposure and reward on acceptance of an unfamiliar vegetable. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57(2):341–348.