2

The Child and Adult Care Food Program

The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) has the broadest scope of any of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) food programs that specifically target vulnerable populations. In particular, it subsidizes nutritious meals and snacks served to infants and children in participating day care facilities, emergency shelters, and at-risk afterschool programs, and to adults who receive day care in participating facilities. Moreover, a majority of the participants (and many of the providers) are from low-income households. This chapter covers a variety of topics important to the development of revised Meal Requirements. After providing an overview of CACFP, this chapter highlights key elements of the history and growth of the program, describes program settings and clientele, summarizes important aspects of the program’s administration and regulations, addresses the program’s role in providing a food and nutrition safety net for vulnerable populations, and ends with a brief summary.

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

The goal of CACFP is to serve nutritious meals and snacks to participating children and adults. Ordinarily, the program serves children no older than 12 years of age. However, there are two exceptions: it may serve (1) migrant children ages 15 years and under and (2) youths up to 18 years of age in afterschool programs and in shelters. Adults in participating day care facilities generally are ages 60 years and older. However, individuals from 18 up to 60 years of age may participate if they require daily supervision because of functional limitations.

TABLE 2-1 General Aspects of Current CACFP Meal Requirements

|

Eating Occasion |

Current Requirements |

|

All |

Must meet daily pattern, which may differ by age group and setting. The pattern specifies the number of meal components (shown below) and the amount of each. |

|

Breakfast |

3 meal components |

|

Lunch or supper |

4 meal components |

|

Snacks |

Any 2 of 4 components |

|

Meal Component |

|

|

Fruit/vegetable |

Any fruit and/or vegetable |

|

Grain |

Enriched or whole grain |

|

Meat/alternate |

None required at breakfast, no restrictions on types |

|

Milk |

No restrictions |

|

Food Component |

|

|

Energy |

No requirement |

|

Micronutrients |

No requirement |

|

Fats |

No restrictions |

|

Sodium |

No restrictions |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from USDA/FNS, 2010a. |

|

To receive reimbursement for the meals and snacks served, participating programs are required to provide meals and snacks according to requirements set by USDA. In this report, the term meal component refers to the food groups required in the meals, and the term food component refers to nutrients and other substances contained in food. General aspects of the current CACFP Meal Requirements are shown in Table 2-1.

PROGRAM SETTINGS

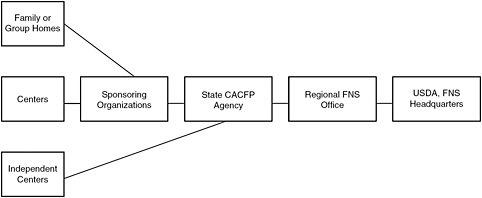

CACFP is administered in three major types of day care settings, whether for children or adults: family or group homes, centers, and independent centers. The entity responsible for administering the local program depends on the type of setting, as shown in Figure 2-1. Independent centers report directly to the state CACFP agency, whereas other centers and family or group homes must operate under the auspices of a sponsoring organization. A community action agency is a common example of a sponsoring organization. For further information, see the section “Administration and Regulations, Overview.”

Sponsoring organizations and independent centers (see Figure 2-1) enter into agreements with their state administering agency to assume administrative and financial responsibility for CACFP operations at the local level, and each state CACFP agency administers the program within the

FIGURE 2-1 CACFP settings as administered through USDA FNS.

NOTES: CACFP = Child and Adult Care Food Program; FNS = Food and Nutrition Service; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture. All day care homes and centers must come into the program under a sponsoring organization, which provides training, technical assistance, and monitoring. State CACFP agencies approve sponsoring organizations and independent centers, monitor the program, provide guidance, and administer CACFP in most states. USDA FNS administers CACFP at the federal level through grants to states.

SOURCE: Adapted from USDA/FNS, 2000.

state. Public or private entities that are eligible to participate in CACFP are described below (USDA/FNS, 2010b).

Day Care Centers for Children and Adults

Child Day Care

Public or private nonprofit child care centers, outside school hours care centers, Head Start programs, and other institutions that are licensed or approved to provide day care services are eligible to participate in CACFP, either independently or as sponsored centers. For-profit centers are eligible to participate only if, in addition, either (1) they receive title XX funds for at least 25 percent of enrolled children or licensed capacity (whichever is less), or (2) at least 25 percent of the children in care are eligible for free and reduced-price meals. Meals served to children are reimbursed at rates based upon a child’s eligibility for free, reduced-price, or paid meals. In centers, participants from households with incomes at or below 130 percent of poverty are eligible for free meals, while those with household incomes between 130 and 185 percent of poverty are eligible for meals at a reduced price (USDA/FNS, 2010b).

Adult Day Care

Public or private nonprofit adult day care facilities that provide structured, comprehensive services to nonresident adults who are functionally impaired or ages 60 years and older may participate in CACFP as either independent or sponsored centers. For-profit centers may be eligible for CACFP if at least 25 percent of their participants receive benefits under title XIX or title XX. Meals served to adults receiving care are reimbursed at rates based upon a participant’s eligibility for free, reduced-price, or paid meals as defined above (USDA/FNS, 2010b).

Family or Group Day Care Homes for Children

Family or group day care homes (referred to as “homes”) are private and must be sponsored by an organization that assumes responsibility for ensuring compliance with federal and state regulations and that acts as a conduit for meal reimbursements to family day care providers. Both family and group day care homes must meet state licensing requirements, where these are imposed, or be approved by a federal, state, or local agency. Group day care homes must be licensed or approved to provide day care services. It is each state’s licensing or approval requirements that distinguish a family from a group home.

Homes enroll an average of eight children, including a provider’s own children. On average, seven enrolled children are in care in a home on a daily basis. Centers enroll more children than homes. On average, a center that enrolls 60 to 70 children will have 53 to 57 children in attendance daily (USDA/FCS, 1997). Food preparation facilities vary greatly just as kitchens do in homes across the socioeconomic spectrum. Many providers have limited education, but others may have college degrees. In some areas, a substantial number of the providers are not fluent in English. Many providers have incomes at or below the poverty level. The day care home may be a major income source for some providers (USDA/FCS, 1997).

“At-Risk” Afterschool Care Programs

Community-based programs that offer enrichment activities for at-risk children and youth after the regular school day ends may be eligible to provide snacks through CACFP at no cost to the participants. Programs must be offered in areas where at least 50 percent of the children are eligible for free and reduced-price meals based upon school data. Reimbursable suppers are also available to children in eligible afterschool care programs in Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and the

District of Columbia (USDA/FNS, 2010b). The effective date of the final rule to add suppers was May 3, 2010 (USDA/FNS, 2010c).

Emergency Shelters

Public or private nonprofit emergency shelters that provide residential and food services to homeless children have been eligible to participate in CACFP since July 1, 1999. Eligible shelters may receive reimbursement for serving up to three meals each day to homeless children, through age 18, who reside there. A shelter does not have to be licensed to provide day care, but it must meet any health and safety codes that are required by state or local law (USDA/FNS, 2010b).

CLIENT CHARACTERISTICS

Age Groups

Section 226.2 of the USDA regulations describes who may receive CACFP meal benefits. Participants must meet the following criteria:

-

Children ages 12 years and under, or ages 15 years and under who are children of migrant workers;

-

For emergency shelters, persons ages 18 years and under;

-

For at-risk afterschool care centers, persons ages 18 years and under at the start of the school year;

-

Persons of any age who have one or more disabilities, as determined by the state, and who are enrolled in an institution or child care facility serving a majority of persons who are ages 18 years and under;

-

Provider’s own children only in a specific low-income situation called tier I day care homes (see description in the section “Meal Reimbursements”) and only when other nonresidential children are enrolled in the day care home and are participating in the meal service; and

-

Adult participants who are functionally impaired or 60 years of age or older and who remain in the community (USDA/FNS, 2010b).

HISTORY AND GROWTH OF THE PROGRAM

In 1968, CACFP began as a small 3-year pilot program called the Special Food Service Program for Children. It arose as part of an effort to create an affordable food program for low-income working mothers. Initially, the program provided grants to states to serve meals when schools were not in session. Table 2-2 shows the chronological development and legislative milestones of CACFP. Of special note are (1) the expansion of eligibility, in 1976, to family child care homes that either meet state licensing requirements

TABLE 2-2 Timeline of the Child and Adult Care Food Program

or obtain approval from a state or local agency; (2) the provision of financial incentives through P.L. 95-627, in 1978, to expand participation; (3) the change from pilot program status to the permanent Child Care Food Program, also in 1978; and (4) authorization for the adult care component following the enactment of the Older Americans Act of 1987, which resulted in the renaming of the program to the Child and Adult Care Food Program.

CACFP has expanded greatly since its inception as a pilot program (USDA/FNS, 2010d), both in terms of the number of participants served and the types of care programs that are eligible. CACFP currently serves more than 3 million children and adults across the United States and two of its territories: Puerto Rico and Guam. Table 2-3 summarizes key information about program characteristics and program participation and illustrates the diversity of settings and the broad reach of the program.

ADMINISTRATION AND REGULATIONS

Overview

CACFP is authorized by Section 17 of the National School Lunch Act (42 U.S.C. 1766). Regulations for program administration are issued by USDA under 7 C.F.R. Part 226. The CACFP program is administrated by USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service through grants to states. At the state level, the state education agency is the usual administrator. In a few states, CACFP is administered by an alternate agency, such as the state health or social services department. The child care component and the adult day care component of CACFP may be administered by different agencies within a state at the discretion of the governor. Independent centers and sponsoring organizations enter into agreements with their administering state agencies to assume administrative and financial responsibility for CACFP operations. Day care homes may participate in the CACFP only under the auspices of a sponsoring organization. Several types of organizations, such as community action agencies and nonprofit organizations, are approved by states to serve as sponsors. Sponsoring organizations provide payment to sponsored day care providers for meals and snacks that meet requirements and are allowed nonfood meal services. The following discussions cover requirements for current meal patterns and key aspects of meal reimbursement.

Current Meal Patterns

CACFP facilities must follow the current meal patterns to receive reimbursement for the meals. The meal patterns for children and adults make use of up to four meal components:

-

Fluid milk,

-

Fruits/vegetables,

TABLE 2-3 CACFP Program Characteristics and Participation by Provider Type for Fiscal Year 2008, Listed in Descending Order by Average Number of Participants per Month

|

Provider Type |

Participant Characteristics |

Licensure |

Reimbursement Options |

Number of Providers |

Number of Participants Served |

|

Child care centers |

Children ages 12 years and younger |

Licensed or approved |

2 meals and 1 snack; or 2 snacks and 1 meal |

39,615 |

1,860,498 |

|

Family day care home |

Children ages 12 years and younger |

Licensed or approveda |

2 meals and 1 snack; or 2 snacks and 1 meal |

141,549 |

849,568 |

|

At-risk after school care facility |

Children ages 18 years and younger |

Approved |

1 snack; or 1 snack and 1 mealb |

6,686 |

300,008 |

|

Outside school hours care facility |

Children ages 12 years and younger |

Licensed or approved |

2 meals and 1 snack |

3,131 |

125,467 |

|

Adult care facility |

Adults ages 60 years and over and disabled adults |

Licensed or approvedc |

2 meals and 1 snack; or 2 snacks and 1 meal |

2,568 |

108,192 |

|

Shelters |

Children ages 18 years and younger |

None |

3 meals; or 2 meals and 1 snack |

398 |

7,958 |

|

aEach state has licensing or approval requirements that distinguish family from group homes and establish maximum participation based on the ratio of infants and children to adults. bAt this time, both one snack and one meal are allowed only in 13 states and the District of Columbia. cDependent on state and local rules for adult day care. SOURCE: USDA/FNS, 2009. |

|||||

-

Grain/bread, and

-

Meat/meat alternates.

As described below, the combination of meal components differs for breakfast, lunch/supper, and snacks; the minimum required amounts of the meal components differ by age group and, for children and adults, by eating occasion.

Meal Pattern Descriptions

Meal patterns for infants differ markedly from those for children and adults, as shown below.

Infants The current infant lunch/supper meal patterns appear in Table 2-4. Ranges are given because of the wide variability in infants’ needs based on developmental stage and readiness for foods.

Children and adults For children, a general description of the current minimums required in the meal and snack patterns follows. The general meal pattern description for adults is identical to the list given below except that a serving of milk is not required at supper.

TABLE 2-4 Current Infant Meal Pattern for Lunch or Supper

|

Food Components |

Birth through 3 Months |

4–7 Months |

8–11 Months |

|

4–6 |

4–8 |

6–8 |

|

|

|

0–3e |

2–4 |

|

|

Fruit or vegetable or both (T) |

|

0–3e |

1–4 |

|

Meat or meat alternated |

|

|

|

|

Meat, fish, poultry, egg yolk, cooked dry beans or peas (T) |

|

|

1–4 |

|

Cheese (oz) |

|

|

½–2 |

|

Cottage cheese (oz, volume) |

|

|

1–4 |

|

Cheese food or cheese spread (oz, weight) |

|

|

1–4 |

|

NOTE: fl oz = fluid ounce; oz = ounce; T = tablespoon. aInfant formula and dry cereal must be iron-fortified. bBreast milk or formula, or portions of both, may be served; however, breast milk is recommended from birth through 11 months. cFor some breastfed infants who regularly consume less than the minimum amount of breast milk per feeding, a serving of less than the minimum amount of breast milk may be offered, with additional breast milk offered if the infant is still hungry. dMenu may include infant cereal, a meat/meat alternate, or both. eA serving of this component is required when the infant is developmentally ready to accept it. SOURCE: Adapted from USDA/FNS, 2010a. |

|||

-

Breakfast: one serving each of milk, fruit or vegetable, and grain or bread (three meal components)

-

Lunch and Supper: one serving each of milk, grain or bread, meat/meat alternate, and two different servings of fruit or vegetable or a combination of fruit and vegetable (four meal components)

-

Snacks: one serving selected from each of two of the four meal components (milk, fruit or vegetable, grain or bread, or meat/meat alternate)—that is, two of the four components.

Serving sizes for children and adults differ by age group, as shown in Table 2-5 for breakfast and in Appendix E for all the other meals and snacks by age group. For children over 12 years of age and adults, the pattern is the same as for children 6–12 years of age with allowance for larger servings. For example, one serving of bread for children ages 1 through 5 years is one-half slice, whereas it is one full slice for children ages 6 through 12 years and may be more for adults. The patterns shown in Table 2-5 and Appendix E include specifications for the types of foods that make up each meal component and the amount of each type of food that represents one serving. Notably, only adult day care centers currently have the option to use the offer versus serve form of food service. In this form of service, participants may refuse to take one or more of the meal components offered to them.

By following the breakfast pattern for children 3–5 years of age, a breakfast menu under the current regulations might include one-third cup

TABLE 2-5 Current Child Meal Patterns for Breakfast: Select All Three Meal Components for a Reimbursable Meal

|

Meal Components |

1–2 Years |

3–5 Years |

6–12 Yearsa |

|

1 Milk (c) |

½ |

¾ |

1 |

|

1 Fruit/vegetable |

|

|

|

|

Juice,b fruit, and/or vegetable (c) |

¼ |

½ |

½ |

|

1 Grain/breadc |

|

|

|

|

Bread (slice) |

½ |

½ |

1 |

|

Cornbread, biscuit, roll, or muffin (svg) |

½ |

½ |

1 |

|

Cold dry cereal (c) |

¼ |

⅓ |

¾ |

|

Hot cooked cereal (c) |

¼ |

¼ |

½ |

|

Pasta noodles, or grains (c) |

¼ |

¼ |

½ |

|

NOTE: c = cup; svg = serving. aChildren ages 12 years and older may be served larger portions based on their greater needs. They may not be served less than the minimum quantities listed in this column. bFruit or vegetable juice must be full-strength. cBreads and grains must be made from whole grain or enriched meal or flour. Cereal must be whole grain or enriched or fortified. SOURCE: Adapted from USDA/FNS, 2010a. |

|||

corn flakes with one-half cup sliced banana and three-quarters cup of whole milk (part on the cereal and part in a cup).

The meal components for CACFP were established when the program began in 1968 as the Special Food Service Program for Children. Changes to the regulations for CACFP governing the required meal components in the meal patterns were established by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-193). The mandated changes included a reduction in the number of meals eligible to be claimed for reimbursement to a maximum of two meals and one snack or one meal and two snacks, regardless of the length of time a child was in attendance (see Table 2-3, “Reimbursement Options” column). The CACFP regulations only provide broad nutrient standards for meals or snacks. Useful benchmarks for assessing nutrient standards for CACFP meals and snacks were examined in the Early Childhood and Child Care Study carried out for USDA (USDA/FCS, 1997). These benchmarks came from the school-based programs (7 C.F.R., Parts 210 and 220), which currently call for breakfast to offer at least one-fourth of the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) and for lunch to provide at least one-third of the RDA for these nutrients. Benchmarks for food energy from total fat, saturated fat, and carbohydrate, as well as the total amounts of cholesterol and sodium in the meals and snacks offered, were derived from recommendations in the 1995 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (HHS/USDA, 1995) and the Diet and Health report (NRC, 1989) (USDA/FCS, 1997).

Meal Reimbursements

Eligible program providers receive reimbursement for meals and snacks served if the meals and foods meet the requirements specified in the regulations (USDA/FNS, 2010a,d,e). The CACFP reimbursement system does not provide partial credit for meals or snacks that meet most of the requirements; they must meet all requirements specified in the meal patterns (see Chapter 7).

Reimbursement Methods

Centers Reimbursement for center-based CACFP facilities is computed by claiming percentages, blended per meal rates, or actual meal count by type (breakfast, lunch, supper, or snack) and considering the eligibility category of participants (free, reduced-price, and paid), which is determined by participant family size and income. As stated above, participants from households with incomes at or below 130 percent of poverty are eligible for free meals. In centers, participants with household incomes between 130 and 185 percent of poverty are eligible for meals at a reduced price (USDA/

FNS, 2010b). The state agency assigns a method of reimbursement for centers, based on meals multiplied by rates, or the lesser of meals multiplied by rates versus actual documented costs. The current reimbursement rates for centers are delineated in Table 2-6; the rates are updated annually.

CACFP centers may operate as pricing or nonpricing programs. Non-pricing programs charge a single fee to cover tuition, meals, and all other day care services; pricing programs charge separate fees for meals. Generally, most CACFP centers, including Head Start programs, operate as nonpricing programs.

TABLE 2-6 Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) Reimbursement Rates per Meal by Meal Type for Adult and Child Day Care Centers, Homes, and Sponsoring Organizations of Day Care Homes, July 1, 2010, through June 30, 2011

|

|

|

Contiguous States |

Alaska |

Hawaii |

|

|

|

Whole or Fractions of U.S. Dollars |

||

|

Centers |

|

|

|

|

|

Breakfast |

Paid |

0.26 |

0.39 |

0.30 |

|

|

Reduced |

1.18 |

2.06 |

1.42 |

|

|

Free |

1.48 |

2.36 |

1.72 |

|

Lunch and supper |

Paid |

0.26 |

0.42 |

0.30 |

|

|

Reduced |

2.32 |

4.01 |

2.78 |

|

|

Free |

2.72 |

4.41 |

3.18 |

|

Snack |

Paid |

0.06 |

0.11 |

0.08 |

|

|

Reduced |

0.37 |

0.60 |

0.43 |

|

|

Free |

0.74 |

1.21 |

0.87 |

|

Day Care Homes |

|

|

|

|

|

Breakfast |

Tier Ia |

1.19 |

1.89 |

1.38 |

|

|

Tier IIb |

0.44 |

0.67 |

0.50 |

|

Lunch and supper |

Tier Ia |

2.22 |

3.60 |

2.60 |

|

|

Tier IIb |

1.34 |

2.17 |

1.57 |

|

Snack |

Tier Ia |

0.66 |

1.07 |

0.77 |

|

|

Tier IIb |

0.18 |

0.29 |

0.21 |

|

NOTE: These rates do not include the value of commodities (or cash in lieu of commodities) that some facilities receive as additional assistance for each lunch or supper served to participants under CACFP. The national average minimum value of donated food, or cash in lieu thereof, per lunch and supper under CACFP (7 C.F.R. Part 226) will be 20.25 cents for the period July 1, 2010, through June 30, 2011 (USDA/FNS, 2010f). aTier I homes are those located in low-income areas or run by providers with family incomes at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty guideline (USDA/FNS, 1997). bTier II homes are those that do not meet either the location- or provider-income criterion for a tier I home (USDA/FNS, 1997). SOURCE: Adapted from USDA/FNS, 2010e. |

||||

Day care homes The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-193) refocused the family child care component of CACFP on low-income children by establishing a two-tier system of reimbursement rates for family child care homes. Tier I day care homes are those that are located in low-income areas, or those in which the provider’s household income is at or below 185 percent of the federal income poverty guidelines. Tier II homes are those family day care homes that do not meet either the location- or provider-income criterion for a tier I home.

Sponsoring organizations may use elementary school free and reduced-price enrollment data or census block group data to determine which areas are low income. However, the provider in a tier II home may elect to have the sponsoring organization identify income-eligible children. When this is done, the meals served to children who qualify for free and reduced-price meals are reimbursed at the higher tier I rates. Program payments for day care homes are based on the number of approved meals served to enrolled children multiplied by the appropriate reimbursement rate (tier I or tier II; see above) for each breakfast, lunch, supper, or snack.

MONITORING THE QUALITY OF CACFP MEALS

Current federal regulations require that state agencies annually conduct monitoring reviews of at least one-third of all CACFP institutions1 and must follow a specific review cycle for sponsors and their sponsored centers and day care homes, with the number of homes monitored based on the home sponsor. The state may conduct additional reviews and/or provide technical assistance for those institutions that need close observation. The purpose of the monitoring is to examine the extent to which the institutions are complying with the CACFP requirements. States monitor the entire CACFP operation, including the ability of child care providers to adequately plan, prepare, and serve a reimbursable meal and to provide nutrition education to its participants. To ensure that the institution meets the CACFP requirements, state monitors also review the institution’s financial viability and financial management systems, internal controls, and other management practices and systems.

Indicators of compliance include record keeping; meal counts; menus; licensing and approval; production records, where applicable; meal observation; administrative costs; and, for sponsor organizations, training and monitoring of their sponsored facilities. States provide technical assistance

as needed, and many combine the monitoring and technical assistance visits. Generally the review covers a specific test month. If further evaluation is warranted, other months may be combined in the review. The state may require the CACFP institutions to develop and submit written corrective action plans to improve and permanently correct any program violations noted during the visit in order to achieve compliance with requirements. If meal deficiencies are observed during the evaluation of the menus (and production records where applicable) and the meal observation, the state may disallow (not reimburse) meals. Because many CACFP institutions have had difficulty completing and maintaining production records that provide enough data to substantiate the validity of the meals produced, several states have eliminated the production record-keeping requirement. In its place, they use receipts and invoices to support the meal reimbursement claims.

CACFP AS PART OF THE FOOD AND NUTRITION SAFETY NET

CACFP is one of 15 nutrition assistance programs administered by the FNS of USDA. These programs provide a safety net for low-income individuals and specific groups that may be vulnerable to social and environmental factors that place them at increased nutritional risk. Of special note, children who consume meals offered through CACFP may also consume food provided through other established nutrition programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children or through the School Breakfast Program (SBP) and the National School Lunch Program (NSLP). Because these are very large programs that serve millions of the nation’s children, it will be especially useful for the CACFP Meal Requirements to align well with the foods and nutrition education provided by these programs.

A new and much smaller program recently introduced by the FNS is the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program, which began as a pilot program in 4 states and is now a nation-wide program in selected schools in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. This program provides fresh fruits and vegetables to low-income children, who may also receive meals through CACFP (USDA/FNS, 2010g). Appendix F contains brief descriptions of most of these programs and identifies websites that provide more detailed information.

CACFP serves a key role in the U.S. food and nutrition safety net. As such, CACFP is expected to meet a portion of participants’ nutritional needs and to be in alignment with current nutrition policy and guidance, including the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans (HHS/USDA, 2005) and Dietary Reference Intakes. The following briefly addresses concerns

about food insecurity in today’s environment and summarizes CACFP’s potential contribution to the nutrition of individuals in day care.

Concerns About Food Insecurity

Food insecurity, the uncertainty of having enough food to meet the basic needs of household members, places children at risk for inadequate food and nutrient intake and for impaired or diminished growth. Among both children and adults, food insecurity increases the risk for behavioral and psychosocial dysfunction (Miller et al., 2008) and poor health outcomes, including infant and toddler development (Biros et al., 2005; Kirkpatrick et al., 2010; Rose-Jacobs et al., 2008; Stuff et al., 2004). The monitoring of food insecurity across the nation by USDA indicates that, as of 2007, the prevalence of food insecurity among children was 8.3 percent and was 11.1 percent for households (USDA/ERS, 2009a). By the end of 2008, the prevalence of household food insecurity had increased to 14.6 percent, the highest prevalence since data collection began in 1995 (USDA/ERS, 2009b).

A high proportion of children served by CACFP can be considered vulnerable to food insecurity because they are from low-income households. However, economic status alone does not predict “hunger” or food insecurity. Adult participants may be vulnerable to food insecurity for another reason: functional impairments may limit their ability to obtain, store, and prepare enough food to meet their needs. Taken together, the population served by CACFP may be considered at higher risk for food insecurity and its associated outcomes than the general population.

Potential Impact of CACFP on Client’s Food and Nutrient Intake

Considering the U.S. population as a whole, CACFP makes a much greater contribution to the food and nutrient intakes of the nation’s children, especially its young children, than it does to its adults. The potential impact of CACFP on individuals in day care settings that participate in the program, whether children or adults, depends on the number of hours spent in day care and thus the amount of food they are served. The discussion below covers participation in day care and the potential contribution of calories from meals served during day care.

Child Care Participation

Overview The document America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being estimates that 36 percent of the U.S. child population ages 0–6 years are cared for in center-based programs that include child care centers,

Head Start programs, publicly funded pre-kindergarten, and private child care (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2009).

As discussed in Chapter 1, family day care homes and traditional child care centers comprise the majority of CACFP providers (more than 93 percent). Preschool children, the largest age group in full-day care, were reported by the U.S. Census Bureau to spend about 32 hours per week in care of any type. According to the 2006 Survey of Income and Program Participation, the number of children younger than 5 years of age reported in all child care arrangements in the United States was about 12.7 million (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006).

Ethnic and socioeconomic considerations Data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate there are substantial ethnic and socioeconomic differences among children enrolled in different types of day care programs. Enrollment data from 2004 by racial and ethnic group showed that about 25 percent of black, Asian, and non-Hispanic white children of working mothers were enrolled in day care. By comparison, only 5 percent of children of Hispanic working mothers were enrolled in day care. Hispanic mothers were twice as likely as non-Hispanic white mothers to rely on relatives, including siblings, for care of their preschool children (19 vs. 7 percent, respectively; U.S. Census Bureau, 2006). Enrollment in day care programs is 10 percent greater for children from families with incomes above the federal poverty level than for children from families in poverty, whose children are more likely to be cared for by a sibling (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006).

Meals in day care Child day care homes provided 497.5 million meals in fiscal year (FY) 2010 and child day care centers provided 1.1 billion meals during that same period (USDA/FNS, 2010h, Table 13a). The committee was unable to locate current program-wide data on average meals served to participants per unit of time by age group. To try to provide some perspective, the very limited available information on CACFP’s contribution to children’s nutrition is summarized below.

Analysis of survey data gathered in 1999 from parents or guardians of children served by CACFP family day care homes found that children in tier II homes would likely consume 50 percent of their daily energy requirements from the breakfast-lunch-one-snack-meal combination and two-thirds from the breakfast-lunch-two-snack-combination (USDA/ERS, 2002).

Children in afterschool programs, who are typically in care for a minimum of 2 hours a day, generally receive only one snack—a small fraction of their daily food needs. These participants, however, may have been provided slightly more than half of their daily food needs through the SBP and the NSLP combined. Those children in the afterschool programs that

are allowed to receive supper in addition to a snack would be expected to receive roughly one-third of their daily calorie requirements from CACFP.

Adult Day Care Participation

According to the National Adult Day Services Association, 3,500 adult day care facilities across the United States are caring for approximately 150,000 adults daily (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2007). USDA surveys indicate that adult day care centers provided 56 million meals to participants in FY 2010 (USDA/FNS, 2010h, Table 15b). Based on the current CACFP meal pattern, adults in day care have the opportunity to meet approximately two-thirds of their calorie needs while attending adult day care centers that provide CACFP services.

SUMMARY

To contribute to the health of persons in day care, the Child and Adult Care Food Program subsidizes the cost of nutritious meals and snacks to participating independent day care centers and, through sponsoring organizations, to other centers and day care homes. More than 3 million children and adults are served through CACFP yearly. To receive reimbursement for the foods served, participating sites are required to provide meals and snacks that meet minimum requirements. The current requirements specify which meal components (fruit/vegetables, grains, meat/meat alternates, milk) must be included in the meals and snacks and the minimum amounts of each. Especially for the infants, children, and adults that are in day care for much of the day, CACFP provides a large majority of their daily food and nutrient intake and makes a major contribution to the food and nutrition safety net.

REFERENCES

Biros, M. H., P. L. Hoffman, and K. Resch. 2005. The prevalence and perceived health consequences of hunger in emergency department patient populations. Academic Emergency Medicine 12(4):310–317.

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. 2009. America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. http://www.childstats.gov/pdf/ac2009/ac_09.pdf (accessed September 28, 2010).

HHS/USDA. 1995. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. http://www.health.gov/DIETARYGUIDELINES/dga95/default.htm (accessed December 16, 2010).

HHS/USDA (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2005. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 6th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. http://www.health.gov/DietaryGuidelines/dga2005/document/ (accessed July 23, 2008).

Kirkpatrick, S. I., L. McIntyre, and M. L. Potestio. 2010. Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 164(8):754–762.

Miller, E., K. M. Wieneke, J. M. Murphy, S. Desmond, A. Schiff, K. M. Canenguez, and R. E. Kleinman. 2008. Child and parental poor health among families at risk for hunger attending a community health center. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 19(2):550–561.

NRC (National Research Council). 1989. Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease Risk. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2007. National Adult Day Services Association Becomes Independent Organization, Expands Outreach through New Materials, Conferences and Member Hotline. http://www.rwjf.org/reports/grr/040623.htm (accessed August 11, 2010).

Rose-Jacobs, R., M. M. Black, P. H. Casey, J. T. Cook, D. B. Cutts, M. Chilton, T. Heeren, S. M. Levenson, A. F. Meyers, and D. A. Frank. 2008. Household food insecurity: Associations with at-risk infant and toddler development. Pediatrics 121(1):65–72.

Stuff, J. E., P. H. Casey, K. L. Szeto, J. M. Gossett, J. M. Robbins, P. M. Simpson, C. Connell, and M. L. Boglet. 2004. Household food insecurity is associated with adult health status. Journal of Nutrition 134(9):2330–2335.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2006. Survey of Income and Program Participation. http://www.census.gov/sipp/index.html (accessed July 11, 2010).

USDA/ERS (Economic Research Service). 2002. Households with Children in CACFP Child Care Homes—Effects of Meal Reimbursement Tiering: A Report to Congress on the Family Child Care Homes Legislative Changes Study. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/efan02002/efan02002.pdf (accessed October 11, 2010).

USDA/ERS. 2009a. Food Insecurity in Households with Children: Prevalence, Severity, and Household Characteristics. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib56/eib56.pdf (accessed March 25, 2010).

USDA/ERS. 2009b. Household Food Security in the United States, 2008. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err83/err83.pdf (accessed September 27, 2010).

USDA/FCS (Food and Consumer Service). 1997. Early Childhood and Child Care Study: Nutritional Assessment of the CACFP: Final Report, Volume 2. Alexandria, VA: USDA/FCS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/ora/menu/Published/CNP/cnp-archive.htm (accessed July 9, 2010).

USDA/FNS (Food and Nutrition Service). 1997. Child and Adult Care Food Program; Improved Targeting of Day Care Home Reimbursements. Federal Register 62(4):889–915.

USDA/FNS. 2000. Building for the Future in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP). http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/care/publications/pdf/4Future.pdf (accessed June 29, 2010).

USDA/FNS. 2009. Child and Adult Care Food Program: Building for the Future. PowerPoint presentation at the open session of the IOM committee on December 8, Washington, DC.

USDA/FNS. 2010a. Child and Adult Care Food Program Meal Patterns. http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/care/Program Basics/Meals/Meal_Patterns.htm (accessed March 24, 2010).

USDA/FNS. 2010b. Child and Adult Care Food Program. http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/care/cacfp/aboutcacfp.htm (accessed July 9, 2010).

USDA/FNS. 2010c. Child and Adult Care Food Program: At-Risk Afterschool Meals in Eligible State. Federal Register 75(62):16325–16325.

USDA/FNS. 2010d. Child and Adult Care Food Program Legislative History. http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Care/Regs-Policy/Legislation/history.htm (accessed March 24, 2010).

USDA/FNS. 2010e. Child and Adult Care Food Program: National Average Payment Rates, Day Care Home Food Service Payment Rates, and Administrative Reimbursement Rates for Sponsoring Organizations of Day Care Homes for the Period July 1, 2010 Through June 30, 2011. Federal Register 75(137):41793–41795.

USDA/FNS. 2010f. Food Distribution Program: Value of Donated Foods From July 1, 2010 Through June 30, 2011. Federal Register 75(137):41795.

USDA/FNS. 2010g. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program. http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/FFVP/FFVPdefault.htm (accessed March 24, 2010).

USDA/FNS. 2010h. Program Information Report (Key Data) U.S. Summary, FY 2009–FY 2010. http://www.fns.usda.gov/fns/key_data/july-2010.pdf (accessed October 19, 2010).