1

Introduction

While the goal of the workshop was neither to reach consensus on any single issue nor make specific recommendations about how to resolve any of these issues, several main themes emerged over the course of the one-and-a-half-day dialogue. This chapter provides an overview of the major themes of the workshop presentations as well as a summary of Stephen Sundlof’s introductory presentation. The workshop presentations encompassed a wide range of themes from the current state-of-the-science on aging populations to potential opportunities and directions for the future. For one, America’s aging population is actually many different aging populations (i.e., with respect to age but also socioeconomic status, level of family support, etc.). On the other hand, some presenters noted that although stakeholders across sectors are increasing their focus on food safety, nutrition, and food communication with older adults, there is both a need and opportunity for these different stakeholders to join forces and collaborate in ways that could accelerate progress. Sundlof’s presentation focused largely on actions that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already taken or is planning for the future with respect to improving not just food safety but also nutrition. Many of those actions revolve around nutrition labeling on packaged foods. Actions aimed at improving dietary choices among older adults in particular include conducting age-related risk assessments and developing educational materials and messages aimed at older adults.

MAIN THEMES OF WORKSHOP DISCUSSION

Again, while the goal of the workshop was neither to reach consensus on any single issue nor make specific recommendations about how to resolve any of these issues, several overarching themes emerged from the workshop presentations:

-

Government, private industry, and academia are all increasing their focus on food safety, nutrition, and communication in older adults. In his overview, Sundlof described various FDA initiatives aimed at improving food safety and nutrition in older adults. Later, a wide range of other government, academic, and industry representatives discussed the variety of ways that different stakeholders are embracing the challenge of improving food safety and nutrition in aging populations.

-

America’s aging population is actually many aging populations. As Kevin Kinsella discussed during his presentation, there is tremendous heterogeneity in the U.S. population of adults more than 65 years old with respect not just to age (e.g., 65-and-over vs. 85-and-over) but to race, socioeconomic status, level of family support, disability, chronic health conditions, and other factors. This theme was revisited several times during the workshop and in several different contexts. For example, as discussed during the session on changes in physiology with age (see Chapter 3), the sensory and physiological changes that accompany aging and the implications of these changes with respect to both food safety and nutrition can be dramatically different between someone in his or her fifties versus someone who is 80 years of age or older. As people age, their susceptibility to certain foodborne illnesses changes, as does their overall nutritional status. As another example, discussed at length during the final session of the workshop (see Chapter 7), older adults have varying levels of family support. The majority of older adults live in the community, raising important questions about the strength (or, as one participant questioned, the existence) of the infrastructure in place for providing nutrition services to these adults. Simultaneously, the fact that a small but significant percentage of older adults live in assisted living facilities or other settings also raises equally important questions about the quality of nutritional services that this segment of the older population is receiving.

-

Aging is a lifetime process. Related to the previous themes, there were several remarks about how aging begins during early development and not at any particular age later in life. For example, Luigi Fontana elaborated on this notion during his presentation on caloric

-

restriction. It was suggested that when discussions occur around aging, it should be clearly stated what particular age group is under consideration.

-

Aging is accompanied by a wide range of physiological changes, with varied implications for what can and should be done to improve food safety and nutrition in older adults. For example, Simin Meydani elaborated on how the immune system changes with age, making older adults more susceptible to infectious disease and presented evidence from several studies suggesting that nutritional manipulation could decrease susceptibility to infection in older adults. Steven Gendel argued, on the other hand, that there is more to infection than an impaired immune system. He described evidence showing that not all foodborne pathogens are of concern and that susceptibility varies, with some microbes of greater concern than others. He emphasized that while monitoring for disease incidence can have a significant public health impact, it is important to recognize that there are two factors to consider when determining whether a food-borne pathogen poses a risk to older adults and that the two factors are not necessarily linked—(1) incidence and (2) severity of illness. Gordon Jensen discussed that while most of the gastrointestinal (GI) system remains largely intact as people age, with most serious dysfunction being related to an underlying health condition, the one component of GI function that does tend to degrade with aging is oral health (e.g., changes in dentition and swallowing). Not only does impaired oral health lead to poor diet quality and micronutrient deficiencies, periodontal disease in particular has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Finally, Marcia Pelchat described how three different sensory perceptions (taste, olfaction, and “chemical feeling”) change with age and impact eating. For example, pleasant flavors becoming less pleasant and unpleasant flavors becoming less unpleasant, the latter leading to a loss of taste’s gate-keeping function for protecting the body (e.g., the ability to detect food spoilage or salt).

-

While industry has made tremendous progress in developing new food processing techniques and novel packaging that minimize many food safety problems, there are still important unanswered questions about how food processing, formulation, and packaging can be improved to better meet the needs of older adults. Michael Doyle discussed some of the innovative food processing technologies that have been designed to protect food and minimize contamination and other food safety problems, as well as some of the challenges that still exist. Aaron Brody described the wide range of packaging technologies designed to do the same. Brody’s talk in particular

-

prompted several questions about some of the challenges that still exist with respect to developing innovative packaging that works well for older consumers.

-

While most of the workshop participants who commented on the issue agreed that high quality diets and nutrient optimization are necessary for maintaining good health in older adults, several questions remain about exactly what constitutes a high quality diet (e.g., should older adults eat more or less protein?) and obstacles to obtaining that optimal diet (e.g., poor oral health, loss of appetite). Katherine Tucker discussed how dietary needs change with age and identified some of the challenges with meeting those needs; Stephen Barnes discussed functional foods (i.e., foods that promote health) and bioavailability challenges for older adults; and Luigi Fontana discussed the role of caloric restriction in regulating many biological factors known to be associated with aging.

-

There are many unanswered research questions and a lack of data around food safety and nutrition concerns in older adults. Lack of data is a serious problem not just with respect to gaining a better understanding of the nutritional needs of older adults but for many other issues as well. For example, in the final session of the workshop (see Chapter 7), Steven Gendel remarked that one of the challenges with differentiating among multiple aging populations is the lack of health monitoring data and the consequent inability to generate enough statistical power to make conclusions about the health conditions and needs of those varied populations. As another example, Bernadene Magnuson presented recent findings on the adverse effects of soy and curcumin and argued that many active ingredients in dietary supplements are understudied and may have unknown safety risks. David Greenblatt, on the other hand, in his telling of “the grapefruit story” (how grapefruit juice interacts with some drugs), argued that ample data on CYP3A (the enzyme responsible for the grapefruit juice-drug interaction) implicate only very few interactions between food in general and drugs.

-

Communication is an important component of improving nutrition in older adults, with many ongoing industry-sponsored programs aimed at elucidating the best way to communicate about nutrition to older adults. For example, Steven Bodhaine described what a recent wellness segmentation study revealed about how older adults view health and food, emphasizing the need to engage consumers on a personal level. Jim Kirkwood described the results of studies that General Mills has conducted in an effort to learn what drives consumers’ food choices, emphasizing the importance of combining scientific facts about nutrition with “the things that really matter

-

to consumers” when developing and marketing new food products. More generally, Ronni Chernoff listed and described the key elements of effective written and oral communication.

-

Similarly, communication is an important component of improving food safety in older adults, and there are many unanswered questions around how to best communicate about food safety issues with older adults. William Hallman discussed lessons learned from recent surveys on how people respond to food recalls and emphasized the need to “get it right,” given that food recalls are likely to become even more frequent in the future as the food supply continues to expand (globally) and food surveillance technologies continue to advance. Caroline Smith DeWaal emphasized the potential value of on-the-spot messaging when communicating urgent food safety messages to older adults, as well as the value of restaurant grading systems. Both talks prompted several questions about the need to devise new means of risk communication when a recall or other urgent food safety event arises.

-

Most older adults live in the community, not in nursing homes or other institutional settings, and there is some concern that the infrastructure currently in place is insufficient for meeting the food safety and nutrition needs of this population. Nancy Wellman elaborated on this reality and its implications during her presentation. The theme was revisited at length in the final panel session. At the same time, a smaller but significant proportion of the aging population, particularly the 85-and-over population, live in assisted living or other institutional settings, and some participants expressed concern about the quality of nutritional services that they are receiving.

-

There is enormous opportunity for collaboration between the food and food packaging industries and other food safety and nutrition stakeholders (academia, government, consumer groups) in efforts to address some of the most pressing food safety and nutrition issues in aging populations. Suzie Crockett and several other participants touched on this theme throughout the workshop, citing examples of the ways that the U.S. government, industry, and the traditionally separate food safety and nutrition communities are already working together or could be working together to develop food products that meet the changing nutritional needs of older adults, devise new ways to communicate about food safety and nutrition to older adults, and tackle other pressing food safety and nutrition issues.

See Chapter 7 for a more detailed summary of some of these and other topics that were highlighted in the final session of the workshop, when four distinguished panelists were asked to comment on what they considered to

be the most important issues and future challenges to providing healthy and safe foods to aging populations.

OVERVIEW OF THE CHALLENGES TO ENSURING SAFE AND NUTRITIOUS FOODS FOR AGING POPULATIONS

Presenter: Stephen Sundlof

Stephen Sundlof of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) at FDA began by remarking on the necessity of accounting for aging populations when considering food safety. As such, FDA is increasingly taking aging into account when deliberating on food safety issues. FDA is also intensifying its focus on nutrition and has initiated or is planning many actions aimed at helping Americans of all ages make better dietary choices. The remainder of Sundlof’s presentation focused on FDA’s activity around nutrition.

First, he listed some pertinent facts about the current state of nutrition in the United States:

-

Two-thirds of Americans are overweight or obese. Recent data indicate older adults, ages 50 to 69, are even more affected (Ogden et al., 2006; CDC, 2010).

-

Diet and lifestyle choices are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States (especially from diabetes and heart disease).

-

Most Americans do not meet the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommendations with respect to their intake of fresh fruits and vegetables, which is known to be associated with lowering the risk for diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic diseases.

-

Ninety percent of middle-aged Americans will develop high blood pressure at some point in their life, putting them at risk for hypertension, which can be controlled to some extent through diet.

Most of FDA’s activity around nutrition involves the following:

-

Reviewing and authorizing health claims and nutrient claims on labels so that consumers can make informed choices. FDA monitors about a dozen health claims, which must have sufficient scientific information in order to be considered as such (e.g., soluble fiber lowers cholesterol). The agency also monitors nutrient content claims, which must meet established criteria in order to be identified as such.

-

Educating consumers about which foods comprise a healthful diet and which foods to moderate.

-

Overseeing the labeling on packaged foods so that the information is neither false nor misleading.

Sundlof focused on the last activity: overseeing the labeling on packaged foods.

FDA Activity Around Nutrition: Overseeing Labeling on Packaged Foods

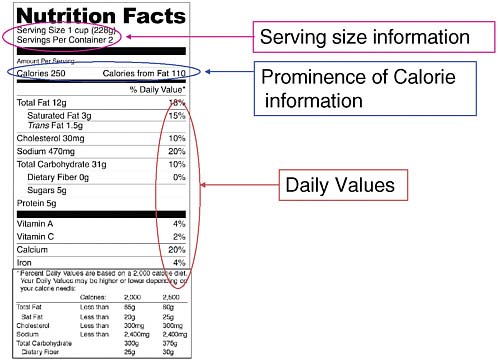

Sundlof identified the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 (NLEA) as one of the most important recent milestones in FDA efforts to improve nutrition. NLEA makes the Nutrition Facts panel mandatory on the packaging of almost all foods, with the exception of individual snacks, fresh produce, and some other products. The panel contains nutrition information that helps consumers make informed choices about the healthfulness of their diets and usually is located on either the side or back of the package (see Figure 1-1). FDA is currently in the process of modernizing the panels

FIGURE 1-1 An example of a mandatory Nutrition Facts panel, with parts of the panel currently under review by FDA highlighted, as described by Sundlof.

based on public response. The agency recently issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking, asking for comments on the panel and where improvements could be made (FDA/HHS, 2007). So far, among other lessons, FDA has learned

-

Serving size information is often confusing, with serving sizes not equal to what people normally eat (e.g., a serving size of tortilla chips might be six chips, but few people sit down and eat only six chips). Many people do not even read the information. Serving size information needs to be improved such that the listed serving size is actually the same as what people normally consume in one sitting, and consumers need to be educated about what serving size means.

-

Most people look at calorie information when seeking nutrition information, therefore FDA is working on ways to make this information more prominent. The agency is also considering eliminating “Calories from Fat” and replacing it with “Percent of Daily Value” information.

-

Daily Values are due for reconsideration to see if they are still accurate, with some changes expected based on new information.

Point-of-Purchase Labeling

Given recent publicity around point-of-purchase labeling, which includes both front-of-package labeling and shelf labeling, Sundlof spoke in detail about measures FDA is implementing in an effort to manage confusing labeling. Food companies are increasingly including nutrition information not just in the Nutrition Facts panel but also on the front of packages given that this information can influence people’s choices about which foods to buy. However, from what FDA has heard from the food industry, retailers, food processors, and others, the information becomes very confusing very quickly.

Front-of-package labels. There are two main types of front-of-package labels used in the United States:

-

Summary symbols, which contain minimal information indicating that the food meets some kind of health criterion (e.g., it is “healthy” or “good for you”). Usually, the product is compared to other products within a product group. For example, many cereals contain symbols indicating that that they are “a better choice” than other cereals. There are a number of different types of front-of-package symbols being used. For example, the “Smart Choices”

-

label, developed by a consortium of private, public health, and academic nutrition leaders, has received much attention recently.1 Just a couple weeks prior to the workshop, the Smart Choices program announced that it would no longer be accepting additional clients. Sundlof explained that, according to a public statement by the U.S. Commissioner of Food and Drugs, Margaret Hamburg, FDA is not fully supportive of the criteria of the Smart Choices program. For example, some cereals have qualified even though their composition is nearly 50 percent sugar. Sundlof said that following Hamburg’s statement, many major food companies announced they would no longer be participating in the Smart Choices program. Also, just prior to the workshop, Hamburg indicated FDA would be looking into developing a single front-of-package system in an effort to minimize the confusion associated with the wide range of labeling systems currently in use.

-

Nutrient specific symbols, whereby the front of the package provides information about specific nutrients (e.g., fiber, sugar, calories).

Sundlof pointed to the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency’s voluntary traffic light system as an example of a different type of front-of-package labeling: symbols that provide both specific nutrition information and gradations about positive or negative levels of fat, saturated fat, salt, and sugars.2 A red light indicates a high level, an amber light a medium level, and green light a low level. Traffic light symbols provide consumers with a lot of information that can be gathered in a glance. Because it is a voluntary system, it tends not to be used for products that would have a lot of red lights. However, because the United Kingdom does not require nutrition fact labeling, this is one of the few ways that consumers can view information about the nutrition content of foods. The system has garnered some attention in the United States and is being considered as a possible option according to Sundlof.

Shelf labeling. Sundlof mentioned the “Guiding Stars” system, developed by Hannaford Supermarkets, as example of shelf labeling: the more stars, the “healthier” the food under Guiding Stars criteria.3

|

1 |

More information about the Smart Choices program, including its nutrition criteria, is available online at http://www.smartchoicesprogram.com/. |

|

2 |

More information about traffic light labeling in the United Kingdom can be found online at http://www.eatwell.gov.uk/foodlabels/trafficlights/. |

|

3 |

More information on the Guiding Stars shelf-tag labeling system is available online at http://www.guidingstars.com/. |

FDA Actions

In an effort to alleviate some of the confusion around point-of-purchase labeling, FDA is

-

analyzing front-of-package labels that appear to be misleading and determining what type of regulatory action needs to be taken to prevent consumers from being misled;

-

reviewing nutrient-specific front-of-package labels to ensure that they are consistent with the regulatory criteria established for the nutrient content claim (e.g., if the label indicates that the food is low fat, the food must be low in fat as defined by FDA);

-

developing a proposed rule to standardize front-of-package labeling and provide consistent criteria for use of the labeling (i.e., whether or not a single front-of-package label is developed, the criteria should nonetheless be consistent); and

-

conducting research on how consumers view and use front-of-package labeling and whether individuals make good diet choices based on labeling (e.g., while consumers are more likely to purchase a product with front-of-package labeling, versus a product without such labeling, it is unclear whether this behavior actually contributes to building a healthier diet).

FDA FOOD SAFETY AND NUTRITION ACTIONS AIMED SPECIFICALLY AT AGING POPULATIONS

FDA is implementing several measures aimed specifically at improving dietary choices among older adults, including the following:

-

Considering age-related issues when conducting safety and risk assessments. For example, when examining a new food additive or responding to the detection of a contaminant, the agency considers not just the general population but also subpopulations and then makes decisions based on the most sensitive subpopulation(s).

-

Monitoring adverse event data for problems affecting specific age groups.

-

Developing educational materials and safety messages aimed at seniors and their caregivers. For example, www.foodsafety.gov (a new website developed by the White House Food Safety Working Group and which contains both U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA] and FDA food safety information) and www.fda.gov provide consumer publications and other information on food safety and nutrition for seniors. For example, among other information FDA’s “Resources for You: Food

-

Safety for Seniors” webpage4 provides senior consumers with a list of foods to avoid: raw fin fish and shellfish (because of the many infectious agents that they can transmit), hot dogs and luncheon meats unless reheated until steaming hot (because of Listeria), raw or unpasteurized milk or soft cheeses (because of Listeria), refrigerated pates or meat spreads (again, because of Listeria), raw or lightly cooked eggs or egg products (because of Salmonella), raw meat or poultry (because of Salmonella), raw sprouts (because of Salmonella, Listeria, and E. Coli), and unpasteurized or untreated fruit or vegetable juice (because of E. coli O157:H7). FDA has also issued a publication, “Using the Nutrition Facts Label: A How-To Guide for Older Adults,” and is developing Fight BAC!5 materials aimed at different age groups.

In conclusion, Sundlof emphasized that FDA is strengthening its focus on nutrition, especially among older adults, and is making a major effort toward improving nutrition labeling so that consumers of all ages can make healthier dietary choices. He stressed that success will depend on a team effort and partnerships between FDA and other agencies and organizations.

QUESTIONS AND DISCUSSION

Sundlof’s presentation prompted several questions about how FDA gathers its consumer information (i.e., with respect to what consumers would like to see on nutrition panels); whether FDA foresees developing a different type of food nutrition labeling for older adults (e.g., with larger font sizes); and how decisions are made about some of the information that is included, or not included, on food labels (e.g., the lack of differentiation among different types of sugars).

How FDA Gathers Consumer Information

Sundlof explained that in addition to having sent notices through the Federal Register requesting input on what changes consumers would like to see on the Nutrition Facts panel and nutrition labels, FDA will also be conducting focus groups and other types of consumer research. He emphasized that FDA cannot impose new rules without consumer research, as the agency bases all of its regulations on science.

|

4 |

Available online: http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/Seniors/ucm182679.htm (accessed August 3, 2010). |

|

5 |

The Fight BAC! campaign is a food safety initiative designed to educate consumers about the four simple practices—clean, separate, cook, and chill—that can help reduce their risk of foodborne illness. The campaign was created by the Partnership for Food Safety Education (PFSE), and Fight BAC! materials can be accessed through www.foodsafety.gov. |

Different Nutrition Labeling for Older Adults?

With respect to whether or not FDA foresees having different types of labels for older adults, Sundlof explained that the Agency’s objective is to make sure that the information on the label is understood by all groups.

How FDA Makes Decisions About Nutrition Label Information

An audience member asked Sundlof whether FDA will be revisiting rounding errors and content claims that declare a product is low fat or zero fat even though it may have, for example, 0.4 grams (g) of fat per serving. Sundlof explained that, generally, even if the level of a nutrient is a fraction of a point below a certain predetermined level, a claim (e.g., “zero fat”) could be made. However, FDA is currently revisiting some of those claims, in particular trans fat levels. Currently, if a product contains less than 0.5 g trans fat per 100 g food, a claim can be made that the product has zero trans fat. As the methodology for trans fat detection has improved since that rule was established, FDA is reconsidering how trans fat free claims are regulated.

Another member of the audience asked about some of the other ingredients, such as high fructose corn syrup, that are not currently included on the Nutrition Facts panel and whether FDA is considering including information about any additional nutrients. Sundlof said that, with respect to sugars, those sorts of distinctions are not made on the Nutrition Facts panel. However, ingredients like high fructose corn syrup do appear on the ingredient list. Additionally, depending on how current development of a new front-of-package labeling system proceeds, that type of information may in the future be included elsewhere on the package as well.

When asked about whether smaller processors might be exempt from any new front-of-package labeling requirements, Sundlof said that, generally, FDA makes exceptions for the Nutrition Facts panel based on certain criteria (e.g., if the product is being sold as an individual snack) and that this will likely be the case for front-of-package labeling.

Finally, there was a question about the legibility and size of the information provided on labels and whether FDA is considering if it is appropriate for aging populations. The questioner remarked, “The best information that is on the label is not usable if it is not legible.” Sundlof explained how FDA currently requires that certain Nutrition Facts panel criteria be met, for example certain information must meet a minimum font size, and FDA will be testing various font sizes and other properties of front-of-package labeling to ensure that different age groups, both older and younger populations, can read the information. He said that one of the challenges with front-of-package labeling, particularly on small packages, is that the package front is “prime real estate.”