4

Initiatives to Advance Patient-Centered Drug Safety

U.S. PHARMACOPEIA HEALTH LITERACY AND PRESCRIPTION CONTAINER LABELING ADVISORY PANEL

Joanne Schwartzberg, M.D.

American Medical Association

The U.S. Pharmacopeia’s (USP’s) Health Literacy and Prescription Container Labeling Advisory Panel was launched after the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Report on Standardizing Medication Labels (IOM, 2008). Schwartzberg co-chairs the panel with Gerald McEvoy, American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists. The panel was charged to (1) determine the optimal prescription label content and format to promote safe medication use by critically reviewing factors that promote or distract from patient understanding of prescription medication instructions, and (2) create universal prescription label standards for format and appearance, content and language. The panel included a wide range of stakeholders: academic researchers, clinicians, health literacy experts, pharmacists, and government health agency representatives.

Medication misuse results in more than a million adverse drug events each year (IOM, 2008). The label is the patient’s best, and often only, source of information. It is the safety net to prevent medication errors. While written information and oral consultations may sometimes be available, the Rx container label must be able to fulfill the professional obligations of physicians and pharmacists to give the patient all the information needed to understand how to safely use the medication.

The panel made its recommendations in November 2009 (USP, 2010). These recommendations are presented in Box 4-1.

The recommendations have been adopted by the Safe Medication Use Committee. USP is preparing a General Chapter for the USP-National Formulary. The patient-centered prescription label standards are for the format, appearance, content, and language of prescription medication containers to promote patient understanding. These recommendations are evidence based and address optimal understanding, adherence, and safe and effective use of medications by patients, Schwartzberg said.

|

BOX 4-1 Recommendations of the U.S. Pharmacopeia Health Literacy and Prescription Container Labeling Advisory Panel Recommendations Organize the Prescription Label in a Patient-Centered Manner Patient-directed information must be organized in a way that best reflects how most patients seek out and understand medication instructions. Prescription container labeling should feature only the most critical patient information needed for safe and effective understanding and use. Patient-directed instructional content will be at the top of the label, and other less critical content (e.g., pharmacy name and phone number, prescriber name, fill date, refill information, expiration date, prescription number, drug quantity, product description, and evidence-based auxiliary information) should not supersede critical patient information. Such less critical information can be placed, e.g., at the bottom of the label or another less prominent location. Drug name and directions for use (e.g., specific dosage/usage/administration instructions) should be displayed with greatest prominence. Simplify Language To improve patient understanding and safe and effective prescription medication use, language on the label should be clear, simplified, concise, and standardized. Only common terms and sentences should be used. Use of unfamiliar words (including Latin terms; see below) and unclear medical jargon should be avoided. Whenever available and appropriate to the patient context, standardized patient-centered translations of common prescribing directions to patients (SIG) should be used. Ambiguous directions such as “take as directed” should be avoided unless clear and unambiguous supplemental instructions and counseling are provided (e.g., directions for use that will not fit on the prescription container label). A clear statement referring the patient to such supplemental materials should be stated on the container label. |

|

Readability formulas and software are not recommended for short excerpts of text like that on prescription labels. The principles established by Doak, Doak, and Root for maintaining simple language can facilitate the simplification process. Consumer feedback should also be sought. Use Explicit Text to Describe Dosage/Interval Instructions Dosage/usage/administration instructions must clearly separate dose from interval and must provide the explicit frequency of drug administration (e.g., “Take 4 tablets each day. Take 2 tablets in the morning and 2 tablets in the evening” is better than “Take two tablets by mouth twice daily”). Use numeric rather than alphabetic characters for numbers. Include Purpose for Use Confidentiality and FDA approval for intended use (e.g., labeled vs. off-label use) may limit inclusion of indications on drug product labels. Current evidence supports inclusion of purpose-for-use language in clear, simple terms. Therefore, the prescriber’s intended purpose of use/indication should be included on the prescription medication label whenever possible and should be stated in clear, simple, patient-centered language. When such use conflicts with unit-of-use commercial packaging information, the patient should receive appropriate counseling to clarify the intended purpose of the medication vs. what is stated in commercial labeling. Improve Readability Critical information for patients must appear on the prescription label in an uncondensed, simple, familiar, minimum 12-point, sans serif font (e.g., Arial) that is in sentence case (i.e., punctuated like a normal sentence in English: initial capital followed by lowercase letters except for proper nouns, acronyms, etc.). Field size and font size may be increased in the best interest of patient care. Critical information should never be truncated. The following several general rules can improve readability:

Highlighting, bolding, and other typographical cues should preserve readability (e.g., contrast, light color for highlighting), and should emphasize patient-centric information or information that facilitates patient adherence. |

|

Provide Labeling in Patient’s Preferred Language Whenever possible, prescription container labeling should be provided in a patient’s preferred language. Translations of prescription medication labels should be produced using a high-quality translation process. An example of a high-quality translation process includes the following four elements:

If a high-quality translation process cannot be provided, labels should be printed in English. Include Supplemental Information Auxiliary information on the prescription container should be minimized and should be limited to evidence-based critical information regarding safe. The information should be presented in a standardized manner and should be necessary for patient understanding. This is necessary because of the extensive variability in the content and application of supplemental information, the lack of scientific evidence for these labels, and potential ambiguity and failure to address specific patient needs. Auxiliary information should be critical to the medicine’s safe and appropriate use and should be evidence-based, should clarify instructions for use, and should enhance understanding. Use of icons should be limited to those for which evidence demonstrates enhancement of interpretation and clarity about use. The inclusion of auxiliary information on the patient prescription medication label (e.g., warnings and critical administration alerts) should be minimized and limited to critical information that is evidence based, standardized, and complementary to the patient prescription medication label. Standardize Directions to Patients In recognition of the nation’s move toward e-prescribing, the HL AP recommends that standards should be developed for prescribing directions to patients (SIGs). This would lead to consistency of language and use across all health care professionals and systems. An important element is the elimination of Latin abbreviations (BID, QID, PRN, etc.), which are often misunderstood and susceptible to variation in translation. SOURCE: USP, 2010. |

NATIONAL COUNCIL ON PATIENT INFORMATION AND EDUCATION

William Ray Bullman, M.A.M.

National Council on Patient Information and Education

The National Council on Patient Information and Education (NCPIE) is a patient safety coalition formed in 1982 to stimulate and improve communication of information on safe and appropriate medicine use to consumers and health care professionals. The NCPIE is a membership organization including a wide range of stakeholder groups; the FDA and AHRQ have nonvoting seats on the board of directors. It is a convener, a catalyst, and a clearinghouse of ideas and information. As a convener, the NCPIE is positioned to serve as a home for collaborations on some of the Safe Use Initiative issues.

NCPIE initiatives include the Get the Answers/I Give the Answers Campaign, which is designed to equip consumers with questions to ask in order to find out what they need to know about prescription medicines. NCPIE also sponsors October as Talk About Prescriptions month. Begun in 1986, this effort is aimed at keeping safe use of medications on the public health agenda. The organization also develops reference reports and stakeholder recommendations and conducts web outreach. The outreach websites are:

-

talkaboutrx.org lists current activities

-

bemedwise.org has an OTC focus

-

mustforseniors.org for older adults and caregivers

-

learnaboutrxsafety.org, a tool kit for families

NCPIE campaigns focus on the three Rs: risk, respect, and responsibility. First, it should be recognized that all medicines have some degree of risk as well as benefit. Second, it is important to respect the value of medicines properly taken, understanding that prescription and OTC medicines are serious and must be taken with care. Third, patients have a responsibility for learning how to take each medicine safely. Being responsible also means following the rule: when in doubt, ask. The NCPIE recommends asking questions about instructions for use, precautions, side effects, warnings, and the availability of written information.

NCPIE also encourages patients to share information about all medications taken (prescription, OTC, and dietary supplements) with doctors, pharmacists, nurses, and other health care professionals; keep a current list of all medicines taken; show the list to the health care professional at every visit; and read carefully any written information that comes with the medicine, being sure to save it for future reference.

Finally, the NCPIE has built expertise and has pilot programs related to adherence improvement. In 2007, it released a national action plan of 10 recommendations to enhance adherence (NCPIE, 2007). The NCPIE will begin tracking progress and gaps and opportunities related to the action plan recommendations. The NCPIE has several collaborations that are ongoing:

-

National Coordinating Council on Medication Error Reporting and Prevention

-

National Consumers League (et al.) to develop national adherence awareness campaign

-

Partnership for a Safer Maryland—current focus on poison prevention (pharmaceuticals focus)

-

Maryland Acetaminophen Coalition

-

Acetaminophen Awareness Coalition

-

Be MedWise Tennessee & Be MedWise Arkansas—statewide outreach and educational programs using licensed NCPIE resources

Mr. Bullman said that although several projects and campaigns exist, there are still areas that need improvement:

-

The current state of written consumer medicine information (consumer medicine information [CMI], med guides, risk evaluation and mitigation strategies [REMS])

-

Provision of useful or actionable written information to special needs patients (e.g., blind and visually impaired)

-

Balanced patient medication counseling when high-risk drugs are prescribed

-

Language–appropriate medicine counseling reinforced with useful written information

CDC INITIATIVE

Daniel Budnitz, M.D., M.P.H.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Dr. Budnitz offered three themes for discussing the intersection of health literacy and safe use. The first is an injury-based approach to safe use of medications. Second involves population-based harm data that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collects and which may be useful for priority setting. The third theme involves a patient-centered prevention partnership called the Protect Initiative.

The injury-based approach identifies the areas with the highest num-

ber of adverse drug events, thereby identifying the highest potential for overall harm reduction. This sounds logical, but it is not how patient safety has been approached. The approach that has been followed is one of error reduction. However, addressing preventable events must be considered as well. The real focus, therefore, is the intersection of errors and harm.

The focus of today’s meeting is on errors related to health literacy and how those might injure patients. The CDC policy was most influenced by the Government Accounting Office (GAO) report Adverse Drug Events: The Magnitude of Health Risk is Uncertain Because of Limited Incidence Data (GAO, 2000). The GAO determined that data available on emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions are insufficient for estimating the frequency of adverse drug events. In response, CDC created the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance Project (NEISS-CADES). This system documented at least 117,000 hospitalizations and more than 700,000 ED visits due to adverse drug events in 2004 and 2005 (Budnitz et al., 2006). More recent estimates are 130,000 hospitalizations and more than a million ED visits per year.

Adverse drug events are caused by allergic reactions, nonallergic side effects, and unintentional overdoses—about one-third each. Of the presumably more severe effects that lead to hospitalizations, more than 50 percent are due to overdoses. About 60 percent of the overdoses are due to drugs that have narrow therapeutic indexes, such as warfarin and antidiabetic agents.

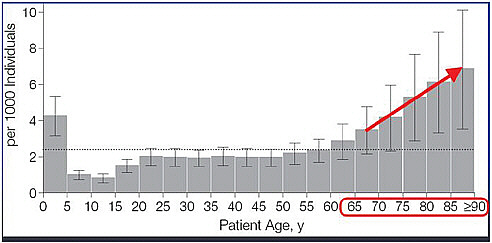

More adverse events occur in older populations (Figure 4-1). In the older adult population, 1 in 150 older adults per year will visit an ED with an adverse drug event. Among this population, the severity of adverse events is greater, resulting in seven times the hospitalization rate among adults ages 67 and older than those younger. More than half of these are unintentional overdoses, which are likely preventable. Three drugs account for one-third of these ED visits among the older population: insulin, warfarin, and digoxin.

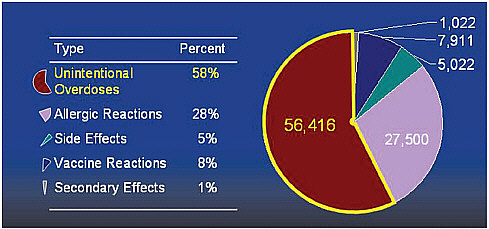

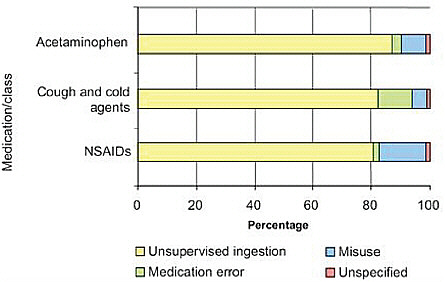

The third theme in this discussion is patient-centered prevention partnerships. The data clearly show two peaks in the incidence of ED visits for adverse drug events. The first is in children ages 0 to 5 (Figure 4-1). Unintentional overdoses accounted for 58 percent of their adverse drug events (Figure 4-2). Children at age 2 were at greatest risk for overdose (Schillie et al., 2009). About 80 percent of overdoses were due to unsupervised ingestion by children (Figure 4-3). The rest were either misuse by older children or dosing errors by parents.

CDC brought together a coalition of federal agencies, OTC manufacturers, professional organizations, and safety and health literacy experts

FIGURE 4-1 Advertise drug events treated in emergency departments by patient age, United States, 2004-2005.

SOURCE: Budnitz et al., 2006. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA 296:1858-1866. Page 1860 “Estimated Annual Incidence of Adverse Drug Events Treated in US Emergency Departments.” Copyright © 2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 4-2 Unintentional overdoses cause most emergency visits in children less than 5 years old.

SOURCE: Cohen et al., 2008.

FIGURE 4-3 Underlying causes of emergency visits for child overdoses, 2004-2005.

SOURCE: Reprinted from American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(3), Schillie, S.F. et al., Medication Overdoses Leading to Emergency Department Visits Among Children, Pages 181-187, Copyright © 2009, with permission from Elsevier.

to identify and discuss the most important issues and to determine feasibility of actions. They call it the PROTECT (Preventing Overdoses & Treatment Errors in Children Taskforce) Partnership. PROTECT focuses on two areas: (1) innovative safety packaging and (2) standardization of the volume metrics for liquid medications. Four workgroups were formed to facilitate packaging innovations, standardize dosing abbreviations, identify key messages for a national education campaign, and generate more data for key questions.

Budnitz suggested that identifying harms is key, as is focusing on the most common harm, such as older adults and anticoagulation agents. Dosing instructions need to be improved using health literacy concepts. To make a point about capitalizing on opportunities that arise, he pointed to the Tamiflu suspension problem that Wolf discussed (Budnitz et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2009). Researchers noted the problem with the dosing instructions and dosing dispenser. And the FDA and the CDC responded. But rather than pulling the product, because the problem occurred within the context of the H1N1 pandemic, the product information and dosing was corrected in a feasible manner. Budnitz ended his presentation

by calling for efforts to maximize benefit through adherence. Beyond preventing adverse outcomes, he said, it is important to watch also for literacy errors that prevent efficacious outcomes.

JOHNSON & JOHNSON INITIATIVES: MCNEIL CONSUMER HEALTHCARE

Edwin Kuffner, M.D.

McNeil Consumer Healthcare

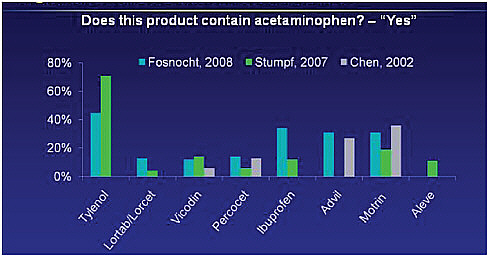

McNeil is the maker of Tylenol and the leading manufacturer of over-the-counter medicines. Important gaps exist in acetaminophen awareness. On prescription medicines, acetaminophen is often abbreviated as APAP, which is an unfamiliar term to consumers. It is time, Kuffner said, to remove APAP from prescription pharmacy labels and spell out acetaminophen, plus add an acetaminophen ingredient icon to all OTC and prescription acetaminophen-containing medicines. Acetaminophen, taken in recommended doses, is both safe and effective. But gaps in patient and consumer awareness in OTC and prescription medicines contribute to medication errors, lead to overdose, and in some cases to acute liver failure. Patients may not recognize that acetaminophen is the active ingredient in their medicines, or that it is common in many OTC and prescription medicines (Figure 4-4) (Chen et al., 2002; Fosnocht et al., 2008;

FIGURE 4-4 Variable awareness of analgesis/antipyretic ingredients in OTC and Rx products.

SOURCE: Chen et al., 2002; Fosnocht et al., 2008; Stumpf et al., 2007.

Stumpf et al., 2007). Most patients are not able to identify acetaminophen in prescription medicines labeled as APAP (Chen et al., 2002).

McNeil and the Consumer Healthcare Products Association (CHPA) along with expert advisors developed an acetaminophen ingredient icon to help patients and consumers recognize acetaminophen in multiple products and help minimize simultaneous use. They developed several graphical and design approaches for the icon and qualitatively tested them with patients in the health care setting and with consumers. A subset of patients had low health literacy. The icon evolved through each round of testing. Quantitative testing is planned for the third quarter of 2010. Testing indicated that APAP as part of the icon was confusing. An icon with text was more effective than an icon alone.

Kuffner believes that acetaminophen should be part of the FDA’s Safe Use Initiative, via partnership and collaboration with relevant stakeholders, to better manage medication risks and reduce preventable harm. Use of the icon will require a multistakeholder, comprehensive, and sustained education campaign. Take APAP off and put the icon on all medicines—prescription and OTC—that contain acetaminophen, Kuffner said.

DISCUSSION

When roundtable member Cindy Brach asked if acetaminophen should be singled out, or if there are other drugs prone to the same kind of adverse event that require the same attention, Kuffner replied that, based on the data he has seen, acetaminophen is one of the medications that should go into the Safe Use Initiative. Brach suggested that the AHRQ Centers on Education and Research in Therapeutics should be involved in any collaboration that addresses this issue.

Isham pointed out that the panel identified the following implementation steps: facilitating packaging innovations for safety, standardizing dose abbreviations for volume metric measurements, and identifying key messages for the educational campaign and data for key questions. He then asked, as automated record systems become more common within health systems for patient use in the home, are there tools that can be provided in the home so that patients can assess multiple medications? These might offer more direct opportunities for education than a national education campaign. Can we influence health care systems to develop patient-centered systems to deal with some of this complexity?

Wolf offered that his group is working through AHRQ to use electronic health records to generate plain language automatically for the top 500 prescription medications. Single pages of information on the drug are automatically generated when any new prescription is ordered. Because they are funded through AHRQ, these are publicly available. There is a

great deal of work going on to leverage electronic health record platforms to generate patient-friendly, tailored materials on medication use. The efforts attempt to include the most common omissions, that is, OTC products that patients are taking without the physician’s knowledge.

Budnitz said that he would start by focusing on common preventable harms that patients have a central role in managing. Oral anticoagulation and insulin for diabetics, for example, are drugs that cause the most acute harm and seem ripe for interventions that involve the patient and his or her literacy and how they take and use these medications.

Gerald McEvoy, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, noted that the United States is the only country in the world that uses the term acetaminophen. All other countries, including the Latin American nations, use the term paracetamol. Could that distinction be leading to patient confusion as well? Spanish-speaking consumers know the term paracetamol, but may be unfamiliar with acetaminophen.

Because very few drug benefit plans cover nonprescription products, those products are not routinely tracked via pharmacy claims data, including Part D Medicare, noted Lee Rucker from the AARP Public Policy Institute. This leads to difficulties tracking drug-related problems caused by interactions between prescription and nonprescription drugs. Health literacy comes into play because it falls to the consumer to be proactive in sharing information at every point along the dispensing and prescribing process regarding all prescription, OTC, and dietary supplements that he or she is taking. Many organizations—AARP, the FDA, the NCPIE, and others—have easily accessible medication records that consumers can fill out. But the onus is on the consumer to do it.

Angela Long, vice president of Healthcare Quality and Compendial Affairs at USP, noted that the United States Pharmacopeia-National Formulary (USP-NF) General Chapter will be posted on its website for public comment.1 She encouraged input. She offered the USP Health Literacy and Prescription Container Labeling Advisory Panel’s further assistance, suggesting that perhaps the panel could work on OTC labeling and delivery devices, a challenge brought up earlier in the session.

An additional concern raised by Wendy Mettger of Mettger Communications, relates to adult learners who don’t understand terms such as acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or even active ingredient. She asked if those terms have been tested with consumers. Parker agreed that active ingredient is a difficult term for patients. She has an upcoming study showing that consumers think that acetaminophen and antihistamine are the same thing. Research has not focused on this area. She hopes to call attention to the problem of knowing what a product is. If there is agreement that

|

1 |

See http://www.usp.org/. |

to safely use a medication, the patient needs to know what it is before he or she takes it, then knowing what a product is comes to the forefront every time safe use of a medication is addressed. Bernard Dreyer added that a lot is known about what patients with low literacy need so they can understand a label. They need pronunciation guides and simple definitions. The problem is that the real estate on all labels is very minimal. But it is the only thing that is really going to help low literacy patients understand what is on the label.

Dreyer then asked what impact USP’s General Chapters have. Are they law of the land? Does the FDA play a role? Long responded that the USP sets voluntary standards, and now the USP will work with the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy to adopt the standard. The USP will also talk with the FDA about what role it might play to get the standards taken up.

One participant asked whether patients are involved in product and standard development. Bullman used the example of the NCPIE-developed program called “Maximizing Your Role as a Teen Influencer: What You Can Do To Help Teens Prevent Prescription Drug Abuse.” The content was derived from data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and other published research. NCPIE brought together 15 organizations that were all working on the same issue but had not worked together before.2 Representatives of school health, school psychologists, parent-teacher associations, Partnership for a Drug-Free America, and American Academy of Pediatrics, for example, came together. Messaging was focus tested in two states. Now that it is launched, three states are doing an assessment of up to 500 people who have been exposed to the workshop, asking questions before, after, then at 3-month intervals. It is a fairly extensive program.

Isham ended the morning session by saying a great deal of progress can be made in the area of medication safety. For example, his health system has an ambulatory health record for its 850,000 patients and an inpatient record. The systems do not talk to each other. The doses for Coumadin, for example, do not transfer across the systems. Now a group is working on that issue. A second issue is that there is an opportunity to develop sophisticated tools to help people manage their own medications.