2

Newborn Screening as a Public Health Program

|

Important Points Highlighted by Speakers

|

BENEFITS AND PREREQUISITES OF NEWBORN SCREENING

Newborn screening programs identify children who are born with serious genetic, metabolic, hematologic, infectious, or auditory disorders (Sahai and Marsden, 2009; Wilcken and Wiley, 2008). These children generally appear normal at birth but have an inherent condition that will lead to disability or death without intervention. Screening is performed on blood samples that have been collected shortly after birth and dried on filter paper. To ensure

that the specimens can be re-evaluated if warranted by the initial screening results, extra samples are collected in the form of multiple blood spots on a standardized form. Individual states may store these extra samples for use in the quality control of current tests and the development of new tests. In addition, residual dried blood spots also have many potential uses in public health and biomedical research. (These uses are discussed in Chapter 3.)

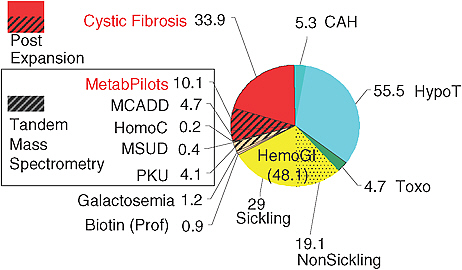

Newborn screening programs have been highly successful, said Dr. Anne Comeau, deputy director for the New England Newborn Screening Program and associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. They provide an opportunity for early identification and treatment of infants with conditions that otherwise would go unrecognized prior to irreversible damage. In New England, about 1 in 600 children is found to have one of the conditions being looked for by the screen (Figure 2-1). But newborn screening programs include much more than just a laboratory test, Comeau said. To provide parents with information and get infants into treatment, her program has pre-analytic, analytic, and post-analytic components. Every baby needs to be screened and every affected infant needs to get treatment and follow-up care.

Quality people and quality systems are essential to the success of newborn screening, Comeau said. The people running screening programs need to be well trained and competent. Quality systems need to be in place for the analysis and storage of residual dried blood spots. “It is not just the robotics of running a laboratory test,” she said.

FIGURE 2-1 The number of cases detected (169)/100,000 screened through the New England newborn screening program.

SOURCE: Comeau, 2010.

Quality programs in turn build public trust. Newborn screening programs are authorized through the legal doctrine known as parens patriae, which gives the state the right to assume certain roles of parents based on benefits to the child and to society as a whole. But such programs cannot succeed without public trust.

PRINCIPLES BEHIND NEWBORN SCREENING

There is a lot at stake in newborn screening, said Dr. Alan Fleischman, senior vice president and medical director at the March of Dimes Foundation and professor at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Extrapolating the experiences of individual states to the United States as a whole, it is estimated that more than 6,000 children are identified each year with a metabolic, endocrine, hematologic, or functional disorder (CDC, 2008). Because these tests are directly in the interest of infants, this gives states the right to mandate the tests without first obtaining informed consent from the parents, Fleischman said, although all new parents should be educated about the process. Some states allow parents to opt out of screening for various reasons, he said, although “if any form of parent consent is required, including opting out, it should be addressed only after the blood sample has been obtained.” (Issues of consent are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.)

Newborn screening programs have changed significantly in just the past five years, Fleischman said. Currently 42 states and the District of Columbia screen for 29 of the 30 recommended disorders, and all states screen for 26 or more of these disorders. New technologies have made it possible to screen for many more disorders than in the past and the number will continue to increase. This represents, Fleischman said, “a public health success story of this decade.”

Newborn screening is based on certain fundamental principles, Fleischman explained. Screening should be directed at serious diseases or disorders that significantly impair health. Conditions tested should be identifiable before symptoms appear. There need to be valid, reliable, sensitive, and specific screening methods available that can be performed shortly after birth. The benefits of early detection, including timely intervention and efficacious treatment, need to be documented. This set of requirements explains why newborn screening programs entail much more than gathering samples and testing, Fleischman said. In addition to sample collection, submission to the laboratory, and testing, the programs include the reporting of results, diagnostic confirmation, referral for treatment, long-term support of patients and families, and program evaluation.

The samples left after screening is complete have a variety of potential uses in addition to the use of residual specimens in research. The first such

use is program quality assurance and test validation. Samples are needed to ensure that tests are accurate. “It is not heartening to hear some legislators or programs in some states discarding samples after a few weeks or 30 days,” Fleischman said, since this makes it more challenging to fulfill quality assurance needs in those states.

Second, residual samples are needed to develop new screening methods. This is part of the public health program and should be seen as an essential component of the mandatory screening process, according to Fleischman.

Third, parents are increasingly requesting additional testing, particularly in the case of sudden or unexpected death. Such testing is not possible if samples have been destroyed.

Fourth, samples have the potential to be used for forensic purposes by the police, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Homeland Security, and other governmental bodies. The possibility of such use raises many difficult questions, Fleischman said.

The challenge, Fleischman said, is to balance respect for parental involvement in decisions about the storage and use of residual blood spots with the importance of the newborn screening public health program. Residual blood spots are an “incredibly important resource,” and their secondary uses, including research, should not be allowed to interfere with the public health mission of the screening itself. “The public health program is mandatory in this country. Research, though laudable, is optional.”

STAKEHOLDERS IN NEWBORN SCREENING

Many individuals and groups are stakeholders in the use of blood spots. The child is the first and most important stakeholder with regard to the screening process itself, since it is in the child’s interest to have the program. The importance to the child is why parents should not be allowed to opt out of newborn screening, Fleischman said, even if they are allowed to opt out of subsequent uses of samples.

The family is also a stakeholder in newborn screening, since the use of residual dried blood spots can have implications for the privacy and identity of family members. When parents attend meetings about the use of residual dried blood spots, Fleischman said, they often express concerns about how the use of those samples will affect not only their children but other members of the family.

Scientists and clinicians are stakeholders in the use of residual blood spots for research, because their job is to use this important resource to generate new knowledge in ways that will help all children and families. And governments and the public health departments are also similar stakeholders because they are the stewards of this important resource. Taken together, these are the primary stakeholders, Fleischman said, and each needs to have a voice in how newborn screening samples are used.