6

Strategies to Ensure Ethical Decision-Making Capacity for HIV/AIDS: Policy and Programming in Africa

|

Key Findings

|

If global donor resources remain constrained and the predicted burden of HIV/AIDS in Africa over the next decade ensues, difficult questions will inevitably arise regarding how to prioritize access to treatment ethically and equitably; the answers to these questions will have profound ethical implications. This chapter examines these ethical issues, focusing on options for building ethical decision-making capacity in Africa as a complement to the discussion of strategies to build capacity for prevention, treatment, and care in Chapter 5.

The long-term burden of HIV/AIDS will coexist with African health systems’ many other responsibilities toward the populations they serve, including overall

health system functioning, maternal and child health, prevention and treatment of infectious conditions other than HIV, injury prevention and care, mental health, and chronic conditions such as cancer and cardiovascular disease. Likewise, governments and donors have ethical obligations to address the full range of pressing global health needs, which can represent competing moral claims on limited resources. At the same time, HIV/AIDS may be exceptional in that the disease usually strikes individuals at the prime of their lives for working, having children, and supporting families. Issues of the ethical allocation of health resources between HIV/AIDS and other health needs is beyond the scope of this study. Those issues aside, however, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS is expected to increase for the forseeable future (see Chapter 2 and Appendix A). Therefore, significant resources will need to be dedicated to combating the epidemic (IOM, 2005), and this chapter addresses ethical issues regarding the utilization of those resources.

The starting point for the discussion is the expectation that needs for HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care will vastly exceed the resources available to meet those needs in resource-constrained African countries where the projected long-term burden of HIV/AIDS is very high. The combination of “high prevalence, low incomes, and heavy dependence on external assistance” in many African countries is of particular concern (Project HOPE, 2009; Haacker, 2009). Within the sphere of HIV/AIDS, many competing claims on resources will continue to arise: between subpopulations of persons who need antiretroviral treatment (e.g., in some circumstances, between those requiring their first treatment regimen and those requiring second- and third-line regimens); between subpopulations of persons who need preventive interventions; and among efforts to provide ART, HIV/AIDS care, and preventive interventions (see Chapter 2 for a discussion of these trade-offs). Such trade-offs are and will continue to be a reality, and the ways in which policy makers and others weigh them and their consequences are at the heart of this ethical inquiry. Whatever the outcome of the decisions made regarding the allocation of resources in the context of HIV/AIDS in Africa, those decisions will make an enormous difference in the lives of large numbers of people living with HIV/AIDS.

This chapter first reviews existing principles for ethical decisions in health care that have been promulgated by international organizations. The subsequent section examines how an ethical decision-making capacity for HIV/AIDS policy and programming can be developed in Africa.

EXISTING PRINCIPLES FOR ETHICAL DECISIONS IN HEALTH CARE

This section examines in turn the levels of decision making in the allocation of health resources; key moral imperatives; the concept of equal moral status; and international covenants, codes, and declarations on ethics.

Levels of Decision Making in the Allocation of Health Resources

The World Medical Association’s (WMA’s) Medical Ethics Manual identifies three levels of decision making for the allocation of health resources (Williams, 2009). Important ethical responsibilities exist at all three levels because decisions at each level are based on values and have significant consequences for the health and well-being of individuals and communities (Williams, 2009). At the macro level, governments determine the overall health budget and its distribution across such categories as human resources, hospital operating expenses, research, and disease-specific treatment programs (Williams, 2009). Given the projected increase in workload associated with managing the HIV/AIDS epidemic, for example, governments must make decisions at this macro level to ensure an adequate and competent workforce (see the discussion of optimizing the existing workforce in Chapter 5). Additionally, policy makers must consider competing societal goods, such as transportation, education, energy, and employment, especially since multiple socioeconomic determinants have powerful effects on the health of individuals and populations. At the meso level, institutions such as ministries of health, hospitals, and clinics determine which services they will provide and how much they will spend on such expenses as staff, equipment, and supplies (Williams, 2009). At the micro level, health care providers decide what expenditures to recommend for the benefit of each individual patient, such as tests, referrals, hospitalization, and generic versus brand-name pharmaceuticals (Williams, 2009).

Key Moral Imperatives

The committee identified two key imperatives it believes should guide ethical decision making: (1) at the macro and meso levels, to pursue justice in the distribution of benefits and burdens; and (2) at the micro level, to ensure that decisions are in the best interests of patients.

Ethical decisions at the macro and meso levels should equitably protect the interests of everyone who stands to lose or gain from those decisions. At their gravest, decisions on resource allocation can deny life-saving prevention or treatment to patients in need. A morally acceptable approach to trade-offs in rationing scarce health care resources should satisfy the following conditions (Purtillo, 1999):

-

There should be a demonstrable need that the trade-off is necessary; the burden of proof is on those who propose the trade-off.

-

There should be no choice other than the trade-off.

-

All affected individuals should participate in the decision-making process, either directly or through the representatives of groups.

-

Beneficial services withheld should be proportional to the actual scarcity that exists.

This approach to trade-offs is consistent with African community-oriented ethical outlooks in which the individual is understood to be embedded in a web of social relationships and interdependence (Gyekye, 1997). When considering trade-offs in the context of endemic disease and public health needs, African countries face serious dilemmas. African community-focused, “common good” standards of ethics may influence and inform trade-off decisions. As societies differ in the degree of ethical importance they place on either individual interests or the common good and the interests of communities, a range of value systems must be respected and understood.

The micro-level imperative is grounded in international standards for the practice of medicine, including the physician’s duty to “act in the patient’s best interest when providing medical care” (WMA, 2006, Duties of Physicians to Patients). Even at the micro level, resource allocation trade-offs sometimes occur between individual patients, in which case an additional ethical responsibility for fairness arises. According to the WMA’s Declaration on the Rights of the Patient, in “circumstances where a choice must be made between potential patients for a particular treatment that is in limited supply, all such patients are entitled to a fair selection procedure for that treatment. That choice must be based on medical criteria and made without discrimination” (Williams et al., 2009, p. 70; WMA, 2005, Principle E). The moral basis for requiring fair procedure extends to the requirement for justice at the meso and macro levels, where the access of individuals, communities, and populations to potentially life-saving HIV/AIDS services is subject to the decisions of public officials and other institutional actors.

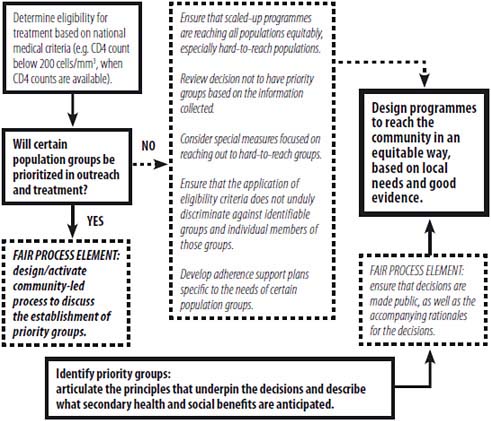

At any of the three levels of decision making, when people whose needs exceed available resources have approximately the same clinical status or risk exposure, medical criteria alone are insufficient to guide resource allocation decisions, as will often be the case with needs for HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care. In these situations, compliance with the WMA’s directive that choices must be based on medical criteria and made without discrimination (Williams, 2009; WMA, 2005) is necessary but not sufficient to reach an ethically sound decision. Donors, national laws, ministries of health, local health departments, managers, hospital ethics committees where they exist, and health care professionals all make resource allocation decisions using a variety of additional criteria. The criteria in use may be explicit, as are those of some governments, or may be implicit in the choices practitioners make. Decisions governed by implicit criteria can be arbitrary, often leading to inequity and inefficiency (Rosen et al., 2005). This is one of the reasons why, from a moral point of view, the process of decision making for resource allocation must incorporate robust safeguards not only against discrimination, but also against arbitrary or self-serving exercises of power (see Figure 6-1 for Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS] guidance on ethical and equitable provision of treatment). This issue is addressed further below in the discussion of procedural justice.

FIGURE 6-1 Roadmap for ethical and equitable provision of treatment.

NOTE: The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) updated 2010 guidelines recommend eligibility for treatment at a CD4 count of 350 cells/μL.

SOURCE: UNAIDS/WHO, 2004.

Equal Moral Status

Respect for individuals’ equal moral status requires fair decision making even in the face of scarcity. Each patient has an equal claim to fair decision-making procedures on the part of physicians, and each member of society has an equal claim to just treatment by institutions and the state. Equal moral status is recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR): “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (UN, 1948).

Policy makers do not necessarily violate the principle of equal moral status by selecting certain groups—such as health workers or mothers of young children—for priority on the grounds of their expected contributions to society. However, priorities must be established through a fair process that (1) includes all stakeholders; (2) is publicly transparent, enforceable, and revisable; and (3) is founded

in relevant evidence, reasons, and ethical values (Daniels, 2004; Macklin, 2004; UNAIDS/WHO, 2004).

Unfortunately, regard for the equal moral status of individuals is far from universally practiced. In many societies, for example—whether in low-, middle-, or high-income countries—women and girls are assigned second-class status in the distribution of social goods such as employment, health, education, nutrition, and protection from violence. In some societies, groups such as men who have sex with men, transgender persons, commercial sex workers, and injecting drug users suffer stigma and discrimination that threaten their rights and well-being and impede their access to HIV/AIDS services. Because the key moral imperatives identified by the committee presuppose the equal moral status of individuals, the committee’s recommendations for building ethical decision-making capacity reflect the importance of upholding this value under challenging circumstances.

International Covenants, Codes, and Declarations on Ethics

A variety of organizations in the international community have promulgated principles for ethical decision making in health care. International covenants, codes, and declarations that bind member states to respect, promote, and realize human rights are in abundance. The UDHR affirms that everyone “has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well being of himself and his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services” (UN, 1948). The responsibilities of governments in realizing the right to health were made more specific in 1966, 20 years after the adoption of the UDHR, with the promulgation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESR),1 which requires governments that ratify the agreement to, among other things:

-

provide for reduction of the stillbirth rate and infant mortality and for children’s healthy development;

-

prevent, treat, and control epidemic, endemic, occupational, and other diseases;

-

create conditions that will ensure medical attention and services to all when needed;

-

provide those who lack sufficient means with the necessary health care facilities;

-

establish prevention and education programs;

-

promote the social determinants of good health; and

-

adopt appropriate legislative, administrative, budgetary, judicial, promotional, and other measures toward the full realization of the right to health (UN, 1966).

The contours of the right to health have been richly developed by the United Nations (UN) Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in General Comment No. 14 and the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health appointed by the UN General Assembly (Gostin, 2009; UN Economic and Social Council, 2000, 2004, 2005), and in the context of children and HIV/AIDS in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, 2003).2

The call from international bodies targets not just individual member states but also the global community. In June 2001, the UN General Assembly, in its Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS—“Global Crisis—Global Action”—called for enhanced coordination and intensification of national, regional, and international efforts to combat the pandemic in a comprehensive manner. The General Assembly stressed strong leadership at all levels of society, including government, as essential for an effective response. In particular, there was to be agreement on canceling all bilateral official debts of those members belonging to the Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) Initiative in return for “demonstrable commitment by them to poverty eradication” (UN, 2001).

In the World Summit Outcome of October 24, 2005, the UN General Assembly called again for stronger leadership on HIV/AIDS and for the scaling up of a comprehensive response. It committed to providing coherent support for the programs devised by African leaders; to encouraging pharmaceutical companies to make drugs, including antiretroviral drugs, affordable and accessible in Africa; and to ensuring increased bilateral and multilateral assistance on a grant basis to combat infectious diseases in Africa through the strengthening of health systems (UN, 2005).

Clearly the global community has amply demonstrated its commitment to combating the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa. The dire state of health care and the failing health systems in many African countries, however, raise questions about whether the aid provided has been effective and how much African leaders have done to help their own societies.

The African Union, the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) are some of the organizations within Africa that have responded to the epidemic and to Africa’s commitment to action in accordance with national and international responsibilities. In the Lome Declaration on HIV/AIDS in Africa (OAU, 2000), the Assembly of Heads of States and Governments of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) underscored the importance of health sector reform, with a focus on epidemics such as HIV/AIDS (OAU, 2000). The same group in April 2001 passed the Abuja Declaration on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Other Related Infectious Diseases, declaring AIDS on the continent a state of emergency, with countries pledging that at least 15 percent of annual budgets would be devoted to health sector improvements (OAU, 2001). To date, however, most countries have

barely reached 6 percent. In 2003, the Maputo Declaration pledged similar obligations, and in 2008, the African Parliament Union resolved to promote health in Africa by combating HIV/AIDS and improving maternal and child health (African Union, 2003). Leaders once again stressed the importance of strengthening national health systems and the fact that HIV/AIDS cannot be separated from the struggle against poverty.

African leaders appear to understand what is required. Why then is the state of health and the delivery of health care in the region in such dire decline? Is it because Africa lacks the requisite capacity, or is it because African leaders fail to deliver on their promises for improved health services? Most likely, both of these reasons apply. What is required is a global, regional, and national commitment: global leaders need to display commitment to the international codes and guidelines to which they have already agreed, and Africa needs to honor its commitment to codes and declarations that countries have ratified. Some successes have, however, been achieved with respect to the fulfillment of global, regional, and national commitments to health-related ethical responsibilities. Two examples are highlighted below.

The first is the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), which forms partnerships with some of the world’s poorest countries, but only those committed to good governance, economic freedom, and investments in their citizens. MCC provides these countries with large-scale grants to fund country-led solutions for reducing poverty through sustainable economic growth. MCC grants complement other U.S. and international development programs. Countries in Africa that are viewed as well-performing and have therefore been funded by MCC include Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, São Tomé and Principe, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. Despite each MCC partner country’s already having democratic institutions, MCC’s approach is to create incentives for reforms within the country while at the same time respecting existing processes and democratic actors. Partner countries must demonstrate a commitment to accountable and democratic governance. Indicators of democratic standing used by MCC include respect for political rights, civil liberties, voice, and accountability. Governments that score well are rewarded with resources for poverty reduction and economic growth programs. Partner countries are required to:

-

Maintain meaningful, public consultative processes throughout the development and implementation of their programs. Hence, society at large (civic, private, and political sectors) is involved in setting priorities for the country’s development. Moreover, elected officials are empowered to exercise their representative rights and responsibilities.

-

Adhere to domestic legal requirements, which encompasses ratifying the programs; informing government bodies, including the legislature, as

-

appropriate; and reflecting funds received in the national budget. Adhering to these requirements allows for debates on the content of the programs at various levels, including government, resulting in firmer political commitment. In addition, the legislature’s role as the democratic locus for political debates and decision making is reaffirmed.

-

Employ transparent processes for program implementation, including processes for procurement by implementing agencies, reporting, and outreach activities. Domestic accountability is strengthened in this manner.

The MCC approach, by emphasizing transparency and responsibility for implementation in all sectors of society, supports country ownership and accountability. Successful MCC programs in Africa show that where donors demonstrate a firm commitment to promoting capacity, sustainability, and government commitment, positive results can be achieved and the creation of dependency on donors and entitlements circumvented (Mandaville, 2007).

A second example of fulfillment of commitments to health-related ethical responsibilities is captured in UNAIDS’ December 2009 “Update on the Impact of the Economic Crisis,” contained in its report on HIV prevention and treatment programs. UNAIDS found that governments are already taking actions to sustain HIV/AIDS responses. These actions include:

-

trying to mobilize additional funding by pursuing advocacy with development partners, developing a national trust fund or solidarity fund for HIV/AIDS, and exploring greater use of user fees and/or health insurance to pay for ART;

-

cutting budgets and expenditures and/or rationalizing interventions and reducing inefficiencies by seeking technical efficiencies in the HIV/AIDS response, merging agencies or other institutional reforms to reduce costs, cutting spending in areas deemed unnecessary or ineffective and imposing stricter rules on operational spending, creating a centralized national procurement system for antiretroviral drugs and prevention commodities and improving drug supply chain management, and strengthening fiduciary systems; and

-

rethinking strategic plans by integrating HIV/AIDS into broader national planning, developing a strategy for the health system that takes account of the impact of the crisis, and revising existing national AIDS strategies and annual action plans and their costs to reflect the impact of the crisis.

In addition, many countries expressed a need for external technical assistance to help face the current crisis in a number of areas, including taking steps to improve resource allocation and the efficiency of interventions, prioritizing programs in the context of scarce resources, analyzing the cost/benefits of interventions, and

defining efficient intervention packages for the most at-risk groups (UNAIDS, 2009).

African governments should be encouraged to adopt and apply the internationally established principles for ethical decision making in the HIV/AIDS context described above. The challenge ahead is how African health professionals, institutional leaders, and civil society can take responsibility for ethical decision making in the face of poor governance, corruption, military rule, armed conflict, civil unrest, dictatorship, and other adversities. The following section explores strategies for ensuring ethical decision-making capacity for HIV/AIDS policy and programming in Africa.

BUILDING ETHICAL DECISION-MAKING CAPACITY FOR HIV/AIDS POLICY AND PROGRAMMING IN AFRICA

Experience with and understanding of local conditions are essential components of ethical decision-making capacity. Ministries of health, national AIDS councils, and other authorities in African countries hard hit by HIV/AIDS have already had to make decisions under severely challenging circumstances for years. What lessons have they learned from this experience, and what can be done to document and disseminate these lessons? The following discussion should be considered alongside the existing base of decision-making experience in Africa. Key areas of inquiry include procedural justice in specific African contexts; which responsible parties are involved in decision-making processes and what capacities they require for ethically informed decisions; capacity building to support ethical decision making; programs in ethics and human rights currently offered in Africa; an “all-of-government” approach to health in the form of interministerial committees; and the inclusion of socially disadvantaged groups in HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care efforts.

Procedural Justice in Specific African Contexts

The principle of the equal moral status of individuals requires that policy makers avoid arbitrary or capricious distinctions that discriminate against individuals and groups. Trade-offs in resource allocation can be understood as problems of distributive justice, defined as “fair, equitable, and appropriate distribution determined by justified norms that structure the terms of social cooperation” (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009, p. 226). Distributive justice has two complementary aspects: substantive justice and procedural justice.

Substantive justice deals with the content of allocation decisions, ensuring fair distribution of scarce resources. It requires fairness in allocating benefits and burdens in society. Procedural justice deals with fairness in the process of decision making. A focus on procedural justice is helpful especially when there is no reasonable prospect of consensus on substantive principles to guide resource

allocation, as is likely to be the case in the trade-offs involved in HIV/AIDS-related decision making in resource-constrained African countries.

Norman Daniels’ Accountability for Reasonableness (A4R) framework identifies four necessary conditions for procedural justice (Daniels, 2008):

-

Publicity condition—decisions and rationales are publicly accessible.

-

Relevance condition—rationales appeal to evidence, reasons, and principles accepted as relevant by fair-minded stakeholders.

-

Revision and appeals condition—mechanisms and opportunities exist to challenge decisions, resolve disputes, and revise and improve policies in light of new evidence or arguments.

-

Regulative condition—decision-making processes are regulated, either voluntarily or publicly, to enforce the above three conditions.

For example, A4R in “patient and site selection in the global effort to scale up ARTs for HIV/AIDS in low-income, high-prevalence countries” focuses on four issues: cost recovery for ART, medical eligibility criteria, siting of treatment facilities, and priority to special groups (Daniels, 2008, pp. 274–292). More broadly, Daniels and colleagues have developed an evidence-based policy tool called Benchmarks of Fairness for analyzing the effects of health policies on equity, efficiency, and accountability in developing countries, which has been tested in Cameroon, Ecuador, Guatemala, Thailand, and Zambia (Daniels, 2006; Daniels et al., 2000, 2005).

Youngkong and colleagues reviewed 18 empirical studies of priority setting for health interventions in developing countries, including South Africa, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Uganda (Youngkong et al., 2009). Several of these studies employed the A4R model, but other models were also used:

-

Lasry and colleagues (2008) describe a “decision support system” specifically aimed at local government agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), or public health institutions currently offering HIV/AIDS programs in a low-income community and illustrate its use in the context of the KwaDukuza Primary Health Care Clinic near Durban, South Africa. Kapiriri and Martin (2010) propose a framework, derived partly from qualitative research, to support practical planning and evaluation of priority-setting efforts in low- and middle-income countries.

-

Kapiriri and Martin (2007) argue that to improve priority setting, it is necessary to describe current practices (while remaining aware that they are “value laden and political”) and to identify the institutions and groups that have legitimacy (i.e., moral authority) so they can be empowered through training, access to tools and evidence, and legal mandates.

The achievement of procedural justice in practice depends not only on the use of a fair decision-making process but also on the secure existence of supportive political and legal institutions. These institutions are characterized below in terms of three “mandates” of procedural justice.

Mandate 1:

An Informed Civil Society

According to UNAIDS, civil society speaks with many voices and represents many different perspectives (UNAIDS, 2010). Civil society is broadly defined to include HIV/AIDS service organizations; groups of people living with HIV/AIDS; youth organizations; women’s organizations; businesses; trade unions; professional and scientific organizations; sports organizations; international development NGOs; and a broad spectrum of religions and faith-based organizations, both global and at the country level.

Given the diversity of civil society organizations (CSOs) within the health sector, it is not surprising that, at times, these CSOs represent competing interests as well as competitors for funding, human resources, and other important assets. While competition is of obvious value in promoting institutional performance, it also tends to discourage collaboration and risks undue duplication or dispersion of efforts (Advisory Group on Civil Society and Aid Effectiveness, 2007). Despite these potential drawbacks, CSOs can and have mobilized, empowered, and supported community responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. For this reason, UNAIDS and others have identified civil society as playing key roles in the response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in countries around the world.

For CSOs to be successful, they must be fully engaged in decision-making processes. They must have access to full information and to decision-making processes, as well as the right to challenge the decisions that are made. An example is the Treatment Action Campaign, formed in 1998 in South Africa. Its purpose is to challenge unjust decisions concerning the allocation of health resources through the civil society sector. Most well known is a successful constitutional challenge before the South African Constitutional Court, which required the government to grant greater access to treatment for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (Heywood, 2003).

If procedural justice in developing countries depends upon the accountability of civil society, what then does civil society depend upon? Civil society cannot sustain itself without serious long-term funding strategies, such as those called for in the recommendations at the end of this chapter. The desired capabilities of African CSOs are not expected to be in place today, but to be built over the next decade. When the need arises to ration or fairly distribute a scarce medical resource such as ART, the lack of procedural justice can lead to chaos. Therefore, a systematic process for procedural justice is needed. Long-term procedural justice and accountability in African countries with high HIV/AIDS burdens and

few resources, as in all countries, will depend upon civil society and its ability to hold governments accountable.

Mandate 2:

Legal Capacity and Capability

The second mandate of procedural justice is legal capacity and capability. If decisions made are unethical and unfair, civil society must be able to challenge them. To this end, countries must follow the rule of law; operate honestly and transparently; and welcome the input of a diverse, well-informed community. Without the rule of law, particularly law incorporating the framework of human rights, it is difficult to achieve procedural justice (Heywood, 2010).

In another illustration from South Africa, civil society fought long for a new constitution that included social and economic rights. The South African constitution states that everyone has a right to access to health care services, and that the state must take reasonable legislative and other measures to progressively realize the right to access to health care services (Heywood, 2010).

Mandate 3:

Shared Governance

Globally, institutions of shared governance are organizations that sit together and take responsibility for decision making around resource allocation. Although these institutions do exist, this does not mean that government abdicates responsibility. In the case of global funding for HIV/AIDS programs, NGOs and CSOs, international organizations, and national governments should all be involved in the decision-making process (Heywood, 2010).

National AIDS councils, prevalent in many African countries, illustrate shared governance. These councils often encompass a range of stakeholders including public officials, professional organizations, and NGOs. They have a variety of powers, either binding or advisory (Heywood, 2010).

Responsible Parties and Required Capacities

Taking a long-term perspective on the pursuit of procedural justice is warranted in light of the complex political and institutional components of real-world priority setting. Who is exerting influence, who ought to be exerting influence, and what practical steps can be taken to bring the two more into line? Time will be required to build an accurate understanding of the influences at work in particular decision-making contexts across many different countries and localities where resource streams are of varying origins, levels, and degrees of predictability, and where the HIV/AIDS epidemic takes different forms and has different impacts.

Meanwhile, it is possible to identify and empower stakeholders in particular settings who should have more influence than they actually do. For example, when a sample of health workers in Uganda was asked to rank actors by actual

versus ideal influence on priority setting, respondents identified patients and the general public as those who should have more influence than they actually do, as compared with donors and politicians, whom respondents viewed as having excessive influence (Kapiriri et al., 2004). A parallel, alternative approach is to identify relatively enduring processes through which resource allocation decisions are actually made and to enhance the ethical capacity (relative to HIV/AIDS policy and programming) of already-empowered actors. The range of such actors might include local health service providers, local health system managers, HIV/AIDS program implementers, civil society (community-based organizations and NGOs), traditional leaders, local public officials, academic institutions, national public officials, regional organizations, and the media (to promote responsible and balanced reporting of information in support of participatory democracy).

Some countries have already developed approaches to ethical decision making in the face of scarce resources, both fiscal and human. In Cameroon, for example, a physician’s choice of a treatment protocol must be submitted to a therapeutics committee for discussion and approval. A weekly or bimonthly meeting is held with all relevant personnel, including physicians, paramedics, social workers, and possibly community relay agents, to discuss, revise, or approve the protocol. The members of the therapeutics committee receive training prior to their service (Eboko et al., 2010). At the community level, governments should consider creating multidisciplinary treatment and care committees, similar to those in Cameroon, to guide practitioner-driven decisions. These committees would carefully review, modify, and approve treatment and care protocols for persons with HIV/AIDS.

Capacity Building to Support Ethical Decision Making

Several key questions arise regarding capacity building for institutions, groups, and individuals to support effective leadership and participation in the sorts of decision-making processes that would help realize conditions of procedural justice. First, to what extent, and for whom, is formal training in ethics required? Training would be valuable both to meet immediate needs and to contribute to long-term capacity building. What are the options for providing such training? How should curricula be designed? How can culturally and historically relevant content be developed? Possibilities include ethics courses or modules in degree programs for nursing, medicine, public health, government, management, and media, as well as ethics components in continuing education programs for active professionals. To address these issues, partnerships among academic institutions, government, and professional organizations should be explored. Second, it is possible to identify a set of core competencies integrating all the factors relevant to sound decision making—not only ethics but also budgeting and management, evidence assessment, health policy analysis, and communications. Assuming it would be rare and costly for any one person to master all of the req-

uisite competencies, what can organizations do to distribute areas of competency across personnel teams? Third, what inputs are needed to support sound decision making—such as interpretations of scientific evidence, or data for program monitoring and evaluation—and how can they be supplied in a regular and timely manner? Fourth, how can ethical and evidential considerations be effectively communicated, as needed, among local, district, national, and regional decision makers? Fifth, to the extent that resources come from foreign donors, how can institutions be constructed to gain donors’ trust so that donors will be willing to relinquish some control over resource allocation decisions?

Programs in Ethics and Human Rights Currently Offered in Africa

An extensive literature search reveals that while several programs within and outside of educational institutions include ethics and/or human rights, they are directed mainly at ethics of health-related research. Funders of ethics activities in Africa include the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Wellcome Trust, the Fogarty Center, and the European Union. UNESCO has developed an extensive database of ethics teaching programs on the continent. At the postgraduate level, only three African institutions have developed capacity-building programs in ethics and human rights that do not focus mainly on research.3 At the undergraduate level, the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) has developed a core curriculum in bioethics, human rights, and health law that is integrated into health sciences curricula. The following core competencies are required by HPCSA to qualify health care practitioners:

-

Show respect for patients and colleagues without prejudice, with an understanding and an appreciation of their diversities of background and opportunity, language, and culture.

-

Strive to improve patient care, reduce inequalities in health care delivery, and optimize the use of health care resources in our society.

-

Use his or her professional capabilities to contribute to the community as well as to individual patient welfare.

-

Demonstrate awareness, through action or in writing, of the legal and ethical responsibilities involved in individual patient care and the provision of care to populations.

-

Consider the impact of health care on the environment and the impact of the environment on health (The Committee on Human Rights Ethics and Professional Practice, 2006, p. 5).

It is important that students be exposed to critical thinking and ethical analysis and reasoning and provided with pertinent resources to develop these skills as early in their training as possible. These skills can then be used to develop professionalism that will help students be prepared when they eventually face complex decisions in a range of situations, from the patient’s bedside to policy-level decision making in the health ministry.

Finally, while it is important to develop programs that extend beyond research ethics, it is necessary to bear in mind that the HIV/AIDS epidemic has rendered Africa fertile ground for the global proliferation of clinical research, including multicenter, international, and pharmaceutical studies. Research must continue to serve the health needs of the continent. It must always be ethical, protecting the rights and well-being of participants. Research participants are often vulnerable, burdened by multiple health conditions, poverty, illiteracy, and lack of full access to health care. These conditions, together with the several examples of exploitation to which the continent has been subjected, underscore the importance of maintaining high ethical standards. Currently, the research ethics committee (REC) process serves this protective function. If this function is to be carried out with commitment, however, it will incur financial costs, and funders, including PEPFAR and the Global Fund, must consider developing ethics capacities in this arena.

While most countries in Africa use international benchmarks for their research participant programs, capacity to implement these benchmarks varies among RECs within and among countries. Programs should be developed to address these shortfalls, together with monitoring and evaluation. National and regional RECs, for example, could be constituted to address these concerns.

Interministerial Committees

A comprehensive approach to the management of HIV/AIDS will include ensuring the basic survival needs of the people in a country, thereby addressing the delivery of some of the social determinants of health (Gostin, 2007, 2008). Health cannot be achieved if it is viewed as a silo, with the only responsible and accountable people being ministers of health and their designees. Some of the fundamental requisites for meeting basic survival needs are well-functioning health systems, essential medicines and vaccines, clean air, clean water, diet and nutrition, sanitation, sewage, and pest control, which can go a long way toward alleviating poverty. However, social, economic, cultural, and behavioral determinants (e.g., living and working conditions, mental health, spiritual well-being, physical environment, personal health practices, capacity, culture, and discriminatory practices) impact health (WHO, 1986). Also required, therefore, is a broader view of health needs based on social determinants that incorporates psychosocial and justice issues. Access to health facilities is necessary as well, in turn requiring attention to adequate transport. Finally, health is influenced substantially

by choices people make about how to live their lives. For these choices to be well informed, people must have access to education and information.

Accordingly, in the committee’s judgment, building ethical decision-making capacity requires multisectoral and multidisciplinary collaboration. National governments should consider incorporating professionals with training in ethics into interministerial committees that address all issues affecting the public’s health, analogous to the South African Ministerial Council on Innovation now being considered.

Inclusion of Socially Disadvantaged Groups in HIV/ AIDS Prevention, Treatment, and Care Efforts

Criminalization of same-sex behavior in certain African countries and its adverse impacts on efforts to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic are of serious concern. The committee welcomes efforts to counteract the criminalization movement, such as the new United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)/UNAIDS Global Commission on HIV and the Law.

The committee raises this issue both as a component of procedural justice and as a concern in its own right. In some countries, the epidemic is concentrated among groups whose behavior is criminalized or stigmatized, such as men who have sex with men, commercial sex workers, and injecting drug users. Members of these groups are at heightened risk of exposure to HIV infection. Moreover, preventive interventions could be delivered to them very cost-effectively (Hecht et al., 2009). Yet political will to reach out to these individuals with preventive services is often lacking among both governments and donors, and some governments are actively hostile to these groups. What are some viable options for representing their interests fairly in decision making about HIV/AIDS policy and programming? Similar questions apply to girls and women who lack the means to negotiate safe sex. In general, the political constituency for preventive services is meager. How can the political will to pursue prevention efforts be strengthened in accordance with the evidentially demonstrable need for them? How can the broader public health impact of adequate preventive measures be appreciated, perhaps from the viewpoint of enlightened self-interest among members of society at large, without scapegoating groups already suffering from a concentrated epidemic?

While socially disadvantaged groups are particularly vulnerable, so, too, are children, particularly girls, who have lost one or both parents and have little support, most of whom have to stop going to school (Case et al., 2004). They are placed on a usually irreversible downward trajectory that can include transactional sex and a high risk of HIV/AIDS. Much has been written about AIDS orphans, and PEPFAR focuses on this group. However, the needs of children made vulnerable by HIV/AIDS will continue to grow, requiring special attention in ethical decision making relating to their health, education, and well-being. Pre-

vention efforts targeting children have the potential for long-term positive effects. Ethical guidance is needed to ensure that all vulnerable children are reached, not just those already affected by HIV/AIDS.4

The ethical imperative of equal moral status of individuals and the mandates of procedural justice are largely being ignored with regard to socially disadvantaged groups and vulnerable children. Major opportunities for prevention are also missed, as these groups are less likely than others to access HIV/AIDS services. The UNAIDS International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights (see Annex 6-1) delineate the necessary capacities for states to protect these groups and offer a legal framework for their protection, including antidiscrimination laws. However, many countries do not comply with these guidelines.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee concludes that many key decision makers in Africa need assistance in developing the capacity for ethical decision making with respect to policies, programs, and resource allocation for HIV/AIDS in their populations. Core competencies for ethical decision making need to be defined in such areas as budgeting, management, evidence assessment, communications, and health policy analysis. Insufficient capacity exists to deal with counterethical pressures from powerful actors. In many cases, government officials also need assistance in developing accountability and competence for their decisions, particularly with reference to priority setting and fair allocation of scarce resources. Therefore, the committee offers the following recommendations.

Recommendation 6-1: Enable and reinforce capacity for ethical decision making. Donors and governments should help build capacity for ethical decision making by adequately funding education and training in the disciplines of ethics, human rights, and pertinent aspects of the law. This training should include both educational and implementation components.

Recommendation 6-2: Donors and governments should support civil society organizations where they exist and help develop them in other places over time. As a first step, the focus should be on procedural justice. Therefore, U.S. government agencies, including the State Department, USAID, and the Department of Health and Human Services, should provide technical and financial support to recipients of their health assistance for the establishment of effective mechanisms for procedural justice, including transparency, accountability, and responsibility.

Recommendation 6-3: Professionals with training in ethics should be incorporated into multisectoral teams. To increase the capacity for ethical decision making at the national level, professionals with training in ethics should be incorporated into national government multisectoral teams that include ministries of health, finance, and education, as well as other government ministries whose work is relevant to HIV/AIDS; civil society organizations; educational institutions; professional organizations; and nongovernmental organizations.

REFERENCES

Advisory Group on Civil Society and Aid Effectiveness. 2007. Civil society and aid effectiveness: Issues paper. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/59/11/39499142.pdf (accessed November 1, 2010).

African Union. 2003. Maputo declaration on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and other related infectious diseases. http://www.africa-union.org/root/AU/Conferences/Past/2006/March/SA/Mar6/Maputo_Declaration_HIV-AIDSTB.pdf (accessed August 10, 2010).

Beauchamp, T. L., and J. S. Childress. 2009. Principles of biomedical ethics, 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Case, A., C. Paxson, and J. Ableidinger. 2004. Orphans in Africa: Parental death, poverty, and school enrollment. Demography 41(3):483-508.

The Committee on Human Rights Ethics and Professional Practice. 2006. Core curriculum on human rights, ethics and medical law for health care practitioners. Pretoria: Health Professions Council of South Africa.

Daniels, N. 2004. How to achieve fair distribution of ARTs in 3 by 5: Fair process and legitimacy in patient selection. Geneva: WHO.

———. 2006. Toward ethical review of health system transformations. American Journal of Public Health 96(3):447-451.

———. 2008. Just health: Meeting health needs fairly. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Daniels, N., J. Bryant, R. A. Castano, O. G. Dantes, K. S. Khan, and S. Pannarunothai. 2000. Benchmarks of fairness for health care reform: A policy tool for developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(6):740-750.

Daniels, N., W. Flores, S. Pannarunothai, P. N. Ndumbe, J. H. Bryant, T. J. Ngulube, and Y. K. Wang. 2005. An evidence-based approach to benchmarking the fairness of health-sector reform in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83(7):534-540.

Eboko, F., C. Abé, and C. Laurent. 2010. Accès décentralisé au traitement du VIH/sida: Évaluation de l’expérience camerounaise. Agence Nationale de recerches: sur le sida et les hipatites virales. Paris: ANRS.

Gostin, L. O. 2007. Meeting the survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: A proposed model for global health governance. Journal of the American Medical Association 298(2):225-228.

———. 2008. Meeting basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: Toward a framework convention on global health. Georgetown Law Journal 96(2):331-392.

———. 2009. Public health law: Power, duty, restraint, 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gyekye, K. 1997. Tradition and modernity: Philosophical reflections on the African experience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Haacker, M. 2009. Financing HIV/AIDS programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Affairs 28(6): 1606-1616.

Hecht, R., L. Bollinger, J. Stover, W. McGreevey, F. Muhib, C. E. Madavo, and D. de Ferranti. 2009. Critical choices in financing the response to the global HIV/AIDS pandemic. Health Affairs 28(6):1591-1605.

Heywood, M. 2003. Preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission in South Africa: Background, strategies and outcomes of the Treatment Action Campaign’s case against the Minister of Health. South African Journal on Human Rights 19(2):38.

———. 2010. Presentation to the IOM committee on envisioning a strategy to prepare for the long-term burden of HIV/AIDS: African needs and U.S. interests. Pretoria, South Africa, April 12, 2010.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2005. Scaling up treatment for the global AIDS pandemic: Challenges and opportunities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2007. PEPFAR implementation: Progress and promise. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2010. Strategic approach to the evaluation of programs implemented under the Tom Lantos and Henry J. Hyde U.S. Global Leadership against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Reauthorization Act of 2008. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kapiriri, L., T. Arnesen, and O. F. Norheim. 2004. Is cost-effectiveness analysis preferred to severity of disease as the main guiding principle in priority setting in resource poor settings? The case of Uganda. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 2.

Kapiriri, L., and D. K. Martin. 2007. A strategy to improve priority setting in developing countries. Health Care Analysis 15(3):159-167.

———. 2010. Successful priority setting in low and middle income countries: A framework for evaluation. Health Care Analysis 18:129-147.

Lasry, A., M. Carter, and G. Zaric. 2008. S4HARA: System for HIV/AIDS resource allocation. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 6(1):7.

Macklin, R. 2004. Ethics and equity in access to HIV treatment: 3 by 5 initiative. Geneva: WHO.

Mandaville, A. 2007. MCC and the long term goal of deepening democracy. Washington, DC: Millennium Challenge Corporation.

Organisation of African Unity (OAU). 2000. Lome declaration: Declarations of the decisions adopted by the thirty-sixth ordinary session of the assembly of heads of state and government. In AHG/ Decl. 1 (XXXVI). Lome, Togo.

———. 2001. Abuja declaration on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and other related diseases. Abuja, Nigeria.

Project HOPE. 2009. The difficult but necessary choices in fighting HIV/AIDS. Health Affairs 28(6):1575-1577.

Purtillo, R. 1999. Distributive justice: Clinical sources of claims for health care. In Ethical dimensions for the health professions, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Company. Pp. 251-266.

Rosen, S., I. Sanne, A. Collier, and J. L. Simon. 2005. Hard choices: Rationing antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in Africa. The Lancet 365(9456):354-356.

UN (United Nations). 1948. Universal declaration of human rights. Paper read at general assembly of the United Nations. http://www.eduhi.at/dl/Universal_Declaration_of_Human_Rights.pdf (accessed November 1, 2010).

———. 1966. International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. Paper read at general assembly of the United Nations. http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm (accessed August 2, 2010).

———. 2001. Declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS. In S-26/2. General Assembly. http://www.un.org/ga/aids/docs/aress262.pdf (accessed August 2, 2010).

———. 2003. Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York: UN.

———. 2005. World summit outcome. In 60/1. General Assembly. http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan021752.pdf (accessed August 2, 2010).

UN Economic and Social Council. 2000. The right to the highest attainable standard of health. Geneva: UN.

———. 2004. Economic, social and cultural rights: The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. Report of the Special Rapporteur, Paul Hunt. Geneva: UN.

———. 2005. Economic, social and cultural rights: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Paul Hunt. Geneva: UN.

UNAIDS (The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS). 2009. Update on the impact of the economic crisis: HIV prevention and treatment programmes. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/economiccrisisandhivandaids61_en.pdf (accessed August 12, 2010).

———. 2010. Civil society. http://www.unaids.org/en/Partnerships/Civil+society/default.asp (accessed November 1, 2010).

UNAIDS/WHO. 2004. Guidance on ethics and equitable access to HIV treatment and care. Geneva: WHO.

WHO (World Health Organization). 1986. Ottawa charter for health promotion. In WHO/HPR/ HEP/95.1. Ottawa, Canada: First International Conference on Health Promotion.

Williams, J. R. 2009. World Medical Association Medical Ethics Manual, 2nd ed. Ferney-Voltaire Cedex: WMA.

Williams, T. P., M. Vibbert, L. Mitchell, and R. Serwanga. 2009. Health and human rights of children affected by HIV/AIDS in urban Boston and rural Uganda: A cross-cultural partnership. International Social Work 52(4):539-545.

WMA (World Medical Association). 2005. Declaration on the rights of the patient. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/l4/index.html (accessed June 1, 2010).

———. 2006. International code of medical ethics. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/c8/index.html (accessed June 1, 2010).

Youngkong, S., L. Kapiriri, and R. Baltussen. 2009. Setting priorities for health interventions in developing countries: A review of empirical studies. Tropical Medicine and International Health 14(8):930-939.

ANNEX 6-1

INTERNATIONAL GUIDELINES ON HIV/AIDS AND HUMAN RIGHTS

The UNAIDS 2006 International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights (consolidating Consultations from September 1996 and July 2002) are as follows:

-

States should establish an effective national framework for their response to HIV/AIDS which ensures a coordinated, participatory, transparent and accountable approach, integrating HIV/AIDS policy and program responsibilities across all branches of government.

-

States should ensure, through political and financial support, that community consultation occurs in all phases of HIV/AIDS policy design, program implementation and evaluation and that community organizations are enabled to carry out their activities, including in the field of ethics, law and human rights, effectively.

-

States should review and reform public health laws to ensure that they adequately address public health issues raised by HIV/AIDS, that their provisions applicable to casually transmitted diseases are not inappropriately applied to HIV/AIDS and that they are consistent with international human rights obligations.

-

States should review and reform criminal laws and correctional systems to ensure that they are consistent with international human rights obligations and are not misused in the context of HIV/AIDS or targeted against vulnerable groups.

-

States should enact or strengthen anti-discrimination and other protective laws that protect vulnerable groups, people living with HIV/AIDS and people with disabilities from discrimination in both the public and private sectors, ensure privacy and confidentiality and ethics in research involving human subjects, emphasize education and conciliation, and provide for speedy and effective administrative and civil remedies.

-

States should enact legislation to provide for the regulation of HIV-related goods, services and information, so as to ensure widespread availability of qualitative prevention measures and services, adequate HIV prevention and care information and safe and effective medication at an affordable price.

-

States should implement and support legal support services that will educate people affected by HIV/AIDS about their rights, provide free legal services to enforce those rights, develop expertise on HIV-related legal issues and utilize means of protection in addition to the courts, such as offices of ministries of justice, ombudsmen, health complaint units and human rights commissions.

-

States, in collaboration with and through the community, should promote a supportive and enabling environment for women, children and other vulnerable groups by addressing underlying prejudices and inequalities through community dialogue, specially designed social and health services and support to community groups.

-

States should promote the wide and ongoing distribution of creative education, training and media programs explicitly designed to change attitudes of discrimination and stigmatization associated with HIV/AIDS to understanding and acceptance.

-

States should ensure that government and private sectors develop codes of conduct regarding HIV/AIDS issues that translate human rights principles into codes of professional responsibility and practice, with accompanying mechanisms to implement and enforce those codes.

-

States should ensure monitoring and enforcement mechanisms to guarantee the protection of HIV-related human rights, including those of people living with HIV/AIDS, their families and communities.

-

States should cooperate through all relevant programs and agencies of the United Nations system, including the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, to share knowledge and experience concerning HIV-related human rights issues and should ensure effective mechanisms to protect human rights in the context of HIV/AIDS at the international level.