6

Dietary Intake and Nutritional Status

Barbara Devaney, the session’s moderator, began the session by pointing out that, of the three major components of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), the WIC food packages account for the largest proportion of WIC dollars spent. Moreover, the food packages are rich sources of the foods and nutrients known to be lacking in the diets of low-income women, infants, and children. Thus, a key question is how effective WIC is in changing the dietary intakes of its participants.

This session focused on the research agenda for studying the effects of WIC on dietary intakes. Nancy Cole addressed potential research concerning the dietary intake and nutritional status of women and children, and Nancy Krebs addressed research related to infants. Discussant Suzanne Murphy responded by focusing on an approach to address the research questions.

WOMEN AND CHILDREN

Presenter: Nancy Cole

WIC provides a package of foods for women and children with the objective of promoting healthful food choices, improving dietary intake, and improving nutritional status. Cole’s presentation considered which elements to examine when conducting research on the impact of the WIC food package and included suggestions for research related to each of these.

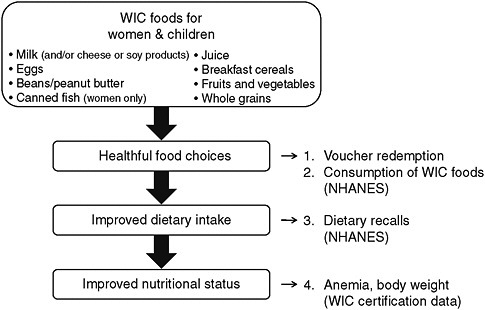

FIGURE 6-1 Measures for studying the impact of WIC food packages on women and children. NOTE: NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

SOURCE: Cole (2010).

Figure 6-1 illustrates measures that might be used for studying the impact of WIC food packages.

Early Steps Involving the WIC Food Package

To address the question of whether WIC improves dietary intakes and nutritional status, it is useful to consider two early steps as they relate to the food package: voucher pick-up and redemption, and the consumption of WIC foods.

Voucher Redemption

Prior research Administrative data are available that can be used to examine voucher pick-up and redemption, but they have seldom been used. The WIC Cost Containment Study (USDA/ERS, 2003) found that voucher pick-up across six states declined during the certification period, dropping from about 100 percent in the first month to between 73 and 84 percent by the sixth month.

Potential research Potential research on voucher redemption could include the following topics:

-

The impact of the revised WIC food packages on redemption, using a pre-versus-post comparison study or looking across states to observe the effects of differences in state policies (e.g., those specifying allowed foods), and

-

The effect of the revised WIC food packages on changes in redemption rates during the certification period and features of the revised packages to which the changes could be attributed.

Consumption of WIC Foods

Prior research Relatively little information is available concerning the extent to which WIC foods are consumed by WIC participants. Dietary data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination surveys (NHANES) during the period 1999–2004 have been used for this purpose. For example, the Food and Nutrition Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported that children participating in WIC were significantly more likely than other low-income children to consume WIC-approved cereals (USDA/FNS, 2008). However, NHANES data have a number of weaknesses: They cannot be used to measure impact, sample sizes are small for the populations of interest, and state identifiers are lacking. Cole stated that much can be learned from asking participants why they consumed only some or none of the WIC foods.

Potential research Potential research could examine the marginal effect of various factors on WIC participants’ consumption of WIC foods by determining the following:

-

The percentages of the foods in the food package consumed by the participant and by other family members, and

-

Variation of the WIC food consumption rate by category of food in the revised food packages—specifically, new foods, food categories with increased substitution, and food categories with decreased quantities.

Dietary Intake

Prior research on dietary intake has largely involved descriptive studies based on NHANES data. The studies have indicated that nearly all children from 1 through 4 years of age had adequate usual daily intake of all the vitamins (except E) and minerals that have defined Estimated Average Requirements.

Potential research to address the effect of revised WIC food packages on dietary intake could use the following approaches:

-

Replicate an earlier NHANES analysis in the period after implementation of the revised food packages; and

-

Use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Research Data Center to control for characteristics of state WIC food lists, which differ in the amount of choice allowed within each food category. Cole suggested that participating children in states with restrictive WIC food lists would provide a valid control group for lower-bound estimates of the impact of WIC; however, sample sizes in those states may be relatively small.

Nutritional and Health Status

The WIC Cost Containment Study (USDA/ERS, 2003) used a dose-response approach to estimating WIC impacts on nutritional status and health, with voucher redemption as the dose measurement. Using this method, WIC was found to have statistically significant beneficial effects on change in height for age and on probabilities related to the risk of underweight and anemia.

The following two possible descriptive analyses of change in nutritional and health status make use of the WIC Participants and Program Characteristics (WIC-PC) data:

-

For a sample of states, obtain a second WIC-PC extract 6 months after the WIC-PC submission and examine changes in status; and

-

Follow the approach in (1) but also obtain measures of voucher redemption for use in a dose-response analysis.

Summary of Potential Research

In summary, Cole’s research suggestions covered four topics related to the food package and dietary intake:

-

Voucher redemption Trends before and after revised food packages

-

Consumption of WIC foods (1) Analysis of NHANES and comparison of recent WIC food consumption with consumption before the implementation of revised food packages, possibly controlling for characteristics of states’ food lists; and (2) a new survey to understand the marginal effect of WIC on the consumption of WIC foods and reasons for not consuming the full WIC food package

-

Dietary intakes NHANES analysis of usual daily intakes of nutrients by WIC participants and non-participants compared with intakes before implementation of revised food packages

-

Nutritional/health status Analysis of administrative data from a sample of states

INFANTS AND YOUNG CHILDREN

Presenter: Nancy Krebs

In her presentation, Krebs reviewed data relating to dietary intake, growth, and iron status and provided the rationale for her WIC research priorities.

Dietary Intake

Data from the first Feeding Infant and Toddlers Study (FITS) (Ponza et al., 2004) indicate that at least 95 percent of infants 4 through 11 months of age consumed infant formula. Although 95 percent of the infants ages 7 through 11 months of age consumed cereals and purees, fewer than 5 percent consumed meats (the best sources of iron and zinc), and more than 50 percent consumed sweets and desserts.

FITS data indicate that less than 1 percent of formula-fed infants had usual nutrient intakes that were lower than the Estimated Average Requirement or mean intakes that were lower than the Adequate Intake. However, substantial proportions of breastfed infants had inadequate intakes of iron or zinc or both. Many infants in FITS were reported to have excessive energy intakes (Ponza et al., 2004).

In a study of children’s diet quality using the Healthy Eating Index as a standard, the Food and Nutrition Service compared the diets of WIC participants and eligible non-participants (USDA/FNS, 2008). Although the diets of the two groups were generally comparable, none were consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The investigators suggested that measures be taken to reduce children’s intake of saturated fat and sweetened beverages and to increase their intakes of whole grains, whole fruit (as opposed to juice), and a variety of vegetables (rather than mainly potatoes). The revised WIC food packages are well aligned with these suggested dietary changes.

Growth

In her analysis, Krebs used data on infant growth from a study by Black et al. (2004) that compared infants on WIC with those not on WIC because of access problems. In particular, Krebs converted z scores for length and weight to approximate percentiles, and she found that the means for both groups were well within the normal range on the Centers for Disease Con-

trol and Prevention (CDC) growth chart. She concluded that although the differences observed, including the modest shift of the overall distributions of growth parameters, were statistically significant, they were unlikely to be clinically important.

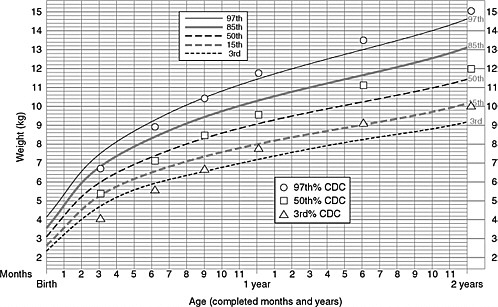

The World Health Organization (WHO) growth charts for breastfed infants (de Onis, 2006; WHO, 2010) differ from the 2000 CDC growth charts for infants (CDC, 2010a; Kuczmarski et al., 2000). Krebs illustrated this by plotting the 3rd, 50th, and 97th CDC percentiles on a WHO chart (Figure 6-2), and she noted that this difference has implications for evaluating growth.

Iron Status

Analyses of NHANES data have shown a marked decrease in the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia among infants and young children since 1971, but Krebs pointed out that this is very likely the result of encouraging the feeding of iron-fortified formula and the decrease in the use of whole cow milk (Cusik et al., 2008). (Krebs noted that the intake of iron-fortified cereal has been reported to decrease by infants’ eighth month.) Reported rates of iron deficiency in toddlers from the NHANES data range from 6.6 percent to 15.2 percent; for iron deficiency anemia they range from 0.9 to 4.4 percent. Higher rates have been reported in smaller series that include high-risk subpopulations.

Proposed Research Priorities

Priority One

According to Krebs, the highest priority for WIC research should be how to increase breastfeeding rates in the United States. Addressing this question would require a change in the culture and administration of WIC to allow interventional research.

Rationale In Krebs’ opinion, the data are overwhelmingly conclusive that WIC undermines breastfeeding in the United States. She said that the positive effects of breastfeeding-promotion programs, peer counseling, and related efforts are dwarfed by the provision of free formula for a full year. This free-formula policy is unique to the United States and is contrary to the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, the International Code of Marketing, and the global efforts of WHO to promote breastfeeding. A lack of breastfeeding has profound adverse health effects for infants, women, and society.

FIGURE 6-2 A comparison of CDC and WHO weight-for-age percentiles from birth to 2 years for girls. The WHO charts covering birth to 2 years were developed using data on breastfed children (de Onis et al., 2006). CDC now recommends that WHO growth standards be used in the United States for this age group (CDC, 2010b).

NOTE: CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCES: CDC (2010a); WHO (2010). Reprinted with permission from WHO.

Proposed study design Krebs’ proposal was to use a cluster-randomized trial to test the effect of not providing free formula for any infant from birth to 6 months of age (which is not the same as formula not being used at all). She suggested measuring the following outcomes: rates and duration of breastfeeding, growth and nutritional status from 0 to 24 months of age, dietary quality and feeding practices from 0 to 24 months of age, maternal body mass index at 6 months, medical expenses and utilization, and WIC participation rates.

Other Research Priorities

Because of time constraints, Krebs did not discuss her other research priorities, but she did quickly show slides that covered them. They are summarized in Box 6-1.

Summary

In closing, Krebs again emphasized that the nutritional status of infants and toddlers who are WIC participants is currently dominated by the use of formula. If and when breastfeeding rates increase, the entire care team will need to be aware of the importance of complementary feeding and of how to prevent and treat deficiencies. The beneficial impact of increasing breastfeeding duration could be profound.

|

BOX 6-1 Other Research Priorities

|

RESPONSE

Discussant: Suzanne Murphy

Murphy pointed out that the report WIC Food Packages: Time for a Change (IOM, 2006), for which she served as chairperson, includes a chapter on recommendations about evaluations of the revised WIC food package and identifies a number of variables to examine in such evaluations. In addition, Murphy described the importance of conducting periodic national evaluations of WIC. NHANES has strong clinical measures, but it is cross-sectional and has very limited samples of pregnant and lactating women and breastfed infants. A WIC survey, on the other hand, could track attitudes and behaviors, food purchasing patterns, the use of vouchers, and the mother-child dyad. It also could allow comparisons among the larger states. A longitudinal study could track changes in the health of the same WIC women and children over time and compare them with a control group. Other advantages of a periodic WIC survey, Murphy said, would be increased visibility of the program to the public and to Congress and the development of a source of data that might provide justification for funding WIC at a relatively high level.

Murphy suggested that outcomes could be tracked over time with NHANES and NHANES follow-ups if modules were added to those surveys that included additional details on WIC usage. A national WIC survey with a longitudinal component would be an attractive alternative to determine whether WIC has a long-term effect on the health of children that participate in the program. The goal would be to complement other types of research, not to replace them. Funding for a WIC survey might be sought from Congress. A recurring survey would provide justification for a consistent level of funding to support this activity.

GROUP DISCUSSION

Moderator: Barbara Devaney

Much of the discussion centered on Krebs’ suggested study that would examine the effects of providing no free formula to WIC mothers for the first 6 months after giving birth. Hirschman said that USDA does not have the authority to conduct the type of study proposed; an act of Congress would be required. Many of the comments included strong support for breastfeeding but raised concerns about Krebs’ proposal. The suggested alternate approaches included:

-

Allow free formula, but make it more difficult to obtain.

-

Consider providing only generically labeled formula.

-

Engage all care providers in support for breastfeeding.

-

Time breastfeeding messages appropriately.

-

Intensify support for all mothers in providing early infant feeding that is adequate and appropriate.

-

Establish an environment in the United States in which breastfeeding is not viewed as painful, too much work, or insufficient for the infant and in which women can continue breastfeeding even if working.

SUMMARY OF SUGGESTED RESEARCH TOPICS

The first set of research proposals made during the session focused on ways to examine the dietary and nutrient intake of women and children, including analyzing data on voucher redemption and the consumption of WIC foods. Careful analyses of state administrative data would provide useful information. The second major proposal was for a cluster-randomized controlled trial to examine how to increase breastfeeding in the United States. The third major proposal was for a longitudinal study, perhaps as a part of a periodic national WIC survey, to track a variety of outcomes associated with WIC participation.

REFERENCES

Black, M. M., D. B. Cutts, D. A. Frank, J. Geppert, A. Skalicky, S. Levenson, P. H. Casey, C. Berkowitz, N. Zaldivar, J. T. Cook, A. F. Meyers, and T. Herren. 2004. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children participation and infants’ growth and health: A multisite surveillance study. Pediatrics 114(1):169–176.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2010a. CDC Growth Charts. http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/cdc_charts.htm (accessed September 24, 2010).

CDC. 2010b. WHO Growth Standards Are Recommended for Use in the U.S. for Infants and Children 0 to 2 Years of Age. http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/who_charts.htm (accessed September 24, 2010).

Cole, N. 2010. Dietary intake and nutritional status: Women and children. Presented at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Impacts of WIC––Planning a Research Agenda, Washington, DC, July 20–21.

Cusick, S. E., Z. Mei, D. S. Freedman, A. C. Looker, C. L. Ogden, E. Gunter, and M. E. Cogswell. 2008. Unexplained decline in the prevalence of anemia among us children and women between 1988–1994 and 1999–2002. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 88(6):1611–1617.

de Onis, M. 2006. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics 95(Suppl. 450):76–85.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2006. WIC Food Packages: Time for a Change. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kuczmarski, R. J., C. L. Ogden, L. M. Grummer-Strawn, K. M. Flegal, S. S. Guo, R. Wei, Z. Mei, L. R. Curtin, A. F. Roche, and C. L. Johnson. 2000. CDC growth charts: United States. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics (314):1–27. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad314.pdf (accessed September 24, 2010).

Ponza, M., B. Devaney, P. Ziegler, K. Reidy, and C. Squatrito. 2004. Nutrient intakes and food choices of infants and toddlers participating in WIC. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 104(Suppl. 1):S71–S79.

USDA/ERS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Economic Research Service). 2003. Assessment of WIC Cost-Containment Practices: Final Report. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/efan03005/efan03005.pdf (accessed September 2, 2010).

USDA/FNS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service). 2008. Diet Quality of American Young Children by WIC Participation Status: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. Alexandria, VA: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/ora/menu/Published/WIC/FILES/NHANES-WIC.pdf (accessed September 2, 2010).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010. The WHO child growth standards. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/en (accessed September 24, 2010).