7

Nutrition Education in WIC

The two presentations in this session, moderated by Shannon Whaley, represent a collaborative effort of the two presenters, Lorrene Ritchie and Marilyn Townsend. Ritchie presented an overview of past studies; then Townsend addressed research design and timing and introduced a joint proposal for a study. The discussants (Maureen Black and Loren Bell) expanded on the presentations and raised additional questions. All five participants in this session are members of the nutrition education group mentioned later in this chapter.

OVERVIEW OF PAST STUDIES

Presenter: Lorrene Ritchie

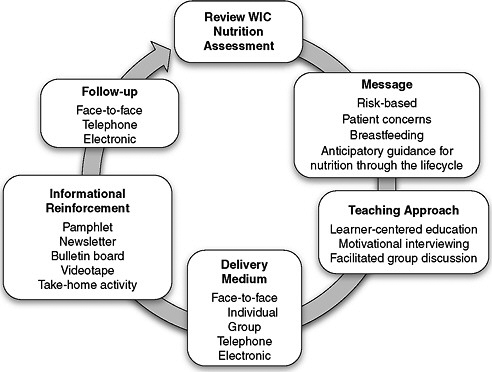

Nutrition education in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) involves helping participants understand the importance of nutrition and physical activity to their health and also learn how to make positive changes in those habits with the goal of reducing health risks including obesity. The process of delivering nutrition education in WIC is illustrated in Figure 7-1. The boxes in the figure each contain several entries because effective nutrition education interventions may involve components from several teaching approaches and delivery mediums. The review of studies that follows was intended to illustrate specific points and characterize the current state of knowledge on nutrition education in WIC.

FIGURE 7-1 Process of delivering nutrition education in WIC.

SOURCE: USDA/National Agricultural Library (2006).

Participant Needs

The first rule in most behavior change models is to adapt the approach so as to best meet the participants’ needs. Studies on participant needs have shown that 80 to 95 percent of WIC participants indicated satisfaction with the nutrition education (Nestor et al., 2001; USDA/FNS, 2000), but they also identified barriers, such as repetition and a lack of activities available for the children while they were waiting for their mothers (Woelfel et al., 2004). Participant preferences included child care, facilitated discussions, more talking by the participants, and cooking classes.

Approaches

Most of the studies on approaches have been of the type called WIC plus studies, in which augmented WIC services are compared with the usual services using convenience samples. Findings from these studies can be used to inform efforts to improve the delivery of WIC nutrition education, but these studies are not necessarily representative of usual practice or the

resources normally available in WIC. Facilitated group discussion has been shown to improve self-efficacy (Abusabha et al., 1998) but not knowledge (USDA/FNS, 2001a) or maternal weight (Krummel et al., 2010). In other studies, learner-centered education improved folate intake (Cena et al., 2008) and the adoption of practices consistent with increasing fruit and vegetable intake (Gerstein et al., 2010). Havas et al. (1998) reported that peer education and support improved knowledge, led to a higher stage of change,1 increased self-efficacy, and increased the intake of fruits and vegetables. Similarly, Ikeda and colleagues (2002) reported that peer support increased the intake of several important food groups. On the other hand, Chang et al. (2010) reported no effect of peer education on diet or body weight. Whaley and colleagues (2010) reported that motivational interviewing had beneficial effects on children’s dietary and TV habits. Ritchie noted that she had found no studies that compared individual one-on-one education to group education approaches.

Messages

Ritchie identified studies that address four of the many subjects that are part of the WIC educational effort: cooking (Birmingham et al., 2004; Tessaro et al., 2007), low-fat milk (Ritchie et al., 2010; USDA/ERS, 2007), physical activity (Fahrenwald et al., 2004), and fruit and vegetable education plus coupons (Anderson et al., 2001; Whaley, submitted). In most cases, the studies found significant effects on behavior change and attitudes. Few studies have used randomized controlled designs, however. The question remains, “What messages are most important to address with WIC participants?”

Audience

Most of the WIC nutrition education studies address pregnant or postpartum women (USDA/FNS, 2000). Few have been targeted at preschool children (USDA/FNS, 2001b) or staff (Crawford et al., 2004).

Technology

The use of technology is emerging as a way to provide nutrition education to a larger number of WIC participants, with the additional goal of doing it in a cost-effective manner. Relatively few studies have been published on the use of new technological methods. The ones Ritchie reviewed examined a website (Bensley et al., 2006), touch screen video (USDA/FNS,

2001a), interactive CD-ROMs (Block et al., 2000; Campbell et al., 2004), and computer kiosks (Carroll et al., 1996; Trepka et al., 2010). The studies suggest that technological methods are well-liked, but their impact and cost-effectiveness are not well known.

State-Wide Campaigns

Three state-wide nutrition education campaigns have reported positive results in modifying participant behaviors, but the results depended on using the participants as their own controls and examining their behavior pre- and post-campaign. Furthermore, the studies were limited by not including comparisons to other approaches to delivering nutrition education in WIC. The topics of the campaigns included television viewing (Johnson et al., 2005), family meals (Johnson et al., 2006), and new foods in the WIC food packages (Ritchie et al., 2010).

FUTURE RESEARCH

Presenter: Marilyn Townsend

Research Design and Timing

After reviewing studies of WIC nutrition education, Townsend said that the most common design had used a pretest followed by an intervention and then a posttest. It would be valuable to consider more complex designs, she said. To improve study designs, more attention should be paid to the possibility of longitudinal design, random selection and assignment to minimize selection bias, appropriate comparison or control groups, multivariate analysis to account for moderating variables, validated outcome measures, the use of a number of states and sites to take the research beyond the clinic level of delivery and analysis, and the method of data collection.

Suggested Reporting Methods

Adoption of TREND statement for describing study To achieve more systematic reviews of WIC interventions and possibly to allow for the merging of small datasets, Townsend and Ritchie recommended that investigators follow the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Non-randomized Designs (TREND) statement (Des Jarlias et al., 2004) when reporting primary prevention intervention (nutrition education) studies related to WIC, whether non-randomized or randomized. Developed by 26 journal editors and experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the TREND statement identifies 22 critical elements that

should be included in reports. In particular, researchers should be careful to provide detailed information on intervention timing, dosage, effect size, intervention content, control content, participant assignment, and the unit of analysis.

Strategy statement for describing intervention A strategy statement is a description of the procedures used in the intervention that is detailed enough that another investigator could replicate the intervention. Such a strategy statement involves the systematic specification of each theory-driven strategy used in the intervention. Such information is crucial, Townsend emphasized, because we do not yet know what behavioral change strategies work with WIC clients, and we need to uncover what works, how well each strategy works, and why it works. Michie and Abraham (2004) investigated behavior change interventions in many health education fields and identified 26 evidence-based techniques or strategies, five of which appeared to be especially important (Michie et al., 2009).

Potential Research Questions

Townsend identified eight categories pertaining to research on nutrition education in WIC: the subject of the research, dose, approach, delivery, reinforcement and follow-up, educators, participants, and data sets.

Subject Townsend suggested that the following questions be considered: Should the focus be on obesity prevention? Should the research be organized as campaigns with common themes and timelines? Should it include child feeding and development or cooking and shopping, or both?

Dose Information is needed on whether four education contacts per year are sufficient, how session attendance can be increased, and whether WIC nutrition education contacts are synergistic with other nutrition education programs, such as Head Start and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Education (SNAP-Ed).

Approach There are insufficient data regarding the optimal approaches to WIC nutrition education, including the cost-effectiveness of the various approaches. These approaches include learner-centered education, facilitated group discussion, peer-led discussions, motivational negotiation, anticipatory guidance, and interactive or experiential education (such as cooking demonstrations, taste testing, field trips).

Delivery Similarly, there are insufficient data about the optimal methods of delivery. In addition to the methods mentioned by Ritchie, methods to

consider might include home or workplace visits and contacts in the WIC waiting area.

Reinforcement and follow-up Among the reinforcing approaches that could be tested are email or text messages, take-home materials, social marketing, self-monitoring (see Havas et al., 1998, for an example), and other home activities.

Educators Key questions concerning the educators or “messengers” might include the following: To what extent is staff wellness important? What are the components of optimal training and staff development for nutrition educators? What are the best methods to reduce turnover?

Participants It is unclear to what extent nutrition education should be directed at children or significant others, or both; and little is known about overcoming the barriers to effective nutrition education.

Data sets The nutrition education group agreed that no existing data sets would provide the information needed to address the questions that need to be studied.

Proposed Study

As a next step in research design, Townsend and Ritchie proposed a study that would be less expensive than a national study. The study addresses the question, “Can WIC nutrition education reduce the risk of obesity?” The proposed elements of the study are:

-

Delivery approaches Within the WIC population, compare the impacts of three delivery approaches: (1) a learner-centered model (a group at a clinic), (2) an online learning-at-home model (an individual at home), and (3) a counseling model as a control (one-on-one at clinic).

-

Design In each of four to six states with different demographics, select eight clinics: four for approach 1, and four for approach 3 (above). The online clients (approach 2) should be volunteers recruited from all the study clinics.

Because of a lack of appropriate controls, Townsend said the study would need to focus on relative differences. Results from different sites could be merged using appropriate analyses. The proposed design would be an informative next step and would be less expensive than a national study.

RESPONSE

Discussant: Maureen Black

After showing video clips that illustrated some mother–child interactions, Black briefly addressed aspects of mealtime and food behaviors; policy, environmental, and developmental issues that could influence or be a part of nutrition education in WIC; and methodological issues related to education and behavior change.

Mealtime and Food Behaviors

Maternal feeding behaviors are influenced by the infant or child’s behavior, as can be clearly seen by observing a mother–infant dyad when breastfeeding. Children’s intake is influenced by the availability of food; the mealtime context; and mealtime interactions with the caregiver, which might be responsive, controlling, indulgent, or uninvolved. Several studies report negative effects of excessive control (Faith et al., 2004; Fisher and Birch, 1999, 2002; Lee et al., 2001). The reasons that parents may exert excessive control include concerns about the child’s health and body size, time constraints, and food insecurity. Building on concepts from the field of child development, investigators have begun to study whether responsive feeding leads to healthful mealtime behavior and then to healthful growth.

Other Topics Pertinent to Nutrition Education

Black noted that the following topics, which had been mentioned earlier in the workshop, are relevant to nutrition education: topics in the areas of policies and economics, family structure and function, prenatal development, and obesity. She then added two relevant topics to the list: the “nutrition transition,” which is characterized by an easy access to ready-to-eat food and reduced energy expenditure; and infants’ and toddlers’ increasing desire for autonomy.

Methodological Issues and Strategies

Because didactic education has limitations, WIC has incorporated learner-centered education, tailored messages, and various other strategies, such as motivational interviewing to elicit change. Knowledge and intentions are necessary but not sufficient for effecting behavioral change. Black reminded the audience that research questions related to dose and incentives were raised by previous presenters.

|

BOX 7-1 Comparative Effectiveness Design Elements

|

Black proposed that research take the form of comparative effectiveness studies. With this method, intervention A is compared with intervention B rather than with a control group. The basic elements in this method are given in Box 7-1. With replication and the sharing of findings across sites, this strategy could lead to quality improvement within WIC and to more integrated systems.

RESPONSE

Discussant: Loren Bell

Bell began his response by providing context for his perspectives and then suggested a number of topics for research.

Context

Bell’s food assistance and nutrition research team has a project covering a number of states, most of which are in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) western region but some of which are in the mountain plains and the Midwest. Over approximately the past 4 years, team members have visited 19 states and 60 local WIC agencies. They have conducted Web surveys, interviewed more than 600 local WIC staff who provide nutrition education, held focus groups or intercept interviews with 1,800 WIC clients about nutrition education, and observed the delivery of services.

The team members observed very large variations in the delivery of nutrition education and identified three major issues. The first issue concerned the demands of the WIC computer system and the need to document eligibility. The staff may be unable to apply their skills in learner-centered approaches, for example, because of the need to ask many specific computer-directed questions, many of which the client may not understand. The second issue is the widespread use of a deficit model. In response to

this issue, the research team has been focusing on the affirmation of positive behaviors as a potentially more effective approach to behavior change. The third issue is effective use of time. Staff members indicate that they have insufficient time for learner-centered education; whereas the clients have long waiting times.

Suggested Topics for Research

A major emphasis of the project that Bell’s team has been carrying out is the design of evaluation methodologies to determine outcomes that are reasonable given what can actually be accomplished in the WIC site. Based on findings from that project, Bell identified seven major questions for research:

-

How is nutrition education delivered? The context should be framed before the interventions are described.

-

How can one evaluate the intervention in view of interventions from other programs? Because it is nearly impossible to separate the effects of a WIC intervention from a SNAP-Ed nutrition intervention2 (assuming that both are directed toward promoting the same behavior change, such as the consumption of low-fat milk), it is important to be realistic and practical concerning what can be measured in WIC.

-

What kind of outcome is desired? Questions arise about the significance of moving to a higher stage of change (for example, moving from the contemplation stage to the preparation stage, when one actually prepares to make a specific change) and of making specific behavioral changes.

-

How do clients like to learn? Focus groups and intervention intercept interviews have indicated that clients are open to the use of electronic media, both for nutrition education contacts and reminders or messages.

-

How do factors that contribute to health disparities relate to nutrition education? How far a mother lives from a grocery store that carries fresh fruits and vegetables is an example of a factor that should be considered in nutrition education.

-

What is WIC’s role in providing nutrition education services to postpartum women and significant others? Women reported feeling

-

ignored because the attention is focused on the baby or on breastfeeding. Males said that WIC has nothing to offer them.

-

How should self-reporting by clients be addressed? Members of focus groups reported that the best thing about WIC is the people. One reason given for erroneous self-reporting was that WIC participants did not want to disappoint staff.

Closing Remarks

Although many issues concerning nutrition education will need to be addressed in the future, Bell urged the initial focus to be on what nutrition education is and then on the appropriate outcome for the interventions.

GROUP DISCUSSION

Moderator: Shannon E. Whaley

The wide-ranging discussion involved many participants and addressed a number of points, which are summarized below:

-

Methods for reaching out to clients WIC health professionals and clients appear to have different views about the preferred methods for reaching out to clients. One survey of WIC personnel listed fact sheets, brochures and pamphlets, and recipes, while the clients said they would like WIC to use text messages and social networking. Even clients in the Pacific Islands are using electronic media and would like WIC to do so also. It was noted that preferences are often expressed in terms of an idealized state rather than with consideration to what will actually work well. In California, for example, a decline in literacy has been noted among low-income clientele, raising questions about how to reach them effectively. Not enough research has been conducted to determine the extent to which electronic media can be used in WIC and whether it will have any effect on nutrition.

-

Social networking There is considerable evidence that social networks have power to influence behavior change. The theory behind social learning is well-established, involving such basic concepts as modeling and outcome expectancies. Small electronic social networks might be created that could operate and have influence beyond the site of the intervention.

-

Partnerships with other programs To move the research agenda forward, it could be useful to work together with other programs (e.g., SNAP-Ed) and share the burden of research.

-

Reporting of research findings in journals The TREND guidance for reporting research findings is valuable. The extent to which investigators are following the guidance is not being evaluated (however, the development of rating scales was suggested for this purpose), and many journal editors are publishing papers that do not conform to the guidance statement. Because researchers cannot stay within the maximum word count for articles if they provide all the information specified in the guidance, alternative ways to provide the information (such as an addendum to an electronic version of the article) need to be found.

-

Evaluation of individual WIC programs Questions arose regarding the methods that USDA uses to evaluate individual programs, specifically related to the fact that the monitoring methods tend to focus on the negative. Some states have restructured their monitoring tools to emphasize an approach based on positive affirmation rather than addressing only what was wrong.

-

Maternal factors Nutrition education needs to consider maternal depression, different temperaments, and general parenting skills. It was noted that some caregivers do not recognize that they are using food for a behavioral purpose (e.g., giving food to a child to calm the child).

-

Humor Consider ways to make learning fun.

SUMMARY OF SUGGESTED RESEARCH TOPICS

The research suggestions made during this session focused on methods and on nutrition education strategies that are intended to reduce the risk of obesity. Many research questions were raised concerning identification of the message, message delivery, appropriate outcomes, consideration of environmental effects and nutrition education efforts by other programs, and several other factors. Specific proposals by the presenters included the use of comparative effectiveness studies in numerous sites in four to eight states and the merging of results through appropriate analysis. Following TREND guidelines and writing strategy statements may be helpful in reports provided to funders and in journal papers.

REFERENCES

Abusabha, R., C. Achterberg, J. McKenzie, and D. Torres. 1998. Evaluation of nutrition education in WIC. Evaluation of nutrition education in a supplemental food and nutrition program in New Mexico. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences: From Research to Practice 90(4):98–104.

Anderson, J. V., D. I. Bybee, R. M. Brown, D. F. McLean, E. M. Garcia, M. L. Breer, and B. A. Schillo. 2001. 5 a day fruit and vegetable intervention improves consumption in a low income population. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 101(2):195–202.

Bensley, R. J., J. J. Brusk, J. V. Anderson, N. Mercer, J. Rivas, and L. N. Broadbent. 2006. WICHealth.org: Impact of a stages of change-based Internet nutrition education program. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior 38(4):222–229.

Birmingham, B., J. A. Shultz, and M. Edlefsen. 2004. Evaluation of a five-a-day recipe booklet for enhancing the use of fruits and vegetables in low-income households. Journal of Community Health 29(1):45–62.

Block, G., M. Miller, L. Harnack, S. Kayman, S. Mandel, and S. Cristofar. 2000. An interactive CD-ROM for nutrition screening and counseling. American Journal of Public Health 90(5):781–785.

Campbell, M. K., E. Carbone, L. Honess-Morreale, J. Heisler-Mackinnon, S. Demissie, and D. Farrell. 2004. Randomized trial of a tailored nutrition education CD-ROM program for women receiving food assistance. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior 36(2):58–66.

Carroll, J. M., C. Stein, M. Byron, and K. Dutram. 1996. Using interactive multimedia to deliver nutrition education to Maine’s WIC clients. Journal of Nutrition Education 28(1):19–25.

Cena, E. R., A. B. Joy, K. Heneman, G. Espinosa-Hall, L. Garcia, C. Schneider, P. C. Wooten Swanson, M. Hudes, and S. Zidenberg-Cherr. 2008. Learner-centered nutrition education improves folate intake and food-related behaviors in nonpregnant, low-income women of childbearing age. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 108(10):1627–1635.

Chang, M.-W., S. Nitzke, and R. Brown. 2010. Design and outcomes of a mothers in motion behavioral intervention pilot study. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior 42(3 Suppl.):S11–S21.

Crawford P. B., W. Gosliner, P. Strode, S. E. Samuels, C. Burnett, L. Craypo, and A. K. Yancey. 2004. Walking the talk: Fit WIC wellness programs improve self-efficacy in pediatric obesity prevention counseling. American Journal of Public Health 94(9):1480–1485.

Des Jarlais, D. C., C. Lyles, and N. Crepaz. 2004. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health intreventions: The TREND statement. American Journal of Public Health 94(3):361–366.

Fahrenwald, N. L., J. R. Atwood, S. N. Walker, D. R. Johnson, and K. Berg. 2004. A randomized pilot test of “moms on the move”: A physical activity intervention for WIC mothers. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 27(2):82–90.

Faith, M. S., R. I. Berkowitz, V. A. Stallings, J. Kerns, M. Storey, and A. J. Stunkard. 2004. Parental feeding attitudes and styles and child body mass index: Prospective analysis of a gene-environment interaction. Pediatrics 114(4):e429–436.

Fisher, J. O., and L. L. Birch. 1999. Restricting access to foods and children’s eating. Appetite 32(3):405–419.

Fisher, J. O., and L. L. Birch. 2002. Eating in the absence of hunger and overweight in girls from 5 to 7 y of age. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 76(1):226–231.

Gerstein, D. E., A. C. Martin, N. Crocker, H. Reed, M. Elfant, and P. Crawford. 2010. Using learner-centered education to improve fruit and vegetable intake in California WIC participants. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior 42(4):216–224.

Havas, S., K. Treiman, P. Langenberg, M. Ballesteros, J. Anliker, D. Damron, and R. Feldman. 1998. Factors associated with fruit and vegetable consumption among women participating in WIC. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 98(10):1141–1148.

Ikeda, J. P., L. Pham, K.-P. Nguyen, and R. A. Mitchell. 2002. Culturally relevant nutrition education improves dietary quality among WIC-eligible Vietnamese immigrants. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior 34(3):151–158.

Johnson, D. B., D. Birkett, C. Evens, and S. Pickering. 2005. Statewide intervention to reduce television viewing in WIC clients and staff. American Journal of Health Promotion 19(6):418–421.

Johnson, D. B., D. Birkett, C. Evens, and S. Pickering. 2006. Promoting family meals in WIC: Lessons learned from a statewide initiative. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 38(3):177–182.

Krummel, D., E. Semmens, A. M. MacBride, and B. Fisher. 2010. Lessons learned from the mothers’ overweight management study in 4 West Virginia WIC offices. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior 42(3 Suppl.):S52–S58.

Lee, Y., D. C. Mitchell, H. Smiciklas-Wright, and L. L. Birch. 2001. Diet quality, nutrient intake, weight status, and feeding environments of girls meeting or exceeding recommendations for total dietary fat of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics 107(6): e95–121.

Michie, S., and C. Abraham. 2004. Interventions to change health behaviours: Evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychology & Health 19(1):29–49.

Michie, S., C. Abraham, C. Whittington, J. McAteer, and S. Gupta. 2009. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: A meta-regression. Health Psychology 28(6):690–701.

Nestor, B., J. McKenzie, N. Hasan, R. AbuSabha, and C. Achterberg. 2001. Client satisfaction with the nutrition education component of the California WIC program. Journal of Nutrition Education 33(2):83–94.

Prochaska, J. O., C. C. DiClemente, and J. C. Norcross. 1992. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. The American Psychologist 47(9): 1102–1114.

Ritchie, L. D., S. E. Whaley, P. Spector, J. Gomez, and P. B. Crawford. 2010. Favorable impact of nutrition education on California WIC families. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 42(3 Suppl.):S2–S10.

Tessaro, I., S. Rye, L. Parker, C. Mangone, and S. McCrone. 2007. Effectiveness of a nutrition intervention with rural low-income women. American Journal of Health Behavior 31(1):35–43.

Trepka, M. J., F. L. Newman, F. G. Huffman, and Z. Dixon. 2010. Food safety education using an interactive multimedia kiosk in a WIC setting: Correlates of client satisfaction and practical issues. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 42(3):202–207.

USDA/ERS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Economic Research Service). 2007. Using Point-of-Purchase Data to Evaluate Local WIC Nutrition Education Interventions: Feasibility Study. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://hdl.handle.net/10113/32797 (accessed September 16, 2010).

USDA/FNS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service). 2000. WIC Nutrition Education Assessment Study Final Report, September 1998. Alexandria, VA: USDA/FNS.

USDA/FNS. 2001a. WIC Nutrition Education Demonstration Study: Prenatal Intervention. Washington, DC: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/Menu/Published/WIC/FILES/WICNutEdPrenatal.pdf (accessed September 30, 2010).

USDA/FNS. 2001b. WIC Nutrition Education Demonstration Study: Child Intervention. Washington, DC: USDA/FNS. http://hdl.handle.net/10113/38348 (accessed September 16, 2010).

USDA/National Agriculture Library. 2006. WIC Works Resource System: WIC Program Nutrition Education Guidance. http://www.nal.usda.gov/wicworks/Learning_Center/ntredguidance.pdf (accessed September 24, 2010).

Whaley, S. E., L. D. Ritchie, P. Spector, J. Gomez, and P. B. Crawford. Submitted. Revised WIC food package produces intended behavior change in WIC families. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior

Whaley, S. E., S. McGregor, L. Jiang, J. Gomez, G. Harrison, and E. Jenks. 2010. A WIC-based intervention to prevent early childhood overweight. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 42(3 Suppl.):S47–S51.

Woelfel, M. L., R. AbuSabha, R. Pruzek, H. Stratton, S. G. Chen, and L. S. Edmunds. 2004. Barriers to the use of WIC services. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 104(5):736–743.