2

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Over the last decade, a controversy has arisen regarding whether Blue Water Navy Vietnam veterans were potentially exposed to the same tactical herbicides as were their fellow veterans who served on the ground or on the inland waterways in Vietnam. This chapter presents a brief chronology of the issues surrounding the question of whether they were potentially exposed to herbicides, particularly Agent Orange and its contaminant 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, also referred to as TCDD, and thus should be eligible for compensation. A summary of American involvement in Vietnam, focusing on the role of the Blue Water Navy, is presented first, including a discussion of the missions and roles of the several Navy sectors, such as the Brown Water Navy and the Coast Guard. A synopsis of the legislation regarding veterans and Agent Orange since the Vietnam War and of the recent legal issues that have arisen over Blue Water Navy veterans’ compensation then follows.

AMERICAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE VIETNAM WAR

American involvement in Southeast Asia did not begin with the Vietnam War. After World War II, when Vietnam became an independent nation, the US government supported France’s interest in repossessing Vietnam, its former colony. Its support grew primarily out of an American interest in building alliances with Western European nations that would fight against the Soviet Union’s expansion efforts of the early Cold War. After the Communist victory in China in 1949 and the beginning of the Korean War in 1950, the US government expanded its financial and advisory support of the French in the French-Vietnamese conflict (also known as the First Indochina War). In 1950, the US Military Assistance Advisory Group-Indochina (MAAG-Indochina) was established, and small numbers of American military personnel went to Saigon to supervise the material support that the United States was providing to the French (Marolda, 1994).

In 1954, the Vietnamese defeated the French forces, and the two sides agreed to a temporary, 2-year partition of Vietnam at the 17th parallel, with the French military forces retreating to the south before elections were held and a unified government could be established. The US government publicly supported that plan but privately provided funding and other support for the development of an independent, anticommunist, pro-American state in the south, the Republic of Vietnam. In the late 1950s, the government of North Vietnam, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, ratcheted up its efforts to take over South Vietnam and merge the two countries; in 1960, it established the National Liberation Front (the NLF, commonly known to Americans as the Viet Cong) to fight against the South Vietnam government (Appy, 1993; Marolda, 1994). In August 1964, shots were allegedly fired at the American destroyer USS Maddox off the coast of North Vietnam in the Gulf of Tonkin, where it was conducting intelligence-gathering on behalf of the Republic of Vietnam. President Lyndon Johnson ordered retaliatory air strikes on North Vietnam, and Congress later passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, sending large numbers of US troops to Vietnam. US troop levels in South Vietnam rapidly rose from 23,000 ground troops in 1964 to 185,000 in 1965 and peaked in 1968 with 536,000 ground troops (Appy, 1993).

In early 1968, the “Tet Offensive” campaign by the NLF and South Vietnamese irregulars began a period of intense fighting (Turley, 2009) and helped to turn an already disillusioned American public more sharply against the war. President Johnson ordered a slow withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam. American troop withdrawal began in 1969, and the transfer of military equipment and leadership responsibilities to the South Vietnamese government (known as the Vietnamization of the war effort) became a larger focus of the American military. American troop levels decreased rapidly thereafter, and in 1973 after the Paris Peace Accord, virtually all remaining American troops were withdrawn. Fighting continued between North Vietnam and South Vietnam, however, until April 30, 1975, when Saigon, the capitol of South Vietnam, was captured by the North Vietnamese, and the South Vietnamese army surrendered.

The Blue Water Navy in the Vietnam War

The Blue Water Navy commonly refers to ships designed for open-ocean sailing and by association to the sailors assigned to those ships.

For example, the quintessential Blue Water Navy ship is the aircraft carrier, which can easily sail across an ocean but is less able to enter coastal waters (only in large deep-water ports) or to travel on inland waters. The Blue Water Navy is often juxtaposed with the Brown Water Navy, which comprises vessels that are best suited for operations very close to shore or on inland waters, such as rivers and bays, and are often not seaworthy for extended trips or for rough weather. In Vietnam, the quintessential Brown Water Navy vessels were the river patrol boat and the fast patrol boat (also known as the swift boat).

Another definition of the Blue Water Navy has developed with regard to the Vietnam War for legal purposes in determining eligibility for a presumptive service connection of diseases associated with exposure to tactical herbicides. In the present report, blue water refers to the more narrow legal definition of persons who served in the Navy during the Vietnam War and were stationed on ships that spent time in the waters offshore of Vietnam but never entered inland waters or set foot on land in Vietnam.

The Seventh Fleet, which is the section of the US Navy Pacific Fleet permanently stationed in the Western Pacific, had a presence in Vietnam and Vietnamese waters dating to 1950 as part of MAAG-Indochina. Navy personnel in Saigon supervised the transfer of naval supplies, including several aircraft carriers and over 400 other ships, first to the French and later to the South Vietnamese government. The Navy also provided training and advice to the nascent South Vietnamese Navy and executed shows of force of US ships in the waters surrounding North Vietnam and South Vietnam in support of the South Vietnamese government. In the early 1960s, the fleet increased; by 1965, Navy ships were involved in a wide array of blue-water and brown-water operations in and around Vietnam. At the peak of American involvement in the Vietnam War, in 1968, there were 38,000 Navy personnel in NAVFORV (Naval Forces Vietnam); this decreased to about 17,000 by the end of 1970 (Marolda, 1994).

By the end of the War, the Navy played a minimal role in near-shore and in-country activities. The Treaty of Paris limited the number of American military personnel who could be involved in any military assistance to the Republic of Vietnam, and the Navy’s main contribution was to assist in the evacuation of Americans (military and civilian) and Vietnamese refugees from South Vietnam. The Navy was also involved in the evacuation of Cambodia.

American naval operations in the Vietnam War had multiple goals during the period of 1965 to 1973, but most operations can be classified as aerial bombing and surveillance, surface interdiction of supplies along the coast and inland waterways, gunfire support, logistical support, military advising, and humanitarian efforts (Marolda, 1994).

Offshore Air Operations

Aircraft carriers and their affiliated combat and support ships conducted numerous aerial bombing campaigns throughout the war. Those operations were intended both to damage enemy equipment and to affect morale. Carrier ship groups comprised a flagship aircraft carrier and multiple destroyers, cruisers, and support ships that stored ammunition, fuel, and other supplies (also referred to as carrier divisions or carrier strike groups). Carrier ship groups also participated in aerial interdiction and surveillance missions and conducted search-and-rescue missions for downed pilots. Examples of substantial carrier bombing operations include Operation Flaming Dart; Operation Rolling Thunder, which was an aerial bombing campaign over North Vietnam; and Operation Barrel Roll, which targeted Laos.

Carrier groups assigned to bombing operations would often be rotated into active bombing duties for a period of days or a month, during which a carrier group was responsible for running air bombing operations for a particular number of hours per day in one of the two major offshore operating areas used by the Navy in Vietnam (Yankee Station off northern South Vietnam and Dixie Station in the south), which were interspersed with short visits to the Subic Bay naval base in the Philippines. Carrier ship groups involved in bombing campaigns aimed at North Vietnam and Laos were often based at Yankee Station, which was about 100 miles offshore of South Vietnam due east of Dong Hoi in the Gulf of Tonkin. Carriers engaged in bombing missions over South Vietnam were also based at Dixie Station, which was about 80 miles southeast of Cam Ranh Bay in the South China Sea. Those operations did not routinely move carriers close to the Vietnam coastline.

At any given time, two to four carrier groups each were on active duty at Yankee Station and Dixie Station. Carrier crews varied in size depending on the class of the ship, but each carrier required a crew of about 3,000 to 5,500 men. Those crews were by far the largest in the fleet and thus a substantial proportion of sailors who served in the Blue Water Navy in Vietnam served aboard carriers. Destroyers carried

complements of several hundred men, and cruisers generally 1,000–1,400 men.

Coastal Surface Surveillance and Interdiction

Blue Water Navy ships also patrolled the coast of South Vietnam and adjoining countries to intercept vessels attempting to smuggle troops or supplies to the enemy. Destroyers and cruisers worked with spotter planes to identify and destroy enemy vessels, and their efforts complemented the work of the smaller brown-water ships and boats that would patrol shallow waters close to shore and inland waterways.

Examples of substantial surface interdiction operations included Operation Sea Dragon (1966–1968), which operated along the coast of North Vietnam, and Operation Market Time (1965–1973), which focused on the South Vietnamese coastline. Those operations involved both Blue Water Navy and Brown Water Navy vessels.

Surface Gunfire Support

Another role of the Blue Water Navy was to supply surface gunfire support to ground troops in Vietnam. Gunfire support was provided primarily by cruisers and destroyers, which were stationed offshore within range of targets, fired for a period of hours or days, and then returned to safer locations farther offshore to reload ammunition and conduct repairs before rotating back onto the firing line. The ships often worked in teams to keep gunlines manned at all times. The committee heard from several navy veterans the gunline could be as close as one mile offshore, depending on such variables as how far inland the targets were, whether and to what extent they were experiencing enemy fire, and the range of their guns.

Logistics and Transport

Naval ships played a minor role in the transport of people and supplies from the US mainland to Vietnam. At the beginning of the war, there was some trans-Pacific troop transport on Navy ships, but most ground troops were arriving by commercial airline by the end of 1966. Navy ships did, however, transport some troops after their arrival in Vietnam. For example, amphibious transport dock ships, such as the Duluth, transported ground troops to the coastal waters of Vietnam; the troops would either travel to shore via smaller landing vessels or directly disembark to Vietnam if the ship docked (if the ship docked, sailors

aboard at the time would be considered brown-water sailors under current VA compensation regulations; see discussion later in this chapter).

Some Navy ships were tasked primarily with providing logistical support. Many auxiliary ships—including floating barracks and floating base platforms, hospital ships, gasoline tankers, and repair ships—regularly docked in bays or traveled the inland waters in Vietnam and so are not considered part of the Blue Water Navy.

The Brown Water Navy in the Vietnam War

A primary mission of the Brown Water Navy was to prevent the movement of supplies supporting the NLF along the rivers and coastal waters of South Vietnam. Weapons and people were often hidden by civilians in sampans (a common type of Vietnamese boat), and the job of the US sailors was to halt and inspect all suspicious craft. Brown-water boats patrolled inland waterways, deltas, and coastal areas day and night and also enforced the nightly curfew on boat traffic.

A second mission was combat. A coordinated combat unit with Army personnel, the Army-Navy Riverine Assault Force, sought out and attacked enemy combatants on and along waterways and delta areas.

Among the many Brown Water Navy operations were Operation Game Warden (1965–1970), which was an interdiction effort focused on the inland waterways of South Vietnam; Operation Market Time, which dealt with interdiction on the coast and included Blue Water Navy ships; and Operation SEALORDS (Southeast Asia Lake, Ocean, River, and Delta Strategy) in the Mekong Delta.

The living conditions of brown-water sailors differed from those of the blue water sailors. For example, brown-water sailors typically lived onshore in temporary barracks or tents and sometimes on their boats if no safe onshore accommodations were available.

Although accurate information on the number of naval personnel considered to be in the Brown Water Navy is not available, the Commander US Naval Forces Vietnam Monthly Historical Summary for October 1969 indicates that on a typical day in March 1969 there were 160 river assault craft in operation, including Vietnamese Marine Corps craft (available at: http://www.history.navy.mil/ar/docs/comnavforv/1969/October1969.pdf). Given the complement of men aboard each vessel type, that could mean that more than 1,000 sailors were engaged

in these operations, although this would not constitute the entire Brown Water Navy.

The Coast Guard in the Vietnam War

Over 8,000 Americans served in Vietnam as part of the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard operated under the authority of the Navy and served in five major categories of operations: preventing enemy and enemy-supply movement, port security, aids to navigation, ensuring the safe and efficient transport of supplies by merchant ships, and search and rescue. Some Coast Guard personnel served on small ships and boats that functioned as part of the Brown Water Navy; others served aboard larger ships, such as the high-endurance cutters, which had crews of around 100–150 men and were part of the Blue Water Navy fleet (Scotti, 2000). In the present report, the committee does not distinguish between Coast Guard and Navy sailors; the committee assumed that Coast Guard sailors would have the same exposure potentials as Blue Water Navy or Brown Water Navy sailors, depending on the types of activities they undertook and the types of ships or boats on which they served.

The Merchant Marine in the Vietnam War

During the Vietnam War, as in other wars, the US Merchant Marine functioned as an auxiliary of the Navy and transported supplies for the armed forces. Ships in the Merchant Marine are civilian owned and staffed by civilians, but Navy personnel were sometimes stationed aboard these ships. Merchant Marine vessels included both large oceangoing ships that took supplies across the Pacific from the United States or from Navy bases elsewhere in Asia, and smaller vessels that transported supplies upriver within Vietnam (American Merchant Marine at War, http://www.usmm.org/vietnam.html). Many materials, including herbicides, were shipped from the United States to Vietnam on civilian-manned Merchant Marine ships, not via Navy vessels. With the exception of some merchant seamen who served during World War II, members of the Merchant Marine are not recognized as military veterans and thus are not eligible for VA benefits (http://www.usmm.org/vietnam.html).

Land-Based Naval Operations in Vietnam

In South Vietnam, the Navy was active throughout the war in advising and training the South Vietnamese Navy. Navy personnel were also involved in humanitarian and morale-building campaigns. For example, hospital ships provided health care for the civilian South Vietnamese population both aboard ships and through outreach on land. The Seabees, the construction force of the Navy, lived ashore and constructed harbor facilities and engaged in other building projects. In general, these sailors experienced living conditions similar to those of noncombat personnel in the other services that were stationed in Vietnam on similar missions.

THE DEBATE OVER BLUE WATER NAVY EXPOSURE TO AGENT ORANGE

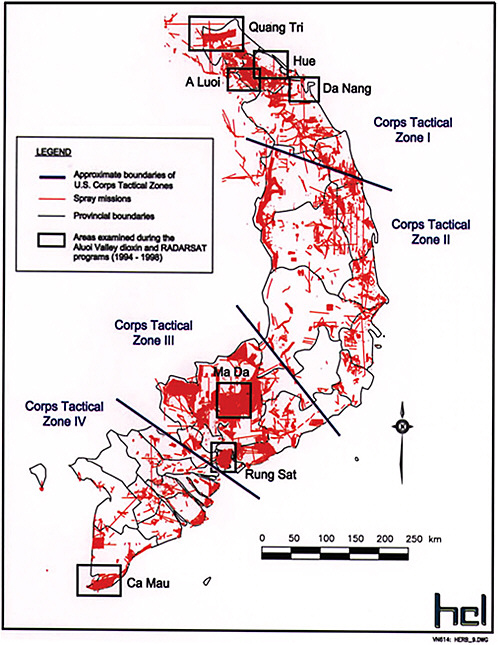

A variety of tactical herbicides were used by the American military in Vietnam during 1962–1971 to defoliate forests and destroy crops. Some of them, including the mixture known as Agent Orange, contained the highly toxic TCDD. The extent of herbicide spraying varied across the country, with some areas receiving far more extensive spraying than others. For example, during the Vietnam War the American military divided South Vietnam into four geographic zones (see Figure 2-1) and III Corps Area, which included the area around Saigon, was sprayed with more than twice as much herbicide as the other zones (IOM, 1994). (See Chapter 3 for more information on the herbicides, including the volumes sprayed in Vietnam.)

Agent Orange Legislation

By the middle 1950s, there was evidence from industrial exposures and accidents that the TCDD found in Agent Orange posed health risks for humans. During the Vietnam War, American scientists voiced concerns about possible health risks for American troops and the Vietnamese population, and the US government commissioned a series of studies on the issue in the mid- to late 1960s (Butler, 2005). On the basis of those studies, the United States in October 1969 began limiting its use of herbicides in Vietnam; spraying ceased entirely in 1971 (IOM, 1994).

FIGURE 2-1 Aerial herbicide spraying missions in southern Vietnam, 1965–1971.

SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from Hatfield Consulting, http://www.cc.gatech.edu/~tpilsch/AirOps/Images/RanchHand/Map-spray_msns-RVN-65-71.jpg (accessed February 22, 2011).

Additional concerns about the health risks posed to Vietnam veterans arose after the war. In the late 1970s, a Chicago benefits counselor in the Veterans’ Administration (now the Department of Veterans Affairs) began to suspect that Agent Orange was causing health problems in Vietnam veterans, and her testimony in the 1977 televised documentary Agent Orange: The Deadly Fog increased the general public’s and veterans’ awareness of the issue. In 1979, a class-action lawsuit was filed by veterans against several large chemical companies that had manufactured the herbicides used during the war. The case was settled out of court in 1984, and a settlement fund was established (Schuck, 1986).

Beginning in 1979, Congress enacted several laws to examine links between exposure to herbicides in Vietnam and possible long-term health effects. In 1984, Congress first required the VA to establish guidelines and standards for evaluating the scientific studies and to issue regulations for adjudicating claims for VA benefits based on herbicide exposure. In 1991, Public Law (PL) 102-4, the Agent Orange Act, was passed. It required VA to ask the IOM to conduct periodic reviews of the available scientific and medical evidence of health effects that followed exposure to the herbicides used in Vietnam, including Agent Orange and its contaminant TCDD. The law also stipulated that the IOM studies be conducted every 2 years for 10 years after publication of the initial report, which occurred in 1994. The Veteran Education and Benefits Expansion Act of 2001 (PL 107-103) extended the timeframe of the studies through 2014. Based on the eight biennial Veterans and Agent Orange (VAO) reports published to date that assessed the peer-reviewed literature on the health effects of exposure to herbicides, particularly Agent Orange and TCDD, the VA has identified 14 health conditions associated with Agent Orange exposure. For a discussion of those health effects, see Chapter 6 of the present report and the VAO report series.

The Blue Water Navy’s Exposure to Tactical Herbicides During the Vietnam War

As with any war, it is difficult or impossible for those serving in the conflicts to identify the many chemical agents to which they might have been exposed intentionally or unintentionally during active duty. Because of the impossibility that most Vietnam veterans could prove that they had been exposed to Agent Orange or other herbicides in Vietnam during the war, the 1991 act created a presumption of service connection;

that is, exposure to herbicides in Vietnam was presumed for any Vietnam veteran who became ill with a disease found to be associated with TCDD exposure. That presumption—a mechanism of disability compensation that the VA has used in other contexts—allows veterans to receive disability compensation and treatment for a medical condition without having to provide proof that the condition was “incurred in or aggravated by” their military service (38 USC 1116(a)(2)).

As the VA began to process applications for presumptive service connections for herbicide-related disabilities, it was forced to decide whether service in the waters off the coast of Vietnam satisfied the requirements of the statute for service in Vietnam. The statutory language defines eligibility as extending to veterans “who, during active military, naval, or air service, served in the Republic of Vietnam during the period beginning on January 9, 1962, and ending on May 7, 1975” (USC 1116 (a)(1)). The decision of whether blue water service constituted service in the Republic of Vietnam was not consistent for a number of years. One commonly used standard for service “in the Republic of Vietnam” was possession of a Vietnam Service Medal, which was given to members of the Blue Water Navy who served in or near Vietnamese waters as part of the war effort. In 1997, the VA held that “service on a deep-water naval vessel in waters off the shore of the Republic of Vietnam does not constitute ‘service in the Republic of Vietnam’ for purposes of 38 U.S.C. § 101(29)(A) (VA, 1997).” As a result of that precedent opinion, at least some Blue Water Navy veterans who received Vietnam Service Medals were denied claims.

Haas v. Peake

Attention to whether Blue Water Navy Vietnam veterans were or should be eligible for a presumptive service connection to herbicide exposure increased as a result of a challenge to the VA precedent opinion in the court case Haas v. Peake. In 2001, Blue Water Navy Vietnam veteran Jonathan Haas first sought a presumptive service connection from his VA regional office for type II diabetes. Haas had served on the ammunition ship USS Mount Katmai off the coast of Vietnam during August 1967–April 1969. He had never gone ashore, and his ship had never gone into port in Vietnam, but he claimed that the Mount Katmai had sailed as close as 100 ft from the Vietnamese coast and had been “engulfed by an Agent Orange cloud” and thus argued that he had been exposed (Haas v. Peake. 2008. Jonathan L. Haas, Claimant-Appellee v.

James B. Peake, Secretary of Veterans Affairs, Respondent-Appellant. 2007-7037. US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.). When his claim was denied, he appealed the regional office decision to the Board of Veterans’ Appeals, where it was again denied in 2004.

In denying his claim, the board in 2004 cited the regulatory language in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), which stated that “service in the Republic of Vietnam includes service in the waters offshore and service in other locations if the conditions of service involved duty or visitation in the Republic of Vietnam” (CFR Title 38, 3.307(a)4(iii)), and Haas had not served on the ground or on the inland waters. The court also stated in its decision that his claim was rejected because it was “unsupported by any evidence demonstrating that this ship was located in waters sprayed by herbicides.”

Haas again appealed, and this time the VA decision was reversed by the US Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims (Haas v. Nicholson. 2006. Jonathan L. Haas, Appellant v. R. James Nicholson, Secretary of Veterans Affairs, Appellee. No. 04-0491. United States Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims.). That court, known as the Veterans Court, found the VA’s interpretation of the regulatory language defining service in Vietnam as requiring service on inland waters or on Vietnamese soil to be unduly restrictive. The court also cited the VA’s history of granting presumptive service connections for members of the Blue Water Navy who had received Vietnam Service Medals and commented on the issue of whether exposure was possible:

Given the spraying of Agent Orange along the coastline and the wind borne effects of such spraying, it appears that these veterans serving on vessels in close proximity to land would have the same risk of exposure to the herbicide Agent Orange as veterans serving on adjacent land, or an even greater risk than that borne by those veterans who may have visited and set foot on the land of the Republic of Vietnam only briefly (Haas v. Nicholson. 2006. Jonathan L. Haas, Appellant v. R. James Nicholson, Secretary of Veterans Affairs, Appellee. No. 04-0491. United States Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims.).

The VA appealed the decision and in 2008, the Veterans Court decision was reversed, and the VA’s original decision to deny a presumption of service connection to Blue Water Navy veterans was upheld by the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (Haas v. Peake. 2008. Jonathan L. Haas, Claimant-Appellee v. James B. Peake,

Secretary of Veterans Affairs, Respondent-Appellant. 2007-7037. US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.). The US Court of Appeals found the VA’s interpretation of service in Vietnam to require visitation to land or travel on inland waterways to be permissible. The court did not find the decision to exclude Blue Water veterans to be arbitrary and concluded that because the VA general counsel’s interpretation of the regulatory language was “neither plainly erroneous nor inconsistent with the language of the regulation,” it deserved judicial deference by the appeals court (Haas v. Peake. May 8, 2008. Decision Assessment Document. No. 2007-7307. 2008. United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Court.).

During the appeal process for the Haas case, there was a court-ordered stay on processing Blue Water veterans’ claims, many of which had been made after the 2006 Veterans Court decision. After the final decision in 2008 (the Supreme Court declined to hear the case), the VA began processing the backlog of 17,000 claims, most of which were from Blue Water Navy Vietnam veterans. Although these veterans were not eligible for an automatic presumption, each case needed to be reviewed to determine whether a nonpresumptive service connection was justified or the veteran in question actually qualified for the presumption because his boat docked or entered Vietnamese inland waters while he was aboard.

Royal Australian Navy

The original Haas claim cited direct spraying and aerial drift of herbicides as possible routes of exposure for Blue Water Navy personnel off the coast of Vietnam. In the 2008 court proceedings, a new route of possible exposure was introduced: the ingestion of TCDD through contaminated potable water on Blue Water Navy ships. This claim was based on the results of a study commissioned by the Australian Department of Veterans Affairs in 2002 that suggested that the water-distillation process used aboard Australian Navy ships could result in increased concentrations of TCDD in the potable water made on the ship (Muller et al., 2002). That study had been prompted by the finding that mortality in Royal Australian Navy (RAN) veterans was higher than that in Australian veterans who served on the ground in Vietnam during the war (see Chapter 6 for a more detailed discussion of this epidemiologic study). On the basis of the epidemiologic results and the 2002 Australian distillation study, the Australian Department of Veterans Affairs decided

to provide disability compensation to its Vietnam naval veterans for medical conditions related to herbicide exposure.

The IOM committee that prepared the most recent VAO report (IOM, 2009) examined the validity of those findings and how they might relate to the potential for the US Navy water-distillation systems to concentrate TCDD and found them to be scientifically reasonable. Inasmuch as US Navy ships used the same distillation systems as the RAN, the committee concluded

No measurements of TCDD concentrations in seawater were collected during the Vietnam conflict, so it is not possible to ascertain the extent to which drinking water on US vessels may have been contaminated through distillation processes. However, it seems likely that vessels with such distillation processes that traveled near land or even at some distance from river deltas would periodically collect water that contained dioxin. Thus, a presumption of exposure of military personnel serving on those vessels is not unreasonable. (IOM, 2009)

The presence of TCDD in shipboard potable water requires the assumption that TCDD was present in the marine water used to distill the potable water. The Australian study cited accounts from Australian sailors who served on RAN ships, that the ships frequently drew marine water in or near the mouths of estuaries and river deltas to make potable water and used marine water from the open ocean to make distilled water to run the boilers; the boilers required far more distilled water than did the ships’ crews. Subsequent information received from the Australian Department of Veterans Affairs indicated that although RAN standard operating procedures required that, except in emergency circumstances, potable water was to be made only when 10 or more miles from populated shores, these procedures were not always followed and the reasons for doing so were not clear (Eileen Wilson, Australian Department of Veterans Affairs, personal communication, October 10, 2010). Four RAN ships provided support to US Navy ships on gunlines that could be located as close as 2.8 miles (4,572 meters) from the coast; the ships spent about one month on the gunline (Wilson et al., 2005a).

Current Status of Blue Water Navy Veterans’ Claims

VA continues to deny Blue Water Navy Vietnam veterans presumptions of service connections for herbicide-related conditions unless

for those Veterans who served aboard ships that docked and the Veteran went ashore, or served aboard ships that did not dock but the Veteran went ashore, their service involved “visitation” in Vietnam. In cases involving docking, the evidence must show that the Veteran was aboard at the time of docking and the Veteran must provide a statement of personally going ashore. In cases where shore docking did not occur, the evidence must show that the ship operated in Vietnam’s close coastal waters for extended periods, that members of the crew went ashore, or that smaller vessels from the ship went ashore regularly with supplies or personnel. In these cases, the Veteran must also provide a statement of personally going ashore. (VA, 1997)

The VA continues to develop a list of Blue Water Navy ships documented to have entered inland waters and the dates on which they did so. A ship that was in a deep-water harbor, for example, such as Da Nang, would not count as being in “brown water” (VA, 2008).

The largest Blue Water Navy ships, the aircraft carriers, rarely entered inland waters or came close enough to shore to dock due to their large size and vulnerability to enemy attack. Cruisers also were too large to enter inland waterways, although a few did enter some sections of rivers such as the Saigon and the Cua Viet. Smaller ship classes such as destroyers, destroyer escorts, minesweepers, survey ships, salvage ships, cargo and transport ships were capable of safely navigating some inland waterways and did so on occasion as part of their military missions. As of January 2011, over 140 individual ships and 51 classes of Navy vessels that served in the Seventh Fleet during the Vietnam era have been categorized as having served primarily or exclusively in inland waterways, temporarily in inland waterways, or in coastal waterways of Vietnam with evidence that crew members went ashore or that smaller ships regularly went ashore with supplies or personnel (James Sampsel, VA, personal communication, January 12, 2011).

Blue Water Vietnam veterans can still file claims for service-related disabilities, but their claims have to be reviewed case by case and

exposure to herbicides has to be demonstrated. Blue Water Navy veterans are eligible for compensation under a separate regulation for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Under 38 CFR 3.313, “service in Vietnam” includes service in waters offshore for the purposes of NHL compensation, because there is no claim of a link to herbicide exposure.

Underlying the controversy of Blue Water Navy Vietnam veterans’ claims to a presumption of herbicide exposure are the legal mandates to compensate veterans for their current health problems. Vietnam veterans who served on the ground and on the inland waterways of Vietnam are eligible for compensation for their health problems regardless of the time they spent in Vietnam and the potential for their exposure to the tactical herbicides, such as Agent Orange, that were widely used during the war.

REFERENCES

Appy, C. G. 1993. Working-class war: American combat soldiers & Vietnam. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Butler, D. A. 2005. Connections: The early history of scientific and medical research on “Agent Orange.” Journal of Law and Policy 13:527-552.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1994. Veterans and Agent Orange: Health effects of herbicides used in Vietnam. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2009. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2008. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Marolda, E. J. 1994. By sea, air, and land: An illustrated history of the U.S. Navy and the war in Southeast Asia. Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center.

Muller, J. F., C. Gaus, K. Bundred, V. Alberts, M. R. Moore, and K. Horsley. 2002. Examination of the potential exposure of Royal Australian Navy (RAN) personnel to polychlorinated dibenzo TCDDs and polychlorinated dibenzofurans via drinking water. A report to: The Department of Veteran Affairs, Australia. Brisbane, Australia: National Research Centre for Environmental Toxicology.

Schuck, P. H. 1986. Agent Orange on trial: Mass toxic disasters in the courts. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Scotti, P. C. 2000. Coast Guard action in Vietnam: Stories of those who served. Central Point, OR: Hellgate Press.

Turley, W. S. 2009. The second Indochina war: A concise political and military history, 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 1997. Service in the Republic of Vietnam for purposes of definition of Vietnam Era—38 U.S.C. § 101(29)(A). Memorandum from VA General Counsel to Director of Compensation and Pension Service. VAOPGCPREC 27-97. July 23, 1997.