5

EXPOSURE ROUTES AND MECHANISMS

This committee was tasked with comparing exposure among three military populations that served in Vietnam—troops on the ground, Brown Water Navy personnel, and Blue Water Navy personnel—to Agent Orange and its contaminant, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Several previous Institute of Medicine (IOM) committees refrained from attempting to make precise estimates of troop-level exposure, because of the lack of data on concentrations of herbicides and particularly of the contaminant TCDD in air, water, soil, and foodstuffs during the Vietnam War and because of a paucity of information on the location of troops in relation to the location of spraying (IOM, 1994, 2003, 2008). Those uncertainties are amplified for Navy personnel, on whom even less information is available.

Thus, the approach used by this committee was to evaluate possible pathways of exposure of each of the three populations (termed exposure opportunities) and to consider whether it is plausible that people in these groups could have been exposed via these pathways to Agent Orange–associated TCDD. The lack of environmental concentration data and the lack of sufficient data on ground troop and Navy personnel locations made it impossible to quantify exposure for either of these populations. Thus, any assessment of exposure must be qualitative, rather than quantitative. Assessments of exposure opportunities were supported by information on the fate and transport of TCDD (see Chapter 4) and the sparse documented information on potential pathways of exposure. The committee also considered anecdotal information (including presentations given at its meetings) from a variety of sources.

The committee considered the environmental fate and transport of Agent orange–associated TCDD from aerial and riverbank spraying in combination with activities of Navy personnel and ground troops, as described in Chapter 4, as its starting point for its assessment of exposure opportunity. In the most general terms, environmental distribution

processes, physical transport and dispersal, and degradation processes generally predict a concentration gradient for environmental herbicide and TCDD, with greater attenuation at greater distances from the points of introduction (spraying), except for processes that result in increasing concentrations, such as bioconcentration and distillation of marine water to make potable water on blue-water ships. It is therefore generally reasonable to suppose that the greatest exposure opportunities would be related to proximity to herbicide use and to locations with higher herbicide and TCDD contamination and that personnel who are at a distance from these locations would have lower exposures. Applying that general expectation to the circumstances and populations of interest has been the major thrust of the committee’s efforts to characterize exposure. Specifically, the committee used fate and transport considerations combined with professional judgment to produce estimates of potential exposure opportunities in the three populations.

A schematic of the movement of Agent Orange and TCDD from the point of application (from spraying of Agent Orange from aircraft, from trucks, or from boats) to marine waters and air was shown in Figure 4-1. Working from that schematic, the committee sought to identify the exposure routes likely to result in Agent Orange and Agent Orange–associated TCDD exposure opportunities in each of the military populations. It should be noted that there are Blue Water Navy personnel who qualify as Brown Water Navy personnel as a result of their ships’ locations or activities but have not yet been so designated by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), although they may be in the future. The committee did not consider the possible reclassification of those Blue Water Navy sailors in its exposure evaluations.

PREVIOUS EXPOSURE MODELING EFFORTS

Given their inability to quantify exposure of US military personnel to Agent Orange–associated TCDD, several prior IOM committees identified various approaches to approximate it. The IOM report The Utility of Proximity-Based Herbicide Exposure Assessment in Epidemiologic Studies of Vietnam Veterans (IOM, 2008) defined the simplest approach to characterizing herbicide exposure as being “based on a veteran’s presence or absence in Vietnam during the period of herbicide spraying.” At the second, more complex level, “measures of exposure ... are based on information on the location, timing, and volume

of herbicide spraying combined with information on the location in space and time of individuals or military units.” The measure might be refined at the third level by “incorporation of more detailed data or models for the fate and transport of herbicides in the environment, such as spray drift models, estimates of the proportion of the sprayed herbicide that reached the ground, or consideration of secondary transport of the herbicides or the TCDD contaminant in the environment.” The fourth and fifth levels, as defined by that committee, begin to assess exposure at the individual level and require exposure and pharmacokinetic data.

Exposure opportunity has been defined as the potential for exposure rather than as a quantitative determination of exposure (that is, relatable to dose) and is therefore only a crude estimate of dose (IOM, 2008). There are no environmental concentration data (for example, data on concentrations in soil and water) for the three populations of interest on which to base estimates of individual dose or exposure levels. Thus, the potential for exposure is the best—in fact, the only—available method for assessing and comparing exposure.

To assess Blue Water Navy exposure opportunity, the committee expanded on past IOM definitions of exposure opportunity (beyond proximity to sprayed areas defined by the Stellman model (Stellman et al., 2003) and beyond exposure opportunity immediately after herbicide application) to include exposure pathways relevant to Blue Water Navy personnel (for example, shipboard treated water and accidental contact from coastal spraying).

EXPOSURE PATHWAYS

In conducting an exposure assessment for a site with active contamination, the standard approach would be to collect samples of various media, such as soil and water, and analyze them for chemicals of interest. However, there is no longer the opportunity to collect such data for the environmental media in Vietnam because the contamination occurred so long ago and it is virtually impossible to extrapolate from back from current TCDD concentrations to concentrations that might have been present during the Vietnam War. Therefore, two alternative approaches were considered. The first was to quantify exposure of the three populations (on the basis of the sparse data available on ground troops and Navy personnel movements and estimates of possible herbicide exposure in light of fate and transport considerations) and then

compare ranges of exposure. Previous IOM committees (IOM, 2003, 2008) conducted exhaustive searches for sufficient information with which to conduct this type of assessment in connection with ground troops and concluded that such data were not available. The present committee sought data on the Blue Water Navy and similarly concluded that the necessary data are unavailable. Thus, the committee acknowledged the impossibility of this approach.

For the second approach, the committee determined that any assessment of exposure must be qualitative rather than quantitative. Qualitative estimates should be informed by knowledge of the fate and transport of the chemicals of interest and by documented or anecdotal information on potential pathways of exposure. The committee initially considered all potential exposure pathways, except spraying or other application and handling of herbicides, and then determined which of the potential routes could be considered plausible.

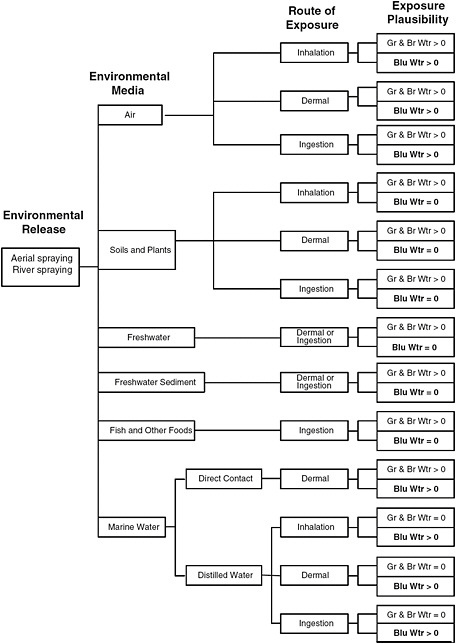

In the sections below, the committee examines the environmental pathways that could result in exposure of ground troops, Brown Water Navy personnel, and Blue Water Navy personnel to Agent Orange–associated TCDD from two major herbicide sources: aerial spraying and riverbank spraying. The committee discusses plausible pathways of exposure to TCDD in each environmental medium (air, soil and plants, freshwater, freshwater sediment, fish and other foods, and marine waters); determines whether each pathway can plausibly lead to Agent Orange–associated TCDD exposure; and presents the evidence on which the determination was based. Note that in the following sections, exposure of ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel is considered together; the committee found that there is insufficient information on personnel behaviors, environmental concentrations of TCDD, or other crucial aspects of exposure to draw distinctions between exposures for these two populations. Figure 5-1 presents the exposure pathways the committee found to be plausible for ground troops, and Brown Water Navy personnel, and Blue Water Navy personnel.

The committee recognized that in addition to possible differences in exposure potential among populations, there are differences among individuals. Even ground troops or Navy personnel with similar job descriptions would be expected to have experienced varied exposure because of differences in environmental concentrations, personal activities, and associated intake characteristics (such as exposure duration, food and water ingestion rates, inhalation rate, and body weight). The committee recognizes that there may be individuals in a

FIGURE 5-1 Exposure pathways for Agent Orange–associated TCDD.

NOTE: An exposure plausibility value of 0 indicates that this pathway is not considered to be plausible; a value of > 0 indicates that this pathway is considered to be plausible. Blu Wtr = Blue Water Navy personnel, Br Wtr = Brown Water Navy personnel, and Gr = ground troops.

given group whose experiences do not accord with the descriptions given in this report. It should be noted that ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel included an unknown fraction of personnel who were remote from spraying operations and possibly had no opportunity for exposure. However, the VA noted that the definition of ground troops who served in Vietnam for the purposes of presumption of “service relatedness” was deliberately crafted to include persons who had little or no likelihood of exposure to guarantee that all cases of exposure (in the face of large uncertainties) were included. Thus, for the purposes of this report, if exposure was plausible for any fraction of a population, the committee assumed plausibility of exposure of the population as a whole. In addition, the committee recognizes that even a qualitative assessment of plausible exposure opportunity is fraught with uncertainty because of a lack of data, nonharmonious recollections of activities and locations of activities, and the heterogeneity of activities within each population.

Exposure to Agent Orange–Associated TCDD from Releases to Air

Herbicide and herbicide components exist in airborne form as aerosols from sprayed applications, as vapors of volatilizable herbicide components released from aerosols or from treated surfaces, and as aerosols from contaminated surfaces (soils, oil slicks, and marine surfaces) because of wind or mechanical action. Inhalation and dermal routes of exposure are considered, as well as ingestion, which is a plausible exposure route when aerosols and particles that enter the mouth are swallowed.

Inhalation

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

There is some information on ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel on which to base conclusions regarding inhalation exposure plausibility (IOM, 2003, 2008). Although Young (2009) argues that ground troops were unlikely to be in or near areas of direct aerial spraying of herbicides, information on the distance between individual troops and the spray path is lacking. Given the possibility of spray drift of up to 7 km1, the committee could not reject the possibility that some ground troops had inhalation exposure to herbicide spray drift. Stellman reported that during March 1969, 72 of 278 companies of Army combat

battalions in III Corps Area were within 0.5 km of a spray path and had a potential for direct exposure to herbicide (IOM, 2008).

The General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office) (GAO, 1979, cited in IOM, 2008, p. 49) found that 5,900 of 218,000 Marines who served in 1966–1969 were within 0.5 km of a spray path on the day of spraying and 17,400 were within 2.5 km; this suggests a potential for inhalation of spray drift. Brown Water Navy missions included some spraying of riverbank foliage, so in at least some instances Navy personnel were required to operate close to herbicide application. The committee was unable to ascertain how often that occurred or what proportion of Brown Water Navy personnel might have participated.

Therefore, although the extant information, based on modeling efforts, reveals variability in the extent of area over which troops and personnel may have plausibly inhaled Agent Orange–associated TCDD, common sense dictates that inhalation exposure of ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel to Agent Orange spray drift or volatilized TCDD is plausible.1

Blue Water Navy personnel

The VA has determined that Blue Water Navy personnel do not have a presumption of exposure; this implies that their opportunity for herbicide exposure by aerial drift from spraying of herbicides in Vietnam was considered to be insignificant. The committee questioned that assumption. In the course of its deliberations, the committee was provided information indicating that many Blue Water Navy ships came relatively close to the Vietnamese shore, in some cases within 1 nautical mile of the coastline (RADM [retired] Joseph Carnevale, personal communication, June 9, 2010). Without data on the specific timing and location of each Operation Ranch Hand mission flown near the Vietnamese coastline and similar information on the timing and location of naval support missions, it is impossible to determine how many Blue Water Navy personnel might have been exposed to drift from aerial spraying and to what extent such exposure might have occurred near the coast. Maps of the Operation Ranch Hand missions, based on Herbicide Reporting System (HERBS) data, show that some flight paths were close to the South Vietnamese coast. In particular, there was heavy spraying in the III Corps Area near Saigon, including the mangrove swamps near the

coast. It is plausible that drift from near-coastal spraying extended over estuarine and marine waters under some environmental conditions.

Without information to the contrary, the committee finds that it is plausible, although probably rare, that such exposure occurred. Therefore, the opportunity for Blue Water Navy personnel to have experienced inhalation exposure by this route cannot be entirely discounted but would have been limited to instances when vessels were operating close to (within a few kilometers of) shore in locations where and at times when spraying occurred.

Another source of potential inhalation exposure to Agent Orange was reported by Blue Water Navy veterans. The committee heard and read several anecdotal reports from Blue Water Navy personnel indicating that they had been sprayed from aircraft passing directly overhead. The committee is uncertain how to interpret those reports given the lack of specifics regarding the spraying incidents, such as where the ship was at the time of the incident (how far off the coast and where along the coast) and whether the spray was Agent Orange or another fluid, such as diesel fuel or malathion.

Stellman et al. (2003) identified about 40 cases of herbicide dumping in the HERBS files. The committee estimated that perhaps four of them were near the Vietnamese coast. The committee received one 1969 report indicating that one such dump occurred 10 km offshore in the South China Sea off Bac Lieu province, but information on the date, circumstances, and amount of the herbicide dump is not available (Susan Belanger, personal communication, November 28, 2010). That province is in the extreme south of Vietnam in an area that was heavily sprayed throughout the war. The committee considers inhalation exposure via aerial dumping of herbicides to have been very rare.

Ingestion

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel might be expected to have some potential for ingestion of aerosols via inhalation followed by mucociliary transport and swallowing.

Blue Water Navy personnel

The committee could not rule out inhalation followed by mucociliary transport as a potential pathway of exposure of Blue Water Navy personnel who were aboard ships at sea.

Dermal

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

Direct deposition of herbicide spray onto any ground troops or Brown Water Navy personnel in the area of aerial spraying is possible and would be expected under conditions where there is substantial inhalation exposure opportunity. Young (2009) indicates that every effort was made to ensure that friendly ground troops were not in the vicinity of any of the Ranch Hand missions. Nevertheless, Stellman and Stellman (2004) indicate that some ground troops may have been in an area that could receive herbicide drift. Therefore, the committee concludes that some ground troops had the potential for direct dermal contact with herbicide-spray drift and could not rule out this pathway for Brown Water Navy personnel.

Blue Water Navy personnel

The committee’s reasoning about dermal exposure of Blue Water Navy personnel from aerial drift follows the same line as for inhalation exposure. The lack of data on the extent of aerial drift and the different drift scenarios proposed by Stellman and Stellman (2004) and by Ross and Ginevan (2007) led the committee to conclude that, as with inhalation exposure, some level of dermal exposure might be possible for personnel aboard Blue Water Navy ships that were near shore (within the drift deposition area) during Ranch Hand missions. Similarly, dermal contact would be plausible if Blue Water Navy personnel were exposed to spray directly or from herbicide dumps. The committee recognizes that such instances may be rare, but they cannot be discounted entirely without further, labor-intensive efforts to coordinate Ranch Hand mission flight paths with Blue Water Navy ship locations.

Exposure to Agent Orange–Associated TCDD from Soils and Plants

Among the several factors that must be considered in assessing potential exposure to Agent Orange–associated TCDD via contact with soil or plants are penetration of the plant canopy to soil, adsorption of TCDD on plants and soil surfaces, dust concentrations in the atmosphere, and atmospheric degradation of volatilized Agent Orange–associated TCDD. Those fate and transport factors are discussed in Chapter 4.

Inhalation

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

Where Agent Orange has been used, adherence of TCDD to soil particles (dust) is likely. Dust may enter the atmosphere as a result of wind action across soil surfaces and mechanical actions, such as the movement of people or vehicles along unpaved surfaces. Ranch Hand missions and other herbicide-spraying missions often included clearing foliage from along roadways, and it is likely that ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel inhaled dust if they entered a sprayed area before degradation of Agent Orange–associated TCDD occurred. Short-distance transport of contaminated dust can also occur, so even troops operating at some distance from the spray path might inhale the dust. Rain would act to remove dust particles from the air, and this would lead to the potential for additional contamination at some distance from the dust source as atmospheric washout.

Volatilization of TCDD from soil is possible, but the committee expects that only ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel that were close to sprayed areas were likely to inhale Agent Orange–associated TCDD because of the potential for atmospheric dispersal and degradation of TCDD after volatilization from soil.

Inhalation exposure of ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel could also have occurred as a result of the volatilization of Agent Orange–associated TCDD from plant surfaces (see Chapter 4) (Hornbuckle and Eisenreich, 1996; McLachlan et al., 2002), particularly as atmospheric temperatures rose through the day. Therefore, the committee determined that it is plausible that ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel would have some opportunity for inhalation exposure to TCDD after aerial herbicide spraying and Agent Orange deposition on plant surfaces and soils.

Blue Water Navy personnel

Although volatilization of TCDD from plant surfaces and soil is possible and could result in the atmospheric transport of the chemical, the committee believes that—given the potential for photodegradation, dust washout in rain, and dispersal over long distances—it is unlikely that Blue Water Navy personnel would be exposed to Agent Orange–associated TCDD via this mechanism and route of exposure.

Ingestion

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

Ground troops might be expected to have some potential for ingestion of contaminated soils as a result of hand-to-mouth activity and consumption of foodstuffs and water contaminated with dust and dirt. That expectation is based on the likelihood of poor personal hygiene for many ground troops who lacked access to clean water and the likelihood that the same people passed through dusty areas where the soil had been contaminated by herbicide spraying. Another plausible mechanism for ingestion of Agent Orange–associated TCDD sorbed to dust is similar to that for ingestion of contaminated air discussed earlier, that is, movement of contaminated dust from the airways to the oropharynx. The committee could not rule out similar pathways of exposure of Brown Water Navy personnel.

Blue Water Navy personnel

The committee could not identify a plausible exposure pathway for ingestion of contaminated soil by Blue Water Navy personnel who were aboard ships at sea.

Dermal

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

Direct contact of ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel with contaminated soil and sprayed foliage is possible. Dermal contact with contaminated soil is likely under circumstances similar to those of inhalation exposure to dust, that is, troops exposed to contaminated dust along roadways or other areas of exposed soil, to windblown dust, and possibly, for ground troops, from being obliged to lie on the soil for protection.

Ground troops in particular may come into contact with herbicide-sprayed vegetation, particularly if they enter a recently sprayed area. TCDD is known to adhere to the waxy surfaces of foliage (see Chapter 4). Ginevan et al. (2009) report that a conservative estimate of 20% of the amount of herbicide sprayed may be assumed to be available for transfer to human skin or clothing, but they also state that the bioavailability of TCDD on waxy leaf surfaces decreases rapidly, with a dissipation half-life of 1–3 days (Karch et al., 2004). Therefore, although it is difficult to determine how much TCDD is likely to transfer to ground troops entering a sprayed area within 3 days of spraying, such an

exposure mechanism cannot be ruled out. A similar exposure scenario may be assumed for Brown Water Navy personnel brushing against foliage along riverbanks that have been sprayed.

Blue Water Navy personnel

Blue Water Navy personnel would not be expected to come into direct or indirect contact with contaminated Vietnamese soils or foliage while aboard ships at sea. Therefore, the committee concluded that there is no potential for exposure to Agent Orange–associated TCDD for Blue Water Navy personnel via this exposure pathway and route.

Exposure to Agent Orange–Associated TCDD from Fresh Water

Vietnam has numerous large and small rivers, streams, lakes, and bays that are used for transportation, fishing, and other activities. The committee was provided information that indicated that flight paths often included the spraying of surfaces of streams and rivers (Jeanne Stellman, Columbia University, presentation to the committee, September 20, 2010). In addition, Brown Water Navy personnel sprayed riverbanks (Zumwalt, 1993). Direct deposition of herbicide spray and, to a smaller extent, contaminated dust and atmospheric washout and water runoff are sources of herbicide contamination of surface waters (see Chapter 4). The committee did not consider inhalation exposure to Agent Orange–associated TCDD from contaminated surface waters to be an important route of exposure for any of the populations considered here.

Ingestion

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

The committee was unable to locate information on water sources or water treatment of Vietnamese surface (or ground) water to determine the potential for TCDD contamination of freshwater supplies either on US military bases or from local municipal water supplies. The committee was also unable to locate specific information about sources of potable water for ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel. Westheider (2007) reported that water evaporators were used on some US military bases in Vietnam to produce potable water. Anecdotal information suggests that ground troops, particularly those who were in the field and away from firebases, would sometimes obtain their water from fast-running streams, rainwater, and shell holes in addition to carrying water canteens and rubber bladders (http://community.history.com/topic/10831/t/Usable-water.html).

Other information on water sources could not be identified. It is possible that some of the water sources had been sprayed with herbicide. Water treatment, if used, would probably be aimed at controlling pathogens and would not be expected to reduce TCDD contamination substantially other than by removal of settleable solids. Thus, exposure of the two populations to Agent Orange–associated TCDD via ingestion of freshwater is plausible.

Blue Water Navy personnel

Blue Water Navy ships generated their own potable water from marine water (discussed later) and therefore are not expected to have had the opportunity for exposure to potable water from Vietnamese freshwater sources. If a ship docked and took on potable water from Vietnam, crewmembers would have been eligible for a presumption of herbicide exposure only for the time the ship was docked (VA, 2008). Thus, exposure of this population to Agent Orange–associated TCDD via ingestion of freshwater was not considered to be plausible.

Dermal

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

Both ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel had opportunities to come into direct contact with contaminated surface waters while wading through streams or along riverbanks or by entering the waters to swim or for other activities, such as boat repair. Thus, this route of exposure is plausible.

Blue Water Navy personnel

Blue Water Navy personnel are not expected to have had the opportunity for dermal contact with fresh surface waters unless their ship docked in Vietnam and took on freshwater. In that situation, crewmembers would be eligible for a presumption of herbicide exposure for the duration of the ship’s docking.

Exposure to Agent Orange–Associated TCDD from Freshwater Sediment

The spraying of inland waters in Vietnam during the Operation Ranch Hand missions and reported riverbank spraying by Brown Water Navy personnel resulted in the contamination of surface waters. As described in Chapter 4, TCDD in water absorbs to organic material in the water and can be transported with the current or settle in sediment.

TCDD absorbed on soil particles could also enter the waterways via runoff from sprayed areas during rain or monsoons.

Ingestion

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel might be expected to have some potential for ingestion of contaminated sediments as a result of consumption of water that contained sediments. Hand-to-mouth activity may also result in ingestion where hygiene is poor.

Blue Water Navy personnel

Blue Water Navy personnel are not expected to have had opportunities for exposure to freshwater sediments in the inland waters of Vietnam.

Dermal

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

As in the case of exposure to contaminated surface waters, ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel may have had the opportunity for direct contact with contaminated sediments when walking along riverbanks, wading across streams, or engaged in other activities in inland waters, such as swimming. Because sediments can be transported for some distance in water with a strong current, it is possible that military personnel were exposed to TCDD-contaminated sediments even when they were not near sprayed areas.

Blue Water Navy personnel

Blue Water Navy personnel are not expected to have had opportunities for exposure to freshwater sediments in the inland waters of Vietnam.

Exposure to Agent Orange–Associated TCDD from Fish and Other Foods

Most human exposure to TCDD via food comes from the consumption of contaminated animal products, such as meat, fish, and dairy. Animals may eat contaminated forage, such as grasses, and bioaccumulate TCDD in their fatty tissues (IOM, 2003). Although TCDD is poorly translocated in plants (Zhang et al., 2009) and TCDD that adheres to plant surfaces typically does not move to other plant

parts, animals and humans may consume TCDD in contaminated soil particles that adhere to the plants if they are not thoroughly cleaned before consumption. Fish are also likely to bioaccumulate TCDD from water via ingestion of contaminated organic matter (Rifkin and Lakind, 1991; Chiao et al., 1994).

Ingestion

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

The opportunity for exposure to TCDD-contaminated food varied considerably among military personnel stationed in Vietnam. Reports indicate that much of the food of US military personnel stationed on larger bases was obtained from the United States as rations. Westheider (2007) states that “at base camps, soldiers ate a variety of foods, from steak and potatoes washed down with beer to Vietnamese dishes in local eateries.” Other military personnel, particularly Army soldiers and Marines, were issued or otherwise had available C rations. US Air Force and Navy personnel most often had access to dining facilities that served a greater variety of food, including A rations.

Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol rations contained freeze-dried foods (http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Food_available_at_the_vietnam_war). Food in the field included a variety of dehydrated and canned meals or fish, rice, and food obtained from the vicinity. Field kitchens would serve B rations, 1-gal cans of food prepared by Army cooks in the field (Westheider, 2007).

US Navy riverine forces would have consumed C rations while patrolling the rivers in their boats (http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/vietnam/trenches/weapons.html).

TCDD concentrations in the food obtained from the United States is expected to be the same as would be experienced by the majority of the US population. The committee was unable to obtain any measurements of the TCDD content of local Vietnamese foods during the war. Because local foods were consumed and some local foods may have been derived from crops grown in areas that had been sprayed with herbicides or derived from animals that had grazed on herbicide-sprayed crops, the committee could not rule out consumption of food as a pathway for exposure of the two populations to Agent Orange–associated TCDD.

Blue Water Navy personnel

Blue Water Navy ships did not take on rations of Vietnamese food but relied on rations of US food or food from other locations, such as

Subic Bay, Philippines. Thus, they would not have had the opportunity for Agent Orange–associated TCDD exposure via ingestion of contaminated foods. The committee was informed that the Blue Water Navy ships rarely or never obtained food from Vietnam. That is consistent with the information received by the committee during its public session on the USS Midway regarding the operation of the larger ships, such as aircraft carriers, but the committee was unable to determine whether there might have been exceptions among smaller ships that operated in coastal marine waters. Blue Water Navy personnel on ships that docked in Vietnam to take on food, including Vietnamese food, would meet the criteria for a presumption of herbicide exposure if they stated they went ashore while the ship was docked.

The committee heard conflicting reports on whether fishing from Blue Water Navy ships occurred. Some indicated that there was occasional fishing and consumption of the fish caught. Others indicated that fishing from their ships was nonexistent. In the absence of data beyond the testimony on fishing and fish-consumption practices, such an exposure mechanism cannot be ruled out, although the amount of TCDD consumed by eating contaminated marine fish is likely to be very small.

Exposure to Agent Orange–Associated TCDD from Marine Water

The concentrations of TCDD in the marine waters surrounding Vietnam during the war have been the subject of much debate and considerable speculation. No contemporaneous measurements of TCDD in marine waters or sediments were identified by the committee. As discussed in Chapter 4 and the Appendix, TCDD tends to adsorb on organic matter in water; thus, freshwater that contains suspended organic matter and enters marine systems from areas that were treated with herbicides is likely to have contained Agent Orange–associated TCDD. Contamination of marine waters by direct application or discharge of Agent Orange is also a possible scenario. Records of spraying of Agent Orange over marine waters as part of Operation Ranch Hand have not been identified. The committee did not examine all the HERBS files to determine whether any of the Ranch Hand missions sprayed herbicides intentionally or accidentally over marine waters. However, some of the flight paths, such as those over the Rung Sat area, appear to have extended to coastal waters, albeit for only short distances. There are rare reports of Ranch Hand aircraft dumping herbicide over coastal waters (10 km offshore), as noted earlier. Moreover, the committee heard and

read several anecdotal reports of aircraft spraying over marine waters. The committee was unable to locate any confirmed reports of Agent Orange spraying over marine waters.

The committee considered that some direct contact of all the military populations stationed in and around South Vietnam with TCDD-contaminated marine water was possible. The only plausible route of exposure to TCDD in marine waters is dermal contact. On the basis of the best professional judgment, the committee did not consider exposure via contaminated marine water by ingestion or inhalation as plausible. The exception is the use of distilled marine water as potable water on Blue Water Navy ships; this is discussed separately below.

Dermal Contact

Ground troops and Brown Water Navy personnel

There are numerous pictures of American troops in marine waters—for example, at China Beach—during the war (for example, http://www.wardogs.com/vcbcbl.html). Those personnel may have been exposed to Agent Orange–associated TCDD by swimming or wading in contaminated waters. Although no specific information on Brown Water Navy personnel was available, they might have been exposed to Agent Orange–associated TCDD in marine waters if they were operating near the mouth of a river that was contaminated or if their ship moved from brown water to blue water and they were in contact with the water.

Blue Water Navy personnel

The committee was told that personnel on larger ships operating off the coast did not engage in marine swimming, but it was within the discretion of the commanding officer of each ship to permit it. The committee heard anecdotal reports of occasional swim calls on some smaller Blue Water Navy ships. The committee was told that such calls were infrequent because of the dangers associated with sharks and sea snakes in the South China Sea. Therefore, although the committee found it plausible that Blue Water Navy personnel may have had occasional direct dermal contact with contaminated marine waters from swimming or spray (during heavy seas), such contact was expected to be infrequent and of short duration.

Distilled Potable Water

Blue Water Navy personnel

Large Blue Water Navy ships—such as aircraft carriers, cruisers, and destroyers—generated their own potable-water supply for use in ships’ boilers and secondarily for crew uses, such as drinking, food preparation, bathing, and cleaning. Potable water is produced by distillation of marine water. Although the marine water passed through a sieve to remove large debris such as seaweed, the water was not further filtered or treated before it entered the ship’s distillation plant. The use of shipboard distillation plants is discussed in more detail in the Appendix. As a matter of policy, production of potable water from polluted marine waters, such as estuaries and harbors or when ships are traveling in close formation, was avoided (NAVMED P-5010-6) (Department of the Navy, 1990). Section 2.4.2, “Polluted Water” of the Naval Ships’ Technical Manual, states that

unless determined otherwise, water in harbors, rivers, inlets, bays, landlocked waters, and the open sea within 12 miles of the entrance to these waterways, shall be considered to be polluted.... The desalting of polluted harbor water or seawater for human consumption shall be avoided except in emergencies.

The committee was unable to determine whether this regulation was in effect during the Vietnam War but was told by several retired naval officers that it was the practice at that time, although exceptions did occur. The committee received information from several Blue Water Navy veterans that firing lines for US ships could be as close to the Vietnamese coastline as 1–2 nautical miles. Although ships did not stay on the firing line for long periods, it is possible that they sometimes took up water for distillation while relatively close to the coastline.

The issue of distillation of marine water is important because of the finding by the committee that prepared the 2008 Veterans and Agent Orange update (IOM, 2008) that Blue Water Navy veterans could have been exposed to TCDD via contaminated potable water. As noted in that report and discussed in the Appendix to the present report, the Australian Department of Veterans Affairs determined that Royal Australian Navy personnel who served offshore were exposed to TCDD from herbicide spraying in Vietnam because the distillation systems onboard the ships were thought to be able to increase the concentration of TCDD in potable water during the evaporative process compared with the TCDD

concentration in the source water (Muller et al., 2001). In the Appendix, a theoretical model is applied to a batch distillation model by using physical constants of TCDD to corroborate the findings of the experimental Australian study that found substantial codistillation of contaminants during production of potable water with a batch distillation unit. The findings of the theoretical model agreed with the findings of the Australian study that codistillation was probable during distillation of contaminated water. Therefore, high contaminant concentrations in source water could be magnified during the distillation process. If Agent Orange–associated TCDD was present in the marine water, potable water was a plausible route of exposure.

As presented in Chapter 4, the committee found that Agent Orange–associated TCDD could, under some circumstances, contaminate marine waters off the coast of South Vietnam. Blue Water Navy ships may have distilled those marine waters, so TCDD contamination of potable water aboard those ships was possible. Use of potable water containing Agent Orange–associated TCDD could result in inhalation exposure to TCDDs in water vapor during showering or other uses of hot water, such as cooking, and could result in volatilization of TCDD from the water during other uses, such as cleaning. Use of the water for showering and cleaning would also result in dermal exposure to TCDDs. Finally, the use of the potable water for drinking itself and for food preparation could lead to ingestion of TCDD. Questions about the engineering systems used to produce potable water on Blue Water Navy ships and their effect on concentrations or enrichment of Agent Orange–associated TCDD increase the uncertainty in the importance of this exposure route.

CONCLUSIONS

The committee identified several plausible exposure pathways and routes of exposure to Agent Orange–associated TCDD in the three populations, including Blue Water Navy personnel (see Figure 5-1). Plausible pathways and routes of exposure of Blue Water Navy personnel to Agent Orange–associated TCDD include inhalation and dermal contact with aerosols from spraying operations that occurred at or near the coast when Blue Water Navy ships were nearby, contact with marine water, and uses of distilled water prepared from marine water.

The committee cannot provide quantitative estimates of exposure by any of the exposure pathways described above because of lack of data on

environmental concentrations of TCDD and activity patterns of military personnel. At best, the committee can judge whether specific routes of exposure are plausible.

REFERENCES

Chiao, F. F., R. C. Currie, and T. E. McKone. 1994. Intermedia transfer factors for contaminants found at hazardous waste sites: 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Davis, CA: University of California, Davis.

Department of the Army. 1971. Field manual: Tactical employment of herbicides. Washington, DC: Headquarters. December.

Department of the Navy. 1990. Chapter 533, Potable Water Systems. Navy ships’ technical manual. NAVMED P-5010-6. Washington, DC: Naval Sea Systems Command.

Ginevan, M. E., J. H. Ross, and D. K. Watkins. 2009. Assessing exposure to allied ground troops in the Vietnam War: A comparison of AgDRIFT and Exposure Opportunity Index models. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology 19(2):187-200.

Hornbuckle, K. C., and S. J. Eisenreich. 1996. Dynamics of gaseous semivolatile organic compounds in a terrestrial ecosystem—Effects of diurnal and seasonal climate variations. Atmospheric Environment 30:3935-3945.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1994. Veterans and Agent Orange: Health effects of herbicides used in Vietnam. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003. Characterizing exposure of veterans to Agent Orange and other herbicides used in Vietnam. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2008. The utility of proximity-based herbicide exposure assessment in epidemiologic studies of Vietnam veterans. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Karch, N. J., D. K. Watkins, A. L. Young, and M. E. Ginevan. 2004. Environmental fate of TCDD and Agent Orange and bioavailability to troops in Vietnam. Organohalogen Compounds 66.

McLachlan, M. S., G. Czub, and F. Wania. 2002. The influence of vertical sorbed phase transport on the fate of organic chemicals in surface soils. Environmental Science & Technology 36(22):4860-4867.

Muller, J. F., C. Gaus, K. Bundred, V. Alberts, M. R. Moore, and K. Horsley. 2002. Examination of the potential exposure of Royal Australian Navy (RAN) personnel to polychlorinated dibenzodioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans via drinking water. A report to: The Department of Veteran Affairs, Australia. Brisbane, Australia: National Research Centre for Environmental Toxicology.

Rifkin, E., and J. Lakind. 1991. Dioxin bioaccumulation: Key to a sound risk assessment methodology. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health 33(1):103-112.

Ross, J., and M. Ginevan. 2007. Points for the committee to consider when evaluating the Stellman model. Presentation to the IOM Committee on Making the Best Use of the Agent Orange Exposure Reconstruction Model. May 1.

Stellman, S. D., and J. M. Stellman. 2004. Exposure opportunity models for Agent Orange, dioxin, and other military herbicides used in Vietnam, 1961-1971. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology 14(4):354-362.

Stellman, J. M., S. D. Stellman, R. Christian, T. Weber, and C. Tomasallo. 2003. The extent and patterns of usage of Agent Orange and other herbicides in Vietnam. Nature 422(6933):681-687.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2008. Further definition of Vietnam “Blue Water” versus “Brown Water” service for the purpose of determining Agent Orange exposure. Compensation & Pension Service Bulletin p. 2-3. December.

Westheider, J. E. 2007. The Vietnam War. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Young, A. L. 2009. The history, use, disposition and environmental fate of Agent Orange. New York, NY: Springer.

Zhang, H., J. Chen, Y. Ni, Q. Zhang, and L Zhao. 2009. Uptake by roots and translocation to shoots of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in typical crop plants. Chemosphere 76(6):740-746.

Zumwalt, E. R. 1993. Letter to the Institute of Medicine Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides regarding draft version of the IOM chapter on the U.S. military and the herbicide program in Vietnam, May 20, 1993.