CHAPTER TWO

A Conceptual Framework for Resilience-Focused Private–Public Collaborative Networks

The committee’s charge included the development of a framework for private–public collaboration to enhance community disaster resilience. Any single template or checklist would not sufficiently address the full array of needs for collaboration of all communities around the country or the diverse threats they face. The committee therefore sought to develop an overarching conceptual framework that would provide the context in which collaborative efforts are best undertaken. The framework laid out in this chapter focuses on organizational aspects of encouraging and enabling private–public collaboration and on the processes and strategies for institutionalizing effective communitywide collaboration. To create the framework, the committee explored theoretical concepts and models and related literature. The resulting conceptual model is the basis of the specific guidelines and examples provided later in this report.

Three themes are presented in this chapter. The first is the theoretical necessity for private–public collaboration focused on building community resilience. The committee describes the assumptions on which its theoretical framework is based, discusses the role of collaboration in comprehensive emergency management and capacity building, and explains what disaster resilience means for a community. The second theme is the theoretical basis for successful collaboration. The chapter delves into concepts such as creating incentives, planning perspectives, and the advantages of decentralized decision making processes. Levels of engagement are also addressed. The final theme is the committee’s conceptual model for resilience-focused private–public collaboration and describes the elements therein. Organizational aspects of the framework will be presented in Chapter 3.

BASIC PRINCIPLES THAT SHAPE THE CONCEPTUAL FRAME

The overarching conceptual frame that guides this report is derived from research in several disaster-related disciplines and from guidance the committee received at its workshop (NRC, 2010). The framework rests on the following assumptions:

-

Disaster resilience correlates strongly with community resilience, including economic, environmental, health, and social-justice factors.

-

Private–public collaboration is based on collaborative relationships in which two or more private and public entities pool and coordinate the use of complementary resources through the joint pursuit of common objectives.

-

Effective collaboration ideally encompasses the full fabric of the community and is representative of all walks of life—including minorities, the impoverished or disenfranchised, children, and the elderly—so a community-engagement approach is essential for the success of resilience-focused collaboration.

-

Principles of comprehensive emergency management, incorporating an all-hazards approach, guide resilience-focused collaboration-building efforts.

The framework adopted by the committee assumes that disaster resilience is closely linked with broader capacity-building strategies aimed at long-term community and environmental sustainability. The relationship between disaster resilience and sustainability is directly proportional: communities that suffer high losses in disasters are often the ones that have paid little attention to overall sustainability issues, and communities that actively plan for a more sustainable future are more likely to achieve disaster resilience. Thus, resilience-focused collaboration is likely to be most effective when integrated with and built on broader community functions, including those associated with public health and safety, economic viability, housing quality, infrastructure development, and environmental quality. As multiple workshop participants noted, community resilience involves more than disaster response (NRC, 2010).

Why Collaborate?

Scholarship focusing on the evolution of institutional forms emphasizes that such activities as the production and delivery of goods and services are seldom undertaken by single large corporations or by vast government bureaucracies. Rather, various parties that own or manage different types of resources work in concert to produce and provide goods and services.

The same societal trends influence efforts related to disaster-loss reduction. Taking an example from the homeland security arena, the Department of Homeland Security has a statutory responsibility to protect the critical infrastructure of the United States, but much

critical infrastructure is owned and managed by private entities.1 Protection can be achieved through collaboration among government and private entities. At the city and county levels, various public agencies—such as local emergency-management agencies and police, fire, and emergency medical services agencies—each have specific response-related roles, but they cannot meet their objectives alone. Reliance on broad participation by private entities—such as private hospitals, debris-removal contractors, the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, other nonprofit entities that provide aid to disaster victims, and privately owned utilities—is essential.

Public policy scholars also note that collaborative approaches are invariably needed to address large, complex problems, particularly ones that can be categorized as “wicked problems” (e.g., Rittel and Webber, 1973; Rayner, 2006). Wicked problems have several characteristics: they are extremely complex, people who offer solutions often disagree, it is difficult to address different aspects of these types of problems incrementally because they are tightly interwoven, and they are never solved “once and for all.” Analysts note that wicked problems are often intractable because the parties that should provide solutions are often the ones that helped create the problems. The scale and complexity of wicked problems demand collaboration among agencies, organizations, sectors, jurisdictions, and disciplines and fields of expertise. Examples of wicked problems are those associated with climate change, homeland security, and disaster reduction.

Although organizations increasingly rely on collaboration to achieve their goals and tackle wicked problems, collaborators are still independent actors who generally cannot be compelled to work with one another. Instead, potential partners interact, learn about one another, and weigh the costs and benefits of affiliating with other parties before agreeing to work together. Appropriate forms of governance for their collaborative activities can then be developed.

Businesses and other private-sector organizations are the foundation of the U.S. economy. Critical infrastructure providers include those that provide lifeline services such as power, water, and natural gas, as well as those that provide banking and financial services, information technology and telecommunication services, transportation, food and agricultural services, and health care services. Communities in the United States could not function without those services. Success in providing those services—and the success of many private-sector organizations more generally—often depends on the efficiency of the logistics and supply chain management. Large and small businesses and organizations that represent business interests have therefore become critical elements in the community social fabric. Collaboration with nongovernment organizations (NGOs) and private voluntary and faith-based organizations enables government agencies to build capacity. All elements

of the private sector are equal partners in successful community resilience-building efforts because of their function in every community.

The need for private–public collaboration relates directly to the evolution of governance in the United States and around the world. Contemporary developed societies are diverse, complex, and to a large extent information-driven, and they are much different from the bureaucracies and hierarchies that characterized the industrial age (Agranoff and McGuire, 2003). They require societal institutions that work compatibly and collaboratively. Outsourcing and contracting by government agencies have become common in the provision of government services; these practices bring together actors from the private and public sectors in complex relationships. Fast-moving economic and technologic processes require businesses to be flexible in forming alliances and joint ventures (Moynihan, 2005). Collaboration is essential for the provision of all types of goods and services and for the common welfare, including community disaster resilience.

Collaborative arrangements emerge because of the recognition that individual and collective goals are more likely to be achieved through collaborative rather than independent efforts. Collaboration is founded on trusted relationships, information sharing, incentives, and common goals, so facilitating and sustaining effective collaboration is challenging in a “command-and-control” environment. Benefits of collaboration are widely documented, and there is a substantial literature on collaborative management (e.g., McGuire, 2006), public administration (e.g., Vigoda, 2002), and collaborative emergency management (e.g., Waugh and Streib, 2006). The committee finds that the principles and approaches developed in such fields are vitally important to shaping resilience-enhancing collaboration, strategies, and goals.

Collaboration for Comprehensive Emergency Management

The committee considered literature on community engagement strategies and processes, including scholarship in such fields as public health and environmental protection. Lessons learned in those and related disciplines have implications for disaster-loss reduction. Under the principles of comprehensive emergency management, collaboration may focus on building community-level resilience to all types of disruptive events, from those most likely to occur to the rare, worst-case scenarios. The committee recognizes that particular types of hazards—such as pandemic influenza, bioterrorism, and chemical hazards—may require specialized capabilities and the development of specialized collaborative networks within networks. But the committee takes the position that communities prepared for the most common disruptions are also more likely to adapt in the face of more unusual threats. At the same time, the committee advocates for specialized planning by those communities with known unusual but identifiable risks—for example, risks associated with proximity to nuclear or chemical facilities.

The committee also concludes that a collaborative framework that addresses challenges across the full hazards cycle—from pre-event mitigation measures through efforts aimed at long-term recovery—is most likely to succeed at building resilience. It recognizes that not every community can take on all stages of disaster management and some may focus on one or two elements of the hazards cycle. It is important, however, to recognize how all the stages of the disaster cycle are linked and to plan accordingly.

Collaboration and Capacity Building

Private–public sector collaboration is an essential component of building capacity in communities. Collaborative relationships often begin with local organizers who have identified specific community needs. The process continues by mobilizing key leaders and relevant stakeholders in the community. Communication strategies and mechanisms that enable information sharing are critical to expanding collaboration to the broader community. Training programs in the use of communication tools may be useful to the organizers, as well as training on how to facilitate communitywide collaboration.

Community in the Context of Disaster Resilience

Effective resilience-focused collaborative networks are representative of the communities they serve, but they can also be coordinated with individuals and organizations outside the community. Ideally, collaboration includes representatives from local, state, and federal agencies; small and large businesses; nonprofit and faith-based organizations; academicians, researchers, and educational institutions; the mass media; civic and neighborhood organizations; technical experts; volunteers; and other diverse community stakeholders. The wealthy and the poor, the politically influential and those who are not, and both majority and minority populations would likewise be engaged. Identifying the critical points of contact for all constituencies in the community makes communication and outreach most effective. Doing so helps identify and mobilize the different perspectives and capabilities needed to address challenges fully and provide resources for building capacity.

Specific resources may not be available in some communities, and this confirms the importance of extending the reach of community beyond jurisdictional or geographic boundaries. When a community needs specific resources, collaborative networks may expand to incorporate regional stakeholders to fill the gaps. Disasters ignore jurisdictional and geographic boundaries, so communities will benefit by looking beyond such boundaries when building community disaster resilience.

Disaster management is a holistic function that cannot be successful if it does not engage the full fabric of the community. William Waugh, an emergency-management expert, testified before a subcommittee of the House of Representatives that the national

emergency-management system is made up of the local emergency-management offices, response agencies, and faith-based and other community organizations and that it is essential to engage these networks of private, public, and nonprofit organizations (Waugh, 2007). He also noted that the surge capacity during emergencies is often provided by ad hoc volunteer groups and individual volunteers:

We have a long history of volunteerism in emergency management in the United States and should always expect that volunteers will be a significant segment of our disaster response operations. Most fire departments today are still volunteer organizations. Most search and rescue is done by neighbors, family members, and friends. Faith-based and secular community groups increasingly have their own disaster relief organizations and the capabilities of those organizations are increasing rapidly. The point is that we have a system in place for dealing with large and small disasters that is heavily reliant upon local resources and local capacities.

The United States has long been a nation in which people and groups mobilize on a voluntary basis to achieve community objectives. Benjamin Franklin, for example, acted on his belief that voluntary cooperative action was good for the community when he established the first volunteer fire departments, public lending libraries, and fire insurance companies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Heffner, 2001). His writing may have influenced others, such as Alexis de Tocqueville, who wrote in the early 1830s of formal and informal associations that provide the context for citizens to participate in their communities. The principles that undergird citizen involvement and collaboration are the same as those that form the foundation of democracy itself (Pickeral, 2005). Collaborative networks are tools for involving the full fabric of the community and, by doing so, make disaster resilience easier to achieve.

DEFINING DISASTER RESILIENCE IN TERMS OF COMMUNITY RESILIENCE

A community becomes more disaster resilient through a conscious effort to do so. Community disaster resilience is best achieved through broad efforts that address economic, social, and environmental issues; disaster resilience is seldom achieved independent of broader community interests. To optimize community disaster resilience, however, it is essential for community stakeholders to form a common understanding of what community disaster resilience comprises. In this section of the report, the committee describes the relationship between community disaster resilience and community resilience, and how this relationship may be leveraged through private–public collaboration.

There is little empirical evidence to show that communities that incorporate general capacity-building strategies, including those to enhance social capital, into community planning strategies are in a better position to withstand disasters than their counterparts.

Research in areas related to social capital and economics, however, indicates that social capital is vitally important to organization performance (e.g. Burt, 2000). In an organization or group of organizations, networking and social capital control who has access to what information and when that information can be used advantageously. The committee extends this relationship to communities and performance during and following disaster. A well-connected community may be in a better position to share information to be used in crisis situations with its stakeholders. Strategically doing so will likely improve its stakeholders’ resilience. Communities recognize the value of collaboration for capacity building for a variety of purposes and are characterized by robust and active engagement between civil-society, government, and private-sector organizations. Participants in the committee’s information-gathering workshop stressed this concept. Disaster resilience is a byproduct of more general activities designed to improve the social and economic well-being of community residents. Being prepared for and surviving adversity are prerequisites of a healthy community. Ron Carlee, former manager of Arlington County, Virginia, and currently chief operating officer and director of strategic initiatives at the International City/County Management Association, emphasized during the committee’s workshop that “resiliency is not just for disaster … we need to build functional communities that provide quality of life everyday” (see Box 2.1).

Disaster-resilient communities, as a normal part of community functioning, prepare and plan to respond to and recover from disasters that are most likely to occur. Response and recovery take into account and benefit from the full fabric of the community, engaging

|

BOX 2.1 Resilience: Not Just for Disasters Communities that are factionalized, divisive, and suspicious of public and private institutions as a matter of routine are not likely to become models of collaboration during a disaster. Communities that have the best potential for achieving disaster resilience

SOURCE: R. Carlee, Arlington County, Presentation to the Workshop on Private–Public Sector Collaboration to Enhance Community Disaster Resilience, Sept. 10, 2010. |

all elements of the population in efforts to increase resilience. They are led by residents, organizations, and community partners that work collectively to achieve resilience and that identify and connect the networks and systems relevant to the resilience goals. As outlined in the National Response Framework (FEMA, 2008), local communities are ultimately responsible for managing hazards and disasters, and that responsibility requires the engagement of all community stakeholders in the private and public sectors, and faith-based organizations and NGOs (FEMA, 2008). Although leadership and incentives from the state and national levels may help communities to become disaster-resilient, community resilience is more sustainable when it is pursued from the ground up, is locally led and managed, and includes the full fabric of the community.

MOBILIZING A COMMUNITY TOWARD RESILIENCE

Numerous challenges confront efforts to create disaster-resilient communities. In disadvantaged communities or during perilous economic times, daily survival often takes precedence over planning for low-probability natural disasters. The contrasting impacts of the 2010 earthquakes in Haiti and Chile make vivid the importance of building resilience (see Box 2.2). The scale of devastation in Haiti was far greater than in Chile, in large part because of the level of advance preparation for a known risk.

A community-organization approach may be a means of successfully mobilizing communities toward resilience. Minkler and Wallerstein (1999:30) define community organiz-

|

BOX 2.2 Earthquakes in Haiti and Chile The 2010 earthquakes in Haiti and Chile illustrate how disaster preparedness can alter the outcome of similar catastrophic events. The earthquake and resulting tsunamis in Chile, although severe, were not unusual for the region, which has experienced 13 earthquakes of magnitude 7.0 or greater since 1973. The country was relatively well prepared for the event. In contrast, the people of Haiti were largely unaware of earthquake risks—the region last experienced a major earthquake in 1860—and poverty, poor building design and construction, and a lack of building standards led to the huge losses suffered in that country. Both earthquakes affected approximately 1.8 million people; however, although the power of the earthquake in Haiti (magnitude 7.0) was much lower than that in Chile (magnitude 8.8), the loss of life in Haiti was far greater. An estimated 222,000 deaths resulted from the Haiti earthquake, as opposed to 521 in Chile. SOURCE: USGS (2010). |

ing as “a process by which community groups are helped to identify common problems or goals, mobilize resources, and in other ways develop and implement strategies for reaching the goals they collectively have set.” Claudia Albano, a community advocate for the City of Oakland, California, defined community organizing as an approach that enables people, working together, to advance the cause of social justice.2 She noted four community-organizing goals that contribute to the enhancement of community resilience, especially in communities that have other pressing issues: win concrete improvements in people’s lives, empower people to speak and act effectively on their own behalf, effect institutional change, and develop an effective organization that wields the power of the community. Flexibility needed for sustainability can be partially achieved by allowing communities to determine their own priorities in addressing disaster and other community issues.

PRINCIPLES FOR SUCCESSFUL RESILIENCE-FOCUSED COLLABORATION

Previous sections of this chapter discussed the theoretical necessity of resilience-focused collaboration. This section begins the work of describing the theoretical basis for successful collaboration itself.

Identify and Create Incentives

Mandates and regulations are often seen by governments as the means to overcome barriers to collaboration and to provide incentives. For example, the 1986 Superfund Amendments3 required communities to establish local emergency-planning committees consisting of representatives of chemical companies, public-safety agencies, and other organizations to protect the communities from the consequences of hazardous and toxic chemical contamination. Such legal requirements run the risk of forcing mere compliance or engendering only token, as opposed to substantive, collaboration. That point was discussed by participants in the committee’s information-gathering workshop, especially in response to a presentation by Emily Walker regarding recommendations of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (also known as the 9-11 Commission)4 for national standards for emergency preparedness and the establishment of an accreditation and certification program for business disaster resilience (NRC, 2010). American communities are extremely diverse in many dimensions, including population, geography, economic drivers, social and cultural factors, political climate, and civic infrastructure. This

|

2 |

C. Albano, City of Oakland, Presentation to the committee, October 19, 2009. |

|

3 |

See www.epa.gov/superfund/policy/sara.htm (accessed March 12, 2010). |

|

4 |

See www.9-11commission.gov/ (accessed June 9, 2010). |

tremendous variation warrants caution against mandating or prescribing a single approach to resilience-focused collaboration.

To start, collaboration succeeds when value is demonstrated and incentives are provided to participants in reaching communitywide goals. In commercial enterprise, the effect on the bottom line and return on investment are important incentives, but so is the ability to build trusted networks, to ensure better coordination with other community stakeholders, and to access information that enables accurate risk and benefit analyses and more effective business continuity planning. Participation may serve as good public relations for an organization, resulting in greater recognition of the organization’s leadership in the community. As emphasized 45 years ago by economist Mancur Olson (1965), providing incentives for collaboration is especially challenging when collaborative activities aim at providing such public goods as environmental amenities, environmental quality in general, public health and safety, and disaster protection. Those are benefits that can be enjoyed in the future, even by those not involved in the efforts to achieve or preserve them. Incentives are essential to overcome tendencies of populations to let someone else solve problems.

Efforts to create collaboration focused on generating public goods often center on providing “selective incentives” that may be enjoyed only by those who agree to collaborate. Incentives that reduce the cost of joining collaborative relationships can be effective in overcoming “free riding,” but the committee notes that what motivates small-business owner participation may not constitute a successful incentive for a faith-based organization or a branch office of a major corporation. Different strategies need to be devised to encourage participation of the full fabric of the community, including potential nondisaster-related benefits.

Ultimately, many participants will be motivated by enlightened self-interest, business continuity concerns, and the desire to serve the public good. Encouraging stakeholders to ask themselves questions such as What will happen if we don’t plan for a disaster? and Can we afford to not have the ‘insurance’ that investment in resilience provides? may help guide them toward enlightened self-interest and participation in resilience-focused private–public collaboration.

Adopt an Appropriate Planning Perspective

The goals of collaboration will necessarily vary among communities because of differences in community priorities, vulnerabilities, culture, and resources. It is therefore impossible to design one model for collaboration that will be successful in all communities. Collaboration will most likely be successful if community resilience goals acknowledge the importance of identifying in advance the needs that will rise during each phase of the disaster cycle. Success of resilience-focused collaboration depends on planning in advance for disaster response and recovery. Adopting an appropriate planning perspective requires

systematic identification of the resources and strategies needed to accommodate land-use planning, public preparedness education, and short- and long-term disaster recovery for likely scenarios. Flexibility in planning is vital because disasters do not follow plans. Incorporating flexibility into collaborative efforts will also allow communities to deal with unexpected disasters because networks and resources will already be in place. Although flexibility is a vital component of successful collaboration—and for resilience in general—collaborative relationships are more effective and sustainable if not created “on the fly” when a disaster occurs. On-the-fly relationships do not benefit from systematic planning and the bonds of trust such planning creates.

Agree on Decentralized vs. Centralized Decision Making

The capacity of communities to build disaster resilience is tied to how and how well all members of the community—individuals and organizations—engage in collaboration and benefit from outcomes. In the formative stages of collaboration, decisions that determine the roles and responsibilities of different participants in collaborative efforts are made. Forming, maintaining, and sustaining effective cross-sector relationships and implementing activities that are decided collectively are daunting but not impossible challenges. Centralized and decentralized organizational collaboration for disaster resilience present different merits.

Studies of real-world partnering activities have provided some insight into how collaboration can be organized, but there is no current research on disaster resilience-focused collaboration. Evaluations of communities involved in Project Impact (see Box 1.2) provide some information regarding effective organizational models for disaster resilience-focused collaboration. For example, the Disaster Research Center (DRC) at the University of Delaware evaluated seven Project Impact pilot communities and their networks with an emphasis on organizational and decision-making structures (e.g., Wachtendorf et al., 2002a). The evaluation found that local pilot programs exhibited varied centralized and decentralized decision-making structures and a variety of organizational structures, ranging from horizontal to hierarchic. The DRC also studied nonpilot Project Impact communities. In one study involving 10 communities of different sizes, the communities’ organizational structures tended to be hierarchic and centralized, even though they organized their activities differently. That approach appeared to contribute to success in sustaining momentum in the period of time studied (Wachtendorf, 2002b).

The DRC stressed that most of the structures evolved—in response to goals, needs, and resources—into centralized structures (Wachtendorf, 2002a). Reports on those aspects of the program stressed that different organizational forms have both advantages and disadvantages. For example, tightly centralized collaborative structures offer the potential for better accountability, but they may also discourage innovation. The structure of Project

Impact networks also tended to shift as a consequence of project maturation, changes in focus, and mergers with other programs.

The committee recognizes that Project Impact was a short-lived program, and therefore the long-term benefits of one organizational structure over another cannot be determined from the evaluation of Project Impact communities. Additionally, Project Impact funding was provided to support a coordinating function in communities—some communities chose a hierarchical and centralized mechanism. Because a mechanism functioned for a period of time, and even functioned well, does not imply it was the “best” mechanism for that purpose or that it was sustainable. Given that, the committee turned to other sources of information on centralized versus decentralized approaches. For example:

-

Economists have done much research related to optimizing incentives within organizations. Ján Zábojník studied the costs associated with centralized decision making (Zábojník, 2002). His research indicates that it could be more cost effective for an organization to allow its employees to decide the methods for doing their jobs—even if managers have better information—than it is to motivate employees to accept methods proscribed top-down. Employee morale is a factor in his calculations.

-

In his examination of lessons learned from the private sector and U.S. Coast Guard responses to Hurricane Katrina, Steven Horwitz suggests that agencies with more decentralized structures (for example, the U.S. Coast Guard) were able to perform better following Hurricane Katrina than their more centralized counterparts in large part because they were more knowledgeable of the communities they were serving and because their decision making structure allowed them to respond more quickly to community needs. (Horwitz, 2008).

-

In his discussion of organizational characteristics critical for successful disaster response, John Harrald described essential elements of organizing for and coordinating response to extreme events including a combination of discipline (in structure, doctrine, and process) and agility (in the ability to be creative, improvise, and adapt) (Harrald, 2006). Harrald describes research by several social scientists that confirms the necessity of adaptability, creativity, and improvisation in disaster response; that such is more likely in an environment where organizational learning and decision making are decentralized is possible.

Much of the literature reviewed by the committee described how organizations worked or had the potential to work together during disaster response, for example in response to Hurricane Katrina. Those examples strongly suggest that decentralized decision making within a structure is effective in disaster response. Whereas these examples are useful, they do not discuss how best to organize private–public collaboration during normal, nondisaster

times, as encouraged in this report. Thus the nondisaster-related literature became important. The committee then considered relevant research literature, input received during its information-gathering workshop, and committee expertise. The committee concluded that an approach that emphasizes decentralized decision making and horizontal networks of collaborators—rather than top-down interactions between people and organizations—within a consensus-derived structural organization is best suited to achieving resilience goals. That conclusion was reached for several reasons. The horizontal network is the form of organization most compatible with the concept of collaboration. Just as collaborative arrangements aim at achieving goals once addressed by bureaucracies, networks can perform functions once performed by hierarchies. Although some may argue that centralization allows faster decision making and action, centralized organizations may be less effective in extremely stressful situations (e.g., Dynes, 2000). They have also been observed to be dependent on the skills, knowledge, and even personality of a core coordinator (Wachtendorf et al., 2002a).

In a related vein, network forms of organization are similar to the structure of the federal U.S. system of governance. Federalism is a decentralized form of governance that recognizes that different levels of government have distinctive resources and authorities and that public agencies at national, regional, state, and local levels develop their own distinctive types of collaborative arrangements.

Decentralized network arrangements are consistent with the growing importance of information as a force in contemporary societies and are well suited to information sharing in an “information society” that places a premium on knowledge management. Networks are increasingly prominent because of how societies and economies are organized. They are also consistent with the intent of the National Response Framework, which envisions a decentralized approach to disaster management and acknowledges local communities as the first line of defense when disasters strike. To consider decentralized decision making in collaborative arrangements and networks as a means of achieving resilience goals is therefore logical. The notion is further supported in the case of disaster management, in which gaining an awareness of local vulnerabilities, needs, and resources is paramount.

The committee cannot overstate the importance of community stakeholder agreement on the structure of collaboration and on decision-making processes before disaster strikes. Without agreement and “buy in” from the community on exactly how decisions will be made within the collaborative network, decisions—especially those made under stressful circumstances—may be met with resistance or distrust.

Allow for Multiple Levels of Engagement

Collaboration may occur in different forms and include different levels of engagement. It may occur through simple networking, through resource coordination, through information sharing, and through formal structural relationships. Simple networking requires

the least commitment on the part of participants, and thus the least investment and risk, because organizations retain separate resources and authority. It involves only intermittent exchange of information, common awareness and understanding, and a common base of support (Butterfoss, 2007). More complex forms of networking may incorporate networking tools that allow systematic and sophisticated information exchange. Relationships are generally without clearly defined structure or mission but may involve cooperation on specific tasks. Entities may cooperate for any number of reasons, such as sharing information and avoiding duplication of effort.

Complex goals established for mutual benefit among participants require a greater degree of coordination between individuals or organizations and may result in more formal and longer-term relationships focused on specific tasks. Resources and rewards may be shared, but each organization retains separate resources and authority. The highest level of collaboration may include new structural arrangements and commitment to a common mission among all participants. Such arrangements are sometimes called partnerships or coalitions. Resources may be jointly secured or pooled, and results and rewards are shared. Power may or may not be equally shared, but all members generally have input into collaborative processes. Higher-level relationship such as these will not work unless trust and productivity levels are high.

Building community resilience involves sustained effort at all levels of collaboration. Different individuals, groups, and organizations contribute at different levels at any given time. The level of engagement in collaboration is contingent on willingness both to commit and to risk more in the interest of community resilience on the basis of perceived benefits to participants. As the level of engagement increases, linkages between organizations become more intense and more influenced by common goals, decisions, and rules and by resources participants make available. According to Winer and Ray (1994), collaboration changes the way organizations work together. Organizations move from competing to building consensus; from working alone to including others from diverse cultures, fields, and settings; from thinking mostly about activities, services, and programs to looking for complex, integrated interventions; and from focusing on short-term accomplishments to broad systems changes.

THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL

Conceptual models allow the user to visualize system elements and their relationships. In the same way a roadmap represents routes from one location to another, a conceptual model simplifies and abstracts a real-world system, depicts the probable causal relationships between system components, and helps to identify the true relationship between seemingly independent system elements (Sloman, 2005). Conceptual models are encouraged as a starting point for planning, for example, by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in its guidance related to identifying and selecting evidence-based interventions (Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, 2009).

Strengthening community resilience through private–public engagement requires a conceptual framework that captures the unique characteristics of private–public collaboration. The committee developed a conceptual model for resilience-enhancing collaboration based on a community coalition action theory (CCAT) model for public-health applications developed by Butterfoss and Kegler (2002). Much of CCAT was borrowed from the fields of community development, community organization, citizen participation, community empowerment, political science, interorganizational relations, and group process (Butterfoss, 2007). Like the CCAT, the committee’s model provides a theoretical basis for initiating, maintaining, and establishing as an accepted part of the culture the complex collaborative relationships needed to create disaster-resilient communities. The model is intended to be used by both practitioners (those focused primarily on community outcomes) and researchers (those interested in looking at individual model elements empirically).

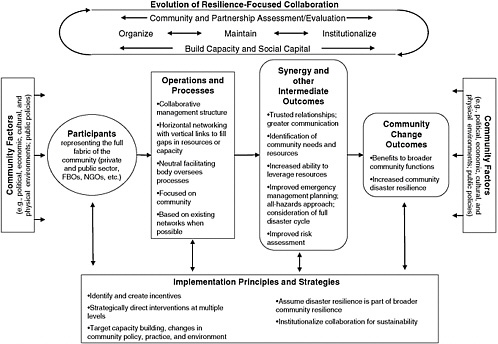

The conceptual model (Figure 2.1) first considers how resilience-focused collaboration is formed so that it will be effective and sustainable. On the basis of input the committee received during its workshop and firsthand experience of committee members, sustainable collaboration is more likely if it is based on a bottom-up approach and acceptance of the need for collaboration. A realistic assessment of the community is necessary to identify the common issues, resources, and capacities that may be leveraged to greatest advantage to build resilience. Evaluating existing networks is an important part of the assessment (Milward and Provan, 2006). Methods and models for collaboration appropriate for the community may then be chosen that allow flexibility and creativity, but also include a neutral facilitating body to oversee collaborative activities, seek funding, and have other day-to-day operational roles. Once the structure is chosen and established, consistent effort is needed to make sure that the structure remains an accepted part of “doing community business.” Collaboration itself is then best developed in stages that are revisited as new partners are recruited, plans are renewed, and missions, goals, and objectives are amended. Such tasks as recruiting and mobilizing members, refining the organizational structure, securing funding, building capacity, selecting and implementing strategies, evaluating outcomes, and refining strategies are best considered part of the normal functioning of collaborative efforts to ensure effectiveness and sustainability.

A conceptual model that accommodates the evolving and complex nature of comprehensive emergency-management systems is essential for developing resilience-focused collaboration, and the model has elements that can be applied to any collaborative network at any stage of development. Whereas disasters are common occurrences around the world, disasters in a given community can be high-consequence but low-probability events. Resilience-building collaboration requires constant maintenance to be effective. Regular assess-

ment of the extent to which collaborative activities can or do result in favorable community change is a vital component of the committee’s framework. Assessment of the collaborative structure, mission, objectives, and activities to maintain community relevance aids in the maintenance of collaboration and its acceptance by social institutions. Interdependences between critical infrastructure and networks need to be identified to create efficiency in the community (NRC, 2010). Interdependence and networking models will be effective if they are representative of current conditions, so regular reassessment is important. For those reasons, it is essential to understand, respond to, and even predict changes in the community in response to urbanization, shifting population densities, changing political administrations, and numerous other factors.

When assessing an existing collaborative network, organizers and participants may consider asking whether a bottom-up approach that ensures local-level acceptance and ownership in the scope and mission of the organization has been used. The assessment could also include such questions as: Did collaboration reflect the array of issues that represented the community’s concerns and interests? Are resources and capacities of the community understood so they can be leveraged to greatest advantage to build resilience? Are creative and flexible approaches applied in developing local resilience-building strategies? The conceptual model may help organizers determine the correct questions to ask, as well as determine the answers to the questions. Those forming new resilience-focused collaborative structures can be guided by the conceptual model and a comparable set of questions.

Allowing collaboration to evolve in response to findings from regular assessments makes sustainability more likely. Because sustainability is more than a measure of financial stability, as noted during the committee’s information-gathering workshop (NRC, 2010), assessments will be most useful if they measure sustainability of relationships in addition to financial and programmatic sustainability.

Model Components

The conceptual model (Figure 2.1) consists of six major nonlinear or sequential elements:

-

Community factors. These are the external factors that constitute the input to planning during all stages of collaboration, such as jurisdictional challenges, the political climate, public policies, communication and trust between different levels of government or between agencies, and liability concerns. Other similar issues are geography, access to resources, current levels of community disaster readiness, trust of organized networks by the community, and understanding of terminology and jargon (Magsino, 2009). These are all factors that can affect participation in

-

collaboration and the effectiveness of collaborative activities. Many of the factors, such as public policy, can themselves be influenced by collaborative action.

-

Participants. Sustainable and effective resilience-focused collaboration depends on representation of the full fabric of the community. Private–public collaboration implies engagement between government entities; diverse industry sectors; NGOs, including faith-based, voluntary, and citizen organizations; and other elements of the community. The ability or inability of collaboration to respond to a threat is often decided by the composition of its members and their agency affiliations. According to workshop participants, failure to include the full fabric of the community, especially disenfranchised groups, can lead to an ineffective collaboration (NRC, 2010). A community-engagement approach uses strategies necessary to ensure that collaborators are equally vested in achieving collaboration goals. Other factors that contribute to successful recruitment and engagement of collaborators are the experience of members with the issue of concern and the involvement of community gatekeepers and members of groups that are diverse in their expertise, constituencies, sectors, perspectives, and background (Butterfoss, 2007).

-

Implementation principles and strategies. A common understanding that disaster resilience is a part of broader community resilience is essential. Resilience-focused collaboration is successful when based on common goals and missions. Effective collaboration supports action strategies based on the resources and capacities available to the community. Efficient strategies are designed so that they are scalable and transferable to other collaborative and community efforts, regardless of the initial specific purpose. Interventions are more likely to build resilience if they include the entire community and if they are directed to different populations of the community in meaningful ways. Strategies to build capacity in all parts of the community to effect change in community policies, practice, and the environment are essential as are incentives to encourage and sustain participation in collaboration and community response to collaboration. Consideration of the sustainability of collaboration is vital in strategy planning. Sustainability is more likely if an understanding of the need for building resilience—and the need for private–public collaboration—is engendered in the community. Much as the business sector accepts the Chamber of Commerce as advocates for business concerns in the community, resilience-focused private–public collaborative structures will more likely be successful if accepted as advocates for overall community welfare.

-

Operations and processes. These include the collaborative management structure, the various horizontal and vertical networking links within the structure, and a neutral convening or facilitating body to help organize collaborative activities and other day-to-day functions of collaboration, including recruiting and mobilizing members, securing funds, building capacity, selecting and implementing strategies,

-

evaluating outcomes, and refining strategies. Collaboration and leadership models are best when chosen on the basis of the needs and character of the community. An important role of leadership is breaking down or rendering more permeable any “silos” of interaction within networks that inhibit common cause, such as the emergency-management community working independently of the private sector. Processes to manage conflict appropriately; to weigh the costs and benefits of continuing participation, planning, and resources development; and to identify, save, and leverage community resources are all very important to success. Networks need not be built from scratch; efficiency is enhanced by recognition and incorporation of existing effective community organizational networks when feasible and consistent with collectively agreed on missions and goals. Careful design of collaboration structure and processes allows effective recruiting, capacity building, mobilization, securing of funding, selection and implementation strategies, evaluation of outcomes, and refinement of strategies to ensure effectiveness and sustainability.

-

Synergy and other intermediate outcomes. Intermediate outcomes are beneficial results of the collaborative process, but not necessarily the final desired outcomes. They are the synergies created between organizations as a result of increased communication and trust, identification of community needs and resources, increased ability to leverage community resources for the good of the community, improved ability to assess community risks, and improved emergency and community management and planning. Stronger bonds between the private and public sectors are a result of collaboration. Those bonds will probably result in more effective assessment, planning, and implementation of all manner of community strategies (not just those for disaster resilience) and in tangible and intangible support and increased social networking within the community. With effective private–public collaboration comes an increased ability to resolve conflict within the community, a greater sense of belonging to the community, and a shared sense of local community ownership and responsibility among community members. The concept of collaboration synergy is predicated on the notion that individuals and organizations working together will accomplish more than could be accomplished by individuals separately.

-

Community change outcomes resulting in increased capacity and community disaster resilience. These are changes in the community that increase community disaster resilience, such as changes in community policies, practice, and environment that result from enhanced community capacity and participation. Greater community resilience is evidenced by community organizations that can more effectively prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters.

The nonlinearity of the model reflects the need for constant reassessment of the community and of the collaborative structure, goals, and strategies. As the community changes,

it is in the community’s best interest to reassess collaboration principles and strategies. This in turn triggers the necessity to evaluate the makeup of collaborating participants and the productivity of collaborative operations and processes. Peer mentoring—tapping into the expertise in other communities that have collaborated successfully—can be a valuable process for obtaining information on effective operations, processes, and strategies.

Much of the evidence supporting the validity of this conceptual framework and its guiding principles is anecdotal, and further examination of guidelines associated with the conceptual model is warranted. The conceptual model can be used by researchers as a roadmap to study and verify the systematic or logical connections of its elements, and determine, for example, metrics needed to assess the validity or progress of specific activities or outcomes. Ultimately, communities will adapt the framework according to their unique characteristics and locally determined issues and priorities. According to Mileti (1999: 63-64), “the process of transforming the future requires open-minded debate; full public participation; a willingness to experiment, learn, fine-tune, and alter; and a consensus among stakeholders to stand behind their shared commitment to the goal.” That concept applies directly to communities attempting to build resilience as they identify and resolve gaps in knowledge and practice.

Chapter 3 of this report provides guidance on applying the concepts in the committee’s conceptual model for private–public collaboration for enhancing community disaster resilience.

REFERENCES

Agranoff, R., and M. McGuire. 2003. Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Burt, R. 2000. The Network of Social Capital. In Research in Organizational Behavior, R. Sutton and B. Staw, eds. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, pp. 345-423.

Butterfoss, F. D. 2007. Coalitions and Partnerships in Community Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Butterfoss, F. D., and Kegler, M. C. 2002. Toward a comprehensive understanding of community coalitions: moving from practice to theory. In Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research, eds. R. J. DiClemente, R. A. Crosby, and M. C. Kegler. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, pp. 157-193.

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. 2009. Identifying and Selecting Evidence-Based Interventions Revised Guidance Document for the Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grant Program. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 09-4205. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at prevention.samhsa.gov/evidencebased/evidencebased.pdf (accessed September 7, 2010).

DHS (Department of Homeland Security). 2009. National Infrastructure Protection Plan: Partnering to Enhance Protection and Resiliency. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Homeland Security. Available at www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/NIPP_Plan.pdf (accessed August 5, 2010).

Dynes, R. R. 2000. Government Systems for Disaster Management. Preliminary Paper No. 300. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Disaster Research Center. Available at dspace.udel.edu:8080/dspace/bitstream/handle/19716/672/PP300.pdf;jsessionid=571354606BF18BE02F43A1A1702831D1?sequence=1 (accessed September 8, 2010).

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). 2008. National Response Framework. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Available at www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nrf/nrf-core.pdf (accessed March 11, 2010).

Harrald, J. R. 2006. Agility and Discipline: Critical Success Factors for Disaster Response. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 604(1): 256-272.

Heffner, R. C., ed. 2001. Democracy in America. New York: Penguin Books Ltd.

Horwitz, S. 2008. Making Hurricane Response More Effective: Lessons from the Private Sector and the Coast Guard during Katrina. Mercatus Policy Series, Policy Comment No. 17. Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Available at mercatus.org/uploadedFiles/Mercatus/Publications/PDF_20080319_MakingHurricaneReponseEffective.pdf (accessed September 8, 2010).

Magsino, S. 2009. Applications of Social Network Analysis for Building Community Disaster Resilience: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

McGuire, M. 2006. Collaborative Public Management: Assessing What We Know and How We Know It. Public Administration Review 66(1): 33-43.

Mileti, D. S. 1999. Disasters by Design: A Reassessment of Natural Hazards in the United States. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press.

Milward, H. B. and Provan, K. G. 2006. A Manager’s Guide to Choosing and Using Collaborative Networks. Networks and Partnerships Series. Washington, DC: The IBM Center for the Business of Government.. Available at www.businessofgovernment.org/sites/default/files/CollaborativeNetworks.pdf (accessed September 2, 2010).

Minkler, M., and N. Wallerstein. 1999. Improving health through community organization and community building: A health education perspective. In Community Organizing and Community Building for Health, ed. M. Minkler. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Moynihan, D. 2005. Leveraging Collaborative Networks in Infrequent Emergency Situations. Washington, DC: IBM Center for the Business of Government.

NRC (National Research Council). 2010. Private–public Sector Collaboration to Enhance Community Disaster Resilience: A Workshop Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Olson, M. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pickeral, T. 2005. Coalition Building and Democratic Principles. Service-Learning Network 11(1). Spring 2005 Constitutional Rights Foundation USA, Los Angeles, CA.

Rayner, S. 2006. Wicked Problems, Clumsy Solutions: Diagnoses and Prescriptions for Environmental Ills. Jack Beale Memorial Lecture on the Global Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. July 25. Available at www.ies.unsw.edu.au/events/jackBeale.htm (accessed March 12, 2010).

Rittel, H., and M. Webber. 1973. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences 4:155-169. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Inc.: Amsterdam.

Sloman, S. A. 2005. Causal Models: How People Think about the World and its Alternatives. New York: Oxford University Press.

TISP (The Infrastructure Security Partnership). 2006. Regional Disaster Resilience: A Guide for Developing an Action Plan. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers. Available at www.tisp.org/tisp/file/rdr_guide[1].pdf (accessed March 12, 2010).

USGS (United States Geological Survey). 2010. 2010 Significant Earthquake and News Headlines Archive. Available at earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eqinthenews/ (accessed September 16, 2010).

Vigoda, E. 2002. From responsiveness to collaboration: Governance, citizens, and the next generation of public administration. Public Administration Review 62(5): 527-540.

Wachtendorf, T., R. Connell, B. Monahan, and K. J. Tierney. 2002a. Disaster Resistant Communities Initiative: Assessment of Ten Non-pilot Communities. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Disaster Research Center Final Project Report #48. Available at dspace.udel.edu:8080/dspace/handle/19716/1158 (accessed June 21, 2010).

Wachtendorf, T., R. Connell, K. Tierney, and K. Kompanik. 2002b. Disaster Resistant Communities Initiative: Assessment of the Pilot Phase—Year 3. Newark, DE: University of Delaware. Available at dspace.udel.edu:8080/dspace/handle/19716/1159 (accessed March 12, 2010).

Waugh, W. L. 2007. Testimony before the Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management, House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. September 11. Available at republicans.transportation.house.gov/Media/File/Testimony/EDPB/9-11-07-Waugh.pdf (accessed March 12, 2010).

Waugh, W. L., and G. Strieb. 2006. Collaboration and leadership for effective emergency management. Public Administration Review 66(1):131-140.

Winer, M., and K. Ray. 1994. Collaboration Handbook: Creating, Sustaining and Enjoying the Journey. Saint Paul, MN: Amherst H. Wilder Foundation.

Zábojník, J. 2002. Centralized and Decentralized Decision Making in Organizations. Journal of Labor Economics. 20(1): 1-22.