The persistent, seasonal reoccurrence of a large area of hypoxic (oxygen-deficient) water in the northern Gulf of Mexico (NGOM) is a prominent, national-level nonpoint source water pollution issue. These hypoxic waters are caused by excess nutrient loadings from the Atchafalaya and Mississippi rivers into the Gulf (USEPA, 2007). Across the river basin, excess nutrient levels lead to noxious algal blooms that impair aquatic and drinking water systems. Nutrient-related pollution and its effects on drinking water supplies are of increasing concern. For example, in the nation’s public drinking water systems from 1998-2008, “nitrate exceedances showed a significant increasing trend, nearly doubling the number of violations” (USEPA, 2009). There has been only limited progress to date in developing sustained, effective national programs for addressing excess nutrients and water quality impairments, and this type of example indicates that the nation is losing ground to these problems.

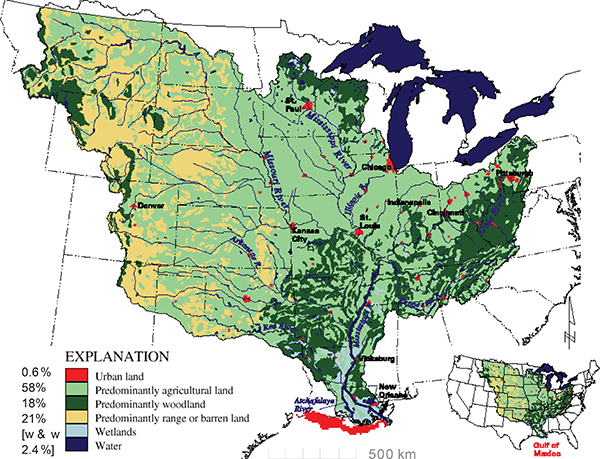

Nutrients originate from thousands of individual nonpoint and point sources in watersheds across the 31-state Mississippi River basin (MRB) (Figure 1-1). The size of the river basin, the wide dispersal and the many different sources of nutrients, and the considerable lag time between possible changes in nutrient yields across the basin and measured responses in the Gulf, all contribute to the complexity and challenge of addressing this national water quality problem.

This report was authored by the National Research Council (NRC) Committee on Clean Water Act Implementation Across the Mississippi River Basin and was sponsored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The charge to the committee was to advise EPA and other parties on strategic priorities and alternatives for specific actions regarding Clean Water Act implementation across the Mississippi River basin (see Box 1-1 for the committee’s full statement of task). This ad hoc committee was appointed in Summer 2009 and was overseen by the NRC’s Water Science and Technology Board (WSTB). The committee convened three meetings in 2009-2010. Its first meeting was held in Moline, Illinois, in September 2009, its second meeting was held in Washington, D.C., in December 2009, and its third and final meeting was held in New Orleans in March 2010. All meetings included open, public sessions with invited guest speakers (Appendix A lists invited guest speakers at these meetings), as well as closed sessions during which the committee discussed its scope of work and draft report.

This is the third report from the National Research Council that addresses issues regarding the Clean Water Act and MRB-NGOM water quality. The previous two reports were issued in 2008 and 2009. The 2008 report, sponsored by the McKnight Foundation, focused on Mississippi River water quality problems, data needs and system monitoring, water quality indicators and standards, and policies and implementation. The 2009 report, sponsored by EPA, focused on initiating pollutant control programs, identifying alternatives for allocating nutrient load reductions across the basin, and documenting the effectiveness of nutrient control strategies.

The 2008 and 2009 reports collectively contain an extensive set of findings and recommendations, many of which were directed to the EPA and its responsibilities under the Clean Water Act. Those two reports define an extensive, detailed, and action-oriented blueprint for initiating pollutant control programs, for promoting more systematic research on nutrient

FIGURE 1-1 Mississippi River basin, major tributaries, land uses, and typical summertime extent of northern Gulf of Mexico hypoxia (in red). The Mississippi River basin extends over 31 U.S. states and covers 41 percent of the conterminous U.S.

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from Goolsby (2000). © by the American Geophysical Union.

BOX 1-1

Committee on Clean Water Act Implementation Across the Mississippi River Basin

Statement of Task

This committee will provide advice to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and other relevant parties, on strategic priorities and alternatives for specific actions regarding Clean Water Act implementation across the Mississippi River basin. These other parties will include other federal agencies, state governments, U.S. congressional staff, municipalities, farmers and agricultural organizations, environmental groups, and the private sector.

The committee will convene a series of workshops that will feature expert guest speakers and dialogue with the committee regarding water quality and nutrient control activities and alternatives across the Mississippi River basin. In this process, the committee will identify pros, cons, and prospects of strategic priorities and alternative actions under the Clean Water Act to help achieve both water quality improvements across the river basin and into the northern Gulf of Mexico. The committee also will provide advice to enhance research and knowledge regarding various nutrient control actions and outcomes.

This activity will be a multi-year project and will produce a series of reports. This committee's first report will be issued near the end of its first year of existence. That report will identify key areas for EPA priority actions and advice on their implementation. All reports from this committee will be prepared, processed, and disseminated in accordance with standard National Academies procedures.

management alternatives and their water quality implications, and for establishing stronger federal inter-agency and inter-state coordination and leadership in addressing Mississippi River basin water quality issues (Box 1-2 lists key findings and recommendations from those reports). All recommendations made in those reports are within the context of the existing CWA and other existing legislation.

This report offers a small number of findings and recommendations, some of which are new and others of which build upon and reemphasize key findings and recommendations from the 2008 and 2009 reports. This is the first of two reports from this committee. The second and final report is planned for release in 2011.

Concerns about expansion of the hypoxic zone led to the establishment of the federalstate interagency Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force in 1997. In 1998, Congress passed the Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research and Control Act of 1998 (HABHRCA, Title VI of P.L. 105-383), gave statutory authority to the task force, and directed it to conduct a scientific assessment of the problem and develop an action plan to control it. The Task Force published an Action Plan in 2001 that drew heavily from an integrated assessment of hypoxia coordinated by the National Science and Technology Council and its

BOX 1-2

NRC 2008 AND 2009 REPORTS ON MISSISSIPPI RIVER BASIN AND NORTHERN GULF OF MEXICO WATER QUALITY AND THE CLEAN WATER ACT

Mississippi River Water Quality and the Clean Water Act: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. 2008.

This report addressed issues of Mississippi River water quality problems, data needs and system monitoring, water quality indicators and standards, and policies and implementation. Key findings and recommendations included:

- At the scale of the entire Mississippi River, nutrients and sediment are the two primary water quality problems.

- The lack of a centralized Mississippi River water quality information system and data gathering program hinders effective implementation of the Clean Water Act and acts as a barrier to maintaining and improving water quality along the Mississippi River and into the northern Gulf of Mexico

- The EPA has failed to use its mandatory and discretionary authorities under the Clean Water Act to provide adequate interstate coordination and oversight of state water quality activities along the Mississippi River that could help promote and ensure progress toward the act’s fishable and swimmable and related goals.

- It is imperative that USDA conservation programs be aggressively targeted to help achieve water quality improvements in the Mississippi River and its tributaries.

- EPA should develop water quality criteria for nutrients in the Mississippi River and the northern Gulf of Mexico.

Nutrient Control Actions for Improving Water Quality in the Mississippi River Basin and the Northern Gulf of Mexico. 2009.

This report addressed issues of initiating pollutant control efforts, allocation of load reductions, and documenting the effectiveness of pollutant loading reduction strategies.

-

The EPA and the USDA should jointly establish a Nutrient Control Implementation Initiative (NCII). Goals of the NCII should include:

demonstrate the ability to achieve reduced nutrient loadings by implementing and testing a network of demonstration projects;

evaluate local water and other benefits of nutrient control actions;

build an institutional model for cooperative research;

evaluate cost effectiveness, and economic and social viability, of nutrient control actions.

- Principles that should be followed in allocating cap load reductions include: select an interim goal for load reduction in an adaptive, incremental process; target watersheds to which load reductions are to be allocated; adopt a load reduction allocation formula that balances equity and cost-effectiveness, and; allow credit for past progress.

- The EPA and USDA should establish and jointly administer a Mississippi River Water Quality Center. Functions of the center should include: plan and administer the NCII projects; conduct cooperative basinwide water quality and land use monitoring; develop a land use/land cover database; identify additional watersheds for future inclusion in the NCII; and, produce reports on basinwide water quality assessment.

Committee on Environmental and Natural Resources (CENR, 2000). The Action Plan established a goal to reduce the zone to less than 5,000 square kilometers by 2015 through cost-effective voluntary actions by all sources and responsible governments (USEPA, 2001). Achievement of the 5,000 square kilometer goal was conditioned on funding of financial incentives for those voluntary actions. The Action Plan was updated in 2008 (USEPA, 2008).

Scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) have estimated the amounts of nutrients delivered to the Gulf from various sources (Alexander et al, 2008). According to those estimates, crop lands and pasture/rangelands contribute about 70 percent of the nitrogen load and about 80 percent of the phosphorus load to the NGOM. About 9 percent of nitrogen and 10-11 percent of phosphorus are attributable to urban and population-related activities.

In 2006, EPA’s Science Advisory Board (SAB) was asked to evaluate the most recent science on the hypoxic zone, as well as potential options for reducing the size of the zone. In its report, the SAB recommended a dual nutrient strategy of at least a 45 percent reduction in riverine total nitrogen flux and at least a 45 percent reduction in riverine total phosphorus flux relative to a 1980-1996 baseline (USEPA, 2007).

The 2008 report from the NRC commented on the Clean Water Act and its prospects for helping achieve national water quality goals and noted that, “…the Clean Water Act provides a legal framework that, if comprehensively implemented and rigorously enforced, can effectively address many aspects of intrastate and interstate pollution…” (NRC, 2008). That report, however, did not specifically consider or investigate prospects for achieving the more specific 45 percent reduction goals presented in the 2007 SAB report under existing Clean Water Act authorities. Although progress clearly can be made under existing authorities, it is far from clear that these 45 percent reductions could be achieved under authorities within the existing Clean Water Act. Limitations and ambiguities within the current CWA, which are discussed in more detail in the 2008 report, include the exemption of agricultural operations from permit requirements, delegation of nonpoint source regulation to the states, and language that limits direct application of Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDL) through the act’s permitting provisions only to point sources.

The remainder of this report is divided into four sections: (1) USDA’s Mississippi River Basin Healthy Watersheds Initiative, (2) numeric water quality criteria for the northern Gulf of Mexico, (3) a basinwide strategy for nutrient management and water quality; and (4) stronger leadership and collaboration.

USDA’S MISSISSIPPI RIVER BASIN HEALTHY WATERSHEDS INITIATIVE

The 2009 report from the NRC on nutrient control actions for water quality improvements recommended that: “The EPA and the USDA should jointly establish a Mississippi River basin Nutrient Control Implementation Initiative” (NRC, 2009). The report went on to explain that the goals of this NCII should include an ability to demonstrate reduced nutrient loadings by implementing and testing a network of nutrient control pilot projects, to evaluate local water quality benefits of nutrient control actions, and to build an institutional model for cooperative research among federal, state, and local organizations. The report

recommended that to initiate the NCII, “approximately 40 projects is a reasonable starting point” (ibid).

Soon after the 2009 report was issued, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced a new, four-year Mississippi River Basin Healthy Watersheds Initiative (MRBI). The program is designed to “voluntarily implement conservation practices that avoid, control, and trap nutrient runoff; improve wildlife habitat; and maintain agricultural productivity” (USDA, 2010). The MRBI is being implemented in 41 watersheds across 12 participating Mississippi River basin states—the ten states along the Mississippi River corridor, Indiana, and Ohio.

USDA and its NRCS deserve recognition in taking this decisive step toward more systematic nutrient management across the Mississippi River basin. Several elements of the MRBI parallel recommendations for the NCII. The MRBI is a step toward better water quality across the basin and into the northern Gulf. Ideally, the MRBI experience will serve to inform, support, and seed future initiatives for water quality improvements across the MRB and into the NGOM. Two broad areas will be especially important in helping the MRBI realize its considerable potential: (1) water quality and program evaluation, and (2) broadening the program to include collaboration with relevant entities from other governmental agencies, the private sector, and nongovernmental groups.

Key challenges for the MRBI include developing and implementing a systematic water quality monitoring system, and identifying goals or metrics to assess overall success for the program. The four-year time frame of the MRBI is not likely to produce statistically significant results of the relations between nutrient control/best management actions and impacts on water quality, but water quality improvements may be realized locally. Given the long time lag between nutrient control actions across the river basin and local and downstream responses in waters in the northern Gulf (likely to be at least ten years; NRC, 2009), it would be reasonable to initially focus on local water quality goals. MRBI performance goals ideally would reflect field-level achievements and programmatic successes. Development and evaluation of program goals will be important in learning from, and building upon, strengths and weaknesses of the MRBI.

Results from water quality monitoring will be essential to addressing MRB-NGOM water quality management and as part of an adaptive approach that evaluates outcomes of management actions and uses results to adjust and improve upon future strategies. An adaptive environmental assessment and management promotes an iterative approach in which experience is evaluated, and adjusted to, to help counter the inherent uncertainties of large-scale environmental systems. Monitoring, and the feedback derived from it, therefore provides a basis for learning and understanding in an unpredictable setting. The process of adjusting management actions based on new understanding is a staple of adaptive management (e.g., see NRC, 2004) and will be necessary for addressing a problem with the complexity of MRB-NGOM water quality. This provides the rationale for purposeful monitoring at multiple scales, over a long period of time, to then be integrated into an adaptive management approach.

To be effective, any long-term strategy for Mississippi River basin water quality will reflect collaboration among MRB states and federal agencies with major water management responsibilities in the basin and the northern Gulf. Given its Clean Water Act authorities and responsibilities, close collaboration with EPA will be essential in areas of, for example, water quality monitoring, statistical approaches for evaluating effects of nutrient control actions,

development of Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) plans, advice regarding numeric nutrient criteria development, and interstate coordination.

The importance and value of USDA and EPA collaboration on these issues is explained in detail in NRC, 2009. EPA could especially lend support to the MRBI in areas related to monitoring, research, and evaluation—all examples of agricultural and environmental intelligence that can inform and improve future water quality management strategies and actions. Other federal agencies—including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)—play important roles in MRB and NGOM water quality monitoring and management. As an example, scientists from the USGS Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center in LaCrosse, Wisconsin have collected data and conducted investigations of Mississippi River water quality and ecology since the 1980s. At a larger scale, the USGS also operates the National Stream Quality Accounting Network (NASQAN). Although the extent of the NASQAN program has diminished from its peak in the 1970s, it could be a useful complement to any water quality monitoring activities in the Mississippi River basin. Finally, the USGS has provided specific advice regarding a water quality monitoring strategy for the MRB and NGOM. In a 2004 report developed under the auspices of the Task Force, a Monitoring, Modeling, and Research (MMR) strategy was developed that describes a framework for modeling, modeling and research activities (USGS, 2004). The report recommended a four-level monitoring strategy, including measurement of fluxes near the mouths of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers, outflows of the nine major subbasins, outflows of selected priority watersheds at the scale of USGS six-digit hydrologic units and, at a smaller scale, estimates of effects of management practices. Recommendations from the USGS 2004 report could be implemented usefully within the context of the MRBI (or as part of the NCII recommended in the 2009 NRC report).

The USGS and other federal agencies will play important, long term roles in achieving improvements in MRB and NGOM water quality monitoring and quality. Nevertheless, given EPA’s Clean Water responsibilities, stronger USDA-EPA collaboration will be essential to future and sustained MRB and NGOM water quality improvements (see also NRC, 2008 and 2009).

The EPA should explore ways in which the agency can support activities related to MRBI evaluation. Ways in which EPA might assist include:

- identifying measures of progress;

- gauging the cost effectiveness of various nutrient control actions;

- assisting with MRBI project evaluation, and;

- establishing water quality monitoring projects and indicators of progress.

NUMERIC WATER QUALITY CRITERIA FOR THE NORTHERN GULF OF MEXICO

The 2008 NRC report recommended that “the EPA should develop water quality criteria for nutrients in the Mississippi River and the northern Gulf of Mexico” (NRC, 2008). That report explained that even if all of the ten states along the Mississippi River developed and fully implemented state-level water quality criteria, their cumulative efforts would not necessarily begin to reduce the areal extent of the NGOM hypoxic zone. Further, the report explained that

“[a]n adequate approach to remediating northern Gulf of Mexico hypoxia would entail establishing numeric nutrient criteria for the mouth of the Mississippi and Gulf of Mexico waters that permit no more nutrient flow into the Gulf than could be accommodated by natural processes without significant oxygen depletion” (NRC, 2008, p. 126).

Establishing numeric criteria for nutrients in the federal territorial waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico would establish an overall goal of MRB nutrient water pollution management.1 This action would have only one immediate legal consequence under the Clean Water Act: Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas would have to determine whether their state Gulf waters meet the new criteria. From there, assuming that the state waters of the Gulf of Mexico did NOT meet the new criteria, each state would have to list its coastal waters as “impaired” in the next state Section 303(d) list and begin the Section 303 Total Maximum Daily Load prioritization process, which is designed to identify sources of pollutants across a watershed and create a plan for reducing pollutant loadings.2 Section 303(d) of the Clean Water act requires each state to identify “impaired waters” of the state. This impairment determination is based on a comparison of observed conditions to state-promulgated water quality standards. Existence of numeric criteria makes this process of determining whether a waterbody is impaired more straightforward and transparent. Subsequent to this listing, each state also is required to prioritize its impaired waters and develop a Total Maximum Daily Load determination, which includes a determination of the maximum allowable loading of the problematic pollutant or pollutants. The resulting TMDL plan must be allocated to point sources and nonpoint sources, and include a margin of safety. If states do not meet these requirements, EPA is required to do so. Hence, establishing specific numeric criteria for Gulf coastal waters will set into motion requirements to develop plans for pollutant load reductions to meet those standards (see NRC, 2008 for details regarding implications of interstate water quality standards and TMDLs).

If the new numeric nutrient criteria apply to the federal waters of the Gulf of Mexico, the process for the EPA is less clearly specified in the Clean Water Act in Section 303, which by its language, applies only to states. Nevertheless, the Act itself clearly applies to the federal zones of the ocean, and the EPA has frequently issued National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES, as specified within Clean Water Act Section 402; see NRC, 2008) permits for discharges of pollutants into federal ocean waters. Any apparent ambiguities regarding the application of the TMDL process to the NGOM are superseded by the authority clearly vested with EPA elsewhere in the Clean Water Act to protect water quality in the federal zones of the ocean. Along with comprehensive authority given to EPA over oceans and interstate pollution, the Clean Water Act allows for the crafting of a flexible and long-term implementation plan for achieving MRB water quality improvements throughout the Mississippi River basin, with a goal

_________________

1An alternative to establishing criteria for nutrients as a water quality goal would be to establish a dissolved oxygen goal. Criteria for dissolved oxygen have been established and used as a goal for reducing hypoxia in the Chesapeake Bay, but the primary strategy to achieve that goal has been reduction in nutrient loads. In the Mississippi River basin and northern Gulf, nutrient loads from nonpoint sources are the prevailing driver of Gulf of Mexico hypoxia. Nutrient criteria thus represent a more direct means of addressing nutrient loadings across the basin and into the Gulf.

2Section 303 of the Clean Water Act addresses water quality standards and the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) process. For more detail on Section 303 and its programs, see NRC, 2008, esp. pp. 78-85.

to eventually reduce minimize NGOM hypoxia (See NRC, 2009 for discussion of CWA Sections 102, 104, and other relevant authorities.).

Importantly, and as already noted, numeric nutrient criteria for the northern Gulf of Mexico would represent a goal for the entire Mississippi River basin. Establishing numeric criteria for the northern Gulf would act as a driver and allow EPA and the Mississippi River states to begin working upstream in this large, complex watershed, as numeric criteria would provide an end point that could serve as the basis for setting standards in upstream states of the basin. Moreover, implementing numeric nutrient criteria in the federal waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico could provide the EPA with leverage when encouraging or mandating establishment of state numeric standards. Establishing NGOM numeric nutrient criteria also would complement the MRBI in moving toward a more systematic, adaptive, and coordinated basin-wide approach to managing nutrients and water quality.

To reaffirm and reemphasize a recommendation from the 2008 NRC report, the EPA should establish numeric criteria for nutrients for the waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico.

A BASINWIDE STRATEGY FOR NUTRIENT MANAGEMENT AND WATER QUALITY

Given the many challenges and complexities regarding water quality issues in the Mississippi River basin and the northern Gulf of Mexico, a comprehensive, basinwide strategy for improvement of conditions in freshwater and coastal systems would be of great value. The Mississippi River is a resource of tremendous economic and environmental importance to the nation, and its fluxes of water, nutrients, and sediment into the NGOM are essential to coastal water quality, coastal restoration plans, living and nonliving resources, and mitigation of unexpected environmental disasters like the oil spill in late spring and summer, 2010. These many water quality concerns add urgency to the importance of reducing nutrient loadings and improving water quality across the MRB and into the NGOM. Progress to date toward a comprehensive water quality management program for the basin remains limited.

The following section describes some previous efforts toward Mississippi River basinwide water quality improvements, efforts in the Chesapeake Bay toward comprehensive water quality management and assessment, and a 2007 report from the EPA Science Advisory Board that is relevant to these topics. It concludes with a recommendation for a more action-oriented, basinwide strategy for Mississippi River and northern Gulf of Mexico water quality management.

The Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force

An initial plan to reduce hypoxia in the northern Gulf of Mexico was prepared by the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force in 2001 (USEPA, 2001). Task Force members include EPA; USDA and its Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and its Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS); the Department of the Interior and its National Park

Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.S. Geological Survey; the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and its Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC); and the ten states along the Mississippi River corridor.

A revised version of this “Action Plan” was published in 2008 and entitled Gulf Hypoxia Action Plan 2008 for Reducing, Mitigating, and Controlling Hypoxia in the Northern Gulf of Mexico and Improving Water Quality in the Mississippi River Basin (USEPA, 2008). This report notes progress since 2001, lays out a set of general goals, and sets forth principles for guiding development of more detailed plans.

A weakness of the 2008 Action Plan is that it contains nothing to suggest that actions discussed in the plan (and a related FY2008 Operating Plan) will in fact achieve the goals. It remains an open question whether the goals can be achieved even if the proposed actions are implemented. The voluntary programs presented within the Action Plan, which rely solely on existing authorities, may not be viable or ensure progress toward water improvements. Also, relying solely on existing incentives and authorities could lead to misallocation of financial resources needed to realize substantial progress.

The Task Force adopted a decentralized approach to formulating management plans, relying largely on states to develop statewide nutrient reduction programs in the absence of quantitative targets. Over the course of its history, the Task Force has issued several documents and reports, including Action Plans in 2001 and 2008. These plans have value in identifying alternatives for helping control nutrient yields and in promoting dialogue on MRB-NGOM water quality challenges. They have not, however, committed any agency or entity to take any specific action, nor have they acknowledged that key agencies in addressing water quality impairments across the Mississippi River basin may not have sufficient resources or commitment to help address these problems. Thus, although recommendations from the Task Force and Action Plans have been reasonable, they do not constitute a comprehensive basinwide program that provides reasonable assurance for implementing specific actions and for realizing progress toward water quality goals.

Collaborative Water Quality Assessment and Management for the Chesapeake Bay

There are many programs in the Mississippi River basin, and elsewhere, that can be used as a foundation for a basinwide nutrient and water quality management strategy. For example, a more action-oriented strategy could build on experiences gained in the process of developing and implementing water quality evaluation and nutrient control initiatives for the Chesapeake Bay, where initiatives to improve water quality have been ongoing for over 25 years with substantial federal and state collaboration. The Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) was established in 1983 by formal agreement and with the signatures of the governors of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia; the mayor of the District of Columbia; and the EPA administrator. Subsequent agreements among these participants, along with Delaware, New York, and West Virginia, have aimed to promote cooperation and achieve nutrient and sediment reduction targets. The Chesapeake 2000 (2K) initiative contains a commitment by Chesapeake Bay watershed jurisdictions to determine nutrient and sediment load reductions necessary to achieve water

quality conditions to protect aquatic resources. In 2003, the six watershed states, the District of Columbia, and EPA agreed on required load reductions that were allocated to each of the watershed’s nine major tributary basins and jurisdictions in the form of cap loads. More recently, in May 2009, President Obama signed Executive Order 13508, for Chesapeake Bay Protection and Restoration (Exec. Order 13508, 2009).

The Chesapeake Bay is the site of an extensive program for water quality monitoring, modeling, and evaluation. The Chesapeake Bay Program uses three main models—an estuary model, an airshed model, and a watershed model—to simulate changes in the Bay ecosystem resulting from population increases, changing land uses and cover, or changes in pollution management actions. States in the bay watershed also have been developing and implementing a variety of nutrient trading policies, and the EPA is exploring an interstate water quality trading regime for a portion of the Chesapeake watershed (further details of efforts in the Chesapeake Bay can be found at: http://www.chesapeakebay.net/).

The Chesapeake Bay and the Mississippi River basin clearly exhibit many differences. Nevertheless, the extensive experience in the Chesapeake with interstate collaboration, and efforts there to allocate nutrient load reductions and evaluate water quality, provide Mississippi River basin states and federal agencies many possible lessons that could be drawn upon in developing similar agreements and programs. As was noted in the NRC, 2008 report:

The Mississippi River basin states and the federal government should look to the Chesapeake Bay Program as a useful model in guiding future Mississippi River federal-interstate collaboration on defining and addressing water quality problems, setting science-based water quality standards, and establishing a comprehensive water quality monitoring program (NRC, 2008).

The 2007 Report from EPA’s Science Advisory Board

A 2007 report from EPA’s Science Advisory Board (SAB) carefully evaluated recent advances in science related to hypoxia and potential options for reducing the areal extent of the hypoxic zone and improving water quality in the basin (USEPA, 2007). A 2008 updated report from the SAB provides insights into the costs and broader economic welfare implications of implementing management strategies (USEPA, 2008). After reviewing a number of basinwide integrated economic-biophysical models published over the period 1999-2007, the SAB noted that the large-scale policy models have both strengths and weaknesses. Some of the models cover only a limited range of management options and policy instruments. The SAB recommended that models be enhanced to include land uses and a broad range of options at finer scales than are represented in existing modes. Despite those limitations, the SAB concluded that available evidence:

suggests that it is probable that social welfare in the basin can be maintained while achieving the goal of a 5-year running average of 5000 km2 for the hypoxic zone.

Most importantly, welfare losses from costs incurred to control hypoxia in the Basin will

be offset, at least in part, by co-benefits of nutrient reductions (USEPA, 2007).

Toward a More Action-Oriented Plan for Water Quality Improvements

This section draws from and builds upon many recommendations from the 2008 and 2009 NRC reports (for example, the 2009 report recommended establishment of a Nutrient Control Implementation Initiative; Box 1-2 and NRC, 2009). It is presented to encourage EPA, USDA, and the Mississippi River basin states to move more decisively toward a comprehensive program for nutrient control, water quality monitoring, and institutional collaboration.

Basic elements of a more action-oriented strategy for the Mississippi River basin could include:

- establishment of a series of interim water quality goals to be achieved over specified time horizons, and that could ultimately lead to satisfying numeric nutrient criteria for the Gulf and tributary states;

- identification of programs and management measures to be implemented;

- allocation of loading goals to tributary watersheds;

- setting of milestones for programs and management measures to be achieved over relevant time horizons;

- development of measurable indicators of progress toward achievement of goals; and

- establishment of processes for data collection, analysis, distribution, and public reporting;

- agreement by state and federal officials on accountability, outcomes assessment, and penalties for not meeting milestones and deadlines; and,

- comprehensive assessment of overall goals for implementing necessary measures.

Although efforts in the Mississippi River basin and northern Gulf of Mexico are less mature than those for the Chesapeake Bay, many pieces necessary to formulate a stronger basinwide strategy are in place. The 2008 Action Plan provides valuable information about past initiatives and current trends. USDA’s MRBI is a vital step toward identifying cost-effective agricultural measures and their performance at watershed scales. Ongoing water quality modeling efforts by USGS scientists, namely the development of a Spatially Referenced Regressions on Watershed Attributes, or “SPARROW” model, track long-term fluxes of nutrients and can be used as a basis for making at least tentative load allocations (Alexander et al., 2008).

Development of a basinwide strategy as outlined above would complement both the establishment of NGOM numeric nutrient criteria and the use of the MRBI to move toward a more systematic, adaptive, and coordinated basin-wide approach to managing nutrients and water quality.

The EPA, its partner federal agencies, and the Mississippi River basin states—especially the states along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers—should develop a more action-oriented basinwide strategy to address nutrient-related water quality problems throughout the Mississippi River basin and northern Gulf of Mexico.

STRONGER LEADERSHIP AND COLLABORATION

Recommendations from the 2008 and 2009 NRC reports that relate to stronger leadership and collaboration include:

- “There is a clear need for federal leadership in system-wide monitoring of the Mississippi River. The EPA should take the lead in establishing a water quality data sharing system for the length of the Mississippi River…. The EPA should draw upon the considerable expertise and data held by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the USGS, and NOAA” (NRC, 2008).

- “The EPA should act aggressively to ensure improved cooperation regarding water quality standards, nonpoint source management and control, and related programs under the Clean Water Act” (NRC, 2008).

- “The EPA and the USDA should jointly establish a Nutrient Control Implementation Initiative (NCII)” (NRC, 2009).

- “[A] Mississippi River Water Quality Center should be established. The EPA and the USDA should administer the center…. Participation of other bodies that play important roles in water quality monitoring—such as the USGS, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and state natural resources and water quality agencies—will be vital to the center’s operations and functions” (NRC, 2009).

Realizing progress toward reducing the NGOM hypoxic zone and improving MRB water quality will require a sustained, multi-decade commitment from organizations at multiple levels. It also will require considerable resources and patience, an important lesson from the long-term efforts in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. The provisions of the Clean Water Act make clear that the EPA is the federal agency with responsibility for coordinating state efforts for protection and maintenance of water quality in interstate waters. Because of this responsibility and its unique role as a regulator, the EPA is also best positioned to coordinate inter-agency efforts on water quality in the Mississippi River. This observation is confirmed by the experience with the longterm efforts in the Chesapeake Bay. States along the Mississippi River and across the basin support many important and valuable water quality monitoring programs, many of which have a strong focus on nutrients. Even though some of these states may have programs designed to better understand and address the nutrient problem, from a basin wide perspective, there is currently no coordinated effort among states for managing nutrient loadings to the Mississippi River.

The NGOM hypoxia problem will not be easily or quickly addressed. Positive, local results across the river basin will require decades of dedicated effort, and clear evidence of downstream water quality effects or improvements in the NGOM likely will require at least ten years to detect (NRC, 2009). At the same time, scientific evidence of linkages between nutrient loadings across the watershed and NGOM hypoxia is strong, and there also exist shorter-term opportunities for improvements in local water quality conditions. If decisive pollutant control actions are delayed, it will take longer until positive results are seen. If the nutrient management and related water quality challenges across the MRB and into the NGOM are to be decisively and systematically addressed, more aggressive efforts than those taken to date will be required.

The challenge of addressing NGOM hypoxia goes beyond the mandate and resources of any individual government agency. The current framework of mainly voluntary coordination of actions and programs, although useful for promoting dialogue and raising awareness of water quality issues, has not realized substantive accomplishments in terms of on-the-ground implementation or documented improvements in water quality. Lasting solutions to Mississippi River basin and northern Gulf of Mexico water quality problems will require stronger inter-agency collaboration and sustained support from the Administration and the U.S. Congress than have been exhibited to date.

Several recommendations from the 2008 and 2009 NRC reports provide opportunities to establish stronger inter-agency cooperation and federal leadership. Those recommendations include, for example, creating a water quality data sharing system for the length of the Mississippi River (NRC, 2008) and establishing a Mississippi River Water Quality Center (NRC, 2009). All these examples offer opportunities for EPA, USDA, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the USGS, and NOAA to work collaboratively on a variety of scientific, administrative, technical, and institutional issues. The 2008 NRC report noted the importance of interstate cooperation, recommending that the lower Mississippi River corridor states (Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee) create an entity similar to the Upper Mississippi River Basin Association (UMRBA; NRC, 2008). The experiences in water quality assessment and management in the Chesapeake Bay also may provide insights about implementing and carrying out relevant interagency arrangements and interstate agreements. Interstate compacts and river basin commissions have proven useful in addressing water quality issues in some U.S. river systems, such as the Ohio and the Susquehanna Rivers. The 2008 NRC report listed principles for interstate cooperation for water quality management, while noting the challenges involved in developing and establishing these types of programs (NRC, 2008). That 2008 report also discussed interstate arrangements other than compacts for addressing water quality challenges, such as the UMRBA.

None of these initiatives would be easily implemented, inexpensive, or promise immediate results. All of them, however, are examples of the type of stronger inter-agency collaboration that will be necessary to more effectively address water quality problems across the basin and into the NGOM.

The EPA, its partner federal agencies, the Congress, the Administration, and the Mississippi River basin states should provide a stronger, more coordinated commitment in order to develop long-term, adaptive, collaborative actions for effectively addressing water quality problems across the MRB and into the NGOM.