Certifiable Autonomous Flight Management for Unmanned Aircraft Systems

ELLA M. ATKINS

University of Michigan

The next-generation air transportation system (NextGen) will achieve unprecedented levels of throughput1 and safety by judiciously integrating human supervisors with automation aids. NextGen designers have focused their attention mostly on commercial transport operations, and few standards have been proposed for the burgeoning number of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS).2 In this article, I describe challenges associated with the safe, efficient integration of UAS into the National Airspace System (NAS).

CURRENT AIRCRAFT AUTOMATION

Although existing aircraft autopilots can fly from takeoff through landing, perhaps the most serious technological impediment to fully autonomous flight is proving their safety in the presence of anomalies such as unexpected traffic, onboard failures, and conflicting data. Current aircraft automation is “rigid” in that designers have favored simplicity over adaptability. As a result, responding in emergency situations, particularly following events that degrade flight performance (e.g., a jammed control surface, loss of engine thrust, icing, or damage to the aircraft structure) requires the intervention and ingenuity of a human pilot or operator.

If the automation system on a manned aircraft proves to be insufficient, the onboard flight crew is immersed in an environment that facilitates decision making and control. Furthermore, modern aircraft rarely experience emergencies because their safety-critical systems are designed with triple redundancy.

ENSURING SAFETY IN UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEMS

To be considered “safe,” UAS operations must maintain acceptable levels of risk to other aircraft and to people and property. An unmanned aircraft may actually fly “safely” throughout an accident sequence as long as it poses no risk to people or property on the ground or in the air. Small UAS are often considered expendable in that they do not carry passengers and the equipment itself may have little value. Thus, if a small UAS crashes into unimproved terrain, it poses a negligible risk to people or property.

UAS cannot accomplish the ambitious missions for which they are designed, however, if we limit them to operating over unpopulated regions. To reap the benefits of UAS, we must develop and deploy technologies that decrease the likelihood of a UAS encountering conditions that can lead to an incident or accident.

However, the recipe for safety on manned aircraft is impractical for small UAS. First, triple redundancy for all safety-critical systems would impose unacceptable cost, weight, and volume constraints for small aircraft. Second, although transport aircraft typically fly direct routes to deliver their payloads, surveillance aircraft are capable of dynamically re-planning their flight trajectories in response to the evolving mission or to observed data (e.g., the detection of a target to be tracked).

Finally, UAS are operated remotely, and operators are never directly engaged in a situation in which their lives are at risk. In fact, operators can only interact with a UAS via datalink, and “lost link” is currently one of the most common problems.3

SAFETY CHALLENGES FOR SMALL UNMANNED AIRCRAFT

With limited redundancy, highly dynamic routes, and strictly remote supervision, small UAS face formidable automation challenges. As the number of unmanned aircraft increases and as safety-oriented technology development continues to lag behind the development of new platforms, mission capabilities, and operational effi-ciency (e.g., one operator for multiple vehicles), it is becoming increasingly urgent that these issues be addressed. In addition, a large user base

|

3 |

This issue was recently brought to our attention when a Fire Scout UAS aircraft lost its communication link and inappropriately flew quite close to restricted airspace around Washington, DC. (http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/26/us/26drone.html?_r=4&partner=rss&emc=rss). |

for UAS is emerging, which includes military and homeland security missions and commercial ventures.

Making the routine operation of unmanned aircraft safe wherever they are needed will substantially reduce the need for costlier manned flights that have a much greater adverse impact on the environment. However, for unmanned aircraft to operate near other aircraft or over populated areas, they must be capable of managing system failures, lost links, and dynamic routing, including collision avoidance, in a way that is “safe” for people and property.

We are currently working to augment autonomous decision making in the presence of actuator or sensor failures by expanding the definition of “flight envelope” to account for evolving physical, computational, perceptual, and environmental constraints. The flight envelope is traditionally defined by physical constraints, but under damage or failure conditions the envelope can contract. An autonomous flight controller must be capable of identifying and respecting these constraints to minimize the risk of loss-of-control as the aircraft continues on its mission or executes a safe emergency landing.

The autonomous flight manager can minimize risk by following flight plans that maximize safety margins first and then maximize traditional efficiency metrics (e.g., energy or fuel use). Thus flight plans for UAS may first divert the aircraft away from populated regions on the ground or densely occupied airspace and then decide whether to continue a degraded flight plan or end the mission through intentional flight termination or a controlled landing in a nearby safe (unpopulated) area. The key to certification of this autonomous decision making will be guaranteeing that acceptable risk levels, both real and perceived, are maintained.

ADDRESSING SAFETY CHALLENGES

In the discussion that follows, we look first at the problem of certifiable autonomous UAS flights in the context of current flight and air traffic management (ATM) technologies, which are primarily designed to ensure safe air transportation with an onboard flight crew. In this context, we also describe current and anticipated roles for automation and human operators.

Next, we characterize emerging UAS missions that are driving the need for fully autonomous flight management and integration into the NAS. Because loss-of-control is a major concern, I suggest an expanded definition of the flight envelope in the context of a real-life case study, the dual bird strike incident of US Airways Flight 1549 in 2009. That incident highlighted the need for enhanced automation in emergency situations for both manned and unmanned aircraft.

Finally, challenges to certification are summarized and strategies are suggested that will ultimately enable UAS to fly, autonomously, in integrated airspace over populated as well as rural areas.

FLIGHT AND AIR TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT: A SYSTEM-OF-SYSTEMS

In the NextGen NAS, avionics systems onboard aircraft will be comprised of a complex network of processing, sensing, actuation, and communication elements (Atkins, 2010a). UAS, whether autonomous or not, must be certified to fit into this system. All NextGen aircraft will be networked through datalinks to ATM centers responsible for coordinating routes and arrival/departure times.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and its collaborators have proposed a system-wide information management (SWIM) architecture (www.swim.gov) that will enable collaborative, flexible decision-making for all NAS users; it is assumed that all NextGen aircraft will be capable of accurately following planned 4-D trajectories (three-dimensional positions plus times), maintaining separation from other traffic, and sharing pertinent information such as GPS coordinates, traffic alerts, and wind conditions. Protocols for system-wide and aircraft-centric decision making must be established to handle adverse weather conditions, encounters with wake turbulence, and situations in which other aircraft deviate from their expected routes.

To operate efficiently in controlled NextGen airspace, all aircraft will be equipped with an onboard flight management system (FMS) that replicates current functionality, including precise following of the approved flight plan, system monitoring, communication, and pilot interfaces (Fishbein, 1995; Liden, 1994). Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast (ADS-B) systems will also communicate aircraft status information (e.g., position, velocity) to ensure collision avoidance. Without such equipment, it will be difficult to guarantee that traffic remains separated throughout flight, especially when manned and unmanned aircraft are involved.

Low-Cost Flight Management Systems

Small operators, from general and sports aviation to unmanned aircraft, will require low-cost options to the current FMS. Although advanced miniaturized electronics can make low-cost, lightweight FMS possible (Beard, 2010), producing and marketing these systems will require a concerted effort in the face of potentially slim profit margins and formidable validation and verification requirements.

The current FMS can devise and follow a flight plan from origin to destination airport. In the future, automation in both manned and unmanned aircraft is expected to include making and coordinating dynamic routing decisions based on real-time observations (e.g., weather), other traffic, or even mission goals (e.g., target tracking). Quite simply, we are rapidly moving toward collaborative human-machine decision making or fully autonomous decision making rather than relying on human supervisors of autonomous systems, particularly if operators are not onboard.

From Lost Link to Optional Link

Today’s unmanned aircraft are flown by remote pilots/operators who designate waypoints or a sequence of waypoints, as well as a rendezvous location. However, as was mentioned above, communication (lost link) failure is a common and challenging unresolved issue for UAS. Addressing this problem will require that developers not only improve the availability of links, but simultaneously pursue technological advances that will render links less critical to safety.

As the level of autonomy increases to support extended periods of operation without communication links, UAS must be able to operate “unattended” for extended periods of time, potentially weeks or months, and to collect and disseminate data without supervision unless the mission changes.

Sense-and-Avoid Capability

Because human pilots cannot easily see and avoid smaller UAS, “sense and avoid” has become a top priority for the safe integration of UAS into NAS. A certified sense-and-avoid technology will provide another step toward fully autonomous or unattended flight management.

EMERGING UNMANNED MISSIONS

A less-studied but critical safety issue for UAS operations as part of NAS is maintaining safe operations in the presence of anomalies. Researchers are beginning to study requirements for autonomously carrying out UAS missions (Weber and Euteneuer, 2010) with the goal of producing automation technology that can be certified safe in both nominal and conceivable off-nominal conditions. In this section, we focus on the “surveillance” missions that distinguish UAS—particularly small unmanned aircraft that must operate at low cost in sparsely populated airspace—from traditional transport operations.

Traditional Transport Operations

Traditional transport aircraft have a single goal—to fly a human or cargo payload safely from an origin to a destination airport with minimal cost to the airline. The “best” routes are, therefore, direct, with vectors around traffic or weather as needed. Schedules can be negotiated up to flight time, and passengers and cargo carriers expect on-time delivery, as costs increase with delay. In the context of autonomous transport UAS (e.g., cargo carriers), issues include loss of facilities or adverse weather at the destination airport, failure or damage conditions (e.g., loss of fuel or power) that render the destination unreachable, and security issues that result in a system-wide change in flight plans (e.g., temporary flight restrictions).

Unmanned Surveillance Aircraft

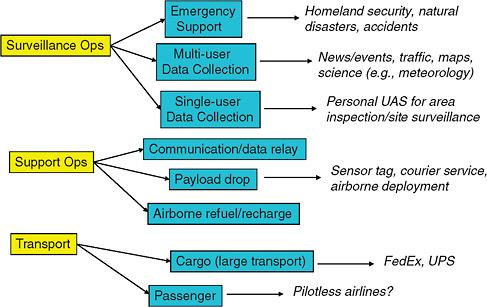

Unlike traditional transport aircraft, the goal of surveillance unmanned aircraft may be to search a geographical region, to loiter over one or more critical sites, or to follow a surveillance target along an unpredictable route. A summary of potential commercial applications (Figure 1) that complement the myriad of military uses for surveillance flights, shows that surveillance and support are the primary emerging mission categories that will require the expansion of existing NAS protocols to manage dynamic routing and the presence of UAS in (1) uncontrolled, low-altitude airspace currently occupied primarily by general aviation aircraft and (2) congested airport terminal areas where traffic is actively managed (Atkins et al., 2009).

This will mean that UAS will mix with the full fleet of manned operations, ranging from sports and recreational aircraft operated by pilots with limited training to jets carrying hundreds of passengers. UAS missions also will overfly populated areas for a variety of purposes, such as monitoring traffic, collecting atmospheric data over urban centers, and inspecting sites of interest. Even small unmanned aircraft have the capacity to provide support for communication, courier services, and so on.4

Unmanned aircraft can work in formations that can be modeled and directed as a single entity by air traffic controllers. This capability can give controllers much more leeway in sequencing and separating larger sets of traffic than would be possible if all UAS flights were considered distinct.

UAS teams may also negotiate tasks but fly independent routes, such as when persistent long-term coverage is critical to a successful mission or when cooperative coverage from multiple angles is necessary to ensure that a critical ground target is not lost in an urban environment. Some activities may be scheduled in advance and prioritized through equity considerations (e.g., traffic monitoring), but activities related to homeland security or disaster response are unscheduled and may take priority even over airline operations.

Although the effects of high-altitude UAS must be taken into account by NAS, low-altitude aircraft operating over populated regions or in proximity to major airports will be the most challenging to accommodate in the NextGen NAS. UAS must, of course, be safe, but they must also be fairly accommodated through the extension of NAS metrics (e.g., access, capacity, efficiency, and flexibility) so they can handle operations when persistent surveillance over a region of interest is more important than equitable access to a congested airport runway.

FIGURE 1 Emerging commercial applications for unmanned aircraft. Source: Atkins et al., 2009.

EXTENDING THE FLIGHT ENVELOPE TO MINIMIZE THE RISK OF LOSS-OF-CONTROL

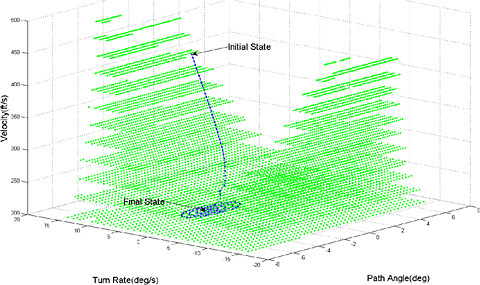

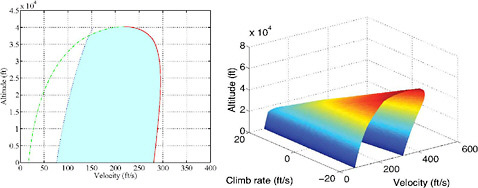

Loss-of-control, the most frequent cause of aviation accidents for all vehicle classes, occurs when an aircraft exits its nominal flight envelope making it impossible to follow its desired flight trajectory (Kwatny et al., 2009). Current autopilot systems rely on intuitive, linearized, steady-flight models (Figure 2) that reveal how aero-dynamic stalls and thrusts constrain the flight envelope (McClamroch, in press).

To ensure the safe operation of UAS and to prove that autonomous system performance is reliable, an FMS for autonomous aircraft capable of provably avoiding loss-of-control in all situations where avoidance is possible will be essential. This will require that the autonomous system understand its flight envelope sufficiently to ensure that its future path only traverses “stabilizable” flight states (i.e., states the autonomous controller can achieve or maintain without risking loss-of-control).

Researchers are beginning to develop nonlinear system-identification and feedback control algorithms that offer stable, controlled flight some distance beyond the nominal “steady flight” envelope (Tang et al., 2009). Such systems could make it feasible for an autonomous system to “discover” this more expansive envelope (Choi et al., 2010) and continue stable operation despite anomalies

FIGURE 2 Examples of steady-level (left) and 3-D (right) traditional flight envelopes. Source: McClamroch, in press.

in the environment (e.g., strong winds) or onboard systems (e.g., control-surface failures or structural damage) that would otherwise lead to loss-of-control.

Flight Envelope Discovery

Figure 3 shows the flight envelope for an F-16 with an aileron jammed at 10 degrees. In this case, the aircraft can only maintain steady straight flight at slow speeds. The traversing curve shows an example of a flight envelope discovery process incrementally planned as the envelope is estimated from an initial high-speed turning state through stabilizable states to a final slow-speed straight state (Yi and Atkins, 2010).

This slow-speed, gentle-descent final state and its surrounding neighborhood are appropriate for final approach to landing, indicating that the aircraft can safely fly its approach as long as it remains within the envelope. Once the envelope has been identified, a landing flight plan guaranteed to be feasible under the condition of the control surface jam can be automatically generated.

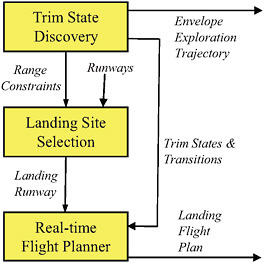

Figure 4 illustrates the emergency flight management sequence of discovering the degraded flight envelope, selecting a nearby landing site, and constructing a feasible flight plan to that site. Although a runway landing site is presumed in the figure, an off-runway site would probably be selected for a small UAS that required little open space for landing. The sequence in Figure 4 mirrors the emergency procedures a pilot would follow when faced with degraded performance. Note that all of the steps in this process could be implemented autonomously with existing technology.

Autonomous Reaction to Off-Nominal Conditions

The remaining challenge is to prove that such an autonomous system is capable of recognizing and reacting to a sufficient range of off-nominal situations to be considered “safe” without a human pilot as backup. To illustrate how autonomous emergency flight management could improve safety, we investigated the application of our emergency flight planning algorithms to the 2009 Hudson River landing (Figure 5) of US Airways Flight 1549 (Atkins, 2010b).

About two minutes after the aircraft departed from LaGuardia (LGA) Airport in New York, it encountered a flock of large Canada geese. Following multiple bird strikes, the aerodynamic performance of the aircraft was unchanged, but propulsive power was no longer available because of the ingestion of large birds into both jet engines, which forced the aircraft to glide to a landing. In this event, the pilot aptly glided the plan to a safe landing on the Hudson River. All passengers and crew survived, most with no injuries, and the flight crew has been rightly honored for its exemplary performance.

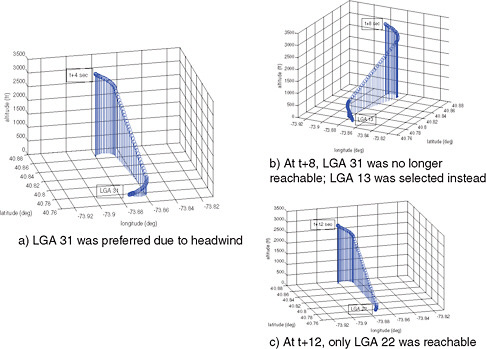

In the case of Flight 1549, our adaptive flight planner first identified the glide (no-thrust) footprint from the coordinates at which thrust was initially lost. This analysis indicated that the aircraft could return to LGA as long as the return was initiated rapidly, before too much altitude was lost. Our landing site search algorithm prioritized LGA runway 31 as the best choice because of its headwind, but runways 13 and 22 were also initially reachable.

Figure 6 illustrates the feasible landing trajectories for Flight 1549 automatically generated in less than one second by our pre-existing engine-out flight planner adapted to Airbus A320 glide and turn capabilities. Notably, runway 31 was reach-

FIGURE 5 Post-landing photo of US Airways Flight 1549 in the Hudson River (http://www.wired.com/images_blogs/autopia/2010/01/us_airways_1549_cropped.jpg).

FIGURE 6 Feasible trajectories for Flight 1549 to return to LaGuardia Airport. Source: Atkins, 2010b.

able only if the turn back to LGA was initiated within approximately 10 seconds after the incident. Runways 13 and 22 were reachable for another 10 seconds, indicating that the pilot (or autopilot if available) did in fact have to initiate the return to LGA no more than approximately 20 seconds after thrust was lost.

We believe that if an automation aid had been available to rapidly compute and share the safe glide trajectory back to LGA, and if datalink coordination with air traffic control had been possible to facilitate clearing LGA departure traffic, Flight 1549 could have returned to LGA and avoided the very high-risk (albeit successful in this case) water landing. In short, this simple, provably correct “glide to landing” planning tool represents a substantial, technologically sound improvement over the level of autonomous emergency flight management available today and is a step toward the more ambitious goal of fully autonomous flight management.

CERTIFICATION OF FULLY AUTONOMOUS OPERATION

Every year the FAA is asked to certify a wide variety of unmanned aircraft for flight in the NAS. Although most unmanned operations are currently conducted over remote regions where risks to people and property are minimal, certification

is and must continue to be based on guarantees of correct responses in nominal conditions, as well as contingency management to ensure safety. Although redundancy will continue to be key to maintaining an acceptable level of risk of damage to people and property in the event of failures, for UAS aircraft, triple redundancy architecture as is present in commercial transport aircraft may not be necessary because ditching the aircraft is often a viable option.

Safety certification is a difficult process that requires some trust in claims by manufacturers and operators about aircraft design and usage. Automation algorithms, however, can ultimately be validated through rigorous mathematical and simulation-based verification processes to provide quantitative measures of robustness, at least for envisioned anomalies in weather, onboard systems, and traffic.

Addressing Rigidity in Flight Management Systems

The remaining vulnerability of a fully autonomous UAS FMS is its potential rigidity, which could lead to an improper response in a truly unanticipated situation. The default method for managing this vulnerability has been to insert a human pilot into the aircraft control loop. However, with remote operators who have limited engagement with the aircraft, human intervention may not be the best way to offset automation rigidity. If that is the case, the certification of fully autonomous UAS FMS must be based on meeting or exceeding human capabilities, although assessing the human capacity for response will be challenging.

For remote unmanned aircraft, we can start by characterizing the bounds on user commands. Formal methods of validating and verifying automation algorithms and their implementations, as well as assessing their flexibility (rigidity), will also be essential. Simulation and flight testing will, of course, be necessary to gain trust, but we propose that simulation should be secondary to formal proofs of correctness when assessing the performance, robustness, and ultimately safety of autonomous UAS.

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, fully autonomous UAS operation will be both technologically feasible and safe. The only remaining issue will be overcoming public perceptions and lack of trust, which we believe can be mitigated by long-term exposure to safe and beneficial UAS operations.

REFERENCES

Atkins, E. 2010a. Aerospace Avionics Systems. Chapter 391 in Encyclopedia of Aerospace Engineering, edited by R. Blockey and W. Shyy. New York: Wiley

Atkins, E. 2010b. Emergency Landing Automation Aids: An Evaluation Inspired by US Airways Flight 1549. Presented at the AIAA Infotech@Aerospace Conference, Atlanta, Georgia, April 2010.

Atkins, E., A. Khalsa, and M. Groden. 2009. Commercial Low-Altitude UAS Operations in Population Centers. Presented at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) Aircraft Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, Hilton Head, South Carolina, September 2009.

Beard, R. 2010. Embedded UAS Autopilot and Sensor Systems. Chapter 392 in Encyclopedia of Aerospace Engineering, edited by R. Blockey and W. Shyy. New York: Wiley.

Choi, H., E. Atkins, and G. Yi. 2010. Flight Envelope Discovery for Damage Resilience with Application to an F16. Presented at the AIAA Infotech@Aerospace Conference, Atlanta, Georgia, April 2010.

Fishbein, S.B. 1995. Flight Management Systems: The Evolution of Avionics and Navigational Technology. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger.

Kwatny, H., J. Dongmo, B. Cheng, G. Bajpai, M. Yawar, and C. Belcastro. 2009. Aircraft Accident Prevention: Loss-of-Control Analysis. In Proceedings of the Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Chicago, Ill., August 2009. Reston, Va.: AIAA.

Liden, S. 1994. The Evolution of Flight Management Systems. Pp. 157–169 in Proceedings of the IEEE Digital Avionics Conference. New York: IEEE.

McClamroch, N.H. In press. Steady Aircraft Flight and Performance.

Tang, L., M. Roemer, J. Ge, A. Crassidis, J. Prasad, and C. Belcastro. 2009. Methodologies for Adaptive Flight Envelope Estimation and Protection. In Proceedings of the Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, AIAA, Chicago, Ill., August 2009. Reston, Va.: AIAA.

Weber, R., and E. Euteneuer. 2010. Avionics to Enable UAS Integration into the NextGen ATS. Presented at AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Toronto, Ontario, August 2010.

Yi, G., and E. Atkins. 2010. Trim State Discovery for an Adaptive Flight Planner. Presented at the Aerospace Sciences Meeting, AIAA, Orlando, Fl., January 2010.