D

Methods and Results from the AHRQ-Tufts Evidence-Based Report on Vitamin D and Calcium

The purpose of this systematic evidence-based review, referred to as AHRQ-Tufts,1 requested by the Office of Dietary Supplements/National Institutes of Health, the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, and the Food and Drug Administration and conducted by the Tufts Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC), was to answer key scientific questions on how dietary vitamin D and calcium intake effect health outcomes. The key questions addressed in the AHRQ-Tufts reports are as follows:

Key Question 1. What is the effect of vitamin D, calcium, or combined vitamin D and calcium intakes on clinical outcomes, including growth, cardiovascular diseases, body weight outcomes, cancer, immune function, pregnancy or birth outcomes, mortality, fracture, renal outcomes, and soft tissue calcification?

Key Question 2. What is the effect of vitamin D, calcium, or combined vitamin D and calcium intakes on surrogate or intermediate outcomes, such as hypertension, blood pressure, and bone mineral density?

Key Question 3. What is the association between serum 25(OH)D concentrations or calcium balance and clinical outcomes?

Key Question 4. What is the effect of vitamin D or combined vitamin D and calcium intakes on serum 25(OH)D concentrations?

Key Question 5. What is the association between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and surrogate or intermediate outcomes?

The review focused on electronic searches of the medical literature (1969–April 2009) to identify publications addressing the aforementioned questions. One hundred and sixty-five primary articles and 11 systematic reviews that incorporated more than 200 additional primary articles were systematically reviewed, and each was rated on quality and used to assess the strength of evidence for each outcome.

The methods and results chapters of the AHRQ-Tufts evidence review are reprinted below. The report in its entirety, including appendices and evidence tables, can be accessed and viewed at http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tp/vitadcaltp.htm.

Chapter 2.

Methods

Overview

This report is based on a systematic review of key questions on the relationships between vitamin D [either 25(OH)D concentrations or supplements] or dietary calcium intake, and health outcomes. The methodologies employed in this evidence report generally follow the methods outlined in the AHRQ Methods Reference Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/repFiles/2007_10DraftMethodsGuide.pdf). The initial questions identified by the federal sponsors of this report were refined with input from a Technical Expert Panel (TEP). This report does not make clinical or policy recommendations. The report is being made available to an IOM committee charged with updating vitamin D and calcium DRIs.

A description of roles and responsibilities of sponsoring federal agencies, AHRQ, the TEP and the EPC is included to clarify the relationships that support the process and ensure transparency and that the approach adhered to the highest standards of scientific integrity.

Because of the large number of abbreviations for unfamiliar terms are used, their explanations have been repeated whenever deemed necessary. A table of Abbreviations can be found after the references in page 316. We also provide a table with the latitudes of several major cities in Central and North America, right after the Abbreviations table, on page 320.

Sponsoring federal agencies

The sponsoring agencies were responsible for specifying the topic-specific task order requirements. They participated in a Kick-Off meeting with the EPC and the Task Order Officer (TOO) to facilitate a common understanding of the topic-specific work requirements, and responded to inquiries from the TOO if modifications to the work order were requested by the EPC. Any communication between the sponsoring agencies and the EPC occurred with oversight from the TOO.

Review by Federal sponsors was limited to comments on factual errors, requests for clarification, and consistency with the original contract task order. Comments on the scientific content of the report were not provided. In all cases, reviewer comments are advisory only and are not binding on the scientific authors of the final report.

AHRQ Task Order Officer (TOO)

The TOO was responsible for overseeing all aspects of this Task Order. The TOO served as the point person for all communication required between the sponsoring agencies, the EPC, and other AHRQ officials. The purpose of this communication was to facilitate a common understanding of the task order requirements among the sponsors, the TOO, and the EPC, resolve ambiguities and to allow the EPC to focus on the scientific issues and activities.

Technical Expert Panel (TEP)

The TEP is comprised of qualified experts including, but not limited to, individuals with knowledge of DRI decision making processes, vitamin D and calcium nutrition and biology across the life cycle, health outcomes of interest, and the methodology of conducting systematic reviews. The EPC worked closely with the TEP in the formative stages of the project on question

refinement and throughout the evidence review process to address questions that occurred. The EPC conducted the actual systematic review of the questions independent of the TEP and other stakeholders. It was specified, a priori, that external peer reviewers of the final report could not also serve as a member of the IOM’s calcium and vitamin D DRI Committee.

Those serving on the TEP provided input on such factors as reviewing search terms to ensure they were adequately inclusive, assessing search strategies to ensure they comprehensively covered the questions of interest, and answering questions about technical details (e.g., nuances of laboratory methods of performing an assay). Members of the TEP did not participate in EPC research meetings or in reviewing and synthesizing evidence. Their function was limited to providing domain-specific knowledge and advising the proper context that is relevant to the process of evaluating DRI. They did not have any decision making role and did not participate in writing any part of the evidence report.

EPC methodologists

This evidence report was carried out under the AHRQ EPC program, which has a 12-year history of producing over 175 evidence reports and numerous technology assessments for various users including many federal agencies. EPCs are staffed by experienced methodologists who continually refine approaches to conducting evidence reviews and develop new methods on the basis of accumulated experience encompassing a wide range of topics. The Tufts EPC has produced many evidence reports on nutrition topics19-24 (http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcix.htm). We have also conducted methodological research to identify the issues and challenges of including evidence-based methods as a component of the process used to develop nutrient reference values, such as the DRI, using vitamin A as an example.3

Development of the analytic framework and refinement of key questions

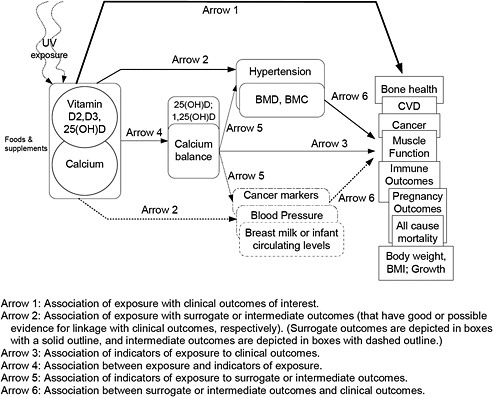

The focus of this report is on the relationship of vitamin D only, calcium only, and combinations of vitamin D and calcium with specific health outcomes. Key questions and analytic frameworks were developed by defining each box in the generic analytic framework described in Chapter 1 with specific reference to vitamin D and calcium.

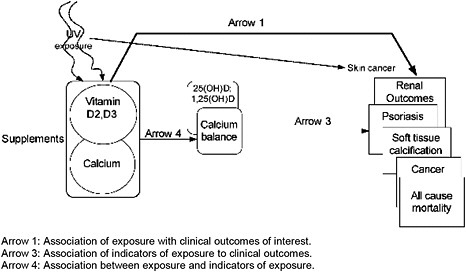

A one-day meeting of the federal sponsors, TEP and Tufts EPC staff was held in Boston on September 20, 2008. At this meeting, the analytic framework was discussed, the key questions refined, and study eligibility criteria established. Two analytic frameworks were developed: one for intakes of vitamin D and/or calcium related to their beneficial effects and one for intakes associated with adverse effects (Figures 3 & 4). We used the PI(E)CO method to establish study eligibility criteria. This method defines the Population, Intervention (or Exposure in the case of observational studies), Comparator, and Outcomes of interest. Details are described in the sections that follow.

Figure 4. Analytic framework for vitamin D and/or calcium safety-related (adverse) outcomes

Definitions

Vitamin D and calcium exposures

Vitamin D exposure included intake of vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 from foods and supplements, including human milk and commercial infant formulas. Because the primary source of vitamin D in the human body is produced in skin exposed to sunlight, background information on ultraviolet B (UVB) exposure was captured to the extent possible. However, we did not include studies that evaluated the effect of or association between exposure to sunlight (or UVB) and clinical outcomes or serum 25(OH)D concentrations. In other words, we did not investigate sunlight exposure as a proxy for or a source of vitamin D intake. Sunlight exposure was considered only as a potential confounder or effect modifier of associations between vitamin D or calcium and clinical outcomes.

Calcium exposure included intake of calcium from foods and supplements, including calcium-containing antacids, mineral-supplemented water, human milk and commercial infant formulas.

Combined vitamin D and calcium exposure included any relevant combinations of the above.

Clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes are measures of how a person (e.g., a study participant) feels, functions or survives, or a clinical measurement of the incidence or severity of a disease (e.g., diagnosis of disease or change from one disease state to another). Examples of clinical outcomes used in this report are incidence of cancer, cardiovascular events, and preeclampsia. The clinical outcomes of interest in this report are described in the “Specific Outcomes of Interest” section.

Indicators of exposure (nutrient intake)

Indicators of exposure are measures that correlate with dietary intake of a nutrient, such as nutrient biomarkers, nutritional status, or markers of nutritional status.

Indicators of vitamin D exposure (i.e., vitamin D intake and sun exposure) included serum 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D concentrations.

Indicators of dietarycalcium intakes included calcium balance (i.e., calcium accretion, retention, and loss).

Surrogate outcomes

Surrogate outcomes are biomarkers or physical measures that are generally accepted as substitutes for or predictors of specific clinical outcomes.18 Changes induced by the exposure or intervention on a surrogate outcome marker are expected to reflect changes in a clinical outcome. Examples of surrogate outcomes used in this report are bone mineral density (as a surrogate marker of fracture risk) and breast mammographic density (as a surrogate marker of breast cancer risk). The surrogate outcomes of interest in this report are described in “Specific Outcomes of Interest” section.

Intermediate outcomes

Intermediate outcomes are possible predictors of clinical outcomes that are not generally accepted to fulfill the criteria for a surrogate outcome. However, in the absence of data for surrogate outcomes, intermediate markers are often used. Examples of intermediate markers used in this report are prostate cancer antigen (as a marker of prostate cancer risk) and blood pressure (as a marker of stroke risk). All intermediate markers of interest in this report are described in “Specific Outcomes of Interest” section.

Life stages

In consultation with the TEP, the 22 life stages defined by the FNB/IOM for the development of DRI were consolidated to 9 categories to facilitate the reporting of results. Within each life stages, men and women (or boys and girls) were considered separately when possible. There are also some inevitable overlaps between these categories. For example, most women in 51-70 years life stage are postmenopausal women. The 9 categories created for this report are:

-

0 – 6 months

-

7 months – 2 years

-

3 – 8 years

-

9 – 18 years

-

19 – 50 years

-

51 – 70 years

-

≥71 years

-

Pregnant and lactating women

-

Postmenopausal women

In summarizing studies for each given outcome, we used our best judgment to describe the study results for each applicable life stage.

Key questions

In agreement with the TEP, the following key questions were addressed in this evidence report. It was decided that arrow 6 in the analytic framework (What is the relationships between intermediate or surrogate outcomes and clinical outcomes?) is outside the scope of the DRI literature review in this report. All outcomes of interest in this report are described in “Eligibility Criteria” section.

Key Question 1. What is the effect of vitamin D, calcium, or combined vitamin D and calcium intakes on clinical outcomes, including growth, cardiovascular diseases, weight outcomes, cancer, immune function, pregnancy or birth outcomes, mortality, fracture, renal outcomes, and soft tissue calcification? (Arrow 1)

Key Question 2. What is the effect of vitamin D, calcium or combined vitamin D and calcium intakes on surrogate or intermediate outcomes, such as hypertension, blood pressure, and bone mineral density? (Arrow 2)

Key Question 3. What is the association between serum 25(OH)D concentrations or calcium balance and clinical outcomes? (Arrow 3)

Key Question 4. What is the effect of vitamin D or combined vitamin D and calcium intakes on serum 25(OH)D concentrations? (Arrow 4)

Key Question 5. What is the association between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and surrogate or intermediate outcomes? (Arrow 5)

Literature search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search to address the key questions. For primary studies, the EPC used the Ovid search engine to conduct searches in the MEDLINE® and Cochrane Central database. A wide variety of search terms were used to capture the many potential sources of information related to the various outcomes (see Appendix A). Search terms that were used to identify outcomes of interest, for both EARs and ULs, can be categorized into the following groups: 1) bodyweight or body mass index; 2) growth (height and weight); 3) fracture or bone mineral density; 4) falls or muscle strength; 5) cardiovascular diseases; 6) hypertension or blood pressure; 7) cancer or neoplasms, including adenomas, colon polyps, and mammography; 8) autoimmune diseases (e.g., type 1 diabetes, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn's disease); 9) preeclampsia, eclampsia and pregnancy-related hypertension; 10) preterm or low birth weight; 11) breast milk or lactation; 12) death; 13) infectious diseases; 14) soft tissue calcification (for ULs only); and 15) kidney disease or hypercalcemia (for ULs only). The different outcomes were crossed with terms to identify vitamin D and calcium exposure: “vitamin D”, “plasma vitamin D”, “25-hydroxyvitamin D” and its abbreviations, “25-hydroxycholecalciferol”, “25-hydroxyergocalciferol”, “calcidiol”, “calcifediol”, “ergocalciferol”, “cholecalciferol”, “calciferol”, “calcium”, “calcium carbonate”, “calcium citrate”, “calcium phosphates” and

“calcium malate”. Literature searches of the outcomes alone without references to vitamin D or calcium were not conducted.

The searches were limited to human studies, English language publications, and citations from 1969 to September 2008 for all but bone outcomes. For outcomes related to bone health (i.e., bone mineral density, fracture, fall or muscle strength), we relied on a recent comprehensive systematic review performed by the Ottawa EPC.6 The Ottawa EPC report was updated from January 2006 to September 2008. The electronic search was supplemented by bibliographies of relevant review articles. Unpublished data, including abstracts and conference proceedings, were not included. An updated literature search was performed in April 2009 for all the topics to include relevant primary studies published since September 2008 for the final report.

For potentially relevant systematic reviews, we also searched MEDLINE®, the Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, and the Health Technology Assessments database up to December 2008. We searched for systematic reviews of the relationships between vitamin D or calcium and the prespecified outcomes. In this search, terms for identifying vitamin D or calcium exposures were crossed with terms for identifying systematic reviews, such as “systematic,” “evidence,” “evidence-based,” “meta-analysis,” or “pooled analysis”; specific terms for the outcomes were not included (Appendix B).

Study selection

Abstract screening

All abstracts identified through the literature search were screened. Eligible studies included all English language primary interventional or observational studies that reported any outcome of interest in human subjects in relation to vitamin D and/or calcium.

Full text article eligibility criteria

Articles that potentially met eligibility criteria at the abstract screening stage were retrieved and the full text articles were reviewed for eligibility. Rejected full text articles were examined only once, unless the articles were equivocal for inclusion or exclusion. In that event, the article in question was examined again by a different reviewer and a consensus was reached after discussion with the first reviewer. We recorded the reason for rejection of all full text articles.

Primary studies

Because the outcomes of interest ranged from very broad topics with common occurrences (e.g., cardiovascular disease) to narrowly focused topics with relatively few occurrences (e.g., preeclampsia), the number and types of studies available for each outcome varied widely in the distribution of study designs and sample sizes. It was neither possible nor desirable to use a uniform, strict set of inclusion and exclusion criteria applicable to all outcomes. Therefore, additional eligibility criteria germane to the specific outcome were applied to all accepted full text articles. Details are described in the “Eligibility criteria” section.

General eligibility criteria for the full text articles were:

Population of interest:

-

Primary population of interest is generally healthy people with no known disorders

-

Studies that include a broad population that might have included some people with diseases. For example, some hypertensive and diabetic patients were included.

-

People with prior cancers (or cancer survivors), prior fractures, and precancer conditions (e.g., colon polyps) were included

-

Studies that enrolled more than 20% subjects with any diseases at baseline were excluded. An exception was made for older adults (mean age ≥65 years old) due to high prevalence of diseases in this population. For studies of older adults, only studies that exclusively enrolled subjects with particular disease (e.g., 100% type 2 diabetes) were excluded. In addition, for studies of blood pressure, studies of people exclusively with hypertension were included.

-

For adverse or safety outcomes, we included any adverse effects of high intake in any population.

Intervention/exposure of interest

-

For observational studies:

-

Serum 25(OH)D or 1,25(OH)2D concentration

-

Dietary intake level of vitamin D were not included due to inadequacy of nutrient composition tables for vitamin D.25

-

Dietary intake level of calcium from food and/or supplements

-

Calcium balance (i.e., calcium accretion, retention, and loss)

-

-

For interventional studies:

-

Vitamin D supplements (but not analogues) with known doses

-

Calcium supplements with known doses

-

The only combination of dietary supplements of interest was the combination of vitamin D and calcium. Any other combinations of supplements and/or drug treatments were excluded unless the independent effects of vitamin D and/or calcium can be separated. Thus studies of multivitamins were excluded.

-

Trials in which participants in both study groups took the same calcium (or vitamin D) supplement were evaluated as vitamin D (or calcium) versus control trials. In other words, the intervention common to both study groups was ignored (though it was noted).

-

Food based interventions were included if the doses of vitamin D and/or calcium were quantified and there were differences in the doses between the comparison groups. For example, a trial of dairy supplementation (with 500 mg/d calcium) versus no supplementation was qualified to be included. However, a trial of calcium fortified orange juice (with 1200 mg/d calcium) versus milk (with 1200 mg/d calcium) was not qualified to be included because there are no differences in the calcium doses.

-

Nonoral routes of nutrient delivery were excluded

-

Specific Outcomes of interest

-

Growth outcomes

-

In infants and premenarchal girls and boys of corresponding age: weight and height gain

-

-

Cardiovascular disease clinical outcomes

-

Cardiac events or symptoms (e.g., myocardial infarction, angina)

-

-

-

Cerebrovascular events (stroke, transient ischemic attacks)

-

Peripheral vascular events or symptoms (diagnosis, claudication)

-

Cardiovascular death

-

Study-specific combinations of cardiovascular events

-

-

CVD intermediate outcomes

-

Diagnosis of hypertension

-

Blood pressure

-

-

Weight outcomes

-

In adults only: incident overweight or obesity, body mass index, or weight (kg)

-

-

Cancer (incident or mortality)

-

Cancer from all cause (or total cancer)

-

Prostate

-

Colorectal cancer

-

Breast cancer

-

Pancreatic cancer

-

Cancer-specific mortality

-

-

Cancer intermediate outcomes

-

Colorectal adenoma

-

Aberrant cryptic

-

Breast mammographic density (quantitative whole breast density)

-

-

Immune function clinical outcomes

-

Infectious diseases

-

Autoimmune diseases

-

Infectious disease-specific mortality

-

-

Pregnancy-related outcomes

-

Preeclampsia

-

High blood pressure with or without proteinuria

-

Preterm birth or low birth weight

-

Infant mortality

-

-

Mortality, all cause

-

Bone health clinical outcomes

-

Rickets

-

Fracture

-

Fall or muscle strength

-

-

Bone health intermediate outcomes

-

Bone mineral density or bone mineral content

-

-

Dose-response relationship between intake levels and indicators of exposure (arrow 4 of Figures 2 and 3)

-

Serum 25(OH)D concentration

-

Breast milk or circulating concentrations of 25(OH)D in infants

-

-

Outcomes of tolerable upper intake levels (ULs)

-

All-cause mortality

-

Cancer and cancer-specific mortality

-

Renal outcomes

-

Soft tissue calcification

-

Adverse events from vitamin D and/or calcium supplements

-

Study design

-

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

-

Nonrandomized, prospective comparative studies of interventions

-

Prospective, longitudinal, observational studies (where the measure of exposure occurred before the outcome)

-

Prospective nested case-control studies (case-control study nested in a cohort so the measure of exposure occurred before the outcome)

-

We excluded cross-sectional studies and traditional, retrospective case-control studies (where the measure of exposure occurred after or concurrent with the outcome)

Systematic reviews

We included relevant systematic reviews that addressed the key questions. Systematic review is defined as a study that has at a minimum the following three components: a statement of the research questions (aims or objectives); a description of the literature search; and a listing of the study eligibility criteria. We did not attempt to contact authors for clarifications of outstanding questions. In addition, the following types of reviews were excluded: reviews of foods or diets that did not quantify vitamin D or calcium intake; reviews that included nonoral routes of nutrient delivery; reviews that did not evaluate the association between vitamin D or calcium intake to health outcomes; reviews of nonhuman data; and pooled analyses of primary databases (i.e., secondary database analyses of multiple cohorts) that did not include a systematic review (except possibly as a replacement for data from the original cohorts).

To determine the relevance of a systematic review to this report, the following inclusion criteria were applied:

-

Address key question(s) of interest (i.e., similar PI(E)CO criteria used):

-

Systematic review must include only healthy population at baseline or have separate analyses for population with diseases and without diseases.

-

Systematic reviews of interventional studies had to include only vitamin D or calcium interventions. Cointerventions with other nutrients had to be disallowed or separate analyses were needed for studies of vitamin D or calcium interventions alone.

-

Systematic review of observational studies had to report the baseline concentrations of serum 25(OH)D and the assay methods used or the dietary assessment methods used to measure dietarycalcium intake (e.g. food frequency questionnaire, 24 hour recall).

-

Exposure levels (e.g., level of 25(OH)D or calcium intake) or doses of interventions had to be reported

-

Outcome definitions had to be reported

-

Designs of primary studies had to be reported. If cross-sectional or case-control studies were included, the systematic review must provide sufficient information or separate analyses to separate them from RCTs or cohort studies.

-

-

We include only the most recent update if there were multiple systematic reviews from the same group of investigators using the same review process.

-

Where there were several systematic reviews on the same topic with similar conclusions and the same set of primary studies, we selected the systematic review with either the latest cutoff date for the end of the literature search or the most included primary studies. Where there were several systematic reviews, each of which included only a sample of

-

the total literature included by the several systematic reviews, all systematic reviews were included.

Other specific eligibility criteria

-

Growth outcomes (weight and height gain)

-

Only infants (<1 year old) and children (age <18 years old) were included

-

For infants, we include all eligible study designs. The vitamin D and/or calcium intervention or exposure can be administered to the mothers or to the infants in the study.

-

For infants, premenarchal girls, and boys of similar age, only RCTs that reported weight as a primary or secondary outcome were included. RCTs of weight loss were excluded.

-

-

Cardiovascular disease clinical outcomes

-

Only adults (aged ≥18 years old) were included.

-

-

Blood pressure and bodyweight

-

Only adults (aged ≥18 years old) were included.

-

Only RCTs of calcium or vitamin D interventions were included. We did not include observational studies of associations between calcium or vitamin D intake or serum vitamin D concentrations and blood pressure or weight measurements (as continuous outcomes). This decision was made in agreement with the TEP in part because it was agreed that any conclusions based on observational studies (e.g., associations between baseline calcium intake and change in systolic blood pressure) would be weak and difficult to interpret.

-

-

Bone health clinical outcomes

-

The Ottawa EPC report6 was updated with literature published between January 2006 and September 2008. Only RCTs qualified for inclusion.

-

Studies of calcium and bone health clinical outcomes were excluded.

-

-

Bone health intermediate outcomes

-

The Ottawa EPC report6 was updated with literature published between January 2006 and September 2008. For adults, we included only BMD indices. For children, we included only BMC indices. Only RCTs with duration of more than 1 year were qualified for inclusion.

-

Studies of calcium and bone health clinical outcomes were excluded.

-

-

Dose-response relationship between intake levels and indicators of exposure (arrow 4 of Figures 2 and 3)

-

Studies for this question were identified in our literature search that crossed vitamin D terms with various outcomes terms. Some studies that addressed this question but do not report any of the outcomes of interest would not have been identified in this manner. Because the availability of serum 25(OH)D concentration is unlikely to be adequately indexed in the Medline citation, it would be difficult to comprehensively search the literature for this question. To do so would require retrieving all full text articles mentioning vitamin D supplements (in excess of 10,000) to look for data on serum 25(OH)D concentration.

-

-

-

Only RCTs were included for this question. However, RCTs of different regimens but the same dose of vitamin D supplementation were excluded (e.g., comparison of daily, weekly versus monthly dose).

-

Data extraction

For outcomes that had not been subjected to a prior systematic review, we extracted and summarized the relevant data from the primary studies. Where previous systematic reviews were available, we summarized their results into our report. In addition, we updated the previous systematic reviews (with our eligibility criteria) and extracted and summarized the additional primary studies.

Data extraction forms (evidence tables) were developed separately for extraction of systematic reviews and primary studies. For primary studies, the items extracted were: study characteristics, baseline population characteristics, background diet data, dietary assessment methods for calcium intake, 25(OH)D assay methods, interventions (for interventional studies only), confounders and effect modifiers that were adjusted for in statistical analysis, results, and quality assessments. Whenever the type of vitamin D supplement (D2 or D3) was clearly reported, we extracted and reported this information. Otherwise, we used the general term “vitamin D”. Evidence tables for all eligible studies are available in Appendix C. For systematic reviews, items extracted were: design, population, intervention (exposure) and comparator, results, and AMSTAR26 checklist criteria (a measurement tool created to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews). A table with a list of all systematic reviews with the evaluation of their relevance to this report, and evidence tables of the qualified systematic reviews are available in Appendix D.

Data analysis

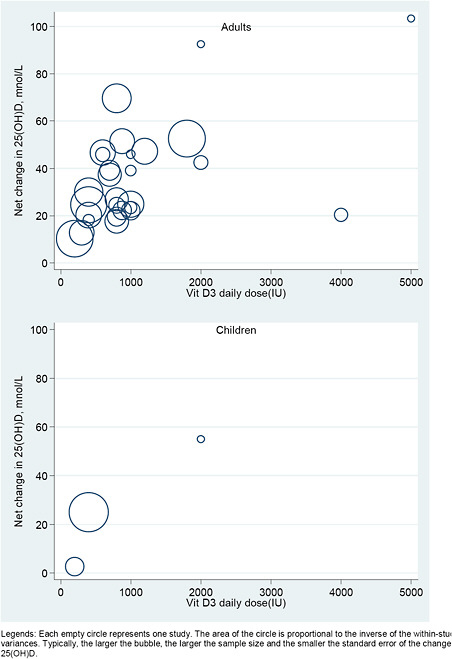

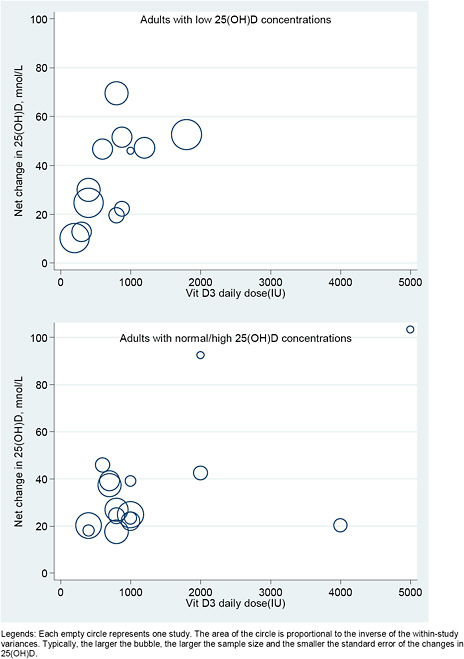

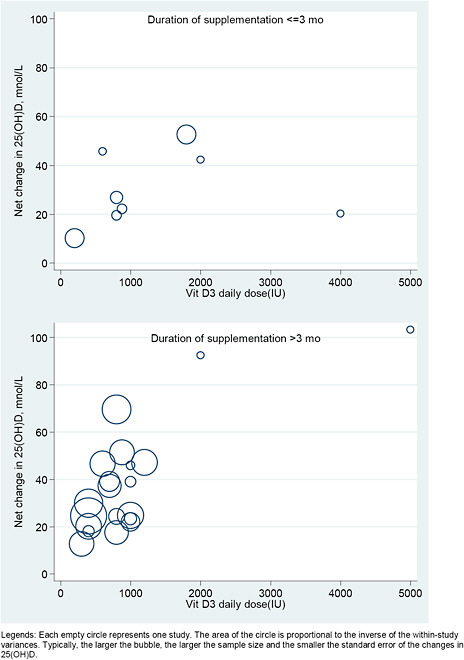

We explored the dose-response relationship between the level of intake of vitamin D (with or without calcium) and serum 25(OH)D concentrations graphically, using a scatter (“bubble”) plot. We plotted the observed net changes in 25(OH)D concentration, against the doses of vitamin D supplementation. In these plots studies were represented by empty circles (bubbles) with area proportional to the inverse of the within-study variances. Typically, the larger the bubble, the larger the sample size and the smaller the standard error of the changes in 25(OH)D.

Studies were included only if they reported sufficient data to estimate both mean net change and SE of the net change. We required data on both the mean net change in outcome level and the SE of the change. However, many studies provided only the SEs for the baseline and final outcome levels. In order to include these studies in the analyses we had to make several assumptions to estimate the SE of the change. To do this we used the

where SE1, SE2, and SE12 are the SEs for baseline, final and change, respectively, and ρ is the correlation between the baseline and final measurements.27 We arbitrarily chose the correlation, ρ, to be 0.50, the midpoint value. In our experience, using different values for ρ generally does not greatly affect the meta-analysis results of quantitative analyses or conclusions.

For each RCT, the SE of the net change was then calculated using the standard calculation for determining the SE of 2 independent cohorts. Namely, in the above equation where the correlation factor becomes 0, and thus the final term drops out. Where studies reported either within-cohort SEs or net change SEs, these numbers were used. Some RCTs may have more than

two arms (e.g., two different doses of vitamin D supplement compared to the placebo), and in this case, the same control arm was used to calculate the net change and the SE of the net change as for two independent comparisons.

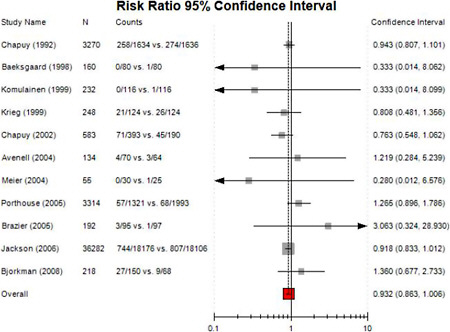

Meta-analysis

Overall, we did not perform new meta-analyses in this report because of large degree of clinical and methodological heterogeneity across studies. However, we reanalyzed an existing meta-analysis using available data in the all-cause mortality section. We performed random effects model meta-analyses of risk ratios using the DerSimonian and Laird model.28 The random effects model assigns a weight to each study that is based both on the individual study variance and the between-study heterogeneity. Compared with the fixed effect model, the random effects model is more conservative in that it results in broader confidence intervals when hen between-study heterogeneity is present. We tested for heterogeneity using Cochran’s Q (considered significant for P <0.10) and quantified its extent with I2 29,30. I2 ranges between 0 and 100% and quantifies the proportion of between-study variability that is attributed to heterogeneity rather than chance.

Intercooled Stata SE version 9.2 and Meta-Analyst version 3.2 (developed by Tufts EPC) were used for analyses. All P values are two tailed and considered significant when less than 0.05, unless otherwise indicated.

Grading of studies analyzed in this evidence report

Studies included as part of accepted in this report have been designed, conducted, analyzed, and reported with various degrees of methodological rigor and completeness. Deficiencies in any of these items may lead to biased reporting or interpretation of the results. While it is desirable to have a simple evidence grading system using a single quantity, the quality of evidence is multidimensional. A single metric cannot adequately capture information needed to interpret a study. Not withstanding these limitations, providing an indication of study quality adds an important dimension to the summary of published data.

We note that we did not grade the strength of evidence per outcome. Grading the strength of the evidence considers several dimensions beyond the methodological quality of the individual studies. These include but are not limited to consistency of studies, directness, precision, as well as judgments on whether conclusions are affected by systematic errors and biases.

Critical appraisal and grading of primary studies

Critical appraisal of the evidence is an important aspect of conducting a systematic review. For the assessment of interventional studies, the criteria were based on the CONSORT31 statement for reporting RCTs (a checklist with specifications for reporting important aspects of a trial). We primarily considered the methods used for randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding as well as the use of intention-to-treat analysis, the report of well-described valid primary outcomes, and the dropout rate.

For interventional studies with nonrandomized design, we used the report of eligibility criteria and assessed the adequacy of controlling for differences between compared groups in terms of baseline characteristics and prognostic factors. We also considered the reporting of

intention-to-treat analyses and crossovers when so designed, as well as important differential loss to followup between the compared groups or overall high loss to followup. The validity and the adequate description of outcomes and results were re also assessed.

For the assessment of prospective cohorts and nested case-control studies (crosssectional and retrospective case-control studies were excluded from this review), we developed a rating checklist specifically designed for nutritional epidemiology study based on some of the reporting items for cohort study in STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) checklist32 and the nutrition-specific items in our previous publication.33 Items assessed include: eligibility criteria and sampling of study population, blinding of exposure and outcome assessors, dietary assessment methodology (when applicable), assay methodology of biomarkers of intake (when applicable), clear reporting of comparisons in the study, statistical analyses, adequacy of controlling for baseline characteristics and prognostic factors (including confounders), clear reporting of outcome definitions, and prospective study design with preplanned hypotheses.

The quality assessment checklists for intervention or observational studies can be found in Appendix E. Additional considerations that were not included in the checklists are described later in this section.

In this report we adapted a three-category grading system of the AHRQ Methods Reference Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Note that a single study can receive different grades for different outcomes. This system defines a generic grading system that is applicable to each type of study design including interventional and observational studies:

A

Studies have the least bias and results are considered valid. These studies adhere mostly to the commonly held concepts of high quality including the following: a formal study design; clear description of the population, setting, interventions, and comparison groups; appropriate measurement of outcomes; appropriate statistical and analytic methods and reporting; no reporting errors; less than 20 percent dropout; clear reporting of dropouts; and no obvious bias. Studies must provide valid estimation of nutrient exposure, from dietary assessments and/or biomarkers with reasonable ranges of measurement errors, and justifications for approaches to control for confounding in their design and analyses.

B

Studies are susceptible to some bias, but not sufficient to invalidate the results. They do not meet all the criteria in category “A”, they have some deficiencies but none likely to cause major bias. The study may be missing information, making it difficult to assess limitations and potential problems.

C

Studies have significant bias that may invalidate the results. These studies have serious errors in design, analysis, or reporting; there are large amounts of missing information, or discrepancies in reporting.

If the initial assigned grade was equivocal, then the study received a second round of review by an independent reviewer, and the final grade was reached via consensus. Lastly, it should be noted that the qualitygrading system evaluates and grades the studies within their own design strata (i.e., RCTs, cohorts, nested case-control). It does not attempt to assess the comparative

validity of studies across different design strata. Thus, it is important to be cognizant of the study design when interpreting the methodological quality grade of a study.

Additional considerations of methodological quality of primary studies for the purpose of DRI decision making

Randomized controlled trials of all outcomes

The Tufts EPC debated about the quality assessment of RCTs. A consensus was reached to include additional considerations for RCTs to receive grade A. The general quality assessment of interventional studies as described earlier has been widely adopted for the purpose of grading high quality effectiveness trials (in contrast with a more standardized efficacy trial) which are most relevant to the actual use of supplements. Thus the crossover of interventions (i.e., contamination between supplementation and placebo groups) affects the applicability more than the methodological quality. However, it was the consensus among the Tufts EPC methodologists that the RCTs with contamination between supplementation and placebo groups cannot receive grade A because this issue affects the actual differences in the doses given to the subjects. Therefore it is particularly important when the trial results are used to guide decisions about DRI, as opposed to decisions about whether to actively recommend supplementation for an individual.

Observational studies of cancer outcomes

When cancer cases were identified based on cancer registries or questionnaire-based data, we perused whether the investigators verify the diagnoses independently (e.g., by use of medical records or pathological reports). An observational study of cancer outcomes cannot receive grade A if the cancer diagnoses were not verify independently. We also examined if the study adequately control for other risk factors for specific cancer. We used the suggested risk factors by National Cancer Institute (www.cancer.org). An observational study of cancer outcomes cannot receive grade A if important risk factors for the specific cancer were not fully controlled for in their analyses.

Critical appraisal of systematic reviews

We also critically appraised systematic reviews utilized in this report. However, a summary quality grade for systematic review is difficult to interpret. While it may be straight forward to assign a high quality grade to a rigorously carried out systematic review of high quality primary studies, a rigorously conducted systematic review finding only poor quality primary studies to summarize has uncertain value. Similarly, a poorly conducted systematic review of high quality studies may also result in be misleading conclusions. Therefore, to appreciate its validity, the various dimensions and nuances of the systematic review must be understood.

To help readers appreciate the methodological quality of a systematic review, we applied the AMSTAR checklist,26 a tool that was created for this purpose. This tool does not assign a composite grade. Instead, the items evaluated are made explicit for the reader. Another challenge in evaluating systematic reviews is that none of the existing systematic reviews were specifically conducted to be used for DRI development; therefore their “quality”, for the purpose of DRI development, is impossible to reliably define.

In addition to using AMSTAR, we made comments on special considerations, issues or limitations concerning design, conduct and analyses of the systematic review, and interpretability of the results for the purpose of DRI development.

Reporting of the evidence

Evidence tables

Evidence tables offer a detailed description of the primarys tudies we identified that address each of the key questions. These tables provide detailed information about the study design, patient characteristics, background diet, inclusion and exclusion criteria, interventions (or exposures), comparators used, and outcomes assessed in the study. A study, regardless of how many interventions (or exposures) or outcomes were reported, appears once in the evidence tables. Evidence tables are ordered alphabetically by the first author’s last name to allow for easy searching within the tables. Evidence tables are available electronically in Appendix C.

Summary tables

Summary tables were created to assist (qualitative) synthesis of primary studies of the same outcomes and life stage. If feasible, data were also grouped by sex. Typically, in each outcome section, we presented one summary table for the study characteristics of all included studies, followed by another summary table for study findings.

We created different summary tables for different exposures (i.e., vitamin D or calcium) and for different study designs (i.e., interventional or observational studies). Key study characteristics, such as population characteristics (i.e., health status, age and sex), vitamin D assay method and season in which blood was drawn, dietary assessment methods and whether the instrument was internally validated, patient or participant adherence, and study comparisons, were presented in the summary table for study characteristics. We reported daily vitamin D doses (IU/d) and/or elemental calcium doses (mg/d) in all summary tables.

For observational studies, we also list the confounders adjusted in either design (e.g., matching factors) or analyses. If any confounders or effect modifiers in each prespecified category (i.e., nutrients, demographics, anthropometry, medical conditions, ultraviolet exposure, and life styles) were controlled for, we marked “X” in the category. Otherwise, the category was left blank.

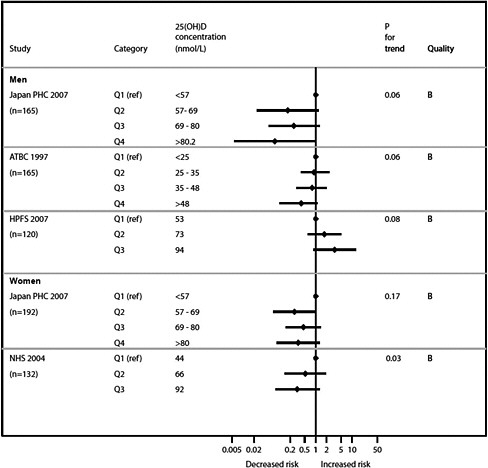

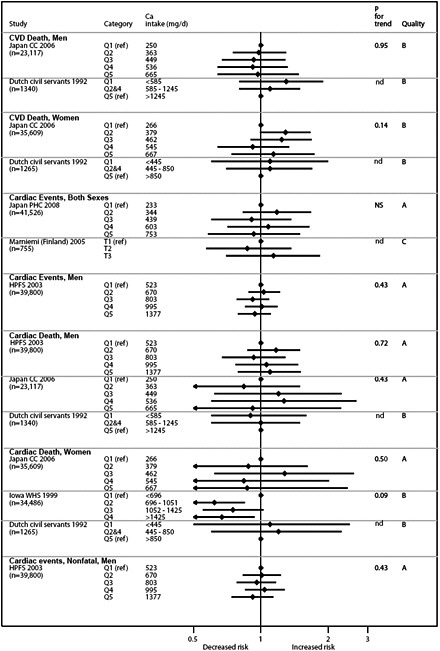

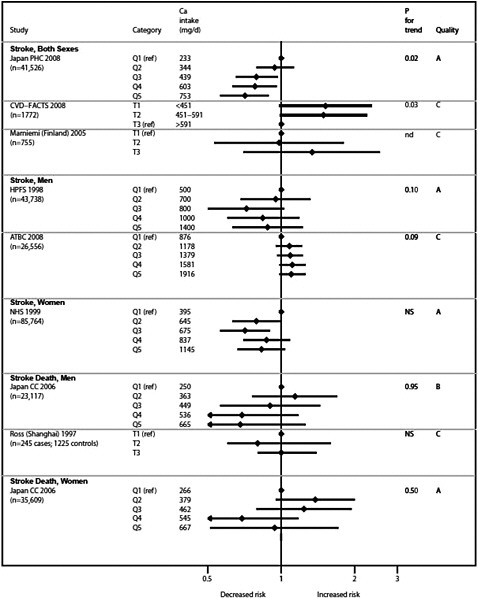

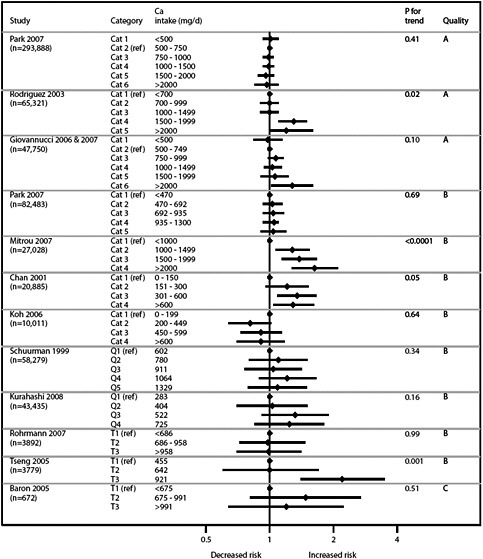

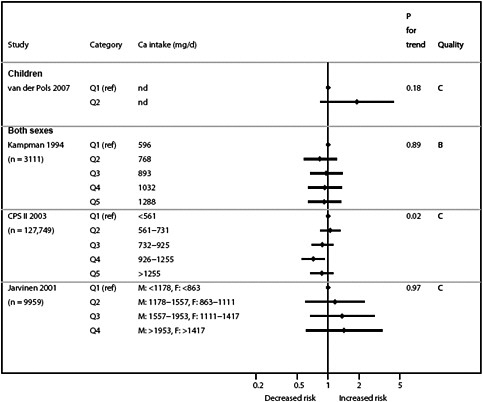

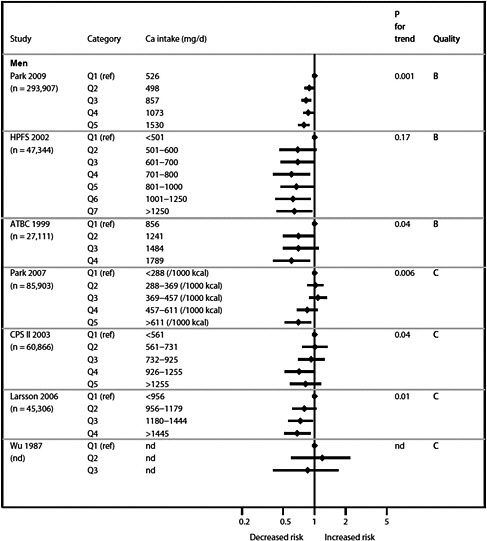

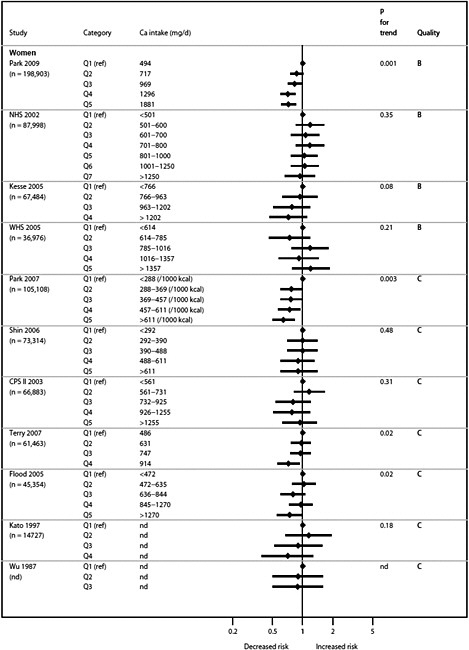

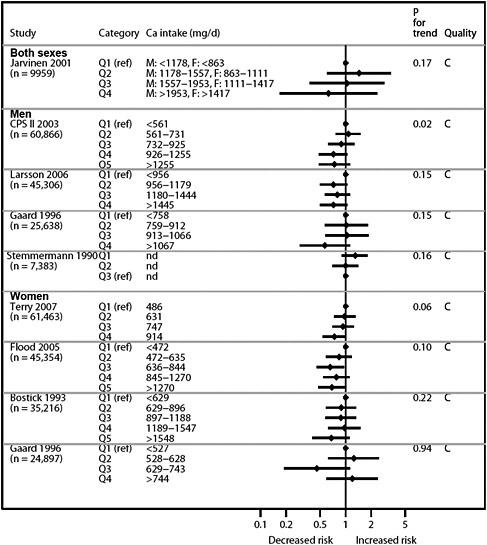

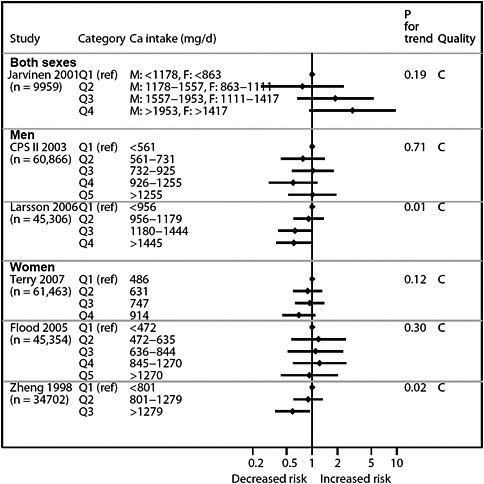

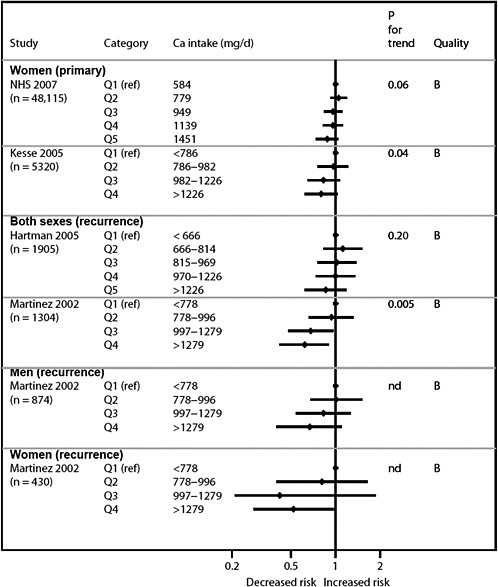

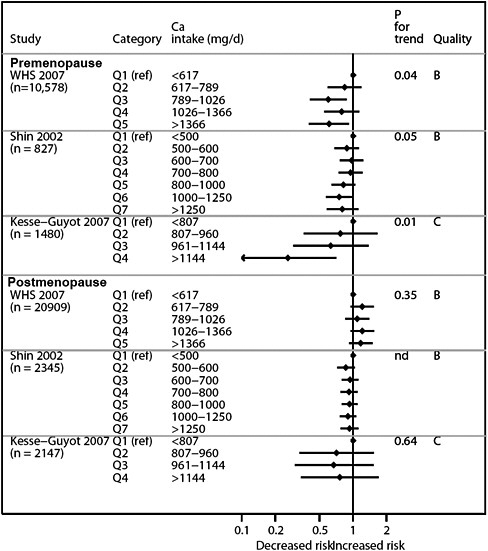

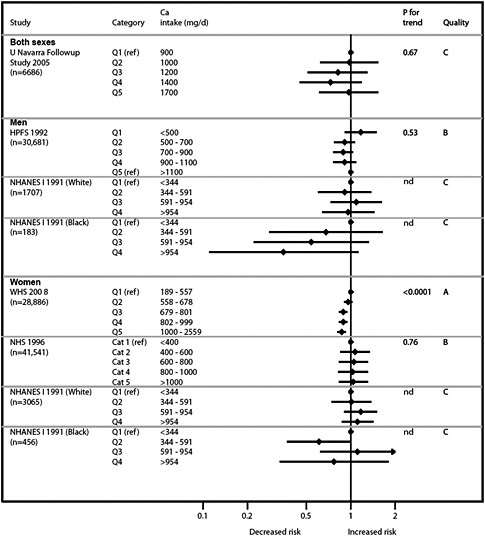

Graphical presentation of dose-response relationship

We present graphically the results of studies associating outcomes with categorical exposures (e.g., percentiles or other arbitrary categories of 25(OH)D concentration or of total calcium intake). The graphs complement the information mentioned in the tables and allow the reader to appreciate the direction of the estimated effects, even when the choice of the reference category is inconsistent across studies. The graphs do not readily convey the slope (strength) of the dose-response relationship between exposure and outcome, because the exposure categories are simply ranked and their spacing does not necessarily correspond to the actual values that they represent within study or across studies.

Grand summary tables (evidence map)

In the beginning of the Results section, we created a grand overview table. The table details how many studies reported an outcome of interest (either as a primary or nonprimary outcome) and also listed the total number of unique studies (including systematic reviews) as each study

may have provided data on more than one outcome. The number of primary studies included in each existing systematic review is also reported.

Units of measurement

In this report, we converted serum 25(OH)D concentrations as reported by various studies as different units (i.e., ng/mL, μg/dL, μg/L and ng/dL) to nmol/L. The conversion formula is 1 ng/mL = 2.5 nmol/L. To limit the variation in the reporting of vitamin D unit (e.g., nmol, IU, μg and mg), IU was chosen as the standard unit and all other units were converted using a standard formula. The conversion formula for micrograms is 1 μg = 40 IU.

Assay method

For 25(OH)D measurements, we present information on the assay used in our evidence tables, and summary tables describing individual studies. When reported, we also recorded details on the methodology or kit used (e.g., RIA–radioimmunoassay, RIA “DiaSorin”) used. Often, additional information was lacking. We did not perform any subgroup analyses based on the type of 25(OH)D assay used.

Sunlight exposure

We report information on country where the study took place and its latitude (when this was meaningful), and when available, the season when serum 25(OH)D concentrations were measured. A substantial amount of vitamin D is formed in the skin in humans. The amount of vitamin D synthesized in the skin depends on a person’s exposure to UV irradiation. Therefore, information on country’s latitude (and season of serum 25(OH)D measurements) informs on whether different populations are likely to have similar or different amount of endogenous vitamin D production. Latitudes were extracted directly from the published reports, or extrapolated from the city or country where the study took place (by searching Google for “<county/city> latitude”). For national or international studies that spanned a wide range of latitudes (e.g., NHANES), the latitude information was summarized simply as "various." To facilitate the reader, we also provide a Table with the latitudes of major cities in Central and North America (this table is found right after the Abbreviations table on page 316.

Primary and secondary outcomes

For intervention studies, we distinguished primary from secondary (or nonspecified) outcomes. Outcomes were considered primary only when they were clearly reported as such or when the outcome was used in an ad hoc sample size calculation. For observational studies we did not separate primary from secondary outcomes. For example, many observational studies are analyses of the same well known cohorts for several different outcomes. Each of these studies may have a different “primary” outcome.

Study quality

We summarize methodological and reporting quality of individual studies and meta-analyses. More details on the reporting characteristics of individual studies and systematic reviews are found in the evidence tables (Appendix C).

Organization of the Results Section

The Results section is organized in the following way:

Chapter 3.

Results

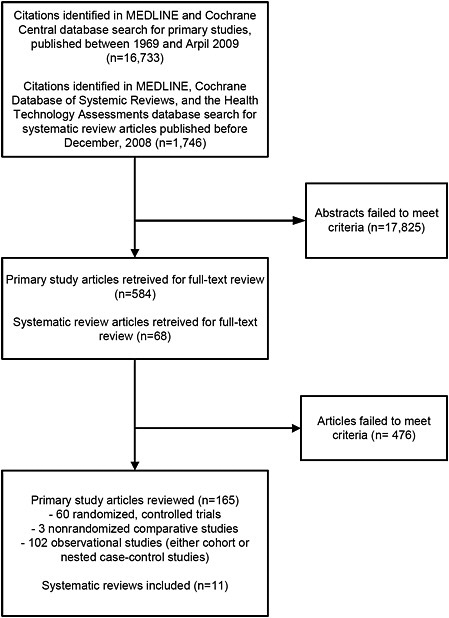

Literature search results

The original MEDLINE® and Cochrane Central database search for primary studies yielded 15,621 citations of generic health outcomes and 194 citations of adverse or safety outcomes. The update search for primary studies published between September, 2008 and April, 2009 yielded 918 citations. We identified 654 of these as potentially relevant and retrieved the full-text articles for further evaluation. Of these, 478 did not meet eligibility criteria (Appendix E); thus, a total of 165 primary study articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report (Figure 5). Of the 165 primary study articles, 60 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 3 were nonrandomized comparative studies, and 102 were observational studies (either cohort or nested case-control studies). The publication dates of the 165 primary study articles ranged from 1980 to 2009.

The MEDLINE®, Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, and the Health Technology Assessments database search for systematic reviews yielded 1746 citations. We identified 68 of these as potentially relevant and retrieved the full-text articles for further evaluation. Of these, 46 did not meet eligibility criteria. After examining the 22 qualifying systematic reviews, 11 were re excluded for various reasons (Appendix D; Figure 5).

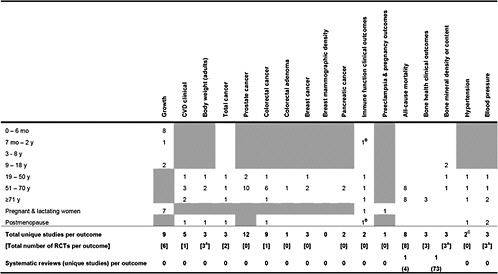

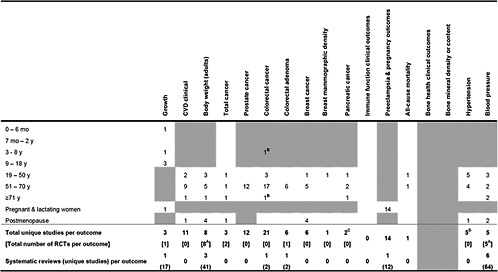

The grand overview tables (Tables 1, 2, and 3) detailed how many studies reported an outcome (either as a primary or secondary outcome) that is of interest and also listed the total number of unique studies (including those from systematic reviews) as each study may have provided data for more than one outcome.

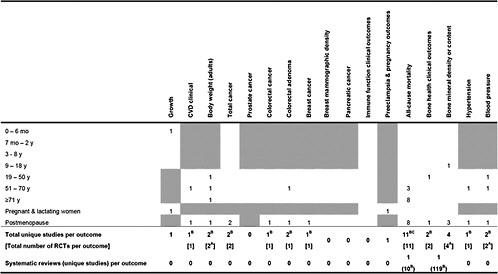

Table 1. Number of primary studies on Vitamin D intake or concentration and specific health outcomes that could be applicable to certain life stages

|

|

|

Shaded cells indicate that either the eligibility criteria excluded outcomes in those life stages or the outcomes are not applicable to those life stages. Blank unshaded cells indicate no primary studies were identified in this report in those life stages. A only RCTs were eligible for this outcome B Relationship between maternal 25(OH)D concentration and a topic eczema in infants C 1 study was a combined analysis of Nurses Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study |

Table 2. Number of primary studies on calcium intake and specific health outcomes that could be applicable to certain life stages

|

|

|

Shaded cells indicate that either the eligibility criteria exclued outcomes in those life stages of the outcomes are not applicable to those life stages. Blank unshaded cells indicate no primary studies were identified in this life stages. A Only RCTs were eligible for this outcome B Association between total calcium intake in childhood and colorectal cancer after 65 years of followup C 1 study was a combined analysis of Nurses Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study D 6 analyses, including 2 separate analyses of NHANES I |

Table 3. Number of primary studies on combined vitamin D and calcium intake and specific health outcomes that are relevant to certain life stages

|

|

|

Shaded cells indicate that either the eligibility criteria excluded outcomes in those life stages or the outcomes are not applicable to those life stages. Blank unshaded cells indicate no primary studies were identified in this report in those life stages. A Only RCTs were eligible for this outcome B Including the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial C A de novo reanalysis of the 10 RCTs in a previous systematic review and one newly added trial |

Vitamin D and health outcomes

Vitamin D and growth

We reviewed primary studies that evaluated relationships between vitamin D and growth parameters in infants and children.

Synopsis

Seven intervention studies and two observational studies evaluated intake or exposure to vitamin D and growth parameters in infants and children. Two intervention studies from the same center found a significant association of maternal vitamin D intakes with infant birth weights. Study methodologies were incompletely reported in these two studies. The rest of the studies did not find a significant association between either maternal or offspring vitamin D intake and offspring’s weight or height. No overall conclusions could be drawn as the studies reviewed had diverse populations and methodological approaches.

Detailed presentation (Tables 4, 5, 6 & 7)

Six RCTs34-40 and one nonrandomized comparative study41 in eight publications reported on the effect of vitamin D supplementation on growth parameters in infants and children. Two cohort studies reported on the association between maternal serum 25(OH)D concentration and her offspring’s growth parameters.42,43 The number of subjects in the RCTs ranged from 19 to 200. The two cohort studies had 374 and 466 subjects, respectively. The latitudes of the studies ranged from 38º to 51º. Four studies administered vitamin D exclusively to expectant mothers during the third trimester of pregnancy. One study administered vitamin D to both the lactating mothers and her offspring. Two studies administered vitamin D only to the infants or children. Followup ranged from delivery until 9 years. Methodological quality of two studies were rated B and seven studies were rated C. T he studies were limited by such factors as incomplete reporting and small sample sizes.

Infant 0 - 6 months; 7 months - 2 years; pregnant or lactating women

One RCT from UK administered vitamin D 1000 IU/d or placebo to 126 expectant mothers (first generation Asian immigrants) during the third trimester and found no significant difference between the infants’ birth weights or birth lengths and those of the control population.34,38 There were twice as many low birth weight infants (<2500 g) in the control group compared to the supplemented group (21.7% vs. 11.9%); however, this difference was not significant. A study from US supplemented 10 lactating mothers with vitamin D 400 IU/d and their infants with 300 IU/d for 6 months. Compared to the group where nine mothers received 6400 IU/d and their infants none, there was no significant difference in the infants’ weight or length at 1 month, 4 months, and 7 months of age.39 A study from China randomly assigned 255 newborn infants to 100, 200, or 400 IU/d of vitamin D for 6 months and reported no significant difference in weight or length among the three groups at 6 months of age.36 One study from India randomly selected 100 expectant mothers to receive a total of 1.2 million IU of vitamin D (600,000 IU of vitamin D2 in 7th and 8th month) during the third trimester. The newborns’ birth weight was significantly increased compared to those from 100 unsupplemented expectant mothers (difference 190 g).37 Important elements of the study methodology like randomization technique and any blinding of outcome assessors were not reported. An earlier nonrandomized comparison from the same study center involving smaller samples reported similar findings.41 The estimated baseline mean

dietary vitamin D intake in the expectant mothers from these two studies was less than 30 to 35 IU/d (the validity of these measures is unclear). An RCT from France supplemented 48 expectant mothers with either vitamin D 1000 IU/d in the third trimester or 200,000 IU one time dose at 7 month pregnancy and found no significant difference in the infants’ birth weights between the two methods.40 A cohort study from Australia analyzed the maternal serum 25(OH)D concentration in 374 women at 28-32 week gestation (geometric mean in winter 48 nmol/L; summer 69 nmol/L) and found no association with infant birth weight or length.43 One cohort study from UK analyzed the serum 25(OH)D concentration in 466 white women in late pregnancy (~33 wk) and found the concentrations (from <30 to >75 nmol/L) were not related to their offspring’s weight or height at birth, 9 months, and 9 years.42

9 - 18 years

One RCT of vitamin D3 (placebo, 200, or 2000 IU/d for 1 year) on girls in Lebanon aged 10-17 years found no significant difference at 1 year followup in weight or height among the 34 girls who were premenarchal at time of enrollment.35

Findings by life stage

-

0 – 6 mo One RCT found that supplementing expectant mothers with vitamin D 1000 IU/d during the 3rd trimester has no effect on infant birth weight or length. Another RCT found that supplementing expectant mothers with a total of 1.2 million IU of vitamin D during the 3rd trimester effected a significant increase in birth weight (+190 g). Background diet is low in vitamin D in this study. A studycompared supplementing lactating mothers with vitamin D 400 IU/d and their infants 300 IU/d for 6 months with mothers supplemented with 6400 IU/d and their infants none, there was no significant difference in the infants’ weight or length at 1 month, 4 months, and 7 months of age. Another study compared supplementing newborn infants with 100, 200, or 400 IU/d of vitamin D for 6 months and reported no significant difference in weight or length at 6 months of age. An RCT supplemented expectant mothers with either vitamin D 1000 IU/d during the third trimester or 200,000 IU one time dose at 7 month pregnancy and found no significant difference in the infants’ birth weights between the two methods. A cohort study analyzed the maternal serum 25(OH)D concentration at 28-32 week gestation (geometric mean in winter 48 nmol/L; summer 69 nmol/L) and found no association with infant birth weight or length. Another cohort study found that serum 25(OH)D concentration (ranged from <30 to >75 nmol/L) in late pregnancy (~33 wk) was not related to the newborn’s weight or height at birth, 9 months, and 9 years.

-

7 mo – 2 y A cohort study found that serum 25(OH)D concentration (ranged from <30 to >75 nmol/L) in late pregnancy (~33 wk) was not related to the newborn’s weight or height at birth, 9 months, and 9 years.

-

3 – 8 y No study covered this life stage.

-

9 – 18 y A cohort study found that serum 25(OH)D concentration (ranged from <30 to >75 nmol/L) in late pregnancy (~33 wk) was not related to the newborn’s weight or height at birth, 9 months, and 9 years. One RCT of vitamin D3 (placebo, 200, or 2000 IU/d for 1 year) on girls 10-17 years old found no significant difference at 1 year followup in weight or height among the girls who were premenarchal at time of enrollment.

-

19 – 50 y Not reviewed

-

51 – 70 y Not reviewed

-

≥71 y Not reviewed

-

Postmenopause Not reviewed

-

Pregnant & lactating women One RCT found that supplementing expectant mothers with vitamin D 1000 IU/d during the 3rd trimester has no effect on infant birth weight or length. Another RCT found that supplementing expectant mothers with a total of 1.2 million IU of vitamin D during the 3rd trimester effected a significant increase in birth weight (+190 g). Background diet is low in vitamin D in this study. A study compared supplementing lactating mothers with vitamin D 400 IU/d and their infants 300 IU/d for 6 months with mothers supplemented with 6400 IU/d and their infants none, there was no significant difference in the infants’ weight or length at 1 month, 4 months, and 7 months of age. An RCT supplemented expectant mothers with either vitamin D 1000 IU/d during the third trimester or 200,000 IU one time dose at 7 month pregnancy and found no significant difference in the infants’ birth weights between the two methods.

Table 4. Vitamin D on growth outcome: Characteristics of interventional studies

|

Author Year Study Name Location (Latitude) [PMID] |

Population |

Background Calcium Intake & Vitamin D Data |

Comparisons |

Compliance |

Comments |

|

|

RCTs |

||||||

|

Maxwell 198138 Brooke 198034 UK (51ºN) [6793058] [6989438] |

• Health status |

pregnancy |

25(OH)D at 28-32 wk: 20.1 nmol/L |

Vit D 1000 IU/d 3rd trimester only |

nd |

First generation Asian immigrants only |

|

• Mean age (range/SD), y |

nd |

|

||||

|

• Male (%) |

0 |

|||||

|

Feliciano 199436 China (22ºN to 47ºN) [8078115] |

• Health status |

healthy term |

86% infant breastfed until 5-6 mo |

Vit D 100 IU/d vs. 200 IU/d vs. 400 IU/d |

nd |

|

|

• Mean age (range/SD), y |

newborn |

|

|

|||

|

• Male (%) |

nd |

|

|

|

||

|

El-Hajj 200635 Lebanon (33ºN) [16278262] |

• Health status |

healthy |

25(OH)D 35 nmol/L; dietary Ca 677 mg/d |

Vit D3200 IU/d vs. 2000 IU/d vs. placebo × 1 y |

98% in placebo; 98% in low dose; 97% in high dose |

7.4 h sun exposure/wk |

|

• Mean age (range/SD), y |

13.2 (10-17) |

|

|

|||

|

• Male (%) |

0 |

|

|

|||

|

Wagner 200639 Charleston, US (32ºN) [17661565] |

• Health status |

Fully lactating; <1 mo postpartum |

Lactating mother’s dietary vit D 273 IU/d; dietary calcium intake: 1125 mg/d; |

Mother Vit D3 400 IU/d + infant 300 IU/d vs. mother 6400 IU/d + infant 0 IU/d |

80% in mothers; as low as 61% for infants |

78% white; 11% black; 11% Hispanic |

|

• Mean age (range/SD), y |

29 |

|

||||

|

• Male (%) |

0 |

|

|

|||

|

Marya 198837 India (28ºN) [3243609] |

• Health status |

no pregnancy-related complications |

Expectant mother’s dietary Vit D 35 IU/d; calcium 429 mg/d |

Mother Vit D 1.2 mil IU (total; 600,000 IU vit D2 in 7th & 8th mo) vs. no supplement |

nd |

|

|

• Mean age (range/SD), y |

24 |

|

|

|||

|

• Male (%) |

0 |

|

|

|||

|

Mallet 198640 France (48º N) [3755517] |

• Health status |

pregnancy |

Ca intake 550 to 1000 mg/d in 55% of the subjects |

Vit D 1000 IU/d vs. 200,000 IU 1× dose |

nd |

|

|

• Mean age (range/SD), y |

newborn |

|

||||

|

• Male (%) |

nd |

|

|

|

||

|

Nonrandomized comparative study |

||||||

|

Marya 198141 India (28ºN) [7239350] |

• Health status |

no pregnancy-related complications |

Expectant mother’s daily milk intake <500 mL; dietary Vit D <30 IU/d |

Vit D 1200 IU/d + Ca 375 mg/d (3rd trimester) or Vit D 1.2 mil IU (total; 600,000 IU in 7th & 8th mo) or no supplement |

nd |

|

|

• Mean age (range/SD), y |

nd |

|

||||

|

• Male (%) |

0 |

|

|

|||

Table 5. Vitamin D and growth outcomes: Characteristics of cohort studies

|

Author Year Study Name Location (Latitude) [PMID] |

Population |

Vitamin D Concentration |

Comparisons |

Confounders/Effect Modifiers Adjusted |

Comments |

|||||||

|

Nutrients |

Demograph |

Anthrop |

Medical |

UV exposure |

Lifestyle |

|||||||

|

Morley 200643 Australia (38ºS) [16352684] |

• Health status |

singleton pregnancy; no disease |

• Assay method |

RIA |

Length and weight in offspring stratified by mother’s 25(OH)D |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

99% white; excluded dark skin or women with concealing clothing |

|

• Mean age (range/SD), y |

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

• Male (%) |

0 |

• Season blood drawn |

winter & summer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gale 200842 PAHSG UK (50ºN) [17311057] |

• Health status |

singleton pregnancy <17 wk |

• Assay method |

RIA |

Length and weight in offspring stratified by mother’s 25(OH)D |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

White only |

|

• Mean age (range/SD), y |

26.3 |

|||||||||||

|

|

• Male (%) |

0 |

• Season blood drawn |

nd |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 6. Vitamin D and growth outcomes: Results of RCTs

|

Author Year Study Name [PMID] |

Life Stage |

Outcome |

1°/2° |

Mean Followup |

Interventions, Daily Dose |

No. Analyzed |

Unit |

Baseline |

Change (SD) |

Change 95% CI |

Net Diff |

Net Diff 95% CI |

P Btw |

Study Quality |

|

Maxwell 198138 Brooke 198034 [6793058] [6989438] |

Pregnant women & infant 0-6 mo (Asians) |

Infant birth weight |

2° |

until delivery |

Vit D 1000 IU |

59 |

g |

NA |

Final 3157 |

3037, 3277 |

Diff +123 |

−50, 296C |

NS |

B |

|

|

|

Control |

67 |

|

NA |

3034 |

2909, 3159 |

|

|

|

||||

|

Infant birth length |

2° |

until delivery |

Vit D 1000 IU |

59 |

cm |

NA |

Final 49.7 |

49.6, 49.8 |

Diff +0.2 |

0.1, 0.3C |

NS |

|||

|

|

|

|

Control |

67 |

|

NA |

49.5 |

49.4, 49.6 |

|

|

|

|||

|

Feliciano 199436 [8078115] |

0-6 mo |

Weight gain born in spring, N. ChinaA |

1° |

6 mo |

Vit D 400 IU |

12 |

g |

nd |

3745 |

2613, 4877 |

−463 |

926C |

NS |

C |

|

|

|

|

Vit D 200 IU |

13 |

|

nd |

5296 |

4718, 5874 |

1088 |

96, 2080C |

NS |

|||

|

|

|

|

Vit D 100 IU |

17 |

|

nd |

4208 |

3402, 5013 |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Length gain born in spring, N. China |

1° |

6 mo |

Vit D 400 IU |

12 |

cm |

nd |

18.8 |

17.4, 20.2 |

−0.5 |

−2.7, 1.7C |

NS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vit D 200 IU |

13 |

|

nd |

19.0 |

18.1, 19.9 |

−0.3 |

−2.2, 1.6C |

NS |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Vit D 100 IU |

15 |

|

nd |

19.3 |

17.6, 21.0 |

|

|

|

||

|

El-Hajj 200635 [16278262] |

9-18 y female, premenarche |

Height |

2° |

1 y |

Vit D3 2000 IU |

nd, ≤34 total |

% |

nd |

5.6% |

|

~1.8% |

~0.6, 3.0 |

0.07 |

C |

|

|

|

Vit D3 200 IU |

|

nd |

5.0% |

|

~1.2% |

−0.01, 2.4C |

|

|||||

|

|

|

Placebo |

|

nd |

3.8% |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Weight |

2° |

1 y |

Vit D3 2000 IU |

nd, ≤34 total |

% |

nd |

18.4% |

|

~3.5% |

~-1.3, 8.3C |

0.25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vit D3 200 IU |

|

nd |

15.3% |

|

~0.4 |

−3.7, 4.5C |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Placebo |

|

nd |

14.9% |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Wagner 200639 [17661565] |

Lactating mothers & infant 0 - 6 mo; 7 mo - 2 y |

Infant weightB |

1° |

7 mo |

Mother (400) |

10 |

g |

NA |

Final 7600 |

7100, 8100 |

Diff -800 |

−2300, 700C |

0.30 |

C |

|

|

|

+infant (300) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Mother (6400) |

9 |

|

NA |

8400 |

7700, 9100 |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

+infant (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

Infant length |

1° |

7 mo |

Mother (400) |

10 |

cm |

NA |

Final 65.5 |

64.4, 66.6 |

Diff −3.8 |

−7.8, 0.2C |

0.06 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

+infant (300) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Mother (6400) |

9 |

|

NA |

69.3 |

67.4, 71.2 |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

+infant (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Marya 198837 India [3243609] |

Pregnant women & infant 0-6 mo |

Birth weight |

1º |

Delivery |

Vit D 1.2 mil |

100 |

g |

NA |

Final 2990 |

2920, 3060 |

Diff +190 |

90, 290C |

<0.001 |

C |

|

|

|

IU total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

No supplement |

100 |

|

NA |

2800 |

2730, 2870 |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Birth length |

2º |

|

Vit D 1.2 mil |

100 |

cm |

NA |

Final 50.06 |

49.7, 50.4 |

Diff +1.6 |

1.1, 2.1C |

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

IU total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

No supplement |

100 |

|

NA |

48.45 |

48.1, 48.8 |

|

|

|

||

|

Marya 198141 [7239350]E |

Pregnant women & infant 0-6 mo |

Birth weight |

2º |

Delivery |

Vit D 1.2 mil |

20 |

g |

NA |

Final 3140 |

2940, 3340 |

Diff +410 |

166, 654C |

0.001 |

C |

|

|

|

IU total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Vit D 1200 IU |

25 |

g |

NA |

Final 2890 |

2760, 3020 |

Diff +160 |

0, 320C |

0.05 |

||||

|

|

|

|

+ 375 mg Ca (3rd trimester) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

No supplement |

75 |

|

NA |

2730 |

2650, 2810 |

|

|

|

|

Author Year Study Name [PMID] |

Life Stage |

Outcome |

1°/2° |

Mean Followup |

Interventions, Daily Dose |

No. Analyzed |

Unit |

Baseline |

Change (SD) |

Change 95% CI |

Net Diff |

Net Diff 95% Cl |

P Btw |

Study Quality |

|

Mallet40 1986 France (48º N) [3755517] |

Pregnant women & infant 0-6 mo |

Birth weight |

2° |

delivery |

Vit D 1000 IU |

21D |

g |

NA |

Final 3370 (80) |

|

Diff +160 |

|

NS |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

Vit D 200,000 IU 1× dose |

27D |

|

NA |

3210 (90) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A See Table 1 in original paper for complete results stratified by North vs. South China and birth in spring vs. fall B See Table 3 in original paper for results on 1 mo and 4 mo C Estimated from available data D Estimated from number of mothers; number of infants not reported E This is not an RCT; the supplemented groups were randomized, but not the control (non-supplemented group); data from comparisons between the supplemented groups not reported. |

||||||||||||||

Table 7. Vitamin D and growth outcomes: Results of cohort studies

|

Author Year Study Name PMID |

Life Stage |

Outcome (n/N; Incidence) |

Followup Duration |

Maternal 25(OH)D concentration, nmol/L |

No. in Category |

Final value |

Final SD |

P value |

Study Quality |

|

Morley 200643 Australia [16352684] |

Pregnant women; infant 0-6 mo |

Birth weight (N=374) |

Delivery |

<28 at 28-32 wk |

27 |

3397 g |

57 |

NS |

B |

|

|

|

≥28 at 28-32 wk |

347 |

3555 |

52 |

|

|||

|

|

Birth length (N=374) |

Delivery |

<28 at 28-32 wk |

27 |

49.8 cm |

2.7 |

NS |

||

|

|

|

|

|

≥28 at 28-32 wk |

347 |

50.4 |

2.4 |

|

|

|

Gale 200842 PAHSG, UK [17311057] |

Pregnant women; infant 0-6 mo |

Birth weight (N=466) |

Delivery |

<30 (Quartile) |

nd |

3.38 kg |

0.46 |

0.25A |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

30-50 |

nd |

3.40 |

0.56 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

50-75 |

nd |

3.49 |

1.57 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

>75 |

nd |

3.43 |

0.51 |

||

|

|

|

Weight at 9 mo (N=440) |

9 mo |

<30 |

nd |

15.9 |

1.14 |

0.58 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30-50 |

nd |

15.8 |

1.26 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

50-75 |

nd |

16.1 |

1.34 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

>75 |

nd |

15.9 |

1.09 |

||

|

|

|

Weight at 9 y (N=178) |

9 y |

<30 |

nd |

27.4 kg |

1.19 |

0.10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30-50 |

nd |

29.4 |

1.21 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

50-75 |

nd |

30 |

1.20 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

>75 |

nd |

29.3 |

1.19 |

||

|

|

Pregnant women; infant 0-6 mo |

Birth length (N=466) |

Delivery |

<30 |

nd |

50 cm |

1.83 |

0.15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30-50 |

nd |

50 |

2.29 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

50-75 |

nd |

50.5 |

2.25 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

>75 |

nd |

50.1 |

2.09 |

||

|

|

|

Length at 9 mo (N=440) |

9 mo |

<30 |

nd |

71.2 cm |

2.85 |

0.86 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30-50 |

nd |

71.4 |

2.60 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

50-75 |

nd |

71.7 |

2.89 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

>75 |

nd |

71.1 |

2.67 |

||

|

|

|

Height at 9 y (N=178) |

9 y |

<30 |

nd |

129.6 cm |

5.88 |

0.19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30-50 |

nd |

131.5 |

6.66 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

50-75 |

nd |

131.8 |

5.09 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

>75 |

nd |

130.6 |

6.45 |

||

|

ANon-adjusted |

|||||||||

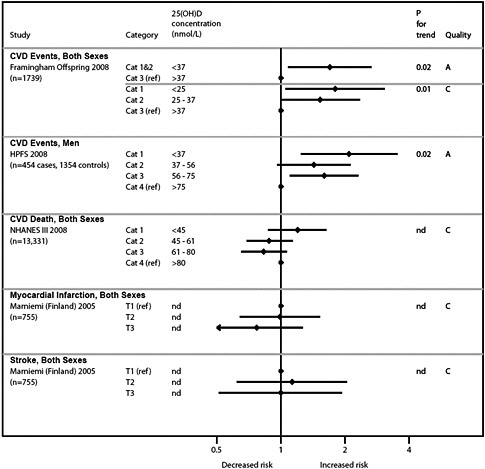

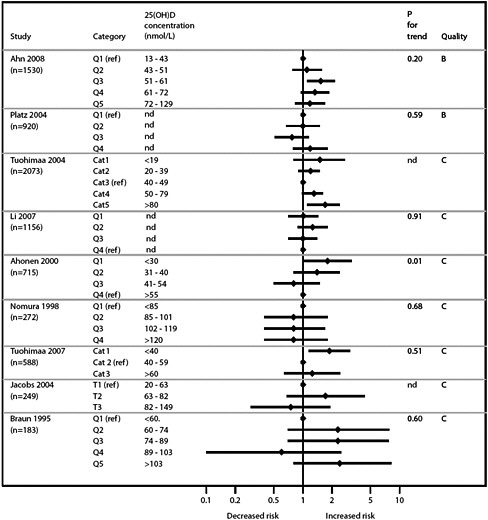

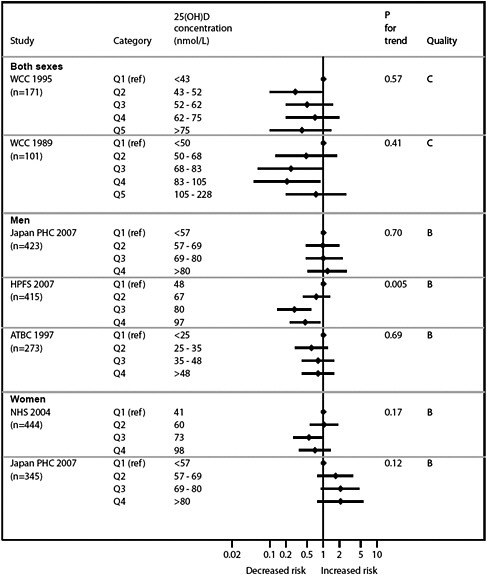

Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease

Synopsis