D

Health Literacy and the Health Reform: Where Do Children Fit In?

Lee M. Sanders, M.D., M.P.H. Comments for Institute of Medicine Workshop on Health Literacy and Health Reform November 10, 2010

LIFE-COURSE PERSPECTIVE ON HEALTH LITERACY

At least 1 in 3 parents of young children have limited health literacy skills. Limited health literacy is independently associated with each of the major child-health objectives in Healthy People 2010. Two recent reviews suggest that the strongest and most consistent associations are those between a mother’s health literacy and her own mental health (itself a modifiable determinant of child health), between a mother’s health literacy and her child’s access to needed care, and between an adolescent’s health literacy and her/his likelihood to engage in risky health behaviors.

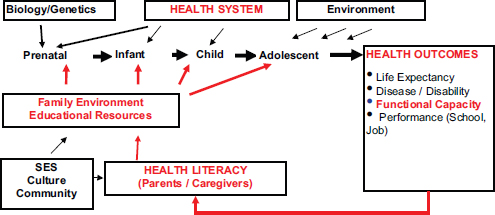

The Affordable Care Act provides several opportunities for state and federal agencies, alongside health plans and community-based organizations, to address these literacy-related disparities in child health, but doing so will require a life-course perspective that reaches from infancy through old age. (See Figure D-1.) At the individual level, imagine the following scenario: Ms. Garcia is a second-generation, legal immigrant from Central America; she has limited English proficiency, less than a 7th-grade education, works as a hotel janitor, and has just given birth to her first child, Zoe. During infancy and early childhood, the educational system provides Zoe access to a high-quality preschool (building Zoe’s emergent-literacy skills) and her mother access to adult basic education (building Ms. Garcia’s job prospects), and the health system provides Zoe with comprehensive and continuous health insurance (allowing access to needed preventive and acute care), an intensive nurse home visiting program (building Ms. Garcia’s health literacy skills), and a family-centered

FIGURE D-1 Life course perspective on health literacy.

SOURCE: Sanders, L.M., adapted from Halfon, N., Hochstein, M. Milbank Quarterly 2002; 80(3):433.

medical home (embracing needed medical, dental, nutritional, and psychosocial support services). During the school-age years and adolescence, the educational system provides Zoe an effective curriculum that integrates developmentally appropriate health-behavior content within her reading, math and science curricula, and the health system continues to provide access to the family-centered medical home. As a health-literate adult, Zoe effectively accesses and uses written and electronic health information, and she serves as an effective advocate for her own health, for her children’s health, and for her grandchildren’s health.

At the population-health and public-policy level, this life-course perspective suggests that improving the nation’s health will require coordinated investments from educational and health systems to support the health literacy skills of individuals as they mature from newborn citizens to senior citizens.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In response to the Affordable Care Act, the Institute of Medicine’s Health Literacy Roundtable could best improve the ACA’s attention to this life-course perspective on child health by focusing discussions on community-based funding, advocacy, and research on the following priorities:

- To Extend Coverage to All Children: Simplify the CHIP and Medicaid Enrollment Process.

- To Improve the Quality of Child Health Care: Target and Tailor Medical-Home Services for Low-Literacy Parents of Children with Complex Chronic Illnesses.

- To Improve Child Medication Safety: Promote National Standards for Safe-Use Labeling of Pediatric Liquid Medication.

- To Improve the Skills of the Pediatric Workforce: Advocate for Effective Health Literacy Training as a Required Competency for Post-Graduate Training in Pediatrics.

1. EXTENDING HEALTH-INSURANCE COVERAGE TO ALL CHILDREN

Background. At least 9 million U.S. children are uninsured, and of those, at least 5 million are eligible for public insurance, including Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Rates of uninsured children are highest in under-resourced communities with the highest prevalence of low-literacy and limited English-proficiency adults. Adjusting for income, age, and English-language proficiency, a recent analysis of the NAAL indicates that children of caregivers with low health literacy are significantly more likely to be uninsured.14 These children are also more likely to have unmet health care needs,26 to make more unnecessary visits to the emergency room,27 and to be enrolled in other eligible social programs (e.g., WIC, TANF). (Pati S, et al. Influence of Maternal Health Literacy on Child Participation in Social Welfare Programs: The Philadelphia Experience. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1662-1665.)

Many parents are unable to understand and complete child-health-insurance enrollment documents, and for state programs like Medicaid and CHIP, many more are impeded by the cumbersome enrollment process. On a single item from the National Assessment of Adult Literacy, nearly 2 in 3 were not able to fill in the name and birth date in the appropriate places on a health-insurance form. In 2007, 26 states used enrollment forms for CHIP too complex for most U.S. adults to understand. Their written instructions were written above the 10th-grade level, and the forms themselves were assessed as too difficult to complete by independent standards (“Suitability Assessment of Materials”) and CHIP-legislated standards.19 While the complexity of enrollment forms is clearly a significant enrollment barrier for low-literacy families with CHIP or Medicaid-eligible children,97 a recent Urban Institute study suggested that the barriers to CHIP enrollment were myriad, including cumbersome enrollment eligibility screening processes, narrow enrollment periods, and under-resourced state outreach efforts. In response to Children’s Health Insurance Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA) incentives—only 17 states have implemented “eligibility simplification efforts” (e.g., continuous eligi-

bility, elimination of the face-to-face interview, presumptive eligibility for newborns born to Medicaid-insured mothers, and use of a bundled eligibility for multiple programs). To date, these efforts have resulted in enrolling at least 1 million children in CHIP or Medicaid.

ACA-Related Recommendations. ACA and CHIPRA provide ample opportunity to expand insurance coverage for all children in the United States. Bridging literacy-related barriers is made possible by three ACA provisions (Sec. 1413, 2715, and 3306), which complement the CHIPRA incentives for simplifying the enrollment process. ACA and CHIPRA afford all states the funding to do the following:

A. Conduct low-literacy CHIP-enrollment outreach campaigns, targeting communities with the highest prevalence of low literacy skills among adult caregivers of young children. Community-based organizations are essential to the success of these campaigns, and they should have easy access to national resources, such as ARHQ’s Health Literacy Toolkit, to help reach and communicate with low-literacy communities. Easy-to-understand, single-page explanations of ACA should be developed. (See Box D-1 for draft language.)

B. Assure that paper and web-based application forms for CHIP and Medicaid are written at or below established suitability and grade-level standards. In accordance with the Plain Language Act, specific deadlines, designated officials at state and federal levels, and reporting provisions may be issued by HHS to assure that these standards are met.

C. Bundle the eligibility assessment for all maternal and child health programs (e.g., WIC, SNAP, school-lunch program, CHIP, Medicaid for children, and Medicaid for adult caregivers of eligible children). Disseminated established state-based best practices (developed in the early months of CHIPRA simplification efforts), Centers for Medicaid and Medicare (CMS) could provide models for such bundled eligibility and enrollment processes to all states. CMS and their state-based counterparts could encourage interagency agreements to facilitate “presumptive eligibility” across health, nutritional, and social-service programs.

D. Assess eligibility for all maternal and child-health programs at school entry and at school health clinics. Public-school enrollment and orientation, as well as enrollment activities for Head Start and other federally-subsidized child-care centers, should be designated as “priority portals” for the Health Insurance Exchanges established by the ACA. This may provide additional opportunity to guarantee insurance coverage, not just for school-aged children but also for their parents, grandparents and other adult caregivers.

BOX D-1

What the Health Reform Act Means for Your Child

- It makes sure that your child has health insurance.

- It makes sure that your child will get immunizations and regular health checks.

- It makes sure that your child has a regular place to go to get medical care.

If your child is over age 18, it allows your child to stay on your health insurance plan until age 26.

In some states and counties:

- If your child was just born, the Act may provide a specially trained nurse to visit your home. The nurse will help you get through those difficult first few weeks.

- If your child has a chronic medical or behavioral problem, a specialized nurse will help you manage the problem at home and at school.

More information at www.kidshealth.org

2. IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF HEALTH CARE FOR ALL CHILDREN

Background. Improving health care quality for all children will likely require health system changes that provide each child with a Family-Centered Medical Home, an evidence-based system of care that was originally developed to attend to the needs of children with complex chronic conditions.2,4,73 The key components of a family-centered medical home are continuous access to comprehensive, culturally effective, and coordinated care that meets the health and developmental needs of the child and her/ his family. In practice, this often means minor restructuring to a hospital or primary care system that facilitates 24/7 telephone access and a care coordinator (nurse, parent, or community health worker) to serve as a patient navigator. Nurse home-visiting programs, normally implemented in the first year after a child’s birth, help support the family-centered medical home by providing mothers with individualized, home-based education on infant care, increased access to maternal and child primary care services, and increased access to other social services (e.g., breastfeeding and nutritional support, maternal mental health services, and child developmental screening and intervention services). Children’s hospitals, academic medical systems, and pediatric managed-care organizations,

and have led large-scale, multisite demonstration projects demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of the family-centered medical home model.

The Family-Centered Medical Home has been most effective in improving health-care quality for children with special health care needs (CSHCN). Children with special health care needs (CSHCN) are defined as children with “a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.” CSHCN represent less than 15% of all U.S. children, and at least 20% of the children of parents in low-income, low-literacy communities. However, CSCHN are responsible for more than 70% of child health care expenditures.27,74 Compared with other children, CSHCN have 2.5 times the number of missed school days; experience twice as many unmet health needs; and account for 5 times as many hospital days.63 Common child chronic conditions include asthma, oral health problems, and behavioral health conditions (including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), but many CSHCN have rare congenital disorders and multiple comorbid conditions. Among the adults who care for CSHCN, more than 30% have low health literacy.

The children of low-literacy adults are at greatest risk for low health care quality, as measured by health care utilization, health behaviors, and other health outcomes. In studies among children with asthma and type-1 diabetes, those who have caregivers with low health literacy are at increased risk for unmet health care needs, worse control of illness, and more preventable use of the emergency room.92-95 Adjusted for socioeconomic status and ethnicity, mothers with low health literacy skills are more likely to smoke96 and to have depressive symptoms.45-48 Several studies have demonstrated that mothers with low literacy were significantly less likely to understand information regarding home safety for young children.15,29 Low maternal health literacy is associated with increased risk for child obesity—including a decreased likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding at two months postpartum,40 decreased ability to understand and use and WIC information,51 nonuse of nutrition-fact labels when choosing food for their children,42 and inaccurate perception of child weight.43

Parent health literacy may be a critical family-centered characteristic that moderates the effectiveness of the Family-Centered Medical Home—for children with chronic health conditions, for children at risk for chronic-health conditions, and for all children. At the level of state programs, health systems, and individual practices—a Family-Centered Medical Home reform offers ready opportunities to implement both “universal health literacy precautions” and targeted approaches that provide families with limited health literacy a more culturally effective and intensive care coordination to meet their children’s health needs.

ACA-Related Recommendations. ACA provides significant opportunities to implement literacy-sensitive approaches to the Family-Centered Medical Home:

- Tailor Quality Improvement Efforts for Low-Literacy Families in the Family-Centered Medical Home. By mandating attention to “consumer health literacy” in the actions of AHRQ’s newly established Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety, Section 3501 of ACA encourages all federally funded QI efforts to accommodate adults with limited literacy skills, including adults who care for young children. Accountable care organizations (ACOs) should provide child health care coordination that targets low-literacy communities. Public health and health care agencies may be able to use parent literacy skills, alongside other risk adjustment measures, to target enhanced care coordination services. With diminished resources and increased incentives to reduce costs—Medicaid managed care organizations and the new Accountable Care Organizations established by ACA may be able to improve the quality of care for children with complex conditions by tailoring their care-coordination services to match the health literacy skills of their parents. The result may be significant reductions in disparities for children with special health care needs.

- Develop Low-Literacy Decision Aids for the Family-Centered Medical Home. By funding the CDC and the NIH to develop low-literacy decision aids to enhance shared decision making, Section 3506 provides a platform for developing systems that increase parent and child involvement in the care of a child chronic illness. To be effective for child health, these decision aids must be family-centered, with an attention not only to the literacy-needs of parents, but also to the developmentally-appropriate literacy skills of children. One pressing need is to develop, test, and disseminate electronic child health records that are understandable and useful to all stakeholders: children, their parents, their care providers, and their care coordinators.

- Test the Cost-Effectiveness of Health Literacy Interventions, through Demonstration Projects for the Family-Centered Medical Home. In addition to $225 million in CHIPRA demonstration-project funding, ACA funds a new Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMI) that will fund quality-improvement demonstration programs in care coordination, as well as additional funds for maternal-infant home visiting programs (Sec. 2951) and childhood obesity demonstration projects (Sec. 4306). Each of these demonstration projects provides an opportunity to integrate and assess the cost-

effectiveness of literacy-sensitive approaches. In addition to the targeted approaches and tools described above, these may include literacy-sensitive tools (and accompanying training for health care and paraprofessional staff) that target high-impact child health outcomes: healthy nutritional and physical activity behaviors, child-safety behaviors, oral health practices, childhood immunizations, interpretation of common child health screening tests, parent mental health, and parent smoking cessation.

3. TO IMPROVE CHILD MEDICATION SAFETY

Medication errors may be more likely in families with limited literacy skills. Interpretation of dosing charts for OTC medicines is significantly more difficult for caregivers with limited literacy or numeracy skills.30-32,69 A recent study by Lokker et al demonstrated that at least two in three caregivers considered over-the-counter (OTC) cough and cold medications appropriate for infants, despite viewing package labeling that suggested otherwise; misinterpretation of OTC product age indication was highest among those with the lowest numeracy skills.33 Other work has demonstrated that multiple reasons for confusion and misdosing of common liquid pediatric medications. Using commonly distributed dosing cups, parents are prone to significant errors in dosing liquid prescription medication. In one study of a common pediatric prescription medication, Yin et al.30 documented a mean error rate of 48% from the recommended dose. Several investigators have demonstrated the effectiveness of more clearly labeled dosing devices, the use of pictograms, and other low-literacy tools in reducing parent dosing errors.

ACA-Related Recommendations. Section 3507 of the ACA provides specific mandate for the HHS to improve the safe use of medications by adopting and implementing new evidence-based standards for prescription medication labeling. With particular attention to the care of children who rely on liquid medication, the health literacy opportunities include the following:

- Adopt and enforce standards for dosing instructions for nonprescription pediatric liquid medication.

- Adopt and enforce standards for dosing instructions for prescription liquid medication.

- Adopt and enforce standards for the use of safe, easy-to-use dosing devices for liquid medication.

4. TO IMPROVE SKILLS OF THE PEDIATRIC WORKFORCE

Background. Medical providers’ ability to address health literacy related communication barriers undergird all of the 6 competencies developed by the American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). These competencies include interpersonal communication, professionalism, practice-based learning, systems-based practice, patient care, and medical knowledge. Nonetheless, the ACGME and the professional bodies that regulate post-graduate training for physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners have no specific requirement to train these providers in evidence-based communication skills.

Among pediatric providers who have completed their post-graduate training, there is a widely recognized sense of incompetency and need for greater training to meet the literacy and language demands of their patients and families. In a recent survey of a nationally representative sample of pediatric providers, more than 75% reported no regular use of evidence-based communication skills—such as employing teach-back conversations, reducing medical jargon, and using drawings or low-literacy texts to enhance verbal communication. Happily, nearly 2 in 3 providers suggested they would be interested in training to help address these deficiencies.

In 2009, the American Academy of Pediatrics launched an interactive, online training module in Health Literacy as part of its PediaLink™ training center. Its brief, actionable pages comply with educational and behavioral theory, and it has been effectively pretested among pediatric trainees. Use of the module nationwide, however, remains minimal. Other similar, evidence-based training modules for internal-medicine physicians and for more general populations of medical providers are also available.

ACA-Related Recommendations. By Amending Title VII of the Public Health Service Act, Section 5301 of the ACA provides HHS the opportunity, mandate, and funding to equip the future physician workforce to address modifiable causes of disparities (especially language and literacy). To realize this goal, the IOM Roundtable on Health Literacy should join HHS, HRSA, and other federal agencies to partner with professional organizations responsible for medical-provider training. Specifically for pediatrics, these include the ACGME, the AAP, the Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD), and the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP). These agencies and societies should agree to the following:

- Make health literacy training a required component of postgraduate training in child health (e.g., Pediatrics, Family Medicine, Pediatric Nurse Practitioners)

- Improve and disseminate evidence-based Health Literacy Training Modules for pediatric providers, trainees, and community providers alike.

Acknowledgment: Thanks to Kartik Telekuntla for his assistance with background research and checking references.

INFORMATION SOURCES

1. U.S. Preventive Services Taskforce, www.thecommunityguide.gov, accessed October 20, 2008.

2. AAP National Center of Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs, www.medicalhomeinfo.org, accessed March 8, 2009.

3. Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan P. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Third Edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008.

4. Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care. 2002;40:395-404.

5. Bennett CL, Ferreira MR, Davis TC, et al. Relation between literacy, race, and stage of presentation among low-income patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16: 3101-4.

6. Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288:475-82.

7. Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, et al. Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(5):391-8.

8. Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, Nurss JR. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease. A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:166-72.

9. Battersby C, Hartley K, Fletcher AE, et al. Cognitive function in hypertension: a community based study. J Hum Hypertens. 1993;7:117-23.

10. Arnold CL, Davis TC, Berkel HJ, et al. Smoking status, reading level, and knowledge of tobacco effects among low-income pregnant women. Prev Med. 2001;32:313-20.

11. Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction. In National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Selden CR, Zorn M, et al., Ed. NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

12. Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer A, Kindig DA. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004.

13. National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. A First Look at the Literacy of America’s Adults in the 21st Century. NCES Publication No. 2006-470.

14. Kutner, M, Greenberg, E, Jin,Y, et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006.

15. Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, et al. The Health Literacy of Parents in the U.S.: A Nationally Representative Study. Submitted to Pediatrics (contained in this supplement).

16. Davis TC, Humiston SG, Arnold CL, et al. Recommendations for effective newborn screening communication: results of focus groups with parents, providers, and experts. Pediatrics. 2006;117:S326-40.

17. Arnold CL, Davis TC, Frempong JO, et al. Assessment of newborn screening parent education materials. Pediatrics 2006;117(5 Pt 2):S320-5.

18. Farrell M, Deuster L, Donovan J, Christopher S. Jargon during counseling about newborn screening. Pediatrics 2008;122:243-50.

19. Sanders L, Federico S, Abrams MA, et al. Readability of enrollment forms for the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting, Toronto, Canada, Platform Presentation, 5-8 May 2007.

20. Davis TC, Mayeaux EJ, Fredrickson D, et al. Reading ability of parents compared with reading level of pediatric patient education materials. Pediatrics. 1994;93:460-68.

21. Davis TC, Crouch MA, Wills G, et al. The gap between patient reading comprehension and the readability of patient education materials. J Fam Pract. 1990;31:533-38.

22. CDS VIS for Polio, accessed May 26, 2007, at http://www.cdc.gov/nip/publications/vis/vis-IPV.txt.

23. Forbes SG, Align A. Poor readability of written asthma management plans found in national guidelines. Pediatrics. 2002;109(4):e52.

24. Abrams MA, Dreyer BP, Eds. Plain Language Pediatrics: Health Literacy Strategies and Communication Resources for Common Pediatric Topics. American Academy of Pediatrics: Elk Grove Village, IL; 2009.

25. D’Allesandro DM, Kingsley P, Johnson-West K. The readability of pediatric patient education materials on the world wide web. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 2001;155:807-12.

26. Sanders LM, Lewis J, Brosco JP. Low caregiver health literacy: risk factor for child access to a medical home. Presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting; May 15, 2005; Washington, DC.

27. Sanders LM, Thompson VT, Wilkinson JD. Caregiver health literacy and the use of child health services. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):86-92.

28. Fredrickson DD, Washington RL, Pham N, et al. Reading grade levels and health behaviors of parents at child clinics. Kans Med. 1995;96:127-9.

29. Llewellyn G, McConnell D, Honey A, et al. Promoting health and home safety for children of parents with intellectual disability: a randomized controlled trial. Res Dev Disabil. 2003;24:405-31.

30. Yin HS, Dreyer BP, Foltin G, et al. Association of low caregiver health literacy with reported use of nonstandardized dosing instruments and lack of knowledge of weight-based dosing. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(4):292-8.

31. Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank W, et al. To err is human: patient misinterpretations of prescription drug label instructions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):293-300.

32. Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12)887-94.

33. Lokker N, Sanders LM, et al. Misinterpretation of over-the-counter cough and cold medications. Pediatrics. In press 2008.

34. Davis TC, Byrd RS, Arnold CL, et al. Low literacy and violence among adolescents in a summer sports program. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24:403-11.

35. Stanton WR, Feehan M, McGee R, Silva PA. The relative value of reading ability and IQ as predictors of teacher-reported behavior problems. J Learn Disabil. 1990;23:514-7.

36. McGee R, Prior M, William S, et al. The long-term significance of teacher-rated hyperactivity and reading ability in childhood: findings from two longitudinal studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43(8):1004-17.

37. Miles SB, Stipek D. Contemporaneous and longitudinal associations between social behavior and literacy achievement in a sample of low-income elementary school children. Child Development. 2006;77(1);103-17.

38. Hawthorne G. Pre-teenage drug use in Australia: the key predictors and school-based drug education. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20:384-95.

39. Fortenberry JD, McFarlane MM, Hennessy M, et al. Relation of health literacy to gonorrhea related care. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:206-11.

40. Kaufman H, Skipper B, Small L, et al. Effect of literacy on breast-feeding outcomes. South Med J. 2001;94:293-6.

41. Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, et al. Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:391-8.

42. Kyvelos E, Mendelsohn AL, Tomopoulos S, et al. Use of Food Labels by Low Socioeconomic Status (SES) Parents: Associations with Material Hardship and Health Literacy. Pediatric Academic Societies’Meeting. May 2008, Honolulu, HI E-PAS2008:635811.10.

43. Yin HS, Dreyer BP, van Schaick L, et al. Factors associated with overweight status in low SES children: role of parent health literacy. Pediatric Academic Societies’Meeting. May 2008, Honolulu, HI. E-PAS2008:634474.49.

44. Arnold CL, Davis TC, Berkel HJ, Jet al. Smoking status, reading level, and knowledge of tobacco effects among low-income pregnant women. Prev Med. 2001;32:313-20.

45. Weiss BD, Francis L, Senf JH, et al. Literacy education as treatment for depression in patients with limited literacy and depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):823-8.

46. Bennett I, Switzer J, Aguirre A, et al. “Breaking it down”: patient-clinician communication and prenatal care among African American women of low and higher literacy. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(4):334-40.

47. Sanders LM, Shone LP, Conn KM, et al. Parent depression and low health literacy: risk factors for child health disparities? Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting, Toronto, Canada, 5-8 May 2007.

48. Poresky RH, Daniels AM. Two-year comparison of income, education, and depression among parents participating in regular Head Start or supplementary Family Service Center Services. Psychol Rep. 2001;88:787-96.

49. Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977.

50. Berwick D. Eleven worthy aims for clinical leadership of health system reform. JAMA. 1994;272(10):797-805.

51. Newes-Adeyi G, Helitzer DL, Roter D, Caulfield LE. Improving client-provider communication: evaluation of a training program for women, infants and children (WIC) professionals in New York state. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55(2):210-7.

52. Williams MV, Davis TC, Parker RM, Weiss BD. The role of health literacy in patient-physician communication. Fam Med. 2002;34:383-89.

53. Whitlock ER, Qrleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:267-84.

54. Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. BMJ 1999; 319(7212):766-71.

55. Flowers L. Teach-back improves informed consent. OR Manager. 2006;22(3):25-6.

56. Mayeaux EJ Jr, Murphy PW, Arnold C, et al. Improving patient education for patients with low literacy skills. Am Fam Physician. 1996;53(1):205-11.

57. Mellins RB, Evans D, Clark N, et al. Developing and communicating a long-term treatment plan for asthma. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(8):2419-28, 2433-4.

58. Rider EA, Keefer CH. Communication skills competencies: definitions and a teaching toolbox. Med Educ. 2006:40(7):624-9.

59. Kripalani S, Robertson R, Love-Ghaffari MH, et al. Development of an illustrated medication schedule as a low-literacy patient education tool. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):368-77.

60. Wolff K, Cavanaugh K, Malone R, et al. The diabetes literacy and numeracy education toolkit (DLNET): materials to facilitate diabetes education and management in patients with low literacy and numeracy skills. Diabetes Education. 2009;35(2):233-45.

61. Dunn RA, Shenouda PE, Martin DR, Schultz AJ. Videotape increases parent knowledge about poliovirus vaccines and choices of polio vaccination schedules. Pediatrics. 1998;102,e26.

62. Masley S, Sokoloff J, Hawes C. Planning group visits for high-risk patients. Fam Pract Manag. 2000;7(6):33-7.

63. Houck S, Kilo C, Scott JC. Improving patient care. Group visits 101. Fam Pract Manag. 2003;10(5):66-8.

64. Bunik M, Glazner JE, Chandramouli V, et al. Pediatric telephone call centers: how do they affect health care use and costs? Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):e305-13.

65. Gielen AC, McKenzie LB, McDonald EM, et al. Using a computer kiosk to promote child safety: results of a randomized, controlled trial in an urban pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics 2007;120(2):330-9.

66. Davis TC, Fredrickson DD, Bocchini C, et al. Improving vaccine risk/benefit communication with an immunization education package: a pilot study. Ambul Pediatr. 2000;2(3):193-200.

67. Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324(7341):827-30.

68. Rand CM, Conn KM, Crittenden CN, Halterman JS. Does a color-coded method for measuring acetaminophen doses reduce the likelihood of dosing error? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(7):625-7.

69. Frush KS, Luo X, Hutchinson P, Higgins JN. Evaluation of a method to reduce over-the-counter medication dosing error. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(7):620-4.

70. Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills, 2nd ed., Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1996.

71. Davis TC, Gazmararian J, Kennen EM. Approaches to improving health literacy: lessons from the field. J Health Commun. 2006;11(6):551-4.

72. Rich M. Health literacy via media literacy: video intervention/prevention assessment. American Behavioral Scientist. 2004;48(2):165-88.

73. Cooley WC, McAllister JW, Sherrieb K, Clark RE. The Medical Home Index: development and validation of a new practice-level measure of implementation of the Medical Home model. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(4):173-80.

74. Shaller D. Implementing and using quality measures for children’s health care: perspectives on the state of the practice. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 Pt 2):217-27.

75. National Health Education Standards PreK-12. 2nd ed. American Cancer Society. 2007.

76. Marx E, Hudson N, Deal TB, et al. Promoting health literacy through the health education assessment project. J Sch Health. 2007;77:157-63.

77. Golbeck AL, Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Paschal AM. Health Literacy and Adult Basic Education Assessments. Adult Basic Education: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Adult Literacy Educational Planning. 2005(15):151-68.

78. Kropsky JA, Keckly PH, Jensen PL. School-based obesity prevention programs: an evidence-based review. Obesity. 2008;16(5):1009-18.

79. Flynn BS, Worden JK, Secker-Walker RH, et al. Prevention of cigarette-smoking through mass-media intervention and school programs. Am J Publ Health. 1992;82(6):827-34.

80. Kolbe L, Kann L, Patterson B, et al. Enabling the nation’s schools to help prevent heart disease, stroke, cancer, COPD, diabetes, and other serious health problems. Pub Health Rep. 2004;119(3):286-302.

81. Kann L, Brener N, Wechsler H. Overview and summary: School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007;77(8):385-97.

82. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511-44.

83. Halfon N, DuPlessis N, Inkelas M. Transforming the U.S. Child Health System. Health Affairs. March/April 2007;26(2):315-29.

84. Arah OA, Westert GP, Hurst J, Klazing NS. A conceptual framework for the OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Project. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18 Suppl 1:5-13.

85. Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice. 1998;1(1):2-4.

86. Chew D, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588-94.

87. Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1995; 10(10):537-41.

88. Nurss J. Difficulties in Functional Health Literacy Screening in Spanish-Speaking Adults. Journal of Reading 1995;38(8):32-37.

89. Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med 1993;25(6):391-5.

90. Lee SY, Bender DE, Ruiz RE, Cho YI. Development of an easy-to-use Spanish health literacy test. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(4 Pt 1):1392-412.

91. Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

92. Wittich AR, Mangan J, Grad R, et al. Pediatric Asthma: Caregiver Health Literacy and the Clinician’s Perception. Journal of Asthma 2007; 44(1):51-5.

93. Schillinger D, Barton LR, Karter AJ, et al. Does literacy mediate the relationship between education and health outcomes? A study of a low-income population with diabetes. Public Health Reports. 2006;121(3):245-54.

94. Sanders LM, Rothman R, Franco V, et al. Low Parent Health Literacy is Associated with Poor Glycemic Control in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting, Honolulu, May 2008

95. DeWalt DA, Dilling MH, Rosenthal MS, Pignone MP. Low parental literacy is associated with worse asthma care measures in children. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:25-31.

96. Arnold CL, Davis TC, Berkel HJ. Smoking status, reading level, and knowledge of tobacco effects among low-income pregnant women. Prev Med. 2001;32:313-20.

97. Institute of Medicine. Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality. K Adams and J.M. Corrigan. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003.