2

Standards for Initiating a Systematic Review

Abstract: This chapter describes the initial steps in the systematic review (SR) process. The committee recommends eight standards for ensuring a focus on clinical and patient decision making and designing SRs that minimize bias: (1) establishing the review team; (2) ensuring user and stakeholder input; (3) managing bias and conflict of interest (COI) for both the research team and (4) the users and stakeholders participating in the review; (5) formulating the research topic; (6) writing the review protocol; (7) providing for peer review of the protocol; and (8) making the protocol publicly available. The team that will conduct the review should include individuals with appropriate expertise and perspectives. Creating a mechanism for users and stakeholders—consumers, clinicians, payers, and members of clinical practice guideline panels—to provide input into the SR process at multiple levels helps to ensure that the SR is focused on real-world healthcare decisions. However, a process should be in place to reduce the risk of bias and COI from user and stakeholder input and in the SR team. The importance of the review questions and analytic framework in guiding the entire review process demands a rigorous approach to formulating the research questions and analytic framework. Requiring a research protocol that prespecifies the research methods at the outset of the SR process helps prevent the effects of bias.

The initial steps in the systematic review (SR) process define the focus of the complete review and influence its ultimate use in making clinical decisions. Because SRs are conducted under varying circumstances, the initial steps are expected to vary across different reviews, although in all cases a review team should be established, user and stakeholder input gathered, the topic refined, and the review protocol formulated. Current practice falls far short of recommended guidance1; well-designed, well-executed SRs are the exception. At a workshop organized by the committee, representatives from professional specialty societies, consumers, and payers testified that existing SRs often fail to address questions that are important for real-world healthcare decisions.2 In addition, many SRs fail to develop comprehensive plans and protocols at the outset of the project, which may bias the reviews (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2007). As a consequence, the value of many SRs to healthcare decisions makers is limited.

The committee recommends eight standards for ensuring a focus on clinical and patient decision making and designing SRs that minimize bias. The standards pertain to: establishing the review team, ensuring user and stakeholder input, managing bias and conflict of interest (COI) for both the research team and users and stakeholders, formulating the research topic, writing the review protocol, providing for peer review of the protocol, and making the protocol publicly available. Each standard includes a set of requirements composed of elements of performance (Box 2-1). A standard is a process, action, or procedure for performing SRs that is deemed essential to producing scientifically valid, transparent, and reproducible results. A standard may be supported by scientific evidence; by a reasonable expectation that the standard helps to achieve the anticipated level of quality in an SR; or by the broad acceptance of the practice in SRs. Each standard includes elements of performance that the committee deems essential.

|

1 |

Unless otherwise noted, expert guidance refers to the published methods of the Evidence-based Practice Centers in the Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality Effective Health Care Program, the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (University of York, UK), and the Cochrane Collaboration. The committee also consulted experts at other organizations, including the Drug Effectiveness Review Project, the ECRI Institute, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (UK), and several Evidence-Based Practice Centers (with assistance from staff from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). See Appendix D for guidance. |

|

2 |

On January 14, 2010, the committee held a workshop that included four panels with representatives of organizations engaged in using and/or developing systematic reviews, including SR experts, professional specialty societies, payers, and consumer groups. See Appendix C for the complete workshop agenda. |

ESTABLISHING THE REVIEW TEAM

The review team is composed of the individuals who will manage and conduct the review. The objective of organizing the review team is to pull together a group of researchers as well as key users and stakeholders who have the necessary skills and clinical content knowledge to produce a high-quality SR. Many tasks in the SR process should be performed by multiple individuals with a range of expertise (e.g., searching for studies, understanding primary study methods and SR methods, synthesizing findings, performing meta-analysis). Perceptions of the review team’s trustworthiness and knowledge of real-world decision making are also important for the final product to be used confidently by patients and clinicians in healthcare decisions. The challenge is in identifying all of the required areas of expertise and selecting individuals with these skills who are neither conflicted nor biased and who are perceived as trustworthy by the public.

This section of the chapter presents the committee’s recommended standards for organizing the review team. It begins with background on issues that are most salient to setting standards for establishing the review team: the importance of a multidisciplinary review team, the role of the team leader, and bias and COI. The rationale for the recommended standards follows. Subsequent sections address standards for involving various users and stakeholders in the SR process, formulating the topic of the SR, and developing the SR protocol. The evidence base for these initial steps in the SR process is sparse. The committee developed the standards by reviewing existing expert guidance and weighing the alternatives according to the committee’s agreed-on criteria, especially the importance of improving the acceptability and patient-centeredness of publicly funded SRs (see Chapter 1 for a full discussion of the criteria).

A Multidisciplinary Review Team

The review team should be capable of defining the clinical question and performing the technical aspects of the review. It should be multidisciplinary, with experts in SR methodology, including risk of bias, study design, and data analysis; librarians or information specialists trained in searching bibliographic databases for SRs; and clinical content experts. Other relevant users and stakeholders should be included as feasible (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Slutsky et al., 2010). A single member of the review team can have multiple areas of expertise (e.g., SR methodology and quantitative analysis). The size of the team will depend on the number and com-

plexity of the question(s) being addressed. The number of individuals with a particular expertise needs to be carefully balanced so that one group of experts is not overly influential. For example, review teams that are too dominated by clinical content experts are more likely to hold preconceived opinions related to the topic of the SR,

Standard 2.6 Develop a systematic review protocol Required elements:

Standard 2.7 Submit the protocol for peer review Required element:

Standard 2.8 Make the final protocol publicly available, and add any amendments to the protocol in a timely fashion |

spend less time conducting the review, and produce lower quality SRs (Oxman and Guyatt, 1993).

Research examining dynamics in clinical practice guideline (CPG) groups suggests that the use of multidisciplinary groups is likely to lead to more objective decision making (Fretheim et al.,

2006a; Hutchings and Raine, 2006; Murphy et al., 1998; Shrier et al., 2008). These studies are relevant to SR teams because both the guideline development and the SR processes involve group dynamics and subjective judgments (Shrier et al., 2008). Murphy and colleagues (1998), for example, conducted an SR that compared judgments made by multi- versus single-disciplinary clinical guideline groups. They found that decision-making teams with diverse members consider a wider variety of alternatives and allow for more creative decision making compared with single disciplinary groups. In a 2006 update, Hutchings and Raine identified 22 studies examining the impact of group members’ specialty or profession on group decision making and found similar results (Hutchings and Raine, 2006). Guideline groups dominated by medical specialists were more likely to recommend techniques that involve their specialty than groups with more diverse expertise. Fretheim and colleagues (2006a) identified six additional studies that also indicated medical specialists have a lower threshold for recommending techniques that involve their specialty. Based on this research, a guideline team considering interventions to prevent hip fracture in the elderly, for example, should include family physicians, internists, orthopedists, social workers, and others likely to work with the patient population at risk.

The Team Leader

Minimal research and guidance have been done on the leadership of SR teams. The team leader’s most important qualifications are knowledge and experience in proper implementation of an SR protocol, and open-mindedness about the topics to be addressed in the review. The leader should also have a detailed understanding of the scope of work and be skilled at overseeing team discussions and meetings. SR teams rely on the team leader to act as the facilitator of group decision making (Fretheim et al., 2006b).

The SR team leader needs to be skilled at eliciting meaningful involvement of all team members in the SR process. A well-balanced and effective multidisciplinary SR team is one where every team member contributes (Fretheim et al., 2006b). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) directs individuals serving on its committees to be open to new ideas and willing to learn from one another (IOM, 2005). The role of the leader as facilitator is particularly important because SR team members vary in professional roles and depth of knowledge (Murphy et al., 1998). Pagliari and Grimshaw (2002) observed a multidisciplinary committee and found that the chair made the largest

contributions to group discussion and was pivotal in ensuring inclusion of the views of all parties. Team members with less specialization, such as primary care physicians and nurses, tended to be less active in the group discussion compared with medical specialists.

Bias and Conflicts of Interest

Minimizing bias and COI in the review team is important to ensure the acceptability, credibility, and scientific rigor of the SR.3 A recent IOM report, Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice, defined COI as “a set of circumstances that creates a risk that professional judgment or actions regarding a primary interest will be unduly influenced by a secondary interest” (IOM, 2009a, p. 46). Disclosure of individual financial, business, and professional interests is the established method of dealing with researchers’ COI (IOM, 2009a). A recent survey of high-impact medical journals found that 89 percent required authors to disclose COIs (Blum et al., 2009). The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recently created a universal disclosure form for all journals that are members of ICMJE to facilitate the disclosure process (Box 2-2) (Drazen et al., 2009, 2010; ICMJE, 2010). Leading guidance from producers of SRs also requires disclosure of competing interest (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Whitlock et al., 2010). The premise of disclosure policies is that reporting transparency allows readers to judge whether these conflicts may have influenced the results of the research. However, many authors fail to fully disclose their COI despite these disclosure policies (Chimonas et al., 2011; McPartland, 2009; Roundtree et al., 2008). Many journals only require disclosure of financial conflicts, and do not require researchers to disclose intellectual and professional biases that may be similarly influential (Blum et al., 2009).

Because of the importance of preventing bias from undermining the integrity of biomedical research, a move has been made to strengthen COI policies. The National Institutes of Health (NIH), for example, recently announced it is revising its policy for managing financial COI in biomedical research to improve compliance, strengthen oversight, and expand transparency in this area (Rockey and Collins, 2010). There is also a push toward defining COI to include potential biases beyond financial conflicts. The new ICMJE policy requires that authors disclose “any other relationships or

|

3 |

Elsewhere in this report, the term “bias” is used to refer to bias in reporting and publication (see Chapter 3). |

|

BOX 2-2 International Committee of Medical Journal Editors Types of Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures

SOURCE: ICMJE (2010). |

activities that readers could perceive to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing” the research, such as personal, professional, political, institutional, religious, or other associations (Drazen et al., 2009, 2010, p. 268). The Cochrane Collaboration also requires members of the review team to disclose “competing interests that they judge relevant” (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2006). Similarly, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), created by the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, will require individuals serving on the Board of Governors, the methodology committee, and expert advisory panels to disclose both financial and personal associations.4

Secondary interests, such as the pursuit of professional advancement, future funding opportunities, and recognition, and the desire to do favors for friends and colleagues, are also important potential conflicts (IOM, 2009a). Moreover, mere disclosure of a conflict does not resolve or eliminate it. Review teams should also evaluate and act on the disclosed information. Eliminating the relationship, further disclosure, or restricting the participation of a researcher with COI may be necessary. Bias and COI may also be minimized by creating review teams that are balanced across relevant expertise and perspectives as well as competing interests (IOM, 2009a). The Cochrane Collaboration, for example, requires that if a member of

the review team is an author of a study that is potentially eligible for the SR, there must be other members of the review team who were not involved in that study. In addition, if an SR is conducted by individuals employed by a pharmaceutical or device company that relates to the products of that company, the review team must be multidisciplinary, with the majority of the members not employed by the relevant company. Individuals with a direct financial interest in an intervention may not be a member of the review team conducting an SR of that intervention (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2006). Efforts to prevent COI in health research should focus on not only whether COI actually biased an individual, but also whether COI has the potential for bias or appearance of bias (IOM, 2009a).

RECOMMENDED STANDARDS FOR ORGANIZING THE REVIEW TEAM

The committee recommends two standards for organizing the review team:

Standard 2.1—Establish a team with appropriate expertise and experience to conduct the systematic review

Required elements:

|

2.1.1 |

Include expertise in pertinent clinical content areas |

|

2.1.2 |

Include expertise in systematic review methods |

|

2.1.3 |

Include expertise in searching for relevant evidence |

|

2.1.4 |

Include expertise in quantitative methods |

|

2.1.5 |

Include other expertise as appropriate |

Standard 2.2—Manage bias and conflict of interest (COI) of the team conducting the systematic review

Required elements:

|

2.2.1 |

Require each team member to disclose potential COI and professional or intellectual bias |

|

2.2.2 |

Exclude individuals with a clear financial conflict |

|

2.2.3 |

Exclude individuals whose professional or intellectual bias would diminish the credibility of the review in the eyes of the intended users |

Rationale

The team conducting the SR should include individuals skilled in group facilitation who can work effectively with a multidisciplinary review team, an information specialist, and individuals skilled in project management, writing, and editing (Fretheim et al., 2006a). In addition, at least one methodologist with formal training and

experience in conducting SRs should be on the team. Performance of SRs, like any form of biomedical research, requires education and training, including hands-on training (IOM, 2008). Each of the steps in conducting an SR should be, as much as possible, evidence based. Methodologists (e.g., epidemiologists, biostatisticians, health services researchers) perform much of the research on the conduct of SRs and are likely to stay up-to-date with the literature on methods. Their expertise includes decisions about study design and potential for bias and influence on findings, methods to minimize bias in the SR, qualitative synthesis, quantitative methods, and issues related to data collection and data management.

For SRs of comparative effectiveness research (CER), the team should include people with expertise in patient care and clinical decision making. In addition, as discussed in the following section, the team should have a clear and transparent process in place for obtaining input from consumers and other users and stakeholders to ensure that the review is relevant to patient concerns and useful for healthcare decisions. Single individuals might provide more than one area of required expertise. The exact composition of the review team should be determined by the clinical questions and context of the SR. The committee’s standard is consistent with guidance from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC), the United Kingdom’s Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), and the Cochrane Collaboration (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Slutsky et al., 2010). It is also integral to the committee’s criteria of scientific rigor by ensuring the review team has the skills necessary to conduct a high-quality SR.

The committee believes that minimizing COI and bias is critical to credibility and scientific rigor. Disclosure alone is insufficient. Individuals should be excluded from the review team if their participation would diminish public perception of the independence and integrity of the review. Individuals should be excluded for financial conflicts as well as for professional or intellectual bias. This is not to say that knowledgeable experts cannot participate. For example, it may be possible to include individual orthopedists in reviews of the efficacy of back surgery depending on the individual’s specific employment, sources of income, publications, and public image. Other orthopedists may have to be excluded if they may benefit from the conclusions of the SR or may undermine the credibility of the SR. This is consistent with the recent IOM recommendations (IOM, 2009a). However, this standard is stricter than all of the major organizations’ guidance on this topic, which emphasize disclosure of professional or intellectual bias, rather than requiring the exclusion of

individuals with this type of competing interest (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Slutsky et al., 2010). In addition, because SRs may take a year or more to produce, the SR team members should update their financial COI and personal biases at regular intervals.

ENSURING USER AND STAKEHOLDER INPUT

The target audience for SRs of CER include consumers, patients, and their caregivers; clinicians; payers; policy makers; private industry; organizations that develop quality indicators; SR sponsors; guideline developers; and others involved in “deciding what medical therapies and practice are approved, marketed, promoted, reimbursed, rewarded, or chosen by patients” (Atkins, 2007, p. S16). The purpose of CER, including SRs of CER, is to “assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers to make informed decisions that will improve health care at both the individual and populations levels” (IOM, 2009b, p. 41). Creating a clear and explicit mechanism for users and stakeholders to provide input into the SR process at multiple levels, beginning with formulating the research questions and analytic framework, is essential to achieving this purpose. A broad range of views should be considered in deciding on the scope of the SR. Often the organization(s) that nominate or sponsor an SR may be interested in specific populations, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes. Other users and stakeholders may bring a different perspective on the appropriate scope for a review. Research suggests that involving decision makers directly increases the relevance of SRs to decision making (Lavis et al., 2005; Schünemann et al., 2006).

Some SR teams convene formal advisory panels with representation from relevant user and stakeholder groups to obtain their input. Other SR teams include users and stakeholders on the review team, or use focus groups or conduct structured interviews with individuals to elicit input. Whichever model is used, the review team must include a skilled facilitator who can work effectively with consumers and other users and stakeholders to develop the questions and scope for the review. Users and stakeholders may have conflicting interests or very different ideas about what outcomes are relevant, as may other members of the review team, to the point that reconciling all of the different perspectives might be very challenging.

AHRQ has announced it will spend $10 million on establishing a Community Forum for CER to engage users and stakeholders formally, and to expand and standardize public involvement in the entire Effective Health Care Program (AHRQ, 2010). Funds will be

used to conduct methodological research on the involvement of users and stakeholders in study design, interpretation of results, development of products, and research dissemination. Funds also will be used to develop a formal process for user and stakeholder input, to convene community panels, and to establish a workgroup on CER to provide formal advice and guidance to AHRQ (AHRQ, 2010).

This section of the chapter presents the committee’s recommended standards for gathering user and stakeholder input in the review process. It begins with a discussion of some issues relevant to involving specific groups of users and stakeholders in the SR process: consumers, clinicians, payers, representatives of clinical practice guideline teams, and sponsors of reviews. There is little evidence available to support user and stakeholder involvement in SRs. However, the committee believes that user and stakeholder participation is essential to ensuring that SRs are patient centered and credible, and focus on real-world clinical questions.

Consumer Involvement

Consumer involvement is increasingly recognized as essential in CER. The IOM Committee on Comparative Effectiveness Research Prioritization recommended that “the CER program should fully involve consumers, patients, and caregivers in key aspects of CER, including strategic planning, priority setting, research proposal development, peer review, and dissemination” (IOM, 2009b, p. 143). It also urged that strategies be developed to engage and prepare consumers effectively for these activities (IOM, 2009b).

Despite the increasing emphasis on the importance of involving consumers in CER, little empiric evidence shows how to do this most effectively. To inform the development of standards for SRs, the IOM committee commissioned a paper to investigate what is known about consumer involvement in SRs in the United States and key international organizations.5 The study sampled 17 organizations and groups (“organizations”) that commission or conduct SRs (see Box 2-3 for a list of the organizations). Information about these organizations was retrieved from their websites and through semi-structured interviews with one or more key sources from each

|

BOX 2-3 Organizations and Groups Included in the Commissioned Paper on Consumer Involvement in Systematic Reviews Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality* American Academy of Pediatrics American College of Chest Physicians Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, Technology Evaluation Center Campbell Collaboration* Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Cochrane Collaboration (Steering Group)* Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group* Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group* ECRI Institute Hayes, Inc. Johns Hopkins Evidence-based Practice Center* Kaiser Permanente Mayo Clinic, Knowledge and Encounter Research Unit Office of Medical Applications of Research, National Institutes of Health Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center* U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs |

organization. Key sources for 7 of the 17 organizations (AHRQ, Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center, Johns Hopkins EPC, Campbell Collaboration, Cochrane Collaboration, Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group, and Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group) reported that their organization has a process in place to involve consumers on a regular basis. The other 10 organizations reported that their organizations do not usually involve consumers in the SR process, although some of them do so occasionally or they involve consumers regularly in other parts of their processes (e.g., when making coverage decisions).

The organizations that do involve consumers indicated a range of justifications for their procedures. For example, consumer involvement aims at ensuring that the research questions and outcomes included in the SR protocol reflect the perspectives and needs of the people who will receive the care and require this information to make real-world and optimally informed decisions. Several key sources noted that research questions and outcomes identified by consumers with a personal experience with the condition or treat-

ment being studied are often different from the questions and outcomes identified by researchers and clinicians.

Consumers have been involved in all stages of the SR process. Some key sources reported that consumers should be involved early in the SR process, such as in topic formulation and refinement and in identification of the research questions and outcomes. Others involve consumers in reviewing the draft protocol. However, some noted, by the time the draft protocol is ready for review, accommodating consumer comments may be difficult because so much has already been decided. Some organizations also involve consumers in reviewing the final report (see Chapter 5). A few organizations reported instances in which consumers have participated in the more technical and scientific steps of an SR process, or even authored an SR. However, these instances are rare, and some key sources indicated they believed involving consumers is not necessary in these aspects of the review.

The term “consumer” has no generally accepted definition. Organizations that involve consumers have included patients with a direct personal experience of the condition of interest, and spouses and other family members (including unpaid family caregivers) who have direct knowledge about the patient’s condition, treatment, and care. Involving family members and caregivers may be necessary in SRs studying patients who are unable to participate themselves because of cognitive impairment or for other reasons. However, family members and caregivers may also have different perspectives than patients about research questions and outcomes for an SR. Key sources reported that they have involved representatives from patient organizations as well as individual patients. The most important qualifications for the consumers to be involved in SRs—as pointed out by key sources—included a general interest, willingness to engage, and ability to participate.

The extent to which consumers are compensated for the time spent on SR activities depended on the organization and on the type of input the consumer provided. For example, in SRs commissioned by AHRQ, consumers who act as peer reviewers or who are involved in the process of translating the review results into consumer-friendly language are financially compensated for their time, generally at a fairly modest level. Other organizations do not provide any financial compensation. The form of involvement also differed across organizations, with, for example, consumers contributing as part of a user and stakeholder group, as part of an advisory group to a specific review or group of reviews, and as individuals.

A few organizations provide some initial orientation toward the review process or more advanced training in SR methodology for consumers, and one is currently developing training for researchers about how to involve or work with consumers and other stakeholders in the SR process.

Expert guidance on SRs generally recommends that consumers be involved in the SR process. The EPCs involve consumers in SRs for CER at various stages in the SR process, including in topic formulation and dissemination (Whitlock et al., 2010). Likewise, the Cochrane Collaboration encourages consumer involvement, either as part of the review team or in the editorial process (Higgins and Green, 2008). Both organizations acknowledge, however, that many questions about the most effective ways of involving consumers in the SR process remain unresolved (Higgins and Green, 2008; Whitlock et al., 2010).

Various concerns have been raised about involving consumers in the health research process (Entwistle et al., 1998). For example, some have argued that one consumer, or even a few consumers, cannot represent the full range of perspectives of all potential consumers of a given intervention (Bastian, 2005; Boote et al., 2002). Some consumers may not understand the complexities and rigor of research, and may require training and mentoring to be fully involved in the research process (Andejeski et al., 2002; Boote et al., 2002). Consumers may also have unrealistic expectations about the research process and what one individual research project can achieve. In addition, obtaining input from a large number of consumers may add considerably to the cost and amount of time required for a research project (Boote et al., 2002).

Based on this review of current practice, the committee concluded that although there are a variety of ways to involve consumers in the SR process, there are no clear standards for this involvement. However, gathering input from consumers, through some mechanism, is essential to CER. Teams conducting publicly funded SRs of CER should develop a process for gathering meaningful input from consumers and other users and stakeholders. The Cochrane Collaboration has conducted a review of its Consumer Network, which included process issues, and its newly hired consumer coordinator may undertake a close review of processes and impacts. The AHRQ Community Forum may also help establish more uniform standards in this area based on the results of methodological research addressing the most effective methods of involving consumers (AHRQ, 2010). In Chapter 6, the committee highlights the need for a formal

evaluation of the effectiveness of the various methods of consumer involvement currently in practice, and of the impact of consumer involvement on the quality of SRs.

Clinician Involvement

Clinicians (e.g., physicians, nurses, and others who examine, diagnose, and treat patients) rely on SRs to answer clinical questions and to understand the limitations of evidence for the outcomes of an intervention. Although there is little empirical evidence, common sense suggests that their participation in the SR process can increase the relevance of research questions to clinical practice, and help identify real-world healthcare questions. Clinicians have unique insights because of their experiences in treating and diagnosing illness and through interacting with patients, family members, and their caregivers. In addition, getting input from clinicians often elucidates assumptions underlying support for a particular intervention. Eliciting these assumptions and developing questions that address them are critical elements of scoping an SR.

If the review team seeks clinician input, the team should hear from individuals representing multiple disciplines and types of practices. Several studies suggest that clinical specialists tend to favor and advocate for procedures and interventions that they provide (Fretheim et al., 2006b; Hutchings and Raine, 2006). Evidence also suggests that primary care physicians are less inclined than specialists to rate medical procedures and interventions as appropriate care (Ayanian et al., 1998; Kahan et al., 1996). In addition, clinicians from tertiary care institutions may have perspectives that are very different from clinicians from community-based institutions (Srivastava et al., 2005).

Payer Involvement

The committee heard from representatives of several payers at its workshop6 and during a series of informal interviews with representatives from Aetna, Kaiser Permanente, Geisinger, Blue Cross and Blue Shield’s Technology Evaluation Center, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and the Veterans Health Administration. Many of these organizations rely on publicly available SRs for decision making. They use SRs to make evidence-based coverage determinations and medical benefit policy and to provide clinician and patient

|

6 |

See Appendix C. |

decision support. For example, if there is better evidence for the efficacy of a procedure in one clinical setting over another, then the coverage policy is likely to reflect this evidence. Similarly, payers use SRs to determine pharmaceutical reimbursement levels and to manage medical expenditures (e.g., by step therapy or requiring prior authorization). Obtaining input from individuals that represents the purchaser perspective is likely to improve the relevance of an SR’s questions and concerns.

Involvement of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Team

If an SR is a prerequisite to developing a CPG, it is important that the SR team be responsive to the questions of the CPG panel. There are various models of interaction between the CPG and SR teams in current practice, ranging from no overlap between the two groups (e.g., the NIH Consensus Development Conferences), to the SR and CPG teams interacting extensively during the evidence review and guideline writing stages (e.g., National Kidney Foundation [NKF], Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes), to numerous variations in between (e.g., American College of Chest Physicians [ACCP]) (Box 2-4). Table 2-1 describes three general models of interaction: more complete isolation, moderate, and unified. Each model has benefits and drawbacks. Although the models have not been formally evaluated, the committee believes that a moderate level of interaction is optimal because it establishes a mechanism for communication between the CPG panel and the SR team, while also protecting against inappropriate influence on the SR methods.

Separation of the SR and the CPG teams, such as the approach used by NIH Consensus Development Conferences to develop evidence-based consensus statements, may guard against the CPG panel interfering in the SR methods and interpretation, but at the risk of producing an SR that is unresponsive to the guidelines team’s questions. By shutting out the CPG panel from the SR process, particularly in the analysis of the evidence and preparation of the final report, this approach reduces the likelihood that the primary audience for the SR will understand the nuances of the existing evidence. The extreme alternative, unrestricted interaction between the review team and the guidelines team, or when the same individuals conduct the SR and write the CPG, risks biasing the SR and the review team is more likely to arrive at the answers the guideline team wants.

Some interaction, what the committee refers to as “moderate,” allows the SR team and the CPG team to maintain separate identities and to collaborate at various stages in the SR and guideline

|

BOX 2-4 Examples of Interaction Between Systematic Review (SR) and Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) Teams More Isolation: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Conferences

Moderate: American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP)

Unified: National Kidney Foundation, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

SOURCES: Guyatt et al. (2010); KDIGO (2010); NIH (2010). |

TABLE 2-1 Models of Interaction Between Systematic Review (SR) and Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) Teams

|

|

General Models of Interaction Between Developers of SRs and CPGs |

||

|

More Isolatation |

Moderate |

Unified |

|

|

Level of interaction |

|

|

|

|

Potential benefits |

|

|

|

|

Potential drawbacks |

|

|

|

development process. Moderate interaction can occur in numerous ways, including, for example, having one or more CPG liaison(s) regularly communicate with the SR team, holding joint meetings of the SR and CPG team, or including a CPG representative on the SR team. At this level of interaction, the CPG team has input into the SR topic formulation, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and organization of the review, but it does not have control over the methods and conclusions of the final SR report (see Chapter 5). The SR team can be available to answer the CPG team’s questions regarding the evidence during the drafting of the guideline. An additional example of moderate interaction is including members of the SR team on the CPG team. Some professional societies, such as the ACCP (see Box 2-4), allow both SR methodologists and clinical content experts from the CPG team to have input into preparing the SR report. Bias and COI is prevented because the SR methodologists, not the clinical content experts, have final responsibility for the interpretation and presentation of the evidence (Guyatt et al., 2010).

Sponsors of SRs

As discussed above, professional specialty societies and other private healthcare organizations, such as ACCP and NKF, often sponsor SRs to inform the development of CPGs. AHRQ and other government agencies also sponsor many SRs, as will PCORI, that are intended to inform patient and clinician decisions, but not specifically for a CPG. While an SR should respond to the sponsor’s questions, the sponsor should not overly influence the SR process. The relationship between the sponsor and the SR review team needs to be carefully managed to balance the competing goals of maintaining the scientific independence of the SR team and the need for oversight to ensure the quality and timeliness of their work.

To protect the scientific integrity of the SR process from sponsor interference, the types of interactions permitted between the sponsor and SR team should be negotiated and refined before the finalization of the protocol and the undertaking of the review. The sponsor should require adherence to SR standards, but should not impose requirements that may bias the review. Examples of appropriate mechanisms for managing the relationship include oversight by qualified project officers, an independent peer review process, and the use of grants as well as contracts for funding SRs. Qualified project officers at the sponsoring organization should have knowledge and experience about how to conduct an SR and a high internal standard of respect for science, and not interfere in the conduct of

the SR. An independent peer review process allows a neutral party to determine whether an SR follows appropriate scientific standards and is responsive to the needs of the sponsor. All feedback to the SR team should be firsthand via peer review. The use of grants and other mechanism to fund SRs allows the SR team to have more scientific independence in conducting the review than traditional contracts.

Sponsors should not be allowed to delay or prevent publication of an SR in a peer-reviewed journal and should not interfere with the journal’s peer review process. This promotes the committee’s criteria of transparency by making SR results widely available. The ICMJE publication requirements for industry-sponsored clinical trials should be extended to publicly funded SRs (ICMJE, 2007). Except where prohibited by a journal’s policies, it is reasonable for the authors to provide the sponsor with a copy of the proposed journal submission, perhaps with the possibility of the sponsor offering non-binding comments. If a paper is accepted by a journal after delivery of the final report, discrepancies between the journal article and the report may legitimately result from the journal’s peer review process. The agreement between the sponsor and the SR team should give the SR team complete freedom to publish despite any resulting discrepancies.

RECOMMENDED STANDARDS FOR ENSURING USER AND STAKEHOLDER INPUT

The committee recommends two standards for ensuring user and stakeholder input in the SR process:

Standard 2.3—Ensure user and stakeholder input as the review is designed and conducted

Required element:

|

2.3.1. |

Protect the independence of the review team to make the final decisions about the design, analysis, and reporting of the review |

Standard 2.4—Manage bias and COI for individuals providing input into the systematic review

Required elements:

|

2.4.1. |

Require individuals to disclose potential COI and professional or intellectual bias |

|

2.4.2. |

Exclude input from individuals whose COI or bias would diminish the credibility of the review in the eyes of the intended users |

Rationale

All SR processes should include a method for collecting feedback on research questions, topic formulation, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the organization of the SR from individuals with relevant perspectives and expertise. Users and stakeholders need not be consulted in interpreting the science, in drawing conclusions, or in conducting the technical aspects of the SR. User and stakeholder feedback can be collected through various techniques, such as a formal advisory group, the use of focus groups or structured interviews, the inclusion of users and stakeholders on the review team, or peer review. Various users and stakeholders bring different perspectives and priorities to the review, and these views should help shape the research question and outcomes to be evaluated so that they are more focused on clinical and patient-centered decision making. The EPCs, CRD, and Cochrane Collaboration experts recognize that engaging a range of users and stakeholders—such as consumers, clinicians, payers, and policy makers—is likely to make reviews of higher quality and more relevant to end users (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Whitlock et al., 2010). User and stakeholder involvement is also likely to improve the credibility of the review. The type of users and stakeholders important to consult, and the decision on whether to create a formal or informal advisory group, depend on the topic and circumstances of the SR.

Getting input from relevant CPG teams (as appropriate) and SR sponsors helps to ensure that SRs are responsive to these groups’ questions and needs. However, the independence of the review team needs to be protected to ensure that this feedback does not interfere with the scientific integrity of the review. This is consistent with guidance from the Cochrane Collaboration, which prohibits sponsorship by any commercial sources with financial interests in the conclusions of Cochrane reviews. It also states that sponsors should not be allowed to delay or prevent publication of a review, or interfere with the independence of the authors of reviews (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2006; Higgins and Green, 2008).

Avoiding bias and COI is as important for the users and stakeholders providing input into SR process as it is for those actually conducting the review. Individuals providing input should publicly acknowledge their potential biases and COI, and should be excluded from the review process if their participation would diminish the credibility of the review in the eyes of the intended user. In some cases, it may be possible to balance feedback from individuals with strong biases or COI across competing interests if their viewpoints

are important for the review team to consider. For example, users and stakeholders with strong financial and personal connections with industry should not participate in reviews. This is consistent with the EPC guidance, which requires that participants, consultants, subcontractors, and other technical experts disclose in writing any financial and professional interests that are related to the subject matter of the review (Slutsky et al., 2010). The next edition of the CRD guidance will also make explicit that users and stakeholders should declare all biases, and steps should be taken to ensure that these do not impact the review.7 In addition, as mentioned above, managing bias and COI is critical to transparency, credibility, and scientific rigor.

FORMULATING THE TOPIC

Informative and relevant SRs of CER require user and other stakeholder input as the review’s research questions are being developed and designed. CER questions should address diverse populations of study participants, examine interventions that are feasible to implement in a variety of healthcare settings, and measure a broad range of health outcomes (IOM, 2009b). Well-formulated questions are particularly important because the questions determine many other components of the review, including the search for studies, data extraction, synthesis, and presentation of findings (Counsell, 1997; Higgins and Green, 2008; IOM, 2008; Liberati et al., 2009).

Topic formulation, however, is a challenging process that often takes more time than expected. The research question should be precise so that the review team can structure the other components of the SR. To inform decision making, research questions should focus on the uncertainties that underlie disagreement in practice, and the outcomes and interventions that are of interest to patients and clinicians. Also important is ensuring that the research questions are addressing novel issues, and not duplicating existing SRs or other ongoing reviews (CRD, 2009; Whitlock et al., 2010).

Structured Questions

Well-formulated SR questions use a structured format to improve the scientific rigor of an SR, such as the PICO(TS) mnemonic: population, intervention, comparator, outcomes, timing, and

TABLE 2-2 PICO Format for Formulating an Evidence Question

|

PICO Component |

Tips for Building Question |

Example |

|

Patient population or problem |

“How would I describe this group of patients?” Balance precision with brevity |

“In patients with heart failure from dilated cardiomyopathy who are in sinus rhythm …” |

|

Intervention (a cause, prognostic factor, treatment, etc.) |

“Which main intervention is of interest?” Be specific |

“… would adding anticoagulation with warfarin to standard heart failure therapy …” |

|

Comparison intervention (if necessary) |

“What is the main alternative to be compared with the intervention?” Be specific |

“… when compared with standard therapy alone …” |

|

Outcomes |

“What do I hope the intervention will accomplish?” “What could this exposure really affect?” Be specific |

“… lead to lower mortality or morbidity from thromboembolism? Is this enough to be worth the increased risk of bleeding?” |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from the Evidence-based Practice Center Partner’s Guide (AHRQ, 2009). |

||

setting (Counsell, 1997; IOM, 2008; Richardson et al., 1995; Whitlock et al., 2010).8 Table 2-2 provides an example.

Identifying the population requires selecting the disease or condition of interest as well as specifying whether the review will focus on a specific subpopulation of individuals (e.g., by age, disease severity, existence of comorbidities). If there is good reason to believe a treatment may work differently in diverse subpopulations, the review protocol should structure the review so that these populations are examined separately. Focusing SRs on subgroups, such as individuals with comorbidities, can help to identify patients who are likely to benefit from an intervention in real-world clinical situations. SRs may address conditions and diseases that have the greatest impact on the health of the U.S. population, or on conditions and diseases that disproportionately and seriously affect subgroups and underserved members of the populations (IOM, 2009b).

For an SR to meet the definition of CER, it should compare at least two alternative interventions, treatments, or systems of care (IOM, 2009b). The interventions and comparators should enable patients and clinicians to balance the benefits and harms of potential treatment options. Cherkin and colleagues, for example, compared three treatment alternatives of interest to patients with lower back pain: physical therapy, chiropractic care, and self-care (Cherkin et al., 1998). The study found minimal differences between the treatments in terms of numbers of days of reduced activity or missed work, or in recurrences of back pain.

The SR should seek to address all outcomes that are important to patients and clinicians, including benefits, possible adverse effects, quality of life, symptom severity, satisfaction, and economic outcomes (IOM, 2009b; Schünemann et al., 2006; Tunis et al., 2003). Patients faced with choosing among alternative prostate cancer treatments, for example, may want to know not only prognosis, but also potential adverse effects such as urinary incontinence and impotence. The SR team should obtain a wide range of views about what outcomes are important to patients (Whitlock et al., 2010). Whether or not every outcome important to patients can actually be addressed in the review depends on whether those outcomes have been included in the primary studies.

If the research question includes timing of the outcome assessment and setting, this helps set the context for the SR. It also narrows the question, however, and the evidence examined is limited as a result. The timing should indicate the time of the intervention and of the follow-up, and the setting should indicate primary or specialty care, inpatient or outpatient treatment, and any cointerventions (Whitlock et al., 2010).

Analytic Framework

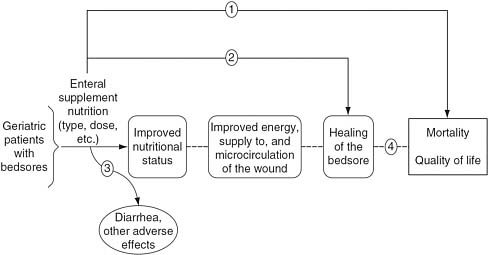

An analytic framework (also called “logic framework”) is helpful to developing and refining the SR topic, especially when more than one question is being asked. It should clearly define the relevant patient and contextual factors that might influence the outcomes or treatment effects and lay out the chain of logic underlying the mechanism by which each intervention may improve health outcomes (Harris et al., 2001; IOM, 2008; Mulrow et al., 1997; Sawaya et al., 2007; Whitlock et al., 2002; Woolf et al., 1996). This visual representation of the question clarifies the researchers’ assumptions about the relationships among the intervention, the intermediate outcomes (e.g., changes in levels of blood pressure or bone density),

FIGURE 2-1 Analytic framework for a new enteral supplement to heal bedsores.

SOURCE: Helfand and Balshem (2010).

and health outcomes (e.g., myocardial infarction and strokes). It can also help clarify the researchers’ implicit beliefs about the benefits of a healthcare intervention, such as quality of life, morbidity, and mortality (Helfand and Balshem, 2010). It increases the likelihood that all contributing elements in the causal chain will be examined and evaluated. However, the analytic framework diagram may need to evolve to accurately represent SRs of CER that compare alternative treatments and interventions.

Figure 2-1 shows an analytic framework for evaluating studies of a new enteral supplement to heal bedsores (Helfand and Balshem, 2010). On the left side of the analytic framework is the population of interest: geriatric patients with bedsores. Moving from left to right across the framework is the intervention (enteral supplement nutrition), intermediate outcomes (improved nutritional status, improved energy/blood supply to the wound, and healing of the bedsore), and final health outcomes of interest (reduction in mortality, quality of life). The lines with arrows represent the researchers’ questions that the evidence must answer at each phase of the review. The dotted lines indicate that the association between the intermediate outcomes and final health outcomes are unproven, and need to be linked by evaluating several bodies of evidence. The squiggly line denotes the question that addresses the harms of the intervention (e.g., diarrhea or other adverse effects). In this example, the lines and arrows represent the following key research questions:

|

Line 1 |

Does enteral supplementation improve mortality and quality of life? |

|

Line 2 |

Does enteral supplementation improve wound healing? |

|

Line 3 |

How frequent and severe are side effects such as diarrhea? |

|

Line 4 |

Is wound healing associated with improved survival and quality of life? |

Evidence that directly links the intervention to the final health outcome is the most influential (Arrow 1). Arrows 2 and 4 link the treatments to the final outcomes indirectly: from treatment to an intermediate outcome, and then, separately, from the intermediate outcome to the final health outcomes. The nutritional status and improved energy/blood supply to the wound are only important outcomes if they are in the causal pathway to improved healing, reduced mortality, and a better quality of life. The analytic framework does not have corresponding arrows to these intermediate outcomes because studies measuring these outcomes would only be included in the SR if they linked the intermediate outcome to healing, mortality, or quality of life.

RECOMMENDED STANDARDS FOR FORMULATING THE TOPIC

The importance of the research questions and analytic framework in determining the entire review process demands a rigorous approach to topic formulation. The committee recommends the following standard:

Standard 2.5—Formulate the topic for the systematic review

Required elements:

|

2.5.1 |

Confirm the need for a new review |

|

2.5.2 |

Develop an analytic framework that clearly lays out the chain of logic that links the health intervention to the outcomes of interest and defines the key clinical questions to be addressed by the systematic review |

|

2.5.3 |

Use a standard format to articulate each clinical question of interest |

|

2.5.4 |

State the rationale for each clinical question |

|

2.5.5 |

Refine each question based on user and stakeholder input |

Rationale

SRs of CER should focus on specific research questions using a structured format (e.g., PICO[TS]), an analytic framework, and a clear rationale for the research question. Expert guidance recommends using the PICO(TS) acronym to articulate research questions (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Whitlock et al., 2010). Developing an analytic framework is required by the EPCs to illustrate the chain of logic underlying the research questions (AHRQ, 2007; Helfand and Balshem, 2010; IOM, 2008). Using a structured approach and analytic framework also improves the scientific rigor and transparency of the review by requiring the review team to clearly articulate the clinical questions and basic assumptions in the SR.

The AHRQ EPC program, CRD, and the Cochrane Collaboration all have mechanisms for ensuring that new reviews cover novel and important topics. AHRQ, for example, specifically requires that topics have strong potential for improving health outcomes (Whitlock et al., 2010). CRD recommends that researchers undertaking reviews first search for existing or ongoing reviews and evaluate the quality of any reviews on similar topics (CRD, 2009). The Cochrane Collaboration review groups require approval by the “coordinating editor” (editor in chief) of the relevant review group for new SRs (Higgins and Green, 2008). Confirming the need for a new review is consistent with the committee’s criterion of efficiency because it prevents the burden and cost of conducting an unnecessary, duplicative SR (unless the “duplication” is considered necessary to improve on earlier efforts). If the SR registries now in development become fully operational, this requirement will become much easier for the review team to achieve in the near future (CRD, 2010; HHS, 2010; Joanna Briggs Institute, 2010; NPAF, 2011; PIPC, 2011).

DEVELOPING THE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROTOCOL

The SR protocol is a detailed description of the objectives and methods of the review (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Liberati et al., 2009). The protocol should include information regarding the context and rationale for the review, primary outcomes of interest, search strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria, data synthesis strategy, and other aspects of the research plan. The major challenge to writing a comprehensive research protocol is accurately specifying the research questions and methods before the study begins. Developing the protocol is an iterative process that requires communication with users and stakeholders, input from the general public, and a

preliminary review of the literature before all of the components of the protocol are finalized (CRD, 2009). Researchers’ decisions to undertake an SR may be influenced by prior knowledge of results of available studies. The inclusion of multiple perspectives on the review team and gathering user and stakeholder input helps prevent choices in the protocol that are based on such prior knowledge.

The use of protocols in SRs is increasing, but is still not standard practice. A survey of SRs indexed in MEDLINE in November, 2004 found that 46 percent of the reviews reported using a protocol (Moher et al., 2007), a significant rise from only 7 percent of reviews in an earlier survey (Sacks et al., 1987).

Publication of the Protocol

A protocol should be made publicly available at the start of an SR in order to prevent the effects of author bias, allow feedback at an early stage in the SR, and tell readers of the review about protocol changes that occur as the SR develops. It also gives the public the chance to examine how well the SR team has used input from consumers, clinicians, and other experts to develop the questions and PICO(TS) the review will address. In addition, a publicly available protocol has the benefit that other researchers can identify ongoing reviews, and thus avoids unnecessary duplication and encourages collaboration. This transparency may provide an opportunity for methodological and other research (see Chapter 6) (CRD, 2010).

One of the most efficient ways to publish protocols is through an SR protocol electronic registration. However, more than 80 percent of SRs are conducted by organizations that do not have existing registries (CRD, 2010). The Cochrane Collaboration and AHRQ have created their own infrastructure for publishing protocols (Higgins and Green, 2008; Slutsky et al., 2010). Review teams conducting SRs funded through PCORI9 will also be required to post research protocols on a government website at the outset of the SR process.

Several electronic registries under development intend to publish all SR protocols, regardless of the funding source (CRD, 2010; Joanna Briggs Institute, 2010). CRD is developing an international registry of ongoing health-related SRs that will be open to all prospective registrations and will offer free public access for electronic searching. Each research protocol will be assigned a unique identifi-

cation number, and an audit trail of amendments will be part of each protocol’s record. The protocol records will also link to the resulting publication. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement reflects the growing recognition of the importance of prospective registration of protocols, and requires that published SRs indicate whether a review protocol exists and if and where it can accessed (e.g., web address), and the registration information and number (Liberati et al., 2009).

Amendments to the Protocol

Often the review team needs to make amendments to a protocol after the start of the review that result from the researchers’ improved understanding of the research questions or the availability of pertinent evidence (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Liberati et al., 2009). Common amendments include extending the period of the search to include older or newer studies, broadening eligibility criteria, and adding new analyses suggested by the primary analysis (Liberati et al., 2009). Researchers should document such amendments with an explanation for the change in the protocol and completed review (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Liberati et al., 2009).

In general, researchers should not modify the protocol based on knowledge of the results of analyses. This has the potential to bias the SR, for example, if the SR omits a prespecified comparison when the data indicate that an intervention is more or less effective than the retained comparisons. Similar problems occur when researchers modify the protocol by adding or deleting certain study designs or outcome measures, or change the search strategy based on prior knowledge of the data. Researchers may be motivated to delete an outcome when its results do not match the results of the other outcome measures (Silagy et al., 2002), or to add an outcome that had not been prespecified. Publishing the protocol and amendments allows readers to track the changes and judge whether an amendment has biased the review. The final SR report should also identify those analyses that were prespecified and those that were not, and any analyses requested by peer reviewers (see Chapter 5).

RECOMMENDED STANDARDS FOR DEVELOPING THE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROTOCOL

The committee recommends three standards related to the SR protocol:

Standard 2.6—Develop a systematic review protocol

Required elements:

|

2.6.1 |

Describe the context and rationale for the review from both a decision-making and research perspective |

|

2.6.2 |

Describe the study screening and selection criteria (inclusion/exclusion criteria) |

|

2.6.3 |

Describe precisely which outcome measures, time points, interventions, and comparison groups will be addressed |

|

2.6.4 |

Describe the search strategy for identifying relevant evidence |

|

2.6.5 |

Describe the procedures for study selection |

|

2.6.6 |

Describe the data extraction strategy |

|

2.6.7 |

Describe the process for identifying and resolving disagreement between researchers in study selection and data extraction decisions |

|

2.6.8 |

Describe the approach to critically appraising individual studies |

|

2.6.9 |

Describe the method for evaluating the body of evidence, including the quantitative and qualitative synthesis strategy |

|

2.6.10 |

Describe and justify any planned analyses of differential treatment effects according to patient subgroups, how an intervention is delivered, or how an outcome is measured |

|

2.6.11 |

Describe the proposed timetable for conducting the review |

Standard 2.7—Submit the protocol for peer review

Required element:

|

2.7.1 |

Provide a public comment period for the protocol and publicly report on disposition of comments |

Standard 2.8—Make the final protocol publicly available, and add any amendments to the protocol in a timely fashion

Rationale

The majority of these required elements are consistent with leading guidance, and ensure that the protocol provides a detailed description of the objectives and methods of the review (AHRQ,

2009; CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008).10 The committee added the requirement to identify and justify planned subgroup analyses to examine whether treatment effects vary according to patient group, the method of providing the intervention, or the approach to measuring an outcome, because evidence on variability in treatment effects across subpopulations is key to directing interventions to the most appropriate populations. The legislation establishing PCORI requires that “research shall be designed, as appropriate, to take into account the potential for differences in the effectiveness of healthcare treatments, services, and items as used with various subpopulations, such as racial and ethnic minorities, women, age, and groups of individuals with different comorbidities, genetic and molecular subtypes, or quality of life preferences.”11 The protocol should state a hypothesis that justifies the planned subgroup analyses, including the direction of the suspected subgroup effects, to reduce the possibility of identifying false subgroup effects. The subgroup analyses should also be limited to a small number of hypothesized effects (Sun et al., 2010). The committee also added the requirement that the protocol include the proposed timetable for conducting the review because this improves the transparency, efficiency, and timeliness of publicly funded SRs.

The draft protocol should be reviewed by clinical and methodological experts as well as relevant users and stakeholders identified by the review team and sponsor. For publicly funded reviews, the public should also have the opportunity to comment on the protocol to improve the acceptability and transparency of the SR process. The review team should be responsive to peer reviewers and public comments and publicly report on the disposition of the comments. The review team need not provide a public response to every question; it can group questions into general topic areas for response. The period for peer review and public comment should be specified so that the review process does not delay the entire SR process.

Cochrane requires peer review of protocols (Higgins and Green, 2008). The EPC program requires that the SR research questions and protocol be available for public comment (Whitlock et al., 2010).12 All of the leading guidance requires that the final protocol be pub-

|

10 |

The elements are all discussed in more detail in Chapters 3 through 5. |

|

11 |

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148, 111th Cong., Subtitle D, § 6301(d)(2)(D) (March 23, 2010). |

|

12 |

Information on making the protocol public comes from Mark Helfand, Director, Oregon Evidence-Based Practice Center, Professor of Medicine and Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon. |

licly available (CRD, 2009; Higgins and Green, 2008; Whitlock et al., 2010).

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2007. Methods reference guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews, Version 1.0. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

AHRQ. 2009. AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Centers partner’s guide. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

AHRQ. 2010. Reinvestment Act investments in comparative effectiveness research for a citizen forum. Rockville, MD: AHRQ. http://ftp.ahrq.gov/fund/cerfactsheets/cerfsforum.htm (accessed August 30, 2010).

Andejeski, Y., E. S. Breslau, E. Hart, N. Lythcott, L. Alexander, I. Rich, I. Bisceglio, H. S. Smith, and F. M. Visco. 2002. Benefits and drawbacks of including consumer reviewers in the scientific merit review of breast cancer research. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine 11(2):119–136.

Atkins, D. 2007. Creating and synthesizing evidence with decision makers in mind: Integrating evidence from clinical trials and other study designs. Medical Care 45(10 Suppl 2):S16–S22.

Ayanian, J. Z., M. B. Landrum, S. T. Normand, E. Guadagnoli, and B. J. McNeil. 1998. Rating the appropriateness of coronary angiography—Do practicing physicians agree with an expert panel and with each other? New England Journal of Medicine 338(26):1896–1904.

Bastian, H. 2005. Consumer and researcher collaboration in trials: Filling the gaps. Clinical Trials 2(1):3–4.

Blum, J. A., K. Freeman, R. C. Dart, and R. J. Cooper. 2009. Requirements and definitions in conflict of interest policies of medical journals. JAMA 302(20):2230–2234.

Boote, J., R. Telford, and C. Cooper. 2002. Consumer involvement in health research: A review and research agenda. Health Policy 61(2):213–236.

Cherkin, D. C., R. A. Deyo, M. Battié, J. Street, and W. Barlow. 1998. A comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for the treatment of patients with low back pain. New England Journal of Medicine 339(15):1021–1029.

Chimonas, S., Z. Frosch, and D. J. Rothman. 2011. From disclosure to transparency: The use of company payment data. Archives of Internal Medicine 171(1):81–86.

The Cochrane Collaboration. 2006. Commercial sponsorship and The Cochrane Collaboration. http://www.cochrane.org/about-us/commercial-sponsorship (accessed January 11, 2011).

Counsell, C. 1997. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine 127(5):380–387.

CRD (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination). 2009. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York, UK: York Publishing Services, Ltd.

CRD. 2010. Register of ongoing systematic reviews. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/projects/register.htm (accessed June 17, 2010).

Drazen, J., M. B. Van Der Weyden, P. Sahni, J. Rosenberg, A. Marusic, C. Laine, S. Kotzin, R. Horton, P. C. Hebert, C. Haug, F. Godlee, F. A. Frozelle, P. W. Leeuw, and C. D. DeAngelis. 2009. Uniform format for disclosure of competing interests in ICMJE journals. New England Journal of Medicine 361(19):1896–1897.

Drazen, J. M., P. W. de Leeuw, C. Laine, C. D. Mulrow, C. D. DeAngelis, F. A. Frizelle, F. Godlee, C. Haug, P. C. Hébert, A. James, S. Kotzin, A. Marusic, H. Reyes, J. Rosenberg, P. Sahni, M. B. Van Der Weyden, and G. Zhaori. 2010. Toward more uniform conflict disclosures: The updated ICMJE conflict of interest reporting form. Annals of Internal Medicine 153(4):268–269.

Entwistle, V. A., M. J. Renfrew, S. Yearley, J. Forrester, and T. Lamont. 1998. Lay perspectives: Advantages for health research. BMJ 316(7129):463–466.

Fretheim, A., H. J. Schünemann, and A. D. Oxman. 2006a. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: Group composition and consultation process. Health Research Policy and Systems 4:15.

Fretheim, A., H. J. Schünemann, and A. D. Oxman. 2006b. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: Group processes. Health Research Policy and Systems 4:17.

Guyatt, G., E. A. Akl, J. Hirsh, C. Kearon, M. Crowther, D. Gutterman, S. Z. Lewis, I. Nathanson, R. Jaeschke, and H. Schünemann. 2010. The vexing problem of guidelines and conflict of interest: A potential solution. Annals of Internal Medicine 152(11):738–741.

Harris, R. P., M. Helfand, S. H. Woolf, K. N. Lohr, C. D. Mulrow, S. M. Teutsch, D. Atkins, and Methods Work Group Third U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2001. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: A review of the process. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 20(Suppl 3): 21–35.

Helfand, M., and H. Balshem. 2010. AHRQ Series Paper 2: Principles for developing guidance: AHRQ and the Effective Health-Care Program. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63(5):484–490.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2010. Request for Information on development of an inventory of comparative effectiveness research. Federal Register 75 (137):41867–41868.

Higgins, J. P. T., and S. Green, eds. 2008. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Hutchings, A., and R. Raine. 2006. A systematic review of factors affecting the judgments produced by formal consensus development methods in health care. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 11(3):172–179.

ICMJE (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors). 2007. Sponsorship, authorship, and accountability. http://www.icmje.org/update_sponsor.html (accessed September 8, 2010).

ICMJE. 2010. ICMJE uniform disclosure form for potential conflicts of interest. http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (accessed January 11, 2011).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2005. Getting to know the committee process. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2008. Knowing what works in health care: A roadmap for the nation. Edited by J. Eden, B. Wheatley, B. McNeil, and H. Sox. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009a. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. Edited by B. Lo and M. Field. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009b. Initial national priorities for comparative effectiveness research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Joanna Briggs Institute. 2010. Protocols and works in progress. Adelaide, Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute. http://www.joannabriggs.edu.au/pubs/systematic_reviews_prot.php (accessed June 17, 2010).

Kahan, J. P., R. E. Park, L. L. Leape, S. J. Bernstein, L. H. Hilborne, L. Parker, C. J. Kamberg, D. J. Ballard, and R. H. Brooke. 1996. Variations in specialty in physician ratings of the appropriateness and necessity of indications for procedures. Medical Care 34(6):512–523.

KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes). 2010. Clinical practice guidelines. http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/guideline_development_process.php (accessed July 16, 2010).

Lavis, J., H. Davies, A. Oxman, J. L. Denis, K. Golden-Biddle, and E. Ferlie. 2005. Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policy-making. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10(Suppl 1):35–48.

Liberati, A., D. G. Altman, J. Tetzlaff, C. Mulrow, P. C. Gotzsche, J. Ioannidis, M. Clarke, P. J. Devereaux, J. Kleijnen, and D. Moher. 2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine 151(4):W1–W30.

McPartland, J. M. 2009. Obesity, the endocannabinoid system, and bias arising from pharmaceutical sponsorship. PLoS One 4(3):e5092.

Moher, D., J. Tetzlaff, A. C. Tricco, M. Sampson, and D. G. Altman. 2007. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLoS Medicine 4(3): 447–455.

Mulrow, C., P. Langhorne, and J. Grimshaw. 1997. Integrating heterogeneous pieces of evidence in systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine 127(11):989–995.

Murphy, M. K., N. A. Black, D. L. Lamping, C. M. McKee, C. F. Sanderson, J. Askham, and T. Marteur. 1998. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technology Assessment 2(3):1–88.

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2010. The NIH Consensus Development Program. Kensington, MD: NIH Consensus Development Program Information Center. http://consensus.nih.gov/aboutcdp.htm (accessed July 16, 2010).

NPAF (National Patient Advocate Foundation). 2011. National Patient Advocate Foundation launches Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) Database. http://www.npaf. org/images/pdf/news/NPAF_CER_010611.pdf (accessed February 1, 2011).

Oxman, A., and G. Guyatt. 1993. The science of reviewing research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 703:125–133.

Pagliari, C., and J. Grimshaw. 2002. Impact of group structure and process on multidisciplinary evidence-based guideline development: An observational study. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 8(2):145–153.

PIPC (Partnership to Improve Patient Care). 2011. Welcome to the CER Inventory. http://www.cerinventory.org/ (accessed February 1, 2011).

Richardson, W. S., M. S. Wilson, J. Mishikawa, and R. S. A. Hayward. 1995. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence based decisions. ACP Journal Club 123(3):A12–A13.

Rockey, S. J., and F. S. Collins. 2010. Managing financial conflict of interest in biomedical research. JAMA 303(23):2400–2402.

Roundtree, A. K., M. A. Kallen, M. A. Lopez-Olivo, B. Kimmel, B. Skidmore, Z. Ortiz, V. Cox, and M. E. Suarez-Almazor. 2008. Poor reporting of search strategy and conflict of interest in over 250 narrative and systematic reviews of two biologic agents in arthritis: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 62(2):128–137.

Sacks, H. S., J. Berrier, D. Reitman, V. A. Ancona-Berk, and T. C. Chalmers. 1987. Metaanalyses of randomized controlled trials. New England Journal of Medicine 316(8):450–455.

Sawaya, G. F., J. Guirguis-Blake, M. LeFevre, R. Harris, D. Petitti, and for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2007. Update on the methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Estimating certainty and magnitude of net benefit. Annals of Internal Medicine 147(12):871–875.

Schünemann, H. J., A. Fretheim, and A. D. Oxman. 2006. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: Grading evidence and recommendations. Health Research Policy Systems 4:21.

Shrier, I., J. Boivin, R. Platt, R. Steele, J. Brophy, F. Carnevale, M. Eisenberg, A. Furlan, R. Kakuma, M. Macdonald, L. Pilote, and M. Rossignol. 2008. The interpretation of systematic reviews with meta-analyses: An objective or subjective process? BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 8(1):19.

Silagy, C. A., P. Middelton, and S. Hopewell. 2002. Publishing protocols of systematic reviews: Comparing what was done to what was planned. JAMA 287(21):2831–2834.