4

Studying Family Processes in the Clinical and Prevention Sciences

The clinical and prevention sciences address the treatment and early roots of psychopathology. These areas of research, no less than others, are being transformed by the recent developments in methods and disciplines in family research. This chapter focuses on clinical and prevention research addressing three problems: trauma in young children, depression in parents, and substance abuse among fathers.

Different disciplines tend to approach psychopathology and its relationship to normative processes and development in different ways. Family research is central to much of this research. For example, the family roots of child, adolescent, and adult psychopathology have been central to mental health research for over a century. As family research methods have diversified, so has the richness of this work. Research on trauma presents an excellent example of such family and contextual influences. In prevention science, many of the recent advances have been driven by new ways to examine the risk and protective processes in families that represent productive targets of programs to prevent psychopathology and promote wellness and health.

By examining three different types of psychopathology and influences on it from varying disciplinary perspectives, this chapter points toward the benefits that can accrue by building bridges between disciplines. By taking advantage of complementary expertise, multidisciplinary work can yield results that could not be achieved through research in a single disciplinary tradition.

RESEARCH WITH FAMILIES INVOLVED WITH CHILD TRAUMA: CHALLENGES AND STRATEGIES

At San Francisco General Hospital, Chandra Ghosh Ippen, associate research director of the Child Trauma Research Program at the University of California, San Francisco, works with children ages zero to 6 who have experienced severe trauma. Her specialty is working with children whose parents have been murdered and with children who have been the victims of sexual abuse. At the workshop, she told the story of one young boy named Armando. At 5 years of age, Armando has serious speech and language delays. His mother says he was always an odd kid, and his teacher echoes that. She says she is worried about whether she can keep him in the classroom. He seems very tangential. More important, he does disturbing things with scissors, trying to cut himself or other people.

When Armando was less than a year old, he was left in the care of some relatives and was burned severely on his fingertips while they were drinking. When Child Protective Services became involved, the caseworkers found that his mother had a history of drinking, and he was removed from the home and placed in foster care. As more was learned about his history, it became clear that he had witnessed domestic violence between his parents. Ultimately, his mother returned and went into treatment, wanting to reunite with her son. She is an immigrant from Nicaragua and lived through the conflict there. She saw her own mother killed with a machete and then cared for her brother when he was young. “You can imagine these clinical processes affecting what we are seeing today,” said Ghosh Ippen. “The mother who perhaps does not care so well for the child. The child who triggers her because he reminds her of her brother whom she was caring for. This little boy who is carrying around this story. . . . This is the clinical reality that underlies the research picture that we have all been trying to study.”

Childhood trauma is an epidemic in the United States, especially in the age range from zero to 6. According to recent studies, 15.5 million children in the United States—1 in 5—live in families with partner violence (McDonald et al., 2006). Certain populations, including some ethnic minorities and people living in poverty, are more highly affected.

Younger children are more likely to be exposed to domestic violence than older children (Fantuzzo and Fusco, 2007). In the Minnesota Parent-Child Project, a 25-year longitudinal study of mothers and children in poverty, 12 percent of mothers reported mild partner violence and 25 percent reported severe partner violence when children were ages 18 to 64 months (Yates et al., 2003). In 2008, 3.7 million children were investigated for exposure to maltreatment, and 772,000 were considered to be victims of maltreatment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). More than half of these maltreated children are less than 7 years old.

Young children are also exposed to violence in the community. In a study conducted in Boston of nonreferred children ages 3 to 5 years, 42 percent had seen at least one violent event, 21 percent had seen three or more, and 12 percent had seen eight or more (Linares et al., 2001). In a Washington, DC, study of Head Start, 67 percent of parents and 78 percent of children reported that they had witnessed or had been a victim of at least one incident of violence (Shahinfar et al., 2000). “Young children are often victims in this epidemic,” said Ghosh Ippen. “We know that their physiology is being rampantly affected. We know that this is affecting brain development during a period of rapid brain development, at a time when the [hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal] axis and stress response are being formed.”

To address this problem, the origins and consequences of violence need to be understood on multiple levels, said Ghosh Ippen. The effects of violence on the developmental trajectory of children need to be studied and understood, as does the role of a child’s temperament. In addition, violence needs to be understood across generations and over the course of history.

“Little kids always walk in the presence of big feet,” said Ghosh Ippen. The best predictor of children’s functioning across multiple studies in multiple cultures is parents’ functioning, she said. For example, when a stressful event occurs, is a mother able to soothe an infant, or is she incapable of doing so? “The way the parent interprets what is happening, the way that they can soothe the child, that relationship is what affects the child.”

In conducting clinical work and research with trauma-exposed children, Ghosh Ippen considers primary risk factors, protective factors, change agents, and outcomes in the context of the child, the primary caregiver, and the social environment. The primary risk factor is the history of trauma, and the primary protective factor is the parent-child relationship. To assess for trauma, relevant factors include the type of event, the age at trauma, the severity of trauma, whether the trauma is acute or chronic, the relationship of the victim to the perpetrator, the reminders of the trauma, and protective factors.

From a clinical perspective, an important consideration is how the caregiver talks about the experience. Does the caregiver believe that the child remembers what happened? What is the caregiver’s affect? Or is the caregiver somehow disconnected from the experience?

Symptoms to be assessed include those of posttraumatic stress disorder (although this can be difficult to interpret in young children), oppositional defiant disorder, separation anxiety disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, or anxiety. Again, an important clini-

cal focus is why the caregiver thinks the child has these symptoms and the caregiver’s response to those symptoms.

Examples of traditional relationship constructs include warmth, responsiveness, affect (such as anger or frustration), limit setting, and the level of stress in a relationship. But there are also examples of newer, clinically based constructs, such as the caregiver as a protective shield, the ability to make meaning jointly about what has happened, or dyadic affect regulation.

To assess the trauma history, the functioning of the child, and relationships, Ghosh Ippen and her colleagues use a variety of measures, none of which is perfect. One challenge in the use of these measures is inaccurate responding. A caregiver may not trust a clinician, or a caregiver may have a reduced capacity to see a child’s perspective. “Armando’s mom has had over 13 traumatic and stressful life events,” said Ghosh Ippen. “She is an immigrant woman coming to see us. Does she view it as safe to tell us her history? Does she view it as safe to say that Armando has problems? Does she view it as safe to get help? These are some of the questions that might come up.”

In another case, a child could not even pick up a toy at the end of an assessment, saying that the stuffed lion would bite him, that the car would run over him, and that the balloon would float him away to heaven. It was clear, said Ghosh Ippen, that this mother could not focus on his symptoms because she was so focused on her own. “She had numbed out.”

Also, caregivers with multiple traumas sometimes can have affect charged, for example, by intrusive memories of the trauma. To overcome these barriers, it is essential to establish rapport—but rapid assessments make it difficult to do so. “From either a clinical perspective or a research perspective, you have got to have a relationship with this person to get an accurate read.”

Another challenge is that questionnaires can be long and burdensome. They need to balance internal consistency with the threat to validity from the burden. Many instruments, in order to maximize internal consistency, ask about a symptom in many different ways. This is a problem, especially with low-education immigrant families. With these families, clinicians have to read the instruments, and it can be awkward to ask the same question over and over. Caregivers also may have trauma symptoms that interfere with their responses. For example, avoidance is a core aspect of posttraumatic stress disorder.

To manage this burden, questionnaires need to be developed with input from a clinical perspective. Often, research questionnaires are applied to clinical work. It would be helpful to have measures developed for clinical use that also provide research data. Helpful modifications include the use of gating questions succeeded by follow-up

questions when appropriate. It also would be helpful to think about balancing the need for multiple items to obtain internal consistency with reducing the level of burden. It may be better clinically to organize items around the way people think, not according to diagnostic criteria. With measures of posttraumatic stress disorder, for example, the sleep items are separate rather than clumped together; it would make much more sense to ask people about similar behaviors at the same time.

Some items need to be worded more colloquially. A question such as whether a child has any re-experiencing symptoms is hard for most people to understand. Of course, most interviewers train clinicians to ask it a different way if the person does not understand the item, but it would be better if items were worded in ways that maximize the likelihood that people will understand them.

Researchers and clinicians need to think creatively about using physical objects that can be manipulated. People who have experienced trauma may be able to track and respond better when they are not only responding verbally.

Development challenges include how adults perceive young children and their behavior given different ages, cultures, and contexts. For example, a measure may not cut across age ranges, requiring different measures for different developmental stages. As a child develops, the capacity to process what happened and to communicate distress changes. How does this affect research? And how can distress be measured in babies and toddlers to determine whether they need treatment?

Research is done to affect clinical practice, but clinicians need to be able to use the tools that are developed. For example, it would be helpful for trauma screening to be more procedural, allow for consistency in how trauma history is assessed, and provide wording that allows for more valid responses. At the same time, many clinicians are not comfortable talking about trauma. Instruments need to be developed that they are comfortable using, and they need training to be able to use those instruments comfortably. “We need to think of the needs of clinicians and families along with the needs of research. We need contextually informed scientist-practitioner assessment tools.”

CONDUCTING RESEARCH WITH FAMILIES WITH MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES FROM A PREVENTIVE AND RESILIENCE-BASED PERSPECTIVE

A strong knowledge base exists for family-centered strength-based preventive intervention across a wide array of conditions, said William Beardslee, professor of child psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Baer Prevention Initiatives in the Department of Psychia-

try at Children’s Hospital of Boston. The best way to understand mental health processes is to identify ways to enhance resilience factors and diminish risk factors to test conceptual models. “All of us who engage in risk research are ultimately interested in doing interventions that will better the lives of children, and preventive interventions are usually the most effective,” he said.

Beardslee summarized the conclusions of two recent reports from the National Research Council–Institute of Medicine: one on depression among parents (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009a) and one on preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009b). Depression is a highly prevalent and impairing problem that affects 20 percent of adults in their lifetimes. Rates of depression vary by age, ethnicity, sex, and marital status, but many adults who suffer from depression are parents. According to estimates made by the committee that produced the report, 7.5 million parents in the United States are affected by depression each year.

Probably the best treatments in mental health are available for depression. Yet 40 to 70 percent of the adults who experience depression do not get treatment. “If I were standing here today and said we have 40 to 70 percent of adults not getting treatment for cancer, that would not be tolerated. So we need to attend to that issue,” Beardslee commented.

Depression among parents leads to sustained individual, family, and societal costs. For parents, depression can interfere with parenting quality and put children at risk for impaired health and poor development at all ages. Depression among parents affects employment, human capital, household production, parenting, and social capital, all of which have effects on children. And in the past year in the United States, at least 15.6 million children lived with an adult who had major depression.

Effective screening tools are available to identify adults with depression, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended screening for all adults once a year for depression. However, current screening programs in adults generally do not consider whether the adult is a parent, consider the impact of a parent’s mental health status on the health and development of their children, or integrate screening with further evaluation and treatment. Also, settings that serve parents at higher risk for depression do not routinely screen for prevention.

In terms of treatment, a variety of safe and effective tools exist for treating adults with elevated symptoms or major depression. Medications are useful for some people. There is strong evidence base about the talking therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and interpersonal therapy. There is a fairly strong evidence base about alternative treatments, such as meditation; however, evidence on the safety and efficacy of treatment

tools and strategies generally do not target parents or measure impact on parent functioning or child outcomes (except for pregnancy and for mothers postpartum), Beardslee said. “I would go further than that. I think that the best way to reach parents who are depressed is not so much around their depression but around helping them to be more effective parents. That is what they care most about. I think if we oriented our health care that way, we would be more effective.”

Treatments need to be flexible, efficient, inexpensive, and acceptable to the participants in a wide variety of clinical and community settings. For a disorder with a 20 percent lifetime prevalence, treatments are needed in many different languages and in many different settings.

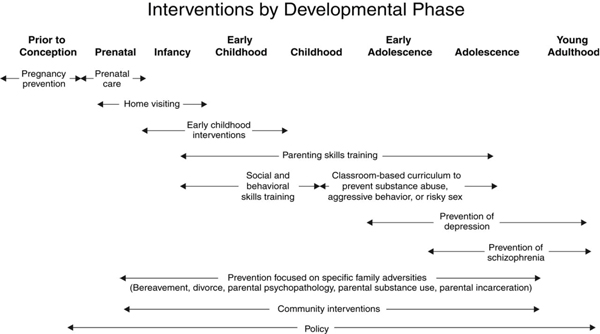

A wide variety of prevention options exist across the life span (Figure 4-1). In addition, three areas need attention across the life span: tools to cope with specific family adversities, community interventions, and policy. Considerable promise surrounds several different strategies, including preventing or improving depression in parents, targeting the vulnerabilities or strengths of depressed parents, improving parent-child relationships, and using a two-generation approach. In addition, depression is overrepresented in high-risk populations, so programs for those populations need to be augmented with depression prevention.

The key challenge now is to take effective interventions to scale through community, state, federal, and international initiatives. Families

FIGURE 4-1 Many opportunities for preventive interventions differ by developmental phase.

SOURCE: National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2009b).

need to be engaged in multiple ways, and systematic barriers need to be removed to include prevention in interventions. One strategy would be to gather data about children when assessing parents. Another would be to embed strategies to help parents who are struggling in existing programs like Head Start, with prevention services delivered to the family rather than just the individual.

More than three-quarters of the major mental illnesses in adulthood have their origins in childhood, so prevention needs to begin early in life. “If we have a choice, we should intervene most intensively in the first five years of life, because that is when, if things go well, it sets the stage for success later on, and if they go badly, it costs a great deal more to remedy them,” Beardslee said. Successful prevention is inherently interdisciplinary. It has mental, emotional, behavioral, and physical dimensions. Prevention is very different from treatment. It requires a new paradigm about what a child needs one, three, and five years in the future. Coordinated community-level systems are needed to support young people before the age of highest risk, at the age when prevention is likely to have the largest impact.

STUDYING SUBSTANCE-ABUSING FATHERS: CAN EVOLUTIONARY CONCEPTS HELP?

Can concepts adopted from evolutionary theory explain the reproductive history of substance-abusing men who are assumed to be at risk for socially irresponsible fathering? Thomas McMahon, associate professor of psychiatry and child study at the Yale University School of Medicine, explored this question using data from a study of such men in New Haven, Connecticut.

Following the passage of the Welfare Reform Act of 1996 and the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997, the federal government convened a working group on the status of fatherhood. The group highlighted the pressing need for more information about the ways that men go about producing and parenting children, particularly men who were likely to be affected by changes in federal policy and programs.

McMahon has been interested in whether life history theory can explain individual differences in the reproductive behavior of humans. Life history theory is a broad conceptual framework borrowed from evolutionary biology that focuses on the way organisms balance or negotiate competing life functions. Life history scholars distinguish between somatic effort, which represents the energy that the organism devotes to growth and survival as an individual, and reproductive effort, which is the effort that the organism devotes to supporting the growth and survival of the species. At the r end of what life history theorists term the r/K continuum, reproductive

effort takes precedence over somatic effort. (The terms r and K come from a standard equation used to describe population dynamics.) Species mature very quickly, produce large litters of offspring relatively few times over the course of a life span, and devote less energy to parenting or to caretaking, in part because the organism has a shorter life span and a high risk of early mortality in the ecological niche in which it lives. In the world of mammals, mice and rabbits tend to be at this end of the continuum. At the K end of the continuum, somatic effort takes precedence over reproductive effort. Species mature very slowly, produce smaller litters of offspring over a more extended period, and devote more energy to caretaking, in part because they have a longer life span and they live in environments in which risk of early mortality is more limited. Elephants, whales, and humans tend to fall at this end of the continuum.

This theory was originally developed to highlight differences across species, but some have extended it to look at the differences within species. In humans, it has been used to account for individual differences in reproductive behavior. When children live in unstable, stressful early family environments in which caretaking is inconsistent or insensitive and family resources are limited, they may develop insecure attachments, a negative view of the future, and a short-term orientation to life. As these children enter adolescence, life history theorists argue, they are at risk of pursuing a short-term or low-K approach to reproduction characterized by early puberty, early first sexual intercourse, less stable sexual partnerships, early birth of a first child, more children spaced closer together conceived with more partners, and less investment in parenting. This approach to reproduction is adaptive for individuals given the ecological niche that they had to negotiate as a child. However, social policy labels these actions as socially irresponsible, because they typically leave children without the skills or resources needed to support their positive development in a modern technologically oriented culture.

In contrast, when children live in stable, supportive early family environments characterized by consistent, sensitive caretaking and adequate family resources, they typically develop secure attachments, a positive view of the future, and a longer term orientation to life. As they enter adolescence, these children are thought to be more likely to pursue what life history scholars call a high-K or long-term approach to reproduction, characterized by later onset of puberty, later first sexual intercourse, stable sexual partnerships, and later first birth of a child. They typically have fewer children spaced farther apart, conceived with the same sexual partner, with more investment in parenting. Again, from the perspective of the individual, this is generally viewed as adaptive, given the ecological niche negotiated as a child. Society labels this behavior as socially responsible.

McMahon and his colleagues studied 106 opiate-dependent fathers

enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment and 118 demographically matched fathers living in the same community with no history of alcohol or drug abuse. The men were an average of about 40 years of age and included white, black, and Hispanic men. As a group they had an average of about 13 years of education.

The researchers found that there was no significant difference between the substance-abusing men and the control group in whether or not the parents of these men were legally married at some point during their childhood. They also found that there was no significant difference in whether or not the men had lived with their biological father at some point before their 18th birthday. However, the drug-abusing fathers were more likely to have experienced the separation of their parents sometime before their 18th birthday.

There was no difference in self-report of the quality of early relationships with mothers, but the drug-abusing fathers were less likely to report that they had ever been close with their biological father during childhood. The drug-abusing fathers also reported more exposure to emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and emotional and physical neglect as a child.

The two groups had significant differences in the pattern of legal marriage. The drug-abusing fathers were more likely to never have been married, less likely to have been married once, and more likely to have been married three times. There were also significant differences in patterns of cohabitation. The drug-abusing fathers were less likely to have never cohabitated or only have been involved in one live-in relationship. They were more likely to have been involved in three, four, five, or more live-in relationships.

The drug-abusing fathers were more likely to have had a first child when they were younger than 25. They were also less likely to have one or two biological children, and they were more likely to have had three, four, five, or more biological children.

Finally, the drug-abusing fathers were less likely to have had children with only one sexual partner. They were more likely to have had children with two, three, four, or more different women.

McMahon concluded that modern evolutionary theory may help explain high-risk fathering in the context of chronic substance abuse. It provides a framework in which to examine both substance abuse and the family careers of men who are assumed to be at risk of behaving in a socially irresponsible way. It moves beyond looking at parenting behavior to the ways that men produce and parent children over the course of their lifetimes. In this way, it allows for the integration of both biological and psychosocial influences.

Both genetic predispositions and early developmental experiences may play a role in choices about reproduction. Personality and attachment style

may be mediating influences, and contextual factors, particularly incarceration, may be an important moderator in this process.

This research has challenges, McMahon acknowledged. Many negative stereotypes surround this population of men, even though they are more involved with their children than most people assume, despite common stereotypes.

Response burden on participants has been a problem. When working with special populations, there are challenges measuring the three multidimensional constructs: (1) substance abuse, (2) family process, and (3) child development. There are also particular challenges associated in reliably measuring these constructs with subjects who may have limited verbal or reading skills.

The construct of reproductive strategies is another area of potential interest when examining family process, but it too must be clearly defined and there must be a strategy to measure it. One question is, “Who speaks for Dad?” McMahon and his colleagues have insisted that men be the primary informants about their reproductive history, but that approach has generated skepticism about the accuracy of their responses. Some researchers remain skeptical about whether men, especially socially and economically disenfranchised populations of men like substance-abusing men, can reliably provide information about their reproduction and parenting of children because of gender bias among researchers who assume mothers are better informants about family life.

In addition, there has been difficulty recruiting mothers and children to serve as collateral informants, which is a standard practice in family research. Requiring collateral informants when studying drug-abusing fathers may skew samples toward men pursuing a more socially responsible approach to reproduction, when family relations have been preserved despite the presence of ongoing drug abuse. This approach may omit cases where men are estranged from their children and the mother of their children because of the impact their substance abuse has had on family relationships. This is a particularly important challenge, because when a researcher is required to secure a collateral informant in order for a father to enroll in a study, the sample may be skewed toward the inclusion of fathers with less disruption of family and the exclusion of those fathers with disrupted relationships, who may be the central focus of the study.

McMahon also speculated that there might be two clusters of fathers in this population being studied. One cluster would be pursuing a socially responsible approach to reproduction that has been disrupted or derailed by substance abuse. A smaller cluster of fathers may be pursuing a short-term, socially irresponsible approach to reproduction that evolved concurrently with the substance abuse and is undoubtedly associated with other social problems.

These results have implications for interventions, said McMahon. In particular, if the two-cluster approach is valid, interventions may need to be adapted to the needs of men with different reproductive strategies.

DISCUSSION

In response to a question about how he might use additional funding for his research, Thomas McMahon indicated that he would like to see qualitative measures integrated into clinical trials research. He also would try to integrate measures of genetic risk into his research. “The behavioral genetics literature suggests that . . . somewhere between 40 and 60 percent of most markers of reproductive history have some kind of a genetic component. The molecular community has begun to show that there are some links between specific genes and different dimensions of sexual and parenting behavior.” No one gene will ever account for a complex behavior, he acknowledged, but multidimensional measures of genetic risk may be possible for some of the reproductive behaviors labeled socially irresponsible.