Oral Health and Overall

Health and Well-Being

A number of factors influence oral health status and may act as obstacles to improving the oral health of the nation. Patients and health care professionals need to understand the importance of oral health, especially its connection to overall health, and apply that knowledge in practice. In addition, patients need to have the knowledge, understanding, ability, and means to access oral health care, and professionals must be available to provide care. Oral health may also be affected by several social determinants of health such as race, income, living conditions, and working conditions.

This chapter presents an overview of the inextricable link between oral health and overall health and well-being, as well as the many factors that can affect oral health improvement. First, the connection between oral health and overall health, including the implications of poor oral health, is briefly discussed. Next, the overall health status of the American population is reviewed, and the oral health status and utilization patterns of various vulnerable and underserved populations are considered. The chapter continues with the examination of preventive oral health interventions for many oral diseases. Finally, the chapter concludes with a discussion of basic health literacy issues (including oral health literacy), especially how they affect the ability of individuals, communities, and practitioners to improve oral health status. The specific roles of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in health literacy and prevention are discussed in Chapter 4.

THE LINK BETWEEN ORAL HEALTH AND OVERALL HEALTH

For people suffering from dental, oral, or craniofacial pain, the link between oral health and general well-being is beyond dispute. However, for policy makers, payers, and health care professionals, a chasm dividing the two has developed over time and continues to exist today. In effect, the oral health care field has remained separated from general health care (e.g., medicine, pharmacy, nursing, allied health professions). Recently, however, researchers and others have placed a greater emphasis on establishing and clarifying the oral-systemic linkages.

The surgeon general’s report Oral Health in America made it clear that oral health care is broader than dental care and that a healthy mouth is more than just healthy teeth (see Box 2-1). The report described the mouth as a mirror of health and disease occurring in the rest of the body, in part because a thorough oral examination can detect signs of numerous general health problems, such as nutritional deficiencies and systemic diseases, including microbial infections, immune disorders, injuries, and some cancers (HHS, 2000b). Oral lesions are often the first manifestation of HIV infection and may be used to predict progression from HIV to AIDS (Coogin et al., 2005). Sexually transmitted HP-16 virus has been established as the cause of a number of vaginal as well as oropharyngeal cancers (Marur et al., 2010; Shaw and Robinson, 2010). Dry mouth (xerostomia) is an early symptom of Sjogren’s syndrome, one of the most common autoimmune disorders (Al-Hashimi, 2001), and is also a side effect for a large number

BOX 2-1

Dental, Oral, and Craniofacial

The word oral refers to the mouth. The mouth includes not only the teeth and the gums (gingiva) and their supporting tissues but also the hard and soft palate, the mucosal lining of the mouth and throat, the tongue, the lips, the salivary glands, the chewing muscles, and the upper and lower jaws. Equally important are the branches of the nervous, immune, and vascular systems that animate, protect, and nourish the oral tissues, as well as provide connections to the brain and the rest of the body. The genetic patterning of development in utero further reveals the intimate relationship of the oral tissues to the developing brain and to the tissues of the face and head that surround the mouth, structures whose location is captured in the word craniofacial.

SOURCE: HHS, 2000b.

of prescribed medications (Nabi et al., 2006; Uher et al., 2009; Weinberger et al., 2010).

Further, there is mounting evidence that oral health complications not only reflect general health conditions but also exacerbate them. Infections that begin in the mouth can travel throughout the body. For example, periodontal bacteria have been found in samples removed from brain abscesses (Silva, 2004), pulmonary tissue (Suzuki and Delisle, 1984), and cardiovascular tissue (Haraszthy et al., 2000). Periodontal disease may be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes (Offenbacher et al., 2006; Scannapieco et al., 2003b; Tarannum and Faizuddin, 2007; Vergnes and Sixou, 2007), respiratory disease (Scannapieco and Ho, 2001), cardiovascular disease (Blaizot et al., 2009; Janket et al., 2003; Paraskevas, 2008; Scannapieco et al., 2003a; Slavkin and Baum, 2000), coronary heart disease (Bahekar et al., 2007), and diabetes (Chávarry et al., 2009; Löe, 1993; Taylor, 2001; Teeuw et al., 2010). However, the relationship between periodontal disease and these systemic diseases is not well understood, and there is conflicting evidence about whether periodontal treatment affects outcomes for these systemic conditions (Beck et al., 2008; Fogacci et al., 2011; Jeffcoat et al., 2003; Lopez et al., 2002, 2005; Macones et al., 2010; Michalowicz et al., 2006; Newnham et al., 2009; Offenbacher et al., 2006, 2009; Paraskevas et al., 2008; Polyzos et al., 2009, 2010; Sadatmansouri et al., 2006; Simpson et al., 2010; Tarannum and Faizuddin, 2007; Teeuw et al., 2010; Uppal et al., 2010).

Although there is a wide range of diseases and conditions that manifest themselves in or near the oral cavity itself, discussions of oral health tend to focus on the diagnosis and treatment of two types of diseases and their sequelae: dental caries and periodontal diseases. The most common of those diseases, dental caries, is a common chronic disease in the United States (Dye et al., 2007) and among the most common diseases in the world (WHO, 2010e). As mentioned previously, periodontal disease has been associated with numerous systemic diseases throughout the body from heart disease to diabetes (Bahekar et al., 2007; Chávarry et al., 2009). There is some degree of tragedy in this situation because both dental caries and periodontal disease are highly preventable.

Dental caries was described in the surgeon general’s report as “the single most common chronic childhood disease” (HHS, 2000b). Most people remain unaware that dental caries is caused by a bacterial infection (e.g., Streptococcus mutans) that is often passed from person to person (e.g., from mother to child). Aside from dental health implications, nontreatment of dental caries may be associated with several types of morbidity (both individual and societal), including loss of days from school (Gift et al., 1992, 1993), inappropriate use of emergency departments (Cohen et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2010), orofacial pain (Nomura et al., 2004; Traebert et

al., 2005), and inability for military forces to deploy (Bray, 2006). In fact, while the death of Deamonte Driver made headlines and sparked a national debate about the importance of oral health care (Norris, 2007; Otto, 2007), there have been other similar cases in recent times (Casamassimo et al., 2009; Jackson, 2007). In spite of decades of knowledge of how to prevent dental caries, this disease remains a significant problem for all age groups.

Evidence on how well the current oral health system is performing can be found in the mouths of the American people. And while evidence suggests that oral health has been improving in most of the U.S. population, many sub-groups are not faring as well (Dye et al., 2007).

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

One of the most important functions HHS has performed over time has been monitoring the oral health status of the nation. The department has conducted a number of national data collection efforts through the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as other agencies within the department. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is the main source for oral health information in the United States; data are collected from a representative sample of the civilian U.S. population through interviews and clinical examinations.

In April 2007, the National Center for Health Statistics released a comprehensive assessment of U.S. oral health status (Dye et al., 2007). Using data provided by two iterations of the NHANES (NHANES III, 1988–1994 and NHANES 1999–2004), the assessment concluded that most Americans experienced improvements in their oral health over the two time periods (Dye et al., 2007). Specifically, the report noted that among older adults, edentulism (complete tooth loss) and periodontitis (gum disease) had declined. Among adults, the CDC observed improvements in the prevalence of dental caries, tooth retention, and periodontal health. For adolescents and youths, dental caries decreased, while dental sealants (thin plastic coatings applied to the grooves on the chewing surfaces of the back teeth to protect them from dental caries) became more prevalent. Among poor Mexican-American children ages 6–11, untreated dental caries decreased from 51 to 42 percent (Dye et al., 2010). The proportion of adolescents age 12–19 with caries in their permanent dentition decreased (Edelstein and Chinn, 2009). More children have received at least one dental sealant on a permanent tooth; the prevalence increased from 22 to 30 percent among children ages 6–11 and from 18 to 38 percent in adolescents ages 12–19 (Dye et al.,

2007). Encouragingly, the increase was consistent among all racial and ethnic groups, although non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American children and adolescents continue to have a lower prevalence of sealants than do whites, and poor children receive fewer dental sealants than those who live above 200 percent of the federal poverty line (Dye et al., 2007).

While the data from the NHANES surveys showed improvements in oral health status across two intervals of time, the most current information on American oral health status was not especially favorable. For example, the latter survey found that more than a quarter of adults ages 20–64 and nearly one-fifth of respondents over age 65 were experiencing untreated dental caries at the time of their examination (Dye et al., 2007). Further, caries prevalence among preschool children increased between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004 (Dye et al., 2007). Based on the NHANES results, Table 2-1 provides an overview of the U.S. population’s oral health status during the 1999–2004 time period. The percentage of persons with caries experience increases with age, in part because once cavitated, this is a nonreversible disease measured by active and treated disease. While a fifth of children 6–11 years of age have had caries, this proportion increases to more than half of children 12 to 19 years of age and to 90-plus percent of adults 20 years and over. Socioeconomic status, measured by poverty status in this case, is a strong determinant of oral health (Vargas et al., 1998). In every age group, persons in the lower-income group were more likely to have had caries experience and more than twice as likely to have untreated dental caries compared with their higher-income counterparts. Among persons age 65 and over, edentulism is more frequent among those living below the poverty level than among those living at twice the poverty level (Dye et al., 2007).

In addition, a significant proportion of the population continues to suffer from periodontal disease. According to the most recent NHANES survey, at least 8.5 percent of adults (ages 20–64) and 17.2 percent of older adults (age 65 and older) in the United States suffer from periodontal disease (NIDCR, 2011a,b), and in fact, the periodontal examination used in NHANES may have understated the true incidence of periodontal disease by 50 percent or more (Eke et al., 2010).

Healthy People

Since 1980, HHS has used the Healthy People process to set the country’s health-promotion and disease-prevention agenda (Koh, 2010). Healthy People is a set of health objectives for the nation consisting of overarching goals for improving the overall health of all Americans and more specific objectives in a variety of focus areas, including oral health. Every 10 years, HHS evaluates the progress that has been made on Healthy People goals

TABLE 2-1

Prevalence of Caries Experience and Untreated Caries by Age and Poverty Status (1999–2004)

| Population Characteristics | Caries Prevalence | |||

| Caries Experience | Untreated Caries | |||

| Age and Dentition | Percentage | Percentage | ||

| 2-11 primary teeth | Total 2- to ll-year olds | 42.2 | 22.9 | |

| 2-5 years | 27.9 | 20.5 | ||

| 6-11 years | 51.2 | 24.5 | ||

| Poverty | <100% | 54.3 | 32.5 | |

| 100-200% | 48.8 | 28.4 | ||

| >200% | 32.3 | 15.0 | ||

| 6-11 permanent teeth | Total 6- to 11-year olds | 21.1 | 7.7 | |

| Poverty | <100% | 28.3 | 11.8 | |

| 100-200% | 24.1 | 11.9 | ||

| >200% | 16.3 | 3.6 | ||

| 12-19 permanent teeth | Total 12- to 19-year olds | 59.1 | 19.6 | |

| Poverty | <100% | 65.6 | 27.1 | |

| 100-200% | 64.4 | 27.0 | ||

| >200% | 54.0 | 12.9 | ||

| 20-64 permanent teeth | Total 20- to 64-year olds | 91.6 | 25.5 | |

| 20-34 | 85.6 | 27.9 | ||

| 35-49 | 94.3 | 25.6 | ||

| 50-64 | 95.6 | 22.1 | ||

| Poverty | <100% | 88.7 | 43.9 | |

| 100-200% | 88.9 | 39.3 | ||

| >200% | 93.1 | 18.0 | ||

| 65+ permanent teeth | Total 65+ | 93.0 | 18.2 | |

| Poverty | <100% | 83.5 | 33.2 | |

| 100-200% | 90.9 | 23.8 | ||

| >200% | 95.5 | 14.2 | ||

SOURCE: Dye et al., 2007.

and objectives, develops new goals and objectives, and sets new benchmarks for progress. The objectives are drafted by relevant HHS agencies, with extensive input from external stakeholders and the public. The oral health objectives are developed by four co-lead agencies—the CDC, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Indian Health Service, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—with input from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, the Office of Minority Health, the Office on Women’s Health, and the National Center for Health Statistics, as well as comments from dental professional organizations, including state and local dental directors (Dye, 2010). (See Chapter 4 for more on the history of Healthy People as well as a description of Healthy People 2020 goals and objectives.)

Progress on the Healthy People 2010 goals was mixed (Koh, 2010; Sondik et al., 2010; Tomar and Reeves, 2009). At the midcourse review in 2006, no oral health objectives had met or exceeded their targets (HHS, 2006). Encouragingly, however, progress was made in a number of categories, including decreasing caries among adolescents (although not among younger children), increasing the proportion of children with dental sealants, increasing the proportion of adults with no permanent tooth loss, and increasing the proportion of the population with access to community water fluoridation (HHS, 2006; Tomar and Reeves, 2009). In contrast, several objectives moved away from their targets. For example, the proportion of children age 2 to 4 years with dental caries increased from 18 to 22 percent, and the proportion of untreated dental caries in this population increased from 16 to 17 percent (HHS, 2006). In addition, the number of oral and pharyngeal cancers detected at an early stage decreased.

Oral Health Status: Beyond the Teeth

Oral health is more than healthy teeth, and oral diseases and disorders are more than caries and periodontal disease. Oral diseases and disorders can be either acute (e.g., broken tooth) or chronic (e.g., caries) and have a number of different causes, including inheritance (e.g., cleft lip and palate), infection (e.g., caries), neoplasia (e.g., oral, nasal, and pharyngeal cancers), and neuromuscular (e.g., temporomandibular joint disorder). Although caries and periodontal disease are the most commonly discussed oral diseases, other oral diseases also have a significant burden. Between 1999 and 2001, the annual prevalence of cleft lip in the United States was approximately 1 in 1,000 live births (NIDCR, 2010). The overall incidence of head and neck cancers is falling due to declining use of cigarettes and other tobacco products; however, an increasing number of younger women without the typical risk factors (tobacco and alcohol use) have been diagnosed with oral cancers, causing speculation about the relationship between human papil-

loma virus and oral cancer (D’Souza et al., 2007; Mork et al., 2001; Sturgis and Cinciripini, 2007). In 2010, there were more than 36,000 new cases of oral and pharyngeal cancer (Altekruse et al., 2010). Although early-stage oral cancers are treatable, the mortality rate is relatively high because most oral cancers are diagnosed at a later stage (HHS, 2000b). This problem is particularly acute for African Americans, who are more likely to be diagnosed at a late stage and who have a much lower 5-year survival rate than whites do (about 42 percent for African Americans compared to about 63 percent for whites) (Altekruse et al., 2010).

ORAL HEALTH STATUS AND ORAL HEALTH CARE UTILIZATION BY SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

While some data show improvements in the U.S. oral health status overall, underserved and vulnerable populations continue to suffer disparities in both their disease burden and access to needed services. Dental caries remains a significant problem in certain populations such as poor children and racial and ethnic minorities of all ages (Dye, 2010; Dye et al., 2007). In addition, limited and uneven use of oral health care services contributes to both poor oral health and disparities in oral health. More than half of the population (56 percent) did not visit a dentist in 2004 (Manski and Brown, 2007), and in 2007, 5.5 percent of the population reported being unable to get or delaying needed dental care, higher than the percentage that reported being unable to get or delaying needed medical care or prescription drugs (Chevarley, 2010). In this section, the particular issues of some underserved populations are highlighted. The specific challenges of these populations and others are being examined more in depth by the IOM Committee on Oral Health Access to Services.

Age Groups

Dental disease is also a problem across the age spectrum. In this section, special challenges for children, adolescents, and older adults are highlighted.

Children

Over the decades, many different sources have noted the burden of dental disease on children. The surgeon general’s report identified dental caries as “the single most common chronic childhood disease—five times more common than asthma and seven times more common than hay fever” (HHS, 2000b). Over 27 percent of children ages 2 to 5 have early childhood caries (defined as caries in children ages 1 to 5 years old), and more

than 50 percent of children ages 6 to 11 have caries in their primary teeth (Dye et al., 2007; Ismail and Sohn, 1999). More than 20 percent of those caries are untreated (Dye et al., 2007). The lack of adequate dental treatment may affect children’s speech, nutrition, growth and function, social development, and quality of life (HHS, 2000b). For school-age children in particular, oral disease can impose restrictions in their daily activities; in excess of 51 million school hours are lost each year due to dental-related illness (HHS, 2000b). In addition, 14 percent of children 6–12 years old have had toothache severe enough during the past six months to have complained to their parents, and many others may have suffered silently with the same symptoms (Lewis and Stout, 2010).

Adolescents

Adolescents, generally those age 10–19 (IOM, 2009), have risk factors for dental caries similar to those for other age groups, but adolescents’ risk for oral and perioral injury is especially exacerbated by behaviors such as the use of alcohol and illicit drugs, driving without a seat belt, cycling without a helmet, engaging in contact sports without a mouth guard, and using firearms (IOM, 2009). Other concerns among adolescent populations (that may be similar to those of other age groups) include damage caused by the use of all forms of tobacco, erosion of teeth and damage to soft tissues caused by eating disorders, oral manifestations of sexually transmitted infections (e.g., soft tissue lesions) as a result of oral sex, and increased risk of periodontal disease during pregnancy.

Adults

Adults ages 20 to 64 have similar risk factors for oral disease as other age groups, although because oral disease accumulates with age, adults generally have more oral disease than do their younger cohorts. In addition, adults may have difficulty obtaining dental insurance, because many states offer limited or no dental benefits to adults through Medicaid (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2011). In 2007, 5 percent of adults were covered by public dental insurance, an additional 65.5 percent had private coverage, and 35.5 percent lacked dental insurance altogether (Manski and Brown, 2010).

Older Adults

Both the prevalence of periodontal disease and the percentage of teeth with caries increase as the population ages (Dye et al., 2007; Vargas et al., 2001). Older adults often have chronic diseases that may exacerbate their oral health, and vice versa. Older adults are more likely to have serious

medical issues and functional limitations, which can deter them from seeking dental care (Dolan et al., 1998; Kiyak and Reichmuth, 2005). Older adults who spend more on medication and medical visits are less likely to use dental services (Kuthy et al., 1996). Moreover, dental insurance is generally linked to employment, and upon retirement, most older adults lose their dental insurance (Manski et al., 2010). Despite these challenges, the oral health of older adults is improving: between NHANES III and NHANES 1999–2004, the prevalence of caries, periodontal disease, and edentulism among older adults all decreased (Dye et al., 2007).

While federal law requires long-term care facilities that receive Medicare or Medicaid funding to provide access to dental care, only 80 percent of facilities report doing so (Dolan et al., 2005). Even when dental care is available, many residents do not regularly receive dental care, and many oral health problems go undetected (Dolan et al., 2005). Only 19 percent of dentists report providing treatment in long-term care facilities in the past, and only 37 percent showed interest in doing so in the future (Dolan et al., 2005). In the absence of dentists, nursing home staff must identify residents’ oral health needs, but nurses (as well as many other health professionals) are not adequately trained to identify or treat many oral health issues (Dolan et al., 2005; IOM, 2008).

People with Special Health Care Needs

It appears that people with special health care needs1 have poorer oral health than the general population has (Anders and Davis, 2010; Owens et al., 2006). Most, though not all, studies indicate that the overall prevalence of caries in people with special needs is either the same as the general population or slightly lower (Anders and Davis, 2010; López Pérez et al., 2002; Seirawan et al., 2008; Tiller et al., 2001). But, available data indicate that people with special needs suffer disproportionately from periodontal disease and edentulism, have more untreated caries, have poorer oral hygiene, and receive less care than the general population does (Anders and Davis, 2010; Armour et al., 2008; Havercamp et al., 2004; Owens et al., 2006). However, high-quality data on the oral health of people with special needs in the United States is scarce (Anders and Davis, 2010). People with special health care needs are a difficult population to reach, in part because of their diversity, and also because they are geographically dispersed. Moreover, it is also difficult to analyze national data on this population because their numbers are not large enough to produce reliable statistics. Many of the

![]()

1 For the purpose of this report, people with special health care needs are people who have difficulty accessing oral health care due to complicated medical, physical, or psychological conditions (Glassman and Subar, 2008).

available studies of people with special health care needs were conducted with populations that are not representative of the special needs community as a whole (Feldman et al., 1997; Owens et al., 2006; Reid et al., 2003).

Disparities in oral health for people with special needs are due to a variety of reasons. People with special needs often take medications that cause a reduced saliva flow, which promotes caries and periodontal disease (HHS, 2000b). Additionally, people with special needs often have impaired dexterity and thus rely on others for oral hygiene (Shaw et al., 1989). They also face systematic barriers to oral health care such as transportation barriers (especially for those with physical disabilities), cost, and health professionals that are not trained to work with special needs patients or dental offices that are not physically suited for them (Glassman and Subar, 2008; Glassman et al., 2005; Stiefel, 2002; Yuen et al., 2010).

Poor Populations

Poor children are more likely to have untreated dental caries and less likely to receive sealants than nonpoor children, despite having almost universal access to dental insurance through Medicaid (Dye et al., 2007; HHS, 2000b). Poor children and adults receive fewer dental services than does the population as a whole (Dye et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2007; Stanton and Rutherford, 2003). Encouragingly, however, a recent analysis of NHANES data indicated that the largest increase in dental sealant use occurred among poor children, although they continue to lag behind higher-income children (Dye and Thornton-Evans, 2010). The increase among poor children may be due to school-based sealant programs, which in 17 states reach children in 25 percent or more of schools serving low-income families (Pew Center on the States, 2010). The likelihood of visiting a dentist decreases with decreasing income, and people from poor families are less likely to have visited a dentist within the previous year and less likely to have a preventive dental visit (Manski and Brown, 2007; Stanton and Rutherford, 2003).

Pregnant Women and Mothers

The oral health care of women is important for the health of the women as well as for the effects it has on their children. The oral health status of children has been linked both with the oral health status of their mother as well as their mother’s educational level (Fisher-Owens et al., 2007; Ramos-Gomez et al., 2002; Weintraub, 2007; Weintraub et al., 2010). For some populations of children, evidence suggests that children’s use of oral health care services is higher when their mothers have regular access to care (Grembowski et al., 2008; Isong et al., 2010). Arguably, the oral health care of children begins during pregnancy. For example, use of folic acid supple-

ments during pregnancy may reduce the risk for isolated cleft lip (with or without cleft palate) by about one-third (Wilcox et al., 2007). In addition, periodontal disease in pregnant women has been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm low birth weight (Offenbacher et al., 2006; Scannapieco et al., 2003b; Tarannum and Faizuddin, 2007; Vergnes and Sixou, 2007), and use of preventive dental care during pregnancy is associated with lower incidence of adverse birth outcomes (Albert et al., 2011). After birth, the bacteria responsible for causing dental caries in children, mutans streptococci, appears to be transmissible from caregivers, especially mothers, to children (Berkowitz, 2006; Douglass et al., 2008; Li and Caufield, 1995; Slavkin, 1997).

Obstetricians and gynecologists need to be aware of how oral health has a particular interaction with the overall health of pregnant women. For example, hormonal changes during pregnancy put pregnant women at higher risk of developing oral diseases, most commonly gingivitis, which affects 30–75 percent of pregnant women (Silk et al., 2008; Steinberg et al., 2008). Oral health services for pregnant women and mothers may include education and counseling about how their own oral health relates to their children’s oral health, as well as how to prevent dental caries in their young children. Although oral health care for pregnant women is safe and effective, less than half of women receive oral care or counseling during pregnancy (ACOG, 2004; CDA, 2010; Gaffield et al., 2001; Hwang et al., 2010; Michalowicz et al., 2008; New York State Department of Health, 2006; Newnham et al., 2009). In addition, there are significant racial and ethnic disparities in the oral health care of pregnant women (Hwang et al., 2010). The reasons for low use of oral care during pregnancy are similar to those for other populations, such as cost and low reimbursement for dentists, but reasons also include incorrect knowledge by both professionals and patients about the safety of dental care for pregnant women (Al Habashneh et al., 2005; Detman et al., 2010; Huebner et al., 2009; Hughes, 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Russell and Mayberry, 2008). In addition, while health care professionals may be aware of the importance of oral health care during pregnancy, they often still do not address it with their patients (Morgan et al., 2009).

Racial and Ethnic Minorities

Hispanics and African Americans have poorer oral health than whites have (Dietrich et al., 2008; Dye et al., 2007; Vargas and Ronzio, 2006). These disparities exist independently of income level, education, dental insurance status, and attitude toward preventive dental care, and they persist throughout the life cycle, from childhood through old age (Dietrich et al., 2008; Dye et al., 2007; Kiyak and Reichmuth, 2005). Minority children are

more likely to have dental caries than are white children, and their decay is more severe (Vargas and Ronzio, 2006). American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN) have poorer oral health than does the overall U.S. population throughout the life cycle (IHS, 2002; Jones et al., 2000). The prevalence of tooth decay in AI/AN children ages 2 to 5, for example, is nearly three times the U.S. average, and more than two-thirds of AI/AN children ages 2 to 5 have untreated dental caries (Dye et al., 2007; IHS, 2002).

Hispanics and African Americans receive fewer dental services compared to white populations. They are less likely to report any dental visit in the past year, either for preventive, restorative, or emergency care (Dietrich et al., 2008; Manski and Brown, 2007; Manski and Magder, 1998). When migrant and seasonal farmworkers were asked which health care service would benefit them the most, the most common response was dental services, ahead of pediatric care, transportation, and interpretation, among other services (Anthony et al., 2008).

Assurance of equal access to dental care can markedly reduce some oral health disparities. A study of the oral health of military personnel found “the disparities between black and white adults in untreated caries and recent dental visits that are seen in the U.S. civilian population were absent among military personnel. Racial disparities in missing teeth persisted among military personnel, though they were much smaller than those seen in their civilian counterparts” (Hyman et al., 2006).

Rural Populations

About 17 percent of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, and this is expected to increase dramatically with the aging of the baby boom population (Cromartie and Nelson, 2009; USDA, 2009). In general, rural residents have significantly poorer oral health than urban residents have throughout the life cycle (Vargas et al., 2002, 2003a,b,c). Residents of rural areas are less likely than urban residents to have visited a dentist in the past year and more likely to have unmet dental needs (Vargas et al., 2003a,b,c). A number of factors contribute to these problems. The supply of dentists in rural counties is less than half that of urban counties, with 29 dentists per 100,000 residents in the most rural counties compared to 61–62 dentists per 100,000 residents in large metropolitan areas (Eberhardt et al., 2001). Residents of rural areas must travel further than urban residents do to reach dental care (Probst et al., 2007). In addition, a smaller proportion of rural residents have dental insurance, which is predictive of oral health care use (DeVoe et al., 2003; Lewis et al., 2007). Rural populations are also less likely to have access to fluoridated community water supplies and have higher rates of tobacco use (Skillman et al., 2010), both of which are directly related to the development of oral diseases.

The World Health Organization defines oral health as “a state of being free from chronic mouth and facial pain, oral and throat cancer, oral sores, birth defects such as cleft lip and palate, periodontal (gum) disease, tooth decay and tooth loss, and other diseases and disorders that affect the oral cavity. Risk factors for oral diseases include unhealthy diet, tobacco use, harmful alcohol use, and poor oral hygiene” (WHO, 2010a).

The term prevention has been applied in a number of ways. In oral health care, the term can refer to brushing with fluoride toothpaste, flossing, oral health screenings by a health care professional, and the professional application of fluorides, but it might also be applied to drilling and filling a tooth to prevent loss of function. So the term prevention can be applied at various stages of the disease process. For example, a 2005 IOM report on childhood obesity adopted the public health definition of prevention, saying that

With regard to obesity, primary prevention represents avoiding the occurrence of obesity in a population; secondary prevention represents early detection of disease through screening with the purpose of limiting its occurrence; and tertiary prevention involves preventing the sequelae of obesity in childhood and adulthood. (IOM, 2005)

This definition has been used regularly in the context of oral health (Dunning, 1986; HHS, 2000b).

In this chapter, the committee will focus on primary prevention. This is fitting, given the highly preventable nature of oral diseases, including dental caries and periodontal disease. The objective of oral health promotion and disease prevention is to promote the optimal state of the mouth and the normal functioning of the organs of the mouth without evidence of disease. While secondary and tertiary prevention will not be discussed extensively in this report, the committee recognizes that they are important in overall oral health. For example, secondary prevention may be considered through improving the education and training of primary health care providers to look for early signs of oral disease during routine health examinations (discussed more in Chapter 3), and tertiary prevention may include interventions by oral health care providers to manage oral diseases once present, including the prevention of further decay and infection.

Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease: The Disease Process

The basic etiology of dental caries and periodontal disease has been understood for many years. Teeth are normally covered in biofilms (also known as dental plaque) that consist of complex microbial communi-

ties (Marsh, 2006). The composition of this dental plaque is exquisitely sensitive to its environment, and both diseases result from alterations in the ecology in ways that allow virulent species to become predominant (Marsh, 2006). Unlike other bacterial pathologies such as E. coli and salmonella, in which the bacterial pathogens are exogenous, in the case of oral disease, the bacteria involved are indigenous to the mouth. This habitat is significantly influenced by saliva, food, fluoride, toothbrushing and dental flossing, and when present, to smoke, tobacco, alcohol, and other noxious agents.

For example, excessive exposure to sugar can lead to dental caries as the bacterial composition of the plaque changes from a healthy state to one that is overly acidic and consequently pathologic (cariogenic). At that point, the predominant bacteria in the biofilm on the teeth begin to transition to species that are acidogenic and aciduric (primarily S. mutans), and the biofilm becomes cariogenic (Marsh, 2006). A similar transition occurs in the biofilm associated with periodontal disease (Pihlstrom et al., 2005). In susceptible individuals, when the biofilm remains undisturbed by failing to maintain adequate oral hygiene, the plaque transitions from one characterized by gram-positive aerobic species to one that is composed of gram-negative anaerobic species (Marsh, 2003). This ecological shift in the biofilm leads to periodontal disease, a condition that eventually destroys the tooth’s attachment to the gums and leads to tooth loss.

Effective Interventions

Many oral diseases can be prevented through a combination of steps taken at home, in the dental office or other care locations, or on a community-wide basis. For example, caries incidence can be reduced through water fluoridation at the community level, topical fluoride treatments can be applied by health care professionals in a wide variety of settings, and fluoridated toothpaste can be used in the home. This section does not include an exhaustive list of oral health preventive measures, but it does describe a range of interventions for which evidence is strong.

The value of preventive services has been recognized for decades. For example, in 1969, Harold L. Applewhite (D.D.S., M.P.H.) stated:

At present, public and professional response to preventive measures lags behind scientific knowledge[. . . .] So far, our present preoccupation with repairing, removing, and replacing teeth have not proven to be successful in the clinical treatment of oral diseases. The rapid changes in the political and socioeconomic situation, and the rapid increase in knowledge of causative factors and preventive measures in oral diseases, do call for a new approach. (Applewhite, 1969)

It has been known for some time that dental caries, like most diseases, has a multifactorial causal pathway, which also provides multiple points at which the disease process could be curtailed (Featherstone, 2004). While there is always room for improvement and advancement, dentistry now has a very effective armamentarium to prevent dental caries. Those preventive interventions include a wide range of fluorides, which generally inhibit the caries process by reducing the rate of enamel demineralization and promoting remineralization. Some modes of fluoride delivery to whole communities involve the addition of very low levels of fluoride to public water systems, salt, or milk (Griffin et al., 2001a). Other forms of fluoride are applied personally or by a caretaker, including fluoride toothpaste and fluoride mouthwashes. Finally, some types of high concentration topical fluoride products are applied by a health care professional. Fluoride supplements, such as drops and chewable tablets, also may be prescribed or dispensed by health care professionals to high-risk children in communities whose water supply is not fluoridated.

Professionally delivered preventive measures also include the application of dental pit and fissure sealants to susceptible tooth surfaces to provide a physical barrier to cariogenic bacteria and their nutrients. Health care professionals may prescribe or dispense antibacterial rinses such as chlorhexidine for bacterial plaque control. Health care professionals also can remove plaque and other deposits from tooth surfaces, provide dietary counseling, and provide or recommend other measures that may prevent or control dental caries.

Aside from clinical effectiveness, many studies support the cost-effectiveness of preventive dental care, often due to the avoided expensive treatments associated with severe dental disease (CDC, 1999c; Lee et al., 2006; Quiñonez et al., 2005; Ruddy, 2007; Weintraub et al., 2001).

Fluoride

The oral health benefits of fluoride have been well known for more than 75 years (CDC, 2010a). Fluoride reduces the risk of caries in both children and adults (Griffin et al., 2007; IOM, 1997; Marinho, 2009; Marinho et al., 2002, 2003a; NRC, 1989; Twetman, 2009; WHO, 2010d). Fluoride works through a variety of systemic and topical mechanisms, including incorporating into enamel before teeth erupt, inhibiting demineralization and enhancing remineralization of teeth, and inhibiting bacterial activity in dental plaque (CDC, 2001; HHS, 2000b). Sources of fluorides include, but are not limited to fluoridated drinking water, mouthwash, toothpaste, and professionally applied fluorides (e.g., fluoride varnish). The broad availability of fluoride products produces a risk for overconsumption of fluoride, which can result in fluorosis, a broad term used to describe the tooth discoloration

associated with excess fluoride intake during the tooth-forming years (0–8 years) (CDC, 2001; HHS, 2000a). The mild fluorosis occasionally caused by fluoride consumption, however, is rarely cause for aesthetic concern let alone health concern, and the risk of fluorosis can be minimized with appropriate use of fluoride products (Alvarez et al., 2009; HHS, 2000b; National Health and Medical Research Council, 2007; Newbrun, 2010).

Fluoridated Water

Community water fluoridation is credited with significantly reducing caries incidence in the United States, and it was recognized as one of the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century (CDC, 1999b). Evidence continues to show that community water fluoridation is effective, safe, and inexpensive, and it is associated with significant cost savings (CDC, 1999c, 2001; Griffin et al., 2001a,b; HHS, 2000b; Horowitz, 1996; Kumar et al., 2010; O’Connell et al., 2005; Parnell et al., 2009; Yeung, 2008). The Task Force on Community Preventive Services recommends community water fluoridation, and it is supported by most health professional associations (ADA, 2010; APHA, 2008; Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2002).

The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) at the NIH was founded in 1931 as the Dental Hygiene Unit, with the mission of investigating the connection between naturally occurring fluoride in water supplies and mottled teeth (i.e., fluorosis) in children (CDC, 1999a). The results of that research indicated children living in areas with high concentrations of fluoride in the water had more “mottled teeth,” but also lower incidence of dental caries (CDC, 1999a). Later field studies established optimal fluoride levels that maximize the oral health benefits while minimizing the fluorosis effects (CDC, 1999b). HHS continues to make recommendations to balance the benefits of preventing tooth decay while limiting any unwanted health effects; the agency recently proposed focusing the optimal fluoride concentration to 0.7 mg of fluoride per liter of water from the original range, set in 1962, of 0.7–1.2 mg/L (HHS, 2011). HHS cited “scientific evidence related to effectiveness of water fluoridation on caries prevention and control across all age groups; fluoride in drinking water as one of several available fluoride sources; trends in the prevalence and severity of dental fluorosis; and current evidence on fluid intake across various ambient air temperatures” as the justification for this change (HHS, 2011).

An increasing number of Americans have access to fluoridated water. The most recent data show that in 2008, more than 72 percent of people who are served by public water systems (64 percent of the entire population) had access to optimally fluoridated water (CDC, 2010b), just shy of

the Healthy People 2010 goal of 75 percent (HHS, 2000a). Individually, 27 states and the District of Columbia have already reached this goal (NCHS, 2011). However, there is a perception in some communities (e.g., among Hispanics) that public water sources are not safe, and thus they frequently substitute bottled water; these individuals are often unaware of whether the bottle water is fluoridated (Hobson et al., 2007; Napier and Kodner, 2008; Scherzer et al., 2010; Sriraman et al., 2009; Weissman, 1997). The clinical effects related to increases in consumption of bottled water are unknown (Newbrun, 2010).

Fluoridated Toothpaste

As with the use of fluoridated water, the efficacy of fluoride toothpastes in preventing dental caries has been well established for decades. In 1960, Crest became the first brand of toothpaste to receive endorsement from the American Dental Association (ADA) for its effectiveness in preventing dental caries (Miskell, 2005). There is strong evidence that daily use of fluoride toothpaste reduces the incidence of caries in children (CDC, 2001; Marinho et al., 2003b; Twetman, 2009). The caries preventive effects are greater with more frequent brushing and when parents supervise (Marinho et al., 2003b). The preventive effects of fluoride toothpaste are likely similar in adults, although few studies have used adults as subjects (CDC, 2001). The evidence for the use of fluoridated toothpaste is high quality, and its use is recommended for all populations (CDC, 2001).

Professionally Applied Fluorides

Fluorides can be professionally applied in the form of varnish or gel. Varnishes are brushed onto clean, dry teeth (Bawden, 1998). The application takes about 1 minute, and the varnish sets quickly. To keep the varnish on the teeth for a number of hours, patients are told to eat soft foods and avoid brushing and flossing for the remainder of the day (Bawden, 1998). Gels are applied to the teeth using gel trays, which must stay on the patient’s teeth for approximately 4 minutes (Bawden, 1998). Increasingly, varnishes are used instead of gels due to the ease of application and low risk of ingestion, especially for younger children (Bawden, 1998). Varnishes and gels are equally effective at preventing caries (Seppä et al., 1995).

Fluoride varnish has been shown to be effective in the prevention of caries in both deciduous and permanent teeth (Marinho et al., 2002). The interval for frequency of application of fluoride varnish varies depending on the risk of the patient—more frequently for children with higher risk (ADA, 2006; Azarpazhooh and Main, 2008). Although use of fluoride varnish for caries prevention is technically considered an “off-label” use, there

is a robust evidence base for the efficacy of varnish at preventing caries (Beltran-Aguilar et al., 2000; Marinho et al., 2002; Weintraub et al., 2006).

Dental Sealants

Dental sealants prevent caries from developing in the pits and fissures of teeth, where caries are most prevalent (Ahovuo-Saloranta et al., 2008). A dental sealant is a thin, protective coating of plastic resin or glass ionomer that is applied to the chewing surfaces of teeth to prevent food particles and bacteria from collecting in the normal pits and fissures and developing into caries. A Cochrane review of sealant studies found that resin-based sealants were effective at preventing caries, ranging from an 87 percent reduction in caries after 12 months to 60 percent at 48–54 months (Ahovuo-Saloranta et al., 2008). Sealants are most effective when placed on fully erupted molars (Dennison et al., 1990). Sealants can also be placed over noncavitated carious lesions to reduce the progression of the lesions (Griffin et al., 2008).

Despite their effectiveness, few children receive sealants. The most recent NHANES (1999–2004) data indicate that 32 percent of 8-year-olds and 21 percent of 14-year-olds have sealants on their permanent molars (Dye et al., 2007). While this is a significant increase over the 23 percent of 8-year-olds and 15 percent of 14-year-olds with sealants in 1988–1994, it falls short of the Healthy People 2010 goal of 50 percent of both groups (Dye et al., 2007; HHS, 2000a). Unfortunately, low-income children, who are most likely to have caries, are the least likely to receive sealants (Dye et al., 2007).

Sealants can be applied in a dental office or in a community-based program, such as school-based sealant programs. Many sealant programs strive to target high-risk populations because this has proven to be effective for the prevention of caries as well as to demonstrate cost savings (Kitchens, 2005; Pew Center on the States, 2010; Weintraub, 1989, 2001; Weintraub et al., 1993, 2001). The evidence that school-based sealant programs decrease decay is strong, and they are recommended by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services (see Chapter 4). However, evidence is insufficient to comment on the effectiveness of less targeted state- or community-wide programs (Truman et al., 2002).

Personal Health Behaviors

While community- and dental-office-based interventions are important for preventing oral diseases, personal behaviors also play an important role in oral health. A healthy diet is important for maintaining oral health, because it reduces the risk for dental caries and oral cancers (Mobley et al., 2009; Moynihan and Petersen, 2004) and potentially periodontal dis-

ease (Merchant et al., 2006; Nishida, 2000a,b; Pihlstrom, 2005). Tobacco and alcohol use are risk factors for oral cancers and periodontal disease (Rethman et al., 2010). Good personal hygiene, including toothbrushing with fluoridated toothpaste, reduces the risk for dental caries (Twetman, 2009). However, changing personal behaviors is a complex task (see discussion later in this chapter about health care behavior change).

Nutrition and Diet

Nutrition and oral health have a two-way relationship: poor nutrition promotes oral diseases, and poor oral health can adversely affect nutrition. For example, studies suggest that loss of teeth is associated with poorer nutritional intake, which may put individuals at risk for other systemic diseases (Hung et al., 2003; Joshipura and Ritchie, 2005). In addition, an insufficient level of folic acid is a risk factor in the development of birth defects such as cleft lip and palate (HHS, 2000b). Dietary carbohydrates are a necessary ingredient in the formation of dental caries (HHS, 2000b; Moynihan and Petersen, 2004), and consuming sugar-rich foods and drinks significantly increases the risk for dental caries (Burt et al., 1988; Grindefjord et al., 1996; Heller et al., 2001; Marshall et al., 2005; Sundin et al., 1992; WHO, 2010b). Carbonated beverages also promote dental erosion due to high acid levels (Ehlen et al., 2008; Kitchens and Owens, 2007). Fruits and vegetable consumption, however, can protect against oral cancers (HHS, 2000b; Pavia et al., 2006; WHO, 2010b).

Tobacco and Alcohol Use

Tobacco is a primary risk factor for oral cancers, the development and progression of periodontal disease, oral cancer recurrence, and congenital birth defects such as cleft lip and palate (Bergström, 2003; Gelskey, 1999; HHS, 2000b; Lebby et al., 2010; WHO, 2010c; Wyszynski et al., 1997). Excessive consumption of alcohol is a risk factor for precancerous and neoplastic lesions as well as oral cancers (HHS, 2000b; WHO, 2010b). When used together, alcohol and tobacco are synergistic in their risk for oral cancers (Rothman and Keller, 1972). Tobacco use and excessive alcohol consumption account for 90 percent of all oral cancers (Truman et al., 2002). Studies have shown that oral health professionals have a role to play in tobacco cessation programs (Albert et al., 2006; Gordon et al., 2010). However, one survey showed that most dentists do not ask their patients about their tobacco use (Albert et al., 2005).

Personal Hygiene

Individuals can also reduce the risk of developing oral disease through personal hygiene, including toothbrushing and flossing. For example, regular toothbrushing with fluoridated toothpaste reduces both caries risk and gingival inflammation (Deery et al., 2004; Marinho, 2009; Marinho et al., 2003a,b; Robinson et al., 2005; Walsh et al., 2010). Some steps that patients can take to improve their own (or their children’s) care include

• Use of topical fluorides including toothpastes and rinses,

• Consumption of fluoridated water,

• Reducing sugar consumption,

• Reducing the numbers of sugar exposures each day (i.e., eliminating or minimizing snacks and/or changing the type of snack food to noncariogenic), and

• Not putting an infant or child to bed with a bottle that contains anything but water.

Nearly all aspects of oral health care use require literacy. Beyond just the ability to read, write, and communicate effectively, literacy addresses the patient’s ability to successfully navigate the health care system to obtain needed care services or perform self-care. Examples include completing a Medicaid application, scheduling a dental appointment, determining how much fluoride toothpaste to use on a toddler’s toothbrush, understanding media campaigns, and weighing the potential complications of a root canal. While there is ample evidence supporting the association between general health and health literacy, very little research has been done specifically in oral health literacy. The role and current activities of HHS related to health literacy are discussed in Chapter 4.

What Is Oral Health Literacy?

Consensus has developed around the National Library of Medicine’s definition of health literacy (IOM, 2004; Selden et al., 2000), which has been adapted for oral health: “Oral health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic oral and craniofacial health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (NIDCR, 2005). This definition excludes both provider and system-level contributions to oral health literacy, but despite these limitations, the IOM Committee on Health Literacy, Healthy People

2010, and the NIDCR all use this definition of oral health/health literacy (HHS, 2000a; IOM, 2004; NIDCR, 2005).

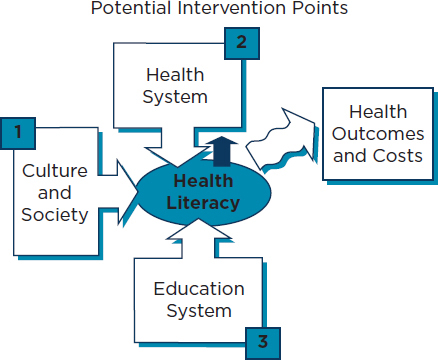

An individual’s success at making these oral health-related decisions is based partially on his or her own literacy, but most experts agree that an individual’s health literacy depends heavily on system-level contributions. Three sectors are responsible for and have the potential to build health literacy: culture and society, the health system, and the educational system (IOM, 2004). The interaction between these sectors and health literacy is illustrated in Figure 2-1.

Culture and Society

Health literacy is inextricably linked with culture and society, which includes factors such as race, ethnicity, native language, socioeconomic status, gender, and age, as well as influences such as media, advertising, marketing, and the Internet. Culture provides the context for understanding illness, di-

FIGURE 2-1

Intervention points for health literacy.

SOURCE: IOM, 2004.

agnoses, and health care messages. Different cultures use different communication styles, ascribe different meaning to words and gestures, and have different comfort levels in discussing the body, health, and illness (IOM, 2004). Health literacy requires communication and mutual understanding between patients and their families and health care professionals and staff about these differences (IOM, 2004). Cultural competence training may be an important step in improving health outcomes, although evidence has not yet established that link (Betancourt and Green, 2010; Hewlett et al., 2007; Novak et al., 2004; Pilcher et al., 2008; Wagner and Redford-Badwal, 2008; Wagner et al., 2007, 2008). Cultural competence includes linguistic competence—health professionals must also address language barriers for patients who have limited English proficiency (IOM, 2004). Recognizing the importance of culture on health literacy and health care outcomes,in 2001 HHS published National Standards on Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS standards) in health care (OMH, 2001). These standards are discussed in further detail in Chapter 4.

The Health System

The organization of the health system can also enhance or inhibit health literacy. Currently, the literacy demands in the U.S. health care system exceed the health literacy skills of most adults (IOM, 2004). Navigating the system requires understanding complicated bureaucracy, a fragmented delivery system, and complex medical jargon. Even highly literate individuals struggle to make sense of the large amounts of information required to function effectively in the health care system. The problem of low health literacy is exacerbated and is becoming more apparent by the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, including dental caries, that require long-term self-management by patients and the limited amount of time professionals have to spend with patients (OMH, 2001).

Individual practitioners, health organizations, and HHS can all take action to mitigate the effects of low health literacy. Health care professionals can make an effort to use plain language, slow down, show drawings or pictures, limit the amount of information provided and repeat it, use the teach-back method, and create an environment where patients feel comfortable asking questions (Schwartzberg et al., 2007; Weiss, 2007). Organizations can improve the readability of written materials, standardize medication labels and information, follow up with patients by phone, train health care professionals in communication skills and cultural competence, help patients navigate through the system, and coordinate care across multiple providers (DeWalt et al., 2006, 2010; Rothman et al., 2004; Sudore and Schillinger, 2009). Health professional schools and licensing bodies can teach evidence-based and culturally competent communication

skills in schools and continuing medical education courses (Cannick et al., 2007; Carey et al., 2010; Eiser and Ellis, 2007; IOM, 2003). Health care professionals and provider organizations must recognize and address literacy, culture, and native language in their health literacy efforts. HHS can sponsor, conduct, and disseminate research on interventions to improve communication for patients with low health literacy, since few techniques have been rigorously evaluated.

The Education System

The education system is where most individuals develop both basic literacy skills and health knowledge, and therefore it plays a critical role in developing health literacy. Students learn health knowledge through health education programs provided in elementary, middle, and high schools. See Chapter 4 for more on the role of public education in improving health literacy.

Knowledge

Knowledge about health care topics is sometimes included in the definition of health literacy (IOM, 2004), and sometimes it is regarded as a resource that facilitates literacy (Baker, 2006). In either case, correct, evidence-based knowledge about health topics allows individuals and health care professionals to make informed health care decisions and recommendations, and to interact more effectively in health care contexts.

The Importance of Health Literacy

Health literacy is important because it can affect health care use, patient outcomes, and overall health care costs. Adults with limited health literacy have less knowledge of disease management and of health-promoting behaviors, report poorer health status, and are less likely to use preventive services (Arnold et al., 2001; DeWalt et al., 2004; IOM, 2004; Scott et al., 2002; Williams et al., 1998). People with low health literacy have adverse health outcomes (DeWalt et al., 2004; Mancuso and Rincon, 2006; Wolf et al., 2005). In addition, parents with low literacy make health care decisions that are less advantageous to their children, and their children have poorer health outcomes (DeWalt and Hink, 2009; Miller et al., 2010; Sanders et al., 2009). Currently, there is little consensus about the best ways to improve health outcomes for people with low health literacy (Pignone et al., 2005). Medical errors can occur when patients do not understand instructions provided by a doctor. In fact, one study found that nearly half of all pediatricians surveyed reported being aware of a communication-related

medical error in the past 12 months (Turner et al., 2009). The HHS Office of Minority Health noted in the final report on CLAS standards that “[e]rrors made due to cultural or linguistic misunderstandings in health care encounters can lead to repeat appointments, extra time spent rectifying misdiagnoses, unnecessary emergency room visits, longer hospital stays, and canceled diagnostic or surgical procedures” (OMH, 2001). Poor health literacy is also expensive; it contributes significantly to both overall health care costs and individual expenditures (Eichler et al., 2009; Howard et al., 2005; Vernon et al., 2007; Weiss and Palmer, 2004).

Not enough is known specifically about oral health literacy. The NIDCR Workgroup on Oral Health Literacy proposed a research agenda for oral health literacy in 2005 (NIDCR, 2005). Progress has been slow; researchers have developed instruments to measure oral health literacy, although more work must be done to assess their validity (Atchison et al., 2010; Gong et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007; Richman et al., 2007; Sabbahi et al., 2009).

Oral Health Literacy of the Public

All available measures indicate that the public’s health literacy in general and oral health literacy in particular is poor. In 2003, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy assessed the health literacy of adult Americans on a large scale for the first time. It determined that only 12 percent of adults had proficient health literacy (Kutner et al., 2006). One study that specifically investigated the oral health literacy of patients in a clinical setting found poor oral health literacy was strongly associated with self-reported poor oral health status and lower dental knowledge (Jones et al., 2007).

The public has little knowledge about the best ways to prevent oral diseases. Fluoride and dental sealants (for children) have long been acknowledged as the most effective ways to prevent dental caries, yet the public consistently answers that toothbrushing and flossing are more effective (Ahovuo-Saloranta et al., 2008; Gift et al., 1994; Marinho et al., 2003a). When asked to choose the best way to prevent tooth decay from five options, only 7 percent of respondents to the National Health Interview Survey correctly answered using fluoride, while 70 percent answered that brushing and flossing were most effective (Gift et al., 1994). Further, only 23 percent of respondents knew the purpose of dental sealants. Other studies show that the public remains generally unaware of the transmissible, infectious nature of dental caries, including that the bacteria involved in the etiology of the disease can be passed from caretaker to child through the sharing of food and utensils and by kissing (Gussy et al., 2008; Sakai et al., 2008).

Much of the oral health literacy literature focuses on knowledge (or

lack of knowledge) about oral and pharyngeal cancer. Although each year more than 30,000 Americans are diagnosed with these cancers and nearly 8,000 people die from them, the public’s knowledge about the risk factors and symptoms of oral cancers is low (ACS, 2009; Cruz et al., 2002; Horowitz et al., 1998, 2002; Patton et al., 2004). While 85 percent of respondents to a telephone survey had heard of oral cancer, only 23 percent of those could name one early symptom (Horowitz et al., 1998). Many people also could not identify common risk factors for oral cancer. Although 67 percent of adults responding to the 1990 National Health Interview Survey knew that tobacco use is a risk factor for oral cancer, very few respondents knew about any other risk factors (Horowitz et al., 1995).

Oral Health Literacy of Health Care Professionals

All health care professionals can facilitate literacy by communicating clearly and accurately. This requires them to have good communication skills and knowledge related to oral health. Recognizing literacy as an important issue in oral health, the ADA recently developed a strategic action plan that provides guidance (but not requirements) on principles, goals, and strategies to improve health literacy in dentistry (ADA, 2009). Strategies include facilitating the development, testing, distribution, and evaluation of a health literacy training program for dentists and other members of the oral health team, investigating the feasibility of a systematic review of the health literacy literature, and encouraging oral health education in schools (ADA, 2009).

Communication Skills

In general, health care professionals can help by assessing patients’ health literacy and communicating at an appropriate level of complexity. However, health care professionals are generally not trained in how to perform such an assessment and do not account for the low health literacy of patients when communicating health information. Practitioners often use medical jargon, provide too much information at once, and fail to confirm that the patient understood the information provided (Williams et al., 2002). While nearly all professionals surveyed report using at least one technique to improve communication with patients, fewer than half use the techniques shown to be most effective—indicating key points on written materials and the “teach-back” method, where professionals ask patients to repeat back the information (Schwartzberg et al., 2007; Turner et al., 2009).

At this IOM committee’s second meeting, the ADA presented preliminary findings of a survey on the communication skills of members of

the dental team (Neuhauser, 2010). This study aimed to determine the techniques that are used by dentists and dental team members to communicate effectively with their patients; examine variation in the use of these techniques; and explore the different variables that might be targeted in the future to improve communication and dental practices. Findings included a high amount of variation in the type and number of communication techniques used, and the use of more techniques by older dentists, by dentists from racial and ethnic populations, and by dentists who are specialists (e.g., oral surgeons). Routine use of communication techniques is low among dentists, especially some techniques such as the teach-back method, thought to be most effective with patients with low literacy. Nearly two-thirds of the dentists said they did not have training in health literacy and clear communication.

Improving the communication skills of oral health care professionals may require curricular changes in both health professional schools and continuing dental education programs. The Commission on Dental Accreditation (the accrediting body for dental schools) requires schools to ensure that dental students “have the interpersonal and communications skills to function successfully in a multicultural work environment” (CODA, 2010). In addition, the American Dental Education Association (the professional organization for dental education schools) has established competencies for the new general dentist that include “apply[ing] appropriate interpersonal and communication skills, apply[ing] psychosocial and behavioral principles in patient-centered health care, and communicat[ing] effectively with individuals from diverse populations” (ADEA, 2009). Despite these standards, few schools have adopted a competency exam for communication (Cannick et al., 2008). Further, unlike in medicine, the national dental licensing exam does not include a clinical component that assesses communication skills (JCNDE, 2011; USMLE, 2010). Continuing education courses can also improve the communication skills of providers (Barth and Lannen, 2010; Levinson and Roter, 1993), yet at least one state does not allow continuing education credit for courses taken in communication.2

Oral Health Knowledge

As patients of all ages often visit primary care professionals more frequently than they visit dentists, these practitioners are in a good position to provide basic oral health education. For example, 90-plus percent of practicing pediatricians think they play an important role in identifying oral health problems and counseling parents about the importance of oral health (Lewis et al., 2000). Even more dramatically, nearly all (99 per-

![]()

2 49 Pa. Cons. Stat. §33.402 (2011).

cent) of the residents graduating from pediatric residency programs believe pediatricians should educate parents about the effects of their children sleeping with a baby bottle and drinking juice and carbonated beverages, and a significant percentage think pediatricians should identify cavities (89 percent), and teach patients how to brush correctly (86 percent) (Caspary et al., 2008). Despite this, pediatricians lack the necessary knowledge about basic oral health to educate patients about oral health issues or screen for oral disease. Thirty-five percent of pediatric residents receive no oral health training during their residency, and 73 percent of those who do receive training spend less than 3 hours on oral health (Caspary et al., 2008). This is significant because physicians’ oral health care practices improve with training. Graduating residents with more than 3 hours of oral health training were significantly more likely to feel confident performing oral health education and assessments (Caspary et al., 2008). Additionally, osteopathic medical students who received 2 days of oral health education showed dramatically improved oral health knowledge (Skelton et al., 2002). (The education and training of health care professionals in oral health is discussed further in Chapter 3.)

Similar patterns are seen in other types of health care professionals as well as for other oral diseases. For example, one study of internal medicine trainees showed that only 34 percent correctly answered all five general knowledge questions on periodontal disease; 90 percent of the trainees stated they did not receive any training regarding periodontal disease during medical school (Quijano et al., 2010). In a 2009 study by Applebaum et al., only 9 percent of primary care physicians could identify the two most common sites for oral cancers, and only 24 percent knew the most common symptom of early oral cancer (Applebaum et al., 2009). In a survey of nurse practitioners, only 35 percent identified sun exposure as a risk for lip cancer, and only 19 percent thought their knowledge of oral cancers was current (Siriphant et al., 2001). A survey of nursing assistants in nursing homes found that the nursing assistants generally regarded tooth loss as “a natural consequence of aging” (Jablonski et al., 2009).

The few surveys that have investigated the oral health knowledge of dentists and hygienists have found it lacking. In a national survey, fewer than 50 percent of dental hygienists knew that dental caries was a chronic infectious disease, and many did not recognize the value of fluoride in preventing dental caries (Forrest et al., 2000). In a survey about knowledge of oral cancer risk factors, dentists averaged 8.4 correct answers out of 14, and hygienists averaged 7.9 correct answers (Yellowitz et al., 2000). When asked about oral cancer diagnostic procedures; dentists averaged six correct answers out of nine, but more than one-third answered four or fewer answers correctly (Yellowitz et al., 2000). In the above-cited study by Applebaum et al. (2009), 39 percent of dentists could identify the two most

common oral cancer sites and 57 percent could identify the most common symptom of early oral cancer (Applebaum et al., 2009). Although 98 percent of dental hygienists responded that adults over age 40 should receive an oral cancer examination annually, only 66 percent report providing the exam all of the time, and an additional 10 percent report doing so some of the time (Forrest et al., 2001).

Behavior Change

While a full examination of the evidence base and approaches for behavior change is beyond the scope of this report, it is important to note that improving health literacy is just the beginning of the behavioral change process. A number of factors make behavior change very difficult, including cultural norms, individual preferences, economic factors, and the role of the larger society (Glanz and Bishop, 2010; IOM, 2000; McLeroy et al., 1988). Simply providing information is generally not sufficient to modify patients’ behaviors or change their attitudes (Freeman and Ismail, 2009; Satur et al., 2010). A 2000 IOM report on social and behavioral research stated:

To prevent disease, we increasingly ask people to do things that they have not done previously, to stop doing things they have been doing for years, and to do more of some things and less of other things. Although there certainly are examples of successful programs to change behavior, it is clear that behavior change is a difficult and complex challenge. It is unreasonable to expect that people will change their behavior easily when so many forces in the social, cultural, and physical environment conspire against such change. (IOM, 2000)

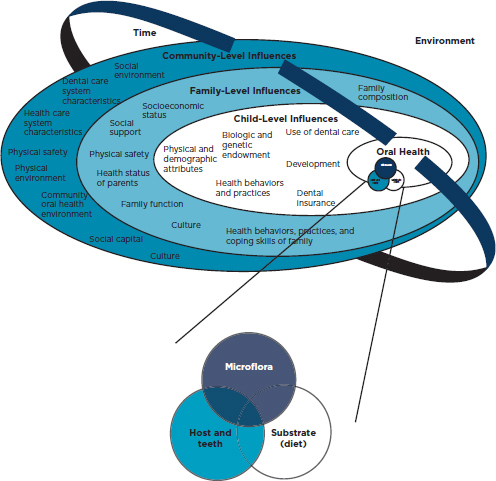

In oral health care, behavior change requires attention to individuals (e.g., personal health behaviors), families (e.g., family stress, social support), health care professionals (e.g., appropriate counseling techniques), the environment (e.g., accessibility to oral health care, status of community water fluoridation), and cross-cutting issues (e.g., racial and ethnic health disparities, cultural preferences) (Finlayson et al., 2007; Glanz, 2010; Kelly et al., 2005; Quinoñez et al., 2000). This is illustrated graphically in Figure 2-2. Despite the difficulties in influencing health behaviors, there are promising behavioral change models. One example is motivational interviewing, a “directive, client-centered counseling style for eliciting behavior change by helping clients to explore and resolve ambivalence” (Rollnick and Miller, 1995). Motivational interviewing has been shown to improve a variety of health behaviors and conditions, including smoking cessation and dental caries (Freudenthal and Bowen, 2010; Lai et al., 2010; Miller, 1983; Naar-King et al., 2009; Rubak et al., 2005; Weinstein et al., 2006).

FIGURE 2-2

Conceptual of model of oral health and the influences on oral health.

SOURCE: Fisher-Owens et al., 2007. Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, Vol. 120, Pages 510–520, Copyright © 2007 by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The committee noted the following key findings and conclusions:

Oral Health and Overall Health

• Oral health is inextricably linked to overall health.

Oral Health Status

• The overall oral health status of the U.S. population is improving, but significant disparities remain for many vulnerable populations. Therefore, HHS’ efforts need to focus on populations with the greatest need.

• Discrete segments of the U.S. population have difficulty accessing oral health care services.

• Fourteen percent of children 6–12 years old have had toothache severe enough during the past 6 months to have complained to their parents.

Prevention

• Seventy-two percent of people who are served by public water systems (64 percent of the entire population) have access to optimally fluoridated water.

• There is a strong evidence base to support the effectiveness many oral disease prevention interventions (e.g., community water fluoridation, fluoride varnish, and sealants).

• The public and many health care professionals are generally unaware of the causes and consequences of oral diseases and the ways in which these diseases can be prevented.

Health Literacy

• Oral health care professionals often do not use the best techniques to communicate with their patients. Oral health care professionals need to be be trained in effective communication and cultural competence.

• Further improvements to the oral health of the U.S. population will require behavior change at many levels (e.g., individual, families, communities, and nationally), but little is known about the best ways to encourage those changes.

• Poor oral health literacy contributes to poor access because individuals may not understand the importance of oral health care or their options for accessing such care.

ACOG (American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). 2004. Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology 104(3):647-651.

ACS (American Cancer Society). 2009. Cancer facts and figures 2009. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

ADA (American Dental Association). 2006. Professionally applied topical fluoride: Evidence-based clinical recommendations. Journal of the American Dental Association 137(8):1151-1159.

ADA. 2009. Health literacy in dentistry action plan 2010-2015. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association.

ADA. 2010. Fluoride & fluoridation. http://www.ada.org/2467.aspx (accessed September 16, 2010).

ADEA (American Dental Education Association). 2009. Competencies for the new general dentist. Journal of Dental Education 73(7):866-869.

Ahovuo-Saloranta, A., A. Hiiri, A. Nordblad, H. Worthington, and M. Mäkelä. 2008. Pit and fissure sealants for preventing dental decay in the permanent teeth of children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4):CD001830.

Al Habashneh, R., J. M. Guthmiller, S. Levy, G. K. Johnson, C. Squier, D. V. Dawson, and Q. Fang. 2005. Factors related to utilization of dental services during pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 32(7):815-821.

Al-Hashimi, I. 2001. The management of Sjögren’s syndrome in dental practice. Journal of the American Dental Association 132(10):1409-1417.

Albert, D. A., H. Severson, J. Gordon, A. Ward, J. Andrews, and D. Sadowsky. 2005. Tobacco attitudes, practices, and behaviors: A survey of dentists participating in managed care. Nicotine and Tobacco Research 7(Supp. 1):S9-S18.

Albert, D. A., H. H. Severson, and J. A. Andrews. 2006. Tobacco use by adolescents: The role of the oral health professional in evidence-based cessation programs. Pediatric Dentistry 28(2):177-187.