While the connections between oral health and overall health and well-being have been long established, oral health care and general health care are provided in almost entirely separate systems. Oral health is separated from overall health in terms of education and training, financing, workforce, service delivery, accreditation, and licensure. In the United States, medical and dental education and practice have been separated since the establishment of the first dental school in Baltimore in 1840 (University of Maryland, 2010). The financing of oral health care is characterized by a similar divide. For example, private health plans typically do not cover oral health care, and the benefits package for Medicare excludes oral health care almost entirely. These separations contribute to obstacles that impede the coordination of care for patients.

This chapter provides an overview of the oral health care system in America today—where services are provided, how those services are paid for, who delivers the services, how the workforce is educated and trained to provide these services, and how the workforce is regulated. The role of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in oral health education and training, as well as in supporting the delivery of oral health care services, will be addressed in Chapter 4 of this report. Detailed examination of the role HHS plays in overseeing safety net providers such as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs1) was charged to the concurrent Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Oral Health Access to

![]()

1 A Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) is any health center that receives a grant established by section 330 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. §254b).

Services. Therefore, this committee limited its examination of the safety net in this current report.

The current oral health care system is composed of two basic parts—the private delivery system and the safety net—and there is little integration of either sector with wider health care services. The two systems function almost completely separately; they use different financing systems, serve different clientele, and provide care in different settings. In the private delivery system, care is usually provided in small, private dental offices and financed primarily through employer-based or privately purchased dental plans and out-of-pocket payments. This model of care has remained relatively unchanged throughout the history of dentistry. The safety net, in contrast, is made up of a diverse and fragmented group of providers who are financed primarily through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), other government programs, private grants, as well as out-of-pocket payments.

In addition, some oral health care, especially for young children, has begun to be supplied by nondental providers in settings such as physicians’ offices, which is discussed later in this chapter. This section gives a brief overview of the basic settings of oral health care by dental professionals—namely, dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants. The professionals themselves will be discussed later in this chapter.

The Private Practice Model

The structure of private practice provides dentists with considerable autonomy in their practice decisions (Wendling, 2010). Private practices tend to be located in areas that have the population to support them; thus, there are more practices located in urban areas than in rural, and more practices in high-income than in low-income areas (ADA, 2009b; Solomon, 2007; Wall and Brown, 2007). About 92 percent of professionally active dentists work in the private practice model (ADA, 2009d) (see Box 3-1 for definitions of types of dentists). Among all active private practice dentists (whose primary occupation was private practice), about 84 percent are independent dentists, 13 percent are employed dentists, and 3 percent are independent contractors (ADA, 2009d). About 60 percent of private practice dentists are solo dentists (Wendling, 2010). In addition, 80 percent of all active private practitioners and 83 percent of new active private practitioners are in general practice, while the remainder work in one of many specialty areas (see Table 3-1).

Dentists in the private practice setting see a variety of patients. The

BOX 3-1

Types of Dentists

A professionally active dentist is primarily or secondarily occupied in a private practice, dental school faculty/staff, armed forces, or other federal service (e.g., Veterans Administration, U.S. Public Health Service); or is a state or local government employee, hospital staff dentist, graduate student/intern/resident, or other health/dental organization staff member.

An active private practitioner is someone whose primary and/or secondary occupation is private practice.

A new dentist is anyone who has graduated from dental school within the last 10 years.

An independent dentist is a dentist running a sole proprietorship or one who is involved in a partnership.

A solo dentist is an independent dentist working alone in the practice he or she owns.

A nonowner dentist does not share in ownership of the practice.

An employed dentist works on a salary, commission, percentage, or associate basis.

An independent contractor contracts with owner(s) for use of space and equipment.

A nonsolo dentist works with at least one other dentist and can be an independent or nonowner dentist.

NOTE: Each of these types can be either general or specialty practitioners.

SOURCES: ADA, 2009b,d.

patients of independent general practitioners are spread relatively evenly across the age spectrum and equally divided by gender (ADA, 2009b). About two-thirds (63 percent) of their patients have private insurance; only about 7 percent receive publicly supported dental coverage, and the remaining 30 percent are not covered by any dental insurance (ADA, 2009b). Similarly, independent dentists’ billings primarily are from private insurance and direct patient payments (44 percent and 39 percent, respectively) (ADA, 2009c). Nearly two-thirds of independent dentists (63 percent) and slightly more than half of new independent dentists (58 percent) do not have any patients in their practices covered by public sources (ADA, 2009b). However, in 2006, Bailit and colleagues estimated that 60 to 70 percent of underserved individuals who get care do so in the private care system (Bailit et al., 2006). While there is some disagreement as to whether dentists who care for patients with public coverage are considered part of

TABLE 3-1

Percentage Distribution of Active Private Practitioners by Practice, Research, or Administration Area, 2007

| Practice, Research, or Administration Area | All Active Private Practitioners | New Active Private Practitioners |

| General practice | 80.1 | 83.3 |

| Orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics | 5.7 | 4.7 |

| Oral and maxillofacial surgery | 3.7 | 1.9 |

| Periodontics | 2.8 | 1.7 |

| Pediatric dentistry | 3.0 | 4.4 |

| Endodontics | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Prosthodontics | 1.6 | 0.8 |

| Public health dentistry | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Oral and maxillofacial pathology | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Oral and maxillofacial radiology | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Missing specialty area | 0.1 | 0.1 |

SOURCE: ADA, 2009d.

the safety net, opportunities to expand care for vulnerable and underserved populations in private settings cannot be overlooked.

The Oral Health Safety Net

Some segments of the American population, namely socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, have difficulty accessing the private dental system due to geographic, financial, or other access barriers and must rely on the dental safety net (if they are seeking care) (Bailit et al., 2006; Brown, 2005; Wendling, 2010). While the term safety net may give the impression of an organized group of providers, the dental safety net comprises a group of unrelated entities that both individually and collectively have very limited capacity (Bailit et al., 2006; Edelstein, 2010a). One estimate of the current capacity of the safety net suggests that 7 to 8 million people may be served in these settings annually, and approximately another 2.5 million could be served with improved efficiency (Bailit et al., 2006). However, the safety net as it exists simply does not have the capacity to serve all of the people in need of care, which is estimated to be as high as 80 to 100 million individu-

als (Bailit et al., 2006; HHS, 2000). While there is a perception that the care provided in safety net settings is somehow inferior to the care provided in the private practice setting, there are no data to support this assumption. In fact, there are very little data regarding the quality of oral health care provided in any setting (see later in this chapter for more on quality assessment in the oral health care system).

Common types of safety net providers include FQHCs, FQHC look-alikes,2 non-FQHC community health centers, dental schools, school-based clinics, state and local health departments, and community hospitals. Each type of provider offers some type of oral health care, but the extent of the services provided and the number of patients served varies widely and the safety net cannot care for everyone who needs it (Bailit et al., 2006; Edelstein, 2010a). Private sector efforts to supplement the safety net include the organization of single-day events to provide free dental care. In 2003, the ADA established the annual Give Kids a Smile Day; in 2011, the ADA estimated the event would involve about 45,000 volunteers providing care to nearly 400,000 children (ADA, 2011a). Another example includes the Missions of Mercy, which are often organized by state dental societies or private foundations. At these events, thousands of individuals have waited in lines for hours to receive care (Dickinson, 2010). These types of single-day events provide temporary relief to the access problem for some people, but they do not provide a regular source of care for people in need.

Multiple challenges exist in the financing of oral health care in the United States, including state budget crises, the relative lack of dental coverage, a payment system (like in general health care) that rewards treatment procedures rather than health promotion and disease prevention, and the high cost of dental services. Expenditures for dental services in the United States in 2009 were $102.2 billion, less than 5 percent of total spending on health care, a proportion that has remained fairly constant for the last two decades (CMS, 2011c).

Demand for dental care may vary with the economic climate of the country (Guay, 2005; Wendling, 2010). For example, the recent recession was identified as a key factor contributing to 2009 having the slowest rate of growth in health spending (4 percent) in the last 50 years (Martin et al., 2011). Notably, expenditures on dental services had a negative rate of

![]()

2 FQHC look-alikes must meet all of the statutory requirements of FQHCs, but they do not receive grant funding under section 330 and are eligible for many, but not all, of the benefits extended to FQHCs.

growth (–0.1 percent) in 2009, down from a positive rate of growth of 5.1 percent in 2008.

Typical sources of health care insurance—Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and employers of all sizes—often do not include dental coverage, especially for adults. Employment status of adults ages 51–64 is a strong predictor of dental coverage (Manski et al., 2010c), and “routine dental care” is specifically excluded from the traditional Medicare benefits package. High-income older adults are more likely to have dental coverage than are other older adults (Manski et al., 2010c). In any case, individuals with dental coverage often incur high out-of-pocket costs for oral health care (Bailit and Beazoglou, 2008). Estimates regarding the severity of uninsurance for dental care include the following:

• In 2000, the surgeon general’s report estimated that 108 million people (about 35 percent of the population) lacked dental coverage (HHS, 2000).

• A recent estimate based on enrollment in private dental plans found 130 million U.S. adults and children lack dental coverage (NADP, 2009).

• In 2004, 34 percent of adults ages 21–64 and about 70 percent of adults ages 65 and older lacked dental coverage (Manski and Brown, 2007).

• Nearly 25 percent of people who have private health insurance lack dental coverage (Bloom and Cohen, 2010).

Overall, rates of uninsurance for oral health care are almost three times the rates of uninsurance for medical care—34.6 percent (Manski and Brown, 2007) versus 14.7 percent (CDC, 2009).

Financing of oral health care greatly influences where and whether individuals receive care. For example, the national Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data show that in 2004, 57 percent of individuals with private dental coverage had at least one dental visit, compared to 32 percent of those with public dental coverage and 27 percent of uninsured individuals (Manski and Brown, 2007). At the individual level, insurance coverage and socioeconomic factors play a significant role in access to oral health care (Flores and Tomany-Korman, 2008; GAO, 2008; Isong et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2007). Financing also has an effect on providers’ practice patterns, in part due to the low reimbursement rates of public insurers. Previous studies have shown that like in medicine, dentists’ practice patterns are associated with financial incentives (Atchison and Schoen, 1990; Naegele et al., 2010; Porter et al., 1999). The following sections give a general overview of how care is financed in the United States.

Private Sources

As shown in Table 3-2, dental care is financed primarily through private sources, including individual out-of-pocket payments and private dental plans.

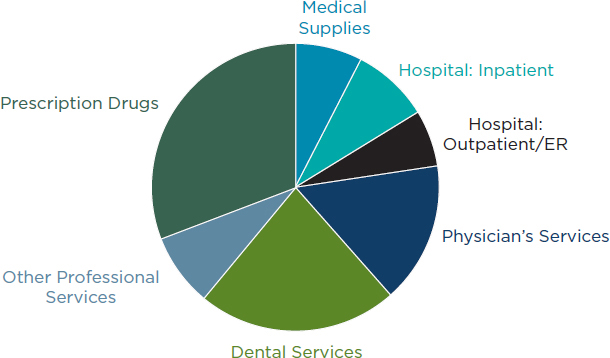

In 2008, dental services accounted for 22 percent of all out-of-pocket health care expenditures, ranking second only to prescription drug expenditures (see Figure 3-1).

Employers can add a separate oral health product to their overall coverage package, but often they do not. In 2006, 56 percent of all employers offered health insurance, but only 35 percent offered dental insurance (Manski and Cooper, 2010). The availability of dental coverage through one’s employer is associated with the size of the establishment; that is, the larger the number of employees overall, the higher the incidence of stand-alone dental plans available to employees (Barsky, 2004; Ford, 2009). Higher-paid workers are also more likely to have access to and participate in stand-alone dental plans (Barsky, 2004; Ford, 2009). Employees are more likely to be offered access to medical insurance than dental insurance, and a higher percentage of employees will take advantage of available dental benefits as compared with the percentage of employees who take advantage of available medical benefits (BLS, 2010b).

TABLE 3-2

National Health Expenditures by Type of Expenditure and Source of Funds, 2009

| Type of Expenditure | Total Spending (billions) | Percentage from Out-of-Pocket Payments (%) | Percentage from Private Insurance (%) | Percentage from Public Insurance (%) |

| Dental services | 102.2 | 41.6 | 48.9 | 9.1 |

| Physician and clinical services | 505.9 | 9.5 | 47.0 | 33.5 |

| Home health care | 68.3 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 80.2 |

| Nursing and continuing care | 137.0 | 29.1 | 7.7 | 56.2 |

| Prescription drugs | 249.9 | 21.2 | 43.4 | 33.9 |

| Hospital care | 759.1 | 3.2 | 35.0 | 53.2 |

NOTES: Public insurance includes Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Totals do not reach 100% as some expenditures were attributed to “Other Third Party Payers and Programs.”

SOURCE: CMS, 2011b.

FIGURE 3-1

Out-of-pocket health care expenditures, 2008.

SOURCE: BLS, 2010a.

Public Sources

Of the $102.2 billion in dental expenditures, nearly 91 percent came from private funds (e.g., private insurance and out-of-pocket payments), and only 9 percent came from public funds (e.g., state and federal funds) (CMS, 2011b). In comparison, public funds account for about one-third of physician and clinical services (see Table 3-2). However, the reported national expenditure levels likely undercount the total public funds spent on improving oral health, because that total represents only the costs associated with direct services delivered by dentists (to the exclusion of the broader definition of oral health) and does not account for care provided in settings such as hospitals and nursing homes. While a much lower percentage of funds for dental services come from public sources as compared to the funding of many other services, the government may, in fact, have a very important role to play for those who cannot afford to pay for care.

Public sources are an important source of coverage for many vulnerable and underserved populations, but a recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that finding providers to care for Medicaid populations “remains a challenge” (GAO, 2010). Low reimbursement by public programs is often cited as a disincentive for providers’ to participate in publicly funded programs (Damiano et al., 1990; GAO, 2000; Lang and Weintraub, 1986; McKnight-Hanes et al., 1992; Venezie et al., 1997). Studies have shown, though, that in order to significantly increase participation rates, increased reimbursement is necessary but often

requires additional efforts such as decreasing the administrative burdens of participation; changing provider perceptions of participating; and fostering relationships among state Medicaid staff, the state dental association, and local dentists (Borchgrevink et al., 2008; GAO, 2000; Greenberg et al., 2008; Wysen et al., 2004).

Medicaid and CHIP

Dental coverage is required for all Medicaid-enrolled children under age 21 (CMS, 2011a). This is a comprehensive benefit, including preventive, diagnostic, and treatment services. According to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid provides health care coverage to nearly 30 million children while CHIP covers an additional 6 million (KFF, 2011). Further, they note that together, Medicaid and CHIP provide health care coverage for one-third of children and over half (59 percent) of low-income children. However, exact documentation of these numbers may be challenging due to how enrollees are counted (e.g., at a point in time versus at any time in a given period).

Regarding the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) Program, by law,3 states must cover any Medicaid-covered service that would reasonably be considered medically necessary to prevent, correct, or ameliorate children’s physical (including oral) and mental conditions. In contrast, Medicaid dental benefits are not required for adults, and even among those states that offer dental coverage for adult Medicaid recipients, the benefits are often limited to emergency care (ASTDD, 2011c). In FY2008, Medicaid spending on dental services accounted for 1.3 percent of all Medicaid payments (CMS, 2010b).

CHIP is a federally funded grant program that provides resources to states to expand health coverage to uninsured, low-income children. Millions of children have received coverage for medical care, and a portion of those have also been covered for dental care (Brach et al., 2003). The Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA)4 enacted in February 2009 requires all states to provide dental coverage to children (but not including their parents) covered under CHIP.

Medicare

As increasing numbers of baby boomers become eligible for Medicare, considerable attention is being paid to how these aging adults will pay for

![]()

3 42 U.S.C. §1396d(r)(3).

4 Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009, Public Law 3, 111th Cong., 1st sess. (February 4, 2009).

and obtain oral health care (Ferguson et al., 2010; Manski et al., 2010a,b,c; Moeller et al., 2010). In the year 2000, almost 77 percent of dental care for older adults was paid by out-of-pocket expenditures, and 0.4 percent was covered by Medicaid (Brown and Manski, 2004). Medicare explicitly excludes coverage for routine dental care, specifically “for services in connection with the care, treatment, filling, removal, or replacement of teeth or structures directly supporting the teeth.”5

In the initial Medicare program, “routine” physical checkups and routine foot care were excluded; comparatively, all dental services were excluded, not just “routine” dental services (CMS, 2010a). In 1980, Congress made an exception for “inpatient hospital services when the dental procedure itself made hospitalization necessary” (CMS, 2010a). Box 3-2 delineates the extent of the exclusion of oral health care from the Medicare program.

Federal Systems of Care

In addition to the public programs noted above, the federal government both directly provides and pays for the oral health care of several distinct segments of the U.S. population. This includes care provided both in public and private settings through the various branches of the military, the Bureau of Prisons, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Veterans Administration. The role of the federal government in providing care is discussed more fully in Chapter 4.

Impact of Health Care Reform

Between now and 2014, several provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)6 will affect dental coverage. For example, provisions address coverage of oral health services for children and the expansion of Medicaid eligibility. Table 4-4 in Chapter 4 highlights some of the key provisions that will affect dental coverage.

Traditionally, a combination of dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants directly provide oral health care. Dental laboratory technicians create bridges, dentures, and other dental prosthetics. In addition, new and evolving types of dental professionals (e.g., dental therapists) are being pro-

![]()

5 Social Security Act, §1862(a)(12).

6 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 148, 111th Cong., 2nd sess. (March 23, 2010).

BOX 3-2

Exclusions (and Exceptions) to

Dental Coverage Under Medicare

Services Excluded Under Part B

A primary service (regardless of cause or complexity) provided for the care, treatment, removal, or replacement of teeth or structures directly supporting teeth (e.g., preparation of the mouth for dentures, removal of diseased teeth in an infected jaw).

A secondary service that is related to the teeth or structures directly supporting the teeth unless it is incident to and an integral part of a covered primary service that is necessary to treat a nondental condition (e.g., tumor removal) and it is performed at the same time as the covered primary service and by the same physician/dentist. In those cases in which these requirements are met and the secondary services are covered, Medicare does not make payment for the cost of dental appliances, such as dentures, even though the covered service resulted in the need for the teeth to be replaced, the cost of preparing the mouth for dentures, or the cost of directly repairing teeth or structures directly supporting teeth (e.g., alveolar process).

Exceptions to Services Excluded

Exceptions include the extraction of teeth to prepare the jaw for radiation treatment of neoplastic disease, as well as an oral or dental examination performed on an inpatient basis as part of comprehensive workup prior to renal transplant surgery or performed in a rural health clinic/FQHC prior to a heart valve replacement.

SOURCE: CMS, 2010a.

posed and, in some instances, used to provide some oral health care. The extent to which all of these professionals interact can vary greatly.

The surgeon general’s 2000 report expressed concerns about

a declining dentist-to population ratio, an inequitable distribution of oral health care professionals, a low number of underrepresented minorities applying to dental school, the effects of the costs of dental education and graduation debt on decisions to pursue a career in dentistry, the type and location of practice upon graduation, current and expected shortages in personnel for dental school faculties and oral health research, and an evolving curriculum with an ever-expanding knowledge base. (HHS, 2000)

Unfortunately, these concerns continue today.

The following section will focus on the traditional dental workforce in terms of its demographic profile, basic education and training, and racial

and ethnic diversity, as well as the role of new and emerging members of the dental team. Later sections in this chapter will describe the roles and skills of other types of health care professionals (e.g., nurses, physicians) in the provision of oral health care.

Basic Demographics

The adequacy of the current supply of oral health professionals, both in terms of its numbers and skills, is difficult to assess for a variety of reasons related to changes in employment status, differing measures (e.g., licensed vs. active professionals), the holding of more than one position per worker, part-time employment, and the presence of multiple job titles. Predicting the need for specific types of practitioners is always difficult because many factors can affect the need and demand for oral health care (Brown, 2005; Guthrie et al., 2009). For example, improvements in oral health of the population might limit future demand for restorative care.

While it is debatable whether the number of professionals is adequate, it is more certain that the oral health workforce is not well distributed, with distinct areas showing significant needs (Hart-Hester and Thomas, 2003; Mertz and Grumbach, 2001; Saman et al., 2010). Even with a sufficient supply, geographic maldistribution could still persist (Wall and Brown, 2007). For example, even with financial incentives such as loan repayment, dentists willing to locate in rural areas might be unable to sustain a practice in these locations (Allison and Manski, 2007). More attention may be needed to where students are recruited from, as 57 percent of graduates report plans to return to work in their home states after graduation (Okwuje et al., 2010).

Job growth during the next decade is projected to be above average for all the dental professions, particularly for dental hygienists and dental assistants (see Table 3-3). In fact, dental hygienists rank twelfth on the list of the fastest-growing occupations (of all occupations) and fifth among occupations directly related to health care (see Table 3-4). Dental assistants rank fourteenth on the list of the fastest-growing occupations and sixth among occupations directly related to health care.

Dentists

Estimates of the number of dentists in the workforce vary significantly, likely due to how they are counted. As shown in Table 3-3, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates that dentists held approximately 141,900 jobs in 2008, 85 percent of which were in general dentistry. However, in 2007, the American Dental Association (ADA) estimated that there were 181,725 professionally active dentists; 79 percent were general dentists

TABLE 3-3

Employment of Dental Occupations, 2008 and Projected 2018

| Occupation | Number of Jobs | Percent Increase In Growth (%) | |

| 2008 | 2018 | ||

| Dentists | 141,900 | 164,000 | 16 |

| General dentists | 120,200 | 138,600 | 15 |

| Dental hygienists | 174,100 | 237,000 | 36 |

| Dental assistants | 295,300 | 400,900 | 36 |

| Dental laboratory technicians | 46,000 | 52,400 | 14 |

aThe Bureau of Labor Statistics calculates replacement needs based on estimates of job openings due to retirement or other reasons for permanently leaving an occupation.

bTotal job openings represent new positions due to both growth and replacement needs. Totals may not add precisely due to rounding.

SOURCES: BLS, 2010d,e,f,g.

(ADA, 2009d). The dentist-to-population ratio has remained relatively constant for nearly 20 years (about 60 dentists per 100,000 population) and is expected to decline in the coming decades (Wendling, 2010).

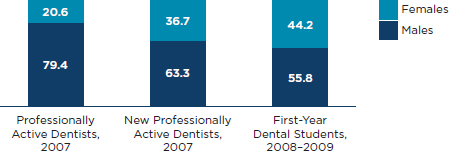

Among independent dentists in private practice, 43 percent are age 55 or older (ADA, 2009b). Like many other health care professions, concerns arise about replacement needs as these individuals retire. While most dentists are male, the proportion of female dentists is on the rise owing to the increased proportion of female dentists among younger dentists (see Figure 3-2). However, while dentistry is becoming increasingly gender diverse, the racial and ethnic profile of dentists has shown little change (see later in this section for a discussion of the racial and ethnic diversity of dental professions). Dentists’ income can vary depending on the type of employment, ranging from an average total net income of about $114,000 for new employed dentists to over $350,000 for independent specialists (ADA, 2009c).

As discussed previously, professionally active dentists overwhelmingly work in the private practice setting (92 percent). Among the remaining dentists, occupations include7

![]()

7 Does not total 100 percent due to rounding.

• Dental school faculty/staff member (1.7 percent),

• Armed forces (0.9 percent),

• Graduate student/intern/resident (1.3 percent),

• Hospital staff dentist (0.4 percent),

• State or local government employee (0.8 percent),

• Other federal service (0.8 percent), and

• Other health/dental organization staff (1.0 percent) (ADA, 2009d).

Among 2009 dental school graduates, 48 percent planned to enter private practice immediately, while 30 percent planned to go on to advanced education (e.g., residency), 11 percent planned to go into some form of government service, and less that one-half of 1 percent planned to enter teaching, research, or administration; the remainder were “other/undecided” (Okwuje et al., 2010).

TABLE 3-4

Top 15 Fastest-Growing Occupations, 2008 and Projected 2018

| Occupation | Percent Change, 2008–2018 |

| Biomedical engineers | 72.0 |

| Network systems and data communications analysts | 53.4 |

| Home health aides | 50.0 |

| Personal and home care aides | 46.0 |

| Financial examiners | 41.2 |

| Medical scientists, except epidemiologists | 40.4 |

| Physician assistants | 39.0 |

| Skin care specialists | 37.9 |

| Biochemists and biophysicists | 37.4 |

| Athletic trainers | 37.0 |

| Physical therapist aides | 36.3 |

| Dental hygienists | 36.1 |

| Veterinary technologists and technicians | 35.8 |

| Dental assistants | 35.8 |

| Computer software engineers, applications | 34.0 |

SOURCE: BLS, 2010c.

FIGURE 3-2

Percentage distribution of dentists by gender.

SOURCES: ADA, 2009d, 2010a.

Dental Hygienists

The dental hygiene profession began almost a century ago when a dentist trained his assistant to assist in preventive dental services (University of Bridgeport, 1998). Since then, dental hygiene has evolved to a licensed health care profession; dental hygienists, in concert with dentists, provide “preventive, educational, and therapeutic services supporting total health for the control of oral diseases and the promotion of oral health” (ADHA, 2010). In private dental practice, dental hygienists’ work is generally billed under the dentist’s provider number.

Dental hygienists are virtually all female (99 percent) (ADHA, 2009b). This is not changing dramatically: in 2008, only 2.8 percent of graduates of dental hygiene programs were male (ADA, 2009a). The mean age of dental hygienists is about 44 years of age (ADHA, 2009b), which, like dentists, may lend to concerns about the numbers nearing retirement. Dental hygienists are primarily employed in private dental practices but may also work in educational institutions and in public health settings such as school-based clinics, prisons, long-term care, and other institutional care facilities (ADHA, 2009b). In 2008, dental hygienists held about 174,100 jobs, with a median annual wage of about $66,500 (BLS, 2010e).8 Nearly 30 percent of dental hygienists do not receive any benefits (ADHA, 2009b).

In spite of BLS projections for a 36 percent growth in the employment of dental hygienists between 2008 and 2018 (see Table 3-4), the dental hygiene workforce may also be experiencing challenges due to geographic maldistribution. For example, a 2009 survey of dental hygienists showed that 68 percent of respondents reported finding employment was somewhat or very difficult in their geographic area (up from 31 percent in 2007), and

![]()

8 Because dental hygienists may hold more than one job, this is an overestimate of the number of practicing dental hygienists.

of these, 80 percent felt that there were too many hygienists living in the area (ADHA, 2009a,b).

Dental Assistants

Dental assistants primarily work in a clinical capacity, but other roles include administrative positions, practice management, and education (McDonough, 2007). Most dental assistants work in private practices and as assistants to general dentists, but many dental assistants work in specialty practices. Across the country, there are different job titles and categories for dental assistants in different states (ADAA/DANB Alliance, 2005). The BLS estimates that dental assistants held 295,000 jobs in 2008, with a median annual wage of about $32,000 (BLS, 2010d). Like dental hygienists, dental assistants are nearly all female (McDonough, 2007). Expanded function dental assistants (EFDAs) may perform some limited restorative functions under the supervision of a dentist (Skillman et al., 2010). Both the U.S. Army Dental Command and the Indian Health Service have programs to train and employ EFDAs (IHS, 2011; Luciano et al., 2006). While the title of EFDA is commonly used to describe all dental assistants who can perform extended duties, there are many other titles given to dental assistants with expanded duties (e.g., expanded duties dental assistant, advanced dental assistant, registered restorative assistant in extended functions), and many states permit dental assistants to perform specific extended functions (e.g., coronal polishing, administration or monitoring of sedation, pit and fissure sealants) (DANB, 2007). In fact, some states permit certified dental assistants to act at the level of an EFDA, even though titles such as certified dental assistant or registered dental assistant are used (DANB, 2007). As stated by the Dental Assistant National Board, “without a single, nationally-accepted set of guidelines that govern the practice of dental assisting in the country, it is difficult to execute a concise overview” of the profession (DANB, 2007).

Dental Laboratory Technicians

In 2008, dental laboratory technicians (or “dental technicians”) held about 46,000 jobs in 2008 with a median annual wage of about $34,000 (BLS, 2010g). Dental technicians work in a variety of settings, including dentists’ offices, their own private businesses, or small privately owned offices. Among all students enrolled during the 2008–2009 academic year, 40 percent were age 23 and younger and slightly more than half were female (ADA, 2009a).

Education and Training

Prior to the 20th century, dental and allied dental education occurred through apprenticeships and training in proprietary schools (Haden et al., 2001). The education of dental professionals evolved and formalized over time to take place in a variety of locations, including dental schools, 4-year colleges and universities, community colleges, and technical schools. The ADA’s Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) accredits predoctoral dental education programs; programs for dental hygienists, dental assistants, and dental laboratory technicians; and advanced dental educational programs (i.e., residencies) (Department of Education, 2010). While the number of programs is increasing, faculty recruitment, especially for dental schools and dental hygiene programs, is a persistent problem; this is often due to low salary (ADHA, 2006; Chmar et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2008). In addition, several efforts have emphasized the need to revise the way that dental students are educated and trained, including the need to provide care in a more patient-centered fashion, as well as for students to gain more clinical experiences in the community setting (Cohen et al., 1985; Formicola et al., 1999, 2006; HHS, 2010; IOM, 1995; Lamster et al., 2008). More effort is also needed to improve the health literacy and cultural competency of students.

The sections below provide some highlights as to the overall education and training of the dental professions. Chapter 4 provides more information on the role of HHS in education and training.

Dentists

U.S. dental schools typically offer a 4-year curriculum; students take 2 years of predominantly basic science classes followed by 2 years of predominantly clinical experience, after which they are awarded either a Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD), or a Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS). The number of dental schools in the United States is increasing, and more dentists are being produced. In 2009, there were 57 dental schools, of which 37 were public, 16 were private, and 4 were private, state-related institutions (ADA, 2010a). At that time, 8 new dental schools were in various stages of development (Guthrie et al., 2009). About 4,800 dentists graduate each year (ADA, 2010a). In 1999, there were 55 dental schools that graduated about 4,100 dentists annually (ADA, 2010a.)

The cost of dental education is a barrier to entry, especially for low-income and underrepresented minority students (IOM, 2004; Sullivan Commission, 2004; Walker et al., 2008). In 2008–2009, the average annual tuition for dental schools was $27,961 for state residents and $41,561 for nonresidents, similar to the tuition for medical students (AAMC, 2011;

ADA, 2010a); the difference is significant considering that many states do not have a single dental school. As this problem exists for several professions, the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education created the Professional Student Exchange Program in which students from certain states may receive assistance to attend health professional schools (including dental schools) in other states (WICHE, 2011). There is also great variation between public and private institutions.

In 2009, average dental education debt was $164,000, and 77 percent of graduates had at least $100,000 in debt (Okwuje et al., 2010). Comparatively, the average educational debt for medical school graduates in 2009 was approximately $156,000, and 79 percent of graduates had at least $100,000 in debt (AMA, 2011). Debt among dental graduates varies widely; those with higher levels of debt are more likely to enter private practice immediately upon graduation and less likely to pursue advanced education as compared to those with no debt (Okwuje et al., 2010).

Dentists have the option of postgraduate education that provides further training in general dentistry or one of the nine recognized specialty areas. In 2008–2009, there were 723 specialty and postdoctoral general dentistry programs in the United States, including dental residencies and fellowship programs (ADA, 2010b). Currently, about 30 percent of graduating dental students plan to pursue postgraduate training (Okwuje et al., 2010). In the 2008–2009 academic year, there were nearly more than 44,500 applications9 for residency programs slots and about 3,000 first-year enrollees (ADA, 2010b).

Dental Hygienists

In the 2008–2009 academic year, there were 301 dental hygiene education programs accredited by CODA (ADA, 2009a). Most of these programs award associate degrees (82 percent), but others award baccalaureate degrees, diplomas, and certificates (ADA, 2009a). In 2008, there were about 6,700 dental hygiene graduates. In the early years of the profession, dental hygiene education programs were often colocated with dental education programs in schools of dentistry (Haden et al., 2001). Today, about two-thirds of dental hygiene education programs are located in community, junior, and technical colleges (ADHA, 2006), which may decrease the amount of interaction between dentists and dental hygienists during their training, and therefore not prepare them to work as a team. Annual tuition can vary widely. For example, community colleges have an average annual tuition of $3,154, while the average annual tuition for programs colocated with dentals schools is $12,659 (ADA, 2009a). While the educational admissions

![]()

9 This reflects the number of applications and not the unique number of applicants.

requirements for dental hygiene education programs vary widely, more than 80 percent of first-year students have completed at least 2 years of college (ADA, 2009a). Faculty in dental hygiene education programs are mostly dental hygienists (76 percent), and 21 percent are dentists (ADA, 2009a).

Dental Assistants

Dental assistants are trained on the job or in formal education programs. Education programs in dental assisting may be located in postsecondary institutions that are accredited by CODA, postsecondary institutions that are not accredited, high schools, vocational programs, and technical schools (ADAA/DANB Alliance, 2005). Dental assistants may also be trained on the job by their employers. Considering the numerous alternate pathways to working in dental assisting and the variability in state licensure and certification practices, as described previously, it is difficult to generalize a description of the workforce as a whole or to assess the impact of the various training alternatives (ADAA/DANB Alliance, 2005; Neumann, 2004). Little is known about the wide variety of programs that are not accredited by CODA.

In 2008–2009, CODA accredited 273 dental assisting programs, almost all of which (87 percent) were in public institutions (ADA, 2009a). Average cost for tuition and fees in a CODA-accredited dental assisting program in the 2008–2009 academic year for in-district students was $6,791 (ADA, 2009a). Among students enrolled in CODA-accredited dental assisting programs in the 2008–2009 academic year, 63 percent were age 23 and under, and less than 5 percent were male. In 2008, there were 6,110 graduates from CODA-accredited programs (ADA, 2009a).

Virtually all CODA-accredited programs require a high school diploma (or even higher level of education) for admission (ADA, 2009a). Most CODA-accredited programs are 1 year in length leading to a certificate or diploma. However, a few have a 2-year curriculum resulting in an associate degree. About 14 percent of faculty in CODA-accredited programs are dentists, 70 percent are dental assistants, and 28 percent are dental hygienists (ADA, 2009a).10

Dental Laboratory Technicians

There are no formal education or training requirements for dental technicians, and most learn required skills through on-the-job training; however, some formal programs exist in universities, community and junior

![]()

10 Some faculty members reported more than one discipline, so these numbers do not total 100 percent.

colleges, vocational schools, and the military (BLS, 2010g). In the 2008– 2009 academic year, there were 20 CODA-accredited programs (ADA, 2009a). Virtually all faculty (91 percent) are dental laboratory technicians (ADA, 2009a). Most accredited programs last 2 years, and 13 confer an associate’s degree. In the 5-year period from 2004–2009, applications to these programs decreased by nearly 13 percent (ADA, 2009a). Average total tuition and fees range from $7,838 for in-district students to $18,214 for out-of-state students (ADA, 2009a). In 2008, there were 234 total graduates from accredited dental laboratory technology programs (ADA, 2009a).

Racial and Ethnic Diversity

The racial and ethnic profile of the dental workforce is not representative of the overall population (see Table 3-5). While diversity among the dental professions students has increased in the previous decade (see Table 3-6), the numbers still are not significantly different. Evidence shows that a diverse health professions workforce (including race and ethnicity, gender, and geographic distribution) leads to improved access for underserved populations, greater patient satisfaction, and better communication (HRSA, 2006; IOM, 2004). Health care professionals from underrepresented minority (URM) populations, in part due to patient preference, often account for a disproportionate amount of the services provided to underserved populations (including both URM and low-income populations) (Brown et al., 2000; HRSA, 2006; IOM, 2003; Mitchell and Lassiter, 2006). For example, a 1996 survey by the ADA revealed that nearly 77 percent of white den-

TABLE 3-5

Dental Professions by Percentage of Race and Hispanic Ethnicity, 2000

| General Population | Dentists | Dental Hygienists | Dental Assistants | |

| Whitea | 75.1 | 82.8 | 90.9 | 75.8 |

| Black or African Americana | 12.3 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 5.6 |

| Asiana | 3.6 | 8.8 | 2.0 | 3.6 |

| Hispanic or Latino Origin | 12.5 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 12.6 |

aCategory excludes Hispanic origin.

SOURCES: U.S. Census Bureau, 2000, 2002.

TABLE 3-6

Percentage of Dental Professions School and Program Enrollment by Race and Hispanic Ethnicity, 2000–2001 and 2008–2009

| Enrolled Dental Students | Enrolled Dental Hygiene Students | Enrolled Dental Assistant Studentsa | ||||

| 2000–2001 | 2008–2009 | 2000–2001 | 2008–2009 | 2000–2001 | 2008–2009 | |

| White | 63.4 | 59.9 | 82.3 | 78.6 | 68.4 | 60.2 |

| Black | 4.8 | 5.8 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 12.5 | 15.1 |

| Asian | 24.8 | 23.4 | 4.6 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 4.8 |

| Hispanic | 5.3 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 7.3 | 9.7 | 11.1 |

aIncludes only dental assistant students enrolled in CODA-approved programs. Racial and ethnic diversity of entire dental assistant workforce may be different.

SOURCES: ADA, 2002, 2009a, 2010a.

tists’ patients were white, while 62 percent of African American dentists’ patients were African American and 27 percent were white (ADA, 1998). More recently, among dental students graduating in 2008, 80 percent of African American students and 75 percent of Hispanic students expected at least one-quarter of their patients would be from underserved racial and ethnic populations; nearly 37 percent of the African American students and 27 percent of the Hispanic students expected at least half their practice would come from these populations (Okwuje et al., 2009). In comparison, only 43.5 percent of white students expected at least one-quarter of their patients to come from underserved racial and ethnic populations, and only 6.5 percent expected at least half of their practice to be comprised from these populations (Okwuje et al., 2009). It is important to note that the recruitment of low-income students (regardless of race or ethnicity) may also be important in the future care of URM patients (Andersen et al., 2010).

Several factors complicate recruitment of underrepresented minorities into dentistry including lack of exposure to and knowledge of the dental profession, minimal opportunities for mentorship from dental professionals, and competition from other health professions for underrepresented minority students who are academically qualified (Haden et al., 2003).

Bridge and Pipeline Programs

Bridge and pipeline programs are two strategies used to attract and retain underrepresented minority, lower-income, and rural students to health care professions. Bridge programs primarily focus on elementary school

students through high school graduates while pipeline programs focus on undergraduate and preprofessional students. Both programs have a long history in health professions (e.g., dentistry, medicine, nursing, pharmacy) (Awé and Bauman, 2010; Brooks et al., 2002; Brunson et al., 2010; Cantor et al., 1998; Formicola et al., 2010; Grumbach and Chen, 2006; Hesser et al., 1996; Kim et al., 2009; Lewis, 1996; Rackley et al., 2003; Thomson et al., 2010).

Pipeline interventions for improving racial and ethnic diversity in the health professions in general have shown promise (HHS, 2009). In 2001, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, in collaboration with the California Endowment and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, created the initiative Pipeline, Profession, and Practice: Community-Based Dental Education,11 which ended in July 2010. This project provided much insight into strategies for successful implementation (Lavizzo-Mourey, 2010; Leviton, 2009). Overall, dental pipeline programs show promise, but gains to date have been small and individual programs have had variable results regarding the ultimate enrollment and retention of students, dependent upon the program’s characteristics (Andersen et al., 2005; Markel et al., 2008; Price et al., 2007; Thind et al., 2008; Veal et al., 2004). Moreover, it has yet to be determined whether these programs will have a long-term effect on increasing diversity in dentistry. Evidence suggests that pipeline programs require a sustained commitment by participating schools and sufficient resources to maintain momentum (Brunson et al., 2010; Thind et al., 2009).

One example of an effort to increase the diversity of the dental workforce is the ADA Career Guidance and Diversity Committee, which sponsors the Student Ambassador Program. In this program, ambassadors reach out to high school and college students regarding careers in dentistry (ADA, 2011b). Strategies include increasing collaborations between dental schools and college prehealth advisors, providing shadowing opportunities, and linking to existing career guidance programs.

New and Emerging Members of the Dental Team

Many health care professions have become embroiled over the creation of new types of practitioners as well as over the expansion of scope of practice for existing practitioners. Within the dental professions, efforts to define or expand scopes of practice for dental professionals have been plagued by a decades-long, contentious history (Dunning, 1958; Edelstein, 2010b; Fales, 1958; Hammons and Jamison, 1967, 1968; Hammons et al., 1971; Nash, 2009; Nash and Willard, 2010). Early experiments to have dental

![]()

11 For information on participating schools, funding levels, activities, accomplishments, and community partners, see the RWJF project website at: http://www.dentalpipeline.org.

hygiene students perform discrete restorative procedures indicated that the quality of the care provided by these students was equal to that of dental students, but follow-up studies were not performed amidst the concerns of organized dentistry for patient safety (Dunning, 1958; Garcia et al., 2010; Lobene and Kerr, 1979; Sisty et al., 1978). Dental therapists and dental nurses have been used internationally for decades (Ambrose et al., 1976; Gallagher and Wright, 2003; GAO, 2010; Nash and Nagel, 2005b; Nash et al., 2008; Pew Center on the States and National Academy for State Health Policy, 2009; Sun et al., 2010). In particular, New Zealand and Australia have used these dental professionals since the early 20th century. Suggestions to perform a demonstration of the New Zealand school dental nurse in the United States occurred as early as 1947 (Dunning, 1958), but they were not acted upon, again due to the concerns of dentists for patient safety.

The use of dental therapists to provide basic educational, preventive, and restorative services in the United States has been especially contentious. Recently, the Indian Health Service (IHS) has used dental therapists to perform specific functions in order to address oral health access difficulties for American Indian communities (Bolin, 2008; Fiset, 2005; Nash and Nagel, 2005a,b; Wetterhall et al., 2010). In 2003, the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium first sent several Alaskan students to New Zealand to train as dental therapists, and the consortium is currently working with the University of Washington to train these students in Alaska (DENTEX, 2010; Nash and Nagel, 2005b). The first assessment of dental therapists in the United States indicated there was no significant difference between treatment provided by dental therapists and treatment provided by dentists (Bolin, 2008). A more recent evaluation indicates that the care provided by dental therapists in the United States is both effective and acceptable to patients (Wetterhall et al., 2010). Further, residents of communities served by dental therapists report that access to care has improved. It is important to note the narrow scope of this evaluation in that the authors examined the implementation of the dental therapist model in just five practice sites. In addition, they noted: “We undertook this challenging effort knowing that there are few, if any, widely accepted, evidence-based standards for assessing dental practice performance. Further, for the logical comparison group—that is, dentists in private practice—there are virtually no data for any of the outcomes that we undertook to observe and measure” (Wetterhall et al., 2010).

Aside from the dental therapist, several other workforce models have been recently proposed to either introduce new types of professionals or expand the scope of work of existing professionals. For example, in 2009, the Minnesota legislature approved the certification of a master’s

level “advanced dental therapist”12 to work in remote consultation with a dentist and provide some restorative procedures (GAO, 2010). The Community Dental Health Coordinator (CDHC), developed by the ADA, would provide oral health education and some limited preventive services under the supervision of a dentist (GAO, 2010; Pew Center on the States and National Academy for State Health Policy, 2009). The registered dental hygienist in alternative practice (RDHAP) started as a pilot project in the 1970s; the RDHAP is licensed (only in California) to provide care directly to patients but must have a documented relationship with a dentist for referral, consultation, and emergencies (Mertz and Glassman, 2011).

All of these new and emerging members of the dental team (and several others) have been targeted to reach populations that for a variety of reasons (e.g., transportation, geographic location, dental coverage issues) have difficulty accessing care. While there are differences, all depend on the practitioner being part of a larger health care team (Garcia et al., 2010). Many of these models remain controversial, with some arguing for their ability to increase access, and others voicing concerns for patient safety and the quality of care provided by these practitioners (ADA, 2007; AGD, 2008; Edelstein, 2010b; GDA, 2010; Pew Center on the States and National Academy for State Health Policy, 2009).

Lessons from Other Health Care Professions

Concerns have been raised in other fields when new types of practitioners were being developed or when existing professionals sought to extend their scopes of practice (Carson-Smith and Minarik, 2007; Daly, 2006; Huijbregts, 2007; RCHWS, 2003; Wing et al., 2004). While nurse practitioners and physician assistants are largely seen as well-accepted members of the health care team, their development was also resisted, and extension of their scopes of practice remains a sensitive issue. Professional tensions typically center around the quality of care provided by individuals with less training, but in many cases, evidence has not supported this. Advanced practice nurses are often involved in high-risk procedures such as childbirth and the administration of anesthesia, yet the evidence base continues to grow that the quality of their care is similar to that of physicians. For example, studies on certified nurse midwives have shown good maternal outcomes and cost savings in comparison with obstetricians (MacDorman and Singh, 1998; Oakley et al., 1996; Rosenblatt et al., 1997). Certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), like many nonphysician health care professionals, are an important source of care in rural populations: CRNAs are the sole providers of anesthesia in more than two-thirds of

![]()

12 2009 Minn. Laws Ch. 95, Art. 3.

all rural hospitals (AANA, 2011). In 2001, CMS ruled that states could opt out of requirements for physician supervision of CRNAs, a decision that was opposed by anesthesiologists due to concerns for quality of care (Dulisse and Cromwell, 2010). However, a study of the time period from 1996 until 2005 revealed that there was an increase in the number of procedures performed by CRNAs, but there was no concomittant increase in adverse events (Dulisse and Cromwell, 2010). These examples provide some evidence on the ability to use nonphysician health care professionals to provide quality care in some situations.

Conclusions

While dentists continue to raise concerns for the quality of care provided by individuals (apart from dentists) who might perform restorative care, there is a lack of evidence documenting poorer quality of the services performed by these individuals or poorer outcomes resulting from their care. There are many studies of the safety and quality of dental therapists and dental nurses around the world, but these models occur in different systems of care delivery and financing. Evaluations in the United States to date have been limited, and it is nearly impossible to compare their quality to that of existing dental professionals, since little evidence exists on the quality of care provided by traditional dental practitioners (see a discussion of quality of care later in this chapter). The committee considered the concerns raised by dentists, the unresolved needs of certain segments of the population (e.g., vulnerable and underserved populations), international evidence, and the experiences seen in developing new roles and responsibilities among other health care professions. In addition, the committee recognizes that there is little evidence to indicate which route would be best—developing new types of providers or expanding the scope of existing dental professionals. Due to the variety of challenges, the committee concludes that the exploration of new workforce models (including both new types of dental professionals as well as expansion of the role of existing professionals) is one part of a complex solution to improving oral health care. There may, in fact, be roles for different models depending on the needs of the population and sites of care. Without further research and evaluation, with monitoring for any concerns about the quality of care, better workforce models cannot be developed. Regardless of state laws, many factors will influence the ultimate success of new workforce models, including the support of dentists, the support of state Medicaid agencies, and a viable mechanism for paying the new types of practitioners (Nolan et al., 2003).

THE NONDENTAL ORAL HEALTH WORKFORCE

As oral health has increasingly become recognized as integral to overall health, nondental health care professionals have become increasingly involved in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of oral diseases. Studies show that training primary care clinicians in oral health leads to their increased ability to recognize oral disease and may help to increase their referrals to dentists (Dela Cruz et al., 2004; Mouradian et al., 2003; Pierce et al., 2002). In addition, practice changes resulting from this training can lead to increased access to preventive services and decreased dental disease (Chu et al., 2007; Douglass et al., 2009b; Kressin et al., 2009; Rozier et al., 2010). As discussed in Chapter 2, all types of health care professionals need improvements in their oral health literacy skills. In order to do so, educational programs will need to adapt curricula not only to teach basic oral health knowledge but also to impart a greater understanding of the importance of oral health to their individual disciplines. This section considers the education, training, and potential role of several nondental health care professions in the oral health care of the nation. At the end of the section, the role of nondental health care professionals as a whole in the delivery of preventive services for oral health is discussed.

Physicians

The need for physicians to learn about oral health has been recognized for nearly a century (Gies, 1926). Today, many physicians still do not receive education or training in oral health either during medical school, during residency training, or in continuing education programs (Krol, 2010; Mouradian et al., 2003). In addition, the breadth and depth of existing education and training efforts is highly variable (Douglass et al., 2009a; Ferullo et al., 2011). Even though many physicians recognize the importance of oral health (including their own role), they often do not feel prepared to provide oral health care. (See a discussion in Chapter 2 regarding health care professionals’ knowledge of oral health.) Dentists also express some hesitation about involving physicians in oral health care; while a large majority of directors of advanced general dentistry residencies supported physician inclusion of routine dental assessments (87.1 percent) and prevention counseling (83.3 percent) in well-child care, less than a third (31.2 percent) supported physicians applying fluoride varnish (Raybould et al., 2009).

Medical Schools

Very few medical schools include curriculum on oral health, despite the presence of oral health topics on medical licensing exams (Ferullo et

al., 2011; Krol, 2004; Mouradian et al., 2005; USMLE, 2010a,b). A recent survey indicated that almost 70 percent of medical schools include 4 hours or less of oral health in their curriculum; this includes the more than 10 percent of schools that have no oral health curriculum hours at all (Ferullo et al., 2011). The most frequently covered oral health topics include oral cancer, oral anatomy, and oral health and overall health; fewer than 50 percent of schools that teach oral health cover the risks of dental caries (Ferullo et al., 2011).

In 2004, the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation funded a 3-year grant to examine dental education, New Models of Dental Education (Formicola et al., 2005; Machen, 2008). As part of the project, three panels were convened to discuss different aspects of oral health education and each produced a report (Johnson et al., 2008; Lamster et al., 2008; Mouradian et al., 2008). One panel produced the report, Curriculum and Clinical Training in Oral Health for Physicians and Dentists, which emphasized the role for physicians in the identification and referral of patients with oral health needs (Mouradian et al., 2008). Subsequently, the American Association of Medical Colleges published learning objectives for oral health (AAMC, 2008). Courses that have incorporated these objectives have significantly increased students knowledge of oral health topics, even in a short time period (Silk et al., 2009). One medical school at the forefront of oral health education, the University of Washington Medical School, created and has started to implement a comprehensive oral health curriculum for medical students; results show students have more confidence in identification of oral disease and attitudes toward oral health care improved (Mouradian, 2010; Mouradian et al., 2005, 2006).

Pediatricians

A 2000 national survey of pediatricians found that more than 90 percent believed they had an important role in the recognition of oral diseases and the provision of counseling regarding the prevention of caries, and three-quarters expressed interest in the application of fluoride varnish in their practices (Lewis et al., 2000). However, half reported no oral health training in either medical school or residency. A 2006 survey found that two-thirds of graduating pediatrics residents thought they should be performing oral health assessments on their patients, but only about one-third of pediatrics residents receive any oral health training during their residencies, and of those that do, two-thirds get less than 3 hours of training. (Caspary et al., 2008). Only about 14 percent had clinical observation time with a dentist.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the professional society for general pediatrics, has developed explicit educational guidelines for oral

health training in pediatric residency (AAP, 2011c). In addition, the pediatric board exam has questions about oral health (ABP, 2009). However, the residency review committee for pediatrics has not yet identified oral health as a required topic for pediatric residencies.

Family Medicine Physicians

Family medicine has taken a number of steps to incorporate oral health into residency curriculum. The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Group on Oral Health published an oral health curriculum for family medicine in 2005 (it was updated in 2008), and the residency review committee for family medicine residencies added oral health as a requirement in 2006 (ACGME, 2007; Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Group on Oral Health, 2011). Yet, a recent survey showed only three-fourths of the residency directors knew of the oral health requirement, and only about two-thirds of the programs were actually including oral health content, with the most common training time being 2 hours per year (Douglass et al., 2009a).

Internal Medicine Physicians

Of the primary care specialties, internal medicine has done the least to incorporate oral health. Oral health education is not a requirement for internal medicine residencies, although the geriatrics subspecialty requires education in prevention of oral diseases, and the sleep medicine subspecialty requires residents to have experience receiving consults from oral maxillofacial surgeons (ACGME, 2008, 2009a,b). No specific curricula exist to educate internal medicine residents or physicians in oral health. In a survey of internal medicine trainees, 90 percent reported receiving no training on periodontal disease during medical school, and 23 percent said they never referred patients to dentists (Quijano et al., 2010).

Nurses

The nursing workforce is the largest workforce of health professionals in the nation, with 3.1 million registered nurses including over 141,000 nurse practitioners (NPs) (ANA, 2011a, 2011b). In a recent “call to action” to the nursing profession, Clemmens and Kerr (2008) noted that “oral health has not been a high nursing priority in the past” and urged the profession to “increase nursing’s awareness, knowledge, and skill about the significance that oral health holds.” However, as with other nondental health care professions, the training of nurses in oral health and hygiene is highly variable and often inadequate (Jablonski, 2010).

NPs in particular may have an important role to play in oral health

care. A recent study found that “substantial parallels exist in the education and practice of dentists and [NPs] including basic, social, and some clinical science education, practice models, research synergies, and community service” (Spielman et al., 2005). NPs have been defined as primary care providers (IOM, 1996) and can see patients independently and perform histories and physicals, perform lab tests, and diagnose and treat both acute and chronic conditions. NPs emphasize health promotion and disease prevention and especially focus on the health of individuals in the context of their families and communities. NPs commonly practice in rural areas and health professional shortage areas, and the growth of the profession, in part, is due to their role in caring for underserved populations (Grumbach et al., 2003; Harper and Johnson, 1998). As such, they may serve as a frontline screening source for oral diseases. NPs have been shown to provide high-quality care, be cost-effective, have high levels of patient satisfaction with their care, and contribute to increased productivity (Budzi et al., 2010; Hooker et al., 2005; Mezey et al., 2005; Todd et al., 2004).

Criteria set by the National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education (2008) do not delineate any specific competencies for oral health. In 2006, the Arizona School of Health Sciences and the Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health developed a set of proposed oral health competencies for nurse practitioners and physician assistants (PAs) (Danielsen et al., 2006). As shown in Table 3-7, a subsequent survey of NPs and PAs revealed that many do not feel prepared for some of these basic competencies.

In addition to NPs, there are more than 3 million direct-care workers (e.g., nurse aides) who work in places where dental professionals typically do not provide care (e.g., assisted living facilities, home health agencies) (PHI, 2010). These nursing personnel also have the opportunity to be involved in the detection of oral diseases. In nursing home settings, certified nursing assistants are responsible for the provision of oral hygiene care for

TABLE 3-7

Perceived Competence of Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants (Percent)

| Nurse Practitioners | Physician Assistants | |

| Can perform an oral exam | 43 | 53 |

| Can recognize oral symptoms of systemic disease | 22 | 34 |

| Can discern “obvious pathology and conditions of the oral cavity” | 40 | 63 |

SOURCE: Danielsen et al., 2006.

residents, but they are often unprepared for this task and make it a low priority (Chalmers, 1996; Coleman and Watson, 2006; Jablonski et al., 2009).

Pharmacists

As health care professionals in community settings, the role of the pharmacist has expanded over time from merely dispensing medications to being an important partner with other health care professionals. Pharmacists are often involved in health promotion and disease prevention activities such as public health education, health screenings, and the provision of vaccines. In 2008, pharmacists held almost 270,000 jobs; about 65 percent worked in retail settings, and 22 percent worked in hospitals (BLS, 2009a). The BLS notes a likely increase in the need for pharmacists to provide services in settings such as doctors’ offices and nursing facilities as well as to increasingly offer patient care services, such as the administration of vaccines (BLS, 2009a).

Regarding oral health specifically, customers may approach pharmacists regarding the treatment of oral health conditions such as mouth ulcers, cold sores, and persistent pain (Cohen et al., 2009; Macleod et al., 2003; Sowter and Raynor, 1997; Weinberg and Maloney, 2007). Pharmacists can have an important role in the management and treatment of oral disease such as through education on selection and use of daily oral hygiene products as well as referrals to dentists as necessary. Pharmacists could also monitor the prescription of dietary fluoride supplements, especially as it might relate to the status of that community’s water fluoridation. No formal assessment has been done to evaluate the extent and depth of education and instruction that pharmacy students receive regarding oral health.

Physician Assistants

As primary care providers, PAs also have great opportunities and responsibilities to be involved in oral health care (Berg and Coniglio, 2006; Danielsen et al., 2006). PAs work under the supervision of a physician, but they can often work apart from the physician’s direct presence and can prescribe medications and bill for health care services. The BLS projects the PA profession to be the seventh fastest-growing occupation between 2008 and 2018 (see Table 3-4). In 2008, PAs held about 74,800 jobs; more than half of these jobs were located in physicians’ offices, and about one-quarter were in hospitals (BLS, 2009b).

About half of PAs work in primary care (Brugna et al., 2007; Hooker and Berlin, 2002). Like NPs, PAs are an especially important source of care for rural communities, for low-income and minority populations, and in health professional shortage areas (Grumbach et al., 2003), and they have

been shown to provide quality and cost-effective care (Ackermann and Kemle, 1998; Brugna et al., 2007; Jones and Cawley, 1994).

Very little is known about the extent of oral health education in the PA curricula. As in nurse practitioner programs, standards set by the Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant (ARC-PA, 2010) do not delineate any specific competencies for oral health. In the previously mentioned survey performed by the Arizona School of Health Sciences and the Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health, many PAs feel unprepared for some basic oral health competencies (see Table 3-7). Interestingly, that survey showed that 10 percent of PAs did not think it was important for them to understand what the various dental specialties could do for their patients (compared to 2 percent of nurse practitioners) (Danielsen et al., 2006). A recent survey of PA program directors found “over 75 percent believed that dental disease prevention should be addressed in PA education, yet only 21 percent of programs actually did so” (Jacques et al., 2010). The number of curriculum hours dedicated to oral health ranged from 0 to 14 hours, with an average of 3.6 hours.

The Role of Nondental Health Care Professionals in Preventive Care

One solution for improving access to preventive care for oral health, especially for children, has been to expand the use of nondental health care professionals (Douglass et al., 2009b; Hallas and Shelley, 2009; Okunseri et al., 2009). Nondental health care professionals can incorporate oral health into their routine exams and wellness visits with basic risk assessments, oral exams, anticipatory guidance, and the provision of basic preventive services (Cantrell, 2008; Riter et al., 2008). The application of fluoride varnish is a prime example for the potential expanded role of nondental health care professionals. Fluoride varnish is increasingly being applied by nondental health care professionals and in community-based settings (AAP, 2011b; ASTDD, 2007). In spite of evidence on the effectiveness of fluoride varnish (see Chapter 2), it is not approved by the FDA for its use in the prevention of dental caries (ASTDD, 2007), which may deter some health care professionals from using it for this purpose.

In the past, nondental health care professionals could not be reimbursed for preventive care in oral health, but this is changing. As of 2010, 39 state Medicaid programs reimbursed primary medical care providers for preventive oral health services, 2 approved such reimbursement but did not have funding, and another 3 allowed reimbursement under certain circumstances (AAP, 2010). This is an increase from 2008, when only 25 states reimbursed physicians for these types of services, and 2009, when 34 states did so (Cantrell, 2008, 2009). In addition, some states also reimburse NPs and PAs for these services (Cantrell, 2008). The three types of services

typically reimbursed include oral examination, screening, and risk assessment; anticipatory guidance and caregiver education; and application of fluoride varnish (Cantrell, 2009). In 2009, 25 states required the health care professionals undergo training before they could be reimbursed (Cantrell, 2009). Aside from lack of reimbursement, other barriers to engaging nondental health care professionals in preventive care (both for oral health as well as other health conditions) can include the lack of familiarity with oral health issues, lack of confidence in their skills, skepticism on the efficacy of preventive services, and inadequate time in the patient visit (Lewis et al., 2000; Rozier et al., 2003; Sanchez et al., 1997).

Several individual state-based initiatives have arisen to help improve nondental health care professionals’ involvement in providing basic preventive services for oral health. One well-known example is North Carolina’s Into the Mouths of Babes (IMB) which targets children up to age 3 (Rozier et al., 2003, 2010). IMB stemmed from earlier work in the 1990s where poor oral health was identified as one of the most serious problems for children and their families in the Appalachian region of the state. With support from the North Carolina Medicaid program, CMS, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, lessons learned from that work led to the statewide demonstration of IMB in 2001. The project aims to improve practitioners’ oral health knowledge, incorporate caregiver counseling and fluoride varnish application into primary care practices, and increase screenings and dental referrals for children with oral diseases or are at risk for diseases (Close et al., 2010). Reimbursement is provided for up to 6 visits for children up to age 3. Between 2001 and 2002, nearly 1,600 nondental health care professionals were trained (Rozier et al., 2003). About half of the participants were pediatricians or family physicians and another one-third were registered nurses; others included PAs, NPs, and a variety of other health care professionals. In 2006, almost one-third of all well-child visits for this age group included preventive care for oral health (Rozier et al., 2010). In 2009, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services reported a ten-fold increase in the number of preventive procedures since the inception of IMB (NC Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Program successes have been attributed to a broad-based, collaborative coalition, support from the professions themselves, an active effort to improve awareness about oral diseases, and adequate resources (Rozier et al., 2003). A recent survey of participants in the program identified some of the barriers to success, including difficulty integrating the services into practices (reported by 42 percent), difficulty in applying fluoride varnish (29 percent), reluctance of other office personnel (26 percent), and difficulty in making dental referrals (21 percent) (Close et al., 2010). In order to better integrate the application of fluoride varnish into primary care setting, providers may

need to look to the model of immunization as an example of successfully integrating the delivery of preventive services in these settings.