5

Socioecological Perspectives: The Individual Level

|

Key Messages Noted by Participants

|

The socioecological model is a framework allowing for integration of the multiple elements of a person’s life. These elements occur at different levels, including the individual level, the family and household level, the environmental level, and the institutional level. On the morning of the second day of the workshop, speakers examined the link between food insecurity and obesity from each of these perspectives.

A challenge for the socioecological model is moving beyond association to causation, said Christine Olson, who moderated the session that focused on the individual. For example, there is little doubt among researchers that there is an association between food insecurity and obesity for adult women, but are the two causally related, and if so in which direction do the arrows of causation run? “Actually they probably run both ways,” said Olson, “and sorting through the amount of a relationship accounted for by the arrows in each direction is an important thing to do.” Similarly, it is important to understand what the mediators and moderators of a relationship are if a relationship does exist. Longitudinal studies are especially good for examining these types of questions.

SHORT-TERM DYNAMICS

Colleen Heflin, associate professor at the Truman School of Public Affairs at the University of Missouri, addressed two questions in her presentation:

-

How are obesity and weight change related to the risk of food insecurity in adulthood?

-

How is food insecurity related to the risk of obesity and weight gain in adults?

Of course, individuals are embedded within families, environments, and institutions, all of which interact. Nevertheless, it is possible to try to isolate the factors affecting the individual. In particular, what are the mechanisms that connect food insecurity and obesity, and how do these operate at the level of the individual?

Obesity and the Labor Market

The first possibility is that obesity may adversely affect labor market outcomes. This could occur because of the existence of weight-related health problems, or it could occur directly as a result of employers, coworkers, and clients discriminating against individuals with high weight. The reduction of labor market income then could increase the risk of poverty and food insecurity.

Considerable evidence from both the United States and Europe chronicles the relationship between obesity and health problems, including diabetes, hypertension, and osteoarthritis, said Heflin. For example, the Framingham Heart Study has shown that obesity in adulthood is associated with increased risk of disability throughout life and increased limitations of daily activity.

In addition, a large number of studies indicate that individuals with health problems have poorer labor market outcomes. Individuals with obesity-related health outcomes may not be able to perform certain job functions or may be limited in the amount of a function they can perform. They also may have a lower probability of being employed or may receive a lower wage.

Furthermore, studies have found that weight-related discrimination occurs at every stage of employment. When the weight of a job application is randomly assigned in a description, picture, or videotape but all other background information remains constant, the overweight applicant is consistently judged to be less qualified than an applicant with the same qualifications but a lower weight (Roehling, 1999). In a study of applicants for a sales job, participants rated the overweight applicants as lacking self-discipline, having lower supervisory potential, having poor personal hygiene, and lacking in professional appearance (Puhl and Brownell, 2001). Overweight applicants also are judged less desirable as supervisors and coworkers (Roehling, 1999).

Another set of evidence in this area comes from legal cases that have been brought alleging weight as a factor in a job dismissal or suspension of employment. In a Gallup poll (2003), 20 percent of respondents freely admitted that they would be less likely to hire an applicant if the applicant was overweight. “There is a substantial amount of evidence indicating that obesity and weight gain might be related to labor market outcomes,” Heflin concluded.

Recent research supports the conclusion that obesity is associated with poorer labor market outcomes. A study by Lindeboom et al. (2010) that followed 17,000 individuals born in Great Britain in a single week in March 1958 found that obesity at age 33 was associated with lower employment probabilities for both men and women. Tunceli et al. (2006) found that obesity was marginally associated with reduced employment for both men and women after adjusting for baseline sociodemographic characteristics, smoking status, exercise, and self-reported health.

However, the evidence for lower incomes among overweight employees is considerably weaker. Lindeboom et al. (2009) found evidence of a wage penalty for women only, not for men, and the evidence of a wage penalty for women is sensitive to modeling assumptions and identification strategies.

Other support for a link between obesity and labor market outcomes derives from longitudinal studies of women on welfare. Research by Cawley and Danziger (2005) found that white women who were morbidly obese were less likely to work, spent more time on welfare, and earned less. In this study, the effect size was large, on the order of returning to finish high school versus dropping out permanently. However, the same effect sizes were not found for African-American women. Morbidly obese African-American women in the study were found to spend more time on welfare, but they had no difference in labor market outcomes compared to African-American women of lower weight. This finding of a racial difference supports the earlier work of Cawley in which he reported that weight resulted in lower wages among whites but not among African-American women.

Food Insufficiency and Disadvantage

Causality also could run in the opposite direction, Heflin noted. In work that she has done with Mary Corcoran and Kristine Siefert using a longitudinal study of women on welfare, food insufficiency, which is slightly different from food security, was found to be highly correlated with various disadvantages (Corcoran et al., 1999). Women with food insufficiency report lower income, fewer work hours, more use of welfare, lower levels of formal education and job skills, poorer physical and mental health, higher occurrence of domestic violence, and less access to a car and a driver’s license. The data from this survey, which followed 750 women over a 7-year period, provide a unique opportunity to understand the short-term dynamics of food insufficiency. Roughly 20 percent of the sample reported food insufficiency during the five data collection waves, with considerable turnover in the population reporting food insufficiency. Although half of the sample never reported food insufficiency, half reported food insufficiency at least once over the 7 years, 21 percent reported food insufficiency only once, while 29 percent reported food insufficiency at multiple times.

Heflin et al. (2007) looked at possible explanations for changes in household food insufficiency. One possibility is that some households are better at managing scarce resources, which in a traditional framework might be related to a measure of human capital such as level of education. An alternative is that a mental health problem or domestic violence might interfere with the ability to budget resources rationally. A woman experiencing domestic violence may not be in control of financial resources or may be hoarding resources in order to escape. A household also could be responding to other demands, such as medical expenses or utilities, rather than food in the face of limited financial resources. Finally, food insufficiency may be related to changes in public assistance or the earned income tax credit, making it important to look at aggregate income.

Mental Health

Heflin’s research showed that the presence of individual constraints was supported only for mental health problems. Women who were undergoing transitions involving mental health problems were more likely to experience bouts of food insufficiency. Household income also was related to food insufficiency. However there was less support for the competing demands hypothesis, and factors such as human capital, work skills, and even the number of job losses were not related to transitions in food insufficiency.

“It looks a little bit like a puzzle,” Heflin concluded. “Obesity is related to lower labor force participation and wages potentially, but work transitions were not directly related to food insufficiency among low- income women. This suggests that perhaps there is a role for mental health.” A longitudinal study (Heflin et al., 2005) found that food insufficiency was significantly related to increases in depression among low-income women after controlling for household composition, income, neighborhood hazards, stressful life events, domestic violence, discrimination, and individual fixed effects. Further examination of this observation by Heflin and Ziliak (2008) looked at the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) as a modifier of the relationship between food insufficiency and mental health. SNAP could improve the income available to a household, and the support of the household could lead to an improvement in mental health. Yet SNAP also has an associated stigma and brings the hassles of participating in the program. Heflin and Ziliak found that emotional distress associated with food insufficiency was higher among those who are SNAP recipients. There was some evidence for a dosage effect—food-insufficient individuals who received high amounts of food stamp benefits experienced greater emotional distress than food-insufficient individuals who received lower levels of benefits—and the effect was highest during the transition onto SNAP.

Research Considerations

Heflin pointed to two important research topics:

-

Mismatched Time Horizons: Food insufficiency is often a very short term problem, said Heflin. Shortages may last only a few days, and they can usually be remedied at low cost. Weight gain, in contrast, is a long-term process. It is the result of cumulative disadvantages, and remedies are costly and difficult to implement. What long-term processes related to obesity do short-term spells of food insufficiency trigger in terms of mental health problems, metabolic processes, or access to food supplies?

-

Subgroup Differences: There is some evidence that African-American women are protected from the negative effects of obesity and food insufficiency, at least in the labor market. It is unclear if this is also true for other groups. Understanding these subgroup differences and focusing on protective factors may be critical in planning effective interventions.

A LIFE COURSE PERSPECTIVE

As discussed earlier in the workshop, many studies have found that children growing up in poverty and in families of low socioeconomic status (SES) have a slew of negative outcomes overall, said Maria Melchior of the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research. Low socioeconomic position predicts higher rates of death in infancy and childhood, low birth weight, disability—even after accounting for birth characteristics and birth weight, acute illnesses, the recurrence and severity of chronic illnesses, and poor health behaviors such as poor diets (Spencer, 2008). Furthermore, these associations are not limited to the most disadvantaged but are distributed in a gradient across the whole population.

Research also shows that children growing up in disadvantaged conditions have poorer cognitive and behavioral outcomes on average than other children (Berger et al., 2009). As early as age 3, children who grow up in low-SES families tend to have lower language ability and cognitive scores and more behavioral problems.

Evidence regarding the association between childhood health problems and later socioeconomic attainment comes from the British birth cohort studies that followed samples of the general population born in 1946, 1958, and 1970 (Case and Paxson, 2006). Data from these studies suggest that there is a strong link between very early childhood health characteristics such as birth weight and later occupational and socioeconomic attainment in adulthood. Part of this association appears to be mediated by educational attainment because children with health problems tend to have worse academic achievement. Children with physical and behavioral difficulties have more problems concentrating in the classroom and also miss more school days on average, which contributes to their educational outcomes. Poor nutrition may also play a role for children, as in the case of iron deficiency anemia.

The association between childhood health and later academic and socioeconomic attainments is especially strong in children who come from low-SES families. Also children who have poor health are more likely to have health problems in adulthood, which can affect their success in the labor market.

Childhood SES and Health

Melchior has studied the association between childhood socioeconomic position and adult health in collaboration with a group headed by Terrie Moffitt and Avshalom Caspi, who are both at Duke University. They have used data from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, which is a birth cohort of 1,000 individuals born in New Zealand in 1972 and 1973 who have been followed regularly until, most recently, age 32. This long-term follow-up has made it possible to study the association between early life characteristics and later health in detail.

In a study of multiple health outcomes at age 32, Melchior et al. (2007) found no association between childhood SES and adult depression or anxiety disorders. However, they found that children growing up in low-SES families were 2.27 times more likely at age 32 to have tobacco dependence, 2.11 times more likely to have alcohol or drug dependence, and 2.50 times more likely to have cardiovascular risk factors, including obesity, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and low cardiorespiratory fitness.

The longitudinal follow-up of the Dunedin cohort allowed the authors to test some of the mechanisms that might explain these associations. They found that the association between low childhood SES and cardiovascular risk factors decreased when they controlled for parental heart disease, childhood body mass index (BMI), childhood IQ, childhood maltreatment, and adult SES. In the full model, approximately 64 percent of the observed association was explained by these factors. These data suggest that the association between childhood socioeconomic position and adult cardiovascular health is multifactorial, Melchior said.

Food insecurity can be one aspect of low socioeconomic position. Using data from a cohort of 2,000 twins born in Britain in the early 1990s, the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) cohort study, Melchior and her colleagues found that food insecurity in childhood was associated with lower IQ, more behavioral problems, and more emotional problems among children (Belsky et al., 2010). These associations remained even after accounting for such factors as household income, health and personality, parenting characteristics, and childhood maltreatment.

Mental Health

One possibility, said Melchior, is that food insecurity in low-SES families may be related to the parents’ psychological difficulties. Data from the E-Risk cohort suggest that the strongest factor predicting exposure to food insecurity among low-SES families was the presence of maternal mental health problems (Melchior et al., 2009). Among low-SES

families that did not experience food insecurity, approximately 40 percent of mothers had mental health problems such as depression, substance dependence, psychotic features, or exposure to domestic violence, compared with 60 percent among families that experienced transient food insecurities and 68 percent among families that experienced persistent food insecurity. In families that experienced persistent food insecurity, 30 percent of mothers had three or four mental health problems. The single factor that discriminated between low-SES families that did or did not experience food insecurity was maternal mental health problems. “Unfortunately, we did not have data on fathers’ mental health, and to my knowledge there [are few] data on this, but it will be very interesting to include paternal characteristics in the study of determinants of food insecurities in the future.”

Is food insecurity a cause of poor health? The association could be spurious if it is a reflection of a common cause, such as parental mental health problems. However the association is strong even when accounting for a number of covariates, including family socioeconomic characteristics, parenting characteristics, and exposure to other forms of difficulties such as neglect and mistreatment. This strengthens the claim that the association is causal, though causation remains difficult to demonstrate.

Effects Over the Life Course

In understanding the long-term links between socioeconomic position, food insecurity, and health, a life course framework is helpful, said Melchior. This framework searches for the biological, social, behavioral, and psychosocial risk factors for poor health over time. Three conceptual models have been suggested.

First, there may be critical or sensitive periods during which exposure to particular risk factors has long-term consequences for health and behavior. For example, Olson et al. (2007) found that food insecurity early in childhood had an important impact on the later relationship of women to food.

Exposure to cumulative disadvantage also could be critical. Some evidence suggests that individuals who experience worse socioeconomic circumstances throughout life have the highest risk of cardiovascular disease and also obesity (Galobardes et al., 2006).

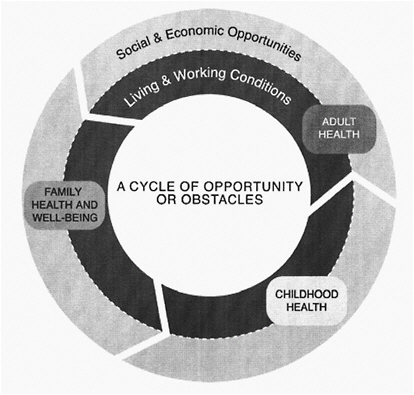

Finally, the best way to think about the association may be through a chain of risks in which there are probabilistic associations between low family income, low education, and low adult SES (Figure 5-1).

Research Needs

Melchior listed a number of research needs:

-

Longitudinal studies—in particular, birth cohort studies or cohort studies that start early in childhood—are especially informative.

-

Information on life course circumstances collected in cross- sectional studies also can be quite informative on how health and socioeconomic position unfold over a person’s life.

-

Long-term evaluations of policies in this area are important, because current findings suggest that favorable living conditions in childhood can improve health and socioeconomic outcomes concomitantly and later in life.

-

The many risk factors and mechanisms that can explain the association between poor SES and poor health need to be examined.

FIGURE 5-1 Health is shaped by social advantages and disadvantages across lifetimes and generations.

SOURCE: Braveman and Egerter, 2008.

-

Because most health outcomes are distributed along socioeconomic gradients in the population, it may be possible to learn about the role of food insecurity in health by looking at large population samples and not just at the most disadvantaged populations.

-

Mental health problems need to be a focus of research, given their strong association with food insecurity.

-

To improve children’s health and future prospects, the attitudes, parenting skills, and other characteristics of the adults with whom children live need to be studied, because these can have a strong influence on health in the next generation.

POVERTY AND FOOD INSECURITY

Another way to study the relationship between food insecurity and obesity is to look at changes in SES, food security, and obesity, observed Sandra Hofferth, professor in the Department of Family Science at the University of Maryland. She began by highlighting national prevalence data based on the nationally representative Panel Study of Income Dynamics. In 1997, 87 percent of families with children were food secure. In 1999, 85 percent were food secure—so over this period, the percentage of families with children that were food insecure rose from 13 to 15 percent. Fewer than 4 percent of families experience hunger, and children are usually protected. When children had to go hungry, “we had a lot of people who were in tears,” said Hofferth. “That is a very stressful situation.”

To study dynamics of food insecurity, Hofferth looked at a subset from the Panel Study of 2,258 families with children under age 13 in 1997 and again in 1999. She calculated “persistence” as the number that were food insecure in both years divided by the number that were insecure in 1997. She calculated “entry” as the number that became food insecure between 1997 and 1999 divided by the number that were secure in 1997.

About 90 percent were food secure in 1997, and of those about 7 percent were insecure by 1999. Families were more likely to become food insecure if they had low income in both years.

About 10 percent were food insecure in 1997, and of these about half were still insecure in 1999. If they became poor between 1997 and 1999, they were more likely to remain food insecure than those that were never poor.

Thus, there is a small amount of movement into food insecurity and a large amount of movement out. Changed economic conditions are the key to either exit or persist once you are food insecure, Hofferth said.

Low income is one of the main correlates of food insecurity in families. Families that are persistently poor are likely to become food insecure;

if they are food insecure and become poor they are more likely to remain food insecure. According to Rank and Hirschl (2009), about half of U.S. children are in a family that has ever received SNAP, but only one-fifth are in a family that has received SNAP for 5 or more years.

Low Income and Diet

Regarding the link between low income and childhood obesity, a possible causal mechanism is that low-income children eat a higher proportion of low-quality, high-fat food than children from higher-income families. Another possibility is that inadequate food may lead to binge eating when food is available. Using the Child Development Supplement to the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, Hofferth and Curtin (2005) looked at detailed information on food expenditures, food assistance programs, food insecurity, and overweight and obesity measured directly in children. They constructed a model in which food consumed is a function of spending on food at home, spending on food outside the home, food stamp supplements, participation in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), family income, employment status, education, and other factors.

Children whose families are poor have the lowest expenditures on food—about $5,000 in 1997. Food expenditures jump dramatically for families at 100 to 130 percent of the poverty line, to about $6,000 annually, and they rise as income goes up.

Children who were poor had lower rates of obesity than children who were near poor, working class, or of moderate income, explained Hofferth. Children in high-income families had lower rates of obesity, but not as low as the poorest children. These data are relatively old and should be updated, said Hofferth, but they show that there is no simple linear relationship between income and child overweight. Low-income families do not have as much money to buy food. Children just above the poverty line have higher rates of overweight, possibly because they spend more money for lower-quality food. Higher-income families buy higher-quality food. “We need to understand more about the quality of lower- and higher-income family expenditures on food,” she said.

Another important point is that it can be misleading to extrapolate from parents to children. Children often appear to be protected from food insecurity, although very poor low-income children clearly need assistance from food programs, Hofferth said.

It also is important to examine total expenditures on food, including the School Breakfast Program, the NSLP, and food stamps. Children get food from multiple sources, not just one.

Hofferth recommended that the dynamics of poverty and food insecurity be incorporated into research. Many families are poor at one time

but not over longer periods, which can be critical to their food security, she said.

Are there other critical periods besides the fetal period? Are there factors that are more or less important at different points in a child’s life? These are important issues to examine, said Hofferth.

GROUP DISCUSSION

Moderator: Christine Olson

During the group discussion period, points raised by participants included the following:

African-American Women

Angela Odoms-Young offered a different interpretation of the observation that African-American women are protected from the negative consequences of obesity in the labor market. Perhaps the racial discrimination they face is so significant that weight-related discrimination does not produce an added effect. Heflin agreed that such an interpretation could be correct. She also observed that there may be an acceptance of body shape in African-American cultures that is protective. Research on the lack of an added effect would be interesting in documenting the degree of discrimination that African-American women experience. Wendy Johnson-Askew said that African-American women may be resilient in the face of historical trauma, especially given that they have had to enter the workforce in large numbers. In that case, “resilient” may be a better way of describing the effect than “protective.”

Food Insecurity and Mental Health

In response to a question about the influence of food insecurity on mental health, Melchior said, “There is no question that experiencing life events and difficulties such as food insecurity can further hamper individual’s mental health, especially if women are depressed.” Her research has found an association not only with depression but also with alcohol and drug abuse and schizophrenia. These conditions are probably not caused by food insecurity, but they can be exacerbated by concern over food and other disadvantages. In response to the same question, Heflin said that her research produced evidence for causal influences extending in both directions. Food insufficiency is a risk factor for emotional distress and depression, and a change in mental health status is associated with a move into food insufficiency. Hofferth added that there is great interest

in precursors to mental health problems that may be triggered by adverse circumstances.

Mark Nord pointed to a possibly false measurement correlation between depression and food insecurity. “A person who is depressed probably sees a lot of things as worse than they might on a day when they weren’t depressed.” Because food insecurity is self-reported, someone who is depressed may be more likely to report subjective food insecurity than someone who is not depressed, whereas the two individuals may actually be experiencing the same level of objective food insecurity—this would lead to a measurement bias. A possible way to overcome this problem would be to use longitudinal studies to look at correlations between food security and measured outcomes as opposed to reported outcomes. Melchior agreed that the validity of an individual’s self-report when that person is unwell is important and pointed to two other ways to deal with this issue. One is to use multiple informants who can gauge an individual’s mental health. The second is to take personality characteristics such as negative affectivity into account.

Olson discussed an upcoming paper that looks at families in which one person is removed from the workforce, income plummets, and the family becomes food insecure. If the jobless person becomes depressed, the partner sometimes has to decrease work hours to care for that person, exacerbating the loss of income and creating another way in which food insecurity might be related to depression.

Measuring Stress and Depression

Edward Frongillo observed that the literature on stress often uses the same items to measure depressive symptoms and to conceptualize depression as a mental health entity. “That leaves us in a bind as to how to separate those things, because in a certain sense they can’t mean the same thing.” Melchior agreed that there are no biological tests for depression but returned to the idea of having multiple informants to strengthen a diagnosis rather than relying solely on a person’s self-report.

REFERENCES

Belsky, D. W., T. E. Moffitt, L. Arseneault, M. Melchior, and A. Caspi. 2010. Context and sequelae of food insecurity in children’s development. American Journal of Epidemiology 172(7):809-818.

Berger, L. M., C. Paxson, and J. Waldfogel. 2009. Income and child development. Children and Youth Services Review 31(9):978-989.

Braveman, P., and S. Egerter. 2008. Overcoming obstacles to health: Report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Commission to Build a Healthier America. Washington, DC: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America.

Case, A., and C. Paxson. 2006. Children’s health and social mobility. Future of Children 16(2):151-173.

Cawley, J., and S. Danziger. 2005. Morbid obesity and the transition from welfare to work. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 24(4):727-743.

Corcoran, M. E., C. M. Heflin, and K. Siefert. 1999. Food insufficiency and material hardship in post-TANF welfare families. Ohio State Law Review 60:1395-1422.

Gallup Organization. 2003. Poll analyses: Smoking edges out obesity as employment liability. August 7.

Galobardes, B., G. D. Smith, and J. W. Lynch. 2006. Systematic review of the influence of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Annals of Epidemiology 16(2):91-104.

Heflin, C. M., and J. P. Ziliak. 2008. Food insufficiency, food stamp participation, and mental health. Social Science Quarterly 89(3):706-727.

Heflin, C. M., K. Siefert, and D. R. Williams. 2005. Food insufficiency and women’s mental health: Findings from a 3-year panel of welfare recipients. Social Science and Medicine 61(9):1971-1982.

Heflin, C. M., M. E. Corcoran, and K. A. Siefert. 2007. Work trajectories, income changes, and food insufficiency in a Michigan welfare population. Social Service Review 81(1):3-25.

Hofferth, S. L., and S. Curtin. 2005. Poverty, food programs, and childhood obesity. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 24(4):703-726.

Lindeboom, M., P. Lundborg, and B. Van Der Klaauw. 2010. Assessing the impact of obesity on labor market outcomes. Economics and Human Biology 8(3):309-319.

Melchior, M., T. E. Moffitt, B. J. Milne, R. Poulton, and A. Caspi. 2007. Why do children from socioeconomically disadvantaged families suffer from poor health when they reach adulthood? A life-course study. American Journal of Epidemiology 166(8):966-974.

Melchior, M., A. Caspi, L. M. Howard, A. P. Ambler, H. Bolton, N. Mountain, and T. E. Moffitt. 2009. Mental health context of food insecurity: A representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics 124(4).

Olson, C. M., C. F. Bove, and E. O. Miller. 2007. Growing up poor: Long-term implications for eating patterns and body weight. Appetite 49(1):198-207.

Puhl, R., and K. D. Brownell. 2001. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obesity Research 9(12):788-805.

Rank, M. R., and T. A. Hirschl. 2009. Estimating the risk of food stamp use and impoverishment during childhood. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 163(11):994-999.

Roehling, M. V. 1999. Weight-based discrimination in employment: Psychological and legal aspects. Personnel Psychology 52(4):969-1014.

Spencer, N. 2008. Health consequences of poverty for children. London: End Child Poverty.

Tunceli, K., K. Li, and L. Keoki Williams. 2006. Long-term effects of obesity on employment and work limitations among U.S. adults, 1986 to 1999. Obesity 14(9):1637-1646.