6

Socioecological Perspectives: The Family and Household Level

|

Key Messages Noted by Participants

|

In the socioecological model, the next level beyond the individual is the family or household, two terms that are often but not always synonymous. Families can have both protective and deleterious effects on food insecurity and obesity—sometimes at almost the same time. The complex dynamics within families provide a rich area for research, said Amy Yaroch, executive director of the Center for Human Nutrition in Nebraska, who moderated the session on family and household perspectives at the workshop.

FOOD INSECURITY AND CHILDREN

Food insecurity is linked not only to maternal stress and depression but also to the psychosocial functioning of children, said Edward Frongillo, Jr., professor and chair of the Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior at the Arnold School of Public Health at the University of South Carolina at Columbia. One important reason why these may be linked is through family processes, but much less is known than is needed about parent-child interactions, family eating patterns, and the social context of family life.

Much of what is known comes from the perspectives of mothers, which is reasonable because they are often the primary decision makers about food. Frongillo explained that his research has sought to extend knowledge about how family members experience and manage food insecurity. In particular, he has sought to understand children’s experiences: why and when does food insecurity happen, what do children feel about it, what happens to them as a result of food insecurity, how are they facing it, and are they protected against it?

He discussed three studies: two in-depth qualitative studies that were done in South Carolina and one mixed-method study (Bernal et al., 2009) done in the state of Miranda in Venezuela. For the presentation, Frongillo combined the data from the South Carolina studies, yielding 38 families, split between urban and rural regions, that were interviewed. The sample included African Americans, whites, and Hispanics with children ages 9 to 17. Of these families, 17 had very low food security, 12 had low food security, and 9 were food secure. These families received the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, and nearly all of them were receiving free or reduced-price school lunches and/or breakfasts.

In the study in Venezuela, interviews with children using both focus groups and individual interviews were followed by cognitive testing, a field survey, and a survey of children-mother dyads, with an overall sample of 131.

Frongillo said that the results from the studies in South Carolina and Venezuela demonstrate that food insecurity affects children in terms of both awareness and responsibility. Awareness has cognitive, emotional, and physical dimensions. Responsibility involves participation, children’s own initiatives, and the resources children generate themselves. He went through each of these elements in turn.

Children and Awareness

Frongillo said that cognitive awareness implies knowing about food scarcity and the family challenges that are created by it. Children are aware

of the inadequate quantity or quality of food, the struggles that adults are going through to meet food needs, and the limitations of resources for meeting those needs. Parents can share this information with children, or children can draw conclusions based on their own observations.

Emotional awareness constitutes feelings such as worry, sadness, and anger that are related to knowing about food scarcity and the challenges it creates, Frongillo continued. It includes being aware of worries about food and also worries about what parents and others who are supposed to be providing for the family are going through. Contributors to these worries are lack of confidence that adults will in fact work it out and the child’s vigilance. As one African-American, female high school student said, “They don’t really say anything, but you can read it in their face or if they’re out of money, you just know. I just know. It’s not really what they say, it’s just how they act when they’re out of money and you ask why you don’t go to the store and they don’t answer or something or they just try to find other ways, like they just forget. I can tell by people’s expression. My older sister wouldn’t be frowning, but like it wouldn’t be a happy face. It wouldn’t be a sad face. It wouldn’t be any face at all. It would be just like an empty face.”

Physical awareness consists of feelings such as hunger, pain, tiredness, and weakness that are related to food insecurity. Some contributors to these feelings are not having food at home or having poor-quality food, the poor quality of food served in schools, and also limitations in what parents are able to do.

Frongillo read a quote from an African-American, male high school student who was asked how he felt when he was hungry. The youth said, “Angry, mad, go to sleep basically. That’s the only thing you can probably do and after you wake up, you feel like you’ve got a bunch of cramps in your stomach and you’ll be light headed.”

Children and Responsibility

Children are not only aware of what is going on, they take responsibility, said Frongillo. They go along with adult strategies for managing food resources. They eat less when asked, choose less-expensive foods or only foods that are judged to be healthful, or accompany parents and help them at the food pantry. Children also initiate strategies to stretch existing food resources by eating less without being asked, by encouraging others such as their siblings to eat less, and by asking for less food or less-expensive foods.

Children also take action to attain additional food or money for buying food such as having a part-time job, taking on informal work, giving money to the household, asking neighbors for food, or eating away from home so

that they will not draw on the food supply at home. They might also bring food home after a stay at a father’s house if the parents are separated.

Frongillo relayed a quote from one child who said: “We’ll get together and we’ll find a way to get money up, not—we ain’t got to sell no drugs, not like that, but we’ll find a way to get money up. We might all get together and cut the grass or something. Sometimes they’ll probably, like, people will be putting up money on fights and stuff and they might do dog fights every now and then to get money.”

The study done in Venezuela produced quantitative information about this behavior. It indicated that children with food insecurity live adult roles, Frongillo concluded. They do more activities related to household chores such as ironing, washing, cooking, and taking care of siblings. They do more paid work. They engage in fewer activities related to school recreation and resting. They sacrifice time for activities that would increase their learning and quality of life.

Protection of Family Members

Based on the interviews conducted by Frongillo and his colleagues, parents try to provide for the quality and quantity of food. They also provide emotional support around eating.

Protection extends in multiple directions. Parents try to protect children and other parents. Children try to protect parents, especially mothers, and other children, especially younger children and poorer children.

However, Frongillo said, sometimes parents do not protect children, especially when there are mental health problems, unemployment, drug or alcohol problems, or deep poverty.

Consequences of Food Insecurity

These reactions to food insecurity produce compromised opportunities for children to study, play, rest, and live a happy childhood, Frongillo said. Furthermore, parents may be very much unaware of at least some of their children’s experiences of food insecurity. This has two importance implications.

One is that researchers likely underestimate the prevalence of experiences of food insecurity among children given the measurement tools currently available. The second, Frongillo continued, is that the idea that children are protected from food insecurity by the parents is a myth. “It is a myth in the epidemiological sense of shared belief, and there is a need for the scientific community—frankly, this community—to stop perpetuating that myth.”

Myths are tied to roles, said Frongillo. There is a shared belief that mothers’ roles are to manage the household, manage the family, manage

resources, and protect the children. Their understanding of their experiences is shaped by the shared beliefs of the broader society.

Fathers also have a role. They talk about being the provider and protecting their wife and children. Frongillo stated that children also are active contributors. They are very aware that parents believe their role is to protect them. Children purposely do not tell their parents about some of the things that are going on because they want their parents to continue to believe that they are protecting their children.

“We have seen this play out even within one family,” said Frongillo. “The father will be talking about how he is making sure his wife doesn’t have to worry about having adequate food available and the things that he is doing to do that and protect her and the children. The wife is talking about how she tries to manage things so the father does not have to worry about all of these issues and to protect the children. Then, the children are telling us basically they know what is going on.”

Balancing Capabilities and Demands

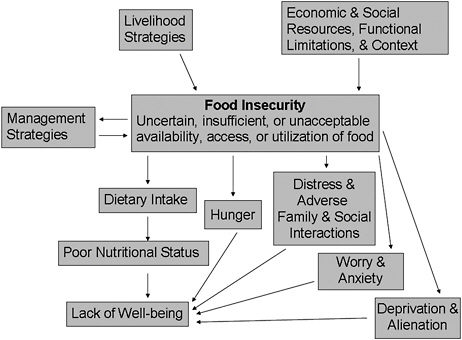

Frongillo showed a diagram from a National Research Council (NRC, 2006) report that he believes summarizes the balancing that occurs within families (Figure 6-1). The top of the diagram represents the balancing that occurs around food insecurity, making a livelihood, and other inputs. The bottom of the diagram represents the multiple pathways through which food insecurity affects well-being. The idea that children are not being affected because the pathways to them are being blocked by parents is not accurate, Frongillo maintained. “We know there are lots of effects on children that must be operating through those pathways.”

Frongillo said that families balance capabilities and assets against demands and stressors. They also balance among the goals that they have for their children, including goals for security, certainty, safety, good nutrition and health, education, emotional and social development, family cohesion, belonging, acceptance, and feeling normal. Especially if parents are poor, they often have to make choices among these goals. Parents and children may say that they should not be eating fast food all the time, but that may be the only way for a parent to communicate to a child that a family is not deprived.

This balancing occurs within an environmental context, Frongillo explained. Beliefs about the roles in society, including parenting, are shaped by very powerful forces in society. The fast-food industry spends a huge amount of money to convince families that it is normative to go to fast-food restaurants. “I am not picking on them,” Frongillo explained, “it is just exemplary. But what is happening is that these forces in society are shaping the way in which we think, the way we believe that we should be going about working together in our families.”

FIGURE 6-1 Families must balance many factors in efforts to remain food secure.

SOURCE: NRC, 2006.

In late 2010, Sesame Workshop was scheduled to release a program developed to help food-insecure families cope in a way that does not promote obesity, Frongillo reported. “But this is like a drop in the bucket compared to the influences that are there in our larger society.”

Frongillo ended by stating that food-insecure families have limited choices to achieve belonging, acceptance, and normality. They are susceptible to the food environment and to the larger environment. Balancing has to be done in a way that is integrated with influences from that environment. The environment has a larger impact on lower-income families because they cannot make the same choices more affluent families can.

These observations lead to four high-priority questions, said Frongillo:

-

How do roles and myths of family members play out in responding to food insecurity?

-

How do families balance among demands and goals for children under resource constraints?

-

How does the balancing of resource-constrained families interact with the food environment, and how do these processes put children and adults at risk of obesity?

-

What aspects of children’s experience of food insecurity are most important, and how should these experiences be assessed?

CYCLES OF POVERTY AND FOOD INSECURITY

For the past 7 years, Mariana Chilton, associate professor in the Department of Health Management and Policy at the Drexel University School of Public Health, has been using qualitative methods to study vulnerabilities within households in Philadelphia.

Household Context Influences Well-Being

Household context affects dietary intake, nutritional status, hunger, distress, adverse family and social interactions, worry, anxiety, and well- being. Household context also contributes to six categories of vulnerability:

-

Economic insecurity

-

Overeating and deprivation

-

Stress and depression

-

Exposure to violence

-

Lack of care for self

-

Talk about the food environment

Examination of these vulnerabilities in turn makes it possible to talk about ways of protecting families from them. “I want us to broaden our thinking to talk not just about food assistance but about housing subsidies, energy assistance, and other types of income support programs that all can help contribute to well-being, to economic security, and to providing more opportunities to families,” said Chilton.

Partnering with Families to Create Solutions

Researchers need not to target families but to partner with families “because they are the ones who actually have the answers,” said Chilton. Families are not just passive recipients of aid and advice. They are purposeful agents that want to break the cycle of poverty and despair. They have a variety of needs, including good nutrition, good housing, good energy assistance, utilities, good health, job training and job opportunities, access to financial services, and access to information. One way to meet these needs is to focus on parents’ attitudes toward their children. Another is to recognize the economic creativity that these parents bring to their lives.

The studies Chilton described treated the family as a dynamic unit. Families extend beyond the traditional parent-child dyad to include grand-

parents, aunts and uncles, nieces, nephews, and other children who may be coming in for the weekend or during the week. Also, many families in Philadelphia temporarily adopt unrelated young people to help them cope with economic insecurity and with safety issues. The local teenager or an elderly woman in the neighborhood may also constitute family or the household. Families also may hide the fact that some family members are part of a household to retain public assistance.

Research Findings

As examples of this research, Chilton described three qualitative studies done in Philadelphia. The first was the Women’s Health, Hunger, and Human Rights study, in which she and her colleagues interviewed 34 women who used food cupboards or food pantries in Philadelphia and conducted four focus groups (Chilton et al., 2002; Chilton and Booth, 2007). As they were doing the interviews, they tested their hypotheses against what the women were saying in “a reciprocal process of [hypothesis] generation.”

The second study she discussed is Children’s HealthWatch (Chilton et al., 2011), a multisite study of 50 caregivers with children that looked at the impact of public policies on the health and well-being of young children. The interviews are finished and are being analyzed to make possible a multimethods analysis.

The third study was Witnesses to Hunger, a participatory research project begun in 2008 that is ongoing (Chilton et al., 2009a, 2009b, 2010). It has morphed into an ongoing ethnographic study in which 42 women with at least one child under the age of 3 use cameras and a photovoice methodology to take pictures of their experiences of what it is like to raise their children in poverty and to talk about their ideas for change. “The participant then becomes the person who is supposed to be framing the issue for the researcher.” The researchers conducted one-on-one semistructured interviews with the women to ask why they took that picture, what they wanted people to see, and what they wanted people to do. The women also came together in focus groups to share their photographs and talk about their priorities.

Breaking Cycles of Violence

Chilton devoted most of her presentation to an analysis of the photographs taken through the Witnesses to Hunger project. These photographs, of which more than 10,000 have been taken, are both data and testimony. Chilton showed several at the workshop as a reminder of the stark conditions in which many families live. She also provided brief summaries of the difficult lives of the people who took the photographs. Most of the women

in the Witnesses to Hunger program have experienced rape, abuse, and neglect. Many have seen family members and friends murdered. Children who grow up under such conditions can contribute to a cycle of violence. “What happens is that the women and kids stop caring for themselves and start getting very angry, which then continues to perpetuate the situation.”

The women in these studies want to break the cycle of violence. They “want the next generation to be better and better and better,” said Chilton. “This is something we can really capitalize on.” Many of these women have side businesses in which they use their creativity to survive. For example, a woman might braid hair to bring in money off the books. “They are entrepreneurs. They know what they are doing and they are super creative. There is no way that they would be actually able to survive and feed their families if they weren’t having these little side businesses.”

These people experience hunger and poverty firsthand, which makes them invaluable partners for researchers. Based on her experiences, Chilton made several recommendations:

-

Seek to partner with study participants.

-

Conduct intervention research aimed at improving economic well-being.

-

Conduct intervention research aimed at improving the food environment.

-

Conduct intervention research aimed at linking the prevention of violence with the prevention of food insecurity.

NUTRITIONAL CHALLENGES IN TEXAS COLONIAS

Joseph Sharkey, professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Health and director of the Program for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities, School of Rural Public Health at the Texas A&M Health Sciences Center, discussed the work he has done with Mexicano families in Texas colonias. Colonias run across the entire border of Texas from El Paso to Brownsville. These are rapidly growing areas with high and persistent poverty. There are more than 1,500 colonias along the Texas border, more than 70 percent of which are in Hidalgo County.

Many colonias lack basic services, have inadequate roads and drainage, and provide limited access to safe water and sewage. Housing includes single-pull trailers, double-lot trailers, and recycled materials. They tend to be low-density settlements, and many are outside cities, which means they are the responsibility of individual counties that may or may not provide needed services.

Residents in these areas have high rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes among children, food insecurity, and neighborhood deprivation. They also tend to be located at a great distance from supermarkets and health care, and they generally have no public transportation.

Influences of Food Choices

Sharkey and his colleagues have focused on the food choices that resource-limited families make. They use community surveys, participant observations, household food inventories, longitudinal studies of mother-child dyads, focus groups, and participant-driven photo elicitation. Indigenous health workers, or promotoras, who participate in the research “are our eyes and ears in the community,” and serve as cultural brokers with community residents, explained Sharkey.

In a door-to-door survey of 610 households, overweight and obesity were determined through self-reported height and weight (Sharkey et al., 2010a, 2011). These households made heavy use of SNAP, WIC (the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children), and the School Breakfast Program and National School Lunch Program. They had very high rates of very low food security as reported by the mothers and children. In addition to this survey, the promotoras spent extended periods in the home to get a sense of food choice, and photo elicitations produced additional information (Johnson, 2010; Sharkey et al., 2010b).

Overall, the results of this work show that this is a highly resilient population in the face of very few resources, according to Sharkey. They have very limited opportunities for physical activity, largely as a result of free-roaming dogs and other neighborhood structural limitations. Also, the houses are small, so there is not much room to play. One household put toys in a van parked outside in which the child would play.

Influences on Food Intake

The mothers consider themselves reinas de la cocina—queens of the kitchen, but insufficient financial resources exert great pressure on consumption by both children and friends of children. One mother had a 16-year-old son whom she wanted to keep out of gangs. He comes home immediately after school and stays there, but he wants his friends to come over, too. “She said yes. But what do 16-year-old boys do? They eat a lot. What is she struggling with? She is struggling with this competing demand of making sure there is enough food there for her family to eat but at the same time keep her son free from the gangs.” Other factors that influence food availability in the home and subsequently food choice include wage earners’ poor health, limited storage and cooking facilities, inadequate or costly transportation, and competing demands for resources.

Mothers seek to go beyond basic nourishment to communicate their love, their values, their expert use of resources, and their ability to provide delicious and available food. Many rely heavily on tortillas, because they are cheap to make, they are filling extenders, and they have multiple roles in

meals. Mothers get up early to prepare tamales and lunch so that children do not have hunger as an excuse for not learning. Households tend to lack fresh or processed fruits. The most frequent items found in households are whole milk, sugar-sweetened beverages, sugar cereal, corn tortillas, and lard, which must have an effect on dietary intake and obesity, according to Sharkey.

Sharkey listed a number of high-priority research gaps:

-

Understanding the context in which people live,

-

Establishing a frame of reference for measurements,

-

Investigating the frequency and duration of food insecurity,

-

Analyzing the role of physical activity,

-

Thinking about how food security might differ between the family and the individual, and

-

Facilitating improvements in food security.

GROUP DISCUSSION

Moderator: Amy Yaroch

During the group discussion period, points raised by participants included the following:

Measures of Food Insecurity

In response to a question from Amy Yaroch about whether 24-hour recalls of foods eaten pick up such things as sugar added to coffee, Sharkey expressed the opinion that such measures probably severely underestimate the extent of food insecurity, because the families in his survey believe that they can make a meal out of anything, even just a little hominy. He and his colleagues are currently analyzing the first wave of dietary intake data to answer this and other questions.

Incorporating Qualitative Methods into Quantitative Research

Craig Gundersen pointed to the emotional impact of qualitative research and asked how investigators who do quantitative research can incorporate the insights of qualitative research into their work. Chilton responded by recommending that quantitative researchers partner with an anthropologist, sociologist, and/or other social scientist. Together, these teams can develop protocols in which questions in national datasets are tested locally to provide a sense of context. Partnerships with communities also can help reveal the best questions to ask and the best ways to translate research findings into actions that are meaningful for the community. This

is extra work, Chilton said, “but there need to be more types of community forums in which researchers are able to talk to regular people who know those experiences firsthand.”

Gundersen also asked how to incorporate the views of children into research along with those of adults. Frongillo pointed to three studies that have done surveys simultaneously of children and adults: one in Zimbabwe, one in Ethiopia, and the study he described in Venezuela. Such studies can derive survey questions for both children and adults from qualitative work, but the questions and responses still need to be validated with both adults and children. The three surveys he cited have had “astonishingly low” concordance between the responses of adults and children. “We need to understand whether that reflects measurement problems, or whether that is indicating that they really are experiencing and therefore reporting on very different experiences within the household.”

Beyond Weight

Nicolas Stettler pointed out that it takes a lot of work to treat obesity. When families are wracked by violence, neglect, and poverty, they have greater problems than weight. Gundersen agreed that it is much more important for families not to be poor than not to be overweight, which re-emphasizes the importance of addressing issues of food insecurity independently from issues of obesity. Chilton pointed out that the primary concern of people who are food insecure and living in poverty is how to get through the day. Yet it is also the case that a profound effect of the Witnesses to Hunger program has been that some of the women who are overweight have gone on diets, have started to eat better, and are watching their weight. However to help them focus on weight as a priority, they need help with housing, energy, transportation, jobs, and economic opportunity.

Research Priorities

One workshop participant pointed out that priorities for researchers should not be seen as either-or propositions. Research on obesity can be linked to research on food insecurity, and obesity can have a very negative impact on adults and children. Factors such as stress, advertising, and the cyclicity of food insecurity all establish links between poverty and obesity, and these problems could be tackled simultaneously.

Frongillo replied that food insecurity is a valuable marker of families that are struggling and at risk for many problems, including obesity. Thus, conducting research on obesity is a way to bring attention and resources to families that need to move from where they are.

REFERENCES

Bernal, J., H. Herrera, S. Vargas, E. A. Frongillo, and J. Rivera. 2009. Food insecurity from the perspective of children and adolescents in Venezuelan communities. Presented at the Society for Latin American Nutrition, XV Latin American Congress of Nutrition, November, 2009, Santiago, Chile.

Chilton, M., and S. Booth. 2007. Hunger of the body and hunger of the mind: African American women’s perceptions of food insecurity, health and violence. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 39(3):116-125.

Chilton, M. M., E. Ford, M. O’Brien, and L. Matthews. 2002. Hunger and human rights in Philadelphia: Community perspectives. Presented at the American Public Health Association, Annual Meeting, November 9-13, Philadelphia, PA.

Chilton, M., J. Rabinowich, C. Council, and J. Breaux. 2009a. Witnesses to hunger: Participation through photovoice to ensure the right to food. Health and Human Rights 11(1):73-86.

Chilton, M. M., J. Kolker, and J. Rabinowich. 2009b. Witnesses to Hunger: Mothers taking action to improve health policy. Presented at the American Public Health Association, Annual Meeting, November 7-11, Philadelphia, PA.

Chilton, M. M., J. Rabinowich, C. Sears, and A. Sutton. 2010. The violence of hunger: How gender discrimination and trauma relate to food insecurity in the United States. Presented at the American Public Health Association, Annual Meeting, November 6-10, Denver, Co.

Chilton, M., J. Rabinowich, B. Izquierdo, and I. Sullivan. 2011. How the stress of hunger and the stress of advocacy can impact the lives of children. Presented at the Society for Research in Child Development Biennial Meeting, April 1-2, 2011, Montreal, Quebec.

Johnson, C. M. 2010. Using participant-driven photo-elicitation to understand what it takes for a Mexicana mother in the South Texas colonias to feed her family. Presented at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention.

NRC (National Research Council). 2006. Food insecurity and hunger in the United States: An assessment of the measure. Edited by G. S. Wunderlich and J. L. Norwood. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Sharkey, J. R., J. A. St. John, and W. R. Dean. 2010a. Community and household food availability: Insights from a community nutrition assessment conducted in two large areas of colonias along the Texas-Mexico border. Presented at the International Society for Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, June 9-12, Minneapolis, MN.

Sharkey, J. R., A. Garibay, J. A. St. John, W. R. Dean, and C. M. Johnson. 2010b. Observation of food choice from the perspective of mothers in Texas Colonias. Presented at the International Society for Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, June 9-12, 2010, Minneapolis, MN.

Sharkey, J. R., C. M. Johnson, and W. R. Dean. 2011. Association of country of birth with severe food insecurity among Mexican-American older adults in colonies along the South Texas border with Mexico. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics (30)2.