From Impressions to Evidence: A Program for Evaluation

We have described some of what DC has done to implement the Public Education Reform Amendment Act (PERAA) of 2007 and provided a first look at what has happened since the reform law was passed. However, because these first impressions do not support firm conclusions about the effects of the reform initiative or about the overall health and stability of the school system, they should be treated as only the beginning of the process of collecting reliable evidence to guide decisions about the city’s schools. There are no quick answers: education reform itself is a long-term process, and the evaluation of its outcomes also has to be seen in the long term. Thus, our primary recommendation to the city takes the form of a program for ongoing evaluation.

Recommendation 1 We recommend that the District of Columbia establish an evaluation program that includes long-term monitoring and public reporting of key indicators as well as a portfolio of in-depth studies of high-priority issues. The indicator system should provide long-term trend data to track how well programs and structures of the city’s public schools are working, the quality and implementation of key strategies to improve education, the conditions for student learning, and the capacity of the system to attain valued outcomes. The in-depth studies should build on indicator data. Both types of analysis should answer questions about each of the primary aspects of public education for which the District is responsible: personnel (teachers, principals, and others); classroom teaching and learning; vulnerable children and

youth; family and community engagement; and operations, management, and facilities.

The committee believes that a school district should be judged ultimately by the extent to which it provides all of its students—regardless of their backgrounds, family circumstances, or neighborhoods—the knowledge and skills they need to progress successfully through each stage of their schooling and graduate prepared for productive participation in their communities. Our goal is an evaluation program that will document the actions taken by decision makers (city leaders and school officials), the way those actions influence a broad range of behaviors among students, teachers, and school administrators, and the relationships those actions have to a broad range of important outcomes for students. The program should not only provide answers about what has already happened under PERAA, but also support decisions about how to continue to improve public education in DC.

This chapter begins with a description of the committee’s framework for evaluation. We then discuss in detail the way in which ongoing indicators and in-depth studies can be integrated in practice and how the most important priorities for the District of Columbia can be addressed in this framework. The chapter closes with a discussion of the practical challenges of establishing and managing the program we recommend. Our evaluation program addresses the school system of the District of Columbia; as we discuss in Chapter 4, the responsibility for public education is shared among several offices because of the city’s unique political status and structure.

The committee’s framework for evaluation covers both the implementation and effects of PERAA and, more generally, the condition of education in the District. Although the immediate goal for the District is to answer questions about PERAA, we also see an opportunity to build an ongoing program of analyses that will be useful to the District regardless of future changes in governance or policy. Although our proposed framework was developed for the District of Columbia, it can be used in any school district. It is designed to be adaptable to changing priorities and circumstances as well as to the varying availability of resources to support evaluation, in DC and in any school district.

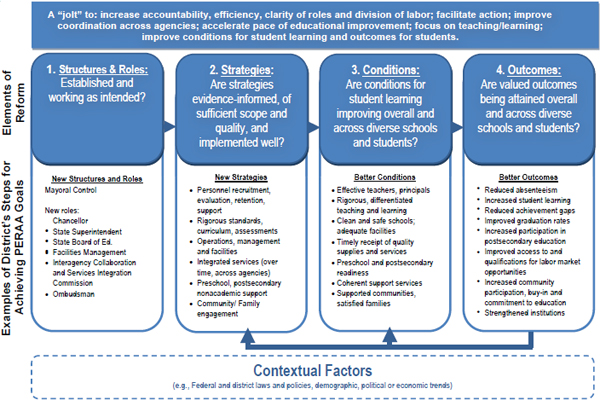

Figure 7-1 depicts our proposed evaluation framework, which begins with the goals the District has set for itself, as shown in the horizontal box that appears at the top of the figure. The logic of this framework reflects a point that may be obvious but is worth underscoring: passing a law does not automatically result in increased student learning, reduced achievement

gaps, increased graduation rates, or other valued outcomes. For these outcomes to occur in DC, the new structures and relationships that PERAA mandated must be established and working as intended; school system leaders must identify and adopt strategies likely to be effective; those strategies must be understood and well implemented; and the conditions for student learning—for example the quality of school staff and instruction—must improve. These prerequisites—or phases of reform—are represented in the first three vertical boxes in Figure 7-1. The fourth box represents a sample of ultimate outcomes for the system (e.g., strengthened institutions) and for students (including academic ones, such as increased learning and participation in postsecondary education, and nonacademic ones, such as reduced absenteeism).

The purpose of the framework design is to ensure that the evaluation encompasses all of the primary elements that could contribute to the outcomes. The framework simplifies the realities of urban school districts in order to help evaluators and the entire community make sense of a complex reality and to ensure that a full range of data are collected to answer the most important questions. As noted above, it is designed to accommodate the city’s changing priorities and concerns over time.

The evaluation is envisioned neither as a one-time study nor as just the annual collection of certain data, but, rather, as a continuing process of data collection and analysis. As the District’s public school system responds to new information and makes changes, the evaluation agenda should also evolve. The arrows beneath the model represent the potential responsiveness of strategies and conditions to changes in outcomes.

The framework also reflects the fact that contextual factors, such as changing demographic, political, cultural, and financial circumstances, exert constant influence and must be taken into account; they are represented in the box underneath the model. (For example, budget shortfalls may force a district to cut back on services that have significant effects on students and families.)

Element 1: Structures and Roles

Are they established and working as intended?

A principal goal of PERAA was to establish clearer functions and lines of authority, on the theory that a leaner, less complicated structure would lead to better coordination and more efficient operations, which would in turn promote improvements in teaching and learning. To assess this element, evaluators should document that the new offices were in fact established with clear roles and responsibilities, that they are operating as intended in the legislation, and that the changes were sufficient to eliminate major problems and create the momentum for ongoing improvement. If

the District makes additional changes to those structures (e.g., as it has done by deciding not to have an ombudsman), perhaps even in response to the evaluation, those changes, in turn, should be assessed. (Chapters 4 and 6 describe what had been done by the time this report was being written, but a formal evaluation would entail review of multiple perspectives, close analysis of numerous documents, interviews with individuals throughout the system, and other data collection that were not part of the committee’s task.)

Element 2: Strategies

Are they evidence-informed, of sufficient scope and quality, and implemented well?

Establishing new structures and relationships is not the same as developing approaches to improve the system; to produce the intended outcomes for students, the offices created by PERAA would have to initiate strategies that effectively address critical needs facing the schools. Thus, a second focus of the evaluation program will be to identify and describe how education leaders have set out to accomplish the stated reform goals, in the context of the new functions and lines of authority.

Specifically, evaluators will need to focus on whether DC’s education officials are doing what they said they would do and how well they are doing it. We are guided by the abundant research on school reform indicating that education strategies can founder if they are not based in research and practice or if a promising practice is not implemented well (e.g., Aladjem and Borman, 2006; McLaughlin, 1990; Ruiz-Primo, 2006). Studies of the fidelity with which reforms are implemented reveal important differences in the way they are viewed and understood (Hedges and Schneider, 2005). Effective implementation means understanding the rationale and key features of a program or strategy, and achieving a balance between adherence to these features and adaptation to the unique features of a school, a district, or the students. Thus, the evaluation program should assess the extent to which the research and practice evidence supports the choice of specific strategies and determine whether those strategies are being faithfully and effectively implemented.

Element 3: Conditions for Student Learning

Are conditions improving overall and across diverse schools and students?

For strategies to improve student outcomes, such as academic achievement or high school graduation rates, or to reduce gaps in achievement among student subgroups, another step is needed—the new structures and

strategies, once in place, have to lead to improved conditions for student learning. Many conditions are related to student learning:

- core conditions, such as having effective teachers and principals;

- the articulation of clear content and performance standards aligned with curriculum and instruction;

- school climate (e.g., safety, a focus on academic goals and a constructive working environment for teachers);

- the availability of art and music instruction, physical education, and other extracurricular opportunities; and

- clean, safe, and properly equipped facilities.

Changes in conditions are a critical intermediate step between the implementation of strategies and the achievement of outcomes. Improved conditions for learning are the critical means by which reforms influence student outcomes, and monitoring them is an integral aspect of the proposed evaluation program. The monitoring should be done in individual classrooms and schools, but it will also be important to look at distributions of conditions across the entire system and how they vary by neighborhood, type of school, and subgroups of students. Which specific conditions a district should monitor, and how, are important questions; we discuss below the process of setting specific evaluation priorities and our recommendations to the District.

Element 4: Outcomes

Are valued outcomes being attained overall and for diverse schools and students?

Improvements to particular conditions for learning are valuable because they may lead to improvements in outcomes for the system and for students. Although test scores and high school completion or dropout rates are often considered the only or most important outcome, there are many other important outcomes. Grade retention, college entrance and completion, civic participation, and successful entry into the labor market provide fuller information about students’ trajectories. The development of technical and vocational skills is also important. As with achievement data, it will be important to examine how equitably outcomes are being achieved. Some of these other outcomes may be included in the information system the District is already collecting or developing, but many—particularly post-K-12 outcomes, such as the need for remediation for college freshmen and on-time college graduation—will require new data systems. (See Chapter 4 for information about the District’s data collection.)

The proposed evaluation program will serve two interrelated purposes: to determine whether the provisions of the legislated reform have been implemented as intended and to evaluate whether the short- and long-term goals of the reform are being achieved. Thus, the framework mirrors our earlier distinction among PERAA’s intent, how it has been implemented, and its short- and long-term effects. Treating these three components separately could seem to imply that they occur in a linear fashion, and can be examined in order. In practice, of course, this is not the case, and evaluation activities cannot be organized quite so neatly. For example, comprehensive study of a strategy (e.g., the teacher evaluation system) would need to include examination of the conditions it was designed to create (e.g., presence of better teachers, higher teacher satisfaction), and, ultimately, student outcomes (e.g., whether teachers who receive high ratings have a measurable effect on students’ test scores).

Moreover, although the framework is a simple depiction of the primary components of a reform, the basic questions to be asked under each of the four elements will, in practice, need to be answered using many different study designs, data collection methods, and types of analysis. Thus, the evaluation framework is intended to address the kinds of questions usually posed by policy makers, system administrators, and the community at large, and answering these questions requires a combination of tools.

A Combination of Ongoing Indicators and In-Depth Studies

One primary function of evaluation is to collect data to monitor the basic status of students, staff, resources, and facilities. Some of this information is collected as part of the internal management that the system itself undertakes (and assessing the quality of that internal management is also a function of the evaluation); other information that is needed may not be. Another function is to probe more deeply into specific questions, which may require not only supplemental data collection, but also more sophisticated analysis than is usually a part of regular data collection.

Indicators are measures that are used to track progress toward objectives or monitor the health of a system. In education, for example, school districts typically collect average scores on a standardized reading assessment for each grade to monitor how well students are meeting basic benchmarks as they progress in reading. Other commonly used indicators include high school graduation rates, rates of truancy, ratios of teachers to students, and

per-pupil expenditures, as well as measures of less quantifiable factors, such as teachers’ and students’ attitudes. Indicators—literally signals of the state of whatever is being measured—can cover outcomes, the presence or state of particular conditions, or the effectiveness of management approaches. Outcome indicators might be used to make overall evaluations, while management indicators would be used to fine-tune the operation of the system. Indicators are generally collected on a regular basis and in a way that allows for comparisons over time. Thus, indicators can be useful for documenting trends (positive or negative) over time; documenting trends within relevant subgroups (through disaggregated data); drawing attention to significant changes (typically sharp increases or decreases), which may indicate areas of concern or success; flagging relationships among indicators (e.g., a correlation between measures of a strategy’s implementation and an outcome); developing hypotheses for further study (e.g., through observations of the co-occurrence of two or more phenomena); and providing early warnings of problems (e.g., students who struggle to meet benchmarks in elementary school are more likely to struggle or drop out during high school).

As we discussed in Chapter 6, the District currently does collect much of this data in SchoolStat, the District’s management indicator system that is part of CapStat, a citywide performance monitoring system. The first steps in the committee’s proposed evaluation program will be to examine thoroughly the data already collected regularly and to assess the quality of the measures and whether they yield the information needed for evaluation purposes.

Ongoing indicators provide a general picture of a system and identify patterns that warrant further investigation, but in-depth studies are needed to provide finer resolution. We use the term “in-depth studies” to include any additional undertaking, such as analysis of existing data or collection of new data using focus groups, observations, or surveys. Such studies could be designed to describe practices, examine relationships, or determine the effectiveness of particular practices. They might shed light on the causes of the findings from indicator data, explore potential reasons for disappointing outcomes, provide information to help improve existing strategies, or help explain why some strategies appear to be working better in some schools than in others. They might require significant resources and intrusion into classrooms or be comparatively simple and inexpensive. They are important because they are the means by which evaluators can answer policy makers’ questions about the effects of policies, practices, and reforms.

The design of an in-depth study and its data collection methods depends in large part on the questions being asked. Some studies seek answers

to descriptive questions about what is happening in schools (for example, what is being taught in certain grades or subjects). Descriptive studies can also examine relationships, asking whether there are differences across schools, for example, or across different groups of teachers or students. Some studies seek answers to explanatory questions, such as how particular student outcomes occurred. A third type of question aims to attribute an outcome to a particular policy or practice, asking, “Did this particular policy or practice cause student outcomes to improve?”

For example, implementation studies examine how well (that is, how consistently, effectively, and efficiently) a district has put into action the improvement strategies it has chosen. Such studies might assess the implementation of new roles and structures (Element 1 in our framework) or strategies for improving education (Element 2), as well as relationships to education conditions (Element 3) and system and student outcomes (Element 4). Implementation studies do not generally provide evidence of causality—that is, they do not provide evidence that a particular strategy led to a particular outcome. To obtain information on causality requires an impact study and generally involves more sophisticated and costly data collection activities and study designs (e.g., randomized trials) to determine the impact of a specific intervention.

Whatever questions they ask, in-depth studies can and should be designed rigorously to provide complete and accurate information. For descriptive studies, for example, if a researcher wishes to generalize to a larger population, rigor would include selecting study respondents who will produce unbiased information through stratified random samples and using data collection methods that ensure high response rates.

Studies that address causal questions have to be designed especially carefully to rule out alternative explanations of outcomes. This can be done through randomly assigning subjects (schools, teachers, or students) to different conditions or through other designs that eliminate alternative explanations of the outcomes when random assignment is not possible (e.g., regression discontinuity studies). For a full discussion of the relationship between evaluation questions and study designs, see National Research Council (2002).

The two components of the evaluation program—ongoing indicators and in-depth studies—interact with one another. Ongoing indicators may identify an area of focus for a special study, and special studies may point to new indicators that need to be added to the ongoing monitoring program. Both indicators and in-depth studies are expected to evolve, as different needs and issues emerge for the District. Although the evaluation program we propose will be independent, this evolution would be shaped to a significant degree by the concerns and priorities of DCPS and the broader community.

The way in which the results of both monitoring and in-depth studies are conveyed to stakeholders is critical to the value of the evaluation system. Reporting of student achievement results and some other kinds of information is a requirement of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act, with which most districts are in compliance, and many go beyond those requirements (Turnbull and Arcaira, 2009). The District already reports many sorts of information to the public. However, the primary information is not currently consolidated in a single report.

Recommendation 2 The Office of the Mayor of the District of Columbia should produce an annual report to the city on the status of the public schools, drawing on information produced by DCPS and other education agencies and by the independent evaluation program that includes

- summary and analysis of trends in regularly collected indicators,

- summary of key points from in-depth studies of target issues, and

- an appendix with complete data and analysis.

These data and analyses should be supplemented by an online data resource in a format that is easily navigated by users and can be updated more frequently. The annual report should be concise and easy for policy makers, program managers, and the public to use. This reporting would also be supplemented by the reports generated by the evaluators.

AN EXAMPLE OF INTEGRATING EVALUATION ACTIVITIES: IMPROVING TEACHER QUALITY

The committee’s proposed evaluation framework and the discussion above provide an overview of the primary elements of evaluation and the kinds of anlyses it would include, but they do not indicate in detail how these pieces would be integrated and how priorities for topics and studies will be established. For some areas, particularly operations and management, the relationship is fairly straightforward. For example, DC might monitor the efficiency of core operations using such measures as the average number of days it takes for a procurement process to be completed. If delays in the procurement of, say, textbooks, are a clear problem, the evaluators might conduct case studies to determine the cause of these delays. Monitoring the effectiveness of operations and using focused analysis to diagnose problems in this area is comparatively simple, but many evaluation questions are more complex.

Improving teacher quality is a primary strategy that DC has adopted as part of its implementation of PERAA, and it is arguably one of the most important responsibilities of any school district. Because it will therefore inevitably be a primary part of any evaluation of DC schools and because it is a very challenging area to evaluate, we examine this topic in detail as an illustration of how our evaluation framework would work.

The key question is whether the District is taking effective steps to hire and keep good teachers (as well as principals and administrators)—and to make sure that all schools have them. Improving the quality of DCPS’s teachers was a key element of the strategy of former chancellor Michelle Rhee: see Box 7-1.

As we discuss in Chapter 6, the research on teacher quality suggests that it is the product of many district and school strategies, including efforts to

- recruit and retain effective teachers and ensure that they are equitably distributed across schools;

- evaluate teachers’ effectiveness;

- provide professional support and development to all teachers, as well as targeted support for teachers who need it; and

- foster working conditions that support trust and collaboration among teachers.

More specifically, procedures that allow a district to make early offers to the teacher they wish to hire, for example, may make a significant difference in the quality of new teachers (Levin and Quinn, 2003; Liu et al., 2008, 2010; Murnane, 1991). Mentoring and support for new teachers during their first few years in the classroom may help a district retain the most promising novices, although recent evidence raises questions about the role of induction in retaining novice teachers overall (Glazerman et al., 2010a; Ingersoll and Kralik, 2004; Ingersoll and Smith, 2004). Working conditions in schools can strongly influence teachers’ decisions about whether to stay in particular schools. For example, teachers often value the support of a professional learning community more than salaries, and new teachers report that rules and practices in their schools affect their decisions about whether to stay in the field (Berry et al., 2008; Inman and Marlow, 2004; Johnson, 2004; McLaughlin, 1993; Mervis, 2010). Administrator leadership and support also appear to be important for teacher retention (Ladd, 2009). A teacher evaluation system that is perceived as rewarding highly effective teachers and providing learning opportunities (and, if necessary,

BOX 7-1

DCPS Strategies to Improve Teacher Quality: Example

A central goal of Chancellor Rhee’s reform strategy was to improve the effectiveness of DCPS teachers through performance-based accountability. A primary element of her approach was the establishment of a new evaluation system (IMPACT). Fifty percent of a teacher’s score comes from student achievement data, 40 percent from observations of teaching practice, and 10 percent from student outcomes for the school as a whole and teachers’ contributions to the school community. A new contract negotiated with the teachers union tied teacher salaries to teacher performance as measured by IMPACT, as discussed in Chapter 4.

To determine the likely effectiveness of the strategy, the evaluation should answer two key questions:

- How sound and well conceived is the strategy?

- How well implemented is the strategy?

Evaluating this strategy would first involve documenting any evidence from research and practice for the chosen strategy and for competing theories that might have been the basis for a different strategy. For example, some research may document the importance of objective measures of teacher quality, while other work may emphasize the importance of trust among teachers to improving educational outcomes. In that case, evaluators would need to ask whether performance-based accountability is at odds with the need to build trusting relationships with other staff and whether both are likely to be needed to achieve valued outcomes.

To answer the question on implementation, an evaluation might examine, for example, whether the strategy to evaluate teacher performance was reliable and understandable to participants. If the methods of linking student performance to teacher outcomes are not technically sound, if the observations of teachers are performed by individuals without the requisite expertise, or if the system is not adequately explained to the teachers, teachers might question the legitimacy of the system, which could undermine its effectiveness.

the basis for removing) for ineffective teachers also can contribute to the quality of the teaching force, according to some analysts (Gordon et al., 2006; Kane et al., 2006).

This knowledge base provides the basis for thinking about ongoing indicators that can be used to monitor the District’s strategies for fostering teacher quality and in-depth studies that would supplement the indicators.

A robust set of indicators will provide information on whether the quality of teachers improves over time and whether high-quality teachers

are equitably distributed across schools. That is, the indicators would include measures of the characteristics of the teachers themselves and of the systems used to improve the quality of the teacher workforce.

There are several possible measures of teacher quality that could be used. The percentage of DC teachers who are “highly qualified” as defined by NCLB is easy to obtain. However, this definition has been criticized. Researchers have found that the vast majority of teachers appear to meet the criteria—94 percent nationwide in 2006-2007, according to one study—and also that states differ substantially in how they measure teacher quality for the purpose of meeting NCLB requirements (Birman et al., 2009; see also Berry, 2002; Lu et al., 2007; Miller and Davison, 2006). At present, it provides at least a starting point on which to build, especially in DC, which has the lowest percentage of classes taught by a teacher defined as highly qualified under NCLB in the nation (in comparison with states, not school districts) (Birman et al., 2009). The basic requirements are that teachers have a bachelor’s degree and be fully licensed by a state, and be able to “prove that they know each subject they teach”; many states have added additional requirements (U.S. Department of Education, 2004, p. 2).1 The NCLB definition might be viewed at present as necessary but not sufficient, because it sets a low bar and allows states substantial discretion in setting their own bars. Researchers are engaged in pursuing other means of measuring teacher quality (Birman et al., 2009).

The purpose of seeking high teacher quality is to improve student outcomes. However, there is currently limited evidence that teachers with master’s degrees or state certification do produce higher student outcomes than other teachers (Goldhaber and Brewer, 1996; Rockoff, 2004).2 Measures for which there is empirical evidence of a modest relationship to student outcomes include years of experience and certification by the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS), and holding a degree in mathematics (for math teachers) (Huang and Moon, 2009; Kane et al., 2006; National Research Council, 2008; Rice, 2010; Wayne and Youngs, 2003). Measures of teacher effectiveness, including using student achievement data to determine teachers’ “value added” and rigorous instruments for observ-

_______________

1DC’s definition, which elaborates several ways in which teachers can demonstrate mastery of core subjects, can be found at http://newsroom.dc.gov/show.aspx?agency=sboe§ion=2&release=13083&year=2008&month=3&file=file.aspx%2frelease%2f13083%2fFinal_ HQT_resolution.pdf [accessed December 2010].

2One reason that the evidence about the benefits of these qualifications is not strong may be that the categories are extremely broad. That is, programs that award master’s degrees to teachers vary so much in their requirements, admissions standards, and quality that any benefits conferred by excellent programs would be obscured in the data by the lack of benefits conferred by other programs. Similarly, states’ requirements for licensure vary and are not generally high: for a full discussion of these issues, see National Research Council (2010).

ing teachers, also hold promise for understanding and improving teacher quality. However, many technical issues related to use of these methods for making individual personnel decisions have not yet been resolved (Baker et al., 2010; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, 2010; Glazerman et al., 2010b; Kupermintz et al., 2001; McCaffrey et al., 2004; Rothstein, 2011).

It may also be useful to track how long effective teachers stay in the system (i.e., their retention rates) and what schools and neighborhoods they serve. In general, schools in high-poverty neighborhoods have greater difficulty than other schools in attracting and retaining the highest quality teachers (Hirsch, 2001; Rice, 2010). For these kinds of measures, data from administrative records (e.g., teacher qualifications and other characteristics) are another important resource, as are the results of teacher evaluations (Stanton and Matsko, 2010).

The District already is collecting many of these indicators, and, as we note above, a comprehensive examination of the existing data collection activities is a first task of the evaluation program. We also note that indicators of teacher effectiveness that rely on student achievement or teacher observations will need to be reconsidered as knowledge about the characteristics of the measures improves. Indeed, in-depth studies should include internal analyses of the validity of measures of teacher quality, and those measures should be improved as needed.3

Ongoing indicators related to teacher quality that can produce the kinds of information the District needs fall into two categories: those that measure characteristics of the teachers themselves and those that measure teacher recruitment, retention, and support for teachers.

A range of measures would be valuable as indicators of teacher quality, including

- number and percentage of highly qualified teachers under NCLB, on a districtwide basis and by school characteristics, such as the socioeconomic status of the students;

- number and percentage of teachers with experience teaching at the grade level and subject of current teaching assignment, on a districtwide basis and by school characteristics, such as the socioeconomic status of the students;

_______________

3The validity of a measure is a way of describing the extent to which it accurately measures what it is intended to measure and supports accurate inferences about the question the measure was designed to answer. In the context of teacher quality, there is debate over the extent to which available measures actually capture characteristics that make a teacher effective.

- number and percentage of teachers who score at each performance level (using a valid evaluation tool that includes measures of student learning), on a districtwide basis and by school characteristics, such as the socioeconomic status of the students;

- number and percentage of teachers with relevant background characteristics, such as college grade point average, and scores on certification tests, such as PRAXIS, on a districtwide basis and by school characteristics, such as the socioeconomic status of the students; and

- number and percentage of teachers with NBPTS certification, on a districtwide basis and by school characteristics, such as the socioeconomic status of the students.

Recruitment, Retention, and Professional Support

Similarly, a range of measures would be valuable as indicators of teacher recruitment, retention, and professional support:

- number and percentage of high-quality (by district definition) teachers retained, on a districtwide basis and by school characteristics, such as the socioeconomic status of the students;

- timely and efficient recruitment process, as measured by the percentage of offers to prospective teachers and principals before the end of the school year;

- percentage of novice teachers who receive mentoring or other induction supports such as reduced teaching load, common planning time, orientation seminars, or release time to observe other teachers;

- percentage of teachers who participate in high-quality professional learning opportunities, that is, those that are sustained, content-focused, and involve participation with colleagues;

- percentage of teachers who participate in high-quality professional learning opportunities for high-need subjects and populations; and

- percentage of teachers who report positive working conditions and professional learning environment in their schools.

The indicators detailed above would provide necessary baseline information about teachers’ characteristics and the conditions in which they work, as well as about the effectiveness of the DCPS’s strategies for raising the overall level of teacher quality. But making good use of this information would require further study, particularly in two areas.

First, which measures of teacher quality provide the most accurate and useful information? Studies of the validity and reliability of using student outcome data and teacher observations to measure teacher effectiveness, as is currently done in the District under IMPACT, will be a valuable contribution to the evolving research in this area.4 Studies of other teacher quality measures, such as NBPTS certification, possession of advanced degrees, scores on teacher assessments, and novice status will also be valuable as the District continues to refine its means of identifying the most effective teachers. Researchers have examined these measures in other contexts, and it will be useful to explore the applicability of their findings to the DC context.

Second, what strategies are working to attract effective teachers to the District and retain them? What can be concluded about why good teachers do or do not stay in DC schools and whether they leave teaching or just leave DC schools? Answering these questions entails study of the effectiveness of the city’s primary strategies for hiring and retaining high-quality teachers and supporting their professional development. Such in-depth studies could include

- evaluation of recruitment practices, including interviews with applicants who accepted and declined offers regarding their experiences with the recruitment process;

- evaluations of the quality of mentoring and coaching for novice teachers to determine the skills of coaches and the perceived usefulness for novice teachers;

- study of changes teachers make in their practice in response to evaluations that use student achievement and observations to assess teacher effectiveness;

- follow-up studies of teachers who left the school system to determine whether they moved to a neighboring district and why they moved;

- study of the costs and benefits of different approaches to professional development (e.g., coaching or academic courses); and

- study of the features of the work environment for teachers, perhaps involving surveys and focus groups of teachers, observations to compare high- and low-performing schools, and benchmark schools outside the system.

_______________

4Many organizations are currently supporting research on teacher quality, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (see http://www.gatesfoundation.org/highschools/Documents/met-framing-paper.pdf [accessed January 2011]); Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. (see http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/Newsroom/Releases/2010/Education_wins_12_10.asp [accessed January 2011]); the American Institutes for Research (see http://www.air.org/expertise/index/?fa=view&id=95 [accessed March 2011]); and RAND Corporation (see http://www.rand.org/topics/teachers-and-teaching.html [accessed March 2011]).

With a combination of the ongoing indicators and focused in-depth studies discussed above, it would be possible to examine relationships across the elements of reform in our proposed framework. For example, such evaluations could examine whether the strategies the DCPS has chosen to recruit and retain effective teachers (Element 2 in our framework) are strategies for which there is empirical and practical evidence; whether those strategies are related to conditions for learning in the way that was intended (Element 3); and whether any changed conditions are related to improved outcomes for students (Element 4).

A combination of ongoing indicators and in-depth studies can also be used to assess the evidence base for specific approaches the DCPS is using to attract and keep effective teachers in schools in the highest poverty areas—which would include assessing the measures of quality on which they relied; whether the numbers of highly effective teacher in those schools did increase; and whether educational experiences improved in any measurable way in those schools. The last link is to determine whether those improvements resulted in higher achievement or other valued outcomes for the students in those schools.

DETERMINING PRIORITIES FOR EVALUATION

In a world without time and resource constraints a full evaluation program would supply information about every aspect of what school districts do. In reality, though, priorities are needed, and the District will need to develop the portfolio of data collection and analysis that will best meet its needs and answer its most pressing questions and support policy and practice decisions. Developing a comprehensive set of indicators and an evaluation agenda is a long-term endeavor. What are the highest priorities for the District of Columbia? What areas should be the first priority for the evaluation program? These questions ultimately should be answered by city and education leaders and the broader community they serve, but we offer some structures for those decisions.

First, we stress that the identification of specific indicators and studies with which the actual evaluation will begin should be based on (1) a systematic analysis of the indicators already available and (2) systematic analysis of the data available regarding important issues for the city’s schools, combined with a process of exploration and priority-setting that would involve both city and school leaders and other stakeholders, such as teachers, parents, and other interested city residents. We expect that once a stable set of long-term indicators, combining those already collected by the District and other new measures, is in place, a series of in-depth studies will address a range of specific issues over time.

Our framework is intended above all to facilitate an evaluation that,

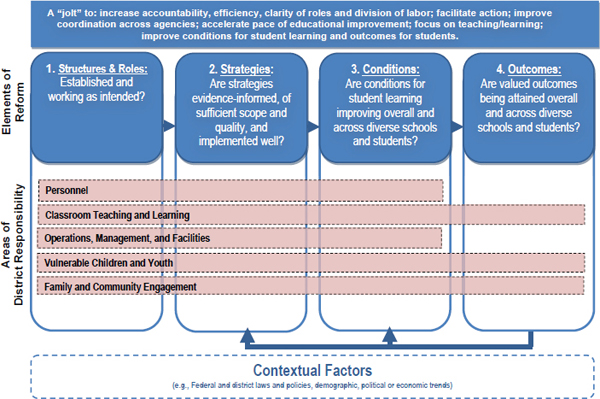

however lean resources may require it to be, nevertheless addresses the most important aspects of a school system. That is, it must address the elements of reform (the selection of strategies, their implementation, the conditions they create, and their outcomes), and it must also address the primary substantive responsibilities a district has. We discuss in Chapter 6 five broad categories of responsibility for a school district: we believe any evaluation program must address each of these categories if it is to provide a comprehensive overview of the state of the District’s schools. These two mandates can be compared to the warp and woof in a piece of fabric, as shown in Figure 7-2: the elements of reform and the broad evaluation questions pertaining to them are depicted in the vertical boxes; the substantive areas of responsibility are depicted with shaded horizontal bands. A comprehensive evaluation program would include indicators and studies to address critical evaluation questions about each of the elements of reform (depicted in Figure 7-1, above) and about a school district’s substantive areas of responsibility.

Of course, it is not necessary or possible to address all possible questions related to each of these areas at once; rather, we emphasize that no one of these areas should be neglected in the long-term evaluation program.

Primary Responsibilities to Be Evaluated

As we discuss in Chapter 6, a school district’s responsibilities to students, families, and the community cover:

- personnel (teachers, principals, central office);

- classroom teaching and learning;

- vulnerable children and youth;

- family and community engagement; and

- operations, management, and facilities.

Each of these categories encompasses many specific responsibilities and thus entails many possible evaluation questions.

Our evaluation framework is designed to ensure that there is balance in the detailed program of indicators and in-depth studies. Examples of the sorts of questions one might ask for each of these areas are shown in Table 7-1. These examples do not have special importance: we offer them simply to illustrate the distinctions among questions that address the strategies the District has selected, the conditions for learning they are designed to affect, and the outcomes that changes in those conditions might have with respect to each of the areas of responsibility.

TABLE 7-1 Evaluation Questions for DC: Examples

| Category of Responsibility and Possible Focus | Questions on Structures and Strategies | Questions on Conditions | Questions on Outcomes | |

| Personnel: Principal Quality | What methods are used to evaluate principals? Does the method discriminate among effective and ineffective principals in a valid and reliable way, given DCPS objectives? Does it work equally well for principals at all levels (elementary, middle, and secondary)? | Is the number of principals who are rated as effective increasing, and are they equitably distributed? | Are students in the schools that have principals rated as highly effective under the new system improving in their academic performance, in comparison with students in schools that do not have such principals? | |

| Classroom Teaching and Learning: Alignment Between Curriculum and Professional Development | Do professional development plans and activities address the learning goals that are articulated in the curriculum? | Do teachers who have received professional development demonstrate increased use of the content knowledge and practices that target curricular goals? | Do the students of teachers who have received professional development demonstrate greater mastery of curricular goals? | |

| Vulnerable Children: Special Education | To what extent does DCPS identify and serve students with disabilities in an appropriate, timely, and cost-effective manner (consistent with the core provisions of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act)? | To what extent are special education students served in the least restrictive settings and receiving educational and related services that are appropriate and evidence based? | To what extent are students with disabilities, especially those with learning disabilities and behavioral disorders, meeting the goals identified in their individual education plans (IEPs), and are IEP goals high enough to narrow the achievement gap between students who do and do not have disabilities? | |

| Category of Responsibility and Possible Focus | Questions on Structures and Strategies | Questions on Conditions | Questions on Outcomes | |

| Family and Community Engagement: Communication | To what extent does DCPS have structures in place that allow parents, legal custodians, and other community residents to voice their concerns, seek remedies to problems, and make general recommendations to the school system? | To what extent do parents and others throughout DC use these structures regularly? Does the use vary across neighborhoods, grade levels, etc.? | To what extent do parents and others report that they are heard and valued? Do parents report greater involvement and satisfaction with their children’s education over time? Does this involvement vary across neighborhoods and schools? | |

| Operations, Management, and Facilities: Technology | To what extent are structures in place to coordinate technology in the schools, such as internet access and computer hardware and software, and to ensure that those resources are equitably distributed? | To what extent do schools in all wards and neighborhoods have sufficient up-to-date and properly maintained computer systems, as measured by the ratio of students to computer stations? | Are students meeting benchmarks in the academic standards that include technical skills, such as internet searching and graphic functions? | |

Criteria for Setting Priorities

The examples in Table 7-1 are only a few of the many empirical questions that can be asked, and District leaders, in collaboration with the evaluators, will need to make choices. Policy makers will seek information to help them determine whether to continue or abandon a policy or practice. Program managers will want to know how to improve operations or services. Practitioners will be interested in specific techniques that they might use to achieve program goals, and members of the public will ask a range of questions not only about the school system but also about issues such as the wise use of tax revenue and the level of local participation in decisions (Weiss, 1998).

Analysis of costs and benefits will be a key part of the process of identifying the easiest problems to tackle. All things being equal, it makes sense to address first problems that might be solved easily or at relatively low cost, while laying the foundation for more difficult issues. For example, a problem with the distribution of textbooks or transportation is likely to be quick and easy to solve, in comparison with, say, the challenge of improving teacher quality.

High priority should be given to core problems facing practitioners and decision makers and the strategies that have been undertaken to address them (Roderick et al., 2009). Core problems often will be identified through the analysis of student performance indicators. Significant changes in student outcomes will always warrant the attention of evaluators, as will poor outcomes for specific grade levels, or for subgroups of the student population or for schools in particular neighborhoods.

Evaluating the reform strategies undertaken to address core problems also should be a major priority. For DCPS, a primary reform strategy has been upgrading the qualifications and effectiveness of human resources and strategies to improve teacher quality, so this is one obvious evaluation priority. But other strategies should also be included in the evaluation program.

Another obvious priority would be conditions that have historically been significant sources of problems for DC. One example, as we discuss in Chapter 6, is special education, which has been a big drain on the DCPS budget without providing adequately for students’ needs. Areas of success, whether identified in DC or through external research, should also be included in the evaluation program, so that they can be replicated, if possible.5 Another area for inclusion is problems for which external research suggests likely solutions.

These criteria are starting points: they should be used to stimulate public conversation among stakeholders. These conversations should lead to refinements and revisions of the way in which each of the broad categories in our evaluation framework will be considered and the specific questions that are important to answer. We emphasize that these conversations, and the process of establishing priorities for the evaluation program, should be much more than public relations exercises. The evaluation studies should be firmly grounded in the strongest scientific standards for data collection and analysis, but the information collected will be used for many purposes. It can be assumed that all stakeholders share the goal of applying information to improve the schools in technically sound ways, but the evaluation studies must be responsive to the different questions asked by different

_______________

5The U.S. Department of Education’s Doing What Works web page is one resource for information about research-based practices, see http://dww.ed.gov/ [accessed January 2011].

groups. A delicate balance will be needed between the competing pressures of budget, practicality, scientific purity, and political exigencies. An independent funding and management structure should ensure not only that evaluation activities are conducted according to the highest professional standards, but also that they continuously produce information that meets the needs of those working in the school system, city leaders, and the public. Stability and independence will be essential to an effective evaluation program, and the precise means of ensuring both will need to be determined by the local institutions and entities that become involved.

ESTABLISHING LONG-TERM EVALUATION CAPACITY

Building and maintaining a set of high-quality indicators, designing in-depth studies that address pressing issues, and organizing the presentation and dissemination of findings so that all stakeholders can use them will require deliberate and skillful management. We have argued that periodic attempts to evaluate the effects of PERAA and the status of the public schools will provide neither the breadth nor depth of information needed. The scale and scope of the evaluation program we recommend calls for a gradual increase in both data collection and analysis activities over a period of years.

The technical and professional challenges of building and maintaining the infrastructure needed for an indicator system capable of supporting direct analysis of large-scale datasets as well as periodic studies of key issues and topics include

- establishing procedures for ensuring that researchers and stakeholders collaborate in research agenda setting and planning activities;

- establishing agreements with schools and other entities for accessing data and drawing study samples;

- negotiating agreements about the ownership and use of data;

- setting procedures for the review and reporting of research findings to stakeholders such as program managers, practitioners, policy makers, the public, and the media;

- identifying principal investigators and consultants with the expertise to carry out specific analyses and in-depth studies; and

- creating research advisory structures, both to ensure rigorous designs and to review methodological and reporting strategies.

The usefulness of any school district’s evaluation program hinges on its credibility. To be trusted and valued, the evaluation program must focus on issues the community and education leaders view as important. To guard against the natural tendency of any organization to seek data that support

existing programs, it must also be independent. Both the questions asked and the interpretation of the information collected need to reflect the highest levels of impartiality.

There are few examples of research organization and management that have addressed such an array of challenges. Thus, if it is to implement an evaluation program that addresses these challenges and meets the goals we have described, the District will need both to benefit from experiences in other cities and to capitalize on local institutions and expertise to craft a sustainable structure.

Evaluation Programs: Resources and Examples

Districts and states have paid increasing attention to collecting data and using it to guide planning and decision making, partly in response to NCLB, which includes many requirements for assessing and reporting on student achievement and other questions. Most states and school districts are in compliance, and the U.S. Department of Education has awarded grants to districts for the purpose of improving the quality of their data collection and analysis (Stecher and Vernez, 2010). The Data Quality Campaign, a foundation-funded partnership of numerous nonprofit education organizations, has taken the lead in advocating for and supporting jurisdictions in the use of data to improve student achievement.6 In a study of data collection in four districts (DCPS, Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago) commissioned for this project, Turnbull and Arcaira (2009) found that all had expanded on the data requirements of NCLB. For example, she found that all four have begun monitoring “leading” indicators, which allow them to identify potential problems at an early stage and to collect more detailed information about school climate and other areas using qualitative data, such as survey responses.

The Consortium on Chicago School Research (CCSR) performs many of the research functions that are important for school districts, and it is an early example of a structure for providing independent information to support a district’s efforts to improve. This consortium, which includes researchers from the University of Chicago, the school district, and other organizations, was formed in 1990 to study reform efforts in the city’s public schools, following legislation that decentralized their governance.7

CCSR maintains a data archive that includes student test scores, administrative records, and grade and transcript files, as well as other data such as census and crime information and qualitative information from annual

_______________

6For more information, see http://www.dataqualitycampaign.org/ [accessed November 2010].

7For information about CCSR, see http://ccsr.uchicago.edu/content/index.php [accessed November 2010].

surveys of principals, teachers, and students. (CCSR also collects teacher assignments, samples of student work, interview and classroom observation records, and longitudinal case studies of schools.) CCSR has produced a significant library of studies and special reports, which, although they are specific to Chicago, have been influential nationally. CCSR has also been noted for its success in engaging the community (Turnbull and Arcaira, 2009).

New York City and Baltimore also have comparable research structures in place—though each has its own features: see Boxes 7-2 and 7-3 for further information on these evaluation and research structures.

BOX 7-2

Baltimore Education Research Consortium

Founded in 2007, the Baltimore Education Research Consortium (BERC) is a partnership between Baltimore City Public Schools (BCPS) and education researchers at Johns Hopkins University and Morgan State University (see http://baltimore-berc.org/ [accessed November 2010]). BERC’s activities are authorized by an executive committee of nine voting members representing the university, BCPS, and other community partners. The consortium is funded by a number of private foundations, including the Open Society Institute and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. BERC conducts research on education policies and provides data to assist BCPS in making policy decisions. Although the consortium is independent of BCPS, it works with the district to develop a research agenda and welcomes comments from BCPS leaders prior to releasing any studies.

BOX 7-3

Research Alliance for New York City Schools

In 2008, New York University launched the Research Alliance for New York City Schools (RANYCS) (New York University, 2010) to provide valid and reliable to the New York City Department of Education. RANYCS is independent of the department: its operations, financing, and research agenda are guided by a governing board, whose members include leaders of local civic organizations, foundations, as well as the chancellor of the schools and the president of New York University. The governing board outlines the general topics for the research agenda, and RANYCS develops a more specific research agenda in consultation with community leaders, practitioners, researchers, and the Department of Education.

A number of independent organizations have also developed approaches to assist districts in planning data collection and analyzing and using the results.8 The Broad Foundation uses an array of data to identify districts that have made significant progress in raising achievement and closing achievement gaps. The Council of the Great City Schools conducts detailed reviews of individual districts, at their request, analyzing quantitative and qualitative data and making tailored recommendations for improvement. The Central Office Review for Results and Equity, housed at the Annenberg Institute, also conducts reviews of individual districts, using data to assess how well they meet its criteria for effective district functioning:

- communicating big ideas,

- service orientation,

- data orientation,

- increasing capacity,

- brokering partnerships,

- advocating for and supporting underserved students, and

- addressing inequities.

Another model is the Strategic Education Research Partnership (SERP) (which began as an investigation of the potential for research to inform improvements in educational practice) (National Research Council, 1999; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2003).9 Although SERP was not a research enterprise of the sort we recommend, it offers useful principles: see Box 7-4. SERP paid explicit attention to the importance of collaboration between researchers and practitioners in the development of research questions, and it also placed a premium on identifying the strategic use of research findings in schools and classrooms.

It is difficult to generalize about what school districts do, and few models exist for the comprehensive approach to evaluation we believe is necessary. Researchers in Canada conducted a study of methods for measuring districts’ progress in reforming themselves in the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, Hong Kong, and New Zealand (Office of Learning and Teaching, Department of Education and Training, 2005). They found that although districts have many goals for their reform efforts, most rely heavily on measures of student achievement, primarily measures of “student performance on tests of literacy and numeracy, perhaps with science and social studies included in the mix” (p. 42). They note problems with the

_______________

8See Turnbull and Arcaira (2009) and the following websites: http://www.broadeducation.org/, http://www.cgcs.org/, and http://www.annenberginstitute.org/wedo/CORRE.php [accessed March 2011].

9For information about SERP, see http://www.serpinstitute.org/ [accessed November 2010].

BOX 7-4

Strategic Education Research Partnership

The Strategic Education Research Partnership (SERP) currently has relationships with Boston, San Francisco, and a group of four smaller, inner-ring suburban districts that are part of the Minority Student Achievement Network: Arlington, Virginia; Evanston, Illinois; Madison, Wisconsin; and Shaker Heights, Ohio. SERP represents a decentralized approach, with management decisions coming at the site level.

The priorities at each of the sites differ, but all programs follow a set of SERP principles:

- programs are to address the most urgent problems identified by the school district;

- an interdisciplinary team of researchers, developers, and practitioners are recruited by SERP;

- multiple approaches are taken simultaneously to solve the problem(s) identified by the school district;

- researchers and practitioners are involved throughout the entirety of a project; and

- all projects are evaluated rigorously.

The products produced by SERP thus far include assessments, instructional programs, pedagogical tools, and online professional development. Other school districts are using the organization’s findings to pursue their own projects. SERP is funded by a number of private foundations, individual donations, and federal agencies.

use of student test scores to monitor districts’ progress with broad reform goals, including limitations to the inferences that can be drawn from tests in a few subject domains, methodological concerns about how to include demographic data in analysis, and the difficulty of establishing causal links between specific practices or reform and information about student outcomes.

There is probably no one model that can readily be adopted in the District. The key to success for both the CCSR and SERP, for example, has been the organic way in which they came to exist and to evolve over time. These examples will be useful for DC to consider as it develops a specific structure for its own evaluation program. We hope that the city will collaborate with a variety of local organizations to establish a structure that will meet its needs, and will draw on analysis of the experiences of other districts, such as interviews with key figures in those districts, about how to manage and evaluate their reforms. Specifically, we believe that DC will

need to engage local universities, philanthropic organizations, and other institutions to develop and sustain an infrastructure for ongoing research and evaluation of its public schools that

- is independent of school and city leaders,

- is responsive to the needs and challenges of all stakeholders (including the leaders), and

- generates research that meets the highest standards for technical quality.

We believe that collaboration will be key to meeting these objectives.

School districts across the country have embarked on different paths in an effort to provide their students with an excellent and equitable education. Some, like the District of Columbia, have chosen dramatic “jolts” to the system that emphasize governance and performance measurement changes, while others have proceeded more incrementally toward the goal of bringing about significant change. Whatever the basic approach, there are numerous strategies by which the basic goals and reforms are implemented. For example, the District of Columbia’s strategy included the establishment of the office of chancellor of education with authority to develop ways to meet the goals laid out in PERAA. The individual first hired to fill that position chose to focus on improving human capital, but another chancellor might have chosen a different combination of strategies to meet the same goals, under the same or similar structural arrangements.

Our analysis of the origins, goals, and implementation of the DC reforms led to our recommendation for a comprehensive and sustainable program of evaluation. We note that many other districts have experimented with major reforms that require systematic evaluation. Just as there is no one model that can readily be adopted in the District, it is unlikely that the specific program adopted by DC will be instantly transferable to other school districts. Our hope, though, is for an evaluation program that is independent of school and city leaders, while remaining responsive to the needs and challenges of all stakeholders, that can generate research that meets the highest standards for technical quality. The independent program will necessarily involve collaboration with DCPS, OSSE, and other agencies because they will continue to conduct their own internal management and performance tracking functions. Their data will be useful to the evaluation program, just as new data and analysis provided by the evaluation will be useful to them.

Our evaluation framework is aimed at providing both the breadth

and depth of information that will assist policy makers and community members to assess whether PERAA and the education reform effort are achieving their goals and stimulating ongoing improvements. The evaluation program should be primarily focused on supplying timely and relevant information about the system, rather than definitive pronouncements on whether particular reforms are working or not. Objective evidence derived from multiple sources of data can be a tool for monitoring progress and guiding continuous improvement, and it is our hope that this model will be of use to districts around the country.

Aladjem, D.K., and Borman, K.M. (2006). Examining Comprehensive School Reform. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Baker, E.L., Bartson, P.E., Darling-Hammond, L., Haertel, E.H., Ladd, H.F., and Linn, R.L. (2010). Problems with the Use of Student Test Scores to Evaluate Teachers. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

Berry, B. (2002). What It Means to Be a Highly Qualified Teacher. Chapel Hill, NC: Southeast Center for Teaching Quality.

Berry, B., Smylie, M., and Fuller, E. (2008). Understanding Teacher Working Conditions: A Review and Look to the Future. Chapel Hill, NC: Center for Teaching Quality.

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (2010). Working with Teachers to Develop Fair and Reliable Measures of Effective Teaching. Seattle, WA: Author.

Birman, B.F., Boyle, A., Le Floch, K.C., Elledge, A., Holtzman, D., Song, M., et al. (2009). State and Local Implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act. Volume VIII—Teacher Quality Under NCLB Final Report. Jessup, MD: U.S. Department of Education.

Glazerman, S., Isenberg, E., Dolfin, S., Bleeker, M., Johnson, A., Grider, M., Jacobus, M., and Ali, M. (2010a). Impacts of Comprehensive Teacher Induction: Final Results from a Randomized Controlled Study. Jessup, MD: U.S. Department of Education.

Glazerman, S., Loeb, S., Goldhaber, D., Staiger, D., Raudenbush, S., and Whitehurst, G. (2010b). Evaluating Teachers: The Important Role of Value-Added. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Goldhaber, D.D., and Brewer, D.J. (1996). Why don’t schools and teachers seem to matter? Assessing the impact of unobservables on educational productivity. Journal of Human Resources, 32(3), 505-520.

Gordon, R., Kane, T.J., and Staiger, D.O. (2006). Identifying Effective Teachers Using Performance on the Job. The Hamilton Project Policy Brief No. 2006-01. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Hedges, L., and Schneider, B. (2005). The Social Organization of Schooling. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hirsch, E. (2001). Teacher Recruitment: Staffing Classrooms with Quality Teachers. Denver, CO: State Higher Education Executive Officers.

Huang, F.L., and Moon, T.R. (2009). Is experience the best teacher? A multilevel analysis of teacher characteristics and student achievement in low performing schools. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(3), 209-234.

Ingersoll, R.M., and Kralik, J.M. (2004). The Impact of Mentoring on Teacher Retention: What the Research Says. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States. Available: http://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/50/36/5036.pdf [accessed March 2011].

Ingersoll, R.M., and Smith, T.M. (2004). Do teacher induction and mentoring matter? NASSP Bulletin, 88(638), 28-40.

Inman, D., and Marlow, L. (2004). Teacher retention: Why do beginning teachers remain in the profession? Education, 124(4), 605.

Johnson, S.M. (2004). Finders and Keepers: Helping New Teachers Survive and Thrive in Our Schools. Indianapolis, IN: Jossey-Bass.

Kane, T.J., Rockoff, J.E., and Staiger, D.O. (2006). What does certification tell us about teacher effectiveness? Evidence from New York City. Economics of Education Review, 27(6), 615-631.

Kupermintz, H., Shepard, L., and Linn, R. (2001). Teacher Effects as a Measure of Teacher Effectiveness: Construct Validity Considerations in TVAAS (Tennessee Value-Added Assessment System). Los Angeles: University of California.

Ladd, H.F. (2009). Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Working Conditions: How Predictive of Policy-Relevant Outcomes? Working Paper #33. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Levin, J., and Quinn, M. (2003). Missed Opportunities: How We Keep High-Quality Teachers Out of Urban Classrooms. New York: The New Teacher Project.

Liu, E., Rosenstein, J.G., Swan, A.E., and Khalil, D. (2008). When districts encounter teacher shortages: The challenges of recruiting and retaining mathematics teachers in urban districts. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 7(3), 296-323.

Liu, E., Rosenstein, J.G., Swan, A.E., and Khalil, D. (2010). Urban Districts’ Strategies for Responding to Mathematics Teacher Shortages. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

Lu, X., Shen, J., and Poppink, S. (2007). Are teachers highly qualified? A national study of secondary public school teachers using SASS 1999-2000. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 6(2), 129-152.

McCaffrey, D.F., Koretz, D.M., Lockwood, J.R., and Hamilton, L.S. (2004). Evaluating Value-Added Models for Teacher Accountability. Pittsburgh, PA: RAND Education.

McLaughlin, M. (1990). The Rand change agent study revisited: Macro perspectives and micro realities. Educational Researcher, 19(9), 11-16.

McLaughlin, M. (1993). Teachers’ Work: Individuals, Colleagues, and Contexts. New York: Teachers College Press.

Mervis, J. (2010). What’s in a number? Science, 330(6004), 580-581.

Miller, K.W., and Davison, D.M. (2006). What makes a secondary school science and/or mathematics teacher highly qualified? Science Educator, 15(1), 56-59.

Murnane, R.J. (1991). Who Will Teach? Policies That Matter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

National Research Council. (1999). High Stakes: Testing for Tracking, Promotion, and Graduation. J.P. Heubert and R.M. Hauser (Eds.). Committee on Appropriate Test Use. Board on Testing and Assessment. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

National Research Council. (2002). Scientific Research in Education. Committee on Scientific Principles for Education Research. R.J. Shavelson and L. Towne (Eds.). Center for Education. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

National Research Council. (2008). Assessing Accomplished Teaching: Advanced-Level Certification Programs. M.D. Hakel, J.A. Koenig, and S.W. Elliott (Eds.). Committee on Evaluation of Teacher Certification by the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. Board on Testing and Assessment. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. (2010). Preparing Teachers: Building Evidence for Sound Policy. Committee on the Study of Teacher Preparation Programs in the United States. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2003). Engaging Schools: Fostering High School Students’ Motivation to Learn. Committee on Increasing High School Students’ Engagement and Motivation to Learn. Board on Children, Youth, and Families. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

New York University. (2010). The Research Alliance for New York City Schools, NYU Steinhardt. Available: http://steinhardt.nyu.edu/research_alliance/ [accessed November 2010].

Office of Learning and Teaching, Department of Education and Training. (2005). An Environmental Scan of Tools and Strategies That Measure Progress in School Reform. Available: http://www.education.vic.gov.au/edulibrary/public/publ/research/publ/Scan_of_Tools_Measuring_Progress_in_School_Reform_2005-rpt.pdf [accessed March 2011].

Rice, J.K. (2010). The Impact of Teacher Experience: Examining the Evidence and Policy Implications. Brief No. 11. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Rockoff, J.E. (2004). The impact of individual teachers on student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Economic Review, 94(2), 247-252.

Roderick, M., Easton, J.Q., and Sebring, P.B. (2009). A New Model for the Role of Research in Supporting Urban School Reform. Chicago, IL: Consortium on Chicago School Research.

Rothstein, J. (2011). Review of Learning About Teaching: Initial Findings from the Measures of Effective Teaching Project. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center.

Ruiz-Primo, M.A. (2006). A Multi-Method and Multi-Source Approach for Studying Fidelity of Implementation. CSE Report 677. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing.

Stanton, L.B., and Matsko, K.K. (2010). Using data to support human capital development in school districts: Measures to track the effectiveness of teachers and principals. In R.E. Curtis and J. Wurtzel (Eds.), Teaching Talent: A Visionary Framework for Human Capital in Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Stecher, B.M., and Vernez, G. (2010). Reauthorizing No Child Left Behind: Facts and Recommendations. Pittsburgh, PA: RAND Corporation.

Turnbull, B., and Arcaira, E. (2009). Education Indicators for Urban School Districts. Washington, DC: Policy Studies Associates.

U.S. Department of Education. (2004). Fact Sheet: New No Child Left Behind Flexibility, Highly Qualified Teachers. Available: http://www2.ed.gov/nclb/methods/teachers/hqtflexibility.pdf [accessed November 2010].

Wayne, A.J., and Youngs, P. (2003). Teacher characteristics and student achievement gains. Review of Educational Research, 73(1), 89-122.

Weiss, C.H. (1998). Evaluation: Methods for Studying Programs and Policies (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.