2

Oral Health Status and Utilization

Many of the country’s most vulnerable populations face the greatest oral health needs and the largest barriers to accessing oral health care. Because oral health is inextricably linked to overall health, the effects of poor oral health are felt far beyond the mouth. Oral health providers, policy makers, and other stakeholders need to coalesce around a common ground of basic preventive strategies, health literacy, and quality of care principles to improve the oral health of the entire U.S. population.

This chapter begins with a discussion of the connection between oral health and overall health. Next, the chapter gives a brief overview of the oral health status and access to oral health care for the nation as a whole. The specific oral health needs and access issues for individual vulnerable and underserved populations follows. Finally, the chapter considers several barriers to improving access to oral health care (and ultimately, oral health status) including poor oral health literacy, inadequate use of preventive services, and relative lack of oral health quality measures. These barriers are briefly considered here, as a fuller discussion of literacy, prevention, and quality measures can be found in the IOM report Advancing Oral Health in America (IOM, 2011).

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN ORAL HEALTH AND OVERALL HEALTH

For people suffering from dental, oral, or craniofacial diseases, the link between oral health and general health and well-being is beyond dispute. However, for policy makers, payers, and health care professionals, a chasm

BOX 2-1

Dental, Oral, and Craniofacial

The word oral refers to the mouth. The mouth includes not only the teeth and the gums (gingiva) and their supporting tissues, but also the hard and soft palate, the mucosal lining of the mouth and throat, the tongue, the lips, the salivary glands, the chewing muscles, and the upper and lower jaws. Equally important are the branches of the nervous, immune, and vascular systems that animate, protect, and nourish the oral tissues, as well as provide connections to the brain and the rest of the body. The genetic patterning of development in utero further reveals the intimate relationship of the oral tissues to the developing brain and to the tissues of the face and head that surround the mouth, structures whose location is captured in the word craniofacial.

SOURCE: HHS, 2000b.

has divided them. Dental coverage is provided and paid for separately from general health insurance (see Chapter 5), dentists are trained separately from physicians (see Chapter 3), and legislators often fail to consider oral health in health care policy decisions. In effect, the oral health care field has remained separated from general health care. Recently, however, researchers and others have placed a greater emphasis on establishing and clarifying the oral-systemic linkages.

The surgeon general’s report Oral Health in America emphasized that oral health care is broader than dental care, and that a healthy mouth is more than just healthy teeth (see Box 2-1). The report described the mouth as a mirror of health or disease occurring in the rest of the body in part because a thorough oral examination can detect signs of numerous general health problems, such as nutritional deficiencies and systemic diseases, including microbial infections, immune disorders, injuries, and some cancers (HHS, 2000b). For example, oral lesions are often the first manifestation of HIV infection, and may be used to predict progression from HIV to AIDS (Coogan et al., 2005). Sexually transmitted HP-16 virus has been established as the cause of a number of oropharyngeal cancers (Marur et al., 2010; Shaw and Robinson, 2010). Dry mouth (xerostomia) is an early symptom of Sjogren’s syndrome, one of the most common autoimmune disorders (Al-Hashimi, 2001); xerostomia is also a side effect for a large number of prescribed medications (Nabi et al., 2006; Uher et al., 2009; Weinberger et al., 2010).

Further, there is mounting evidence that oral health complications not only reflect general health conditions, but also exacerbate them. Infections

that begin in the mouth can travel throughout the body. For example, periodontal bacteria have been found in samples removed from brain abscesses (Silva, 2004), pulmonary tissue (Suzuki and Delisle, 1984), and cardiovascular tissue (Haraszthy et al., 2000). Periodontal disease has been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes (Albert et al., 2011; Offenbacher et al., 2006; Radnai et al., 2006; Scannapieco et al., 2003b; Tarannum and Faizuddin, 2007), respiratory disease (Scannapieco and Ho, 2001), cardiovascular disease (Blaizot et al., 2009; Offenbacher et al., 2009b; Scannapieco et al., 2003a; Slavkin and Baum, 2000), and diabetes (Chávarry et al., 2009; Löe, 1993; Taylor, 2001; Teeuw et al., 2010).

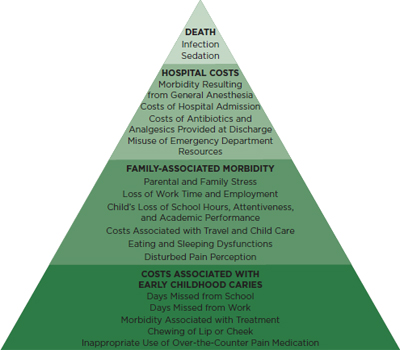

Poor oral health may be associated with several other types of morbidity (both individual and societal) including chronic pain, loss of days from school (Gift et al., 1992, 1993), and inappropriate use of emergency departments (Cohen et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2010). Oral health affects speech, nutrition, growth and function, social development, and quality of life (HHS, 2000b). In rare cases, untreated oral disease in children has led to death (Otto, 2007). The impact of poor oral health extends to a child’s family and community through lost work hours and the cost of hospital admissions, for example. Figure 2-1 illustrates the range of consequences of early childhood caries in a morbidity and mortality pyramid.

OVERVIEW OF ORAL HEALTH STATUS AND ACCESS TO ORAL HEALTH CARE IN THE UNITED STATES

Although there is a wide range of diseases and conditions that manifest themselves in or near the oral cavity itself, this report will focus primarily on access to services for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of two diseases and their sequelae: dental caries and periodontal diseases. Dental caries, or tooth decay, is caused by a bacterial infection (most commonly Streptococcus mutans) that is often passed from person to person (e.g., from mother to child). Oral Health in America called dental caries the most common chronic disease of childhood (HHS, 2000b), and it is among the most common diseases in the world (WHO, 2010d). Despite decades of knowledge of how to prevent dental caries, they remain a significant problem for all age groups. Periodontal disease is generally broken into two categories: gingivitis and periodontitis. Gingivitis is an inflammation of the tissue surrounding the teeth that results from a buildup of dental plaque between the tissue and the teeth. It is generally due to poor oral hygiene. Untreated gingivitis can result in periodontitis, the breakdown of the ligament that connects the teeth to the jaw bone, and the destruction of the bone that supports the teeth in the jaw. At least 8.5 percent of adults (ages 20-64) and 17.2 percent of older adults (age 65 and older) in the United States have periodontal disease (NIDCR, 2011a,b).

FIGURE 2-1

Proposed early childhood caries morbidity and mortality pyramid.

SOURCE: Casamassimo et al., 2009. Copyright © 2009 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reproduced by permission.

A Note on Data Sources

The following sections document the oral health status and access to care for various populations. Data was drawn from published studies that rely on a number of data sources, including the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the National Health Interview Survey, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), and smaller-scale surveys. While the magnitude of disparities in oral health and access to care may differ among the various sources, similar conclusions can be drawn from them about disparities in oral health status and access to care. Other researchers have noted similar trends in the past (Macek et al., 2002). Therefore, the committee felt comfortable using a variety of data sources, both national and smaller scale. The committee did not have the ability

to analyze raw data and thus relied on published sources. As a result, the committee did not always use the most recent survey data, because it has not been analyzed in the published literature. In particular, many published studies on oral health status rely on NHANES data from 1988-1994 and 1999-2004, and consequently the committee also relied heavily on those data. While NHANES has included an oral health assessment in subsequent years, the data collected is less detailed and not easily comparable to earlier data. Until 2004, NHANES collected tooth-level data, meaning that a dentist evaluated the teeth of each survey respondent to determine the number of decayed, missing, or filled teeth and surfaces (CDC, 2010b). Beginning in 2005, the oral health survey moved to person-level surveillance for caries, meaning that each survey respondent was evaluated only for the presence or absence of any decayed, missing, and filled teeth (CDC, 2010b; Dye et al., 2011a). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act required the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to return to person-level surveillance for NHANES, although funding has not been appropriated.1

Overall Oral Health Status

In April 2007, the National Center for Health Statistics of the CDC released a comprehensive assessment of the oral health status of the U.S. population (Dye et al., 2007). Using data provided by two iterations of NHANES (NHANES III, 1988-1994, and NHANES, 1999-2004), which is the most comprehensive survey on oral health status in the United States, the assessment concluded that “Americans of all ages continue to experience improvements in their oral health” (Dye et al., 2007). Specifically, the report noted that among older adults, edentulism (complete tooth loss) and periodontitis (gum disease) had declined. Among adults, CDC observed improvements in the prevalence of dental caries, tooth retention, and periodontal health. For adolescents and youth, dental caries decreased, while dental sealants (used to prevent tooth decay) became more prevalent. Encouragingly, the increase in dental sealants was consistent among all racial and ethnic groups, although non-Hispanic black and Mexican American children and adolescents continue to have a lower prevalence of sealants than white children and adolescents, and low-income children receive fewer dental sealants than those who live above 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL).

While the data from the NHANES surveys showed improvements in certain indicators of oral health status across two intervals of time, Americans’ overall health status in the 1999-2004 period remained discouraging.

______________

1Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 148, 111th Cong., 2nd sess. (March 23, 2010), §4102.

For example, over 25 percent of adults 20 to 64 years of age and nearly 20 percent of respondents over age 65 were experiencing untreated dental caries at the time of their examination. Even young children experienced high rates of caries: nearly 28 percent of children ages 2-5 years had caries experience, and 20 percent have untreated caries. Moreover, caries prevalence among preschool children increased between 1988-1994 and 1999-2004 (Dye et al., 2010). In addition, disturbing disparities remain in oral health status for many underserved and vulnerable populations, which will be discussed in detail later in this chapter.

Access to Oral Health Care

Limited and uneven access to oral health care contributes to both poor oral health and disparities in oral health. More than half of the population (56 percent) did not visit a dentist in 2004 (Manski and Brown, 2007), and in 2007, 5.5 percent of the population reported being unable to get or delaying needed dental care, significantly higher than the numbers that reported being unable to get or delaying needed medical care or prescription drugs (Chevarley, 2010). Nearly all measures indicate that vulnerable and underserved populations access oral health care in particularly low numbers. For example, poor children are more likely to report unmet dental need than those with higher incomes (Bloom et al., 2010), non-Hispanic black and Hispanic children and adults are less likely to have seen a dentist in the past 6 months than non-Hispanic white populations (Bloom et al., 2010; Pleis et al., 2010), and less than 20 percent of eligible Medicaid beneficiaries received preventive dental services in 2009 (CMS, 2010). These disparities and others will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Healthy People: Benchmarks for Oral Health

Since 1980, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has used the Healthy People process to set the country’s health-promotion and disease-prevention agenda (Koh, 2010). Healthy People is a set of health objectives for the nation, consisting of (1) overarching goals for improving the overall health of all Americans, and (2) more specific objectives in a variety of focus areas, including oral health. Every 10 years, HHS evaluates the progress that has been made on Healthy People goals, develops new goals, and sets new benchmarks for progress. The goals are developed by relevant HHS agencies, with input from external stakeholders and the public. Healthy People 2020 objectives were released in December 2010 and are listed in Box 2-2.

Healthy People 2010 came to a close with the announcement of the Healthy People 2020 benchmarks in late 2010. Progress on the Healthy

People 2010 goals was mixed, although final data have yet to be analyzed (Koh, 2010; Sondik et al., 2010; Tomar and Reeves, 2009). At the midcourse review in 2006, no oral health objectives had met or exceeded their targets (HHS, 2006). Encouragingly, however, progress was made in a number of categories, including decreasing caries among adolescents (although not among younger children), increasing the proportion of children with dental sealants, increasing the proportion of adults with no permanent tooth loss, and increasing the proportion of the population with access to community water fluoridation (HHS, 2006; Tomar and Reeves, 2009). In contrast, several objectives moved away from their targets. For example, the proportion of children aged 2 to 4 years with dental caries increased from 18 to 22 percent, and the proportion of untreated dental caries in this population increased from 16 to 17 percent (HHS, 2006). In addition, the number of oral and pharyngeal cancers detected at an early stage decreased.

ORAL HEALTH STATUS AND ACCESS TO ORAL HEALTH CARE FOR VULNERABLE AND UNDERSERVED POPULATIONS

While there has been some improvement in the oral health of the U.S. population overall, underserved populations continue to suffer disparities in both their disease burden and access to needed services. For example, dental caries remain a significant problem in certain specific populations such as low-income children and racial and ethnic minorities (Edelstein and Chinn, 2009). According to NHANES, twice as many poor children ages 2 to 11 have at least one untreated decayed tooth, compared to nonpoor children (Dye et al., 2007). In addition, low-income children also receive fewer dental sealants (Dye et al., 2007). Minority children are more likely to have dental decay than white children, and their decay is more severe (IHS, 2002; Vargas and Ronzio, 2006). When migrant and seasonal farmworkers in Michigan were asked which health care service would benefit them the most, the most common response was dental services, ahead of pediatric care, transportation, and interpretation, among other services (Anthony et al., 2008). This section will explore the disparities in status and access to care for a variety of vulnerable and underserved populations.

Children and Adolescents

Children

While not all children are underserved, many children are vulnerable to developing oral diseases, particularly dental caries. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently reported that according to NHANES, dental disease in children has not decreased, noting that about

BOX 2-2

Healthy People 2020: Oral Health Objectives

Oral health of children and adolescents

1. Reduce the proportion of children and adolescents who have dental caries experience in their primary or permanent teeth.

2. Reduce the proportion of children and adolescents with untreated dental decay.

Oral health of adults

3. Reduce the proportion of adults with untreated dental decay.

4. Reduce the proportion of adults who have ever had a permanent tooth extracted because of dental caries or periodontal disease.

5. Reduce the proportion of adults aged 45-74 with moderate or severe periodontitis.

6. Increase the proportion of oral and pharyngeal cancers detected at the earliest stage.

Access to preventive services

7. Increase the proportion of children, adolescents, and adults who used the oral health care system in the past year.

8. Increase the proportion of low-income children and adolescents who received any preventive dental service during the past year.

9. Increase the proportion of school-based health centers with an oral health component.

10. Increase the proportion of local health departments and Federally Qualified Health Centers that have an oral health component.

one in three children aged 2-18 enrolled in Medicaid had untreated tooth decay, and one in nine had untreated decay in three or more teeth (GAO, 2008). The lack of adequate dental treatment may affect children’s speech, nutrition, growth and function, social development, and quality of life (HHS, 2000b). In spite of these significant problems, according to MEPS, only about 25 percent of children under the age of 6, 59 percent of children ages 6-12, and 48 percent of adolescents ages 13-20 had a dental visit in 2004 (Manski and Brown, 2007).

A number of factors are related to the likelihood that a child has visited the dentist in the past year, including insurance status, race, ethnicity, being born outside the United States, language spoken at home, whether the child’s mother has a regular source of dental care (Grembowski et al., 2008; Lewis et al., 2007). Dentally uninsured children receive fewer dental services than insured children (Kenney et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2007;

11. Increase the proportion of patients that receive oral health services at Federally Qualified Health Centers each year.

Oral health interventions

12. Increase the proportion of children and adolescents who have received dental sealants on their molar teeth.

13. Increase the proportion of the U.S. population served by community water systems with optimally fluoridated water.

14. Increase the proportion of adults who receive preventive interventions in dental offices.

Monitoring and surveillance systems

15. Increase the number of states and the District of Columbia that have a system for recording and referring infants and children with cleft lips and cleft palates to craniofacial anomaly rehabilitative teams.

16. Increase the number of states and the District of Columbia that have an oral and craniofacial health surveillance system.

Public health infrastructure

17. Increase the number of health agencies that have a public dental health program directed by a dental professional with public health training.

SOURCE: HHS, 2010.

Manski and Brown, 2007). The data on dental visits for publicly insured children, however, are mixed. Some data indicate that publicly insured children are less likely to receive dental services and receive fewer dental services on average than privately insured children (Manski and Brown, 2007); however, studies that control for race and income (among other factors) indicate that publicly and privately insured children are equally likely to have a preventive dental visit (Kenney et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2007). African American and Latino children are less likely to have had a preventive dental visit (Lewis et al., 2007) or any dental contact in the past year than white children (Bloom et al., 2010). This may contribute to the low levels of dental visits among publicly insured children in uncontrolled estimates, since African American and Latino children are more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009). Children born outside the United States and children whose primary language at home is not English are both less likely than reference groups to have a preventive

dental visit in the past 12 months (Lewis et al., 2007). In addition, lowincome children whose parents regularly visit the dentist are more likely to visit the dentist, according to surveys done in Washington state and Detroit (Grembowski et al., 2008; Sohn et al., 2007).

Adolescents

As noted above, adolescents, generally those aged 10-19 (IOM, 2009), have a high prevalence of oral disease. Risk factors for dental caries are similar to those for other age groups, but adolescents’ risk for oral and perioral injury is exacerbated by behaviors such as the use of alcohol and illicit drugs, driving without a seatbelt, cycling without a helmet, engaging in contact sports without a mouth guard, and using firearms (IOM, 2009). Other concerns among adolescent populations, which are not unique to this age group, include damage caused by the use of all forms of tobacco, erosion of teeth and damage to soft tissues caused by eating disorders, oral manifestations of sexually transmitted infections (e.g., soft tissue lesions) as a result of oral sex, and increased risk of periodontal disease during pregnancy. In an online Harris Interactive poll of nearly 1,200 adolescents, respondents frequently mentioned having access to affordable, convenient, and high-quality dental care as what they would most like to change to make health services more helpful (IOM, 2009).

Homeless Populations

Homeless people have poorer oral health than the general population. However, no national data are available on the oral health status of homeless populations, and the few available studies may skew the results due to sample size, the population surveyed (e.g., people who present at a clinic), and inability to reach the chronically homeless, among other factors. In a national survey, homeless veterans reported higher rates of oral pain, more decayed teeth, and fewer filled teeth than the general population (Gibson et al., 2003). Many homeless veterans reported having oral pain either currently or within the past year (Conte et al., 2006). Similarly, in a small survey of homeless adolescents in Seattle, over 50 percent reported having sensitive teeth, 39 percent reported a toothache, and 27 percent reported sore or bleeding gums (Chi and Milgrom, 2008). In addition, homeless people in these surveys were more likely than the general population to perceive their oral health as poor (Chi and Milgrom, 2008; Gibson et al., 2003). Homeless people also struggle to access oral health care. A national survey of homeless people found that dental care was the most commonly reported unmet health need (Baggett et al., 2010). In fact, homeless people

surveyed at a free dental screening had not seen a dentist in, on average, 5.7 years (Conte et al., 2006).

Homeless populations face a multitude of barriers to both maintaining good oral health and accessing oral health care. They are more likely to engage in behaviors detrimental to oral health such as smoking and using other types of tobacco products (Conte et al., 2006; Gibson et al., 2003), heavy alcohol use (Gibson et al., 2003), and substance abuse (Chi and Milgrom, 2008). They also may lack toothbrushes, toothpaste, clean water, or a place to brush their teeth (Chi and Milgrom, 2008). Homeless people often lack dental coverage, and homeless children struggle to maintain Medicaid coverage because they do not have a permanent address. Over one-third of homeless people at a free dental screening answered that they did not know where to seek dental care if needed (Conte et al., 2006).

Low-Income Populations

Socioeconomic status, as measured by poverty status,2 is a strong determinant of oral health (Vargas et al., 1998). In every age group, persons in the lower-income group are more likely to have had dental caries experience and more than twice as likely to have untreated dental caries in comparison to their higher-income counterparts (Dye et al., 2007). Poor children ages 2-8 have more than twice the rate of dental caries experience as nonpoor children (Dye et al., 2010). Despite the fact that most children living below the FPL are eligible to receive dental care through Medicaid, many children in this income group have untreated decay (Dye et al., 2007). Among adults, tooth extraction is a common treatment for advanced dental decay when financial resources are limited. Consistently, total tooth loss, or edentulism, among persons 65 years of age and over is more frequent among those living below the FPL than among those living at twice the FPL (Dye et al., 2007).

Poor children and adults receive significantly fewer dental services than the population as a whole (Dye et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2007; Stanton and Rutherford, 2003). The likelihood of visiting a dentist decreases with decreasing income (Haley et al., 2008; Manski et al., 2004), and people who live below the FPL are less than half as likely to have visited a dentist in the past year as those who make over 400 percent of the FPL (Manski and Brown, 2007). Children whose families make below 200 percent of the FPL are less than half as likely to have a preventive dental visit than children living in higher-income families (Stanton and Rutherford, 2003).

______________

2 For the purposes of this report, poor refers to individuals and families with income below the FPL; near-poor refers income between 100 and 199 percent of FPL; and nonpoor refers to income above 200 percent of the FPL.

Low-income children also receive fewer dental sealants (Dye et al., 2007), although improvements have been made in this area. Between 1988-1994 and 1999-2004, the largest increase in sealant use was among poor children (an increase of 3 percent to 21 percent) (Dye and Thornton-Evans, 2010). Low-income populations are also more likely to receive episodic or emergency oral health care, rather than receiving preventive care and having a usual source of care (Cohen et al., 2011; Kenney et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2007, 2010).

It is important to note that most children living below the FPL are eligible to receive dental care through Medicaid, and therefore have financing available for oral health care. Indeed, according to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 83 percent of poor children had dental coverage, which is more than any other income group, although they are less likely to have private dental coverage (Manski and Brown, 2007). In contrast, over 60 percent of poor adults lacked dental coverage (Manski and Brown, 2010). Poor populations face a number of barriers to accessing oral health care, many of which will be discussed in greater detail later in this report. They include inability to pay due to lack of dental coverage (Haley et al., 2008; Lewis et al., 2007) or the size of the expense (Haley et al., 2008); difficulty finding a dentist who will accept Medicaid (Lewis et al., 2010); long waits to get appointments (Lewis et al., 2010); lack of transportation (Lewis et al., 2010); higher levels of medical care use (Kuthy et al., 1996); and parents who do not receive regular oral health care (Sohn et al., 2007). Access for low-income populations is also complicated by other factors including age, race, ethnicity, and proximity to oral health providers.

Older Adults

The prevalence of caries and periodontal disease increases steadily with age (Dye et al., 2007). Encouragingly, however, the prevalence of both diseases in older adults has decreased over time (Dye et al., 2007). In addition, the percentage of older adults who are totally edentulous has decreased over time (Lamster, 2004).

Oral health status is related to functional and other health deficiencies. Poor oral health and oral health-related quality of life in older adults are significantly associated with disability and reduction in mobility (Makhija et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011). In addition, older adults are more likely than other segments of the population to have other diseases that may exacerbate their oral health, and vice versa, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and pneumonia (CDC, 2011; El-Solh et al., 2004; NHLBI, 2010).

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has long recognized issues related to the oral health of older adults. For example, in a 1992 study on various needs of older adults, an entire chapter was devoted to oral health, noting

that oral health had improved for older adults, but that adults who retain their teeth continue to be at risk for oral diseases (IOM, 1992). At that time, the IOM recommended to assess the oral health status, risk factors for oral diseases, and use and delivery of oral health services for older adults as well as to consider methods for performing oral cancer screenings in primary care settings.

Older adults frequently do not access oral health care. According to MEPS, only 42 percent of adults age 55 and older reported visiting a dentist in 1996, ranging from 46 percent of 55- to 65-year-olds to 32 percent of adults over age 75 (Manski et al., 2004). Older adults are more likely to have serious medical issues and functional limitations, which can deter them from seeking dental care (Chen et al., 2011; Kiyak and Reichmuth, 2005). Older adults who spend more on medication and medical visits are less likely to use dental services (Kuthy et al., 1996). Additionally, the more functional limitations an older person reports, the less likely he or she is to seek dental care (Dolan et al., 1998). Admittance to long-term care (LTC) facilities creates a significant barrier to receipt of dental care. While federal law requires LTC facilities that receive Medicare or Medicaid funding to provide access to dental care, only 80 percent of facilities report doing so (Jones, 2002). Even when dental care is available, evidence indicates that many residents do not regularly receive dental care and many oral health problems go undetected (Dolan et al., 2005). For example, according to a 1999 survey, only 13 percent of nursing home residents over age 65 received dental services in the billing year of their discharge (Jones, 2002).

Multiple factors contribute to low access to oral health services for older adults. LTC facilities may underestimate the importance of oral health. For example, in a survey of Ohio nursing home executives, 49 percent rated their residents’ oral health as fair or poor but 64 percent were still satisfied with the oral health care provided at their facilities (Pyle et al., 2005). In addition, LTC facilities have difficulty finding dentists to care for their patients. One study showed that the perceived willingness of dentists to treat LTC residents either in the facility or in private offices was the greatest barrier to providing dental care in Michigan alternative LTC facilities (Smith et al., 2010). In the absence of dentists, nursing home staff must identify residents’ oral health needs, but nurses and nursing assistants are not adequately trained to identify many oral health issues (Coleman and Watson, 2006; Jablonski, 2010; Jablonski et al., 2009).

Another significant reason that older adults have difficulty accessing oral health care is the relative lack of training of the health care workforce in the special needs of older adults (Ettinger, 2010). In a 2008 report on the care of older adults (IOM, 2008), the IOM noted that in 1987 the National Institute on Aging predicted a need for 1,500 geriatric dental academicians and 7,500 dental practitioners with training in geriatric dentistry by the

year 2000 (NIA, 1987). By the mid-1990s, however, only about 100 dentists in total had completed advanced training in geriatrics (HRSA, 1995), and little has changed since then. Of the dental students graduating in 2001, almost 20 percent did not feel prepared to care for older adults and 25 percent felt the geriatric dental curriculum was inadequate (Mohammad et al., 2003). The American Dental Association (ADA) currently does not recognize geriatric dentistry as a separate specialty, board certification by the American Board of General Dentistry does not explicitly require questions on geriatric dental care, and none of the 509 residencies recognized by the American Dental Education Association are specifically devoted to the care of geriatric patients (IOM, 2008).

People with Special Health Care Needs

It appears that both children and adults with special health care needs (SHCN)3 have poorer oral health than the general population (Anders and Davis, 2010; Owens et al., 2006). Most, though not all, studies indicate that the overall prevalence of dental caries in people with SHCN is either the same as the general population or slightly lower (Anders and Davis, 2010; López Pérez et al., 2002; Tiller et al., 2001). But available data indicate that people with SHCN suffer disproportionately from periodontal disease and edentulism, have more untreated dental caries, poorer oral hygiene, and receive less care than the general population (Anders and Davis, 2010; Armour et al., 2008; Havercamp et al., 2004; Owens et al., 2006). However, little high-quality data exists on the oral health of people with SHCN. People with SHCN are a difficult population to assess, in part because of their diversity, and also because they are geographically dispersed. Moreover, it is also difficult to analyze national data on this population because their numbers are not large enough to produce reliable statistics. The few available studies of people with SHCN are conducted with populations that are not representative of the SHCN community as a whole (Feldman et al., 1997; Owens et al., 2006; Reid et al., 2003).

Access to care for people with SHCN appears to vary with age. While children with SHCN receive preventive dental care at similar or higher rates than children without SHCN (Kenney et al., 2008; Newacheck and Kim, 2005; Van Cleave and Davis, 2008), adults with SHCN are less likely to have seen a dentist in the past year than people without SHCN (Armour

______________

3 Consensus appears to have developed around a definition for children with special health care needs: “those who have, or are at increased risk for, a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally” (MCHB, 2011). For the purposes of this report, the definition will also be used for adults.

et al., 2008). Despite the similar rates of dental care visits, dental care is the most commonly reported unmet health care need among children with SHCN (Lewis et al., 2005; Newacheck et al., 2000), and children with SHCN are more likely to report experiencing a toothache in the last 6 months than children without SHCN, with more severely affected children more likely to report a toothache (Lewis and Stout, 2010).

Disparities in oral health for people with SHCN are due to a variety of reasons. First, they often take medications that reduce saliva flow, which promotes dental caries and periodontal disease (HHS, 2000b). Additionally, people with SHCN often have impaired dexterity and thus rely on others for oral hygiene (Shaw et al., 1989). They also face systematic barriers to oral health care such as transportation barriers (especially for those with physical disabilities), cost, and health care professionals who are not trained to work with SHCN patients or dental offices that are not physically suited for them (Ettinger, 2010; Glassman and Subar, 2008; Glassman et al., 2005; Stiefel, 2002; Yuen et al., 2010). In addition, the current oral health care system has limited capacity to care for children with SHCN (Ciesla et al., 2011; Kerins et al., 2011). It is likely that children and adults with SHCN experience different barriers to care; however, not enough information exists to divide the populations.

Pregnant Women and Mothers

Oral health problems are common among pregnant women and follow similar disparities with respect to race, ethnicity, income, insurance, and age. However, pregnant women have several unique oral health needs. Pregnant women are susceptible to periodontitis, loose teeth, and pyogenic granulomas, also known as pregnancy oral tumors (Silk et al., 2008; Steinberg et al., 2008). Periodontal disease has been identified in observational studies as a potential factor contributing to adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preterm birth and low birth weight (Albert et al., 2011; Radnai et al., 2006; Vergnes and Sixou, 2007).

The oral health of pregnant women is important not only for their own health, but because there is a strong relationship between the oral health status and oral health care habits of a mother and her children’s oral health status and habits. The bacteria that cause dental caries are transmissible from caregivers, especially mothers, to children (Douglass et al., 2008). Moreover, children of mothers with untreated dental caries and tooth loss are between two and more than three times as likely to have untreated dental caries compared to children whose mothers had no untreated dental caries or no tooth loss (Dye et al., 2011b; Weintraub et al., 2010). Children enrolled in Medicaid are more likely to receive oral health care when their mothers have a regular source of oral health care (Grembowski et

al., 2008). The provision of oral health services for pregnant women and mothers may include education about how their own oral health relates to their children’s oral health as well as how to prevent dental caries in their young children.

Recently, states and health care organizations have promoted the importance and safety of oral health care for pregnant women. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists agree that it is very important for pregnant women to continue usual oral health care (AAP and ACOG, 2007). Both the New York State Department of Health and the California Dental Association have released evidence-based guidelines for treating pregnant women (California Dental Association, 2010; New York State Department of Health, 2006). Both sets of guidelines recommend that prenatal care providers educate women about the importance of oral health and refer them for oral health care, and that oral health care professionals provide routine and necessary oral health care to pregnant women (California Dental Association, 2010; New York State Department of Health, 2006). Recently, several randomized clinical trials of pregnant women with periodontal disease have been performed to examine the effect of receiving treatment during pregnancy or postpartum (Macones et al., 2010; Michalowicz et al., 2006; Offenbacher et al., 2009a). Results of these trials suggest that periodontal treatment is safe for pregnant women and their fetuses and effective in reducing the level of periodontal disease (Michalowicz et al., 2006). However, periodontal treatment during pregnancy does not necessarily reduce the incidence of poor birth outcomes (Macones et al., 2010; Michalowicz et al., 2006; Offenbacher et al., 2009a).

Although oral health care is considered both safe and effective for pregnant women and their fetuses (Michalowicz et al., 2008), many women do not receive dental care during pregnancy (Boggess et al., 2010; Gaffield et al., 2001; Hunter and Yount, 2011; Marchi et al., 2010). Even when women report having an oral health problem during the pregnancy, only about half of them visit a dentist (California Dental Association, 2010; Gaffield et al., 2001; Marchi et al., 2010). Among women with oral health problems, the likelihood of visiting a dentist during the pregnancy is associated with dental coverage status and timing of the first prenatal care visit (Gaffield et al., 2001). Although over 40 percent of all pregnant women have medical insurance through Medicaid (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2007), many of them are not covered for oral health care because only about half of state Medicaid programs pay for the oral health care of pregnant women. In addition, some women report being erroneously informed to not visit the dentist during pregnancy (Boggess et al., 2010).

Racial and Ethnic Minorities

As will be described in more detail below, racial and ethnic minorities experience significant disparities in oral health status and access to oral health care compared to the U.S. population as a whole. These disparities can be attributed to a number of complex societal factors, including lower incomes, a lower prevalence of dental coverage, and a dearth of dentists located in communities where racial and ethnic minorities live, among many other factors.

African Americans

African Americans have poorer oral health than the overall U.S. population throughout the life cycle. African American children and adolescents are have slightly more dental caries and more untreated dental caries than white children and adolescents (Dye et al., 2007). African American adults (ages 20-64) have approximately the same prevalence of dental caries as white adults; however, dental caries in African Americans is much more likely to be untreated (Dye et al., 2007). In addition, African American adults are significantly more likely to have periodontal disease than white adults (Dye et al., 2007). African American older adults have, on average, fewer teeth than whites (Dye et al., 2007). African Americans also perceive their oral health as worse than whites; parents of non-Hispanic black children are twice as likely as parents of white children to rate their child’s oral health as fair or poor (Dietrich et al., 2008); and African American adults are less than half as likely as white adults to rate their oral health as excellent or very good (Dye et al., 2007). Encouragingly, the oral health of African Americans appears to be improving for many, though not all, of these measures. For example, 17 percent of African American adults had periodontal disease in the 1999-2004 NHANES survey, down from 26 percent in the 1988-1994 survey (Dye et al., 2007).

African Americans also experience disparities in access to oral health care. In 2003, 72 percent of African American children received preventive oral health care, compared to 84 percent of white children (Dietrich et al., 2008). In 2009, 53 percent of African American adults reported seeing a dentist or other dental professional in the past year, compared to 61 percent of the overall population (Pleis et al., 2010).

American Indians and Alaskan Natives

American Indians and Alaskan Natives (AI/AN) also have poorer oral health than the overall U.S. population throughout the life cycle. In 1999, the Indian Health Service (IHS) surveyed its patients to determine the bur-

den of dental caries on the AI/AN population and compare AI/AN oral health to the overall populations’ oral health (IHS, 2002). The survey found that AI/AN children and adolescents, ages 2 to 19, are more likely to suffer from dental caries and are more likely to have untreated dental caries as compared to the overall population. The rate of dental caries for AI/AN children ages 2 to 5, for example, is five times the U.S. average, and more than two-thirds of AI/AN children suffer from dental caries (IHS, 2002).

AI/AN adults ages 35 to 44 also have more teeth with untreated dental caries, but fewer missing teeth, and about the same number of filled teeth as the overall population. AI/AN adults over age 55 have fewer teeth, higher rates of dental caries, and more periodontal disease, but fewer root caries than the overall population. AI/AN elders are more likely to be edentulous; two surveys found that at least 40 percent of AI/AN adults between the ages of 65 and 74 were edentulous, compared to 29 percent of the overall population (Jones et al., 2000).

AI/AN populations face complex barriers to attaining good oral health, including a lack of sources of fluoridated water, instability in IHS dental programs, and geographic barriers to care. Historically, IHS has supported water fluoridation on Indian reservations for the prevention of dental caries, but the number of reservation systems submitting fluoridation monitoring reports to IHS dropped from 700 in the early 1990s to fewer than 500 in 1995 (Martin, 2000).

Asian Americans

Although Asian Americans make up a growing proportion of the U.S. population, they have received little attention in the oral health literature. Asian Americans comprise many ethnic subgroups with varying age, education, income, and nativity statuses, and varying abilities to access oral health care (Qiu and Ni, 2003). Underutilization of oral health care among Asian Americans is associated with poverty, lack of dental coverage, and residing in the United States for less than 5 years (Qiu and Ni, 2003).

Latinos

Latinos have poorer oral health and receive fewer dental services as compared to white populations. These disparities exist independently of income level, education, dental coverage status, and attitude toward preventive care (Dietrich et al., 2008). While Latinos are a diverse population, comprising numerous subgroups, more is known about the oral health of Mexican Americans than other subgroups because NHANES oversamples Mexican Americans. Thus, the focus here will be on the oral health status of Mexican Americans, but it should be noted that the expe-

rience of Mexican Americans may not be representative of all Latino subpopulations. Both dental caries experience and untreated dental caries are significantly more prevalent in Mexican American children (ages 2-11) than in both non-Hispanic white and black children (Dye et al., 2007). Mexican American adults have fewer dental caries experiences than white non-Hispanic adults; however, they have higher rates of untreated dental caries (Dye et al., 2007). Disparities in the oral health of Mexican Americans persist throughout the life cycle, in adolescents through older adults (Dye et al., 2007).

Latinos also experience disparities in access to oral health care. They are less likely to report any dental visit in the past year, either for preventive, restorative, or emergency care (Manski and Magder, 1998). Latino children are less likely than white children to have ever seen a dentist or to have seen a dentist in the last year (Dietrich et al., 2008). In 2003, only 67 percent of Latino children received preventive dental care, compared to 84 percent of white children (Dietrich et al., 2008). In 2009, 48 percent of Hispanic and Latino adults reported seeing a dentist or other dental professional in the past year, compared to 61 percent of the adults overall (Pleis et al., 2010).

Acculturation is associated with disparities in Latino oral health,4 indicating that reducing oral health disparities for Latinos requires linguistically and culturally appropriate oral health care and promotion. Latinos who primarily speak Spanish at home are less likely to report a dental visit in the past 12 months than those who speak English (Jaramillo et al., 2009) and are also less likely to have a dental home (Graham et al., 2005). The association between acculturation and oral health disparities persists throughout diverse groups of Latino Americans. Less acculturated Mexican American, Cuban American, and Puerto Rican Americans are all significantly less likely to report receiving recent oral health care than those who are more acculturated (Stewart et al., 2002). Acculturation is likely to be related to access to care rather than overall oral health, because acculturation is associated with missing teeth and untreated decayed surfaces but not with overall experience with dental caries (Cruz et al., 2004).

Rural and Urban Populations

High-quality data on oral health status and access to care by geographic location are sparse. Some data indicate that rural residents have poorer oral health than urban residents (Vargas et al., 2002, 2003b,c), while others indicate that urban residents have more oral health needs (Maserejian et al.,

______________

4 Surveys generally use language as a proxy for acculturation, treating individuals who regularly speak English as more acculturated than those who primarily speak Spanish.

2008). Similarly, some analyses indicate that rural residents access less oral health care or report more problems accessing oral health care than urban residents (NCHS, 2011; Vargas et al., 2003a); however, that association disappears after controlling for supply of dentists (Allison and Manski, 2007). More complex, multivariate analyses are needed to assess whether oral health status and access to care are related to place of residence, or instead to income, education level, supply of dentists, or other predisposing factors.

Rural residents may not access oral health care for a number of reasons. Fewer dentists work in rural areas than urban areas (Doescher et al., 2009; Eberhardt et al., 2001). In addition, a smaller proportion of rural residents have dental coverage, which is a good predictor of receipt of dental care (DeVoe et al., 2003; Lewis et al., 2007). Finally, the water in rural communities is less likely to be fluoridated than city water, which means rural residents are more susceptible to dental caries.

In 2005, the IOM examined the quality of general health care in rural communities (IOM, 2005). The committee specifically noted the role of IHS and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) in providing scholarships and loan repayment for practice in rural areas as well as the efforts of individual programs by dental schools and others in providing exposure to care in rural settings. The committee concluded that “fundamental change in health professions education programs will be needed to produce an adequate supply of properly educated health care professionals for rural and frontier communities.” They recommended that schools (specifically including dental schools) make greater efforts to recruit students from rural areas, to locate a meaningful portion of the formal educational experience in rural settings, to recruit faculty with experience in caring for rural populations, and to develop education programs that are relevant to rural practice.

FACTORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO POOR ORAL HEALTH AND LACK OF ACCESS TO ORAL HEALTH CARE

Underserved and vulnerable populations experience significant barriers to accessing oral health care and improving oral health. Barriers that are unique or particularly significant to a specific population have been discussed, but others cut across demographic lines and affect the oral health of many different populations. Those are discussed here. This list is not intended to be exhaustive, but is intended to highlight areas the committee believes are of importance and where significant progress can be made.

Social Determinants of Oral Health

Social determinants also affect oral health and contribute to inequalities in oral health (Patrick et al., 2006). The World Health Organization

describes social determinants of health as a combination of structural determinants (“the unequal distribution of power, income, goods, and services”) and daily living conditions (“the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age”) (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). Social gradients in dental decay, periodontal disease, oral cancer, and tooth loss have all been reported (Kwan and Petersen, 2010). Income inequality has also been shown to be related to oral health (Bernabé and Marcenes, 2011). Recognizing the relationship between social determinants of health and oral health outcomes is important for developing interventions.

Social determinants of health create significant barriers to reducing and ultimately eliminating disparities in oral health. Progress will require changes in the social and physical environment, such as public education, working and living conditions, health system, and the natural environment (Patrick et al., 2006; Williams, 2005). Interventions will need to focus on the individual, families, and communities (Fisher-Owens et al., 2007). Unfortunately, not enough is known about bridging the science, practice, and policy of social determinants of health so that scientific knowledge can be translated into practical policies that will reduce disparities in oral health (Dankwa-Mullan et al., 2010a,b).

Oral Health Literacy

This section provides a brief overview of oral health literacy. The Committee on an Oral Health Initiative was specifically charged to address oral health literacy, and thus a more complete discussion of oral health literacy can be found in its report Advancing Oral Health in America (see Appendix D). The Committee on Oral Health Access to Services recognizes that oral health literacy is an essential component of access to care, and the brevity of the discussion here is not meant to deemphasize its importance.

Nearly all aspects of oral health care require literacy (e.g., realizing the importance of self-care, understanding that dental caries is an infectious disease, scheduling a dental appointment, completing insurance forms). However, little is known specifically about oral health literacy. The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Workgroup on Oral Health Literacy proposed a research agenda for oral health literacy in 2005 (NIDCR, 2005), but little progress has been made since then.

Available data indicate that the public’s oral health literacy (and general health literacy) is poor (Jones et al., 2007; Kutner et al., 2006). Poor oral health literacy is strongly associated with self-reported lower oral health status, lower dental knowledge, and fewer dental visits. The public has little knowledge about the best ways to prevent oral diseases. Fluoride and dental sealants have long been acknowledged as the most effective ways to

prevent dental caries, yet the public consistently answers that toothbrushing and flossing are more effective (Ahovuo-Saloranta et al., 2008; Gift et al., 1994; Marinho et al., 2003a). Although each year 30,000 Americans are diagnosed with oral cancers and nearly 8,000 people die from them, the public’s knowledge about the risk factors and symptoms of oral cancers is low (ACS, 2009; Cruz et al., 2002; Horowitz et al., 1998, 2002; Patton et al., 2004).

The public’s lack of knowledge about oral health may, in part, be due to low oral health literacy among health care professionals themselves, including both dental and nondental health care professionals. This includes both general health literacy and communication skills (Neuhauser, 2010; Rozier et al., 2011; Schwartzberg et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2002), as well as specific knowledge related to oral health and oral health care (Caspary et al., 2008; Forrest et al., 2000; Quijano et al., 2010; Yellowitz et al., 2000).

Prevention of Oral Diseases and Maintenance of Oral Health

Many oral diseases can be prevented through a combination of steps taken at home, in the dental office or other health care settings, or on a community-wide basis. Increasing access to preventive services is an important component of improving access to oral health care for vulnerable and underserved populations. IOM’s concurrent Committee on an Oral Health Initiative was directly charged to address the role of preventive services in oral health; therefore, a fuller discussion of this topic can be found in its report Advancing Oral Health in America (see Appendix D). So as not to duplicate that committee’s work, this committee chose to provide a brief, broad overview of the prevention of oral diseases.

Fluoride

The oral health benefits of fluoride have been well known for more than 75 years (CDC, 2010a). Fluoride reduces the risk of dental caries in both children and adults (Griffin et al., 2007; IOM, 1997; Marinho, 2009; Marinho et al., 2002, 2003a; NRC, 1989; Twetman, 2009; WHO, 2010c). Fluoride works through a variety of mechanisms, including incorporating into enamel before teeth erupt, inhibiting demineralization and enhancing remineralization of teeth,5 and inhibiting bacterial activity in dental plaque (CDC, 2001; HHS, 2000b).

______________

5 Dental caries work through a process of demineralization: bacteria in the mouth breaks down dietary carbohydrates to form acids, which demineralize the dental enamel and form cavities. Before a tooth becomes fully demineralized and cavitated, it can remineralize if the proper combination of calcium and phosphate (generally from saliva) is present (Featherstone, 2009).

Some modes of fluoride delivery to whole communities involve the addition of very low levels of fluoride to public water systems, salt, or milk. Community water fluoridation is credited with significantly reducing the incidence of dental caries in the United States and is recognized as one of the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century (CDC, 1999a). Evidence continues to reaffirm that community water fluoridation is effective, safe, inexpensive, and is associated with significant cost savings (CDC, 1999b, 2001; Griffin et al., 2001a,b; HHS, 2000b; Horowitz, 1996; Kumar et al., 2010; O’Connell et al., 2005; Parnell et al., 2009; Yeung, 2008). The Task Force on Community Preventive Services recommends community water fluoridation (Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2002), and dental professional associations support water fluoridation (ADA, 2010; ADHA, 2011; APHA, 2008). Over 70 percent of the U.S. population had access to optimally fluoridated water in 2008; Healthy People 2020 set a goal of 79.6 percent by 2020 (HHS, 2010).

Other forms of fluoride are applied personally, by a caretaker, or by an oral health care professional; these include toothpastes, mouth rinses, gels, and varnishes. Fluoride supplements, such as drops and chewable tablets, also may be prescribed or dispensed by oral health care professionals. Fluoride varnish is easily and quickly applied by both dental and nondental health professionals, including medical assistants (commonly during well-child visits) (Grossman, 2010). It has been shown to be effective in the prevention of dental caries in both deciduous and permanent teeth (Autio-Gold and Courts, 2001; Beltran-Aguilar et al., 2000; Marinho et al., 2002). The interval for frequency of application of fluoride varnish varies depending on the risk of the patient (ADA, 2006).

Dental Sealants

Dental sealants (“sealants”) prevent dental caries from developing in the pits and fissures of teeth,6 where dental caries is most prevalent (Ahovuo-Saloranta et al., 2008). A Cochrane review of sealant studies found that resin-based sealants were effective at preventing dental caries, ranging from an 87 percent reduction in dental caries after 12 months to 60 percent at 48-54 months (Ahovuo-Saloranta et al., 2008). Sealants can also be placed over noncavitated carious lesions to slow the progression of the lesions (Griffin et al., 2008).

Despite their effectiveness, few children have sealants. The most recent NHANES (1999-2004) data indicate that 32 percent of 8-year-olds and 21 percent of 14-year-olds have sealants on their permanent molars (Dye et al.,

______________

6 A dental sealant is a thin, protective coating of plastic resin or glass ionomer that is applied to the biting surfaces of teeth to prevent food particles and bacteria from collecting in the normal pits and fissures and developing into caries.

2007). This is a significant increase from 1988-1994, when 23 percent of 8-year-olds and 15 percent of 14-year-olds had sealants, but it falls short of the Healthy People 2010 goal of 50 percent for both groups (Dye et al., 2007; HHS, 2000a). In addition, low-income children, who are most likely to have dental caries, are the least likely to receive sealants (Dye et al., 2007).

Sealants can be applied in a dental office or in community-based programs, such as school-based sealant programs. Many sealant programs target high-risk populations, which have proven to be effective for the prevention of dental caries as well as demonstrate cost savings (Kitchens, 2005; Pew Center on the States, 2010; Weintraub, 1989, 2001; Weintraub et al., 1993, 2001). The Task Force on Community Preventive Services recommends school-based sealant programs, although evidence is insufficient to comment on the effectiveness of similar state- or community-wide programs (Truman et al., 2002). School-based sealant programs are discussed further in Chapter 4.

Oral Health and Personal Health Behaviors

While community and dental-office based interventions are important for preventing oral diseases, personal behaviors also play an important role. A healthy diet is important for maintaining oral health. Dietary carbohydrates, sugar-rich foods and drinks, and carbonated beverages all are implicated in the formation of dental caries (Burt et al., 1988; Ehlen et al., 2008; Grindefjord et al., 1996; Heller et al., 2001; HHS, 2000b; Kitchens and Owens, 2007; Moynihan and Petersen, 2004; Sundin et al., 1992; WHO, 2010a). Fruits and vegetable consumption, however, can protect against oral cancer (HHS, 2000b; Pavia et al., 2006; WHO, 2010a). In addition, an insufficient level of folic acid is a risk factor in the development of birth defects such as cleft lip and palate (HHS, 2000b).

Both tobacco use and excessive alcohol consumption are risk factors for oral cancers, and when used together they act synergistically as carcinogens (HHS, 2000b; WHO, 2010a). Together, tobacco use and excessive alcohol consumption account for 90 percent of all oral cancers (Truman et al., 2002). In addition, tobacco use is associated with the development and progression of periodontal disease, oral candidiasis in HIV-positive individuals, oral cancer recurrence, and congenital birth defects such as cleft lip and palate (Burns, 1996; Conley et al., 1996; Gelskey, 1999; HHS, 2000b; Palacio et al., 1997; WHO, 2010b; Wyszynski et al., 1997).

Personal hygiene includes toothbrushing, flossing, and the use of mouth rinses. Regular toothbrushing with fluoridated toothpaste reduces caries risk for both dental caries and gingival inflammation (Deery et al., 2004; Marinho, 2009; Marinho et al., 2003a,b; Robinson et al., 2005; Walsh

et al., 2010). However, the relationship between self-care, supragingival plaque, and periodontal disease development and disease prognosis is weak (Lindhe et al., 1989).

Disease Management

While the committee prioritizes prevention in its vision, it recognizes that many individuals have existing diseases that must be treated. Traditionally, dental treatment has focused on surgical interventions and standardized patient education. But recently some oral health educators and practitioners have adopted personalized chronic disease and risk assessment models for oral health diseases, particularly dental caries (Edelstein, 2010; Featherstone et al., 2003; Fontana and Zero, 2007; Lindskog et al., 2010; Yorty et al., 2011). Although caries has often been considered an infectious disease, it has many features of a chronic disease that make it a promising candidate for management through risk assessment, including a complex etiology, long duration, unresponsiveness to acute management, and progressive destruction (Edelstein, 2010). A full discussion is beyond the scope of this report, but this section will provide a brief introduction to caries chronic disease and risk management models.

Caries risk-management models recognize that patients have different risks for developing caries and thus should be treated differently. Riskassessment tools instruct the provider to assess the patient’s caries history, bacteria levels, diet, saliva flow, and access to fluoridated water, among many other factors, and base the treatment on the patient’s risk factors (Featherstone et al., 2007; Jenson et al., 2007; Ramos-Gomez et al., 2007). For example, a patient with a low bacteria count, a history of few caries, and who regularly drinks fluoridated water and brushes with fluoridated toothpaste should receive different interventions than a patient with a high bacteria count, many previous caries, and less access to fluoride. The first patient may not need as many dental visits or as many professional fluoride applications, while the second patient may need more tailored health education and more frequent dental visits and services (Featherstone et al., 2007; Jenson et al., 2007; Ramos-Gomez et al., 2007). In the risk-assessment model, patients may be advised to deviate from the standard semi-annual dental recall visit; patients with higher risk may need to see an oral health provider more frequently, while patients with low risk may only need to visit the dentist yearly (Patel et al., 2010). Early evidence indicates that risk-management models are successful at reducing cariogenic bacteria and future caries compared to conventional care (Featherstone and Gansky, 2005).

Quality Assessment

Despite the current interest in the quality of general health care, little is known about the quality of oral health care. While significant efforts are being made in medicine to develop quality measures, understanding about measurement and assessment of the quality of oral health care lags far behind (Stanton and Rutherford, 2003). A review of current National Quality Forum-endorsed measures of quality finds no measures related to oral health (National Quality Forum, 2010). Further, the annual AHRQ National Healthcare Quality Report and the National Healthcare Disparities Report currently include only information about access to dental services and not about the state of quality in oral health care (AHRQ, 2010). This is not to say that oral health quality measures do not exist, but that they lag far behind quality measures in other health care fields. None of the existing quality measures in oral health care assess long-term patient outcomes; they are limited to measures of technical excellence, patient satisfaction (as opposed to patient experience), service use, and structure and process measures (Bader, 2009a). However, the ADA has recently convened a group of stakeholders, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, in a Dental Quality Alliance, which is charged with developing pediatric oral health quality measures (Rich, 2010).

Two significant barriers prevent the further development of quality measures in oral health: a dearth of evidence-based standards and guidelines, and the lack of universally accepted and used diagnosis codes in dentistry. The development of new measures depends on evidence-based standards and guidelines from which to create metrics. Quality measurement in dentistry is hampered by the absence of a strong evidence base for most dental treatments and, therefore, a lack of evidence-based guidelines (Bader, 2009b; Crall et al., 1999). In fact, many Cochrane reviews in dentistry did not have enough evidence to answer the research question posed (Ashley et al., 2009; Bader, 2009a,b; Bonner et al., 2006; Esposito et al., 2007; Fedorowicz et al., 2009; Hiiri et al., 2010; Rickard et al., 2004; Yeung et al., 2005). Dental research is challenged in part because with the typical small practice design, it can be difficult to collect outcomes data due to the need to gather data from multiple practices as well as integrate the variety of forms that are used to collect the same data (Bader, 2009a). The practice design also makes it difficult to disseminate evidence when it exists; most dentists work alone, so information sharing is limited, and few have chairside access to journals or computers (Bader, 2009b).

The absence of a universally accepted set of diagnosis codes among dentists also is a barrier to developing quality measures (Bader, 2009a; Crall et al., 1999; Garcia et al., 2010). Several code sets are available for oral health, but they have not been put into general use (Kalenderian et al.,

2011; Leake, 2002). The ADA has developed a comprehensive system of diagnostic codes, the Systematized Nomenclature of Dentistry (SNODENT), but it is yet to be released. Several closed-panel delivery systems have also developed oral health code sets for use inside their systems, but they are not available to the general public (Bader, 2009a). Ideally, the diagnostic codes used by dentists would be compatible with codes used by other health care professionals, so that consistent oral health information could be collected from all types of providers. In addition, oral health quality measures need to be developed in the context of available data sources. Finally, in addition to the barriers discussed here, many other factors beyond the scope of this report will contribute to the complexity of developing better quality measures for oral health. They include the privacy and confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (and electronic health record standards, among others).

The committee noted the following key findings and conclusions:

• Oral health is inextricably linked to overall health.

• The overall oral health status of the U.S. population has improved; however, significant disparities exist for vulnerable populations, including people with low incomes, racial and ethnic minorities, children, rural populations, pregnant women, older adults, people with special health care needs, and homeless people.

• Many populations with poor oral health are underserved by the current oral health system.

• Many complex and interrelated factors contribute to poor oral health and lack of access to oral health care, including social determinants of health, poor health literacy, a lack of emphasis on preventive oral health interventions, and a lack of quality measures by which to evaluate and improve oral health care.

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics) and ACOG (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology). 2007. Guidelines for perinatal care. 6th ed. Elk Grove, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

ACS (American Cancer Society). 2009. Cancer facts and figures 2009. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

ADA (American Dental Association). 2006. Professionally applied topical fluoride: Evidence-based clinical recommendations. Journal of the American Dental Association 137(8):1151-1159.

ADA. 2010. Fluoride & fluoridation. http://www.ada.org/2467.aspx (accessed September 16, 2010).

ADHA (American Dental Hygienists Association). 2011. Public health. http://www.adha.org/publichealth/index.html (accessed March 17, 2011).

Ahovuo-Saloranta, A., A. Hiiri, A. Nordblad, H. Worthington, and M. Mäkelä. 2008. Pit and fissure sealants for preventing dental decay in the permanent teeth of children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4):CD001830.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2010. National healthcare quality & disparities reports: NHQRDRnet. http://nhqrnet.ahrq.gov/nhqrdr/jsp/nhqrdr.jsp (accessed November 29, 2010).

Albert, D. A., M. D. Begg, H. F. Andrews, S. Z. Williams, A. Ward, M. Lee Conicella, V. Rauh, J. L. Thomson, and P. N. Papapanou. 2011. An examination of periodontal treatment, dental care, and pregnancy outcomes in an insured population in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 101(1):151-156.

Al-Hashimi, I. 2001. The management of SjÖgren’s syndrome in dental practice. Journal of the American Dental Association 132(10):1409-1417.

Allison, R. A., and R. J. Manski. 2007. The supply of dentists and access to care in rural Kansas. Journal of Rural Health 23(3):198-206.

Anders, P. L., and E. L. Davis. 2010. Oral health of patients with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Special Care in Dentistry 30(3):110-117.

Anthony, M., J. M. Williams, and A. M. Avery. 2008. Health needs of migrant and seasonal farmworkers. Journal of Community Health Nursing 25(3):153-160.

APHA (American Public Health Association). 2008. Community water fluoridation in the United States. http://www.apha.org/advocacy/policy/policysearch/default.htm?id=1373 (accessed September 28, 2010).

Armour, B. S., M. Swanson, H. B. Waldman, and S. P. Perlman. 2008. A profile of state-level differences in the oral health of people with and without disabilities, in the U.S., in 2004. Public Health Reports 123(1):67-75.

Ashley, P. F., C. E. C. S. Williams, D. R. Moles, and J. Parry. 2009. Sedation versus general anaesthesia for provision of dental treatment in under 18 year olds. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1):CD006334.

Autio-Gold, J. T., and F. Courts. 2001. Assessing the effect of fluoride varnish on early enamel carious lesions in the primary dentition. Journal of the American Dental Association 132(9):1247-1253.

Bader, J. D. 2009a. Challenges in quality assessment of dental care. Journal of the American Dental Association 140(12):1456-1464.

Bader, J. D. 2009b. Stumbling into the age of evidence. Dental Clinics of North America 53(1):15-22.

Baggett, T. P., J. J. O’Connell, D. E. Singer, and N. A. Rigotti. 2010. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. American Journal of Public Health 100(7):1326-1333.

Beltran-Aguilar, E. D., J. W. Goldstein, and S. A. Lockwood. 2000. Fluoride varnishes: A review of their clinical use, cariostatic mechanism, efficacy and safety. Journal of the American Dental Association 131(5):589-596.

Bernabé, E., and W. Marcenes. 2011. Income inequality and tooth loss in the United States. Journal of Dental Research. Published electronically April 20, 2011. doi: 10.1177/0022034511400081.

Blaizot, A., J. N. Vergnes, S. Nuwwareh, J. Amar, and M. Sixou. 2009. Periodontal diseases and cardiovascular events: Meta-analysis of observational studies. International Dental Journal 59(4):197-209.

Bloom, B., R. A. Cohen, and G. Freeman. 2010. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Hyattsville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services.

Boggess, K. A., D. M. Urlaub, K. E. Massey, M.-K. Moos, M. B. Matheson, and C. Lorenz. 2010. Oral hygiene practices and dental service utilization among pregnant women. Journal of the American Dental Association 141(5):553-561.

Bonner, B., J. Clarkson, L. Dobbyn, and S. Khanna. 2006. Slow-release fluoride devices for the control of dental decay. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4):CD005101.

Burns, D. N., D. Hillman, J. D. Neaton, R. Sherer, T. Mitchell, L. Capps, W. G. Vallier, M. D. Thurnherr, and F. M. Gordin. 1996. Cigarette smoking, bacterial pneumonia, and other clinical outcomes in HIV-1 infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology 13(4):374-383.

Burt, B. A., S. A. Eklund, K. J. Morgan, F. E. Larkin, K. E. Guire, L. O. Brown, and J. A. Weintraub. 1988. The effects of sugars intake and frequency of ingestion on dental caries increment in a three-year longitudinal study. Journal of Dental Research 67(11):1422-1429.

California Dental Association. 2010. Oral health during pregnancy and early childhood: Evidence-based guidelines for health professionals. Sacramento, CA: California Dental Association.

Casamassimo, P. S., S. Thikkurissy, B. L. Edelstein, and E. Maiorini. 2009. Beyond the DMFT: The human and economic cost of early childhood caries. Journal of the American Dental Association 140(6):650-657.

Caspary, G., D. M. Krol, S. Boulter, M. A. Keels, and G. Romano-Clarke. 2008. Perceptions of oral health training and attitudes toward performing oral health screenings among graduating pediatric residents. Pediatrics 122(2):e465-e471.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1999a. Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900-1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 48(12):241-243.

CDC. 1999b. Water fluoridation and costs of medicaid treatment for dental decay—Louisiana, 1995-1996. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 48(34):753-757.

CDC. 2001. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 50(RR14):1-42.

CDC. 2010a. CDC honors 65 years of community water fluoridation. http://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/65_years.htm (accessed September 16, 2010).

CDC. 2010b. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 1999-2010 survey content. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

CDC. 2011. National diabetes fact sheet, 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/factsheet11.htm (accessed May 2, 2011).

Chávarry, N., M. V. Vettore, C. Sansone, and A. Sheiham. 2009. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and destructive periodontal disease: A meta-analysis. Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry 7(2):107-127.

Chen, H., J. Moeller, and R. J. Manski. 2011. The influence of comorbidity and other health measures on dental and medical care use among Medicare beneficiaries 2002. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. Published electronically May 11, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00251.x.

Chevarley, F. M. 2010. Percentage of persons unable to get or delayed in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines: United States, 2007. Statistical brief #282. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Chi, D., and P. Milgrom. 2008. The oral health of homeless adolescents and young adults and determinants of oral health: Preliminary findings. Special Care in Dentistry 28(6):237-242.

Ciesla, D., C. A. Kerins, N. S. Seale, and P. S. Casamassimo. 2011. Characteristics of dental clinics in U.S. children’s hospitals. Pediatric Dentistry 33(2):100-106.

CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). 2010. Annual EPSDT participation report form CMS-416, fiscal year 2009. https://www.cms.gov/MedicaidEarlyPeriodicScrn/Downloads/2009National.pdf (accessed March 15, 2011).

Cohen, L. A., A. J. Bonito, C. Eicheldinger, R. J. Manski, M. D. Macek, R. R. Edwards, and N. Khanna. 2011. Comparison of patient visits to emergency departments, physician offices, and dental offices for dental problems and injuries. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 71(1):13-22.

Coleman, P., and N. M. Watson. 2006. Oral care provided by certified nursing assistants in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 54(1):138-143.