4

The State of Prevention

Research in Low- and

Middle-Income Countries

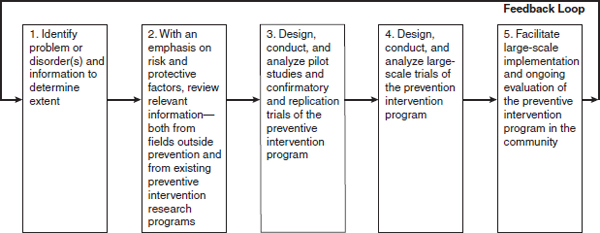

The state of research on prevention of violence against women and children was a central theme of the workshop. A number of speakers referred to advances in knowledge and practices while also pointing to various gaps in knowledge—particularly in low- and middle-income countries—as well as to challenges in the prevention research cycle. Figure 4-1, which is taken from an Institute of Medicine (IOM) report published in 1994, illustrates the five steps in the prevention intervention research cycle. As noted in the report (IOM, 1994), while the feedback loop is shown as connecting box 5 with box 1, in reality there should be a nearly continuous feedback loop between researchers and practitioners at all stages of the prevention research process. The illustration is provided in order to facilitate consistency throughout this section and should not be construed as a product of this workshop.

Discussion at the workshop focused mainly on data collection, translation, implementation, and dissemination efforts related to violence prevention. This summary will refer to the activities listed in boxes 1 and 2 of Figure 4-1 as data collection. This includes data on the prevalence and incidence of violence perpetration and victimization as well as similar information related to risk and protective factors. The term translation will be used to refer to the process by which research knowledge that is related to violence prevention either directly or indirectly is used to inform violence prevention activities and initiatives. This process is represented by the arrow connecting boxes 2 and 3. The term implementation refers to a specific set of activities that are designed to put an intervention into practice. This term will generally be used to refer to activities that have been described

FIGURE 4-1 Preventive intervention research cycle.

SOURCE: IOM, 1994.

in sufficient detail that the intervention can be replicated as necessary, and it is represented by the arrow that connects boxes 3 and 4. The term dissemination refers to a set of activities that is intended to expand the usage of an intervention and is represented by box 5. The phrase “scaling up” was used frequently by workshop participants and is interpreted within this summary to refer to dissemination activities.

DATA FROM LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

The use of data was an important theme of the workshop, and a number of participants commented on the dearth of data available from low- and middle-income countries. Workshop speaker Claudia García-Moreno noted that the majority of the evidence base related to violence against women and children comes from high-income countries. Another workshop speaker, James Lang from the United Nations Development Programme, commented that the currently available data have a number of problems related to the methodologies and measurements used and the lack of longitudinal data. Workshop participants mentioned a number of implications that the limitations in data from low- and middle-income countries have for successful prevention of violence against women and children. These implications will be discussed later in this section.

Although workshop participants lamented the lack of data from low- and middle-income countries, many speakers also noted that significant progress has been made over the past decade. In particular, speakers mentioned a number of studies that have taken place in low- and middle-income countries in recent years as examples of high-quality studies with a focus on violence prevention, some of which were coordinated by the speakers and participants at the workshop. Three studies that were frequently cited

when discussing the incidence and prevalence data related to violence against women and children were the World Health Organization’s Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women (García-Moreno et al., 2005), which was coordinated by workshop speaker Claudia García-Moreno; the World Health Organization’s World Report on Violence and Health (Krug et al., 2002); and the International Men and Gender Equality Survey IMAGES), conducted jointly by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and Instituto Promundo and coordinated by workshop speaker Gary Barker (Barker et al., 2011).

A number of other high-quality studies in low- and middle-income countries were mentioned during the workshop. In addition to the IMAGES study, Dr. Ellsberg cited another ICRW study, Intimate Partner Violence: High Costs to Households and Communities, which provides data from Bangladesh, Morocco, and Uganda (Duvvury, 2009). She also noted that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has produced reports on reproductive health in a number of low- and middle-income countries that have included data about violence against women and children. Dr. García-Moreno specifically cited one of the CDC studies that examines the health consequences of sexual violence against girls in Swaziland (Reza et al., 2009). Dr. Ellsberg also pointed to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) conducted by Macro International as an important source of data related to the prevalence and consequences of different forms of violence against women and children in low- and middle-income countries.

TRANSLATION

Another important step in the prevention research cycle that was discussed during the workshop is translation, which is the process of taking research findings and making that information relevant to programs and policies. This process is represented in Figure 4-1 as the arrow connecting the first two boxes, which correspond to important data collection activities, to box 3 which represents intervention development. Monique Widyono, from the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), noted that translation is more effective when one understands what information will be helpful for program and policy leaders before collecting the data. In a similar vein, workshop participant and forum member Jim Mercy discussed Together for Girls, a collaborative initiative of United Nations agencies, the U.S. government, and the private sector aimed at addressing sexual violence among girls. He noted that one of the three main pillars of the program is to collect data that quantify and describe the problem of sexual violence against girls and that can then guide action, while also working with countries in translating that information to policies and prevention programs. Judy Langford of the Center for Study of Social

Policy described the practical implications of translation research, stating that facilitating high-quality programs that are based in research requires researchers to do a better job of distilling the data to discover “the kernel of truth” that is most central to the model that will be used to develop programs and policies.

IMPLEMENTATION

Several workshop speakers discussed the importance of implementation research and the implications that high-quality implementation efforts have for the effectiveness of programs and policies that are based on scientifically sound evidence. Workshop participant and forum chair Mark Rosenberg said, “As we are trying to develop interventions that can travel well and can be put in place in developing countries that don’t have big budgets, it will become more and more important for us to move into this next stage of research, looking at implementation and delivery.” As noted above, in this report implementation refers to a specific set of activities that are designed to put an intervention into practice and is represented in Figure 4-1 by the arrow connecting boxes 3 and 4. Some participants spoke about different aspects of implementation, while others gave specific examples based on their experiences with particular programs and initiatives.

Dr. García-Moreno framed the issue of interventions targeting violence against women and children with the statement, “We know that services for victims work.” That point was emphasized by several workshop participants who stressed that there are many very good programs that are effective in reducing violence against women and children and in mitigating the negative health consequences that result from exposure to violence.

One of the most common themes related to implementation was the need to ensure that programs are implemented in a way that is appropriate for the particular communities that are being targeted. This issue is particularly salient for efforts in low- and middle-income countries given that, until very recently, most research on the prevention of violence against women and children has been conducted in high-income countries such as the United States. As Dr. Crooks commented, “When we talk about taking programs to other communities or even other cultures and countries, we can’t assume that [just because] a program has really strong evidence in one setting [that it] is going to travel well.” Workshop speaker Rachel Jewkes also commented that although a critical component of a program may be relevant in many different settings, the best way to achieve that component may differ from culture to culture. For example, she noted that although an intervention may call for building social participation, the best way to build social participation in a rural village in South Africa is likely to be different from the best approach in an urban area. This fact that cultures

can vary both within countries and across countries was mentioned by a number of workshop participants.

Several workshop participants and speakers described issues that are important to consider when implementing an intervention originally developed in a different setting or cultural context. Dr. Amaro said that there is very little scientific evidence that speaks to how to adapt interventions to different cultures, and various participants cautioned against thinking that simply translating the language in which the intervention is carried out should be sufficient when adapting interventions to other settings. For example, Dr. Ford noted during his presentation that the Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Treatment (TARGET) curriculum was translated both in terms of language and in terms of culture in order to be relevant to the communities for which it was being adapted. Dr. Crooks echoed this point, noting that often “the manual gets changed in terms of the pictures in it, or people throw in a few cultural teachings or stories and think that is it, and it is essentially the same model.” She also commented that people developing implementation efforts need to be open to identifying totally different approaches that build on culturally relevant protective factors in order to achieve the same ultimate outcomes. Discussing ways to address this challenge, workshop participant and forum member Michael Phillips said that there is a need for a more formalized approach to implementation that uses situation analysis to examine the various aspects of a setting that will help identify how best to adapt a particular intervention.

A number of workshop speakers shared examples that illustrated the importance of considering cultural values when implementing interventions, particularly interventions that are being adapted for different populations. Dr. Wilson offered an example of the consequences of failing to make sure that an intervention is culturally relevant. An initiative in New Zealand to address sudden infant death syndrome among the Māori communities was initially unsuccessful, she said, because the initiative had not incorporated Māori values. When the initiative was modified to take these values into account, it was much more successful. Dr. Tiwari also provided an example of cultural adaptation in her presentation. Describing two interventions that were implemented in Hong Kong, she explained how she and her colleagues were able to take an assessment tool that was in use in the United States and not only translate it but also take the time to validate the Chinese version. She also described developing a parenting program for expecting couples that addressed couple communication in the context of infant care education, taking into account the fact that a therapeutic label could be off-putting to Chinese couples while a focus on education was more in line with their cultural values. Finally, she noted that incorporation of Chinese health concepts and traditional stories was important because most of the couples were living in a dual world. “Many of them are very Westernized,”

she said, “but at the same time they have to cope with the Chinese traditional beliefs that are passed down by their parents.”

In addition to Dr. Phillips’ comments about the use of situation analysis as a tool to characterize communities more systematically in order to develop more effective adaptations of interventions, a number of participants and speakers spoke of the importance of engaging with community members. Dr. Jewkes said, “The best way of making sure you don’t make mistakes over this is by using participatory methods.” Dr. Barker discussed two initiatives in India and Brazil aimed at engaging men in efforts to reduce violence against women and children. He noted that participants in both countries helped to develop a symbol that could identify them as men who were questioning the use of violence against women and children. Dr. Barker also noted that most of the activities used to raise public awareness within their respective communities were developed by the group members, which made it more likely that they would be relevant and reach their intended audiences. Other examples of engaging with community members and leaders came from North America and New Zealand. During Dr. Wolfe’s presentation on the Fourth R (see Chapter 8 for more detailed information on the program), he noted that schools and communities in North America are asked to involve their youth and some of their local teachers in modifying program implementation for their own communities. Dr. Wilson described how focus groups in New Zealand with Māori mental health nurses were important in efforts to make sure an intervention designed to provide women with resources related to intimate partner violence was appropriate for the target population.

In addition to discussing these various cultural concerns, workshop participants also noted that understanding the specific mechanisms that are most effective in a given intervention is crucial in guiding the implementation of previously researched interventions in new settings. Dr. Amaro said that there is a need for more research on the efficacy of interventions, including more controlled studies, in order to understand the important mediators and key program components. Dr. Edleson challenged participants to consider how to transport and diffuse evidence-based interventions without losing the strength of the original models. One particular example of this challenge was mentioned by a number of workshop participants: the nurse home visiting program developed by Dr. David Olds. Dr. Crooks said, “The original nurse visitation program developed by Olds has not necessarily replicated well or traveled or adapted as well. When this same program has been done using paraprofessionals, the outcomes have been more disappointing.” Discussing replication challenges, Ms. Langford suggested that the Strengthening Families framework has been broadly successful because it provides a very simple research-based framework that is easy to apply across many settings. She remarked that the “most interesting part to me

has been the way that parents, parent leaders, have taken the protective factors framework and begun to create strategies to have conversations among themselves.”

Bryan Samuels spoke of the need to evaluate program implementation efforts that involve modification to the original design. Much of the implementation research leaves one “with an understanding of whether a program worked or didn’t work, and the impact that it had.” However, he added, “What you don’t come away with is an understanding of whether certain components of the program had a greater impact or not versus aspects of the program that didn’t.” Mr. Samuels also said that in moving forward there is a need to identify the relevant components of an intervention in order to know which components are most important to evaluate when implementing an evidence-based intervention. To that end, a workshop attendee noted that organizations often identify manualized interventions and then implement them without a plan to evaluate their efforts. He noted that opportunities exist for local evaluations that seek to marry quality research with quality program implementation. There are “not enough people coming in [to the National Institute of Drug Abuse] with applications for implementation and dissemination research, but they are high priorities for us,” he said.

Another theme that arose during the workshop was the idea that in order for interventions to be implemented well, it will be important to establish the necessary public health infrastructure and workforce and also to better understand the impact of program implementation on those who are actually implementing the programs. Dr. Wyatt noted that an important part of implementation research is studying the impact of an intervention on the organizations that are implementing the interventions, including efforts to understand the effects on the staffs of those organizations. She also suggested that it is important for people to recognize that interventions can create a particular burden for a community and that costs of such interventions need to be more closely examined and better understood.

DISSEMINATION

The goal of developing a violence prevention workforce points directly to the final stage in the prevention research cycle. Dissemination refers to a set of activities intended to expand the usage of an intervention. As described by workshop speaker Monique Widyono, dissemination is “really about galvanizing action and momentum around work that is already happening on the ground and being able to share that [work].” Many of the concerns that were discussed in the section on implementation were also raised during conversations about dissemination, particularly concerns related to culturally relevant adaptations and the need to continually monitor

and evaluate an implementation. Indeed, implementation and dissemination can share many of the same activities conceptualized in the framework shown in Figure 4-1. Thus this section focuses primarily on the workshop’s discussions about efforts to share information across settings and to scale up interventions.

Workshop participants discussed a number of initiatives that focus on dissemination activities as a part of their mission. In particular, workshop speaker Cheryl Thomas of Advocates for Human Rights noted that UN Women recently launched its Global Virtual Knowledge Centre to End Violence Against Women and Girls (UN Women, 2011). This initiative is intended to “encourage and support the efficient and effective design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of evidence-based programming, to prevent and respond to violence against females.” Ms. Thomas encouraged individuals to review the databases on the website in order to contribute to the centralized knowledge base that is being developed.

The InterCambios Alliance, described by Monique Widyono on behalf of Margarita Quintanilla, offers an example of efforts to engage in implementation and dissemination activities on a regional scale. Ms. Widyono noted that the alliance’s work is not focused on the development of new materials but rather on sharing and adapting materials that have already been developed and have shown promise. The alliance also identifies programs that have already been evaluated in other settings, introduces them to the communities in which the members of the InterCambios Alliance work, tests them, and asks local organizations if the program seems like a good fit for their community. The final step in the process, Ms. Widyono said, is to engage in efforts to disseminate those programs widely. InterCambios’ efforts to test and adapt programs that have already been proven to be successful in other settings illustrate what many workshop participants had noted about the importance of thoughtful dissemination. Workshop participants talked about various efforts to create centralized repositories of information related to successful violence prevention interventions and also spent time discussing the aspects of dissemination that deal with scaling up interventions so that they can be implemented on a larger scale. The importance of ensuring that interventions brought into new communities and new settings are adapted to meet the specific needs and values of the populations being targeted was a common theme in discussions of scaling up. A number of participants mentioned flexibility as an important characteristic of those interventions or models that can be successfully brought to large-scale implementation. Ms. Langford said that an important aspect of efforts to disseminate the Strengthening Families framework was to incorporate lessons from early adopters of the model and the adaptations that they found to be successful, while maintaining a focus on fidelity to the core components of the model. Similarly, Dr. McCaw noted that in scaling up the Family Domestic Violence Program among Kaiser

Permanente facilities in Northern California from 1 pilot facility to an eventual total of 46 facilities, she learned that it is important for the model to be “easy to understand and easy to customize.”

Another theme that emerged from comments on how to facilitate successful large-scale implementation was the need to provide some specific guidance related to the implementation of a particular intervention. Dr. McCaw said that developing a set of tools helps to facilitate implementation in new sites and that it was important in her efforts to increase the number of Kaiser Permanente facilities offering the Family Domestic Violence Program. Similarly, Ms. Widyono noted that an important part of the work done by the InterCambios Alliance is to provide a set of curricula or tools to individuals and organizations that are seeking to adopt an intervention. Another example of how program developers can provide tools to facilitate large-scale implementation while also maintaining flexibility was provided by Dr. Wolfe’s remarks about encouraging schools to adapt the Fourth R curriculum to meet the needs and values of their communities, including allowing parochial schools to emphasize abstinence.

Various workshop participants mentioned workforce and infrastructure development as ways that countries can further advance violence prevention efforts and, in particular, scale up proven interventions. Mr. Samuels said that, from his perspective as a policy maker, it is important to create “a supportive system that brings with it a set of generic skills that then allow training to augment the particulars of a program.” Dr. Mercy suggested that additional efforts should be made to develop a “cadre of people who can understand the evidence base and can work at the ground and community level to work with people who are going to integrate these types of effective programs into their schools, their service programs or whatever.” To that end, workshop participant Rosemary Chalk from the Institute of Medicine drew a parallel between the current need to adapt and implement evidence-based violence prevention interventions in communities and similar efforts a century ago to implement research-based agriculture techniques through the creation of the Agricultural Extension Service. Dr. Chalk remarked that it might be helpful to think about how people can work in local communities and build on local practices while at the same time not having to develop completely new programs for each community. Rather, she suggested there might be some benefit in creating family life extension agents and empowering a “corps that is charged with getting research into the hands of people where they are and where the local services are based.”

KEY MESSAGES

Although data from low- and middle-income countries have traditionally been lacking, these gaps are rapidly being filled. As the body of

knowledge grows, a secondary gap remains regarding how best to translate and transport successful programs from one setting to another. Issues including appropriate cultural context, infrastructure, and trained health professional continue to provide impediments to the successful implementation of evidence-based violence prevention programs.

REFERENCES

Barker, G., J. M. Contreras, B. Heilman, A. K. Singh, R. K. Verma, and M. Nascimento. 2011. Evolving men: Initial results from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (images).

CDC (Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention). 2008. Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 57(05):113-117.

Duvvury, N. K., S. Chakraborty, N. Milici, S. Ssewanyana, F. Mugisha, F; et al. 2009. Intimate partner violence: high costs to households and communities. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women.

García-Moreno, C., C. Watts, M. Ellsberg, L. Heise, and H. A. F. M. Jansen. 2005. WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organizaiton.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1994. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for prevention intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Krug, E., L. Dahlberg, and J. Mercy. 2002. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Reza, A., M. J. Breiding, J. Gulaid, J. A. Mercy, C. Blanton, Z. Mthethwa, S. Bamrah, L. L. Dahlberg, and M. Anderson. 2009. Sexual violence and its health consequences for female children in Swaziland: A cluster survey study. The Lancet 373(9679):1966-1972.

UN Women. 2011. Virtual Knowledge Centre to End Violence against Women and Girls. http://www.endvawnow.org (accessed April 10, 2011).