Tasks involved in caring for oneself or others at home may be quite simple, such as taking brisk walks to promote cardiovascular fitness or applying a wrist splint to relieve discomfort from carpal tunnel syndrome. At the other extreme, health care tasks may be far more complex, such as recovery from major surgery or acclimating to new chronic care regimens. Complex health care tasks often require nuanced understanding of a health condition and its treatment as well as the ability to manage symptoms, detect complications, provide hands-on care, offer emotional support, and communicate effectively with health care providers to participate in decisions and manage logistical aspects of health care.

This chapter describes the wide range of tasks related to health care that, with increasing frequency, take place in the home. It describes the demands of those tasks as well as the varying capabilities of caregivers to handle the task demands. Boxes 4-1 and 4-2 provide family vignettes to illustrate varying task demands as well as capabilities.

The chapter also presents methods of analyzing health-related tasks and suggests how the analytic methods may be modified to suit the special considerations associated with home care. Two variants of task analysis are presented, reflecting human factors approaches that enable identification of the capabilities and information that are necessary for performing specific tasks safely and effectively and the factors related to task execution that may be amenable to intervention. An example of a simplified task analysis is offered to illustrate how use of this technique, even at a basic level, can provide health care system and technology designers, evaluators, and train-

BOX 4-1

The Burns Family

Ray Burns is a 59-year-old maintenance supervisor who quit smoking 2 years ago. Forty pounds overweight, he was recently diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes and sleep apnea. Ray reluctantly uses a CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine at night to control his apnea. He has recently acknowledged that his excess weight and lack of regular exercise are threatening his long-term health, and he is serious about renewing the more disciplined approach to diet and exercise that served him well in his youth. He has joined a weight loss group at work and is learning to make healthier choices, monitor his conditions, follow prescribed treatment, and maintain supplies of medications and batteries, test strips, and tubing for his medical devices. He has settled into a daily routine that includes measuring his blood glucose level at home and during the day at work, downloading each reading onto his computer, and generating a trend report to send by e-mail to his doctor. Ray welcomes the structure and encouragement provided by the weight loss program. By adhering to his current diet and exercise plan, he hopes to eliminate his diabetes medication alto ether

Ray’s parents live nearby and are quite frail. Ray’s father, Ed, requires constant supervision due to a stroke he sustained 3 years ago. Ed is a tall and stout man who needs assistance with bathing, dressing, walking, and transfers from bed to chair. Because of difficulty swallowing, he requires tube feedings. Ray’s mother, Dorothy, is small in stature and has emphysema and severe arthritis, so she can help her husband dress but she cannot help with more strenuous tasks, like bathing and transfer ring. Ed and Dorothy receive 6 hours daily of in-home services from the Program for All-inclusive Care of the Elderly (PACE).* Personal care aides help Ed bathe, and an occupational therapist monitors his functional status, oversees his exercise program, and evaluates his use of assistive devices. A nurse recently set up an electronic monitoring system for both Ed and Dorothy, enabling family members and PACE staff to track their medication taking remotely. She is also helping Dorothy use the nebulize and oxygen concentrator that were recently prescribed. Either Ray or his wife Patricia stops by every day to help with tube feedings and oversee Ed and Dorothy’s medication routine.

_____________

*PACE is a capitated system for delivery of in-home, clinical, and adult day care services to nursing home–eligible older adults living in the community (Mukamel et al., 2007).

SOURCE: Clinical experience of committee member Judith Matthews.

BOX 4-2

The Miller Family

Two weeks ago, Lisa gave birth to a son with a congenital hear defect. Lisa is home now, but the baby remains in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) an hour away, recovering from cardiac surgery. He husband, Tom, took a leave of absence from work and has been at the hospital almost constantly, but Lisa must remain at home because he cesarean incision became infected. The home health nurse who visits for wound care helps her frame questions for the NICU staff, with whom Lisa talks several times a day using a webcam-equipped laptop to see how the baby is doing

When Lisa first got home from the hospital, she quickly learned from the visiting nurse how to monitor the healing of her cesarean incision, pack the wound, change the dressing, and take her antibiotic as prescribed. To prepare for the baby’s eventual discharge from the hospital, she and Tom are trying to learn all they can about his condition, treatment, and prognosis. Luckily, they have been able to access quite a bit of information on the Internet. Using the webcam to see and hear their baby or talk with staff of the NICU keeps them apprised of his status when they cannot be at his side.

Lisa and Tom, initially naive about their infant’s heart condition, have learned to ask the NICU staff for more elaborate explanations and to validate the information they have found on the Internet. Lisa keeps a journal chronicling her virtual visits to the NICU as well as Tom’s accounts of his visits there. This keeps events from blurring in Lisa’s mind, and she thinks it will be helpful for future reference.

_____________

SOURCE: Clinical experience of committee member Judith Matthews.

ers with critical information to improve the execution of health care and health management tasks in the home.

TYPES OF TASKS

Health-related tasks involve many aspects of daily function, including personal hygiene and nutrition, safety and comfort, physical fitness, sleep quality, stress management, as well as the planning and coordination to accomplish these personal tasks. Health care–specific tasks may entail obtaining routine health examinations, screenings, and immunizations, instituting prescribed treatment, monitoring disease progression and treat-

ment response, and implementing personal care or therapeutic regimens that accommodate functional impairment and disability. Table 4-1 outlines some health care tasks in four categories: (1) health maintenance—promoting general health and well-being, preventing disease or disability; (2) episodic care—optimizing outcomes of health events that pertain to pregnancy, childbirth, and mild or acute illness or injury; (3) chronic care—managing ongoing treatment of chronic disease or impairment; and (4) end-of-life care—addressing physical and psychological dimensions of dying.

Health Maintenance

People of all ages are advised to engage in various self-help and self-care behaviors that may enhance their general health and well-being or enable early detection and treatment of disease (Zayas-Cabán and Brennan, 2007). These important behaviors include consuming a balanced diet, being physically active, and getting adequate sleep for one’s age or stage of development. Additional personal health habits involve proper hand washing and personal hygiene, appropriate use of vitamin and mineral supplements, adherence to safe sex practices, and avoidance of smoking, illicit drug use, and excessive alcohol consumption. Age- and gender-appropriate physical and oral health examinations, immunizations, and screenings at recommended intervals are disease prevention measures. Using protective gear while driving (e.g., car seats, booster seats, seatbelts, motorcycle helmets), performing hazardous work (e.g., earplugs, headgear, eyewear, clothing, shoes), or engaging in recreational activity (e.g., bicycle helmets, mouth guards, other protective sports gear) is yet another way for people to be proactive about their health.

Activities of Daily Living

Basic activities of daily living (ADLs) are among tasks performed regularly by or for all community-residing individuals. Although this classification of tasks was originally developed to assess independence among persons in institutional settings (The Staff of the Benjamin Rose Hospital, 1959), it is commonly used to describe the functional capabilities of noninstitutionalized individuals. ADLs pertain to personal care and include bathing, grooming, dressing, feeding, toileting and continence, ambulation, and transfers (i.e., moving from one surface to another, such as from bed to chair or wheelchair to toilet). Although it is developmentally appropriate for infants and toddlers to require help with ADLs, assistance with these activities may be required by people of any age who have physical, cognitive, sensory/perceptual, or emotional impairments.

TABLE 4-1 Health Care Tasks in the Home

| Category | Examples |

| Health maintenance |

Personal hygiene |

|

Diet and nutrition management |

|

|

Vitamin and supplement management |

|

|

Exercise regimen |

|

|

Stress management |

|

|

Sleep management (appropriate for age or stage of development) |

|

|

Safe sex practices |

|

|

Avoidance of smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, illicit drug use |

|

|

Use of protective equipment (e.g., gloves, seat belts, bicycle and motorcycle helmets) |

|

|

Regular medical and dental examinations, screenings, immunizations, and care |

|

|

|

|

| Episodic care |

Medication management for minor illnesses |

|

First aid provision for minor injuries |

|

|

Wound care |

|

|

Burn care |

|

|

Recovery from serious injuries |

|

|

Recovery from major incidents (e.g., heart attack, stroke) |

|

|

Recovery from surgeries |

|

|

Allergy treatment |

|

|

Pregnancy management and postpartum recovery |

|

|

|

|

| Chronic care |

Diabetes management |

|

Asthma management |

|

|

Apnea management |

|

|

Nutritional therapy |

|

|

Home infusion therapy |

|

|

Respiratory therapy |

|

|

Home dialysis |

|

|

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) care |

|

|

Tracheostomy care |

|

|

Decubitus ulcer (pressure sore) care |

|

|

Stoma (e.g., colostomy, ileostomy, ureterostomy) care |

|

|

Catheterization and related care |

|

|

Rehabilitation regimens prescribed by physiatrists or physical, occupational, vocational, or speech therapists |

|

|

Psychotherapeutic regimens |

|

|

|

|

| End-of-life care |

Pain management |

|

Symptom management |

|

| Care recipient and family counseling |

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Additional tasks essential to day-to-day living are called the instrumental activities of daily living, or IADLs (Lawton and Brody, 1969). These involve tasks related to independence, including household management, meal preparation, cleaning, laundry, shopping, and handling of personal finances. Performance of these types of household activities may be hampered temporarily or permanently by disabling health conditions.

Care of Injury, Illness, or Impairments

Tasks necessitated by injuries, illnesses, or impairments affect the rhythm of everyday life for millions of people. Some health care tasks are simple and intrude little on normal day-to-day life. Others are highly disruptive, at least temporarily if not permanently, and require clinical competencies that were once strictly within the purview of health care providers in hospitals, clinics, or doctors’ offices. These tasks may be anticipated, or they may arise unexpectedly. They may diminish in intensity over time, or they may require prolonged performance.

Whether a father administers phototherapy at home using a bili light to resolve jaundice in his newborn, a mother performs tracheostomy care for her school-age child with bronchopulmonary dysplasia, or a woman empties the drainage tubes extending from her abdominal incision, the people who perform these and other condition-specific health care tasks at home do so for many reasons. Their efforts may be directed toward managing symptoms, controlling or curing disease, or monitoring response to prescribed treatment. The tasks may also involve assessment of possible complications or implementation of elaborate ADL and IADL routines necessitated by severe disability.

Episodic Care

Episodic care is medical treatment needed for a short-term condition, illness, or injury. Episodic care may require care recipients or caregivers to quickly learn care procedures and operation of medical equipment, and it may require temporary home adjustments to adapt to short-term needs or activity limitations. Episodic care does not require long-term lifestyle changes, although, for example after a stroke or heart attack, episodic care may transition to chronic care. Some examples of tasks for episodic care include medication management, pain management, wound and skin care for incisions and lacerations that require cleansing and dressing changes, adherence to standard precautions for infection control (Siegel et al., 2007), sanitation or sterilization of equipment, and performance of

physical, occupational, and speech therapies for maintaining or restoring function.

Chronic Care

Chronic care is needed to deal with long-term, ongoing conditions or diseases (e.g., asthma, congestive heart failure, cystic fibrosis, kidney disease, diabetes, impairments) and may require lasting adjustments by all household members. Chronic care is complex, and, in order to be effective and safe, it frequently requires careful planning. It often requires learning and continuing to perform new procedures and equipment operation. It may require both the care recipient and others in the household to make long-term changes in lifestyle (e.g., diet, exercise, activities of daily living, household responsibilities) and to continuously monitor the care recipient’s condition. It also is likely to require the care recipient and informal caregivers to establish and maintain effective long-term relationships with professional caregivers. Chronic care is often more challenging and stressful than episodic care because of its greater effects on daily living and its continuing burden.

Although many of the tasks mentioned above for episodic care exist for chronic care, such care often requires regular sustained tasks and tasks involving medical devices. Some examples of tasks for chronic care include provision of nutritional support delivered enterally (e.g., via a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube into the stomach or via a jejunostomy tube into the small intestine) or parenterally (i.e., intravenously); intravenous infusion therapies (e.g., prescription medication, fluid replacement, Epogen therapy, and blood products); care required for oxygen and other respiratory therapies, including cleaning and storage of equipment (e.g., oxygen tanks and concentrators, nebulizers, positive airway pressure [CPAP and BiPAP] masks and machines); management of mechanical ventilation equipment; tracheostomy care and suctioning for removal of airway secretions; care for a stoma (e.g., colostomy, ileostomy, ureterostomy) and the apparatus used to collect body waste (i.e., feces or urine); diapering, enema administration, clean catheterization, or indwelling or suprapubic catheter care; management of continuous vacuum drainage systems; and implementation of psychotherapeutic regimens.

End-of-Life Care

The term “end-of-life care” is applicable only when it is known (at least to the caregivers) that the care recipient is dying, and care is provided in the context of this knowledge. This care is often palliative, designed to

maintain the care recipient’s comfort and reduce pain and distress, although in some cases active treatment is continued. Many of the tasks of end-of-life care are the same as those of chronic care, but the conditions under which they are performed are different. The caregivers must provide care under the emotional burden of knowledge that death is approaching, and difficult decisions about treatment must often be made. Unique tasks include counseling of the family and the care recipient.

Coordination of Care

Tasks for coordinating care are logistical in nature: scheduling medical or dental appointments, arranging for transportation, ordering prescriptions and other medical supplies, renting or purchasing medical equipment, arranging for pick-up or delivery of supplies or equipment, managing health-related finances, and maintaining personal health records. In addition, informal caregivers must interact, to varying degrees, with physicians and other health care professionals about care recipient status and care needs, hire nurses and aides, communicate and negotiate with other family members about care decisions, and provide companionship and emotional support to recipients. Informal caregivers are also called on to coordinate services from various health and human service agencies and make decisions about service needs and how to access them (Bookman and Harrington, 2007).

Skills for Coordinating

Attending to personal health at home requires skills for garnering resources, organizing health care tasks, and communicating effectively with the other people involved (in person, by telephone, or by some electronic means). In contrast to clinical environments in which health care management is largely the province of health care providers, primary responsibility for managing health care at home is borne by care recipients or their family members. Some people manage care systematically and are articulate when dealing with their health, whereas others are disorganized and communicate poorly. Moreover, people who handle other aspects of daily life quite well may find it difficult, at least initially, to transfer these skills to their handling of health matters at home.

Coordinating services needed to support care recipients in the home or as they transition from one care setting to another is particularly challenging for caregivers (Levine et al., 2010). Even seasoned health professionals with detailed knowledge of and experience with health care systems find care coordination for family members a formidable challenge (Kane, Preister, and Totten, 2005). The intensity of tasks associated with coordination of

care has been described as contributing to a blurring of the boundaries between informal and professional caregivers, as family members begin to assume professional attitudes toward the care of their loved ones to ensure their needs are best met (Allen and Ciambrone, 2003).

Formal Caregivers as Role Models

Formal caregivers often demonstrate and supervise repeated practice of proper techniques for previously untrained persons. Personnel in home visiting programs routinely show individuals and members of their households how to modify daily living activities to accommodate functional limitations, perform medical procedures or therapies, watch for changes in health status, and troubleshoot clinical or technical problems that arise. Formal caregivers expend considerable effort bolstering the health management capabilities of persons who care for themselves or provide assistance to others as informal caregivers. They do so by offering guidance and encouragement while modeling and reinforcing behaviors, thereby enabling persons without prior health training to anticipate, prevent, or address health-related problems on their own. By observing formal caregivers communicating with others on their behalf, care recipients and informal caregivers can gain confidence in their own ability to coordinate care among providers.

TASK DEMANDS ON CAPABILITIES

The array of tasks performed as part of health care as well as daily living involves many domains of human capability. Indeed, embedded in these health-related tasks are myriad subtasks that place demands on the physical, cognitive, sensory/perceptual, emotional, and communication capabilities of those performing them and require flexibility in execution. The examples here illustrate how multiple domains of human capability may be activated simultaneously in accomplishing even seemingly simple tasks, such as bathing, check writing, and taking medication as well as caring for surgical incisions at home.

Bathing independently involves multiple actions that require balance, strength, and flexibility for coordinated movement of the limbs and trunk, especially for quick recovery from slips or trips on hard and wet surfaces. It requires executive cognitive function and psychomotor skills that enable performance of each step in logical sequence and with insight into one’s limitations and risk of falling, thus underscoring the important interaction among the person, the environment, and the bathing task itself (Murphy, Gretebeck, and Alexander, 2007).

Although often mundane and influenced by cultural expectations for role and gender, IADLs are actually quite complex and require capabilities

in several domains. For example, bill paying goes well beyond the physical act of paying with cash or credit card, writing a check in the correct amount, or making a payment online. It requires capabilities in the cognitive domain (organizing bills received, remembering to pay them when due, interpreting invoice information, computing balances, and determining whether sufficient funds are available), the physical domain (manipulating the cash, check, credit card, or electronic device used for payment), the sensory/perceptual domain (seeing and reading statements for the bill and source of funds for payment), and the communication domain (dealing with vendors and account representatives in person, online, in writing, or by phone).

Taking medication, whether prescribed by licensed health professionals or self-prescribed, is among the most common health care behaviors performed by individuals of all ages. For many people, adhering to a medication regimen is difficult, often due to its complexity or inconvenient timing, or as a result of simple forgetfulness, belief that the regimen lacks therapeutic benefit (Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005), or cognitive decline (Stilley et al., 2010). Successful medication taking involves the correct person receiving the correct dose administered using the appropriate technique at the right time under the proper conditions (e.g., with food, while sitting up, or before cleansing and dressing a painful wound). Medications may enter the body in various ways—by topical application, oral or rectal administration, subcutaneous or intramuscular injection, inhalation, or peripheral or central venous infusion, among others. Lippa, Klein, and Shalin (2008) provide an example of the cognitive complexity of self-management of diabetes, including discussion of medication management and other tasks. Thus, psychomotor skills, as well as adequate vision, tactile sensation, knowledge, memory, and judgment, are needed to administer medications safely and effectively, regardless of who performs the task.

Caring for a surgical incision at home following a total knee replacement is an example of an episodic care task that involves many capability domains. This task can be divided into many subtasks that include placing wound dressing supplies and a trash receptacle within reach, washing hands before and after the procedure, positioning the knee for full view of the wound, donning gloves, removing and disposing of the soiled dressing, cleansing the incision, applying fresh bandages, wrapping the knee with gauze to secure the dressing in place, and, finally, removing the gloves and disposing of them properly (physical capabilities). In addition to these psychomotor skills, sufficient health literacy is needed to understand the care instructions, follow the steps involved in changing the dressing in proper sequence, gauge whether healing is occurring as expected, and solve any problems that arise (cognitive capabilities). Vision is needed to inspect the incision for signs of infection and healing, and touch and smell enable

detection of excessive warmth, swelling, or foul odor that may indicate infection or poor healing (sensory/perceptual capabilities). Stress imposed by emotional or physical discomfort, limited mobility, disruption in usual routines, and uncertainty about return to normal function activates one’s repertoire of coping strategies (emotional capabilities), and the ability to report progress or concerns to health care providers (communication capabilities) may influence the rate and course of recuperation.

APPLYING A HUMAN FACTORS APPROACH

The diversity of persons engaged in health care in the home and the heterogeneity of health-related tasks performed in the context of home and family present many challenges for achieving an ideal fit between task demands and human capabilities. When task demands exceed an individual’s physical, cognitive, emotional, sensory/perceptual, or communication ability to perform the task, the potential for adverse outcomes increases. Identifying precisely where mismatches exist—that is, where there is lack of fit between what is required to perform safe, efficient, and effective care and the capabilities of the people who provide that care—makes possible the crafting of a plan for tailored intervention. Such a plan could include hands-on training, assistive devices, additional caregivers, and use of various printed, audiovisual, or interactive (telehealth) tools that provide guided prompting or access to professional and peer support. Human factors approaches can help delineate where targeted intervention can enable safer and more efficient and effective task completion.

In order to reduce the probability of errors and improve the efficiency of care, it is first necessary to assess both the task demands and the capabilities of the individuals performing the tasks to determine where potential mismatches occur and, second, to design the system or the processes to reduce the mismatch.

Assessment Tools

A number of tools are available for assessing functional capabilities of individuals, providing objective data to assist with targeting individualized rehabilitation needs or planning for specific in-home services, such as meal preparation, nursing care, homemaker services, personal care, or continuous supervision. These functional assessment tools are often used by clinicians to focus on a person’s baseline capabilities, facilitating early recognition of changes that may signify a need either for additional resources or for a medical work-up (Gallo and Paveza, 2006). In research, these tools are frequently used to describe sample characteristics or to enable longitudinal evaluation of the impact of a disease or treatment on functional status.

One such instrument is the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale, which is typically used to assess independent living skills among adults and measures eight domains of function (Lawton and Brody, 1969). Another functional assessment tool used to measure capacity to execute basic activities of daily living in the adult population is the Katz Index of ADLs (Katz et al., 1970; Katz, 1983), which assesses level of performance in six functions: bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and feeding. Additional tools exist for measuring the functional status of children, particularly relative to their capacity and readiness for learning.

A number of other clinical and research tools exist that permit assessment, in general, of individuals’ cognitive and physical function, emotional status, and level of preparedness for the health care and health management tasks they need to assume. An important limitation of all these measures, including those of ADL and IADL capabilities, is that they commonly do not evaluate the extent of correspondence between specific capabilities of the individual and the capabilities needed to perform each of the specific tasks and subtasks required for managing his or her health at home. Gaining a more nuanced appreciation of the specific capabilities required for specific tasks or subtasks is needed, and human factors offers established techniques for accomplishing this objective.

Application of Task Analysis

Task analysis, as explained in the following sections, involves human factors methodology developed for this purpose. Although comprehensive description of all task analysis techniques is beyond the scope of this chapter, the goal here is to illustrate the usefulness and importance of the task analysis approach.

The effectiveness in executing a given task—that is, low error rate and high efficiency—for most health-related activities at home is predicated on the condition that the capabilities of the individual, or actor, performing the task meet or exceed those demanded by the task. Any discrepancy must be mitigated by one of several solutions, including training the users, deploying individuals with greater capabilities, or introducing technology or other changes to transform a demanding task into an easier one requiring lower levels of user capability. Improving the skills of individuals or their caregivers may not always be feasible, but technology or task redesign can simplify a task or reduce the need for special skills. Technology can support tasks that are otherwise difficult to perform or minimize the probability of errors and adverse events.

Overview of Task Analysis

Task analysis is a tool used in human factors engineering to help optimize the functioning of a system. In order to develop specifications for viable systems or procedures, it is important to understand the demands of the tasks as well as potential pitfalls that may lead to adverse situations. The purpose of task analysis is to identify the prerequisites, demands, resources, workflow issues, and potential error-prone situations involved in execution of a task. Task analysis comprises a collection of formal methods that enable systematic analysis of the actions and interactions involved in order to minimize omission of specific steps and the potential for erroneous actions.

Development of the task analysis methodology was initially motivated by the need for formal human factors methods in industry and the military, for which the value of maximizing safety and performance is particularly high. In aviation, nuclear plants, or military operations, failures in task execution by humans and machines can lead to catastrophic effects (Fitts and Jones, 1947). Task analysis has since been extended to a variety of applications, ranging from health care to computer interfaces (Dix et al., 2004). The results of these analyses are typically used to develop system requirements for the design or redesign of systems, and also to develop checklists and training procedures. For example, task analysis has been used to study system interactions with people who have physical or cognitive impairments, and the results of the analysis have been used to develop training programs tailored to the needs of these individuals. Currently, the success of task analysis applied to health care in the home depends on the analyst’s human factors expertise, domain knowledge regarding health care and health management at home, understanding of tasks and task demands, and direct experience with task performance (Drury, 2010).

A typical task analysis process has three stages: (1) acquisition of information, (2) analysis of the data, and (3) development of a representation of the results that can be used to guide the design of devices, processes, or selection of personnel.

Gathering data enables the analyst to break the task into its components and characterize each of these in turn. Task analysis conducted with any degree of rigor first entails developing descriptions of the tasks based on use cases, or scenarios, such as that depicting the Burns family in this chapter (see Box 4-1). The task description specifies the objective to be achieved by performing the task, what is required of the actor (task demands) regardless of who performs it, the system or environmental feedback resulting from task performance, and the interrelationship among subtasks. It further specifies where errors and inefficiencies are likely to occur when capabilities fall short of task demands. There are two general

approaches to data acquisition: (1) empirical observations and (2) logical decomposition of the task objectives and characterization of any available contextual information. In general, the most complete and reliable task analysis process relies to some extent on both approaches if empirical data are available. If any of the tasks cannot be performed without use of some type of technology and the technology is not available for task observation, then the analysis may be based entirely on the logical approach or on observation of the task performance on a similar system or on a prototype. In these situations, the task analysis results will inform the subsequent design of technological solutions.

Task Analysis and Home Health Care

Classification of tasks is an important component of both the task analysis process and the development of solutions, and it supports two goals: (1) systematically classifying and creating an ontology of tasks usually leads to more complete sets of tasks and (2) determining similarity among tasks suggests the possibility of finding similarity among solutions. The first formal step in the analysis of the needs and requirements of persons managing health care at home is to identify the critical tasks that are required to maintain independence and maximize quality of life. Several studies have deployed empirical approaches to determine sets of tasks that are important to different populations at home (Clark and Rakowski, 1983; Wilkins, Bruce, and Sirey, 2009). The set of tasks identified by each study generally depended on the specific goals of the study, as well as on the populations evaluated and other factors. The different lists comprise tasks that vary in level of detail. These lists informed the taxonomy shown in Table 4-1.

Given the diversity of health care that occurs in the home, an analyst must consider a wide range of situations. Even if a particular intervention is designed for a caregiver who is present with the care recipient, the task analysis process must consider the possibility of remote caregivers’ involvement as well. Remote caregivers, such as adult children who live far from aging parents, may play key roles in care coordination, socialization, and many other aspects of care. Advances in technology present increasing opportunities for remote caregivers to provide support to individuals at home (see Chapter 5).

Although the general approach in task analysis is agnostic as to who performs the task (Drury, 2010), in the domain of health care in the home the specific components of the tasks may depend on the particular actor, or person performing the task. For example, the task of bathing another person, as might be performed by a parent caring for an adult child recovering from a traumatic injury, would be different from the task of bathing oneself. Thus, for many tasks in the home care domain, it is necessary to consider task demands in relation to the capabilities of the specific actor who performs the

task. This actor may be an individual capable of self-care, an individual in need of assistance (care recipient), an informal caregiver (on-site or remote), a formal caregiver (on-site or remote), or some combination of these.

Another important aspect of tasks that needs to be considered in the task analysis process for home care involves estimates of the utility of specific tasks. In contrast to a typical industrial situation in which task utilities are frequently implicit, in the home situation, not all health-related tasks competing for resources are equally important. For example, some tasks are essential for survival, whereas other tasks merely enhance quality of life. Determination of utility is important for resource allocation and prioritization of different tasks. In a resource-limited situation, the more critical tasks must be performed first. When safety and accurate decision making rather than resource scarcity are at issue, greater emphasis needs to be placed on subtasks that are critical.

The empirical approach to task analysis can include observational studies, questionnaires, analysis of errors, or any combination of these. A simple task analysis of medical device use may include identification of the subtasks involved in performance of a task (i.e., task decomposition), the information required by the user to complete each, the feedback that the device or environment provides, and the potential problems that could arise if the task were not carried out properly. For example, Rogers et al. (2001) performed a task analysis of using a blood glucose meter, which found that setting up and checking the meter and testing blood involved 52 subtasks; Table 4-2 lists only the 10 subtasks associated with using the lancing device. The analysis showed that many of these subtasks required knowledge of how to handle the device and knowledge of correct procedures for lancing a finger. This result suggests a significant need for effective device instructions and, for at least some users, training.

A classic example based on self-report questionnaires and videotaped observation is a study by Czaja, Weber, and Nair (1993) in which task analysis was applied to bathing, one of the basic activities of daily living. Bathing was recognized as a problem for frail older adults (i.e., 23 percent of older adults living at home at the time needed help with bathing—Dawson, Hendershot, and Fulton, 1987), but the key factors were not known. Using task analysis in conjunction with an empirical approach, these investigators identified specific functional problems (e.g., difficulty reaching or lifting) and suggested possible solutions (e.g., grab bars). An alternative way to collect specific activity-related information involves systematic exploration of the relationship among three different classes of descriptors, namely person, task, and environment (Strong et al., 1999). This classification of input information is useful in that it guides consideration of various aspects that are likely to affect performance. The result of this exploration, however, is generally equivalent to a competent task analysis.

TABLE 4-2 Results of a Task Analysis for Using a Lancing Device

|

|

||||

| Subtask No. | Subtask | Task/Knowledge Requirements | Feedback | Potential Problems |

|

|

||||

| 1 | Remove the lancing device cap | Correct procedure | Tactile | Lancing device cap not removed |

| 2 | Insert a sterile lancet in the lancet holder | How to insert lancet | Tactile | Lancet inserted incorrectly; sharps injury |

| 3 | Twist off the lancet protective cap | How to remove protective cap | Tactile | Protective cap not removed |

| 4 | Replace the lancing device cap | How to replace lancing device cap | Tactile | Lancing device cap not replaced or replaced incorrectly |

| 5 | Cock the lancing device | How to cock the lancing device | Lancing device clicks when cocked [audible] | Lancing device not cocked |

| 6 | Wash your hands | Correct procedure | None | Hands not washed; possible infection |

| 7 | Hang your arm at your side for 10-15 seconds | Correct procedure; proper length of time | None | Don’t hang arm at side; unable to get good blood flow to fingers |

| 8 | Hold the lancing device against the side of a finger | Correct location to prick finger | Tactile | Lancing device not held against finger; unable to get blood |

| 9 | Press the release button | Location of release button | Tactile (feel finger pricked) | Unable to prick finger |

| 10 | Squeeze the finger to obtain a large, hanging drop of blood | Correct procedure | Blood produced [visual] | Not enough blood produced; blood is smeared rather than hanging |

|

|

||||

SOURCE: Rogers et al. (2001).

Hierarchical Task Analysis

Hierarchical task analysis is the task analysis methodology used most frequently in industrial settings. Although developed originally for the chemical industry (Annett and Duncan, 1967), it has been applied in a variety of situations ranging from aviation to the training of individuals

with cognitive impairments. A comprehensive description of hierarchical task analysis can be found in Shepherd (2001) and Annett (2003), but in this chapter we present the basics of the approach and use two examples to illustrate its application. Using hierarchical task analysis can help identify possible conditions that could lead to adverse events and can support the development of physical or cognitive assistive devices that would help in the execution of these tasks or the development of training procedures. Hierarchical task analysis starts from a set of main goals and “uses a systematic goal decomposition methodology until a sufficient level of detail is reached” (Drury, 2010). The result of the analysis is generally a hierarchical structure that can be represented either graphically (e.g., in block diagrams or signal flow graphs) or in an outline-like formatted table.

The first example of a hierarchical task analysis is for washing hands, from a project that focused on the development of cognitive aids to enable individuals with mild cognitive impairment to perform a variety of simple tasks (Mihailidis et al., 2008; Hoey et al., 2010). The project envisioned a system of video cameras and sensors that would depend on adaptive artificial intelligence algorithms to infer an individual’s actions and provide guidance if needed. The development of the system required fairly detailed task analysis in order to infer the correctness of each action and its sequences.

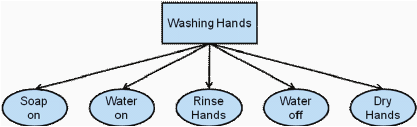

The results of task decomposition for hierarchical task analysis to the task of washing hands are shown in Figure 4-1. In Figure 4-1a, the main task is divided into a set of component tasks, but the order of execution is not a part of this representation. If this decomposition were used only to prescribe a procedure for training, it would be sufficient to arrange the component tasks in a single linear sequence. However, the cognitive assistive application would require the system to include all valid paths, because it would be inappropriate to generate corrective feedback in situations in which the actor happened to choose a different but also valid sequence.

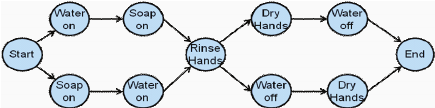

Rather than specifying exponentially more complex plans, it is better to represent the results of task decomposition in terms of a state diagram that is similar to those used in link analysis (Drury, 1990; Stanton, 2006; Wolf et al., 2006). An example of the state-transition diagram (state-space representation) is shown in Figure 4-1b. Each node in this graph represents either an activity, such as a component task, or a state that resulted from completing predecessor tasks. Any sequence from “Start” to “Finish” in this diagram is a valid sequence that would result in a successful completion of the task. By traversing the different paths, it is possible to examine each state and action for the user capabilities and task demands.

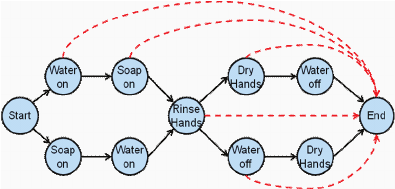

The state transition-based representation is also very useful in detecting possible sequencing errors. One way to determine all possible errors due to sequencing is to create a complete graph, that is, connect each node to all

a. The first level of task decomposition for hierarchical task analysis for washing hands.

b. A state-transition diagram of task decomposition for hierarchical task analysis for washing hands.

c. A state-transition diagram of task decomposition for hierarchical task analysis for washing hands with possible erroneous transitions indicated by dashed lines.

FIGURE 4-1 Task decomposition for hierarchical task analysis of the task of washing hands.

SOURCE: Adapted from Hoey et al. (2010). See Hoey et al. (2010) for more details on how these results can be used in the design of assistive systems.

other nodes, identify which of these transitions are erroneous, and estimate the seriousness of the error. The graph in Figure 4-1c illustrates a small subset of the possible errors using dashed lines. The seriousness of the errors can be illustrated by comparing forgetting to dry hands with forgetting to rinse off the soap and turn off the water.

The discussion thus far has treated task analyses and their results as being deterministic. While this is appropriate when determining procedures for controlled situations (such as in many industrial, military, and medical applications), for health care in the home situations, the tasks, as well as their sequencing, need to be described in probabilistic terms, in which the execution of different components, their success, and their order are uncertain and therefore better described by their probabilities. This can be easily implemented in a graph-based representation similar to that used for link analysis in industrial applications. The probabilistic representation would enable the development of technology-based aids that would, in addition to providing guidance to the individual, enable the system to make inferences about his or her capabilities.

Lane, Stanton, and Harrison (2006) have demonstrated a more complex example of task decomposition for hierarchical task analysis applied to administration of medications in hospital settings (Lane, Stanton, and Harrison, 2006). The resulting hierarchy of tasks is shown in Figure 4-2. For the sake of clarity, this diagram shows only the coarsest decomposition of the tasks at the highest levels of the hierarchy. Although this specific analysis involves hospital settings, it may be adapted for similar analyses in residential environments. The analysis in this case was performed using logical analysis in combination with practical experience by a trained pharmacy technician and was then reviewed by two nurses. This example illustrates that errors in medication administration may occur in a number of ways, even if there is no mismatch between task demands and an actor’s abilities, and that errors can be anticipated using hierarchical task analysis in conjunction with expert assessments and models of human cognitive abilities.

Cognitive Task Analysis

As illustrated by the examples given above, in many health care situations in the home, the most critical user capabilities are cognitive rather than physical or sensory/perceptual. Although the importance of other user capabilities is hard to overestimate, many home care tasks depend heavily on the cognitive functions and processes of the individual performing them. The goal of the cognitive task analysis is to ensure that the actor has the required prior knowledge, necessary real-time information, cognitive skill, and sufficient resources (such as time) to perform the task. The

Permission was not granted by the copyright holder to be posted online.

Figure 4-2 appears in the hard copy of the book only.

FIGURE 4-2 Example of a result of task decomposition for hierarchical task analysis for medication administration in a hospital setting.

SOURCE: Reprinted from Lane, Stanton, and Harrison (2006).

match between task demands and the actor’s capabilities can be determined through use of cognitive task analysis. Cognitive task analysis may be considered task analysis applied to the cognitive domain, with the added difficulty that not all actions and component tasks are directly observable and some must therefore be inferred from performance or by using a variety of knowledge elicitation techniques.

The products of cognitive task analysis are the knowledge structures and the cognitive processes that underlie individuals’ decisions and actions. Knowledge structures are methods for representing concepts and the relationships among them, such as domain knowledge of a disease or medication or basic knowledge of information-seeking strategies. For example, in order to adhere to a medication regimen, a care recipient and/or caregiver must know the conditions that call for drug administration (e.g., “evening before dinner,” “high blood pressure,” “high glucose concentration”). In particular, performance of activities associated with, for example, an adolescent with Type 1 diabetes requires considerable knowledge of a variety of interrelated concepts ranging from the significance of glucose concentration and the requirements for glucose monitoring to maintenance and troubleshooting of the monitoring equipment.

Knowledge structures comprising concepts and associated relationships may be represented as ontologies (Gruber, 1993) or semantic networks.1 These network-like representation techniques applied to cognitive task analysis are often referred to as concept maps (Novak, 1990; Castellino and Schuster, 2002). Like semantic networks, concept maps are used frequently to characterize complex knowledge structures using graphs, with concepts as nodes and connections between nodes indicating relationships between two connected concepts. For example, physical exercise and glucose level are linked in the case of a diabetic individual, and this link must be incorporated into his own and his caregivers’ knowledge structure.

Cognitive processes are typically covert computation-like operations, such as storing items in working memory or reasoning, that a care recipient or caregiver must perform to accomplish a task. Examples of cognitive processes include searching memory for appointments or medications, directing one’s attention to the particular source of visual or auditory information, recognizing alerts, etc. A subset of these processes is associated with perception, but a number of the more complex cognitive processes, such as planning, problem solving, and decision making, are generally subsumed under the term “executive function.”

As for any type of task analysis, in cognitive task analysis, the development of knowledge structures (such as concept maps or semantic networks)

_____________

1Software tools have been developed to support generation and use of ontologies and concept maps, for example, IHMC CmapTools (http://cmap.ihmc.us/).

and specification of the underlying cognitive processes require an analyst to collect data regarding the specific tasks and contexts to be included and analyzed. The acquisition of this knowledge may require deploying a number of diverse data-gathering techniques that facilitate extraction of information from the individuals involved in executing the task. These data elicitation approaches typically include interviews, self-reports, unobtrusive observations, and automated data capture by sensors and computers. Each of these data acquisition techniques has its advantages and disadvantages. Because of the covert nature of cognitive processes, the analyst must carefully structure any interviews to reduce subjective effects due to the interviewers’ biases and preconceived notions.

One useful approach to cognitive task analysis is to hypothesize a computational model of the relevant cognitive processes (e.g., perception, memory, decision making) and then construct a program to perform the task. Although the specific aspects of such analysis depend on the particulars of the adopted model, this general approach is likely to lead to a more complete characterization of the task and the task requirements.

One example of a model that enables cognitive task analysis in a similar manner to hierarchical task analysis is GOMS (Card, Moran, and Newell, 1983) and its derivatives. GOMS is a human information processing model that stands for Goals, Operators, Methods, and Selection rules. Much like hierarchical task analysis, the application of GOMS leads to a decomposition of cognitive tasks into component tasks until the desired level of analysis is reached. Many other models of cognitive processes can be used to characterize individuals’ cognitive activities and therefore can be used for cognitive task analysis (Crandall, Klein, and Hoffman, 2006). With advances in sensing and inference technology, cognitive task analysis will be increasingly useful in guiding the design of human-system interfaces and cognitive aids.

Applications of the Results of Task Analysis

Task analysis is a powerful, though sometimes complex, human factors technique that can be used for gaining a nuanced understanding of what is required to perform the array of health-related tasks that are increasingly performed at home and for detecting when individuals lack the capabilities necessary to perform these tasks safely, efficiently, and effectively. The invaluable insights gained through this technique can be used to improve the systems, processes, and training needed to support health care and health management in the home. By taking into account the factors that influence task performance, core elements of system design can be tailored to accommodate the expected users and minimize or eliminate the mismatch between task demands and human capabilities.

The results of task analyses can inform design modifications of medical devices and health information technologies used in the home, either during their initial development or for subsequent versions of these products. By helping designers to anticipate where target user groups may commit errors with or misuse their systems, the results of task analysis can facilitate timely alteration of design specifications, ideally prior to usability testing and commercial deployment. Likewise, these findings can inform device labeling, thereby increasing the likelihood that labels will be intuitive, or user-friendly, for diverse populations whose ability to see, read, hear, and understand instructional cues or label content may vary widely.

Training of individuals to perform various health-related tasks at home can also be strengthened by applying the results of task analysis. Thorough understanding of what it takes to perform health-related tasks properly in the home environment, coupled with broad appreciation of the varying amount of preparation people may have to assume such responsibility, supports development of training materials at several levels. Although many training materials are available, particularly on websites and in print format, they tend to be prescriptive, focusing more on what must be done and less on the capabilities essential to the task. They also tend to be condition-specific, of varying quality, and difficult to locate.

Most importantly, performance supports or job aids informed by task analysis can be developed to guide people who have little or no preparation for performing the task or who suffer cognitive declines. These aids can range from sketches that depict essential components or steps of the task to textual or audiovisual materials that convey the same information in a language and vocabulary that is easily understood by persons with low health literacy. Such aids can also help address variations in cognitive abilities due to the effects of fatigue, pain, drugs, or disease progression. We expect that the results of task analysis will shortly become a key tool for developing intelligent, networked cognitive assistive devices that will compensate for the cognitive limitations of the care recipients and their caregivers.

Checklists developed from task analyses are a particularly effective kind of performance aid for prompting correct execution of health-related tasks. Checklists that may be useful for home-based health care can be divided into two types (Gawande, 2009):

- READ-DO: a step-by-step list of procedures to be followed in sequence. This type of checklist is best suited for tasks involving details that people may not remember, particularly when under emotional stress. Examples of these tasks are wound care, infusion pump use, and automatic external defibrillator (AED) operation.

- DO-CONFIRM: a list of tasks that actors check off as or after they complete them. These lists are most appropriate when a number

of people perform jobs separately or asynchronously and use the checklist afterward to confirm that the job was done correctly. An example of this type of list might be used to guide transitions of care from hospital to home, which involves a number of people with responsibilities for various tasks.

For persons who are not health care providers but whose experience or education has prepared them to some extent to perform the task, greater visual detail or more complex language may be used for training. Among formal caregivers new to health care in the home, training may need to emphasize insightful appraisal of their own capabilities and those of others (e.g., persons whom they supervise, such as people who receive care, family members, and coworkers on their team) and promote strategies for enhancing task performance. For formal caregivers with extensive experience providing health care in the home, training in the form of continuing education can incorporate methods for promoting these same assessment and tailored intervention skills. Health professional education and training programs for direct-care workers in health care in the home can likewise benefit from curricula infused with information gained from task analysis.

An example of the use of task analysis to support the efficient and effective selection of devices for home health care can be developed from Table 4-2, showing the subtasks involved in using a lancing device to obtain blood for monitoring glucose levels. A task analysis for use of the lancing device could be developed and included in a device database, like the one recommended in Chapter 7. Then, if assessment instruments were readily available to evaluate the capabilities of care recipients, as also recommended in Chapter 7, such an evaluation could be done on each recipient before a care plan is developed.

Then, whenever a provider was considering recommending (for example) that lancing device for a care recipient, the task demands of the device and of alternative devices performing the same function could be retrieved from the database and compared with the care recipient’s capabilities. This would allow the provider to determine whether that device or some other would be the best fit and whether the care recipient would need training, support, or assistance in using the device that is finally chosen. A skilled person, perhaps an appropriately trained occupational therapist, would be needed to evaluate the information on task demands and recipient capabilities, but a new task analysis would not be needed for each device/user analysis.

As an experience base developed, device designers could obtain feedback on the mismatches commonly found between the devices they have marketed and the actual capabilities of those who need to use the devices,

informing the design of future devices to ensure their usability by the population in need of them.

In summary, human factors approaches applied to the ever-increasing array of health-related tasks performed in the home can be used to improve the systems, processes, and training available for their successful completion. This is not to say that a task analysis is done for each and every care recipient and caregiver. We recognize that would be prohibitively expensive and probably unnecessary. Ideally, task analyses are developed for specific tasks (e.g., glucose monitoring) and would specify the subtasks and capabilities needed to perform the task. Developers could use these analyses, in conjunction with other knowledge from human factors research, to recognize potential limitations in user capabilities and to improve the design of medical technologies as well as medical procedures and trainings that better leverage existing capabilities to complete tasks. These analyses should then be refined as the tools, technologies, and procedures associated with the tasks are designed, developed, or changed. In-home assessment tools could draw on these analyses to measure if potential task performers have the capabilities to perform the tasks. When they do not, a professional, such as an occupational therapist, can consider the options for matching tasks and performers: adapting devices or their operational requirements, choosing different devices, training, professional support, etc.

REFERENCES

Allen S., and Ciambrone, D. (2003). Community care for people with disability: Blurring boundaries between formal and informal caregivers. Qualitative Health Research, 13(2), 207-226.

Annet, J. (2003). Hierarchical task analysis. In E.E. Hollnagel (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive task design (pp. 12-36). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Annett, J., and Duncan, K.D. (1967). Task analysis and training design. Occupational Psychology, 41, 211-221.

Bookman, A., and Harrington, M. (2007). Family caregivers: A shadow workforce in the geriatric health care system? Journal of Health Politics and Policy Law, 32(6), 1005-1041.

Card, S.K., Moran, T.P., and Newell, A. (1983). The psychology of human-computer interaction. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Castellino, A., and Schuster, P. (2002). Evaluation of outcomes in nursing students using clinical concept map care plan. Nurse Educator, 27(4), 149-150.

Clark, N.M., and Rakowski, W. (1983). Family caregivers of older adults: Improving helping skills. Gerontologist, 23(6), 637-642.

Crandall, B., Klein, G., and Hoffman, R.R. (2006). Working minds: A practitioner’s guide to cognitive task analysis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Czaja, S.J., Weber, R.A., and Nair, S.N. (1993). A human factors analysis of ADL activities: A capability-demand approach. Journal of Gerontology, 48, 44-48.

Dawson, D., Hendershot, G., and Fulton, J. (1987). Aging in the eighties: Functional limitations of individuals age 65 years and over. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad133acc.pdf [March 31, 2011].

Dix, A., Finlay, J., Abowd, G., and Beals, R. (2004). Human computer interaction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Drury, C. (2010). Frameworks for understanding home caregiver tasks. Paper presented at the Workshop on the Role of Human Factors in Home Healthcare, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC.

Drury, C.G. (1990). Methods for direct observations of performance. In J. Wilson and E.N. Corlett (Eds.), Evaluation of human work: A practical ergonomics methodology (2nd ed., pp. 45-68). London: Taylor and Francis.

Fitts, P.M., and Jones, R.E. (1947). Analysis of factors contributing to 460 “pilot error” experiences in operating aircraft controls. Aero Medical Laboratory, Air Materiel Command, Wright Patterson Air Force Base (Vol. Memorandum Report TSEAA-694-12), Dayton, OH.

Gallo, J.J., and Paveza, G.J. (2006). Activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living assessment. In J.J. Gallo, T. Fulmer, and G.J. Paveza (Eds.), Handbook of geriatric assessment (4th ed., pp. 193-240). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Gawande, A. (2009). A challenge for practitioners worldwide: Why safe surgery saves lives. Journal of Perioperative Practice, 19(10), 312.

Gruber, T. (1993). A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowledge Acquisition, 5, 199.

Hoey, J., Poupart, P., von Bertoldi, A., et al. (2010). Automated handwashing assistance for persons with dementia using video and a partially observable markov decision process. Computer Vision and Image Understanding, 114, 503-519.

Kane, R., Preister, R., and Totten, A.M. (2005). Meeting the challenge of chronic illness. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Katz, S. (1983). Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility and instrumental activities of daily living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 31(12), 721-726.

Katz, S., Down, T.D., Cash, H.R., and Grotz, R.C (1970). Progress in the development of the index of ADL. The Gerontologist, 10(1), 20-30.

Lane, R., Stanton, N.A., and Harrison, D. (2006). Applying hierarchical task analysis to medication administration errors. Applied Ergonomics, 37(5), 669-679.

Lawton, M.P., and Brody, E.M. (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9(3), 179-186.

Levine, C., Halper, D., Peist, A., et al. (2010). Bridging troubled waters: Family caregivers, transitions, and long-term care. Health Affairs, 29(1), 116-124.

Lippa, K.D., Klein, H.A., and Shalin, V.L. (2008). Everyday expertise: Cognitive demands in diabetes self-management. Human Factors, 50(1), 112-120.

Mihailidis, A., Boger, J.N., Craig, T., and Hoey, J. (2008). The coach prompting system to assist older adults with dementia through handwashing: An efficacy study. BMC Geriatrics, 8, 28.

Mukamel, D.B., Peterson, D.R., Temkin-Greener, H., et al. (2007). Program characteristics and enrollees’ outcomes in the program for all-inclusive care for the elderly (PACE). Milbank Quarterly, 85(3), 499-531.

Murphy, S.L., Gretebeck, K.A., and Alexander, N.B. (2007). The bath environment, the bathing task, and the older adult: A review and future directions for bathing disability research. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(14), 1067-1075.

Novak, J.D. (1990). Concept maps and vee diagrams: Two metacognitive tools for science and mathematics education. Instructional Science, 19, 29-52.

Osterberg, L., and Blaschke T. (2005). Adherence to medication. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(5), 487-497.

Rogers, W.A., Mykityshyn, A.L., Campbell, R.H., and Fisk, A.D. (2001). Analysis of a “simple” medical device. Ergonomics in Design: The Quarterly of Human Factors Applications, 9(1), 6-14.

Shepherd, A. (2001). Hierarchical task anlysis. London: CRC Press.

Siegel, J.D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., and Chiarello, L. (2007). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Stanton, N. A. (2006). Hierarchical task analysis: Developments, applications, and extensions. Applied Ergonomics, 37, 55-79.

Stilley, C.S., Bender, C.M., Dunbar-Jacob, J., Sereika, S. and Ryan, C.M. (2010). The impact of cognitive function on medication management. Health Psychology, 29(1), 50-55.

Strong, S., Rigby, P., Stewart, D., et al. (1999). Application of the person-environment-occupation model: A practical tool. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(3), 122-133.

The Staff of the Benjamin Rose Hospital. (1959). Multidisciplinary studies of illness in aged persons. II. A new classification of functional status in activities of daily living. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 9(1), 55-62.

Wilkins, V.M., Bruce, M.L., and Sirey, J.A. (2009). Caregiving tasks and training interest of family caregivers of medically ill homebound older adults. Journal of Aging & Health, 21(3), 528-542.

Wolf, L., Potter P., Sledge J.A., et al. (2006). Describing nurses’ work: Combining quantitative and qualitative analysis. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 48, 5-14.

Zayas-Cabán, T., and Brennan, P.F. (2007). Human factors in home care. In P. Carayon (Ed.), Handbook of human factors and ergonomics in health care and patient safety. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.