Chapters 2 and 3 outlined the history of medical-device regulation in the United States and the components of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) medical-device regulatory infrastructure, including the 510(k) clearance process. This chapter discusses the 510(k) process in more detail. It explains how the FDA has implemented its regulatory authorities1 and discusses the challenges faced by the FDA and others affected by the program.

The 510(k) submission is the most common premarket regulatory submission received by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) within the FDA. It applies to device types that are generally considered to pose moderate risk and that are not exempt from premarket review but not to high-risk device types that are subject to premarket approval (PMA). The Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that in 2003–2007, 31% (15,472) of all devices entered the market through the 510(k) pathway, 1% through PMA, and 1% through programs such as the humanitarian device exemption. The remaining 67% of device types were exempt from premarket review (Class I devices made up 95% and Class II devices 5% of these) (GAO, 2009c).2 A study of 510(k) submissions from 1996 to 2009 found that more than 80% of 510(k)-cleared devices were classified as Class II, about 10% Class I, and less than 2% Class III devices (IOM,

___________________

1In this report, the phrase regulatory authority refers to the power that the legislature gives the FDA to enforce statutes.

2Data are for the 50,189 devices listed with the FDA by device manufacturers during the period October 1, 2002, through September 30, 2007 (GAO, 2009c).

2011). About 90% of 510(k) submissions for Class I and Class II devices are cleared by the FDA to enter the market (GAO, 2009c).

A number of situations require a manufacturer to submit a 510(k) submission. By regulation, a new 510(k) notification must be submitted if

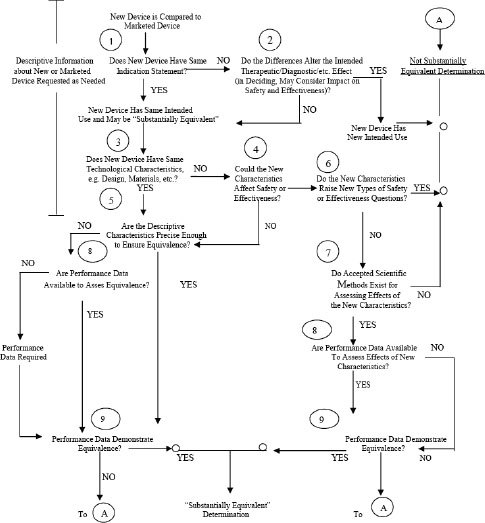

the device is one that the person currently has in commercial distribution or is reintroducing into commercial distribution, but that is about to be significantly changed or modified in design, components, method of manufacture, or intended use. The following constitute significant changes or modifications that require a premarket notification: (i) A change or modification in the device that could significantly affect the safety or effectiveness of the device, e.g., a significant change or modification in design, material, chemical composition, energy source, or manufacturing process; (ii) A major change or modification in the intended use of the device3 [see Figure 4-1].

Although they are not specified in the 510(k) regulation, there are generally four categories of parties who must submit a 510(k) submission to the FDA (FDA, 2010f):

1. Domestic manufacturers introducing a device into the US market.

2. Specification developers introducing a device into the US market.

3. Repackagers or relabelers who have made labeling changes or whose operations substantially affect the device.

4. Foreign manufacturers or exporters or US representatives of foreign manufacturers or exporters introducing a device into the US market.

The 510(k) clearance mechanism rests on the notion of “substantial equivalence.” A device must be found to be substantially equivalent to a predicate device if it is to be cleared through the 510(k) process for commercial distribution. To be considered substantially equivalent, devices must meet criteria that are detailed in Figure 4-1.

Congress has mandated that the FDA give priority review to PMA applications that have innovative or breakthrough technology.4 There is no legal framework for the FDA to request or consider whether a 510(k)-eligible device is innovative with the review process.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE 510(K) PROCESS

The Medical Device Amendments of 1976 provided that all postamendment devices were automatically to be classified into Class III—that is, as high risk—with specific exceptions.5 The primary exception involved

___________________

321 CFR § 807.81 (a)(3).

4FFDCA § 515(d)(5); 21 USC § 360e(d)(5) (2006).

5FFDCA § 513(f)(1), 21 USC § 360c(f)(1) (2006).

a postamendment device that was “substantially equivalent” to a “type of device” that either was a preamendment device that had not been classified or was not a preamendment device but had already been classified into Class I or Class II.6 Another exception provided that a postamendment device would not be in Class III if the FDA, in response to a petition, classified it into Class I or Class II.7 The ultimate intention was that even postamendment devices would be classified, on the basis of risk, into the appropriate category. Until then, any new product proposed for marketing after 1976 would be subject to PMA requirements unless it were substantially equivalent to a preamendment device already in Class I or Class II (or not yet classified) or reclassified by the FDA down from Class III. This structure would place enormous resource demands on the agency as technology evolved and newer devices were developed. The agency would either have to process increasing numbers of PMAs or have to go through a reclassification process that was procedurally cumbersome, labor-intensive, and time-consuming.

Instead, the FDA permitted the manufacturer of a postamendment device to demonstrate “substantial equivalence” to a preamendment device in Class I or II as part of the 510(k) submission.

Substantial Equivalence

As detailed in Appendix A, the FDA adopted a broad reading of the term substantial equivalence and used the 510(k) pathway to avoid requiring PMAs for (or down-classifying) many new and novel devices that would have been placed in Class III (Hutt et al., 2007, supra note 11, 986).8,9,10,11,12 Congress had not defined substantial equivalence in the 1976 law. The FDA’s liberal interpretation permitted the agency to clear

___________________

6FFDCA § 513(f)(1)(A), 21 USC § 360c(f)(1)(A) (2006).

7FFDCA § 513(f)(1)(B), 21 USC § 360c(f)(1)(B) (2006).

8Memorandum Re: Medical Device Hearing, May 4, 1987, Medical Devices and Drug Issues: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t of the H. Comm. on Energy and Commerce, 100th Cong. 345 (1987) (referred to in the statement of Rep. Henry A. Waxman, Chairman, H. Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t).

9Food and Drug Administration Oversight: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t of the H. Comm. on Energy and Commerce, 102d Cong., pt. 2, at 1 (1992).

10Memorandum Re: Medical Device Hearing, May 4, 1987, Medical Devices and Drug Issues: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t of the H. Comm. on Energy and Commerce, 100th Cong. 337 (1987) (referred to in the statement of Rep. Henry A. Waxman, Chairman, H. Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t).

11Medical Devices and Drug Issues: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t of the H. Comm. on Energy and Commerce, 100th Cong., 384 (1987) (statement of James S. Benson, Deputy Director, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services).

12Guidance on the CDRH Premarket Notification Review Program (K86-3) (June 30, 1986) available at http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm081383.htm.

most postamendment devices as substantially equivalent to preamendment devices or even to a postamendment device previously cleared through the 510(k) process (a process known as piggybacking one device onto a series of precedents). By 1989, the agency was concerned that an adverse court ruling on this approach would cripple the 510(k) clearance process and force many new devices into the PMA system. The FDA sought13 and in 1990 obtained congressional ratification of its interpretation when the following language was added to the statute:

A. For purposes of determinations of substantial equivalence … the term “substantially equivalent” or “substantial equivalence” means, with respect to a device being compared to a predicate device, that the device has the same intended use as the predicate device and that [the FDA] by order has found that the device –

(i) has the same technological characteristics as the predicate device, or

(ii)(I) has different technological characteristics and the information submitted that the device is substantially equivalent to the predicate device contains information, including clinical data if deemed necessary by [the FDA], that demonstrates that the device is as safe and effective as a legally marketed device and (II) does not raise different questions of safety and efficacy than the predicate device.

B. For purposes of subparagraph (A), the term “different technological characteristics” means, with respect to a device being compared to a predicate device, that there is a significant change in the materials, design, energy source, or other features of the device from those of the predicate device.14

Congress did not define predicate device but prohibited the use as a predicate of any device removed from the market by the FDA or found by a court to have been adulterated or misbranded.15 As mentioned in Chapter 3, the FDA has not used these authorities widely.

The change provided legal support for the FDA’s policy of piggybacking various 510(k) submissions in a string of decisions, so a new product could rely on any lawfully marketed device as a predicate and substantial equivalence to a preamendment device did not have to be established. Also, by being permitted to show that its product was “as safe and effective as” a predicate (instead of merely having substantially equivalent safety and effectiveness), a 510(k) submitter could improve the safety and effectiveness of its device without triggering the risk of being found not substantially

___________________

13Medical Device Safety: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t of the H. Comm. on Energy and Commerce, 101st Cong. 172 (1989–1990) (statement of James S. Benson, Acting Commissioner, Food and Drug Administration).

14FFDCA § 513(i)(1), 21 USC § 360c(i)(1) (added by SMDA § 12, 104 Stat. at 4523).

15FFDCA § 513(i)(2), 21 USC § 360c(i)(2) (added by SMDA § 12, 104 Stat. at 4523).

equivalent and having to undergo a PMA review. Thus, a new device might be superior to its predicate and still be substantially equivalent to it. “In this way, the standard for safety and effectiveness in a determination of substantial equivalence will evolve slowly as the prevailing level on the market changes, rather than being tied solely to comparison with a pre1976 device.”16 In contrast, the change did not require reliance on the best predicate device, so a product that was truly inferior to the current state of the art could still enter the market if the manufacturer could identify any predicate that had not been removed from the market and to which it was substantially equivalent. Once a device is cleared through the 510(k) process and becomes eligible as a predicate, it cannot be removed from the pool of available predicates unless it has been banned or declared adulterated or misbranded and pulled from the market. The FDA estimates that 29% of the devices that have been cleared either were never marketed or were marketed but are no longer available (FDA, 2010b). Whether that reflects deficiencies in product safety or effectiveness, cost, utility, or competitiveness is not known. Nevertheless, the discontinued (or never launched) products may all serve as predicates for future devices. The FDA is unable to dictate which predicates can be selected for 510(k) decision-making. In some cases, the FDA has published guidance documents advising manufacturers on how to demonstrate the predicate relationship. These guidance documents are nonbinding on the manufacturer or the agency.

Devices are constantly updated with minor changes throughout their life cycle for a variety of reasons. The FDA has issued guidance on device modifications and on when a new 510(k) submission is required (FDA, 1997).17 This guidance does not require manufacturers to report all minor changes or series of minor changes to the agency. The decision of when there has been a significant enough change or series of changes to trigger a new 510(k) submission is largely at the discretion of the manufacturer. Incremental design changes are difficult to define and if poorly controlled can lead to device “creep,” in which there is the potential for a marketed device to differ significantly from a device cleared through the 510(k) review.

Predicates

Identifying an appropriate predicate is a central component of the 510(k) process. The FDA maintains databases that are used to identify predicate devices from a catalog of previously cleared devices. Classifications can be found by searching the Product Code Classification Database. Products are cataloged by using both classification symbols and product-

___________________

16H.R. Rep. No. 101-808, at 25.

17Updated guidance was issued by the FDA on July 27, 2011, after the committee had completed its work.

code symbols, known as procodes. Procodes are unique three-letter product identifiers assigned by the FDA to all products (whether classified or not). The databases can be searched by product name, manufacturer, whether the device is a preamendment or postamendment device, or procode (FDA, 2009c).

The critical process of identifying predicates is hampered by problems with data systems and information-sharing within CDRH. The Product Code Classification Database is subject to nuances in spelling, formatting, and errors in entries and is unwieldy and difficult to use.18 In addition, the application of procodes by the FDA has been inconsistent, and there is no user-friendly glossary of this information. Those technical issues often make it difficult to track cleared products (FDA, 2010c).

More detailed information on predicate devices can be obtained through a 510(k) summary or a 510(k) statement. A 510(k) summary or 510(k) statement is required for all 510(k) submissions (FDA, 2010e). The 510(k) summary must provide sufficient detail to understand the basis for a determination of substantial equivalence (FDA, 2010e). In lieu of a 510(k) summary, the manufacturer can opt for a 510(k) statement. The 510(k) statement is a certification that the manufacturer will provide information supporting the FDA finding of substantial equivalence to any person within 30 days of a written request (FDA, 2010e). The Office of In Vitro Diagnostics posts a decision summary on line for devices that it clears through the 510(k) program. The Office of Device Evaluation (ODE) does not post decision summaries on line (FDA, 2010h).

The FDA has acknowledged that information provided to manufacturers for the purpose of identifying predicates is often limited, that 510(k) summaries often lack critical details that might be of value to companies, and that the procode process used in the databases is not transparent (FDA, 2010b). Medical-device manufacturers, in general, agreed with that assessment and suggested that the agency eliminate the 510(k) statement and require a standardized summary and a better method of categorizing products to allow identification of predicate devices (FDA, 2010d).19 The FDA has proposed posting on line a verified 510(k) summary, photographs and schematics of the device to the extent that they do not contain proprietary information, and information showing how cleared 510(k) devices are re-

___________________

18For example, Letter from the Medical Imaging and Technology Alliance to FDA, Docket Number FDA-2010-N-0054-0055 (March 19, 2010); Letter from AdvaMed to FDA Docket Number FDA-2010-N-0054-0058.1 (March 19, 2010); Comments from James W. Lewis, Salus Ventures, LLC to FDA, Docket Number FDA-2010-N-0054-0015.1 (March 8, 2010).

19For example, Presentation by R. Glenn Neuman, New World Regulatory Solutions, Docket Number FDA-2010-N-0054-0010.1 (February 18, 2010); Comments by Charmaine Sutton, The Tamarack Group, Docket Number FDA-2010-N-0054-0014.1 (March 6, 2010); Comments by Beth Johnson, Medline Industries Inc., Docket Number FDA-2010-N-0054-0016.1 (no date given).

lated to each other and identifying the premarket submission that provided the original data on or validation of a particular product type. This proposal has raised concerns in industry about the protection of proprietary information (FDA, 2010b, 2010c, 2011a).

Once an appropriate predicate has been identified, the objective of the 510(k) submission is to demonstrate that the new device under review is substantially equivalent to the predicate(s). If it is determined that the device under review has different technologic characteristics from the predicate(s), the FDA may request additional information to evaluate whether the new device is as safe and as effective as the predicate. As mentioned in Chapter 2, about 15% of Class II and Class III 510(k) submissions in FY 2005–2007 had new technologic characteristics (GAO, 2009b).

The FDA, in an internal review of its 510(k) program, noted the difficulty of making comparisons when new issues of safety and effectiveness have been identified; industry representatives, in public comments, noted a lack of predictability in whether the agency would consider a design or material change important enough to constitute a technologic change that would affect the substantial-equivalence justification. The FDA and industry both noted a lack of consistency in the core evidence being requested by the agency for equivalence decisions; industry suggested that this was a process problem (FDA, 2010b, 2010d).

Over the history of the program, systems for tracking and linking 510(k) decisions and predicates have been insufficient (see Chapter 3). As a result, it would be difficult for anyone to trace back the chain of predicates leading to the preamendment device in connection with a device currently on the market. Given that circumstance, the committee finds it important to note that a fundamental difference exists between the 510(k) and PMA pathways. In reviewing a PMA, the FDA must ask, Is this device reasonably safe and effective for its intended use? The 510(k) review asks, Is this device substantially equivalent to some other device whose safety and effectiveness may never have been assessed?

Finding 4-1 The 510(k) process determines only the substantial equivalence of a new device to a previously cleared device, not the new device’s safety and effectiveness or whether it is innovative. Substantial equivalence, in the case of a new device with technologic changes, means that the new device is as safe and effective as its predicate.

Finding 4-2 Current 510(k) decisions have been built on a chain of predicates dating back to devices on the market in 1976. Because data systems in the FDA are inadequate, the agency does not have the ability to trace the supporting decisions.

Pushing the Limits of Predicates

As technology moves forward and more sophisticated devices are developed, the threshold of how predicates can be used in the 510(k) review is expanded and broadened. For the most part, manufacturers prefer to use the 510(k) process rather than the PMA process even for more complex devices because of the burden presented by the PMA process. The incentives for manufacturers to seek entry into the market through the 510(k) process rather than the PMA process are discussed in Chapter 3.

The FDA has cited the practice of multiple and “split” predicates as important challenges in the 510(k) review process (FDA, 2010b). 510(k) submissions that use split predicates combine two or more predicates: one or more predicates for claiming intended use and one or more for claiming technologic characteristics. Split predicates have been used for a variety of devices, including devices with incremental changes. 510(k) submissions that use multiple predicates combine functions of more than one predicate device. The FDA’s concern about multiple and split predicates in device submissions stems from an internal analysis that showed a greater mean rate of adverse-event reports related to devices whose 510(k) submissions cited more than five predicates (FDA, 2010b).

CDRH’s internal working group recommended further analysis of multiple predicates and issuance of clarifying guidance on the use of multiple and split predicates in an effort to improve transparency and reproducibility of the review process. The center has not proposed stopping the use of multiple predicates (FDA, 2011a). CDRH proposed elimination of or restriction in the use of split predicates. However, industry groups voiced concerns that eliminating or limiting the use of split predicates may have a chilling effect on innovation (FDA, 2011a).20

Key Regulatory Terms

The determinations of “intended use” and “indications for use” are critical elements in the 510(k) process because they directly affect the determination of substantial equivalence (see Figure 4-1). To continue through the 510(k) process, a new device must have the same intended use as its predicate. However, a device is not required to have the same indications for use as the predicate (FDA, 2010b). A 510(k) submission may include new or different indications for use as long as they do not affect the safety and effectiveness of the device by having different intended therapeutic, diagnostic, prosthetic, or surgical uses from the predicate. It is important

___________________

20In January 2011, CDRH announced that it no longer intends to use the term split predicate. It plans to issue guidance to clarify the circumstances under which it is appropriate to use multiple predicates to demonstrate substantial equivalence (FDA, 2011a).

FIGURE 4-1 The FDA substantial-equivalence decision tree.

SOURCE: FDA, 2009a.

to note that terms intended use and indications for use were developed for other regulatory purposes but have been adapted by CDRH to be used as part of the substantial-equivalence decision-making process of the 510(k) review (FDA, 1997).

As stated above, intended use is one of the legal standards that the FDA is required to adhere to in making a determination about substantial equivalence. The definition of a device in the statute twice uses the standard of something that is “intended for use” in disease or in affecting body struc-

ture or function.21 The safety and effectiveness of a device are judged with respect to persons for whose use the device is intended and with respect to the conditions of use suggested in the labeling.22

The FDA’s regulations state that the intended uses of a device are “objectively” determined based on the persons legally responsible for the labeling of the device by written or verbal statements of those persons (for example, in product labels and labeling, marketing materials, or in reports to investors) or the circumstances surrounding the distribution of the device.23 The uses that a seller intends for its product thus govern whether the agency has jurisdiction over the product and whether the product is a device, drug, or biologic.

The phrase indication for use is not found in the statute. It is adapted from the regulations for the PMA process,24 which are in turn patterned on the prescription-drug approval process.25 The phrase is a key part of the essential directions to a healthcare practitioner on using the product safely and effectively. For prescription-drug approvals, the FDA created a standard format for labeling, which includes an “indications for use” section that describes the purpose of the drug in relation to a disease or condition (such as to diagnose, prevent, or treat for a named disease or a manifestation of the disease).26 The full prescribing information in the labeling must also contain sufficient details to provide for the safe and effective use of the drug, including such information as dosage forms, dose ranges, routes of administration, duration of use, contraindications, and precautions. In the FDA’s view, approved labeling content was “authoritative,” not “definitive.” For medical devices, “indications for use” provides a description of the patient population and disease or condition that the device will diagnose, treat for, prevent, cure, or mitigate.27 The indications for use are meant to represent a relatively precise description of the clinical applications of the device. Indications for use may be derived from clinical studies, may originate from the history of the predicate-device use, or may be defined by the manufacturer.

A difference between intended use and indications for use from a regulatory perspective is that indications for use are contained in the product labeling provided by the seller, whereas intended use may also be found in other marketing materials and activities of the seller. A 510(k) submission does not have to contain the full final labeling. However, the submission does include proposed labels, labeling, and advertisements, which should

___________________

21FFDCA § 201(h) (2), (3).

22FFDCA § 513(a) (2) (A), (B).

2321 CFR § 801.4.

2421 CFR § 814.20(b)(3)(i).

2521 CFR § 201.57.

2621 CFR § 201.5 7(c)(2).

2721 CFR § 814.20(b)(3)(i).

be in sufficient detail to describe the device, its intended use, and the directions for its use.28 510(k) submissions have only to include a statement of the submitter’s intended use of the device.

The distinction between intended use and indications for use is further complicated by the difficulty of clearly differentiating a medical device’s general “tool” use and its therapeutic or clinical applications (FDA, 2010b). Devices may span the spectrum of tool and clinical applications:

• A device that has a well-established general intended use as a tool but does not have specific clinical indications for use, such as medical imaging platforms and general surgical devices (for example, suture material, clamps, and retractors).

• A device that has well-established general intended use as a tool and has been expanded to include one or more specific clinical indications for use (such as a surgical laser that evolves to be used specifically for the removal of tattoos or an ablation device that has a general tool use of destruction of soft tissue and has evolved to be used for treatment for specific types of cancer).

• A device that would not be considered a general tool and has only a specific clinical intended use and indication for use, such as a joint replacement.

Determining the intended use and indications for use of medical devices at either end of the foregoing spectrum is relatively straightforward. Problems can arise, however, with devices that fall in the center of the spectrum, that is, general tools that are evolving into devices that have explicit and specific uses that are no longer consistent with use as a general tool.

Device types that are general tools can often be used for multiple clinical purposes, in multiple clinical disorders, and in multiple anatomic locations. In the 510(k) process, it is possible that those types of devices could be required to provide evidence to support the clinical utility of every possible indication, disease state, and anatomic location for the device even if the intended use has not changed. For many devices, that could be an onerous and unreasonable burden.

Some devices, however, evolve so that new versions can be used only for specific clinical indications, such as an ablation device that evolves to be used only for tattoo removal. Given the structure of the 510(k) process (see Figure 4-1), these devices, which are used only for specific clinical indications, may still be able to cite a predicate with a general tool intended use. Manufacturers may not, however, promote an indication for use that is not cleared by the FDA through a 510(k) submission or approved as part

___________________

2821 CFR § 807.87(e).

of a PMA. Thus, there is a tension between a manufacturer’s desire to get through the 510(k) process as easily and quickly as possible and its commercial desire to advertise the device for particular indications.

GAO noted that about 1% of 5,063 Class II and III submissions reviewed by the FDA in 2005–2007 had a new intended use (GAO, 2009b). Slightly more than 12%, however, had a different indication for use from the predicate, of which more than 99% were found not to have affected the intended use. Of the 510(k) submissions that were found to be substantially equivalent, almost all had the same intended use, whereas more than half the submissions found not to be substantially equivalent had a new intended use (GAO, 2009b). In light of the increasing complexity and diversity of devices that fall within the 510(k) process, it is important to consider the clarity of the key terms in these initial steps that are pivotal in the 510(k) decision-making process. For instance, early recognition of a potential change in intended use can permit CDRH to determine the need for, and thus obtain, appropriate types of expertise and experience for the review; belated recognition may prevent summoning of the necessary human resources.

CDRH’s Preliminary Internal Evaluations—Volume 1: 510(k) Working Group Preliminary Report and Recommendations found that fluid and ill-defined regulatory terms create confusion and inconsistency in the center and for industry (FDA, 2010b). In particular, CDRH cited concerns about use of such terms as intended use and indications for use. Given the subjective judgment needed to determine the criteria for evaluating whether a different indication for use may constitute a new intended use, CDRH has stated that it is difficult to ensure consistent decision-making (FDA, 2010b). The difficulty in addressing the influence of indications for use on a device’s intended use is exacerbated by the variation in how intended use and indications for use are used in different guidance documents; in some cases, these terms are used synonymously (FDA, 2010b). Industry has also pointed to the varying interpretations of intended use and indications for use as an important source of unpredictability in the 510(k) process (FDA, 2010d). As a result, CDRH has proposed the consolidation of the two terms into a single term, intended use (FDA, 2010b).

Finding 4-3 The key regulatory terms intended use and indications for use are poorly defined and are susceptible to varying interpretations that lead to inconsistency in decision-making and create confusion among FDA staff, industry, Congress, the courts, and consumers.

Finding 4-4 The 510(k) clearance process does not consistently recognize distinctions among devices cleared solely as tools, those cleared for specific clinical applications, and general tools that also have specific clinical applications.

Off-Label Use and Its Effect on the 510(k) Clearance Process

The practice of off-label use is encountered with all types of medical products, and the problems that it presents are not peculiar to medical devices or to 510(k)-cleared medical devices. The committee did not consider it within the scope of this study to undertake a detailed analysis of the practice of off-label use, but it did review how the off-label use of medical devices affects the 510(k) process. The term off-label use is not found in the statute, nor has the FDA ever issued a definitive interpretation of it. The committee defined, for its discussion, off-label use of a 510(k)-cleared medical device to be any use of the device that is not included in the cleared indications for use (if any) or in its statement of intended use.

It is generally argued that off-label uses of medical products may offer clinical benefits as well as potential risks. A physician’s perspective on off-label use is focused on concerns different from the FDA’s and may include issues of improving patient care, professional ethics, the development of research, malpractice, and insurance reimbursement. Rarely does FDA regulation impinge a physician’s freedom to use a device as he or she deems appropriate in the scope of medical practice.29 The scope of the FDA’s power to regulate medical practice, traditionally a matter of state regulation, has been a sensitive issue dating back to the legislative debate about passage of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act in 1938.30 Then and when passing the 1962 Drug Amendments, Congress disclaimed an intent of the FDA’s regulation of medical products to entail broad regulation of medical practice.31,32 However, courts have never found constitutional limits on the FDA’s power to regulate physicians,33 and most legal scholars agree that “there is little doubt under modern law that Congress has ample power to regulate the manufacture, distribution, and use of drugs and medical devices.”34 The 1976 Medical Device Amendments expressly authorized the FDA to approve medical devices subject to restrictions on their use and

___________________

2921 USC § 396

30See Joel E. Hoffman, Administrative Procedures of the Food and Drug Administration, in 2 Fundamentals of Law and Regulation: An In-Depth Look at Therapeutic Products 12, 17-24 (David G. Adams et al. eds., 1999) [hereinafter Fundamentals of Law and Regulation].

31S. REP. No. 87-1744 (1962), reprinted in 1962 USCC.A.N. 2884, 2820-21.

32Legal Status of Approved Labeling of Prescription Drugs; Prescribing for Uses Unapproved by the Food and Drug Administration, 37 Fed. Reg. 16,503 (Aug. 15, 1972) (discussing, in the preamble to a proposed rulemaking, Congress’s legislative intent in passing the FFDCA).

33David G. Adams, The Food and Drug Administration’s Regulation of Health Care Professionals, in 2 Fundamentals of Law and Regulation, supra note 29, at 424-25.

34Richard A. Epstein, Why the FDA Must Preempt Tort Litigation: A Critique of Chevron Deference and a Response to Richard Nagareda, 1 J. TORT L. art. 5, at 7 (2006), http://www.bepress.com/jtl/vol1/iss1/art5Epstein.

distribution,35 showing congressional recognition that the safety of a device may depend as much on how it is used in a clinic setting as on the process through which it is cleared or approved. The Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy provisions of the 2007 Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act reflect a similar view for drugs. Still, as a policy matter, the FDA has generally sought to avoid potential involvement in regulation of medical practice. As discussed in Chapter 3, the FDA has not made substantial use of its statutory authorities to restrict use and distribution of medical devices.

Device makers and sellers, in contrast, are subject to FDA regulation of the marketing, labeling, and promotion of medical devices. Devices may be promoted and advertised only for the uses that the FDA has approved or cleared. The agency does allow the dissemination of scientific information on unapproved or uncleared uses of medical devices in some circumstances as an educational, not promotional, activity. Examples of dissemination activities that are allowed include continuing medical education programs and research published in peer-reviewed scientific and medical journals (FDA, 1998). The potential for off-label use—perhaps facilitated by promotional activities of the manufacturer, perhaps driven solely by medical practice—creates a specific problem for the 510(k) process. This problem is related to the FDA’s determination of the intended use and indications for use of a submission. Intended use in a 510(k) submission is reviewed solely on the basis of the proposed labeling. The FDA has the authority to add warnings to the device label for some off-label uses within the 510(k) review, but the agency cannot refuse to clear a device.36 The agency is thus limited in the extent to which it can prevent unsafe or ineffective clinical applications of a proposed device even when these applications are foreseeable and reasonably predictable.

Some devices have multiple potential indications for use. The magnitude of risk associated with some indications for use may be consistent with clearance through the 510(k) process. Others, however, present a greater risk that is more consistent with the requirements of the PMA process. Because of the considerable differences in the burden between 510(k) clearance and the PMA process, including the submission user-fee, data-collection requirements, and time, there is a potential for manufacturers to circumvent PMA of a device for the higher-risk indications and instead seek a 510(k) clearance in connection with the lower-risk indications. CDRH has indicated that the practice of omitting higher-risk indications from the proposed labeling of 510(k) submissions to avoid a more intensive PMA review is an area of concern. CDRH cited examples in which there has been reasonable

___________________

35Medical Device Amendments of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-295, § 2, 90 Stat. 539, 565 (adding Section 520(e) of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act) (codified as amended at 21 USC § 360j(e) (2006)).

36FFDCA § 513(i)(l)(E).

BOX 4-1

Case Study: Biliary Stents in Peripheral Vasculature

There are small stents whose size makes them suitable for application both in bile ducts and in peripheral vasculature. Because the former indication involves using a product in patients who have advanced cancer and short life expectancies, the long-term durability of the product is not critical with a biliary stent, and the FDA allows biliary stents to be cleared via the 510(k) process. The same stent, if used in peripheral vasculature, would require PMA because long-term risks posed by the device are of greater concern in this patient population. As a result of having multiple premarket-review pathways—510(k) and PMA—available for a single device, it was possible for manufacturers to circumvent the PMA process for stents used in peripheral vasculature by clearing them through the 510(k) process and then having them be used off-label in peripheral vasculature. It was estimated that up to 90% of biliary-stent use was for off-label application in treating peripheral vascular disease (Bridges and Maisel, 2008).

evidence that the intended use documented in a 510(k) submission differs greatly from how the device will be used once it is cleared (FDA, 2010b); see Box 4-1 for a case study of biliary stents. To address that concern, CDRH has proposed seeking authority to consider an off-label use in determining the intended use of a device under 510(k) review (FDA, 2011a).

The FDA can take various steps to address off-label use that is the result of marketing practices of the sellers. If the off-label use, however, is the result of spontaneous medical practice, its authority over marketing is of no use. Furthermore, given the limited and problematic postmarketing surveillance of devices in general, accurately identifying adverse events or developing an evidence base on innovative indications for devices is not currently feasible. These factors complicate the FDA’s ability to determine whether the potential off-label use of a device raises new types of questions about safety and effectiveness.

In general, the committee noted that there is a lack of data on off-label uses of 510(k)-cleared devices; in the absence of data, there is no basis for concluding whether such uses are, on balance, beneficial or harmful to the public.

Finding 4-5 There are no reliable tools for collecting data on the clinical use of and health outcomes related to devices cleared by

510(k) so that such data could become available for regulatory, healthcare policy, and medical decision-making purposes.

Finding 4-6 Insufficiency of information about how devices are used and perform once they are on the market adversely affects the ability of the FDA to evaluate devices’ intended uses, indications for use, and substantial equivalence in a 510(k) review.

Class III Devices Remaining in the 510(k) Program

In the 1976 legislation, Congress directed that all preamendment devices classified in Class III undergo the PMA process on a timetable to be set by the FDA but could remain on the market pending completion of the review.37 During the review period, new (postamendment) products of the same types as preamendment Class III devices would be permitted to enter the marketplace, essentially on the same terms as the preamendment devices.38 Thus, the manufacturer of a postamendment device would not have to submit and obtain approval of a PMA before the manufacturers of a preamendment were required to. Instead, the manufacturer would submit a 510(k) notification demonstrating that its proposed product was “substantially equivalent” to a Class III preamendment device. Once PMA requirements were imposed, however, the use of the 510(k) process would terminate. It was a transitional tool for Class III devices.

The FDA has not completed the task given to it in 1976 to bring all devices classified in Class III under PMA review requirements. In the first decade under the 1976 amendments, over 80% of postamendment Class III devices entered the market on the basis of 510(k) submissions showing substantial equivalence to preamendment devices.39 Congress has directed the FDA several times to finish the transition (FDA, 2011b).40 Although the FDA has done so for many Class III device types, there are still 25 device types that remain eligible to enter the market through the 510(k) process. In 2009, the FDA implemented a five-step process called the 515 Program Initiative with the aim of completing the task (FDA, 2011b). As of April 2011, the FDA has assessed the risks and benefits associated with 21 device types (step 2 of the process) and has received and reviewed public comments

___________________

37FFDCA § 515(b)(1), 21 USC § 360e(b)(1) (2006).

38FFDCA § 513(f)(4), 21 USC § 360c(f)(4) (2006).

39Memorandum Re: Medical Device Hearing, May 4, 1987, Medical Devices and Drug Issues: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t of the H. Comm. on Energy and Commerce, 100th Cong. 344 (1987) (referred to in the statement of Rep. Henry A. Waxman, Chairman, H. Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t).

40SMDA, Pub. L. No. 101-629, 104 Stat. 4511.

on five device types (step 4 of the process). The agency has issued a final rule for one of the 26 device types (FDA, 2011c; GAO, 2011).

Finding 4-7 A number of Class III devices continue to be cleared through the 510(k) process rather than, as Congress has always intended, through the PMA process.

Types of 510(k) Submission

An applicant may choose from three types of premarket notification or 510(k) submission for marketing clearance, depending on the circumstances. Although there is no standardized 510(k) submission form, the FDA has a guidance document advising manufacturers on the format of submissions (FDA, 2005).

In addition to the traditional 510(k) submission, the FDA developed two submission types to streamline premarket notification. The special 510(k) submission uses components of the quality system regulations (QSRs) to address important modifications in a product already on the market that warranted a new 510(k) submission. The abbreviated 510(k) submission, as its name implies, is focused on reducing the length and complexity of a submission by allowing an applicant to show that its product conforms with agency guidance documents, special controls, or recognized performance standards as a means of showing substantial equivalence (FDA, 2010a). The two alternative review processes were developed through guidance rather than rule-making. A review of 510(k) submissions from 1996 to 2009 found that about 80% of submissions were traditional 510(k)s, 16% were special, and 3% were abbreviated (IOM, 2011).

Traditional 510(k) Submission

The traditional 510(k) submission can be used for all 510(k)-eligible devices. Although the FDA does not have a standardized format for submissions, it provides a recommended format in a guidance document (FDA, 2005). The information needed as part of this submission is described in 21 CFR Part 807 Subpart E and includes

• Statement of indications for use.

• 510(k) summary or 510(k) statement.

• Truthfulness and accuracy statement.

• Class II summary and certification.

• Financial certification or disclosure statement.

• Declarations of conformity and summary reports (abbreviated 510(k)s).

• Device description.

• Substantial-equivalence discussion.

• Proposed labeling.

• Sterilization or shelf life.

• Biocompatibility.

• Software.

• Electromagnetic compatibility or electric safety.

• Performance testing—bench, animal, and clinical.

• Information on the standards used and a statement that the submission conforms with them.

• Kit certification.

The first step in preparing any 510(k) submission is identification of a predicate device. As discussed above, it is possible to claim equivalence by using more than one predicate (FDA, 2010a). The demonstration of substantial equivalence is usually based on the information generated by performance testing. Given the wide array of products included in the 510(k) review program, there is a great deal of variation in the types of data that would be required.

The second step in preparing any 510(k) submission is identification of appropriate FDA guidance documents. Although guidance is not binding, it is likely to represent the FDA’s thinking about the product type and to signal the kinds of questions that are likely to be asked by the review staff. In addition to device-specific guidance, the FDA has developed guidance on some cross-cutting device issues including biocompatibility, device software, and electromagnetic compatibility. Ideally, guidances provide submitters advance knowledge of the agency’s concerns, allowing a submitter to anticipate likely questions and to provide appropriate evidence in the initial submission. A goal is to decrease the likelihood of requests from the agency for additional information.

Abbreviated 510(k) Submission

The abbreviated 510(k) submission is used only where device-specific guidance documents are applicable. Those documents communicate regulatory and scientific expectations both to FDA review staff and to industry. They identify the standards or guideposts that must be met for market clearance and provide methods for gathering and presenting such information. The use of the abbreviated 510(k) submission is based on the premise that if a well-recognized method for obtaining data relevant to the 510(k) decision-making process can be identified, the sponsor of a submission can comply with that method and give the FDA a summary report (FDA, 2010a). This submission type should streamline the process, simplify review, and decrease regulatory uncertainty.

All elements described in 21 CFR Section 807.87, as noted above for the traditional 510(k) submission, must still be provided to the FDA, but the use of a standardized method for obtaining these elements and a summarized report should allow more predictable and shorter review timelines. Normally, an abbreviated 510(k) submission would include the same sections as the traditional 510(k) submission. However, because of the important role of conformity with the existing guidance or standard, an abbreviated 510(k) submission should also include a specific section titled “Declarations of Conformity and Summary Reports.” Because a declaration of conformity is based on results of testing, the FDA believes that such a declaration of conformity cannot be submitted until testing according to the guidance or standard has been complete and shown to support substantial equivalence.

Although use of the abbreviated 510(k) submission is intended to simplify and expedite preparation and review, the deadline for agency action on the submission—90 days—remains unchanged.

Special 510(k) Submission

The Safe Medical Device Act of 1990 authorized the FDA to issue regulations requiring preproduction design controls. As a result of that legislative change, the FDA promulgated regulations for Class II and Class III devices and for select Class I devices as part of the good manufacturing practice (or quality system) regulations. The regulations may be described best as a systematic set of requirements and activities for the management of design and development. They include documentation of design inputs, risk analysis, determination of design outputs, test procedures, verification and validation procedures, and documentation of formal design reviews. Manufacturers must ensure that design-input requirements are appropriate so that a device will meet its intended use and the needs of the user population. The manufacturer must establish and maintain procedures for defining and documenting design outputs in terms that ensure conformity with design-input requirements.41

The special 510(k) submission is based on the premise that the rigorous application of design controls in addition to other 510(k) content requirements can be used to substitute for the traditional determination of substantial equivalence of legally marketed devices that are undergoing substantial modification and require new 510(k) submissions (FDA, 2010a). Manufacturers may submit a special 510(k) notification only when they are modifying their own 510(k)-cleared devices. Using this option, a manufacturer will conduct a risk analysis and then report on the verification and

___________________

4121 CFR § 820.30.

validation activities used to demonstrate that the modified device meets the design requirements.

The special 510(k) submission is intended for minor modifications of a device. It is not intended for products that are undergoing modifications of indications for use or labeling changes regarding intended use, for modifications that have the potential to alter the fundamental technology of the device, or for changes in materials that may raise safety or effectiveness issues (for example, use of new materials without a history of use in the same device type).

As an incentive to use this alternative pathway, the FDA seeks to act on a special 510(k) within 30 days of submission. This approach builds on well-established postmarket controls by incorporating them into the premarket review process. The weaknesses of this pathway are that it is limited to products that are undergoing controlled incremental change and has not been systematically analyzed.

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING 510(k) SUBMISSIONS

Data proving substantial equivalence have always been required for 510(k) submissions. However, because there were few special controls, guidances, and recognized standards for the program until 1984, the types and quality of data required were not well defined in its early years.

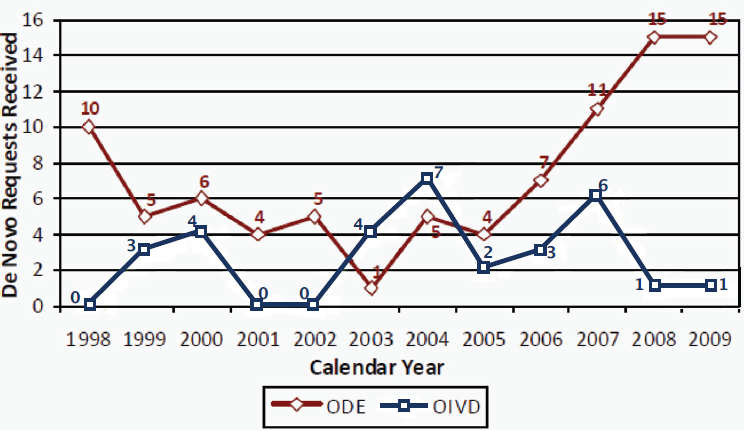

As discussed in Chapter 3, Class II devices may be subject to “special controls.”42 Some of these special controls can be in place either in the premarket period (such as performance standards and FDA guidelines), and others affect the device once it is on the market (such as postmarket surveillance). As of the end of 2010, only 140, or 15%, of all Class II device types were subject to special controls. There are no data on the breakdown of special controls that affect premarket review (Desjardins, 2010). Special controls generally are developed as part of the de novo process.

The primary mechanisms that the FDA has for communicating with manufacturers the evidentiary requirements needed to support a claim of substantial equivalence in 510(k) submissions are guidance documents and standards.

Guidance Documents

The FDA issues guidance documents or guidances on a wide variety of topics, including administrative procedures, such as the processing of submissions, and complex scientific requirements. The following discussion is about guidances focused on the evidence needed to support a substantial-

___________________

42FFDCA § 513(a)(1)(B), 21 USC § 360c(a)(1)(B) (2006).

equivalence claim. Guidance documents can be an important tool in advising manufacturers how to structure their 510(k) submissions to meet the FDA threshold for substantial equivalence. Guidances may also be important in making the review process more predictable and transparent.

There are limitations, however, on how guidances can be developed and used. In some cases, guidance documents include information on technical specifications, minimal engineering descriptions, and bench-level descriptions that would be sufficient to establish substantial equivalence. In other cases, they provide more extensive information on clinical studies that may need to be conducted to demonstrate substantial equivalence. Given the depth of information needed to develop guidance documents, the FDA needs to have sufficient information about the relevant product type to allow it to offer specific advice about how to gather information about a device’s performance to support the submissions’ claims of substantial equivalence.

A guidance document is the product of a long process involving both FDA and non-FDA input. Not all device types fall within the categories for which it is possible for the agency to develop guidance documents. As part of its internal review of the 510(k) program, the FDA reviewed more than 18,000 510(k) submissions and found that 63% lacked device-specific guidance (see Table 4-1) (FDA, 2010b).

Guidance documents “do not create or confer any rights for or on any person and do not operate to bind FDA or the public. An alternative approach may be used if such approach satisfies the requirements of the applicable statute, regulations, or both” (FDA, 2009b). The FDA may choose to use guidance documents over regulations for a number of reasons, including because they are less burdensome to develop than regulations and they can provide a flexible, pragmatic regulatory approach (IOM, 2010).

As discussed in Chapter 3, the development of guidance documents is resource-intensive for the agency. The FDA has indicated that it takes 40 staff years to develop a mandatory performance standard (GAO, 1988). A non-binding guidance document, however, might require less work.

Standards

Standards, like guidance documents, are recommendations and provide specific protocols. Standards are developed by a number of national and international industry and scientific groups. Guidance documents may include references to standards that provide specific instructions for evaluating a particular aspect of a device. Standards become recognized by the FDA through a formal process of review and recognition (FDA, 2007b, 2007c). These recognized standards vary in their content but generally contain information that defines or describes their scope, provides definitions of terminology, lists referenced documents, and provides summaries of test methods, necessary apparatus, protocols, and necessary calculations.

TABLE 4-1 FDA Review Time by Availability of Guidance

| Guidance Available | Mean FDA Days (Mean Total Days) | ≤30 Days, % Completed (Number) | 31–90 Days, % Completed (Number) | 91–365 Days, % Completed (Number) | >365 Days, % Completed (Number) | All, % Completed (Number) |

| Yes | 57.2 (93.0) |

28.7% (1,937) |

65.5% (4,424) |

5.7% (387) |

0.0% (3) |

100% (6,751) |

| No | 65.2 (139.5) |

22.6% (2,617) |

67.2% (7,786) |

10.0% (1,162) |

0.1% (16) |

100% (11,581) |

| All | 62.3 (122.4) |

24.8% (4,554) |

66.6% (12,210) |

8.4% (1,549) |

0.1% (19) |

100% (18,332) |

SOURCE: FDA, 2010b.

Conformity with standards can support a new device’s claim of substantial equivalence to a predicate device. A manufacturer can state its adherence to consensus standards through a Declaration of Conformity to Standards (FDA, 2007a). Conformity with standards is not always a sufficient basis to support a substantial-equivalence finding. Conformity can, however, reduce the amount of documentation that a manufacturer must submit and may also reduce FDA review time.

The FDA and industry have raised concerns about the use of standards in the 510(k) review. The FDA reported inconsistencies in how standards are applied in 510(k) reviews and attributed the problem to insufficient training of review staff and unclear guidance to submitters. A submitter may not be using the most current standard, or may not be documenting use of the standard properly, or may be attempting to use a standard that is not appropriate for the device in question (FDA, 2010b).

Effect of Guidance Documents and Standards on Review Time

Although it is generally believed that use of guidance documents and standards simplifies the regulatory process, it is not clear how much effect they have on premarket review time (see Table 4-1). Devices for which there are guidances generally appear to undergo premarket review more rapidly than other devices. It is possible that the shorter review periods result from other variables in the review process, such as the relative familiarity of both the FDA staff and submitters with the device type, and might not be related to the existence or quality of the guidances themselves. In the absence of a quality-assurance program to rate the quality of submissions and reviews, it is reasonable to speculate but not easy to prove that guidance improves the work done by the sponsor or by the FDA in the 510(k) process.

Use of Clinical Data

The use of clinical data in the regulatory review process is defined by the enabling legislation, the regulations, and the FDA’s implementation of the legislation and regulations. The FDA is able to request clinical data to determine if an indication of use falls within an intended use or if the agency determines that the 510(k) submission under review has new technologic characteristics relative to the predicate(s). The clinical data can be requested by the FDA only if necessary to determine that the new device is as safe and as effective as the predicate device(s). Moreover, the agency may not ask for scientific evidence greater than the “least burdensome” to answer the question.

In practice, clinical data play a very small role in the 510(k) process. The GAO found that in FY 2005–2007 about 15% of Class II and Class

III 510(k) submissions had new technologic characteristics (GAO, 2009b). The FDA found that only 8% of 510(k) submissions for non–in vitro diagnostic devices contain clinical data, and of those only 11% reference a predicate for which clinical data was provided. Less than 1% of non–in vitro diagnostic 510(k) submissions reference a clinical trial conducted under an approved Investigational Device Exemption application. The majority of 510(k) submissions for in vitro diagnostic devices contain some type of clinical information (FDA, 2010b).

There is no paradigm for devices that is similar to the Phase 0–IV clinical-trials paradigm used in the development, optimization, and registration pathway of drugs and biologics. Device trials are generally designated as either pilot or pivotal, and the specific clinical-trial attributes associated with each of these designations are not standardized or specified.

Some guidance documents focus entirely on preclinical device attributes, and others contain little guidance on clinical testing. For example, the Guidance for Cardiovascular Intravascular Filter 510(k) Submissions states (FDA, 1999) that

it is anticipated that human clinical investigations could be necessary in the development of a “new” vena cava filter to establish its equivalency to currently marketed filters. Such a study may also be necessary for a modified filter design. The need for such a study should be discussed with FDA prior to submission of an investigational device exemption (IDE) submission.

The guidance goes on to advise that “in those cases in which a study is deemed necessary, the sponsor should carefully consider the following items:

• the appropriate study design

• the study hypothesis

• appropriate sample size

• definitions of success and failure

• clinically relevant endpoints necessary for the demonstration of substantial equivalence.”

The guidance provides detailed information on the clinically relevant end points that might be necessary for the demonstration of substantial equivalence and labeling (for example, clinical indications and contraindications for use and warnings). It does not, however, define the other critical components of an appropriate study design, including how to determine an appropriate sample size and what characteristics and end points to use in defining success and failure. No guidance is available on determining clinically relevant issues, such as how to designate the primary aim, which in turn is a driving factor in such study-design decisions as sample size and secondary aims. There is also no guidance on identifying appropriate end

points for measuring the primary or secondary aims. In consultation with the FDA, the manufacturer determines what end points are necessary for the demonstration of substantial equivalence, what aspects should be subjects of clinical testing, or whether any clinical testing is needed. That consultation typically occurs in preinvestigational device exemption discussions between an applicant and the agency.

Although the preinvestigational device exemption meeting results in advice from the FDA on the submission, neither the applicant nor the agency is bound by it. An applicant can request a “binding letter of determination,” however, which obliges both parties to the terms in the letter. The agency reports that few applicants seek binding letters (IOM, 2010).

Both the FDA and industry have cited concerns about the lack of clarity as to when clinical, bench, and other types of information should be required to support the 510(k) submission. For premarket submissions that include clinical evidence, the FDA has described concerns about the variable quality of the studies and about the practice of compiling multiple studies, which may have different study designs (FDA, 2010b, 2010c). Medical-device industry representatives have stated that there is a lack of predictability with the 510(k) review regarding the types of clinical data needed to support the submission (IOM, 2010; Makower et al., 2010).

CDRH proposed developing guidance defining a subset of Class II devices, called “Class IIb” devices, for which clinical information, manufacturing information, or potentially additional evaluation in the postmarket setting would typically be necessary (FDA, 2011a).

Finding 4-8 There is no consistent approach for how the FDA determines the need for clinical data, the type of such data, and the manner in which such data, if available, are integrated into the decision-making process.

Variations in Review of 510(k) Submissions

Because the device types eligible for the 510(k) review process are immensely heterogeneous—with diverse risk profiles, applications of technologies, and relationships with identified predicates—there is an enormous variation in the complexity of 510(k) submissions reviewed by the FDA.

A new submission that has simple and obvious links to a predicate, that has a moderate risk profile, or that has a well-established history of device review may be assigned to a single member of the review staff, who will evaluate it and make a recommendation regarding substantial equivalence to the identified predicate. If unique software, statistical, or clinical issues are raised in the course of the review, consultations with software engineers, statisticians, or physicians may be sought.

A new submission that does not have simple and obvious links to a predicate, that has a higher risk profile, or that has a less established history of device review may be assigned to a multidisciplinary review team of regulatory scientists, often including a biologist, an engineer, a statistician, and a clinician and sometimes including an expert in software or epidemiology. Team reviews may be performed and recommendations developed about substantial equivalence.

In a complicated submission or a submission that raises new or controversial review issues, the FDA may use the expertise of members of its standing advisory panels to answer review questions or provide actual review. The submission is formally assigned to advisory-panel members outside the FDA who have the requisite expertise.

It is not uncommon for the FDA to request additional information to clarify or strengthen a submission during review. The FDA is limited in the types of information that it can request and how that information can be used. The new information can be used only to assess the submission’s claim of substantial equivalence to the predicate(s). If the information needed is straightforward, a reviewer may simply call the submitter to make the request and will not need to put the submission on hold while waiting for a response. If the additional information needed is more extensive or complex, the reviewer will prepare a written letter and put the submission on hold.

Industry has questioned the transparency and credibility of the review process, however, when requests for additional information are seen as irrelevant to the intended clinical use or to the technology used. Industry representatives have also stated that requests made late in the review process are especially burdensome (FDA, 2010d). While the company is preparing a response to the FDA’s request for information, the submission is not considered to be under active review, and the clock for review time is stopped. Responses to the FDA are usually requested within 30 days, but submitters may request an extension if more time is needed.

Another potential contributor to the variation in review time is the “least burdensome” provision discussed in Chapter 2. CDRH’s Task Force on the Utilization of Science in Regulatory Decision Making found that FDA staff reported that industry perceives previous reviews as setting a precedent (FDA, 2010c). As new information about different devices and device types becomes available, the FDA may request different types of data from those of the past. Manufacturers sometimes see increased requests for data as unnecessary and contrary to the “least burdensome” principle (FDA, 2010d). Industry groups also contend that there is a lack of consistency and transparency in the FDA decision-making process and are concerned about lengthening review times, vagueness in the term new types of questions, and the burden associated with down-classifying devices. In particular, some industry groups have stated that the FDA asks for detailed

information on issues that are not clinically relevant or are obvious in light of underlying knowledge of the technology involved in the device. On the other hand, some in the scientific community believe that the agency has not asked even for rudimentary data that would have an important clinical impact (FDA, 2010d). As a result of those issues and concerns, CDRH has recommended that the “least burdensome” provision be more clearly defined (FDA, 2010c).

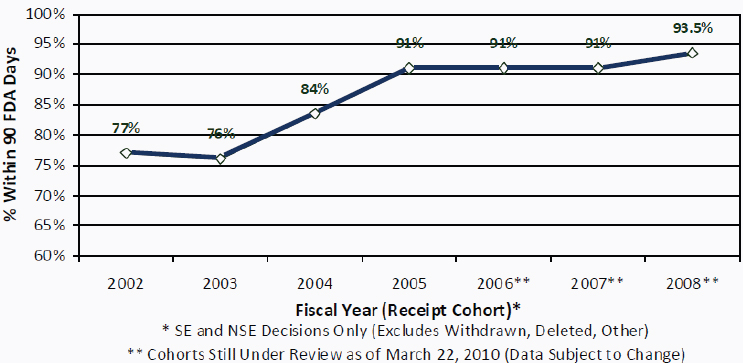

As mentioned before, CDRH is required to respond within 90 days of receipt of a 510(k) submission. In 2009, the FDA’s goal was to review 90% of 510(k) submissions within 90 days and 98% within 150 days (see Figure 4-2) (GAO, 2009b). That goal was met in previous years (see Table 4-1). Given the variability in the 510(k) submissions, CDRH staff report that review periods did not allow sufficient review of complex issues (FDA, 2010c). CDRH staff reported that they were unable to schedule and hold meetings, or respond to sponsors’ requests for information, because of the focus on submission review times (GAO, 2009a).

Data from CDRH’s 510(k) internal report show that the actual review times for most submissions are within the mandated limit (FDA, 2010b). Industry has noted that in an increasing number of submissions CDRH does

FIGURE 4-2 Percentage of 510(k) decisions within 90 FDA days, FY 2002–2008.

NOTE: NSE, not substantially equivalent; SE, substantially equivalent; FDA Days are defined as the time during which a submission is under active review by FDA; “Submitter Days” is the time during which a submission is “on hold” pending the receipt of additional information requested by FDA; “FDA Days” and “Submitter Days” sum to the total length of time from initial FDA receipt of a submission until issuance of a decision.

SOURCE: FDA, 2010b.

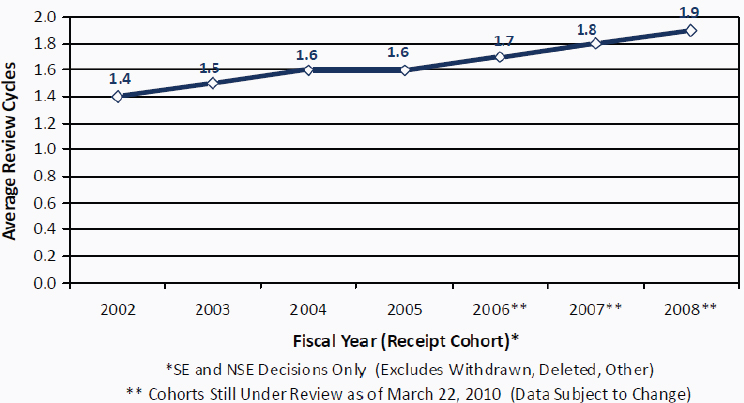

FIGURE 4-3 Number of 510(k) review cycles, FY 2002–2008.

NOTE: NSE, not substantially equivalent; SE, substantially equivalent.

SOURCE: FDA, 2010b.

not meet the mandates (FDA, 2010d). The FDA has stated that its resources are strained, given the complexity of submissions for innovative devices; these submissions require more FDA staff time and generally involve more review cycles (see Figure 4-3). It is possible to assume that complex 510(k) submissions are skewing the response times and increase review cycles, but without a detailed file review it is not possible for the present committee to determine whether this is the case.

Design Controls

The committee was given findings of two studies of the FDA’s recall database (IOM, 2011). The studies assessed recalls associated with 510(k)-cleared products. Among the many measures assessed were the causes behind recalls of Class I 510(k)-cleared devices. Each study presented the recall data by reasons for the recall. The analysis conducted by Hall suggested that 55% of Class I recalls were related to postmarket issues and 45% to premarket issues (IOM, 2011). The analysis conducted by Maisel similarly concluded that about 57% of recalls were due to manufacturing process or device design (IOM, 2011). Given the results of those studies, it is clear that design issues and controls are worth examining more closely.

The FDA requires manufacturers of medical devices to implement

quality system regulations (QSRs),43 which establish current good manufacturing practice requirements for “methods used in, and the facilities and controls used for, the design, manufacture, packaging, labeling, storage, installation, and servicing of all finished devices intended for human use.” The requirements are intended to ensure the safety and effectiveness of medical devices. 21 CFR Part 820 includes general descriptions and suggestions for establishing the following elements of a manufacturing process:

• A management subsystem.

• Design and development controls.

• Production and process controls.

• Corrective and preventive actions.

The regulation requires manufacturers to have the QSRs in place but provides only general guidance for its implementation, not device-specific guidance. The adoption of design control requirements was driven by studies performed by the FDA in the mid-1980s that evaluated the causes of recalls of medical devices. The studies revealed that almost 50% of recalls were attributed to the design and development phase of device manufacture. The FDA had no systematic means of tracking design and development issues. The controls described below would provide a paper trail for the FDA to follow if it inspects a facility involved in a recall. Despite the mandatory implementation of this requirement, device design is still responsible for almost half all Class I and Class II recalls (IOM, 2011; Shuren, 2010).

Manufacturers are required to have design and development controls for all Class II and Class III devices and for several types of Class I devices: any device automated with software, catheters for tracheobronchial suction, surgical gloves, protective restraints, a manual radionuclide applicator system, and a teletherapy radionuclide source. The ultimate implementation and approval of this management structure is left up to the manufacturer; the FDA provides only guidance and suggestions for implementation. A key element of the design-controls system is a list of documents that must accompany each device type produced by the manufacturer and must be maintained by the manufacturer and be available for review in the event of an inspection. The list includes the following:

• Design inputs.

• Design outputs.

• Design review before transfer from design to manufacturing.

• Design validation.

• Design verification.

___________________

4321 CFR pt. 820.

• Design transfer.

• Design changes.

This collection of documents forms what is referred to as the device history record and forms a portion of a larger device master record. The master record describes the life of the device through design iterations, modifications, as well as other documents, and it should contain all relevant information about the design of the device. The master record is what the FDA reviews during an inspection. Manufacturers typically have multiple products and multiple models of each product, however, and each model has a device history record (DHR). An FDA investigator is generally able to review only a small portion of all the manufacturer’s DHRs. It is not clear whether the documents required by the FDA are helpful in determining the reason for a recall or whether the documents provide the information necessary for improving the product or process to eliminate the reason for a recall.

CDRH can request that design-control information be included in a 510(k) submission (FDA, 2010b). The committee did not find data on how often design-control information is requested by CDRH staff as part of 510(k) reviews. CDRH noted in its preliminary internal evaluation that center staff have not received sufficient guidance and training in requesting this type of information from submitters or in when such information is necessary for deciding whether to clear a device (FDA, 2010b).

Device Labeling within the 510(k) Review

General labeling requirements are applicable to various types of devices. There is one general set for over-the-counter devices and another for prescription devices.44 The prescription-device regulation, for instance, says that the label must “[bear] information for use, including indications, effects, routes, methods, and frequency and duration of administration, and any relevant hazards, contraindications, side effects, and precautions under which practitioners licensed by law to administer the device can use the device safely and for the purpose for which it is intended, including all purposes for which it is advertised or represented.”45 This general rule would apply to any prescription device, whether 510(k)-exempt, 510(k)-cleared, or PMA-approved. Moreover, in a few cases, the FDA has issued specific labeling requirements for particular devices.46

Specifically for 510(k)-cleared devices, the 510(k) notification must include “proposed labels, labeling, and advertisements sufficient to describe

___________________

44See Chapter 2 and CFR pt. 801.

4521 CFR § 801.109.

46E.g., 21 CFR § 801.435 (device-specific labeling for latex condoms).

the device, its intended use, and the directions for its use.”47 The FDA is able to review the draft labeling and can negotiate with manufacturers on the text particularly for devices for which clinical study results are included. The final labeling is not cleared as part of the 510(k) clearance. The FDA, however, uses the proposed labeling to determine a device’s intended use for purposes of determining substantial equivalence. Moreover, the draft labeling of a 510(k)-cleared device may be changed at any time—even before initial marketing—not only without FDA approval but even without submission to the FDA. The FDA’s guidance includes information about when labeling changes should be included in a new 510(k) submission. 510(k) sponsors are obliged to “maintain in the historical file any labeling or advertisements in which a material change has been made anytime after initial listing.”48 The FDA investigators might come across the change when conducting an inspection or when investigating a device problem. Otherwise, the FDA can be unaware of labeling changes made once a device is on the market.

In comparison, for PMA-approved devices, labeling is approved as part of the PMA approval process. After PMA approval, all proposed label changes that affect the safety and effectiveness of a device must be submitted to the FDA, and, with a few exceptions (for example, newly acquired information that warrants an immediate strengthened warning or new contraindication), all changes must be approved by the agency before they go into effect.

As discussed above, given that the FDA has relatively narrow mechanisms for addressing off-label use even when substantial risks are identified, it is often in the position of having to make decisions about substantial equivalence without complete information about how the device will be used once it is cleared.

The classification system introduced in the Medical Device Amendments of 1976 had provisions that designated all new medical devices that were introduced into the medical marketplace without predicates as Class III devices on the basis of their novelty regardless of risk. As a result, low-

___________________

4721 CFR § 807.87(e).

4821 CFR § 807.31(b). According to the FDA, material changes include any change or modification in the labeling or advertisements that affects the identity or safety and effectiveness of the device. These changes may include changes in the common or usual or proprietary name, declared ingredients or components, intended use, contraindications, warnings, or instructions for use. Changes that are not material may include graphic layouts, grammar, or correction of typographic errors that do not change the content of the labeling; changes in lot number; and, for devices whose biologic activity or known composition differs in each lot produced, the labeling that states the actual values for each lot.

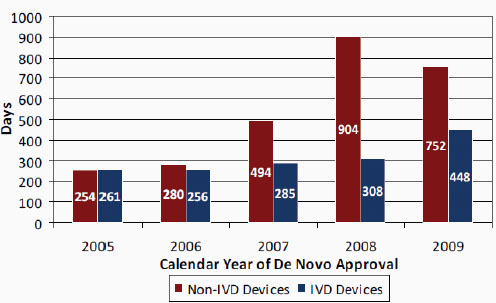

risk or moderate-risk but novel devices would require a PMA application (FDA, 2010g).