1

Introduction

The mission of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is to protect public health by ensuring the safety and security of the products that it regulates—foods, drugs, cosmetics, biologics, veterinary products, medical devices, and products that emit radiation. FDA must also ensure the efficacy of drugs, biologics, and medical devices; and in June 2009, it was given responsibility for regulating tobacco products. Given the vast array of products under its regulatory purview, FDA is faced with an enormous task. Globalization of industries regulated by FDA and the complexity of new products and technologies have created new challenges. Expansion of responsibilities and shrinking of resources over the last 20 years have compounded the challenges, and a recent review noted that “FDA is engaged in reactive regulatory priority setting or a firefighting regulatory posture” (FDA 2007, p. 4). FDA recognized that its current dilemma could be better addressed if risk information were collected and evaluated in a systematic manner. Consequently, FDA and the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) asked the National Research Council (NRC) to convene a committee to develop a framework for evaluating and characterizing the public-health consequences associated with FDA-regulated products or product categories in the context of various decision scenarios. This report, prepared by the Committee on Ranking FDA Product Categories Based on Health Consequences, Phase II, is the response to that request.

THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION AND ITS CENTERS

The modern regulatory functions of FDA date to 1906, when a law that banned interstate commerce in adulterated or misbranded foods and drugs was passed.1 Since then, over 200 laws have shaped the agency into what exists to-

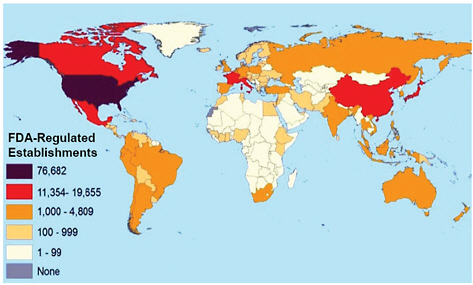

day. FDA is now a federal agency under the jurisdiction of DHHS and has a staff of over 12,000 and a budget of over $3.3 billion (FDA 2010b). FDA has regulatory oversight of over $2 trillion in consumer products (FDA 2010c) and regulates over 375,000 establishments worldwide (FDA 2007; see Figure 1-1). The five centers described below provide regulatory oversight of foods, drugs, biologics, veterinary products, and medical devices. The information provided is not meant to be a comprehensive review of FDA and all its various activities but simply to highlight the breadth of the agency’s responsibilities.

-

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN). CFSAN has the responsibility for safeguarding the nation’s food supply except meat, poultry, and some egg products, which are regulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. CFSAN also has regulatory responsibility over dietary supplements and cosmetics and for ensuring that such products are properly labeled. Premarket approvals are not required for foods, dietary supplements, or cosmetics, but premarket notifications or approvals are required for food additives and color additives. To ensure product quality, selected manufacturing or processing facilities are inspected in conjunction with FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) to ensure that they are in compliance with good manufacturing practice (GMP). Other activities include monitoring the food supply for contaminants, such as melamine, dioxins, and pesticides; developing new methods to speed detection of contaminated or adulterated food; and maintaining and monitoring a database for adverse-event reporting.

FIGURE 1-1 Worldwide distribution of establishments regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Source: FDA 2007, p. 12.

-

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). CDER regulates drug production and distribution and thus has responsibility for ensuring the safety, efficacy, and proper labeling of prescription, generic, and over-the-counter drugs. Drugs require premarket approval, and manufacturing facilities are inspected as part of the approval process. Manufacturing facilities are inspected after drug approval to ensure that GMP is maintained, and drugs are monitored to ensure identity, potency, and content uniformity. To identify unanticipated risks associated with marketed products, CDER collects and evaluates data on drug use and adverse events associated with drug use.

-

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). CBER ensures the safety, purity, potency, and efficacy of biologics, including vaccines, blood and blood products, cells, tissues, and gene therapies. CBER’s processes regarding premarket approval, inspections, and safety surveillance of marketed products are similar to those of CDER, described above. Like CDER, CBER also monitors postmarket problems through an adverse-events reporting database.

-

Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM). CVM ensures that veterinary drugs, animal feeds, and pet foods are safe and secure; that veterinary drugs are effective; and that food generated from treated animals does not contain unsafe drug residues. Like human drugs, veterinary drugs require premarket approvals, and ORA inspects manufacturing facilities to ensure compliance with GMP. CVM establishes standards and monitors animal feed for contaminants. Like the other centers, CVM collects and evaluates data on adverse events associated with veterinary products.

-

Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). CDRH ensures that medical devices are safe and effective and that products that emit radiation are safe. CDRH conducts premarket reviews and monitors the manufacturing processes and uses of its regulated products. ORA conducts the premarket and postmarket inspections of manufacturing facilities, performs laboratory analyses, and reviews imports to ensure compliance with FDA standards. Like the other centers, CDRH monitors postmarket problems through an adverse-events reporting database.

THE COMMITTEE’S TASK AND DECISION SCENARIOS FROM THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION

Given its vast responsibilities, its limited resources, and the difficult decisions that it faces daily, FDA recognized that a systematic approach to evaluating the risks associated with its products or product categories would be valuable. Thus, FDA and DHHS asked NRC to convene a committee that could develop a conceptual framework to characterize the public-health consequences associated with its products or product categories in the context of various decision scenarios (see Appendix B for a verbatim statement of task). Such a framework would provide a common set of metrics that would enable each center to

evaluate the public-health consequences with a common terminology and a similar approach and would allow comparisons within and among disparate programs.

FDA provided the committee with a set of decision scenarios that illustrate the types of decisions encountered by the various centers except the tobacco program (see Appendix C for the scenarios). The scenarios were provided only as examples of the variety of decisions that FDA regularly faces in which public-health consequences are relevant and in which it might be valuable to consider the consequences systematically and consistently, not as scenarios for the committee to address specifically.

As described by FDA (Bertoni 2010), the scenarios represent three types of decisions faced by the centers:

-

Mitigation-selection decisions in which FDA must weigh various alternative strategies for addressing a potential health risk. For example, how should FDA balance potential concerns about product safety with the potential consequences of decreased product availability?

-

Targeting decisions in which FDA must determine which among a broad array of product hazards or potential health benefits should be addressed to obtain the maximum public-health benefit. For example, how should sparse inspection resources be allocated between seafood and fresh produce?

-

Strategic-investment decisions in which research, data collection, and analytic-tool development can reduce scientific uncertainty and improve FDA’s ability to make targeting and mitigation-selection decisions. For example, what public-health concerns should guide a decision about whether to use resources for data collection to improve understanding of food supply-chain safety or for medical-device safety surveillance?

The committee focused on the public-health, scientific, and technologic factors that inform the decisions, although it recognizes that the decisions described above also involve many other factors, including legal and policy considerations.

THE COMMITTEE AND ITS APPROACH TO ITS TASK

Committee members were selected on the basis of expertise in food safety, health economics, medical devices, vaccine safety, pharmacoepidemiology, biostatistics, comparative risk analysis, and decision analysis (see Appendix D for biographic information on the committee). To complete its task, the committee held six meetings. In a public session during one meeting, FDA staff of various centers discussed with the committee their current approaches and data available for making risk-based decisions. The committee reviewed a variety of literature and made several data requests to the agency so that it could develop case studies to illustrate the use of its framework. The committee did not conduct exhaus-

tive literature searches or reviews to acquire the data for the case studies; it used readily available data or made judgments based on the available data and its multidisciplinary expertise. Thus, the committee emphasizes that all information is illustrative and that the case studies are simply provided as examples of how the committee’s framework might be used for the various types of decisions. To be consistent with its statement of task, the committee considered only U.S. users of FDA products and focused on consequences to human health. The committee notes that it was not asked to review or comment on existing decision-making processes at FDA or on the spectrum of risk-based models in development at the agency, and it was not asked to determine how its proposed model would fit within that context.

The committee recognizes that the evaluation of risk is but one factor in the decision-making process. As discussed in the recent report Enhancing Food Safety: The Role of the Food and Drug Administration, “risk decision making takes place in a broader social context” (IOM/NRC 2010, p. 75). FDA must also consider such factors as economic constraints and public-health and welfare concerns of all stakeholders. As noted in that report, “it is critical during the information gathering stage to identify which factors will be considered in the decision-making process” (IOM/NRC 2010, p. 75).

ORGANIZATION OF REPORT

The committee’s report is organized into seven chapters. Chapter 2 describes the proposed risk-characterization framework and the associated risk attributes. Chapters 3, 4, and 5 provide case studies that illustrate the use of the committee’s proposed framework for a mitigation-selection decision, a targeting decision, and a strategic-investment decision, respectively. Chapter 6 provides a case study that examines a targeting decision to set priorities for work that could affect more than one center when choices must be made to allocate agency resources to several pressing needs that arise simultaneously. Chapter 7 describes the lessons learned from developing the case studies and provides the committee’s general conclusions and recommendations. The committee’s letter report, its statement of task, the decision scenarios, the committee biographies, and factors considered important in understanding risk are provided in appendixes to the report.

REFERENCES

Bertoni, M.J. 2010. Opening Remarks. Presentation at the 5th Meeting on Ranking FDA Product Categories Based on Health Consequences, Phase II, February 3, 2010, Washington, DC.

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2007. FDA Science and Mission at Risk: Report of the Subcommittee on Science and Technology, November 2007. Briefing Information. FDA Science Board Advisory Committee Meeting, December 3,

2007 [online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/briefing/2007-4329b_02_00_index.html [accessed Oct. 25, 2010].

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2010a. About FDA: History. U.S. Food and Drug Administration [online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/default.htm [accessed Oct. 25, 2010]

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2010b. Budget Tables: Summary of Changes FY 2011. FY 2011 Food and Drug Administration Congressional Justification [online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/ReportsManualsForms/Reports/BudgetReports/UCM202309.pdf [accessed Oct. 25, 2010].

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2010c. Executive Summary: Introduction, Mission and Performance Budget Overview FY 2011. FY 2011 Food and Drug Administration Congressional Justification [online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/ReportsManualsForms/Reports/BudgetReports/UCM202307.pdf [accessed Oct. 25, 2010].

IOM/NRC (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council). 2010. Enhancing Food Safety: The Role of the Food and Drug Administration. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences.