Summary

The foundation of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was laid in 1906 with the passage of a law that banned interstate commerce in adulterated or misbranded foods and drugs. Over the last century, FDA has evolved and grown into a government agency that now has over 12,000 employees and regulatory oversight for over $2 trillion in consumer products. FDA has the responsibility to ensure the safety and security of foods, drugs, cosmetics, biologics, veterinary products, medical devices, and products that emit radiation. It must also ensure the efficacy of drugs, biologics, and medical devices and, in June 2009, was given responsibility for regulating tobacco products. The decisions that FDA faces daily can range from determining whether a drug should be approved to allocating resources for inspection of food-production facilities. Decisions often need to be made quickly and on the basis of incomplete information. Given the immensity of its task, FDA recognized that a framework for organizing and evaluating risk-based information in a systematic and consistent manner would be valuable. Accordingly, FDA and the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) asked the National Research Council (NRC) to develop a framework that could provide consistent information on health consequences as an aid to decision-making at FDA.

This report, prepared by the Committee on Ranking FDA Product Categories Based on Health Consequences, Phase II, in response to the request from FDA and DHHS, describes a risk-characterization framework that can be used to evaluate and compare the public-health consequences of different decisions concerning a wide variety of products. The framework presented here is intended to complement other risk-based approaches that are in use and under development at FDA, not replace them. The committee recognizes that the public-health-consequence factors highlighted in the framework will seldom, if ever, be the only important considerations in the decision-making process, but they are almost always some of the key considerations.

DECISION-MAKING AT THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION

FDA gave the committee 16 scenarios that highlighted a variety of decisions that FDA regularly faces in which public-health consequences are relevant and for which a systematic and consistent approach for considering risk would be valuable. On the basis of the scenarios, FDA characterized the types of decisions that it faces as mitigation-selection decisions, targeting decisions, and strategic-investment decisions.

-

Mitigation-selection decisions are those in which FDA must weigh various alternative strategies for addressing a potential health risk. For example, how should FDA balance concerns about the safety of a product with the potential consequences of removing the product from the market?

-

Targeting decisions are essentially priority-setting or resource-allocation decisions and focus on how particular resources should be allocated among a broad set of products. For example, how should sparse inspection resources be allocated between seafood and fresh produce?

-

Strategic-investment decisions are longer-term internal decisions about where FDA should invest its resources to enable better risk-informed decision-making. For example, should FDA invest resources to improve collection of data on the food-supply chain or on medical-device surveillance?

The committee notes that there are other ways of categorizing decisions, and some decisions that are within FDA’s authority are difficult to fit within the three categories defined here. However, for purposes of developing a decision-focused risk-characterization framework for FDA, the committee adopted FDA’s categorization of decisions.

THE RISK-CHARACTERIZATION FRAMEWORK

Health consequences are a subset of the larger array of factors that must be considered for any given problem. Because such factors loom large in most FDA decisions, they constitute a reasonable place to start the process of developing a decision framework. The framework offered here builds on the substantial amount of work that has been done on methods for estimating the human-health consequences associated with various risks, hazards, and decisions. It provides a common language for describing potential public-health consequences of decisions, is designed to have wide applicability among all FDA centers, and draws extensively on the well-vetted risk literature to define the relevant health dimensions for FDA decision-making.

The process is straightforward and involves three steps:

-

Step 1. Identify and define the decision context: What decision options are being considered? What are the appropriate end points to evaluate and compare?

-

Step 2. Estimate or characterize the public-health consequences of each option by using the risk attributes that are described below. The values of the risk attributes should be summarized in a table to facilitate comparison of the options.

-

Step 3. Use the completed characterization as a way to compare decision options and to communicate their public-health consequences within the agency, to decision-makers, and to the public; use the comparison with other decision-relevant information to make informed decisions.

Although the steps can be easily articulated, they involve thought and effort to complete. The framework is not a cookbook and will require FDA to exercise judgment in how it is used. Completing the attribute table (Step 2) may be relatively simple, or it may require substantial research and modeling or even additional data collection and analysis. The decision needs and the available resources should determine how much time and effort should be put into implementing the risk-characterization framework.

THE RISK ATTRIBUTES

Defining a suitable set of risk attributes to characterize the public-health consequences necessary for Step 2 of the framework was a challenging task. Risks are often characterized by a single attribute, such as the number of deaths that could occur as a result of a hazard being evaluated or the probability that an exposed individual will experience an identified adverse effect. However, defining the risk attributes for this framework required recognition of the multidimensional nature of risk.

Consideration of the traditional risk-assessment paradigm gave rise to one set of attributes to characterize health risks. Thus, the committee defined exposed population, mortality, and morbidity as the attributes to use to determine the number, type, and rate of occurrence of adverse health effects that could result from implementation of a particular decision option.

-

Exposed population is related to the size of the population and the characteristics of the people who are potentially affected by the decision being considered.

-

Mortality can be described as the number of deaths that will result from the use (or absence) of the product that is the subject of the decision options being evaluated.

-

Morbidity refers to the illnesses or injuries that are attributable to the decision options being evaluated. This attribute requires a slightly more complex set of metrics that acknowledge differences in severity and duration of a health effect, and the committee therefore proposed the following metrics: severe adverse health effects (effects identified as life-threatening, requiring hospitalization, or leading to substantial, persistent, or permanent disability related to impaired organ function), less severe adverse health effects (effects that require some level of medical care but are not the more serious effects described above), and adverse quality-of-life health effects (effects that may or may not require medical care but have been found to diminish a person’s subjective quality of life, such as anxiety, depression, pain, discomfort, and reduced mobility).

Studies of risk perception and public attitudes about risks have consistently shown that although numbers of deaths and illnesses or injuries matter, so do other factors, such as whether a risk is voluntary and how much control a person has over the risks. Thus the committee identified a second set of risk attributes on the basis of the risk-ranking and risk-perception literature that would be applicable to FDA decision-making. Those attributes are personal controllability, ability to detect adverse health effects, and ability to mitigate (or reduce) adverse health effects.

-

Personal controllability describes the degree to which a person can eliminate or reduce his or her own risks through voluntary action by avoiding exposure to the risk entirely, by reducing the likelihood that exposure will lead to harm, or by minimizing the effects if they do occur.

-

Ability to detect adverse health effects refers to the ability of informed institutions to detect population-level adverse effects that result from the use (or absence) of the product that is being considered.

-

Ability to mitigate adverse health effects refers to the ability of institutions to manage, reduce, or otherwise control any expected or unexpected adverse health effects associated with the product that is being evaluated, assuming that such effects exist and are detected.

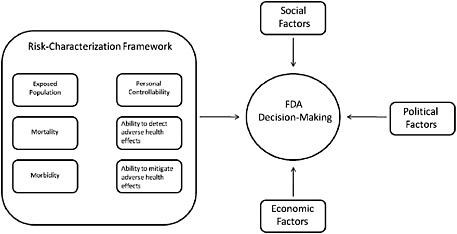

The attributes proposed here do not preclude the use of additional decision-specific criteria but do capture the major consequences that should be considered in any public-health-related decision. Although the committee recognizes that FDA often must consider other factors—such as economic, social, and political factors—in addition to the public-health consequences in its decision-making (see Figure S-1), it finds that careful and consistent evaluation of the public-health consequences of various options is an essential component of good decision-making.

FIGURE S-1 Factors in FDA decision-making.

UNCERTAINTY AND ESTIMATING CONSEQUENCES

Using a single set of risk attributes with specified metrics to evaluate public-health-related decisions entails substantial complexities. For the wide array of decisions that FDA must make, varied amounts of information will be available to estimate the risk attributes for each decision option. For some attributes, large volumes of data may exist for developing or supporting estimates, such as the mortality risk related to some drug. For others, there may be an array of detailed computer models that can help in projecting estimates. For still others, there may be scant data or models available, and direct assessment of the effects by experts will be the only alternative. It is not within the present committee’s scope to evaluate, compare, or recommend specific approaches or models for risk quantification. The committee simply urges FDA to bring the best available data and expertise to bear on the evaluation that would be consistent with the importance of the decision being evaluated and the time and resources available to complete the assessment.

The assessment, quantification, and communication of the uncertainty associated with the estimates are essential. Although categorical measures—such as “likely,” “very unlikely,” and “possible”—may make the assessment task more palatable, it also makes it considerably less useful. The very ambiguity that provides comfort makes the task of communicating and comparing uncertainties extremely difficult. The committee recommends that the uncertainty in the estimates be described as quantitatively as possible by using summary measures of a probability distribution that describes the estimate of interest. Specifically, the committee suggests that uncertainty be summarized by the 5th, 50th (median), and 95th percentiles of a probability distribution. Although the percentiles are precisely defined, their cognitive interpretation should not be lost. The 5th percentile represents a value below which the actual value is not likely to fall, and

similarly, the 95th percentile represents a value above which the actual value is not likely to fall. With training and practice, an analyst can assess an accurate representation of those percentiles from experts using easily described thought experiments, simple tools, and standard protocols. The committee emphasizes that it is always possible to collect more data and do more analyses to try to develop “better” estimates, but there will always be uncertainty, and decisions often must be made on the basis of existing information. Quantifying what is known and what is not known (uncertainty) is an important way to ensure that decisions are as well informed as possible.

CASE STUDIES: LESSONS LEARNED

The committee applied its risk-characterization framework to four hypothetical decision scenarios, each of which was based on scenarios provided by FDA (see Box S-1). In conducting the case-study exercises, the committee reached several conclusions. First, the committee found that it was possible to characterize different decision options by using the risk attributes and that estimates could be made by using existing data and expert judgment. The judgments that were required were not always easy, and committee members were not always comfortable in making them. In the end, however, the committee concluded that the resulting attribute tables would provide useful, relevant, and sufficiently accurate information to be valuable in decision-making.

Second, the value of multiple points of view became evident as the committee developed the case studies. Subject-matter experts were needed to identify and evaluate data relevant to the case studies, and decision analysts were needed to provide the guidance for using the data to estimate the attribute values for the options being compared. The development and analysis of each case study required substantial involvement of both subject matter experts and decision analysts.

Third, the committee found that it was critical in each case to define the decision options to be evaluated and compared clearly so that appropriate risk information for the decision-making process could be obtained. In all cases, analytic reasoning and basic structuring tools, such as influence diagrams, were used to identify the various factors that needed to be considered to develop estimates of the public-health consequences of the alternative decision options.

Fourth, the committee encountered many challenges in finding and interpreting data. In its interactions with FDA, the committee came to recognize that in many cases the agency has a substantial amount of data but the data are not collected, organized, or accessible in a format that is useful to support decisions. The committee emphasizes that simply collecting more data is not necessarily the best use of resources; collecting more relevant data and organizing them so that they are useful in decision-making is the key.

|

BOX S-1 Description of Case Studies Mitigation-Selection Decisions. For one case study, the committee considered a hypothetical decision of whether to withdraw a vaccine from the market. It was based on a real-world example in which concerns were raised about a higher-than-expected rate of an adverse effect after vaccination. The committee attempted to look at the situation and the decision options as they were understood at the time when concerns were noted. Although the manufacturer ultimately chose to remove the product from the market, the decision of whether to revoke vaccine licensure is an example of one type of decision that FDA could face in similar circumstances. Targeting Decisions. For another case study, the committee evaluated the potential public-health consequences of foodborne illness associated with three specific food categories, assuming the current regulatory and inspection regime. The three food categories selected were chosen to highlight products that are inherently different with respect to level of processing, origin, and potential risks. The committee describes how the evaluation could be used directly for ranking or comparing the food categories on the basis of risk or could serve as input into decisions for allocating inspection resources among the food categories to maximize protection of the nation’s food supply. Another case study also examined a targeting decision. In this case study, the committee assumed that an analytic laboratory receives many demands from field investigators to test products for a potential contaminant and that extensive testing of any one product with the testing methods available would overwhelm laboratory resources. Before other FDA resources are redirected or outside laboratories are engaged, some sense of the magnitude of the problem must be ascertained. The framework is used to characterize and compare the public-health consequences associated with potential contamination of the given products. Strategic-Investment Decisions. Because recalls of implanted medical devices are based partly on postmarket-surveillance data, the committee decided to examine a hypothetical situation in which FDA is deciding whether to invest resources in enhanced postmarket-surveillance systems for two specific medical devices—one an established device used extensively across the country and the other an emerging device in limited use. The committee defined the enhanced surveillance systems as furthering the goal of finding types and patterns of unexpected events. Such information should lead to identification of problems in design, implantation processes, clinical interventions, or manufacturing variances; early detection of such problems should lead to improvements. The framework is used to characterize the potential benefits of enhanced surveillance relative to current surveillance approaches. |

Fifth, expert judgment and data were inextricably intertwined in how the committee completed each of the case studies. For some case studies, the committee did not have much direct information; in others, adequate data were available. In all cases, assumptions had to be made to interpret the data and complete the attribute table. Although the committee recognizes FDA’s strong preference for “data” over “expert judgment” as the basis of any estimates or decisions, it is important to recognize that expert judgment is always present. When decisions must be made immediately, the committee’s suggested approach can provide useful information about the public-health consequences of various options in a clear and consistent way on the basis of the best information available at the time the decision must be made. When there is ample time to evaluate and compare decision options, the suggested approach can highlight where additional information would help to differentiate between options (that is, it can help to target information collection) and provide a clear and consistent way to compare the options.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

To aid decision-making, FDA should consider using the concepts defined by the risk-characterization framework and particularly the risk attributes defined in the present report for discussing risk-related aspects of various decisions. Considering the outcomes of alternative decisions in terms of the attributes identified here will begin to establish consistency in risk vocabulary throughout the agency. As FDA begins to use the risk-characterization framework, it may find that some aspects of the approach need to be modified. Such modifications are entirely appropriate; the approach should evolve to meet FDA’s needs as staff gain experience in implementing it.

The committee recognizes that precise predictions of the outcomes of different decisions based on the risk attributes may be difficult to develop. Data may be lacking, and scientists may be uncomfortable in making, or even unwilling to make, the necessary judgments to estimate the risk attributes. However, the committee emphasizes that decisions in which risk information could be valuable are made regularly and recommends that FDA use internal or external experts who are trained in and comfortable with decision analysis, risk assessment, risk management, and specifically the assessment of uncertainties to facilitate the use of the committee’s framework.

Changing the organizational culture and its approach to decision-making is a daunting task in any organization. However, FDA is confronted with complex decisions every day, and new approaches are needed to meet the challenges of the future. Using the risk-characterization framework to evaluate the effects of different decisions in terms of the risk attributes described in this report can provide information that is useful in choosing among alternatives.