2

Preventive Services Defined by the ACA

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) defined covered preventive health services for all patient populations to be those with Grade A and B recommendations made by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF or the Task Force); for adolescents, the Bright Futures recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and for all patient populations, recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). The USPSTF, AAP, and ACIP are national authorities on health with defined processes for generating clinical recommendations. A summary of the methods that these entities use to arrive at recommendations and the actual recommendations follows.

UNITED STATES PREVENTIVE SERVICES TASK FORCE

The Task Force is an independent panel composed of nonfederal primary care clinicians, health behavior specialists, and methodologists. Its mission is twofold: (1) assess the benefits and harms of preventive services for people asymptomatic for the target condition on the basis of age, gender, and risk factors for disease; and (2) make recommendations about which preventive services should be incorporated into routine primary care practice. The USPSTF is now entering its 27th year of existence, and the medical community considers its methodologies and resulting recommendations to be the “gold standard” for evidence-based clinical practice in preventive services (USPSTF, 2008b).

TABLE 2-1 USPSTF Grade Definitions

| Grade | Definition | Suggestions for Practice |

| A | The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. | Offer or provide this service. |

| B | The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate degree of certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. | Offer or provide this service. |

| C | The USPSTF recommends against routinely providing the service. There may be considerations that support providing the service in an individual patient. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. | Offer or provide this service only if other considerations support the offering or providing the service in an individual patient. |

| D | The USPSTF recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. | Discourage the use of this service. |

| I Statement | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting; and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. | Read the clinical considerations section of USPSTF Recommendation Statement. If the service is offered, patients should understand the uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms. |

SOURCE: USPSTF, 2008a.

The charge of the Task Force is limited in scope: “its recommendations address primary or secondary preventive services targeting conditions that represent a substantial burden in the United States and that are provided in primary care settings or available through primary care referral” (USPSTF, 2008b). These recommendations are intended to inform primary care providers as they care for individual patients in primary care practice. They are not intended to determine which preventive health care services health insurers should be required to cover. The methodology used in developing Task Force clinical recommendations does not take into consideration many nonclinical issues related to health care coverage (USPSTF, 2011). USPSTF uses a grade system, which is described in Table 2-1.

USPSTF Methodology

Task Force recommendations and their accompanying evidence reports are produced through the collaborative efforts of the USPSTF, the Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Evidence-based Practice Centers (EPCs), and partner organizations. AHRQ provides methodological, technical, scientific, and administrative support to the Task Force. EPCs aid the USPSTF by developing technical reports, evidence summaries and reports, and systematic reviews that target new topics under consideration by the Task Force or that update ones addressed previously. The USPSTF uses systematic evidence reviews produced primarily by the Oregon EPC (under contract by AHRQ) and occasionally uses reviews and other analyses conducted by other groups, depending on the topic under consideration. Partner organizations consist of federal partners (examples include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], the U.S. Department of Defense, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Food and Drug Administration [FDA]) and organizations representing primary care professionals (examples include the American Academy of Family Physicians [AAFP], the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], the American Medical Association [AMA], and AAP). They contribute expertise to the evaluation process and comment on preliminary drafts of Task Force recommendation statements and the accompanying evidence reports. A step-by-step overview of the process of recommendation development, from topic selection to recommendation dissemination, follows. The average amount of time required to complete this process is 21 months (USPSTF, 2011).

1. Topic Selection—USPSTF

EPCs, Task Force members, organizations, and individuals can nominate topics through a publicly accessible website, as well as through solicitations to partner organizations and the Federal Register. On the basis of these submissions, the Task Force Topic Prioritization Work Group periodically updates a prioritized list of topics to be addressed either for the first time or for updating during the year.

2. Work Plan Development—AHRQ, EPCs, USPSTF

Prioritized topics are appointed to “topic teams,” consisting of USPSTF “leads,” AHRQ staff (including a Medical Officer), and EPC members. The topic team develops preliminary work plans from the work assignment that AHRQ has issued to the team. The work plan includes the analytic framework, key questions, the literature search strategy, and a timeline for recommendation dissemination.

3. External Work Plan Peer Review—Outside Experts

Work plans for new topics are sent to a limited number of outside experts in appropriate fields for their comments and review.

4. Approval of Work Plan—USPSTF

The topic team presents work plans for new topics to the entire Task Force. The Task Force then evaluates and requests any revisions to the work plan that it deems necessary. The work plan is then edited by the EPC in accordance with the Task Force’s requests and is finalized.

5. Draft Evidence Report—EPC

The EPC next conducts a systematic evidence review addressing the key questions posed by the Task Force in the work plan, and generates a draft evidence report.

6. Peer-Review of Draft Evidence Report—USPSTF, Content Area Experts, Federal Partners

Draft evidence reports are sent to Task Force leads, content area experts, federal partners, and other partner organizations for review and comment.

7. Development of Draft Recommendation Statement—USPSTF, AHRQ

Concomitant with the draft evidence report review process, Task Force leads collaborate with the AHRQ Medical Officer to discuss and draft a preliminary recommendation statement.

8. Vote on Draft Recommendation Statement—USPSTF

The Task Force is presented with the peer-reviewed evidence report findings by the EPC and the preliminary recommendation statement by the Task Force leads at one of three annual meetings that include the USPSTF, AHRQ, the EPC, and representatives from the partner organizations. The entire Task Force, including the leads, discusses the evidence and debates the language of the recommendation statement until a consensus is reached and the statement passes a vote. The revised recommendation statement is then sent to Task Force leads for completion and editing prior to external review.

9. Final Evidence Report—EPC

The EPC revises the evidence report in response to comments from the federal partners, content area experts, and Task Force leads. The EPC then sends a summary of the comments and how the comments were addressed to AHRQ. AHRQ staff then review, approve, and finalize the revised evidence report. The EPC then prepares the finalized evidence report for submission to a peer-reviewed journal for publication. The final technical report is also made available on the AHRQ website.

10. Review of Draft Recommendation Statement—Federal and

Primary Care Professional Organization Partners and the Public

The newly revised and approved recommendation statement is sent to relevant federal and primary care professional organization partners for review and comment. The statement is also posted on the AHRQ website for one month for public comment.

11. Approval of Final Recommendation Statement—USPSTF

Task Force leads edit the recommendation statement on the basis of the comments received from the federal and primary care professional organization partners and the public after discussion with the AHRQ Medical Officer.

12. Release of Recommendation Statement and

Evidence Report—Peer-Reviewed Journals

Recommendation statements and the accompanying EPC evidence report-derived manuscript are often published simultaneously in the professional journals Annals of Internal Medicine (adult topics) or Pediatrics (child/adolescent topics) and must go through the respective journal’s peer-review process before publication. They are occasionally published in other journals (USPSTF, 2008b).

Preventive services relevant to women that have a grade of A or B from the USPSTF are listed in Table 2-2.

TABLE 2-2 USPSTF Preventive Services Relevant to Women That Have a Grade of A or B

| Topic | Description | Grade |

| Alcohol misuse counseling |

The USPSTF recommends screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse by adults, including pregnant women, in primary care settings. |

B |

| Anemia screening: pregnant women |

The USPSTF recommends routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic pregnant women. |

B |

| Aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD): women |

The USPSTF recommends the use of aspirin for women age 55 to 79 years when the potential benefit of a reduction in ischemic strokes outweighs the potential harm of an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage. |

A |

| Bacteriuria screening: pregnant women |

The USPSTF recommends screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria with urine culture for pregnant women at 12 to 16 weeks’ gestation or at the first prenatal visit, if later. |

A |

| Blood pressure screening |

The USPSTF recommends screening for high blood pressure in adults aged 18 and older. |

A |

| BRCA screening, counseling about |

The USPSTF recommends that women whose family history is associated with an increased risk for deleterious mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes be referred for genetic counseling and evaluation for BRCA testing. |

B |

| Breast cancer preventive medication |

The USPSTF recommends that clinicians discuss chemoprevention with women at high risk for breast cancer and at low risk for adverse effects of chemoprevention. Clinicians should inform patients of the potential benefits and harms of chemoprevention. |

B |

| Breast cancer screeninga |

The USPSTF recommends screening mammography for women, with or without clinical breast examination, every 1–2 years for women aged 40 and older. |

B |

| Breastfeeding counseling |

The USPSTF recommends interventions during pregnancy and after birth to promote and support breastfeeding. |

B |

| Topic | Description | Grade |

| Cervical cancer screening |

The USPSTF strongly recommends screening for cervical cancer in women who have been sexually active and have a cervix. |

A |

| Chlamydial infection screening: non-pregnant women |

The USPSTF recommends screening for chlamydial infection for all sexually active non-pregnant young women aged 24 and younger and for older non-pregnant women who are at increased risk. |

A |

| Chlamydial infection screening: pregnant women |

The USPSTF recommends screening for chlamydial infection for all pregnant women aged 24 and younger and for older pregnant women who are at increased risk. |

B |

| Cholesterol abnormalities screening: women 45 and older |

The USPSTF strongly recommends screening women aged 45 and older for lipid disorders if they are at increased risk for coronary heart disease. |

A |

| Cholesterol abnormalities screening: women younger than 45 |

The USPSTF recommends screening women aged 20 to 45 for lipid disorders if they are at increased risk for coronary heart disease. |

B |

| Colorectal cancer screening |

The USPSTF recommends screening for colorectal cancer using fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy, in adults, beginning at age 50 years and continuing until age 75 years. The risks and benefits of these screening methods vary. |

A |

| Depression screening: adolescents |

The USPSTF recommends screening of adolescents (12–18 years of age) for major depressive disorder when systems are in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, psychotherapy (cognitive-behavioral or interpersonal), and follow-up. |

B |

| Depression screening: adults |

The USPSTF recommends screening adults for depression when staff-assisted depression care supports are in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up. |

B |

| Diabetes screening |

The USPSTF recommends screening for type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic adults with sustained blood pressure (either treated or untreated) greater than 135/80 mm Hg. |

B |

| Topic | Description | Grade |

| Folic acid supplementation |

The USPSTF recommends that all women planning or capable of pregnancy take a daily supplement containing 0.4 to 0.8 mg (400 to 800 µg) of folic acid. |

A |

| Gonorrhea screening: women |

The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen all sexually active women, including those who are pregnant, for gonorrhea infection if they are at increased risk for infection (that is, if they are young or have other individual or population risk factors). |

B |

| Healthy diet counseling |

The USPSTF recommends intensive behavioral dietary counseling for adult patients with hyperlipidemia and other known risk factors for cardiovascular and diet-related chronic disease. Intensive counseling can be delivered by primary care clinicians or by referral to other specialists, such as nutritionists or dietitians. |

B |

| Hepatitis B screening: pregnant women |

The USPSTF strongly recommends screening for hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women at their first prenatal visit. |

A |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screening |

The USPSTF strongly recommends that clinicians screen for HIV all adolescents and adults at increased risk for HIV infection. |

A |

| Obesity screening and counseling: adults |

The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen all adult patients for obesity and offer intensive counseling and behavioral interventions to promote sustained weight loss for obese adults. |

B |

| Osteoporosis screening: women |

The USPSTF recommends screening for osteoporosis in women aged 65 years or older and in younger women whose fracture risk is equal to or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman who has no additional risk factors. |

B |

| Rh incompatibility screening: first pregnancy visit |

The USPSTF strongly recommends Rh (D) blood typing and antibody testing for all pregnant women during their first visit for pregnancy-related care. |

A |

| Topic | Description | Grade |

| Rh incompatibility screening: 24–28 weeks gestation |

The USPSTF recommends repeated Rh (D) antibody testing for all unsensitized Rh (D)-negative women at 24–28 weeks’ gestation, unless the biological father is known to be Rh (D)-negative. |

B |

| Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) counseling |

The USPSTF recommends high-intensity behavioral counseling to prevent STIs for all sexually active adolescents and for adults at increased risk for STIs. |

B |

| Tobacco use counseling and interventions: non-pregnant adults |

The USPSTF recommends that clinicians ask all adults about tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for those who use tobacco products. |

A |

| Tobacco use counseling: pregnant women |

The USPSTF recommends that clinicians ask all pregnant women about tobacco use and provide augmented, pregnancy-tailored counseling to those who smoke. |

A |

| Syphilis screening: nonpregnant persons |

The USPSTF strongly recommends that clinicians screen persons at increased risk for syphilis infection. |

A |

| Syphilis screening: pregnant women |

The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen all pregnant women for syphilis infection. |

A |

a HHS, in implementing ACA under the standard that it sets out in revised Section 2713(a)(5) of the Public Health Service Act, uses the 2002 recommendation on breast cancer screening of the USPSTF.

SOURCE: USPSTF, 2010b.

BRIGHT FUTURES—AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

The HHS Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau established the Bright Futures project in 1990 with the mission to “promote and improve the health, education, and well-being of infants, children, adolescents, families, and communities” (AAP, 2008). It is a “set of principles, strategies, and tools that are theory based and system oriented that can be used to improve the health and well-being of all children through culturally appropriate interventions that address the

current and emerging health promotion needs at the family, clinical practice, community, health system, and policy levels” (AAP, 2008). The most recent report, published in 2008, was developed through the collaborative efforts of four multidisciplinary panels consisting of experts in health during infancy, early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence and was then reviewed by more than 1,000 educators, public health and health care professionals, child health advocates, and parents.

The Bright Futures Steering Committee used three approaches to develop its guidance and recommendations and described these approaches as follows:

- “Multidisciplinary Expert Panels were convened to write recommendations for Bright Futures visit priorities, the physical examination, anticipatory guidance, immunizations, and universal and selective screening topics for each age and stage of development. In carrying out this task, the Expert Panels were charged with examining the evidence for each recommendation, and evidence was an important consideration in the guidance they provided. However, lack of evidence was sometimes problematic for the physical examination (the elements of which can be considered screening interventions) and for counseling interventions. For these components, the Expert Panels relied on an indirect approach buttressed by their expertise and clinical experience” (AAP, 2008).

- The Evidence Panel conducted literature searches for key questions using the MEDLINE® database of the National Library of Medicine. Key themes were searched in the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) database to determine the most appropriate search terms. Searches were limited to clinical trials, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials. Other limits included English language and designations for age, when appropriate. Standardized terms were used for counseling (i.e., counseling, primary prevention, health promotion, health education, and patient education) and for screening (i.e., mass screening and risk assessment). The Evidence Panel also used the systematic

- A Bright Futures Evidence Panel, composed of consultants who are experts in finding and evaluating evidence from clinical studies, was convened to examine studies and systematic evidence reviews and to develop a method of informing readers about the strength of the evidence.

evidence reviews performed for the USPSTF and the Cochrane Collaboration [the publisher of Cochrane Reviews of primary research in human health care and health policy]. This approach was by no means exhaustive, but it did provide an assessment of the most relevant literature. (AAP, 2008)

3. “Throughout the Guidelines development process, the Project Advisory Committee and Expert Panels consulted with individuals and organizations with expertise and experience in a wide range of topic areas. The entire Guidelines document also underwent public review twice in 2004 and once in 2006. More than 1,000 reviewers, representing national organizations concerned with infant, child, and adolescent health and welfare, provided nearly 3,500 comments. The contributions of these reviewers provided an opportunity to refine the guidelines and strengthen the scientific base for the guidance provided” (AAP, 2008).

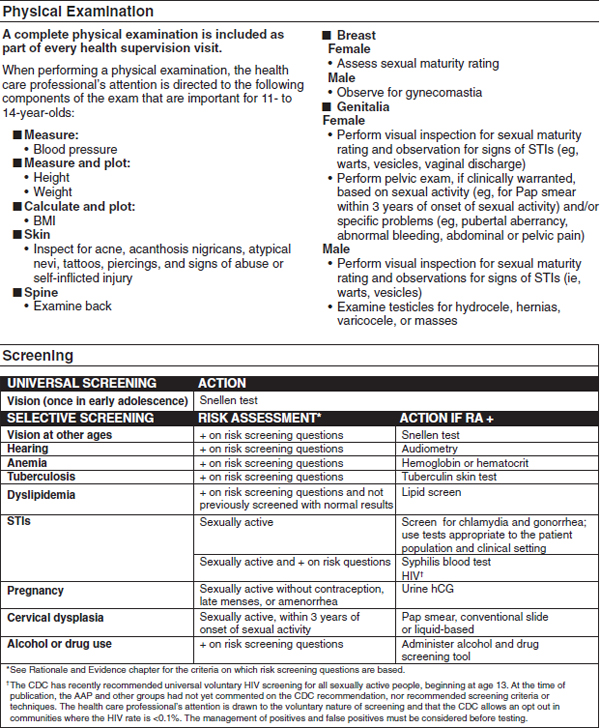

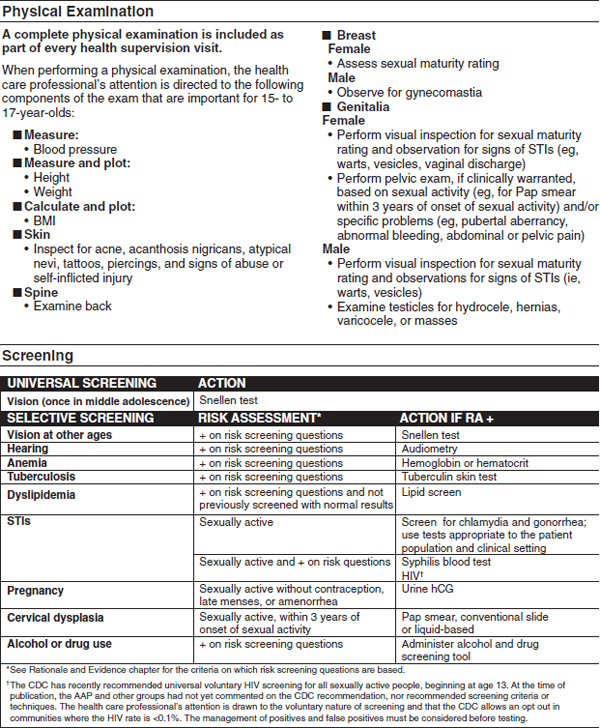

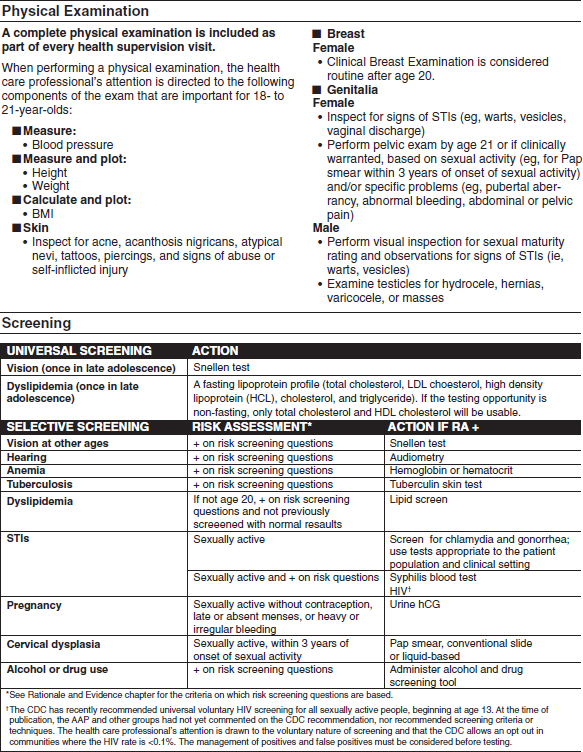

Bright Futures describes its guidelines as “evidence informed rather than fully evidence driven” (AAP, 2008) and takes a broader view of prevention that is less focused on specific conditions and more on general health guidance (e.g., aggregating services into health supervision visits and extensive anticipatory guidance). Like the USPSTF, Bright Futures does not directly comment on insurance coverage, but unlike the USPSTF, Bright Futures does not have categories regarding services comparable to “C” or “I” grades that do not definitively recommend for or against a particular service. Bright Futures intends to leave no gaps in its recommendations, supplementing the evidence where needed with experience and expert opinion so that clinical guidance is always provided. Figures 2-1, 2-2, and 2-3 present the Bright Futures recommendations for adolescents and outline the preventive services that are covered for adolescent women in the ACA. In addition to the information in the tables shown in Figures 2-1 to 2-3, Bright Futures also provides extensive anticipatory guidance on a range of health matters in the context of discussing health issues with adolescents. These measures do not provide action steps and are not suitable for summary in a structured format.

FIGURE 2-1 Adolescence 11–14 year visits.

ABBREVIATIONS: AAP = American Academy of Pediatrics; BMI = body mass index; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; hCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; RA = risk assessment; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

SOURCE: AAP, 2008. Used with permission of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Bright Futures—Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Third Edition, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008.

FIGURE 2-2 Adolescence 15–17 year visits.

ABBREVIATIONS: AAP = American Academy of Pediatrics; BMI = body mass index; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; hCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; RA = risk assessment; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

SOURCE: AAP, 2008. Used with permission of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Bright Futures—Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Third Edition, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008.

FIGURE 2-3 Adolescence 18–21 year visits.

ABBREVIATIONS: AAP = American Academy of Pediatrics; BMI = body mass index; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; hCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; RA = risk assessment; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

SOURCE: AAP, 2008. Used with permission of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Bright Futures—Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Third Edition, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008.

ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON IMMUNIZATION PRACTICES

ACIP is the sole federal government entity that provides written recommendations for delivering vaccines to children and adults in the general population. It provides guidance and recommendations to HHS and the CDC on matters regarding the approval, administration, and safety of vaccines. Its goal is to reduce the prevalence of vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States and bolster the safe use of vaccines and other related biological products. ACIP is comprised of 15 voting immunization-related experts and 34 other representatives from liaison organizations and federal agencies that oversee national immunizations programs (CDC, 2011a).

ACIP Methodology

The ACIP General Recommendations Work Group (GRWG) revises the General Recommendations on Immunization every 3 to 5 years. Relevant topics are those identified by ACIP to be topics that relate to all vaccines, including timing and spacing of doses, vaccine administration procedures, and vaccine storage and handling. New topics are often added when ACIP decides that previous ACIP statements on general issues, such as combination vaccines, adolescent vaccination, and adult vaccination, should be revised and combined with the General Recommendations on Immunization (CDC, 2011b).

The recommendations in the 2011 GRWG report are based not only on available scientific evidence but also on expertise that comes directly from a diverse group of health care providers and public health officials. GRWG includes “professionals from academic medicine (pediatrics, family practice, and pharmacy); international (Canada), federal, and state public health professionals; and a member of the nongovernmental Immunization Action Coalition” (CDC, 2011b).

ACIP committee work groups comprising an ACIP member chair, a CDC subject-matter expert, and at least two ACIP members meet during the year to perform analyses of vaccine-related data and generate potential policy recommendations to be presented to the committee. These analyses include review of the available scientific literature on the immunizing agent, morbidity and mortality from the disease in the U.S. population, recommendation statements issued by other professional organizations, results of clinical trials with the immunizing agent, cost-effectiveness projections, and the feasibility of incorporating the vaccine into preexisting U.S. immunization programs. Draft recommendations are then subjected to further review by the FDA, CDC, ACIP members, external expert consultants, and other relevant federal agencies. Work group findings and potential recommendations are presented to ACIP at one of three annual open meetings and

are deliberated upon by the committee. Public comments are heard at the meetings and taken into consideration during the deliberations. A majority vote is then conducted to pass a recommendation that includes guidance regarding the route of administration and dosing intervals, contraindications and precautions, and target groups for immunization. Recommendations are published on the ACIP website and in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (Smith et al., 2009).

ACIP functions in a unique position because its recommendations are relevant to the general population and to some quite specific subpopulations, but its recommendations focus on efficacy and safety for intended populations. Some of its recommendations are not intended for general clinical use (e.g., recommendations for international travelers), are not intended for the entire population (e.g., recommendations for high-risk groups such as health care workers), or require specific guidance in footnotes for special circumstances (e.g., allergies and immunosuppression).

Table 2-3 lists the FDA-Licensed Combination Vaccines, and Table 2-4 lists ACIP-recommended vaccines that are covered without cost sharing as part of the ACA.

TABLE 2-3 FDA-Licensed Combination Vaccines

|

|

|||

| Vaccine | Trade Name (Year Licensed) | Age Range | Routinely Recommended Ages |

|

|

|||

| HepA-HepB | Twinrix (2001) | ≥18 years | Three doses on a schedule of 0, 1, and 6 months |

| MMRV | ProQuad (2005) | 12 months–12 years | Two doses, the first at 12–15 months, the second at 4–6 years |

|

|

|||

ABBREVIATIONS: HepA = hepatitis A; HepB = hepatitis B; MMRV = measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella.

SOURCES: AAP, 2009; CDC, 2011.

TABLE 2-4 Recommended and Minimum Ages and Intervals Between Vaccine Doses

|

|

||||

| Vaccine and Dose Number | Recommended Age for This Dose | Minimum Age for This Dose | Recommended Interval to Next Dose | Minimum Interval to Next Dose |

|

|

||||

| LAIV (intranasal)a | 2–49 years | 2 years | 1 month | 4 weeks |

| MCV4-1b | 11–12 years | 2 years | 5 years | 8 weeks |

| MCV4-2 | 16 years | 11 years (+8 weeks) |

||

| HPV-1c | 11–12 years | 9 years | 2 months | 4 weeks |

| HPV-2 | 11–12 years (+2 months) |

9 years (+4 weeks) |

4 months | 12 weeks |

| HPV-3d | 11–12 years (+6 months) |

9 years (+24 weeks) |

||

| Td | 11–12 years | 7 years | 10 years | 5 years |

| Tdap | 11–12 years | 7 years | ||

|

|

||||

NOTE: Combination vaccines are available. Use of licensed combination vaccines is generally preferred to separate injections of their equivalent component vaccines. When combination vaccines, the minimum age for administration is the oldest age for any of the individual components; the minimum interval between doses is equal to the greatest interval of any of the individual components. Information on traveler vaccines, including typhoid, Japanese encephalitis, and yellow fever, is available at http://www.cdc.gov/travel. Information on other vaccines that are licensed in the United States but not distributed, including anthrax and smallpox, is available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov.

ABBREVIATIONS: LAIV = live, attenuated influenza vaccine; MCV4 = quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine; HPV-1 to HPV-3 = human papillomavirus doses 1 to 3, respectively; Td = adult tetanus and diphtheria toxoids; Tdap = tetanus and reduced diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (for adolescents and adults).

a One dose of influenza vaccine per season is recommended for most persons. Children aged < 9 years who are receiving influenza vaccine for the first time or who received only one dose the previous season (if it was their first vaccination season) should receive two doses this season.

b Revaccination with meningococcal vaccine is recommended for previously vaccinated persons who remain at high risk for meningococcal disease (CDC, 2009).

c Bivalent HPV vaccine is approved for females aged 10–25 years. Quadrivalent HPV vaccine is approved for males and females aged 9–26 years.

d The minimum age for HPV-3 is based on the baseline minimum age for the first dose (i.e., 108 months) and the minimum interval of 24 weeks between the first and third doses. Dose 3 need not be repeated if it is administered at least 16 weeks after the first dose.

SOURCES: AAP, 2009; CDC, 2011b.

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2008. Bright Futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children and adolescents, 3rd ed. (J. F. Hagan, J. S. Shaw, and P. M. Duncan, eds.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP. 2009. Passive immunization. In Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 28th ed. (L. K. Pickering, C. J. Baker, D. W. Kimberlin, and S. S. Long, eds.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2009. Updated recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for revaccination of persons at prolonged increased risk for meningococcal disease. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 58(37):1042–1043.

CDC. 2011a. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/#about (accessed June 2, 2011).

CDC. 2011b. General recommendations on immunization—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recommendations and Reports: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(2):1–64.

Smith, J. C., D. E. Snider, and L. K. Pickering. 2009. Immunization policy development in the United States: The role of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Annals of Internal Medicine 150(1):W45–W49.

USPSTF (United States Preventive Services Task Force). 2008a. Grade definitions. Rockville, MD: United States Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm (accessed May 31, 2011).

USPSTF. 2008b. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force procedure manual. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf08/methods/procmanual.htm (accessed June 2, 2011).

USPSTF. 2010b. USPSTF A and B recommendations. Rockville, MD: United States Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsabrecs.htm (accessed June 2, 2011).

USPSTF. 2011. Methods and processes. Rockville, MD: United States Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/methods.htm (accessed May 21, 2011).