3

Existing Coverage Practices of National, State, and Private Health Plans

Before passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA), little standardization of the preventive services covered by both private and public payers existed. Historically, in the private sector, the extent of coverage for the preventive services that individuals receive and their exposure to out-of-pocket spending for these services have largely depended on the type of plan in which they are enrolled and the degree of cost sharing (including copayments and deductibles) that is part of the plan design. The passage of the ACA changed this variability by expanding federal requirements for plan benefits and limits on cost sharing for certain preventive services for private plans.

On September 23, 2010, the ACA preventive services requirements, detailed in Section 2713, went into effect. This section of the law adds to and amends the Public Health Services Act and the Employee Retirement Income Security Act and, as such, has jurisdiction over plans that are sold on the individual, small-group, and large-group markets by insurers as well as self-insured plans that are funded by employers.

These new rules require that private plans cover all United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Grade A and B recommendations, all vaccinations recommended by the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Bright Futures recommendations for children from the American Academy of Pediatrics (see Chapter 2) and the preventive services for women that will be informed by the deliberations of this Institute of Medicine committee and subsequently identified by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Therefore, for the first time in U.S. history, federal rules stipulate the preventive services that private plans must cover and prohibit out-of-pocket payments for individuals who obtain these covered services from in-network providers (Federal Register, 2010a; HHS, 2010). Only new plans or those plans that change are affected by these new requirements.1 Private plans that do not change their benefits or cost-sharing requirements are considered to be grandfathered and are not initially subject to the new requirements for the preventive services that must be covered.

HHS estimates that 78 million people enrolled in group plans and approximately 10 million people with individual policies will be subject to the prevention provisions in the ACA (HHS, 2010). These provisions will also apply to the plans that will be offered to consumers under the new state health insurance exchanges, although these exchanges and plans will not become operational until 2014.

This chapter reviews the policies and practices of private plans and publicly sponsored programs regarding the coverage before and after the enactment of the ACA of preventive services important to women. It describes the federal and state rules that are in effect today as well as identifies the types of plans or programs that will be affected by the new rules outlined in Section 2713 of the ACA.

RULES GOVERNING COVERAGE REQUIREMENTS BEFORE AND AFTER THE ACA

The coverage of preventive care provided under the individual and group markets and through self-funded employer health plans has been highly variable, differing by employer, insurer, and plan type. The Federal Employee Retirement and Income Security Act of 1974 regulates the coverage offered by self-insured or self-funded employer health plans as well as health insurance plans. An estimated 59 percent of covered workers are enrolled in self-insured group health plans (Claxton et al., 2010).

Federal Rules and Coverage Requirements

With few exceptions, federal rules do not specify what benefits plans must cover. The exceptions are that all self-funded employer health plans and health insurance issuers must offer coverage for a 48-hour hospital stay

_______________

1 Plans will lose their “grandfather” status if, compared to March 23, 2010, they significantly cut or reduce benefits, raise co-insurance charges or significantly raise co-payment charges or deductibles, significantly reduce employer contributions, tighten annual limits on what insurers will pay, or change insurers. Plans that make any of these changes can be deemed to lose their grandfather status and will be required to follow the ACA preventive benefit coverage rules (Federal Register, 2010b).

after a vaginal delivery or a 96-hour stay after a delivery by cesarean section if they cover maternity care; mental health parity, which affects mental health care benefits and benefits for the treatment of substance use disorders; and benefits for breast reconstruction after a mastectomy and treatment of surgical complications for health plans that cover mastectomies.

In addition, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-555), which amended Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, requires that employers with 15 or more employees treat women who are pregnant or affected by pregnancy-related conditions in the same manner that employers treat other workers or applicants. It requires that “any health insurance provided by an employer must cover expenses for pregnancy-related conditions on the same basis as costs for other medical conditions.” An employer is “not required to provide health insurance for expenses arising from abortion, except where the life of the mother is endangered” (95th U.S. Congress, 1978). These payments must be paid for exactly like other medical conditions; and no additional, increased, or larger deductible can be imposed. Moreover, employers must provide the same level of health benefits for spouses of male employees as they do for spouses of female employees (95th U.S. Congress, 1978).

In 2000, a ruling by Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) found that employers that offered plans that provided coverage for drugs, devices, and preventive care but that did not include coverage for preventive contraceptives to be in violation of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (EEOC, 2000). Although this ruling was upheld by a federal district court in the state of Washington (Erickson v. Bartell Drug Co.), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit (No. 06-1706, 2007 WL 763842) ruled in a 2-to-1 decision that an employer may exclude contraception coverage from its health plan without violating the Pregnancy Discrimination Act because the employer also failed to cover condoms and vasectomies that affect men (2007). Despite this ruling, the EEOC finding still stands, and the vast majority of health plans cover contraceptives, and in 2002, more than 89 percent of insurance plans covered contraceptive methods (Sonfield et al., 2004). A more recent (2010) survey of employers found that 85 percent of large employers and 62 percent of small employers covered Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives (Claxton et al., 2010).

The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 permits individuals enrolled in high-deductible health plans to make tax-favored contributions to health savings accounts (HSAs). These plans may provide preventive care benefits without a deductible or with a separate deductible below the minimum plan deductible. In 2010, 93 percent of high-deductible health plans with HSAs covered preventive services without having to meet the deductible (Claxton et al., 2010). In 2004, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) issued a bulletin that identified certain

TABLE 3-1 IRS-Defined Preventive Care Screening Services

|

|

|

|

Preventive Care Screening Services |

|

|

|

|

|

Cancer Breast cancer (e.g., mammogram) Cervical cancer (e.g., Pap smear) Colorectal cancer Prostate cancer (e.g., prostate-specific antigen test) Skin cancer Oral cancer Ovarian cancer Testicular cancer Thyroid cancer Heart and Vascular Diseases Abdominal aortic aneurysm Carotid artery stenosis Coronary heart disease Hemoglobinopathies Hypertension Lipid disorders Infectious Diseases Bacteriuria Chlamydial infection Gonorrhea Hepatitis B virus infection Hepatitis C Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection Syphilis Tuberculosis Mental Health Conditions and Substance Abuse Dementia Depression Drug abuse Problem drinking Suicide risk Family violence |

Metabolic, Nutritional, and Endocrine Conditions Anemia, iron deficiency Dental and periodontal disease Diabetes mellitus Obesity in adults Thyroid disease Musculoskeletal Disorders Osteoporosis Obstetric and Gynecologic Conditions Bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy Gestational diabetes mellitus Home uterine activity monitoring Neural tube defects Preeclampsia Rh incompatibility Rubella Ultrasonography in pregnancy Pediatric Conditions Child developmental delay Congenital hypothyroidism Lead levels in childhood and pregnancy Phenylketonuria Scoliosis, adolescent idiopathic Vision and hearing disorders Glaucoma Hearing impairment in older adults Newborn hearing |

|

|

|

NOTE: Services that are important to women as well as those that disproportionately or differentially affect women are indicated by boldface italic type.

preventive services that are allowed to be included in these plans, which include, but are not limited to, the services listed in Table 3-1.

SOURCE: IRS, 2004.

State Coverage Requirements

The business of insurance is regulated at the state level, and state requirements for the preventive services that health plans must cover vary

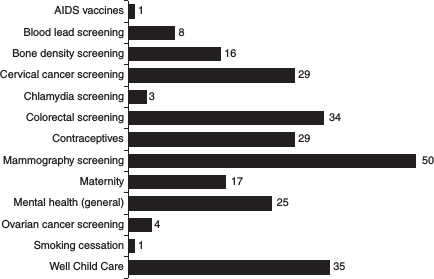

FIGURE 3-1 State-mandated preventive benefits of importance to adult women, 2010.

SOURCE: BlueCross BlueShield Association, 2010.

considerably (Figure 3-1).2 In recent years, state lawmakers have enacted a wide range of mandates for different types of health care services. The reach of these benefit mandates is limited, however, as they apply only to insurance plans that are sold to employers and individuals in the state and do not apply to self-funded employer health plans, which are plans that provide coverage for the majority of the employer’s workers and their dependents.

All states, with the exception of Utah, require plans to cover mammography screening, 29 states require coverage of cervical cancer, and 29 require coverage of contraception (Bluecross Blueshield Association, 2010). Far fewer states require bone density screening (16 states), maternity care (17 states in the case of the individual market), and screening for chlamydia infection (3 states). It also worth noting that some states require coverage for preventive services that do not yet exist, such as an AIDS vaccine and ovarian cancer screening.

_______________

2 Many different organizations collect this information, including the BlueCross BlueShield Association, the National Association of Health Commissioners, the Council for Affordable Health Insurance, and the National Conference of State Legislatures. Figure 3-1 is presented to show the variability in coverage by state rather than an exact count of the laws that states currently have in place.

How these mandates are structured also differ substantially. For example, they can be legislated to affect the benefits that different types of insurance markets (small- or large-group plans or the individual market) must cover, what they must offer to sell (but not necessarily cover), the type of plan that is included (e.g., health maintenance organizations [HMOs]), the target populations for the service, and the periodicity of the service. Many, but not all, of these benefits are now covered under the new ACA preventive coverage rules without any cost sharing. Nevertheless, the ACA preventive care rules do not supersede state requirements. This means that for states that have coverage mandates for preventive services that are broader than the list of services required to be covered by Section 2713 of the ACA, insurance plans that sell policies in those states must still offer coverage for those services, in addition to the services required by the ACA.3

Although many states have coverage mandates or specific benefit requirements, 12 states have also required plans that sell on the individual and small-group markets to offer standardized benefit packages (KFF, 2009b). These standardized policies generally include a class of services and outline cost-sharing requirements. They were intended to facilitate the comparison of different plans for consumers and to make it harder for insurers to design benefit packages that are attractive to healthy individuals and avoid drawing those with health problems. In most states, insurers must offer the standardized plans but can also sell other types of plans (KFF, 2009b).

The benefit package that the commonwealth of Massachusetts requires, however, is a notable exception and does provide detailed coverage information. In 2006, the commonwealth of Massachusetts passed Chapter 58, the health reform law. This law combines the concept of individual responsibility through an individual mandate, which requires that individuals purchase health insurance that meets minimum standards developed by the state (creditable coverage). To ensure affordability, however, government subsidies are provided. This law created multiple public and private health insurance pathways and initiated a system of shared responsibility among the stakeholders in health care provision. Chapter 58 also created a health insurance exchange, known as the Commonwealth Connector, to make health coverage available to residents and to regulate the insurance products offered through the exchange to ensure that individuals have minimum creditable coverage. The reforms enacted by the commonwealth of Massachusetts served as a model for the ACA.

_______________

3 When the federal subsidies for individuals to purchase coverage through the insurance exchanges become available, the costs of any benefits mandated by the states that exceed those specified in federal law will have to be funded by the states for those receiving subsidies. Given this new cost, it is possible that some states will eliminate these mandated benefits, at least in the individual market.

Although the overall rate of insurance coverage in Massachusetts before passage of the legislation exceeded 90 percent, since enactment, numerous subgroups of women have experienced substantial gains in coverage. In particularly, ethnic and racial minorities, low-income women, women without dependent children, and nonelderly women aged 50 to 64 years have experienced substantial gains in coverage, such that coverage is nearly universal for these subgroups of women (Long et al., 2010).

The preventive services benefits for women that plans must offer to be considered to have minimum creditable coverage are based on the recommendations for adults issued by the Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (MHQP) and other nationally recognized guidelines (Hyams and Cohen, 2010; MHQP, 2007). MHQP recommendations closely mirror those of the USPSTF but also include the coverage of preventive services such as counseling for preconception and menopause management and treatment for menopause.

According to the ACA, the new coverage rules for private plans in Massachusetts will be subject to the requirements of Section 2713, although the coverage may be broader than that included in the state law.4 In addition, the Chapter 58 rules state that plans must cover at least three preventive visits without applying the costs for those visits to the deductible (but copayments may exist) and require that contraceptive services and supplies be covered as preventive services without cost sharing.

Private Insurance Coverage Practices

Detailed information on the coverage and benefits provided by private insurance plans and employers and on the scope of the preventive benefits that they cover is often proprietary and difficult to obtain. This information is enormously complex, and details about the coverage provided differ considerably from plan to plan and employer to employer. Although periodic surveys of employers of the health care benefits that they cover and reviews of documents that summarize the plans are performed, most surveys and reviews look at classes of services rather than the actual specific benefits provided.

In addition, research on this topic suffers from other limitations. The research is often conducted by researchers who are either funded by or who are employees of health plans or employer groups; the response rates for these surveys are usually low; and the respondents, who are typically employers, may not know the specific details about benefit coverage included

_______________

4 Grandfathered plans, including those sold through the Commonwealth Connector, will not be subject to the new requirements unless and until they lose the grandfathered status discussed earlier.

in the plans that they have purchased. The following section highlights some of this research to provide some insights into the level of coverage and services provided by the private insurance sector but does not provide information on how plans and employers address cost sharing, copayments, and coinsurance for these specific services.

Employer-Based Health Plans

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ ongoing National Compensation Survey (DOL, 2011) surveyed approximately 3,900 employers with the aim of providing comprehensive data on employment-based health care benefits. A supplemental analysis of approximately 3,200 plan documents, including summary descriptions of the plans and other short summaries or comparison charts, was conducted to look at the extent of coverage of certain health benefits. When coverage or exclusion of a specific benefit by a plan is specifically mentioned, it is noted. For many of the benefits reviewed, coverage for particular services was mentioned one way or the other, but it is possible that the services would be covered for the workers.

The data on preventive care are limited but indicate that 56 percent of participants were in plans that identified coverage for adult immunizations and inoculations, 80 percent were in plans that covered adult physical examinations, and 77 percent were in plans that covered well-baby care. Gynecological examinations and services, such as pelvic examinations and Pap smears were covered for 60 percent of participants of employer-based health plans, usually under headings such as “well-woman exams.” However, these services were often subject to plan or separate limits, and copayments were commonly required. Plans often limited the number of examinations per year and the dollar amount on the services covered during examinations.

Sterilization was not mentioned in the coverage documents for the employer-based health plans of more than 70 percent of participants. However, when it was mentioned, approximately 90 percent of participants were in plans that cover sterilization. Coverage for maternity care was also not uniformly identified by the plans. Sixty-six percent of workers were in plans that explicitly covered maternity care, and only 6 percent of the workers in those plans had these benefits in full (virtually all of the remaining third of workers were in plans that did not specifically mention coverage for maternity care).

In 2001, Mercer Human Resource Consulting Inc. conducted the National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans, which had a special supplement on preventive care. More than 2,000 employers providing benefits to their employees completed the survey. The response rate was 21 percent. The survey uncovered significant differences in the preventive services covered. These differences were related to employer size, incentives, and extent of coverage (Bondi et al., 2006). Because only one-fifth of

employers offered their workers a choice of more than one plan, examination of the rates of coverage of clinical preventive services in the employer’s primary plans provides the best summary of the ranges of rates of coverage for different services: 75 percent covered physical examinations, 74 percent covered gynecological examinations, 57 percent covered cholesterol screenings, and only 37 percent covered screening for Chlamydia infection.

For women, primary employer-based health plans covered breast cancer and cervical cancer screening at rates of 80 and 79 percent, respectively. Lifestyle modification services were covered at much lower rates, with nutritional counseling covered by 17 percent of primary plans, weight loss and management counseling was covered by 15 percent, physical activity counseling was covered by 13 percent, alcohol problem prevention was covered by 18 percent, and any kind of tobacco cessation service was covered by 20 percent.

Approximately half of all large employers required that their plans cover clinical preventive services, whereas only 17 percent of small employers had the same requirement. Small employers were also less likely to offer coverage of clinical preventive services and lifestyle modification services, although the differences were not large.

Large employers were far more likely than small employers to offer financial incentives to employees to use clinical preventive services. However, small employers offered flexible scheduling or time off to access preventive services much more often than large employers did. Lifestyle modification services, such as physical activity counseling and weight loss management, were covered the least often, regardless of employer size.

The National Business Group on Health conducted a comprehensive analysis and synthesis of a wide range of clinical preventive services and their impacts on disease prevention and early detection of health conditions and disease according to both health and economic measures (NBGH, 2009). On the basis of their analyses, they compiled a purchaser’s guide that recommends 46 clinical preventive services that should be included in employer health benefit plans. Benefits directly relevant to women are summarized in Box 3-1.

Individual Insurance Plans

As with the small- and large-group insurance markets, the individual insurance market appears to have considerable variability in coverage of preventive services. In a 2006–2007 survey of individual insurance plans conducted by American’s Health Insurance Plans, the trade association for health insurers in the United States (AHIP, 2007), coverage levels were found to vary considerably by type of plan, with all HMO plans responding to the survey indicating that they covered physical examinations for adults, annual visits to an obstetrician-gynecologist, and cancer screening; but far

BOX 3-1

National Business Group on Health’s Recommended

Benefits Directly Relevant to Women

Breast Cancer: Breast cancer screening should include clinical breast examination and an annual mammography (for women from ages 40 to 80 years and for younger women, if it was deemed medically indicated), assessment of a woman’s genetic risk for breast cancer and testing for mutations in the BRCA breast cancer-associated gene for women at high risk, counseling, and preventive medication and treatment (i.e., tamoxifen) for women with a high risk of breast cancer or surgical removal of the breasts or ovaries.

Cervical Cancer: The purchaser’s guide recommends coverage of conventional Pap smears. Plans are to use their own discretion on coverage for newer screening methods, including liquid-based, thin-layer preparations, computer-assisted screening, and tests for human papillomavirus infection for women beginning at age 21 years or within 3 years of onset of sexual activity through age 65 years and beyond for high-risk women. The guidelines recommends coverage for screening services at least once every three years and not more than once a year.

Contraceptive Use: The guidelines recommend coverage for counseling on contraceptive use at least once a year and when emergency contraception is provided for all beneficiaries aged 13 to 55 years. They also recommend coverage of the full range of Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives, including all hormonal medications, contraceptive devices, and voluntary sterilization.

Osteoporosis: The guidelines recommend screening and treatment for osteoporosis starting at age 65 years for women with a normal risk. High-risk women are eligible at age 60 years or earlier, if it is medically indicated, and not more than once every two calendar years. The screening tools recommended for coverage include the Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument and the Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation tool, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, peripheral dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, peripheral quantitative computed tomography, radiographic absorptiometry, single-energy absorptiometry, and ultrasound. All Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for osteoporosis are covered for beneficiaries age 60 years and older who meet medical necessity criteria.

Pregnancy: Pregnant women should receive screening and counseling (up to eight interventions per calendar year) for alcohol misuse during pregnancy; urine culture for asymptomatic bacteriuria at between 12 and 16 weeks of gestation and subsequently as medically indicated; structured breastfeeding education and behavioral counseling for all pregnant and lactating women (in office, in the hospital, or at home after birth), without a limit on the number of sessions, provided that care is medically necessary; folic acid counseling and supplements; screening and medication for group B streptococcal disease; screening for hepatitis B virus infection and immunizations against hepatitis B virus; screening, counseling, and preventive medication for human immunodeficiency virus; influenza immunizations; screening for preeclampsia; prenatal screening and testing for neural tube defects (for all women at elevated risk) and chromosomal abnormalities (for all women aged 35 years and older), including, but not limited to amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling, and ultrasound; Rh (D) blood typing and antibody and immunoglobulin testing; screening for rubella and syphilis; tetanus immuniza-

tion; screening and treatment (counseling) for tobacco use; and screening, counseling, and treatment for hypertension.

Sexually Transmitted Infections: The guidelines recommend coverage for counseling to prevent sexually transmitted infections for all adolescents and adults. They also recommend screening for chlamydia infection and gonorrhea for all women aged 25 years and younger (and for older women, if it is medically indicated); screening and counseling for human immunodeficiency virus infection for all people aged 13 to 64 years; and an annual screening (and screening more frequently, if needed) for syphilis for all beneficiaries at risk of infection.

SOURCE: NBGH, 2009.

fewer HMOs covered contraceptives (39 percent for HMO plans for single individuals and 59 percent for HMO plans for families).

Coverage rates were lower for preferred provider organizations (PPOs) and point-of-service (POS) plans as well as high-deductible plans with HSAs or medical savings accounts (MSAs). The rate of coverage for physical examinations for adults ranged from 66 percent for PPO or POS plans for single individuals to 75 percent of plans with HSAs or MSAs for families. The rate of coverage for annual visits to an obstetrician-gynecologist was higher, ranging from a low of 82 percent for plans with HSAs and MSAs for families to a high of 96 percent for PPOs and POS plans for single individuals. Rates of coverage for cancer screenings ranged from 81 percent for HSAs and MSAs for families to 94 percent for PPOs and POS plans for single individuals. Coverage rates for oral contraceptives were also lower, ranging from 39 percent for HMOs for single individuals to 79 percent for PPOs and POS plans for single individuals.

Federal Employees Health Benefits Program

Millions of federal workers and their dependents receive their health insurance coverage through the Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) program. The FEHB program purchases health insurance coverage through private plans for federal workers and their dependents. The preventive ser-

vices covered, provider networks, and out-of-pocket spending responsibilities for these private plans vary by state. According to the ACA, plans that are offered under the FEHB program either are or will be required to offer coverage of all services that are recommended by the USPSTF, the ACIP, and Bright Futures. The plans offered under the FEHB program either are or will be required to offer coverage for preventive services for women without cost sharing if the services are obtained from an in-network provider. In addition, since 1999, almost all FEHB program plans are required to cover all Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptive supplies and devices (OPM, 1998).

Public-Sector Programs

The federal and state governments provide health coverage to a sizable share of the U.S. population through a wide range of programs. Nearly all seniors have primary coverage through Medicare, the federal program for those aged 65 years and over and individuals with permanent disabilities. In 2010, more than 66 million low-income individuals were covered by Medicaid, the federal-state program for low-income parents, children, seniors, and people with disabilities (MACPAC, 2011). The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provided health care services to 5.3 million veterans and their families in 2008 (VA, 2011a); and TRICARE, the health care plan for the U.S. military, serves millions of individuals in active-duty military service and their dependents, military retirees and their families, and other beneficiaries from any of the seven services. The Indian Health Service (IHS) covers nearly 2 million American Indians and Alaska Natives (IHS, 2011).

Although the ACA contains new rules for Medicare coverage of preventive services for beneficiaries and incentives for Medicaid to cover preventive services without cost sharing, the preventive services requirements that are promulgated under Section 2713 affect only private plans. The rules in Section 2713 only amend and add to the Public Health Services Act and the Federal Employee Retirement and Income Security Act and therefore do not affect the coverage offered by military health care programs, such as TRICARE and VA program, or the IHS. It is useful, however, to understand how these different programs have handled policies for coverage of preventive services important to women. These policies are detailed in the following sections.

Medicare

Medicare provides health care coverage for about 39 million seniors and 8 million people under age 65 years with permanent disabilities (KFF, 2010). About 56 percent of Medicare beneficiaries are women (KFF, 2009a).

Sections of the ACA other than those related to Medicare make many changes to the covered preventive services that are important to female Medicare beneficiaries. Before passage of the ACA, many preventive benefits important to women’s health, such as mammography, clinical breast examinations, bone density tests, Pap smears, and pelvic examinations, were covered but required a 20 percent copayment; that is, Medicare covered only 80 percent of the full cost of these tests. The ACA requires that all Medicare beneficiaries receive coverage without copayments for those services that receive Grade A or B recommendations from the USPSTF, as well as coverage for all vaccines recommended by ACIP (111th U.S. Congress, 2010). This rule became effective on January 1, 2011.

All new Medicare beneficiaries have been eligible to receive a “welcome to Medicare” visit that is similar in scope to a wellness visit. The ACA broadened this benefit for beneficiaries to include a new annual wellness examination for all beneficiaries with no copayment (111th U.S. Congress, 2010). At this visit, the medical and family health histories are reviewed, basic health measurements are taken, a screening for the preventive services required is performed, and risk factors and treatment options are identified.

Although Medicare is typically considered a program for seniors, a sizable share of Medicare beneficiaries are nonelderly and qualify on the basis of a permanent disability. In 2009, about 850,000 disabled women under age 45 years were enrolled in Medicare (CMS, 2010). Women Medicare beneficiaries in this age group have reproductive health care needs but do not get coverage for contraceptive services or devices through Medicare Part A or B. They may get coverage, however, for oral contraceptive pills through their Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage. The extent of their out-of-pocket costs and the scope of coverage for prescriptions are largely dependent on the type of Part D drug plan that they select.

A growing share of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in managed care arrangements through Medicare Advantage plans. These plans can be more flexible in the types of benefits that they cover. Some cover services that are not part of the traditional Medicare benefit package, such as contraceptives, although the federal government has no requirement to cover such things. Medicare does not cover sterilization when it is not part of a necessary treatment for an illness or injury, nor would any payment be made for sterilization as a preventive measure. This includes the case when a primary care provider believes that pregnancy would cause overall endangerment to a woman’s health or psychological well-being (CMS, 2011).

Medicaid

Medicaid, a program for certain low-income Americans jointly financed and operated by state and federal governments, offers coverage for many preventive services. Approximately 66 million individuals were covered by

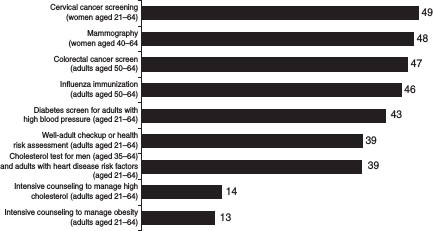

Medicaid in 2010 (MACPAC, 2011). An estimated 30 million children in the United States are insured by Medicaid (KFF, 2011b), and it provides coverage for 40 percent of all births in the United States (Wier et al., 2010). With the exception of mandatory coverage for smoking cessation with no cost sharing for pregnant women (Section 4107), the ACA does not require that Medicaid cover preventive services with or without cost sharing. Rather, it includes an incentive for states to cover the services in the form of an increased 1 percent matching federal payment for these services to states that provide the recommended preventive services without cost sharing to their beneficiaries (Section 4106) (111th U.S. Congress, 2010). Figure 3-2 shows the numbers of states offering coverage for preventive services through Medicaid.

Today, Medicaid coverage of preventive services depends on the enrollees’ age and state of residence. For children under age 21 years, the scope of coverage is comprehensive as a result of the Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment Program. This mandatory program requires that

FIGURE 3-2 Number of state Medicaid programs that reported covering certain recommended preventive services for adults and health risk assessments or well-adult checkups. Although the USPSTF does not explicitly recommend well-adult checkups or health risk assessments for adults, such health care visits provide an opportunity to deliver recommended preventive services, such as blood pressure tests and obesity screenings. The data do not include the numbers for states that reported that a service is covered under the managed care program but not under the fee-for-service program.

SOURCE: Government Accountability Office analysis of survey of state Medicaid directors conducted between October 2008 and February 2009.

state Medicaid programs cover screening and diagnostic services, as well as the treatments needed to correct or improve the problems identified by the screening and diagnostic services. For children, the screening and preventive services typically include well-child visits, vision and dental screenings, and immunizations (CMS, 2005). State Medicaid programs are not permitted to charge cost sharing for services provided to children and pregnant women but may charge other eligible populations a nominal fee (SSA, 2011c).

For adults participating in Medicaid, preventive services are generally covered according to the recommendations of each state, but the preventive services for adults that the states cover vary considerably (GAO, 2009). For example, services such as cervical cancer screening and mammography were covered by nearly all state Medicaid programs, but far fewer states covered well-adult checkups or cholesterol tests (GAO, 2009). Coverage of screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections is also typically included in almost all state Medicaid programs (Ranji et al., 2009a).

Family planning services, in contrast, are federally required for all states that participate in Medicaid. Since 1972, state Medicaid programs have been required to cover “family planning services and supplies furnished (directly or under arrangements with others) to individuals of childbearing age (including minors who can be considered to be sexually active), who are eligible under the State plan, and who desire such services and supplies” (SSA, 2011a). These services must be provided without cost sharing. In return, states receive a 90 percent federal match on the funds that they spend on these services (SSA, 2011b). All states provide coverage for family planning services and prescription contraceptive supplies, although coverage of nonprescription contraceptives, such as condoms and emergency contraceptives, and sterilization varies considerably from state to state (Ranji et al., 2009a).

Coverage of preconception counseling and other elements of preconception care are optional for state Medicaid programs and, as a result, are not as universally covered as contraceptives. Of the 44 states that responded to a 2008 Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation survey, only 26 covered preconception counseling for women enrolled in Medicaid (Ranji et al., 2009a).

Medicaid is the largest payer of maternity services in the nation and provides coverage of a comprehensive range of pregnancy-related services for low-income women who qualify. These services, however, vary considerably from state to state. For example, in 2008, 24 out of 44 states responding to a national survey covered genetic counseling and 39 covered nutrition counseling and psychosocial counseling (Ranji et al., 2009b). Similarly, coverage of breastfeeding support services is also an optional Medicaid benefit and is more limited. Twenty-five of the 44 surveyed states covered breastfeeding education services, 15 states covered lactation con

sultations, and 31 states covered breast pump rentals. Eight states did not cover any breastfeeding support services for women enrolled in Medicaid (Ranji et al., 2009b).

Children’s Health Insurance Program

For low-income children whose family incomes exceed Medicaid eligibility levels, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) provides insurance coverage at generally affordable costs. Established in 1997, this federal block grant program to states provides state and federal funds to extend insurance coverage to low-income children. Each state may expand coverage by raising Medicaid income eligibility levels for families with children, establishing a separate state program, or designing a combination of the two approaches. In 2010, an estimated 7.7 million children and 347,000 parents and pregnant women who did not qualify for Medicaid were enrolled in CHIP at some point during the year (MACPAC, 2011).

CHIPs are prohibited from imposing cost sharing for well-baby and well-child care, including immunizations. Children who are covered through a CHIP Medicaid expansion option receive the same benefits as children who are covered through Medicaid. However, considerable variation in the scope of covered preventive services exists among the states, which operate separate programs. A 2001 review of CHIP coverage of reproductive health services conducted by the Guttmacher Institute found that of the 29 states that operated separate state programs, 16 specifically identified that family planning services and supplies were covered and most of the remaining plans covered these services through the general category “prenatal care and prepregnancy family planning services” (Gold and Sonfield, 2001). Most states also covered screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections.

The 2008 CHIP Reauthorization Act made it easier for states to extend CHIP to cover pregnancy-related services through CHIP, and 18 states have done this either through extending eligibility to pregnant women or through a new option to extend eligibility to “unborn children” (KFF, 2011a). Like Medicaid, coverage for pregnant women under CHIP typically ends at 60 days postpartum. States that cover this group of women through the Medicaid expansion use Medicaid benefit rules.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care Services

The rising enlistment of women in active-duty military services has led to the growth in the numbers of women receiving care through VA. According to VA, women make up approximately 1.8 million of the nation’s

23 million veterans and account for nearly 5.5 percent of veterans who use VA health care services (VA, 2011b).

The scope of care offered to women veterans is broad and includes the following preventive services important to women: health evaluation and counseling, disease prevention, nutrition counseling, weight control, smoking cessation, and substance abuse counseling and treatment, as well as gender-specific primary care, including Pap smears, mammogram, birth control, preconception counseling, human papillomavirus vaccine, and menopausal support (hormone replacement therapy). In addition, women receive coverage for “mental health, including evaluation and assistance for issues such as depression, mood, and anxiety disorders; intimate partner and domestic violence; sexual trauma; elder abuse or neglect; parenting and anger management; marital, caregiver, or family-related stress; and post-deployment adjustment or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)” (VA, 2011b).

TRICARE

The U.S. Department of Defense operates TRICARE, a managed health care program for active-duty members of the military, families of active-duty service members, retirees and their families, and other beneficiaries from any of the seven services (TRICARE, 2011). Depending on their level of service, enrollees can choose from different coverage plans that have the same benefits but different provider networks and out-of-pocket spending requirements. TRICARE covers a broad range of preventive services for women enrollees, including contraceptive supplies, services, and sterilization; mammograms and physical breast examinations; counseling; maternity care; Pap smears (including human papillomavirus testing); and genetic testing.

Indian Health Service

American Indians and Alaska Natives who are members of federally recognized tribes are eligible to receive health care services without cost sharing though the IHS, which operates health care facilities on or near Indian reservations. Although a wide range of “health promotion and disease prevention services” (LII, 2010) are specified, the availability of the actual services for those using IHS services varies tremendously from region to region. Health promotion services whose provision is defined by Title 25 of the U.S. Code include smoking cessation, reduction in alcohol and drug misuse, improvement in nutrition, improvement in physical fitness, family planning, stress control, and pregnancy and infant care (including fetal alcohol syndrome prevention). The disease prevention services covered

under Title 25 include immunizations, control of high blood pressure, control of sexually transmitted diseases, prevention and control of diabetes, control of toxic agents, occupational safety and health, accident prevention, fluoridation of water, and control of infectious agents (LII, 2010). Screening mammography is also included as a covered benefit for women.

Growing attention to the importance of preventive care in both federal- and state-supported and private-sector plans has been seen in recent years. Despite this attention, coverage of preventive services in both the private and public sectors is uneven at best. Heavy reliance has been placed on the clinical guidance promulgated by the USPTSF, but adoption of the full range of services is still not the norm. Some programs and plans have provided more limited coverage, whereas others are broader in scope, providing coverage for preventive services like preconception counseling, contraceptive services and supplies, and well-woman visits, despite their absence from these recommendations. The ACA requirements will make important strides in ensuring that most Americans have coverage for the full range of recommended preventive services.

AHIP (America’s Health Insurance Plans). 2007. Individual health insurance 2006–2007: A comprehensive survey of premiums, availability and benefits. Washington, DC: Center for Policy and Research, America’s Health Insurance Plans.

BlueCross BlueShield Association. 2010. State legislative healthcare and insurance issues: 2010 Survey of Plans. Office of Policy and Representation, BlueCross Blue Shield Association.

Bondi, M. A., J. R. Harris, D. Atkins, M. E. French, and B. Umland. 2006. Employer coverage of clinical preventive services in the United States. American Journal of Health Promotion 20(3):214–222.

Claxton, C., B. DiJulio, B. Finder, J. Lundy, M. McHugh, A. Osei-Anto, H. Whitmore, J. Pickreign, and J. Gabel. 2010. Employer health benefits 2010 annual survey, 2010. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research & Educational Trust http://ehbs.kff.org/pdf/2010/8085.pdf.

CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). 2005. Medicaid early and periodic screening and diagnostic treatment benefit. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. http://www.cms.gov/medicaidearlyperiodscrn/02_Benefits.asp#TopOfPage (accessed May 14, 2011).

CMS. 2010. 2010 CMS data compendium, Table IV.2. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. http://www.cms.gov/DataCompendium/14_2010_Data_Compendium.asp#TopOfPage (accessed May 11, 2011).

CMS. 2011 CMS coverage database. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/ (accessed May 11, 2011).

DOL (U.S. Department of Labor). 2011. Selected medical benefits: A report from the Department of Labor to the Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor.

EEOC (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission). 2000. Decision on coverage of contraception. Washington, DC: Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Federal Register. 2010a. Interim final rules for group health plans and health insurance issuers relating to coverage of preventive services under the patient protection and affordable care act. Federal Register 75(137):41726–41730.

Federal Register. 2010b. Interim final rules for group health plans and health insurance coverage relating to status as a grandfathered health plan under the patient protection and affordable care act. Federal Register 75(116):34538–34570.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2009. Medicaid preventive services: Concerted efforts needed to ensure beneficiaries receive services. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

Gold, R. B., and A. Sonfield. 2001. Reproductive health services for adolescents under the state children’s health insurance program. Family Planning Perspectives 33(2):81–87.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2010. Preventive regulations. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.healthcare.gov/center/regulations/prevention/regs.html (accessed April 13, 2011).

Hyams, T., and L. Cohen. 2010. Massachusetts health reform: Impact on women’s health. Boston, MA: Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

IHS (Indian Health Services). 2011. IHS Year 2011 Profile. Washington, DC: Indian Health Service. http://www.ihs.gov/publicAffairs/IHSBrochure/profile2010.asp (accessed May 25, 2011).

IRS (Internal Revenue Service). 2004. Health savings accounts—Preventive care. Washington, DC: Internal Revenue Service.

KFF (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation). 2009a. Medicare’s role for women. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://www.kff.org/womenshealth/upload/7913.pdf (accessed May 10, 2011).

KFF. 2009b. Standardized plans in the individual market, as of March 2009. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparereport.jsp?rep=6&cat=7 (accessed May 15, 2011).

KFF. 2010. Medicare chartbook, 4th ed. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://facts.kff.org/chart.aspx?cb=58&sctn=162&ch=1714 (accessed May 10, 2011).

KFF. 2011a. Where are states today? Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children and non-disabled adults. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

KFF. 2011b. Health coverage of children: The role of Medicaid and CHIP. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

LII (Legal Information Institute). 2010. U.S. Code, Title 25: Indians. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Law School. http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/uscode25/usc_sup_01_25.html (accessed May 10, 2011).

Long, S., K. Stockey, L. Birchfield, and S. Shulman. 2010. The impact of health reform on health insurance coverage and health care access, use and affordability for women in Massachusetts. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute and the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation. http://masshealthpolicyforum.brandeis.edu/forums/Documents/Issue%20Brief_UrbanBCBSMAF.pdf (accessed May 10, 2011).

MACPAC (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission). 2011. Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP. Washington, DC: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.

MHQP (Massachusetts Health Quality Partners). 2007. Adult routine preventive care recommendations 2007/8. Watertown, MA: Massachusetts Health Quality Partners.

NBGH (National Business Group on Health). 2009. A purchaser’s guide to clinical preventive services: Moving science into coverage. Washington, DC: National Business Group on Health.

OPM (Office of Personnel Management, Retirement and Insurance Service). 1998. Benefits administration letter 98-418. Washington, DC: Office of Personnel Management, Retirement and Insurance Service. http://www.opm.gov/retire/pubs/bals/1998/98-418.pdf (accessed May 10, 2011).

Ranji, U., A. Salganicoff, A. Stewart, M. Cox, and L. Doamekpor. 2009a. State Medicaid coverage of family planning services: Summary of state survey findings. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services. http://www.kff.org/womenshealth/upload/8015.pdf (accessed May 10, 2011).

Ranji, U., A. Salganicoff, A. Stewart, M. Cox, and L. Doamekpor. 2009b. State Medicaid coverage of perinatal services: Summary of state findings. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services. http://www.kff.org/womenshealth/upload/8014.pdf (accessed May 10, 2011).

SSA (U.S. Social Security Administration). 2011a. Social Security Act—Definitions, Sec. 1905. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Social Security Administration. http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title19/1905.htm (accessed May 10, 2011).

SSA. 2011b. Social Security Act—Definitions, Sec. 1903. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Social Security Administration. http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title19/1903.htm (accessed May 10, 2011).

SSA. 2011c. Social Security Act—State option for alternative premiums and cost-sharing, Sec. 1916A. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Social Security Administration. http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title19/1916A.htm (accessed May 10, 2011).

Sonfield, A., R. B. Gold, J. J. Frost, and J. E. Darroch. 2004. U.S. insurance coverage of contraceptives and the impact of contraceptive coverage mandates, 2002. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 36(2):72–79.

TRICARE. 2011. Covered services. Falls Church, VA: U.S. Department of Defense. http://www.tricare.mil/mybenefit/jsp/Medical/IsItCovered.do?topic=Women)%20 (accessed May 10, 2011).

United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. 2007. In re Union Pacific Railroad Employment Practices Litigation. No. 06-1706. 2007 WL 763842.

95th U.S. Congress. 1978. Public Law 95-555. Washington, DC: U.S. Congress.

111th U.S. Congress. 2010. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act health-related portions of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Congress.

VA (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs). 2011a. Number of veteran patients by healthcare priority group: FY 2000 to FY 2009. Washington, DC: National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2011b. Women veterans health care. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/womenshealth/ (accessed April 15, 2011).

Wier, L. M., K. Levit, E. Stranges, K. Rayn, A. Pfuntner, R. Vandivort, P. Santora, P. Owens, C. Stocks, and A. Elixhauser. 2010. HCUP facts and figures: Statistics on hospital-based care in the United States, 2008. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.hcupdoc.net/reports/factsandfigures/2008/pdfs/FF_report_2008.pdf (accessed May 15, 2011).