State Experiences with Defining a Minimum Benefit Standard

Some states, including Massachusetts, Maryland, and Utah, have state-specific approaches to defining minimum benefit packages for the individual and employer markets that may provide important lessons for defining essential health benefits. Economist Dr. Jonathan Gruber discussed the economic principles underlying definition of benefits and described lessons from Massachusetts’ experience with health reform. These lessons were expanded upon by Dr. Jon Kingsdale, formerly of the Massachusetts Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority. Then, Drs. Beth Sammis and Rex Cowdry of the Maryland Insurance Administration (MIA) and Health Care Commission (HCC), respectively, described Maryland’s process for developing a “standard benefit plan” in the mid-1990s. Next, Representative James Dunnigan of the Utah State House of Representatives and, finally, Mr. Matt Salo of the National Governors Association (NGA) urged the committee to recognize the need for state flexibility in definition and implementation.

As a founding member of the Massachusetts Health Insurance Connector Authority Board, and as an advisor to Congress and the Obama administration during the development of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), Dr. Gruber focused on the tradeoffs inherent in developing the essential health benefits (EHB) package: generosity of coverage, affordability of coverage, and minimizing disruption from current insurance status.

Generosity of Coverage

Dr. Gruber noted that “we would all like to include the benefits we think are part of a real and generous insurance package.” Despite this desire for generosity, to ensure affordability, coverage is subject to (1) specified categories of care, (2) limitations, and (3) cost sharing.

Categories of Covered Benefits

The list of the essential health benefits in Section 1302 is, Dr. Gruber said, “a fundamental change in the nature of insurance coverage in America. Never before have we mandated such a comprehensive set of insurance

benefits.” Although some categories of care are mandated, many benefits (e.g., infertility treatment, chiropractic care, subspecialty care) are not specified. Dr. Gruber’s experiences, he said, imply that the committee can expect to “hear from advocates, all with compelling arguments about important things to include.” The committee and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will need to make difficult decisions about how or whether to “go beyond the list” of categories included in the ACA.

Dr. Gruber reminded the committee that the ACA already eliminates annual and lifetime limits and requires maternity, mental health, habilitation, and pediatric vision and dental coverage. Such benefits, he noted, are not part of typical employer plans. The issue, he asked the committee, “is how much further do you want to go?”

Limitations on Coverage

Although the ACA prohibits annual and lifetime limits on coverage, it does not “rule out more specific limits,” such as limits on the number of mental health or physical therapy visits, or step therapies (e.g., requiring certain prescription drug regimens such as starting treatment with a generic drug). Consequently, Dr. Gruber said, HHS will have to address “the extent to which it wants to allow these sorts of limits on coverage or the extent to which it wants to say, ‘if a benefit is covered, it must be covered in an unlimited fashion.’” Moreover, decisions about one set of benefits can have repercussions for others. For example, the cost of adding a certain prescription drug benefit may vary depending on the extent of allowable mental health coverage because increased mental health coverage is associated with increased use of prescription drugs to treat mental illness.

Patient Cost Sharing

Dr. Gruber pointed out that the ACA provides relatively little guidance on cost sharing other than limiting the deductibles for small businesses and instituting out-of-pocket (OOP) maximums that are a function of income. The committee could decide, he said, to “make decisions” or “remain silent” about issues of cost sharing. For example, the committee could decide to advise the Secretary to have a maximum deductible for individuals, co-insurance not more than a specific amount, or co-pays not more than a specific amount. The committee could also advise the Secretary on the nature of cost sharing. In particular, Dr. Gruber suggested the committee consider providing guidance on “what the out-of-pocket maximum applies to” because the ACA does not “go into enough detail” (i.e., does it apply to everything in the insurance package). He advised the committee to have a broad OOP maximum if the idea is to protect people.

Committee member Dr. Santa commented that the ACA’s variation in OOP maximums by income is “an unusual aspect of benefit design” that may “create selection issues since health status tends to vary with income.” Dr. Gruber noted, however, that it is unlikely that people will strategically work harder to change their OOP maximum, so selection is not a “significant issue.” The variable OOP maximums, he noted, are “really about protection” from high costs as a function of income. West Virginia’s state employee plan, for instance, has a similar feature in which OOP maximums vary by income (Public Employees Insurance Agency, 2011).

Actuarial Value

Dr. Gruber briefly explained the concept of actuarial value to the committee and audience. Four levels of coverage are stipulated in ACA—bronze, silver, gold, and platinum—and each has differing actuarial values that reflect how much of the cost is borne by the insurer and how much by the patient.1 The silver tier of plans specified in the ACA has an actuarial value of 0.7, he said. This means that on average, across all of the people within the silver tier plan offered by an insurer, the insurer must cover 70 percent of the cost. In other words, for a healthy person who utilizes few services, the insurance company would cover very little because the person has not yet met the required deductible. For a sick person who incurs high medical costs, the insurer may cover close to 100 percent because the patient has considerably exceeded the personal OOP maximum. The actuarial values, he said in

____________________

1 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 as amended. Public Law 111-148 § 1302(d)(1)(A)-(D), 111th Cong., 2d sess.

response to an inquiry from committee member Dr. Selby, are based on a “given standard population” that could in reality look like the employer-sponsored insurance population or the uninsured, depending on who enrolls. The law appears to give insurers a lot of latitude in the ways in which they could achieve the various actuarial levels.

Affordability of Coverage

There is a fundamental tension, Dr. Gruber stated, “between our desire to make insurance as generous as possible and a desire to make the [EHB] mandate both moral and feasible by making health insurance affordable.” The more benefits included in the benefits package, the more expensive the package becomes, which in turn makes health insurance less affordable, causing people to opt out of coverage. The ACA’s mandate to buy health insurance, Dr. Gruber said, comes with an obligation to make health insurance affordable. Gruber argued that the tradeoff between cost and coverage should be the committee’s principal consideration and that actuarial analysis would help in making these decisions.2

The Consequences of Raising Costs

A Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis suggests that the ACA will cost approximately $950 billion by 2019 if the EHB package is comparable to an average employer-sponsored insurance plan. Of course, he said, if the package “gets more generous,” costs will rise with a variety of possible impacts. For instance, the individual mandate clause stipulates that if individuals would have to pay more than 8 percent of their income for health insurance, they are not subject to the mandate.3 A more generous, and thus more expensive EHB package, would therefore lead to more individuals eligible for exclusion from the mandate.

Furthermore, the financial exposure of individuals receiving federal subsidies to purchase insurance will be capped at a percent of their income; in these cases, the government is the residual claimant in that the government bears the additional costs of making the benefit package more expensive. Conversely, for individuals ineligible for federal subsidies (i.e., for individuals above 400 percent of the federal poverty level [FPL]), the individual policyholder is the residual claimant. Dr. Gruber highlighted this distinction because it shows who will face “the extra cost” of making the EHB package more expensive.

To consider the cost impact of coverage decisions, Gruber developed a micro-simulation model that he described as “calibrated to match what CBO produced for the score of the ACA” (Long and Gruber, 2011). To give the committee a sense of the implications of its recommendations, he used an extreme example: if the committee recommended an EHB package that raised the cost of insurance by 10 percent above the CBO’s estimate, government costs would rise by 14.5 percent.4 Additionally, this 10 percent increase in costs would erode the effectiveness of the insurance mandate: uninsurance would increase by 4.5 percent (approximately 1.5 million fewer people would be insured than if the committee had recommended an EHB package that cost 10 percent less). The fundamental tradeoff, then, is that making the EHB package more comprehensive undercuts the gains that could have been made by the ACA.

Minimizing Disruption

In addition to considering the tradeoff between comprehensiveness and affordability, Dr. Gruber suggested the committee consider minimizing disruption. “You are not just setting up a benefits package for people who used to be uninsured,” he said. “You are also setting up a benefits package for people who have insurance and by and large like it.” He reminded the committee that during the health reform debate, some politicians promised that “if you like your plan, you’ll be able to keep it” (The White House, 2009). There is a wide variance, though, in existing plans. Some people have very limited coverage (i.e., mini-med plans that only cover $100 a day in

____________________

2 The IOM committee was not given resources for actuarial analyses.

3 § 1501(e)(1)(A).

4 This is more than 10 percent because of the government being the residual claimant.

the hospital), while others have more generous coverage. If the EHB package is more generous than a typical employer-sponsored plan, it is going to raise costs and cause people to have to “buy up” from what they are currently happy with. Therefore, the committee should be aware, he said, of the political considerations involved in its decisions, including whether this variation in plans should “be allowed to continue.”

Lessons from Developing “Minimum Creditable Coverage” Requirements in Massachusetts

Dr. Gruber explained the “minimum creditable coverage” mandated by the Massachusetts legislature. He defined minimum creditable coverage as “the minimum level of coverage that people could hold and still meet the individual mandate.” He provided four examples to illustrate some of the issues the Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority Board faced when developing the minimum creditable coverage requirements: removing lifetime limits, removing annual limits in the young adult plan, mandating prescription drug coverage, and providing maternity coverage for dependents.

Removing Lifetime Limits

Dr. Gruber explained his argument in favor of prohibiting lifetime limits. Economic principles, he said, made it clear that “real insurance does not have a lifetime limit,” and “it seemed to me to make no sense to say if someone is incredibly sick, we are now cutting you off because you have achieved the limit.” The Connector Board, though, received volumes of data from insurance companies and unions, among others, showing that limits keep costs down. Furthermore, state policy makers intended the law5 to be “about covering the uninsured not telling insurers they had to change.” After much debate, the Connector Board allowed lifetime limits to remain in place.

Removing Annual Limits in the Young Adult Plan

Massachusetts’ young adult plan is a low-cost insurance plan designed for the under-26-year-old population. The plan allowed annual limits, which the Connector Board initially believed was “a fundamental problem.” Actuarial analysis revealed, however, that removing the $50,000 annual limit would raise the cost of the insur-ance by 15 percent. When examining this issue, the Connector Board considered that one of the principal aims of Massachusetts’ health reform law was to “get young people signed up for health insurance,” and as a result, the under-26-year-old population has had the largest increase in the rate of coverage. Furthermore, at the time the Connector Board was evaluating the annual limits, not one young adult had hit the $50,000 limit. The Connec-tor Board has not, to this day, eliminated the limit but will again be considering the issue in light of the ACA’s mandate to remove annual limits.

Mandating Prescription Drug Coverage

As Massachusetts was the first state to mandate prescription drug coverage (Reisman, 2008), the Connector Board had to determine what limits should be placed on that coverage. Some plans suggested covering a certain number of drugs each month, while other plans suggested covering up to a certain dollar exposure each month. Using evidence from the Medicaid program, which had recently instituted prescription drug limits, the Connector Board determined that the limits could have considerable health and cost implications. The Connector Board decided to ban “flat limits” on prescription drug coverage, even though the board knew this ban would raise costs. The Board decided, however, to allow insurers to appeal a denial of their prescription drug practices on the grounds that the practices were an innovative way to control cost.

____________________

5 An Act Providing Access to Affordable, Quality, Accountable Health Care. Chapter 58 of the Acts of 2006 of the Massachusetts General Court (April 12, 2006).

Providing Maternity Coverage for Dependents

Dr. Gruber described the question of whether to cover maternity coverage for dependents as “the most daunting political issue the board faced.” The issue arose because insurers had to provide dependent coverage, and Massachusetts had mandated the coverage of maternity benefits. A number of organizations in the state (particularly Catholic hospitals) argued, however, that their health insurance plans should not cover maternity benefits for dependents. A very vigorous debate ensued, Dr. Gruber said, and the Connector Board decided that the minimum creditable coverage did need to include maternity coverage for dependents.

Lessons from Massachusetts

The “fundamental lesson to be learned” from these four examples, he said, is that the committee cannot anticipate all the issues that will arise in implementing the EHB package. Therefore, he said, HHS has to make a tradeoff between the rules of coverage imposed and the flexibility created through an appeals process for insurers and employers on what should be in a benefit package. The tighter the rules are, he said, “the more people are going to want to appeal them.” While Massachusetts instituted a “very flexible appeals process for insurers and employers,” Dr. Gruber cautioned that the process is time consuming and leads to “enormous uncertainty” for employers. Flexibility at the outset, he said, will provide some room for restrictions to get tighter over time.

Dr. Gruber concluded by reiterating that the committee should “start modestly.” Additional requirements beyond what are already included in the ACA will add costs to both the public and private sectors and undercut support for the ACA. Moreover, the committee should remember, he said, “that insurance design is dynamic” and that “it is important to set up a process that evolves over time and is flexible to innovation.” The Connector Board, he said, is “a learning organization” in that it has a process to revisit issues rather than “imposing” too many restrictions at the outset.

When committee member Dr. McGlynn asked Dr. Gruber what, in retrospect, the Connector Board should or should not have done, he advised the committee that the Connector Board did not incorporate cost estimates enough. Specifically, he said, the board did not “define the target and then have actuaries inform the committee about the tradeoffs inherent” in decisions. Now, he said, the Connector Board discusses options at its meetings, sends those options to actuaries to score, and reconvenes to vote on those options based on the actuarial score. This way, even when a Board member does not agree with the outcome, “it is a fine process.”

PRESENTATION BY DR. JON KINGSDALE, WAKELY CONSULTING

Before his current role as managing director at Wakely Consulting, Dr. Kingsdale directed the Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority, an institution delegated by the Massachusetts legislature to determine certain policy issues, including the mandated “minimum creditable coverage.”6 Framing his advice as being “experientially based,” Dr. Kingsdale began by identifying three issues for the committee’s consideration: (1) defining EHB will be one of the most challenging parts of implementing the ACA, (2) the committee and HHS will have to make its decisions based on a short, highly prioritized list of principles, and (3) the committee and HHS will need to make decisions based on partial information.

Challenges of Implementing the ACA

Beyond the “obvious realities of how controversial and passionate people are about defining benefits,” and “the enormous dollar implications both for consumers and payers,” Dr. Kingsdale identified a further challenge in defining the EHB: the ACA does not have broad stakeholder support, and the committee “is undertaking its task in a highly divided nation.” In Massachusetts, state reform efforts enjoyed “broad political support.” Whatever is put into the EHB package, he said, “can be portrayed by opponents of the ACA as unfairly burdening employers

____________________

6 Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority 956 CMR 5.00: Minimum Creditable Coverage. Full text available at http://www.lawlib.state.ma.us/source/mass/cmr/cmrtext/956CMR5.pdf.

or individuals who want a lesser package.” On the other hand, proposing a “lesser benefit package” will disappoint some supporters of the ACA and individuals who think that the ACA did not go far enough. Dr. Kingsdale suggested that “overreaching could doom implementation,” so the committee should err on the side of being “conservative” about adding to the EHB package.

Suggested Principles for Consideration

Dr. Kingsdale began by explaining what he called potentially “obvious” things about the realities of purchasing health insurance. There is a tendency, he said, to think about benefits in the context of “something someone else will pay for.” He noted, however, that “there are real people who cannot afford what we consider to be an ideal benefit package, and they actually have to pay for it in premiums.”

Dr. Kingsdale said his experience implementing components of Massachusetts’ health reform law,7 including defining minimum creditable coverage, suggests that there is broader popular and political support of the goal of reform laws, such as the ACA, being “about giving more people decent coverage as opposed to being about raising the standard of coverage.” He advised the committee, therefore, that when it has to “make decisions about close calls regarding benefits,” it is important to return to this purpose as a guiding principle. Second, he said, the ACA “will live or die on affordability.” Most benefits, though, are costly, regardless of notions frequently promulgated that additional benefits save money. Lastly, he said, there is a “fair degree of consensus around the minimum benefits.” There are very few benefits beyond those typically covered by commercial insurance that significantly improve population health or reduce costs.

Decision Making Based on Partial Information

Dr. Kingsdale concluded by sharing what he believed the committee could learn from the Massachusetts experience. Massachusetts did not mandate its minimum creditable coverage stipulations until two years after the law passed. This timeframe eased acceptance and facilitated an orderly transition to implementation. Furthermore, he added, during those two years, his organization learned from employers and insurers about “exceptional cases” that would not fit into a set of minimum creditable coverage requirements. Dr. Kingsdale suggested that the committee similarly phase-in EHB requirements or, at least, consider case-by-case exceptions after the EHB requirements have been instituted. These case-by-case considerations proved to be “very educational” in Massachusetts; they allowed the definition of minimum creditable coverage to evolve. The Connector Board annually revisits the topics raised.

Dr. Santa noted that once covered benefits are determined, there are other important variables to consider, including utilization, price, and quality. Once benefits are determined, he asked, “how much of the problem is solved?” In answering, Dr. Kingsdale recalled the issue of dependent maternity coverage raised by Dr. Gruber. The “tough questions” in this case, he noted, “are not cost implications” or related to scientific evidence. When Dr. Santa asked Dr. Kingsdale if his agency considered the costs of coverage against the rates of caesarean sections, adverse events, and the price of delivery at a hospital, Dr. Kingsdale replied that the “larger issue” was the perceived “imposition of management decisions” on employers “who felt they offer perfectly good health benefit packages.”

PRESENTATION BY DR. BETH SAMMIS, MARYLAND INSURANCE ADMINISTRATION (MIA)

Dr. Sammis, Acting Insurance Commissioner, began by stating that in a previous role, she was intimately involved in the development of a standard benefit plan in Maryland. This plan, which is called the Comprehensive Standard Health Benefit Plan (CSHBP), was developed by the Maryland Health Care Commission (MHCC) after the Maryland Health Insurance Reform Act of 1993 mandated that all carriers participating in the small employer market must sell the CSHBP to any small employer who applied for it. The objective of the law, Dr. Sammis said, was to allow small employers to be better able to compete with large employers in the state, including the federal

____________________

7 An Act Providing Access to Affordable, Quality, Accountable Health Care. Chapter 58 of the Acts of 2006 of the Massachusetts General Court (April 12, 2006).

government, by providing small employers with access to affordable, comprehensive health plans for employees. The standard also facilitated comparison of benefit plans. The CSHBP had to (1) be actuarially equivalent to the minimum benefits required to be offered by federally qualified HMOs and (2) have an average premium that did not exceed 12 percent of Maryland’s average annual wage. These standards guided the development of the CSHBP by establishing a “floor” and “ceiling” for benefits. Dr. Sammis noted that the legislature allowed the Health Care Access and Cost Commission (now the MHCC) to exclude state-mandated benefits from the CSHBP and required the Commission to consider the benefit plans provided by large employers in Maryland.

Process of Determining Benefits

The task force created by the Commission to design the CSHBP began by examining 70 policies submitted by carriers and employers in Maryland and choosing eight representative policies. Using these representative policies, the task force developed a list of “controversial benefits” based on expert opinion and public comment. Next, the task force identified a set of benefit design options, priced these using actuarial analyses, and then again solicited public comment. Throughout the entire process, the task force grappled with the question of “what are essential benefits,” as well as what benefits were important to the public and what the role of cost in determining the benefit plan would be. Ultimately, the task force recommended specific covered services, limitations, and exclusions, and the cost sharing for indemnity, PPO, health maintenance organization (HMO), or point-of-service (POS) plans.

Medical Necessity Determination

The CSHBP, Dr. Sammis explained, excludes services and supplies that are not medically necessary. While there is no single medical necessity definition in state law, carriers must abide by statutory medical necessity determination standards. These standards are that medical necessity protocols must be objective, clinically valid, compatible with principles of health care, flexible, and abide by standards promulgated by accrediting bodies (i.e., the National Committee for Quality Assurance [NCQA] and Utilization Review Accreditation Commission [URAC]). Every carrier in Maryland, including those outside the small group market, is required to file its utilization review plan and criteria with the MIA.

When an individual’s request for coverage is denied and then appealed to the MIA, medical experts address whether the criteria used by the carrier to reach its determination meets the statutory standards and were appropriately applied in the specific case. If the medical necessity criteria have not been appropriately followed, the Insurance Commissioner has the authority to order the carrier to pay for the service and to modify the carrier’s medical necessity criteria to incorporate the recommendations of the medical experts.

One of the major concerns of carriers arises when a carrier is ordered to change its criteria as a result of an appeal. Carriers perceive that they are put at a competitive disadvantage because other carriers have not been ordered to provide the same coverage despite that they may have a similar noncoverage policy as the carrier that was ordered to provide coverage. For example, Dr. Sammis’ department had to determine if because the CSHBP does not expressly exclude coverage for human growth hormone (HGH) for idiopathic short stature (a common exclusion in other market segments), it should be covered when medically appropriate in the small group market. The MIA received a complaint about a denial for HGH for idiopathic short stature for a dependent under a small group policy. The independent review organization determined that HGH was medically necessary in this case and that, more generally, it should be covered under specific circumstances.

As a result, Dr. Sammis has committed to establishing a more transparent process for when a medical expert notifies her that a carrier’s criteria are not in compliance with the statutory requirements. That way, when she orders a carrier to modify its criteria, she can notify all of the other health plans in the marketplace. In addition, she is developing a process by which the MIA performs a six-month or one-year review to see whether or not other carriers have, in fact, adjusted their criteria. When prompted by Dr. Selby, Dr. Sammis confirmed that Maryland does not provide guidance on the application of principles of medical necessity to the evaluation of cases. The only specific medical necessity guidance that Maryland has provided relates to when gastric bypass surgery could be considered medically necessary.

When the CSHBP was initially implemented, Dr. Sammis said, the small group market reforms were “quite successful in cost containment” partially because of the “death of indemnity plans.” She described Maryland’s small group market reform as having “moved the entire market out of indemnity plans into PPO and HMO plans.” Although these initial successes in cost containment have not been maintained, Dr. Sammis does not believe this to be unique to the standard benefit plan in Maryland. After all, she said, the CSHBP is the floor, and only about 2 percent of the state’s small employers buy this level of coverage, opting instead to buy additional benefits (MHCC, 2007; Wicks, 2002).8

PRESENTATION BY DR. REX COWDRY, MHCC

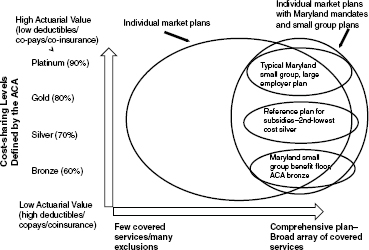

Dr. Cowdry, Executive Director, expanded on Dr. Sammis’ review of CSHBP’s origins and described how the CSHBP relates to the benefit tiers established by the ACA (see Figure 4-1). He considered planning along two separate dimensions: the breadth of services and cost sharing. Keeping these dimensions separate, he said, is important as the processes for determining cost sharing might differ quite drastically from those for determining the breadth of services offered. In Maryland, for example, when the premium cap for the comprehensive standard plan was reduced from 12 percent to 10 percent of the average wage in the state, the MHCC had to consider whether it should limit benefits or adjust cost-sharing arrangements. The MHCC, Dr. Cowdry said, avoided the difficult decisions necessary to reduce covered services. Although cost sharing was increased to meet the premium cap, the increase had little effect on costs or affordability because “people still purchased riders to create more generous plans with less cost sharing.” With the exception of pharmacy benefits, modifying cost sharing rather than reducing benefits has continued to be standard practice. When the MHCC decided to “modernize” CSHBP’s rigid three-tiered pharmacy benefit plan to allow for value-based incentives, it created a less expensive core pharmacy benefit that allowed employers to purchase a variety of pharmacy riders at modified community rates.

Lessons Learned

Once benefits are issued, Dr. Cowdry noted, “it is very hard to stop covering services or refuse to pay for them.” Additionally, “too much design specificity or standardization prevents” the kind of innovation needed to control health care costs. Greater specificity can interfere with the ability to craft a “sensible” package. The ACA includes cost sharing limits, he said, including a “hard floor” at the bronze level, a subsidy floor at the silver level, and OOP maximums. With these cost-sharing specifications in place,” Dr. Cowdry asked, “the question now becomes: should the EHB package only address the breadth of coverage service decisions?” One approach would leave cost-sharing decisions to the states. The EHB package would be based on the broad categories in the ACA, and refined and defined using the contractual provisions of the “typical” employer plan with detailed coverage policies developed by carriers based on evidence of effectiveness and specific cases addressed through medical necessity determinations. This option, he said, “moves with the times” as new evidence “strengthens the way we determine medical necessity” and provides greater uniformity to that process.

Contract Limits

Dr. Cowdry referenced Ms. Helen Darling’s testimony (see Chapter 3) to support his claim that some benefits—especially those without clear indications or guidelines—may be better managed with an annual limit on cost or frequency, such as how physical therapy visits have been limited contractually.

Dr. Cowdry suggested that the ACA and other statutes may make it difficult to implement appropriate limits on services based on scientific evidence. For example, the ACA prohibits lifetime limits and phases out annual limits. Additionally, for employers with more than 50 employees, the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health

____________________

8 The Maryland Insurance Administration also surveyed the largest carriers in 2008 regarding the top five benefit plans sold to small employers. These results were not published.

FIGURE 4-1 The benefit categories in the ACA could vary in breadth and depth of coverage.

SOURCE: Cowdry, 2011.

Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 20089 prohibits service limits and cost sharing for mental health and substance abuse treatments that are more restrictive than the service limits and cost sharing for most medical-surgical benefits. Dr. Cowdry argued that together, these statutory constraints may make it difficult to craft an appropriate, effective, and cost-effective benefit. For example, for autism he reported that their reviews of the limited evidence available regarding the treatment of autism suggested that intensive interventions from ages two to six offer substantial promise, but Maryland’s Attorney General has suggested that a benefit focused solely on those ages and including an annual limit would violate the law. Dr. Cowdry expressed uncertainty about how, given statutory constraints, the use of specific services for specific conditions can be limited through the benefit design process.

Mandate Review Process

Maryland’s General Assembly enacted an annual mandate review process that aims to deter the enactment of what Dr. Cowdry called “bad mandates” based on impassioned advocacy rather than good evidence. Although the process is not perfect, he said, it considers evidence of the clinical, social, and financial impact of the mandate. He also described Maryland’s quadrennial mandate review process that estimates the costs of all of Maryland’s mandates—both the full cost of the covered service and the marginal cost of the mandate (i.e., the incremental cost of benefits beyond those included in a typical, large employer’s self-insured plan). Mercer’s report to the MHCC indicates that the full cost of Maryland’s mandated benefits is approximately 18.6 percent of individual premiums (see Table 4-1) and 15.4 percent of group premiums. However, the marginal cost of these state mandates is only approximately 2.2 percent of group premiums because most of the mandated benefits are already voluntarily available in comparative self-funded plans which are exempt from mandates. If benefits not covered in the small group market (e.g., in vitro fertilization) are not considered, the marginal cost is closer to 1.5 percent (MHCC, 2008).

____________________

9 Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. Public Law 110-343, 110th Cong., 2d sess. (October 3, 2008).

|

|

||

| Mandate | Full cost as percent of premium–individual market (%) | Marginal cost as percent of premium (beyond typical self-insured large employer plan) (%) |

|

|

||

| Mental illness, substance abuse | 5.9 | 0.5 |

| In vitro fertilization | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Childbirth | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| Length of stay for mothers of newborn | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| Child wellness | 1.5 | 0.0 |

| Diabetes equipment, supplies, self-management training | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| Contraceptives | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Treatment of morbid obesity | 1.0 | 0.2 |

| Smoking cessation | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Others (each < 0.05%) | 3.4 | 0.5 |

| TOTAL | 18.6 | 2.2 |

|

|

||

| SOURCES: Cowdry, 2011; MHCC, 2008. | ||

Comprehensive coverage may “be the right place to be” if such coverage can be merged with value-based incentives to patients and providers and a rigorous process to exclude non-medically necessary interventions. State exchanges, he suggested, “can be laboratories for exploring different limits and the kind of cost-sharing designs that make sense.”

PRESENTATION BY REPRESENTATIVE JAMES DUNNIGAN, STATE OF UTAH HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

Representative Dunnigan, an insurance broker with Dunnigan Insurance, has served in the Utah House of Representatives since 2003, and as Chairman of the Utah Health Exchange Oversight and Implementation Working Group has been involved in the debate and the development of Utah’s health reform law, passed in 2008.10 He began by noting that he was speaking on behalf of state legislatures across the nation in urging the committee to recognize state differences and the impact of EHB decisions on state budgets.

Recognizing State Differences

Representative Dunnigan suggested that the committee “preserve state flexibility,” as the scope of benefits offered in the EHB package will be a “significant factor” in the cost of the qualified health plans (QHPs) offered in insurance exchanges. The ACA, he noted, stated the scope of benefits should be equal to the scope of benefits provided under a typical employer plan, and told the committee that this is “problematic” for states because what is typical in one state may not be typical in another due to state mandates, for example. “To avoid imposing the political choices of each state on 49 others,” he said, “the Secretary should allow what is typical to be determined on a state-by-state basis.” In the case of a multi-state exchange, what is typical should be determined on a multi-state basis. Furthermore, he recommended that the Secretary allow states to “spell out” the definitional details of the categories listed in Section 1302. In lieu of state specification, he proposed the creation of a three-tiered approach for the EHB package:

- Tier 1: limited to those benefits provided under a typical employer plan offered within the geographic boundaries of an exchange.

____________________

10 Health System Reform, H.B. 133, State of Utah General Session (March 2008).

- Tier 2: benefits that extend the coverage of a typical employer plan. These benefits would be value-driven and have a strong evidence base. States would elect, on a state-by-state basis, whether to include tier 2 benefits in their EHB package.

- Tier 3: any other benefits that a state may wish to include.

Under Representative Dunnigan’s plan, exchange subsidies for tier 1 and tier 2 benefits would be fully funded by the federal government and subsidies for tier 3 benefits would be fully funded by the respective states.

Recognizing the Impact on State Budgets

Representative Dunnigan advised HHS to reach out to state insurance commissioners and health department directors to gather evidence on the cost implications for including and excluding certain benefits. Additionally, he asked for consideration of the implications of the EHB package on state Medicaid programs. Each state’s Medicaid program uniquely reflects the fiscal capacity and political preferences of the sponsoring state; the Medicaid expansion “will have a direct impact” on state budgets. This impact is especially true once the responsibility for funding the newly eligible persons shifts from the federal government to the states in 2017. At that time, Representative Dunnigan said, states will have to either raise additional revenue or, more likely, divert funding that “would otherwise go to other important services like transportation, corrections, and education.” Medicaid has been “competing with and sometimes crowding out other essential government services since its inception,” Representative Dunnigan said. The EHB will not apply to traditional Medicaid, but does apply to Medicaid benchmark and benchmark-equivalent programs.

The EHB package could affect any program for which there is mandated coverage, including Utah’s purchase of insurance for state employees and the employees of state-funded entities such as school districts and institutes of higher education. As Utah assumes 95 percent of premium costs for the state employees’ health insurance plan, EHB determinations will directly impact state costs. The degree to which legislatures will have to either raise new revenue or reduce funding for other essential services or decrease employee compensation will “depend in large measure” on the initial definition of the EHB package, as well as on subsequent revisions of this package.

The implementation of the ACA, Representative Dunnigan said, may result in employers who currently offer coverage to drop coverage. Those previously covered employees, then, may be Medicaid eligible, and states will become liable for people previously covered in the private market. Although the costs of this phenomenon are unknown, Representative Dunnigan expressed that this situation will certainly arise in some states “if the Secretary establishes a national one-size-fits-all essential benefits package.”

Utah’s Insurance Exchange

When committee member Dr. Nelson asked Representative Dunnigan for details on how the Utah exchange is working, Representative Dunnigan noted that Utah began by operating a pilot program of the exchange for small employers; the exchange opened to the broader market of small and large employers in January 2011.11 By February 2011, 62 employer groups were participating (covering about 1,300 lives). Subsequently, additional employer groups joined. Utah opted to phase-in the program, he said, because it allows the state to address issues as they arise.

This discussion of the exchange prompted Dr. Nelson to ask for further details about how the state determined the basic benefit package. Representative Dunnigan said the basic benefit package has been in place for “a number of years.” Utah NetCare, which is Utah’s “version of an EHB package,” was designed to be a third less expensive than the average employer-based premium in the market. While the basic benefit package is currently available and being purchased, “most people purchase benefit packages in excess of the basic requirements.”12

____________________

11 As of March 30, 2011, the Utah exchange is no longer permitting large employer participation (State of Utah, 2011).

12 According to Utah’s largest commercial insurer with about 50 percent of the market, the enrollment or uptake in the minimum NetCare among their members represents about 0.005 percent of the overall market. Personal communication with James Dunnigan, May 4, 2011.

PRESENTATION BY MR. MATTHEW SALO, THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION (NGA)

Mr. Salo, the Director of the Health and Human Services Committee of the NGA concluded the panel by discussing implementation issues related to insurance exchanges. Even before the passage of the ACA, he said, the NGA had convened groups of key state officials (e.g., governors’ offices, health officials, Medicaid directors, and insurance commissioners). These conversations, among others, allowed Mr. Salo to confirm statements made by the previous panelists: notwithstanding the passage of the ACA, health insurance “does remain and will remain” largely a state issue. This holds true, he said, “whether you are talking about regulation, or licensure, or coverage mandates, or the state’s role as a purchaser of health insurance.” By 2014, he claimed, states will be the largest purchaser of health insurance in this country.

State Flexibility

Mr. Salo echoed Representative Dunnigan in saying that because political and cultural factors drive health insurance regulation, benefit mandate decisions, and benefit design, state-by-state decision making is necessary. Mr. Salo argued that “this flexibility will avoid dealing with a national standard that many states cannot meet either because it is too high, or because it is too low.” He emphasized that governors need a “highly flexible framework” for determining state-specific benefit packages that “drive innovation” through value-based insurance design (VBID). Conversely, granular federal mandates about types of services and duration of services, he said, will inhibit innovation. Dr. Kingsdale interjected, noting that he disagreed that states should have flexibility in determining the EHB package. The ACA specifies, he said, a national EHB package. Mr. Salo concluded by advising the committee to consider fiscal and political sustainability by ensuring its recommended EHB package is realistic from fiscal and political perspectives.

Question & Answer Session

Committee member Dr. McGlynn asked the panelists to comment on the role of the government in developing a process for “gathering the evidence needed for decision making” given that states are “cash strapped,” states may be unable to gather this evidence on their own, and that a federal process may prevent state-by-state inconsistencies in the evidence used. Dr. Cowdry responded that research undertaken by large carriers or “independent institutions that have been set up to do exactly this kind of guideline development and guidance” could prospectively minimize discrepancies in evidence as opposed to addressing discrepancies only through an appeals process. He cautioned, though, that this process would need to be insulated from politics and that Medicare should not “dominate” the process. There is a need for private sector entities, Dr. Cowdry said, “to come to a greater agreement about what is medically indicated.”

Representative Dunnigan supported Dr. Cowdry’s argument, noting that these determinations need to come from the scientific community, not from policy makers. “If there could be a national standard of evidence-based medicine and favorable outcomes that the states could evaluate and adopt,” he said, “it needs to be divorced from policy makers.” Dr. Kingsdale added that while Massachusetts analyzes the cost impacts at the state level “as new benefits or proposals crop up,” a national database and national analysis would “make a lot of sense.”

Committee member Mr. Koller followed up on these responses by asking the panelists for ways in which the EHB process could “assure relative integrity, preserve flexibility but secure some degree of consistency, and reduce the state-to-state variation seen in practice.” Dr. Sammis responded that Maryland’s MHCC can estimate the cost of its standard benefit plan because the plan has “specificity between the benefits, the limitations, the exclusions, and the cost sharing,” rather than having just a list of benefits. It is not possible, she said, “to price out benefits” without considering the cost-sharing requirements. The specification of the EHB would “provide some guidance to the carriers as to what types of criteria they need to be mindful of when they develop policies and procedures for medical management.” She cautioned the committee that being too “prescriptive about cost sharing” would impede state decisions about what level of cost each state is “willing to impose upon its own citizens.”

Cowdry, R. 2011. Comprehensive and standard. The Maryland CSHBP experience. PowerPoint presentation to the IOM Committee on the Determination of Essential Health Benefits by Rex Cowdry, Executive Director, Maryland Health Care Commission, Washington, DC, January 13.

Long, P., and J. Gruber. 2011. Projecting the impact of the Affordable Care Act on California. Health Affairs 30(1):63-70.

MHCC (Maryland Health Care Commission). 2007. Options available to reform the Comprehensive Standard Health Benefit Plan (CSHBP) as required under HB 579 (2007). Baltimore, MD: Maryland Health Care Commission.

——. 2008. Study of mandated health insurance services: A comparative evaluation. Baltimore MD: Maryland Health Care Commission.

Public Employees Insurance Agency. 2011. Shopper’s guide: Plan year 2012 benefits. July 1, 2011-June 30, 2012. Charleston, WV: West Virginia Public Employees Insurance Agency.

Reisman, M. 2008. Universal health care in America: Can the Massachusetts model work nationwide? Pharmacy and Therapeutics 33(9):544-545.

State of Utah. 2011. Utah Health Exchange: Large employers. http://exchange.utah.gov/find-insurance/large-employers (accessed August 15, 2011).

The White House. 2009. Remarks by the President on health care and the Senate vote on F-22 funding. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/Remarks-by-the-President-on-Health-Care-and-the-Senate-Vote-on-F-22-Funding (accessed May 4, 2011).

Wicks, E. K. 2002. Assessment of the performance of small-group health insurance market reforms in Maryland. Washington, DC: Health Management Associates.