Following Ratzan’s presentation, three speakers were invited to provide comments on the commissioned paper which had been made available to them prior to this workshop.

Robert Gould, Ph.D.

President

Partnership for Prevention

Gould said he enjoyed the emphasis in Ratzan’s presentation on the cost-effectiveness of prevention. One way to protect the prevention provisions of various legislative actions is to understand that prevention is a way to save costs in the health care system. Gould said he spends his time in primary prevention, and, from a social marketer’s perspective, defines health literacy as the effective engagement of the public in getting and staying healthy. He has worked on social marketing projects such as developing campaigns for hypertension, cholesterol, and the Food Guide Pyramid. The prevailing attitude of those preparing the campaigns was that if the public does not understand the message, then it’s not the public’s problem, but rather it is up to the marketers to clarify.

In a campaign called the Healthy Older People Campaign, Gould said he and his team recognized the importance of crafting a print media campaign that the target audience could understand. Materials were printed in yellow and black with sharp contrasts in order to accommodate elderly populations that cannot see well. The campaign also made sure that the

reading level of all materials was appropriate for the audience. According to Gould, social marketers already consider health literacy in their efforts, though they define it as effective public engagement.

Gould’s concerns with the paper’s focus were in regard to behavior change and using social marketing to improve equity and promote health. Behavior, he said, is not determined solely by knowledge. Therefore, it is important to focus on what other methods, in addition to fostering knowledge, can be used to create the desired behavior. Many people understand the messages and have the knowledge, but do not act on it due to other barriers or beliefs. For example, a small subsample of teens known as high sensation seekers understand the risks of smoking, and still engage in the behavior despite this knowledge—some even enjoy taking the risk. The Truth campaign (http://www.thetruth.com) targeted this population by presenting tobacco corporations as manipulative and terrible, and leaving the decision of smoking up to the consumer.

Gould expressed his support for the policy recommendations made in the paper. Health literacy from Gould’s perspective is an umbrella term that means effectively engaging the public. Such engagement is required for prevention efforts to be successful, he said, and primary and clinical prevention are key investments in the public’s health.

Charles J. Homer, M.D.

President and Chief Executive Officer

National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality

Homer focused his comments on quality, which he defined generally as delivering the right care to the right person at the right time. In Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001), quality health care is defined as having six characteristics: safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered. Patient-centered or family-centered care means that the care meets the needs of patients and families and is communicated in a way that can be understood. This is particularly important in the areas of chronic care and of prevention because in order to make care effective, one must influence behaviors, and the only way to influence behaviors, Homer said, is through patient- and family-centered care.

Quality is related to the construct of health literacy because meeting the needs of patients and families requires clear communication. Clinicians focus on reliable and effective delivery of care, and they are increasingly turning to public health methods of quality measurement and improvement to enhance performance.

The National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality places a major focus on childhood obesity and on applying the principles of quality improvement in both clinical and community settings, Homer said.

This focus has lead to an examination of how one communicates with patients about health behaviors for children, behaviors such as healthy eating habits and active lifestyle. Unfortunately, the methods of communication taught in medical school are wrong for effective communication. Doctors are trained to act as the experts and tell patients what to do, whether they are interested or not. Similarly, clinicians have become acutely aware of the limits of clinical prevention in affecting a problem as broad as obesity—what is needed is a focus on change in the context of the community.

Reflecting on the paper, Homer commented that it points out that there are multiple levels of prevention—primary, secondary, and tertiary—some of which takes place in the community context and some in a clinical context. He highlighted the concept of active agency—that is that an individual takes an active step toward a health outcome such as choosing either to exercise or not to exercise, or to wear a seatbelt or not to wear a seatbelt. These actions can take place in either a conducive environment or a hostile environment. For example, the message can be that one should eat a healthy diet, but if the community lacks healthful food options (a hostile environment), it is unlikely that the individual will eat a healthful diet. Prevention efforts need to take into account the context of the individual’s environment.

There are also passive strategies to influence prevention, which the paper mentions only in passing. With passive strategies the individual is not involved in making a decision or taking an action toward the preventive measure. For example, policymakers have decided to put fluoride in the water; the individual drinking the water does not decide to take that step. The role of the individual is in influencing that community policy to either support or not support the fluoridation of water. The importance of health literacy in this context is to inform members of the public so that they can influence policy decisions.

How, Homer asked, would enhanced health literacy improve prevention-oriented behaviors in both the clinical context and the community context? In the clinical context, health literacy can help primary prevention efforts by helping people understand risks and benefits, understand the actions they have to take, and potentially, enhance motivation. In secondary and tertiary prevention, health literacy efforts can be aimed at helping people prevent complications or worsening conditions. In secondary and tertiary prevention the kinds of actions required of people are likely to be more complex as are the challenges of communication. Therefore, the need for close attention to health literacy is greater and may require the kind of interactive decision tools in which the information presented is customized to individual risk.

The paper also mentions the need to decrease the complexity of the

health care system, Homer said. While this is certainly true, complexity is not the main barrier to primary prevention. In obesity, what is particularly helpful to is to have health navigators understand the complex set of community resources and help individuals access them, rather than helping individuals obtain access to primary care services.

The issue of provider training is also addressed in the commissioned paper and is absolutely essential, Homer said. Medical providers need to be trained in communication in a more rigorous manner than just a course in first-year medical or nursing school. Other health professions should also be trained in health literacy and such education should be required for certification or licensure, Homer stated. Furthermore, health literacy should be incorporated into the public education system to help develop informed health consumers, Homer said.

Additional strategies the paper could have commented on include training consumers and youth in these types of issues, Homer said. Another strategy would be to develop prevention specialists in the community who could work with multiple providers. The importance of longitudinal relationships cannot be overemphasized, Homer said. If one is trying to change behavior, having a trusting relationship built over time is a critical mediator. Another important area is payment reform. Our current fee-for-service health care delivery system is completely at odds with an emphasis on prevention.

Community change is critical in the preventive context, Homer said. One focus of health literacy should be how to enhance prevention-oriented behaviors in the community. This requires communicating to the public about ways to be more effective in influencing public policy, both at the national level and at the community level, where prevention issues include which programs school boards will fund and whether streets will have bike lanes and sidewalks. Successful prevention efforts at the community level are a matter both of understanding and prioritizing risk and of balancing health with other priorities. Most people are not primarily motivated by health; they are primarily motivated by wanting to do the things that are important to them.

Homer commented on the specific strategies in the paper. He would have liked greater elaboration on how to equip families with self-care strategies. In terms of workplace wellness, while programs that encourage healthy behavior in the workplace are important, there are some ethical issues that cause concern, he said. Would employers make decisions about hiring based on health behavior?

Homer also expressed skepticism about the health scorecard concept because it is based on individual responsibility in the absence of community interventions, which can create blame for the individual. It is not clear that scorecards would serve as appropriate individual motivation,

and there is potential harm if they were to be used inappropriately in guiding employment practices.

Overall, Homer concluded, it is important to clarify the scope and focus of health literacy interventions, including general capacity, competency with specific preventive actions, and motivation and prioritization. It is also important to decide if the individual interventions will focus primarily on clinical prevention or community prevention even though there is and should be interface between the two. It is also important, Homer said, to address developmental issues of different life stages: parental/ early childhood stage, adult, and elderly.

Mariela Yohe, M.P.H.

Program Director

Directors of Health Promotion and Education

Maxene Spolidor was unable to attend the meeting due to illness. Mariela Yohe delivered her comments.

The Directors of Health Promotion and Education is an organization that represents the directors of health promotion and education at specific state and territorial health departments. The directors administer a wide range of programs, dealing with issues from chronic disease and tobacco prevention to injury prevention, and members have the skills to implement, evaluate and create public health and education programs.

Communication activities have been major components of state health department programs funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), many of which specifically address issues of literacy and cultural linguistic appropriateness for interventions, outreach, education and social marketing strategies. For example, in Massachusetts, a recently funded program to improve breast and cervical cancer service delivery through the WISEWOMAN program included a health literacy training component for community health workers, who act as patient navigators or care coordinators for the patients receiving care through federally funded community health centers and safety-net sites. In another effort, staff involved in the delivery of evidence-based health promotion programs for people over 50 were trained in health literacy, ensuring that patients receive care that is linguistically and culturally appropriate with an added emphasis on literacy considerations. Health promotion activities undertaken by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health do not place the burden of understanding complex information on the consumer. Rather, the department accepts responsibility for delivering its services and messaging to all audiences, with an emphasis on literacy and cultural/linguistic appropriateness.

Comments on the Ratzan paper included questions about who, spe-

cifically, would be responsible for funding, organizing, delivering, and evaluating consumer education aimed at helping people understand complex health conditions. How would continuity of education be ensured if less-advantaged populations may move frequently and change providers, Yohe asked? The advancement of health literacy cannot rely on the model of the medical home, she said.

Yohe expressed hesitation about the scorecard as a motivator, suggesting that members of a disadvantaged population may have greater barriers to overcome than scoring well on scorecard indicators. She said that perceived barriers to health care need to be lowered but the scorecard may feel like a new, judgmental obstacle for some people. She agreed with Homer that it is important to make sure that health education, which could include health literacy, is available in schools, although it is already difficult to keep current programs funded. Furthermore, telling individual school systems what and how to teach is a daunting task.

Yohe said that she would rather see resources concentrated on keeping health education as a core component of public education for all U.S. children than set up scorecards and other devices that may throw the onus of understanding complex information on the patient rather than on the health provider.

The paper’s recommendation “to develop, test, and implement health communication approaches to advance wellness and prevention so that skills and abilities of the population can be aligned with the demands and complexity of the tasks required for health” places an additional burden on programs that are currently underfunded and understaffed, Yohe said. Public health agencies are generally not concerned with educating the public on health literacy, but instead such agencies are providing interventions in the most appropriate health-literate vehicle that they can design and implement. Ratzan mentioned flu as an example in his paper. If one looks at the CDC website on flu (http://www.pandemicflu.gov) one will find programs that address consumers’ needs and abilities to understand complex information.

The second recommendation in the paper calls for the Office of the Surgeon General or the Domestic Policy Council to convene and guide agencies to fund and create a Health Literacy P-scorecard in each state. But this requires a set of universally accepted indicators. Which government agency would be charged with developing those indicators? Who would collect, analyze, and disseminate the information?

Concluding her presentation, Yohe said she agreed with several of the recommendations including

- the need for health care systems to develop programs that simplify the demands and complexity of the system (recommendation 5);

- that there should be a health literacy competency base for different levels of education (recommendation 7); and

- that accrediting boards should incorporate primary and secondary prevention health literacy into their requirements.

But, she said, it is not clear how a scorecard would facilitate these recommendations. Also, it is not clear, she said, how quality standards that reduce the demands and complexities of the health system (Recommendation 6) improve health literacy.

DISCUSSION

George Isham, chair of the Roundtable, observed that each of the speakers appeared to struggle a bit with the concept of health literacy, with the definition of health literacy often varying across speakers. This emphasizes the importance of properly communicating this concept to key groups and also emphasizes the challenge of ensuring that health literacy approaches are integrated into primary and secondary prevention strategies.

Benard Dreyer of the Roundtable said he is not sure what to do about the confusion about health literacy. It has been defined and discussed; there are the minimalists and then there are the maximalists. At some level there are people who insist it is just literacy; at other levels people see and include the complexity of the health care system. Somehow, he said, those two messages must be put together in some way. It’s not what the provider does but what the patient is taking away from it. Those are two very different things, and that connection is what health literacy is all about at the health system-patient interaction.

In Ratzan’s presentation he said that most of prevention takes place outside the health care system. So the question, Dreyer asked, is how does health literacy play out outside of the health system? Food and exercise are a large part of primary prevention, in addition to immunizations. And that raises the issue of agribusiness and advertising. Just as there have been prevention efforts that emphasized how tobacco companies push an unhealthy product for their own gain, perhaps a similar thing needs to be done with unhealthy food and those who produce and market it, Dreyer said.

Ruth Parker, a member of the Roundtable said that the research and intervention efforts of the past decade demonstrate that what people are being asked to do is really difficult for a number of complex reasons that relate to the environment, the culture, and the tasks of everyday living. What, she asked, is the common ground for health literacy that all can agree on? It takes a number of people from different perspectives coming

together to make sure nothing is left out, that efforts don’t alienate large groups of people, and that there is some understanding of what must be known and done to promote health. Noting that she works in a large public hospital where there are many people with many different needs, Parker said that a simple way of understanding how they are doing would be welcomed.

RADM Slade-Sawyer said that perhaps the focus should not be on communicating the need for good health simply for the sake of health alone, but also because health is the number-one resource needed to live one’s life the way one wants to live. Healthy People 2020 has broadened its focus to include the social determinants of health, examining policies in many domains that contribute to health such as transportation, labor, and environmental domains. But the man in the street may not even consciously understand that there are things he needs to know and do to live his life well. Communicating to these individuals who don’t know what to do and what they need to know is a very big issue. That, Slade-Sawyer said, is the big challenge facing everyone in the field.

Gould agreed that health literacy requires effective engagement of policy makers across the board—agriculture, labor, transportation, and so on. If policy makers from multiple areas can be engaged effectively and can be made health literate about the priority and impact on health of their decisions, enormous progress can be made. Prevention is a combination of policy, education, and program intervention, he said, even in the case of clinical preventive services. It is also important, he said, to have a HEDIS1 measure of quality for prevention.

Isham brought up the Health In All Policies2 approach undertaken by Finland. How might that be applied to what the HHS is considering in its approach to the social determinants of health? Slade-Sawyer said that one of the most important things will be to convince groups working in domains other than health, for example, agriculture, that they do have an impact on health and that it is in their best interests to work with HHS. One of the Healthy People 2020 advisory committee meetings is going to discuss health in all policies and how HHS might move forward with this. Gould said that if the effect of other sectors’ policies on health

_______________

1 “The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) is a tool used by more than 90 percent of America’s health plans to measure performance on important dimensions of care and service.” http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/59/default.aspx (accessed June 17, 2011).

2 Health in All Policies “addresses the effects on health across all policies such as agriculture, education, the environment, fiscal policies, housing, and transport. It seeks to improve health and at the same time contribute to the well-being and the wealth of the nations through structures, mechanisms and actions planned and managed mainly by sectors other than health” (Stahl et al., 2006).

could be measured and demonstrated, that would be a useful tool to use in engaging them.

Will Ross asked how behavior can be modified in the setting of prevention-based interventions. There is a repertoire of interventions from tobacco cessation to obesity reduction that rely on behavior modification, he said, and perhaps there is a tacit assumption that behavior modification would also be playing a role in the actions discussed in the workshop, but it was not mentioned explicitly. Gould responded that getting consumers to understand the risk behaviors that one is trying to change may be a part of the intervention. In that case, one would communicate those risks in the most effective and engaging way possible. However, if the perception of risk is not sufficient or effective for change, one must look at other options. Individuals may not be aware of why they are making the choices they make. But if the environment is created so that the healthy choice or behavior is the default condition—that is, the easy choice—then that is behavioral economics at work. The issue may not be one of consumer understanding and processing in order to make a conscious decision. But, Gould said, no matter how one achieves behavior change, primary prevention is about behavior and is the focus of social marketing campaigns.

Homer said that in the field of pediatrics, practitioners are well aware of the difficulties of prevention and behavior change. One example of this relates to children’s car seats. Pediatricians and family physicians thought they were doing a great job talking to families about risks and benefits and why car seats were such a wonderful thing, but what really changed behavior was the passage of legislation that required car seats. This demonstrates that it is crucial, when talking about health literacy and prevention, to include the need for an informed public that can make policy choices that will influence positive behaviors. Such policies range from absolute requirements, as was the case with car seats, to the creation of default situations that lead one to pro-health behaviors.

Gould pointed out that the seat belt law is another example. There is not a person in this room, he said, who would move his or her car in the driveway without putting on the seat belt because it’s a habit, a social norm. This demonstrates the interplay between engagement strategies and policy strategies, Gould said.

Michael Davis of the Roundtable commented on the idea of a prevention scorecard. Davis explained that General Mills uses a similar mechanism which it calls a health number. The data stay with the doctor and are never used for employment decisions. Once a year, General Mills brings all the salespeople together for a national meeting. They can meet with a nurse for a one-on-one consultation, have blood drawn, and have the 10 factors included in the health number scored. This provides the company

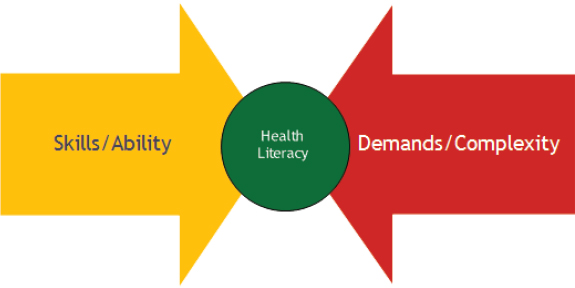

FIGURE 4-1 Health literacy framework.

SOURCE: Parker, 2009.

doctor with an opportunity to create a community health number. Davis noted that if something isn’t measured, it cannot be managed. He said he has been able to see improvement in the salesperson community with this technique. Employees appreciate the chance to meet with a professional and are eager to see how they have progressed or regressed with respect to their goals.

Isham commented on the diagram in Figure 4-13 which was included in Ratzan‘s presentation and in the paper’s discussion of the social determinants of health. Motivation and social determinants of health are important in understanding how individuals act (the yellow arrow in the figure) as well as how to simplify the demands and complexity of the system (the red arrow in the figure). Therefore context or the social determinants of health seem to be key. It seems important, therefore, to begin to focus more on the social determinants of health when deciding how to measure health, Isham said, and he noted that the IOM report, State of the USA Health Indicators (2009) described efforts in this area. Perhaps, he said, one could create a standardized method of measuring health that could be used to engage employers and communities.

Another approach, Isham said, is to look at those health behaviors that are most critical to change. McGinnis and Foege identified these behaviors in 1993 and that study was updated in 2004 by Ali Mokdad.

_______________

3 This diagram was first presented by Dr. Ruth Parker at the Institute of Medicine workshop, Measures of Health Literacy, held on February 26, 2009, and it was published in the summary of that workshop.

But a list of effective interventions to change those behaviors is needed, Isham said.

For clinical preventive services, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force evaluates interventions for their effectiveness. Perhaps, Isham said, a clinical practice guideline that defines the most important interventions in terms of health burden would be useful for health care providers. With developing health information technology, it should be possible to develop decision support systems that take the guidelines into account. The guidelines could also be used to ensure that health professional training focuses on topics and interventions that relate to the behaviors and actual causes of death, Isham said. Then this information could be presented to the public as what should be expected from healthcare providers. The potential to do this is a tremendous opportunity for health literacy.

Isham said that Ratzan’s scorecard idea was a good start toward this goal. Homer responded by emphasizing a developmental approach to prevention. The way that messages are constructed and delivered is important in prevention, he said. Communicating messages to individuals at different stages of the life course (e.g., children, adolescents, young adults, and the elderly) require different strategies, perhaps even different messages. Dreyer supported the developmental approach saying that prevention messages and interventions in childhood and adolescence are key to health at later ages. Isham agreed that thinking about prevention across life stages is critical.

Linda Harris, Roundtable member, noted that health literacy is not static. The discussion, she said, seemed to assume that once a message is perfectly formed, with perfect clarity, that the message will be good forever. It is important, she said, to think about health literacy in the age of such information technology as Wikipedia, in which definitions are changed rapidly, not by professionals and experts at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) but by people who in the past were recipients of messages but who have now become the creators of messages. These social interactions, both mediated and unmediated, are changing the landscape of what health literacy needs to consider, she said. Harris suggested that the Roundtable should examine new media and what they imply for a group trying to present authoritative and clear information.

Dreyer said that several people had mentioned that the education system has a role to play in health literacy but, he asked, what is it that the education system should be asked to do? Slade-Sawyer responded that the Healthy People Curriculum Task Force has been working to introduce public health education into the school system. The effort has been under the leadership of Richard Riegelman, who advances the concept of the

educated citizen. The goal is to integrate health education into curricula from kindergarten through college.

Clarence Pearson, Roundtable member, said that he is concerned about the enormous task of engaging the 14,000 independent school districts in the United States. Homer noted that districts are currently required to have health plans into which health literacy could be incorporated. Introducing the concepts of health literacy into the plans has the potential to improve them. Early childhood education is another area in which health literacy needs to be integrated.

Becky Smith, executive director of the American Association for Health Education, said that the National Health Education Standards K-12: Achieving Health Literacy was established in 1995. The standards identify health literacy skills and abilities as well as assessments for determining how well students have attained those skills. The challenge is how to engage the education community in the health-literacy effort, especially in these difficult economic times. The past two years have seen a decrease in the amount of health education in the classroom. Decisions to eliminate this education have been based on economic choices, not on health choices about quality of life. What, she asked, can be done to engage local school districts, school administrators, school boards, and the Department of Education in supporting health education?

Linda Crippen, a nurse anesthetist, asked whether the group was aware of how few health care providers know about health literacy. For her master’s program, Crippen surveyed health provider coworkers and found that 92 percent of staff had never heard of or been educated about health literacy issues. She emphasized that it will be important to educate providers about health literacy, about communication skills, and about effective ways to teach patients.

Sharon Barrett, Roundtable member, said the assumption is made that people will change behavior because they understand what their health or health conditions are. She reiterated Gould’s point that behavior change, not just increased knowledge, needs to be emphasized. Furthermore, it is important to figure out not only how to get individuals to change specific behaviors, but how to get individuals to focus on their health. Alice Horowitz from the University of Maryland School of Public Health said that education in health literacy and good communication should be integrated into the medical school curriculum from year one all the way through residency.

Ratzan said that one thing that concerns him is illustrated by the saying, “The perfect is the enemy of the good.” Implementing health literacy into prevention strategies cannot and should not wait until we have perfect knowledge about what works. But what can be done now? What are the options for advancing health literacy? Perhaps Healthy People 2020

is a place to start, he said. Using behavioral economics is an option, as is using social marketing. Isham pointed out that there is real opportunity for integration with the six priorities of the National Quality Forum and the National Priority Partnership. These priorities are patient and family engagement, population health, safety, care coordination, palliative and end-of-life care, and overuse.

Isham concluded the session by extending his thanks to Ratzan and the panelists for a stimulating and important discussion.