5

Intersection of Health Literacy and Public Health Prevention Programs

INCORPORATING HEALTH LITERACY INTO THE HEALTHY PEOPLE FOCUS ON THE SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

W. Douglas Evans, Ph.D., M.A.

Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Health Promotion and

Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020

Health literacy is about health equity, Evans said. Those who lack health literacy do not have the same opportunity to achieve health as those who are health literate and therefore improving health literacy can have a significant impact on health disparities. If one thinks of health literacy as social marketing, then social marketing can improve health equity and other social determinants of health. Health literacy has been a high priority in the Healthy People movement and health communication and social marketing are evolving under Healthy People 2020, which offers opportunities for using social marketing to improve health literacy.

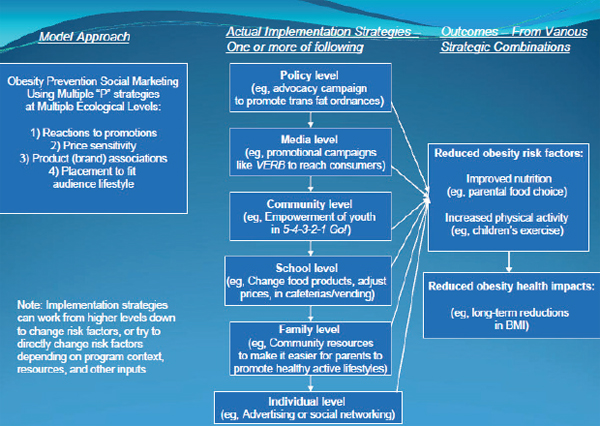

Evans said that social marketing focuses on place, price, product and promotion. When one uses social marketing to improve health, the focus is not only on communication but also on altering the environment to lead to better health outcomes. These strategies align well with the socio-ecological model of health which not only approaches health on an individual level but also considers families, communities, schools and workplaces, as well as media influences and health policies. Childhood obesity prevention efforts, for instance, follow this model by looking at the issue from multiple levels—family, school, and community—with

strategies targeted at each of these levels of a child’s environment. Health literacy can be promoted for its benefits in the same way that healthy eating or not smoking are promoted for their benefits.

What is needed, Evans said, is to build a social movement around increasing health literacy that would be modeled on other successful movements. To make health literacy omnipresent, he suggested building health literacy as a lifestyle brand, modeling the idea that being health literate is desirable. For example, the social environment surrounding tobacco control has changed drastically in recent history and this required more than warnings about shortened life spans and other health risks of smoking. Social marketing techniques that worked at multiple levels helped change the environment to make it harder to smoke in certain locations, to increase prices, to tax cigarettes, and generally to make it more inconvenient to smoke. Social marketing has also helped build breast cancer awareness and prevention through Race for the Cure, a movement that did not exist 25 years ago.

Healthy People has been making strides in refocusing its efforts to include working not only the public health community, Evans said, but also with the many other groups and individuals who are key to improving the health of the U.S. population. Healthy People 2020 is attempting to build a brand around Healthy People in order to reach previously unaddressed audiences such as the general public, very few of whom know what Healthy People is, and in particular, members of groups suffering from disparities who could benefit the most if Healthy People information were made easily accessible to them and if they were motivated to want to actually use it. Evans presented a framework for obesity prevention (Figure 5-1) as an example of a plan that takes into account the socio-ecological mode.

Evans proposed a scenario for building a movement around health literacy. At the policy level, he said, one could develop advocacy campaigns to promote people becoming health literate—for example, by telling people they can become health literate by doing five simple things in their communities. At the community level access points could be provided for people to enact or engage in those behaviors that are being promoted at the policy level. There could be individual- or family-level activities in which families worked together to become more health literate and to realize the potential benefits for the family.

Healthy People 2020 is focused on building health equity by constructing a multilevel approach to health using communication and marketing both to promote stakeholder buy-in and as an intervention strategy. Social marketing interventions can focus on health literacy as a critical health equity issue for the next decade, thereby being a useful strategy for engaging health literacy stakeholders, Evans concluded.

FIGURE 5-1 A framework for obesity prevention.

SOURCE: Evans et al., 2010.

INTEGRATING HEALTH LITERACY INTO STATE PREVENTION, WELLNESS, AND HEALTH CARE PROGRAMS

Linda Neuhauser, Dr.P.H.

Clinical Professor of Community Health and Human Development

University of California at Berkeley School of Public Health

Health literacy is a critical issue, Neuhauser said, and it is clear there are major challenges in improving health literacy. For example, how can health literacy efforts be scaled up so that they have an impact at the population level? What are some of the specific strategies that will lead to success?

As discussed earlier, despite the desired objectives of health literacy promotion, such as those outlined in Healthy People 2020, there is difficulty developing interventions to achieve those objectives. One approach is to advance health literacy through state-level actions. Efforts to improve health literacy could be included in specific laws, regulations and policies, such as those that govern state level health plans or Medicaid. The state level is also a terrific place to educate and develop the champions needed to make health literacy gain traction at a statewide level, Neuhauser said.

Working at the state level also increases access to statewide government budgets, philanthropic organizations that dedicate funds for statewide efforts, health provider and cultural networks, and media.

Neuhauser explained that researchers at the organization, Health Research for Action (HRA), focus on translating research into effective interventions and policy guidance on a variety of topics, one of which is improving health communication. Much of the organization’s work relates to large-scale multimedia communication that is relevant to people’s literacy, language, disability, and cultural needs. Work occurs at local, state, national, and international levels. The organization has identified seven steps that, when applied assiduously, result in effective communication that is much more relevant to the issue of health literacy and that meets people’s needs. These seven steps are as follows:

- Define audiences and communication goals.

- Set up an advisory group composed of users and stakeholders.

- Identify issues from formative research.

- Draft content using health literacy design principles and user input.

- Perform usability tests until it works.

- Simultaneously design implementation plan.

- Evaluate, revise, and extend to other states.

Defining the audience, the first step, appears simple. But in traditional communication one often doesn’t think about the fact that there may be a need to reach and work with a diversity of audiences—not only the patient or consumer, but also providers, politicians, community leaders, and media. One must, Neuhauser said, think about all the different groups that are going to be involved in either facilitating or putting up barriers to efforts to advance health literacy. Therefore, Step 2, setting up an advisory group that includes all these users and stakeholders, is particularly useful. The group members can then become champions of health literacy.

Step 3, doing formative research, is important to ensure that what is developed meets the needs of those for whom it is designed. Using techniques of participatory design, Step 4, to engage the users and stakeholders as collaborators in the development, implementation, and testing of design is key. Finally, conducting usability testing of the information with the potential users and stakeholders until it works (Step 5), simultaneously codesigning an implementation plan (Step 6), and finally evaluating, revising, and extending this to larger geographical areas (Step 7) are crucial to ensuring that one has an effective project and understands how and why it works.

Creation of the California Kit for New Parents, which is a multimedia kit containing DVDs, guide for new parents, and the What to Do When Your Child Gets Sick guide developed by Gloria Mayer of the Institute for Healthcare Advancement (IHA), followed the eight-step process. In developing the kit, the organizers faced the challenge of creating a multimedia, low cost communication tool for the state of California that could reach 500,000 new-parent families effectively and affordably. The kit was distributed at 10,000 different sites including Women, Infants, and Children’s (WIC’s) program sites. The three-year longitudinal evaluation study found an 87 percent usage rate (95 percent for Spanish-speaking new-parent families) and improved parent knowledge and practices. The kit was revised based on the evaluation and has been used as a model for four other states.

Another example of a program developed using these steps is the California Medicaid Access Guide. California has 600,000 seniors and people with disabilities on Medicaid and research shows that many of them do not know what their health care options are or how to navigate the system. Health Research for Action worked with hundreds of people including seniors, people with disabilities, and those who spoke Spanish, English, and Chinese to develop a guide that would work for all of them. The advisory committee included representatives from the state Medicaid office, health plans, consumers, academics, and professional groups. Usability testing was conducted until actual Medicaid users said that it would be effective. The developers won the IHA Health Literacy Award for the guide.

Neuhauser suggested that the Roundtable could focus efforts on statewide initiatives. It would be great, she said, if statewide strategies were included in the National Action Plan. There is also a need to support emerging statewide partnerships in health literacy. There is much that can be done to improve health literacy by including a focus on statewide efforts, Neuhauser concluded.

HOW HAVE THE CONCEPTS OF HEALTH LITERACY BEEN INCORPORATED INTO LOCAL PREVENTION AND WELLNESS PROGRAMS? WHAT ARE THE SUCCESSES AND CHALLENGES?

Jennifer Dillaha, M.D.

Director of the Center for Health Advancement

Arkansas Department of Health

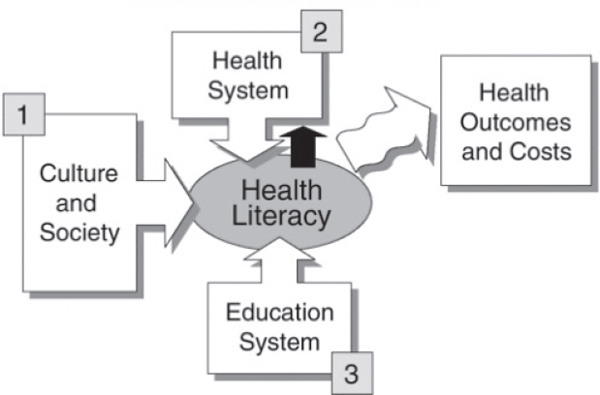

Health literacy, said Dillaha, is a cross-cutting issue that affects all health care improvement efforts. Health literacy is based on the interaction of a person’s skills with health contexts, health care and education

systems, and broad social and cultural factors at home, at work, and in the community.

Arkansas struggles with low health literacy; approximately 56 percent of adults in Arkansas are considered functionally or marginally illiterate. Less than 45 percent of households in the state have access to a computer or the Internet, which presents a challenge to information-based interventions. Arkansas also has a shortage of primary-care providers in a medical system that focuses on tertiary care. This means that, for the most part, primary prevention does not occur in the health care setting. Primary prevention takes place in the community instead, and that is where health literacy efforts should focus. Health literacy requires an ecological approach and Figure 5-2 illustrates the points at which interventions can take place.

Over the past two years, the topic of health literacy has been repeatedly introduced by the Arkansas Department of Health and during that time a groundswell of interest has developed. Various groups and individuals were calling for a meeting to focus on coordinating efforts. On July 24, 2009, a meeting hosted by the health department, the Arkansas Literacy Councils, the University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service, and the Arkansas Children’s Hospital, brought together a broad-based coalition of individuals, agencies, and organizations engaged in

FIGURE 5-2 Potential points for intervention in health literacy.

SOURCE: IOM, 2004.

health literacy—even those that may not have specifically referred to what they were doing as “health literacy.” Because of the large amount of interest, the decision was made to put together a summit on health literacy. Planning for this is under way with ongoing discussions of how to partner with others. It is anticipated that this summit will take place by the end of 2010.

The Arkansas Department of Health is centralized. There are no local health departments but each county has at least one local health unit and Arkansas seeks to provide training on health literacy for these points of contact. The administrators of the units work to engage community leaders and stakeholders in talks about health issues for their communities, facilitating a process by which they examine data in order to make decisions about which issues to tackle. Many of these groups are addressing health literacy issues, even if called by another name.

One effort now under way is the Hometown Health Initiative. a state program intended to develop local capacity to build and maintain community coalitions among health systems, the community, and schools; to develop local capacity for health education services; to promote inclusion of disparate populations in community development; to enhance school-based wellness initiatives; and to strengthen local emergency response. The local coalitions develop and implement their own strategies with state support. Key partners in this effort are the Arkansas Literacy Councils which have a presence in most local areas.

The Department of Health has partnered with the Geriatric Centers of Excellence to implement the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. The six-week program is essentially a health literacy curriculum, Dillaha said, which trains community members in proper nutrition, physical activity, stress management, how to take one’s medicine, how to talk to one’s doctor, and how to evaluate new health information. The course is offered at senior centers and area agencies on aging, although it is not restricted to older adults. Dillaha said that the course has been shown to improve health outcomes for those enrolled.

Other efforts include those of the Area Health Education Centers, which are working to implement a model for the patient-centered medical home and are integrating principles of health literacy into the model. Furthermore, Baptist Health developed a new model for delivering chronic care through home health care. Its weekly care conferences emphasize understanding health literacy issues. Patients of this home-based chronic care model have improved disease self-management.

The Arkansas Department of Health has also established a partnership with the state department of education to implement a wellness program called Coordinated School Health. The program was originally funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention but it

has been able to use tobacco settlement dollars to fund one person to act as a change agent in school districts that wish to implement this model. Additionally, there is a comprehensive K-12 health education curriculum, HealthTeacher, the goal of which is to increase the health literacy of all teachers and students. This program is funded by the Arkansas Children’s Hospital. The three-year pilot program involves 35 school districts with over 270 schools and incorporates an online curriculum that teachers can review and use fully or partly, at their discretion.

Dillaha said that, because increased funding for health literacy efforts is very unlikely, it is important to work with the people who are in place in order to get them to focus a bit of their time on health literacy issues and thus, to turn them into change agents for improved health literacy. It is one thing to understand what is needed, but it is another to have the capacity to take action. System change and capacity building are needed for a state like Arkansas to promote health and well-being, and reduce health disparities through improved health literacy, Dillaha concluded.

DISCUSSION

Ruth Parker, Roundtable member, noted that Evans’ presentation emphasized a Healthy People 2020 focus on equity. But while is it useful to talk about health literacy and branding efforts to improve equity, she said, it is also important to deal with the issues surrounding lack of access to health resources. Many of those who suffer low health literacy also struggle with access. If one tells people to go do something that they can’t do because they don’t have the access and don’t have the ability, Parker said, one is ignoring the realities of the situation. Evans responded that branding and other social marketing efforts are designed to create demand for health literacy. But this must also be done in the context of other efforts that focus on increasing access if the goal is to increase equity because health literacy is an important component of improving equity.

Winston Wong, another Roundtable member, said that the discussion up to that point sounded as if one idea was to aggregate measures of individual health literacy in order to obtain a sense of a community’s health literacy. But, he asked, can one measure community-wide health literacy without aggregating individual measures? Neuhauser wondered if there is an existing model for measuring community-wide health literacy, to which Ratzan responded that World Health Organization’s Healthy Cities project has a longitudinal grant to explore what constitutes a community, which may be a necessary first step. Isham mentioned Nicole Lurie’s efforts using ZIP code level geocoding, but Parker pointed out that the approach still is an aggregate of individuals, not a community score.

With no further suggestions for how to measure community health

literacy, Roundtable member Will Ross commented that health literacy is a social construct that requires collaboration across multiple departments to address, since interventions have to be developed based on the ecological model of health. He asked the presenters to suggest how to pull together the necessary government entities. Evans responded that demand needs to be created, and people need to perceive the benefit. Dillaha said the best model for Arkansas has been to use network management. In this approach a person is designated to meet with key leaders personally to discuss health literacy, get them involved, and get them to the table. Neuhauser added that there is an opportunity to create a set of standards for health communication but this will require a champion. Rose Martinez of the Institute of Medicine referred to Figure 4-1 (see previous chapter) that shows individual skills and abilities on one side and demands and complexities of the system on the other side. She asked Evans what social marketing techniques could be used to engage the system side in health literacy efforts. What can be done to convince those in the system that health literacy is important and that there are things that the system can do to make it easier to help meet the needs of patients? Evans responded that the first question is going to be what the cost implications of such efforts will be. One could, for example, develop marketing strategies and frame messages around reduced cost or managing cost—that is, around the message that health literacy is going to be an effective tool to reduce or manage costs. It is known that people who are health literate are better at managing their own health care, Evans said, but that message is not as widely understood as it could be. Social marketing messages could be developed to persuade health insurers and health plans of the net positive benefit of investing in, promoting, and supporting a health literate population and the community infrastructure that would be needed to encourage health literacy.

Roundtable member Benard Dreyer asked Evans how Healthy People 2020 will be useful for health literacy. Evans responded that the information in Healthy People 2020 is being made available online in a digital database in order to position it as a main source of health information. Dillaha noted that nearly half of the people in Arkansas do not have Internet access. Evans responded that the Internet penetration rate in the United States is approaching 80 percent.

Isham said that each presentation was a different way of looking at improving health literacy. Evans talked about social marketing as a process, Neuhauser talked about communication design principles and involving the end user in developing interventions. Dillaha described a comprehensive strategy to engage multiple stakeholders in approaching the problem in a state with particular needs. All of those approaches are needed, Isham said.

What is also needed is a more detailed systems map for thinking about health literacy, because what works in one area may not work in another, as just illustrated by the exchange between Evans and Dillaha. Evans says that the whole country is going to be on Internet, while Dillaha says this will not be true of Arkansas. A way is needed to figure out what kind of approach is best tailored for the community being addressed and that relates to priorities in communities. For example, health literacy is not a priority in the prevention community. Neuhauser agreed that the time is right to develop a more detailed, public health literacy systems approach. There are many models out there that can be used or linked, she said, however much work remains.

Yolanda Partida, Roundtable member, asked Neuhauser if, in the programs she described, there was an effort made to standardize translation of terms that have no counterpart in the language into which they are being translated. Neuhauser responded that adaptation of materials for different cultural and linguistic groups can require extensive work. For example, no word exists in various Chinese linguistic groups for some items relevant to Medicaid. An entirely new glossary had to be developed. A participatory process was used to develop new terms and to explain those in the materials in a very simple way.

Ratzan said, given the different understandings of what health literacy is, would it help to develop a term for health literacy that is simple and easily understood? Dr. Evans replied that it would be ideal to have a clearer notion of what health literacy is, as it is not entirely understood even in the public health world, and that branding health literacy in a simple way will lead people to demand it. Dr. Dillaha commented that in Arkansas there is no need to generate demand or to convince people they need it. The challenge is to provide them with the skills they need.