Introduction: The Operational Environment

This chapter provides context for understanding how the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) has evolved its approaches to supporting small unit leaders in making decisions and taking action in the operational environments of Iraq and Afghanistan. As the chapter emphasizes, the challenges that Marine small units face in those theaters are not entirely novel, nor are they specific to Iraq or Afghanistan. Instead, they are rooted in a complicated mix of changes and stressors to which the Marine Corps has been adapting since the early 1990s.

As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan reach a decade in duration, adjectives like “hybrid” and “complex” have become standard terms to describe the diverse operational environments in which Marine small units must operate. As discussed below, whether hybrid environments truly represent a new form of warfare is a matter of some debate, but military experts do seem to agree that conflict patterns have become more complicated in the post-Cold War era.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) defines hybrid threats as those “posed by any current or potential adversary, including state, non-state, and terrorists, with the ability, whether demonstrated or likely, to simultaneously employ conventional and non-conventional means adaptively in pursuit of their objectives.”1 In NATO’s assessment, hybrid threats are characterized by “interconnected individuals and groups” that possess the following traits:

![]()

1 U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2010. Hybrid Warfare, GAO-10-1036R, Washington, D.C., September 10, p. 15.

• They are sophisticated users of new communications technologies for purposes of information exchange and collaboration.

• They recognize the strategic value of the 24-hour international media cycle and exploit it to effect particular ends.

• They are agnostic with regard to warfare tactics, employing conventional, cyber, and criminal modes of operation.

• They can adeptly interpret international laws of war to put NATO and other state forces at strategic and tactical disadvantage.2

The NATO Bi-Strategic Command has assessed hybrid threats as one of the most challenging problems of the post-Cold War era, because globalization, the rapid proliferation of new communications technologies, and the expansion of global transportation networks have effectively minimized the traditional significance of geographic and political boundaries.3

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) has similarly recognized the importance of these trends in shaping today’s conflict environments. For example, the National Defense Strategy of 2005 identified “irregular, catastrophic, and disruptive methods” as the hallmark characteristics of war in the 21st century.4 Lacking the resources to match the military capabilities of the United States, adversaries were likely to pursue “complex irregular warfare” instead.5 Similarly, the Marine Corps has asserted the importance of “midrange threat”: violent, transnational extremism and irregular warfare, fueled by economic, political, and social disenfranchisement among growing populations of young adults throughout North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia.6

Interestingly, however, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently pointed out that neither the term “hybrid threat” nor the term “hybrid warfare” has been officially adopted in DOD doctrine, although the word “hybrid” is common parlance among DOD’s civilian and military leadership. In the GAO’s assessment, “hybrid” describes a model of conflict with the following characteristics: it rapidly and unpredictably shifts between conventional and irregular tactics, including criminal and terrorist activity; it can involve both state and nonstate

![]()

2 North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 2010. Bi-SC Input to a New NATO Capstone Concept for the Military Contribution to Countering Hybrid Threats, August 25, p. 3.

3 North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 2010. Bi-SC Input to a New NATO Capstone Concept for the Military Contribution to Countering Hybrid Threats, August 25, p. 3.

4 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, p. 6.

5 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, p. 6.

6 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, p. 9.

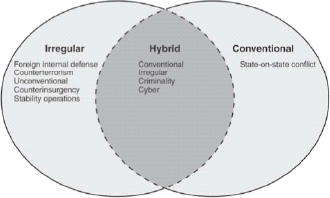

FIGURE 1.1 Conceptual model of hybrid warfare. SOURCE: U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2010. Hybrid Warfare, GAO-10-1036R, Washington, D.C., September 10, p. 16.

actors; and it actively exploits both military and civilian institutions, including the media, to tactical and strategic effect.7 See Figure 1.1.

If there is general consensus about the characteristics of hybrid warfare, there is far less agreement as to the novelty of this form of conflict. According to the GAO, the U.S. Air Force views hybrid warfare as “more potent and complex” than more traditional forms of irregular warfare, whereas the U.S. Special Operations Command, the U.S. Navy, and the U.S. Marine Corps all equate hybrid warfare with full-spectrum conflict.8

It is perhaps more accurate to view hybrid warfare as a blending or blurring of categories that were once treated as distinct rather than as an entirely novel form of warfighting. Certainly the emergence of hybrid conflict patterns does not signal the end of traditional or conventional warfare,9 but it does mean that U.S. military forces must be prepared for a range of conflicts. In these environments, U.S. forces are likely to face “states or nonstate actors [who] exploit all modes of war simultaneously by using advanced conventional weapons, irregular tactics, terrorism, disruptive technologies and criminality to destabilize an existing order.”10 If the destruction of social order meets the strategic ends of the adversary, this implies

![]()

7 U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2010. Hybrid Warfare, GAO-10-1036R, Washington, D.C., September 10, pp. 11-18.

8 U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2010. Hybrid Warfare, GAO-10-1036R, Washington, D.C., September 10, p. 17.

9 Frank G. Hoffman. 2007. Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Wars, Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, Arlington, Va., December, p. 9.

10 Robert Wilkie. 2009. “Hybrid Warfare: Something Old, Not Something New,” Air and Space Power Journal XXIII(4):14.

that maintaining and/or restabilizing basic social, political, and economic infrastructure in the country of conflict is more than a humanitarian responsibility; it is a military necessity.11 As a result, operations in these environments necessarily encompass “all elements of warfare across the spectrum,”12 from active combat to civilian support. Thus, the responsibilities facing conventional and expeditionary military forces are considerable.13 U.S. military leaders have recognized that effective prosecution of the enemy in a hybrid warfare environment requires “a highly adaptable and resilient response from U.S. forces.”14

1.1.1 “The Strategic Corporal” at the End of the Cold War

Over the past decade, USMC leadership has invested significant resources in a rethinking of the conceptual underpinnings of expeditionary warfare and meanwhile has enhanced the operational capabilities of the Marine Corps to meet the conditions of hybrid warfare. However, it is important to note that the investments of the Marine Corps were not made solely in response to conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, even though these conflicts continue to motivate adaptation in the approach of the Corps to its expeditionary mission. Even before the Cold War ended, the landmark doctrinal publication Warfighting acknowledged the dynamism of conflict and the evolution of warfare, calling for the Marine Corps to refine, expand, and improve its capabilities lest it become outdated and stagnant and risk defeat.15 Indeed, the role and responsibilities of Marine small units and their leaders have been evolving since the end of the Cold War, as the Marine Corps has experienced rapid change in both the pace and the nature of its deployments.

As the bilateral nation-state framework of the Cold War disintegrated in the 1990s, latent instabilities erupted into violent conflict in Eastern Europe, Africa, and Central Asia. Driven by long-standing political tensions and differences in economic conditions, the devastating wars that occurred in Somalia, Rwanda, Bosnia, and Sierra Leone (among other locations) were fueled by complex dynamics of identity and ideology. At the same time, the United States, Europe, Japan, and other industrialized countries found themselves facing increasingly significant

![]()

11 John J. McCuen. 2008. “Hybrid Wars,” Military Review LXXXVIII(2):106.

12 U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2010. Hybrid Warfare, GAO-10-1036R, Washington, D.C., September 10, p. 11.

13 Robert M. Gates, Secretary of Defense. 2010. Quadrennial Defense Review, Department of Defense, Washington, D.C., February, p. 8.

14 U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2010. Hybrid Warfare, GAO-10-1036R, Washington, D.C., September 10, p. 11.

15 See Preface by Gen Alfred M. Gray, USMC (Ret.), in Gen Charles C. Krulak, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps, 1997, Warfighting, Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1, Washington, D.C. Also see Gen Alfred M. Gray, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps, 1989, Warfighting, Marine Corps Fleet Marine Force Manual 1, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C.

threats emanating from trans-state criminal and terrorist networks. The most ominous of these was Al Qaeda, which successfully executed a series of devastating attacks on U.S. targets in Yemen, Tanzania, and Kenya in the late 1990s.

In responding to these challenges, the United States drew heavily on the Marine Corps, which has long provided the nation with unique mobility, versatility, and expertise in expeditionary warfare. During the Cold War, the Marines had been called into action once every 15 weeks; in the 1990s, operational demands nearly tripled, and by 1998, Marine units were being deployed roughly once every 5 weeks to locations around the world.16 Most prominently, Marine units supported humanitarian missions in Rwanda and Zaire, played a key role in stabilizing Bosnia after the 1995 Dayton Accords, and responded to the terrorist attacks in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

The Marines drew significant lessons from these experiences, recognizing that operational environments of the post-Cold War era would challenge 20th-century approaches to expeditionary warfare. The 1996 concept paper Operational Maneuver from the Sea, issued under the direction of Marine Corps Commandant General Charles C. Krulak, called for innovation in the “education of leaders, the organization and equipment of units, and the selection and training of Marines” to ensure readiness for the “full spectrum challenges” stemming from ongoing “chaos in the littorals.”17

In assessing the posture of the Marine Corps before the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee in 1998, General Krulak acknowledged a shift from nation-state warfare to complex civil conflict when he described the future of conflict not as “ ‘son of Desert Storm’; it will be the ‘stepchild of Chechnya.’ ”18 Krulak presciently recognized that in these environments, decisions taken at the level of the small unit can have unforeseen implications: “In the 21st Century, our individual Marines will increasingly operate with sophisticated technology and will be required to make tactical and moral decisions with potentially strategic consequences.”19 Moreover, Krulak pointed out, even decisions taken at the lowest level of rank of the Marines were likely to be “subject to the harsh scrutiny of both the media and the court of public opinion,” as new communications technologies facilitated the rapid dissemination of information to an international

![]()

16 House Committee on Armed Services. 1999. The State of United States Military Forces, Hearing before the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, 106th Congress, 1st Session, Publication Number 106-14, January 20, p. 217. Available at http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/security/has020002.000/has020002_0.htm. Accessed October 20, 2011.

17 Gen Charles C. Krulak, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 1996. Operational Maneuver from the Sea, Foreward and pp. 2-3.

18 “Statement of General Charles C. Krulak, Commandant of the Marine Corps, United States Marine Corps, Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on 5 February 1998 Concerning the Posture Hearing.”

19 “Statement of General Charles C. Krulak, Commandant of the Marine Corps, United States Marine Corps, Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on 5 February 1998 Concerning the Posture Hearing.”

audience.20 Whether we like it or not, Krulak argued, the United States is entering the era of the “strategic corporal,” when individual Marines become the “most conspicuous symbol of American foreign policy…. [Their] actions will directly impact the outcome of the larger operation.”21

To position Marines to address these challenges, Krulak ordered the establishment of the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory (MCWL) in 1995 to “study current challenges and analyze future threats affecting the Marine Corps.”22 Located at the Marine Corps Combat Development Command (MCCDC) in Quantico, Virginia, the MCWL was given responsibility for developing and evaluating new operational concepts, including the performance of “Service Oriented Concept-based Experiments” to “test training, organization, and equipment innovations associated with emerging warfighting concepts.”23 As discussed below, the MCWL has played an important role in developing and evaluating new concepts for expeditionary warfare, including “distributed operations” and “enhanced company operations” (ECO), concepts that reflect the significance of Krulak’s “strategic corporal” in today’s hybrid conflict environments.

The listing above is by no means a complete accounting of assessments or activities that the Marine Corps conducted after the Cold War ended. However, it is fair to say that by the time Al Qaeda executed the attacks on September 11, 2001 (9/11), USMC leadership was already anticipating major enduring changes to established paradigms of conflict and examining how the Marine Corps might best address the resulting challenges. Concepts developed in the 1990s are likely continuing to shape the approach of the Marine Corps to the operational environments of Iraq and Afghanistan today.24

![]()

20 Gen Charles Krulak, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 1999. “The Strategic Corporal: Leadership in the Three Block War,” Marines Magazine, January. Available at http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/usmc/strategic_corporal.htm. Accessed October 12, 2011.

21 Gen Charles Krulak, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 1999. “The Strategic Corporal: Leadership in the Three Block War,” Marines Magazine, January. Available at http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/usmc/strategic_corporal.htm. Accessed October 12, 2011.

22 U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory: see http://www.marines.mil/unit/mcwl/Pages/Overview.aspx. Accessed October 12, 2011.

23 U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory: see http://www.marines.mil/unit/mcwl/Pages/Overview.aspx. Accessed October 12, 2011.

24 The conceptual evolution of the USMC is captured in a number of doctrinal publications issued in the late 1990s. Many of the observations and principles included in these publications foreshadow the challenges that the Marine Corps would face on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan. An example appears in the 2001 Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication (MCDP) 1-0, Marine Corps Operations (Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C.). In his foreword to the manual, then-Commandant of the Marine Corps General James L. Jones wrote that MCDP 1-0 “acknowledges that Marine Corps operations are now and will likely continue to be joint and likely multinational … the Marine Corps task-organized combined armed forces, flexibility, and rapid deployment apply to the widening spectrum and employment of today’s military forces.” See also MCDP 6, Command and Control; MCDP 3, Expeditionary Warfare; Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., 1998. Many of these doctrinal publications are available at http://www.marines.mil/news/publications/Pages/order_type_doctrine.aspx. Accessed October 10, 2011.

1.1.2 Facing the Long War

Since the inception of conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, USMC leadership has continued to assess the operational environment and develop strategies for evolving the Corps to meet the challenges of a “pronounced, irregular threat … [that] requires the Marine Corps to make adjustments to the way the Marine Corps organizes its forces to fight our nation’s foes.”25 These assessments emphasize that irregular, catastrophic, and disruptive methods have come to comprise a “pattern of complex irregular warfare”26 that is likely to persist into the future. For example, the 2008 publication Marine Corps Vision and Strategy 2025 identified hybrid warfare as “the most likely form of conflict facing the United States” (emphasis in original),27 while The Long War: Send in the Marines describes a “generational struggle against fanatical extremists; the challenges we face are of global scale and scope.”28

These and various USMC concept papers detail the evolution of the Marine Corps’s foundations and capabilities for ensuring success in the irregular environments of Iraq and Afghanistan. In order to gain a better understanding of how the Marine Corps is positioning itself to address these challenges, the National Research Council’s Committee on Improving the Decision Making Abilities of Small Unit Leaders reviewed some of the publicly available literature in which the USMC leadership describes the steps being taken to ensure that Marines can succeed in hybrid environments.

However, before describing some of these changes, it is important to point out that the Marine Corps is not making adjustments in a vacuum; its innovations are better understood as part of a larger, ongoing process through which the Department of Defense and the armed services have been adapting tactics and strategies to ensure effective coordination of combat and stability operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. These changes have implications for the kinds of activities that Marines pursue as part of expeditionary warfare.

For example, until 2004, DOD military planning guidance identified four phases in the continuum of military operations: Phase 1: Deter/Engage; Phase 2: Seize the Initiative; Phase 3: Decisive Operations; and Phase 4: Transition.29 In

![]()

25 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, p. 3.

26 See also Marine Corps Intelligence Activity. 2005. Marine Corps Midrange Threat Estimate 2005-2015, MCIA-1586-001-05, Quantico, Va., August.

27 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. Marine Corps Vision and Strategy 2025, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, p. 12.

28 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January.

29 Joint Chiefs of Staff. 2001. Doctrine for Joint Operations, Joint Publication 3-0, Washington, D.C., September 10, pp. III-19-III-21.

2004, however, the Office of the Secretary of Defense revised this continuum to include two new phases, one at either end of the established continuum. The new “Phase 0: Shape the Environment” emphasized the establishment and solidification of friendly relationships and the deterrence of potential adversaries. At the other end of the expanded continuum, the new “Phase 5: Enable Civil Authority” directed the military to ensure that civil institutions in conflict zones are properly organized and resourced so that civilian populations have access to functioning public services.30

As the Government Accountability Office pointed out, this expanded operational guidance is playing an important role in articulating types of operations that the U.S. armed forces will be required to pursue in the context of stability operations. In particular, activities comprising the new phases in the expanded continuum are likely to require careful coordination and “significant unity of effort” among the U.S. armed forces, local security and civilian institutions, other U.S. federal agencies, and international coalition forces and partners.31 For example, the challenge of “shaping the environment to confront the underlying conditions that are counter to the prospects of winning the ideological struggle”32 can only be addressed when the U.S. military can work effectively with international coalition partners, international aid groups, other U.S. agencies, and local communities to promote the development of functioning and stable civil institutions in regions of conflict.

Over the past decade, USMC leadership has made a number of changes to ensure that Marines are prepared for these new missions. Among these changes, the Marine Corps has looked to expand force structure, establish new rotation cycles to reduce deployment stress, develop new training programs to provide Marines with theater-relevant skills, and establish new organizations and groups to assist Marines in the field. For example, the Marine Corps evolved some of its core structural elements to enable Marines to pursue new missions and operations. Of particular importance in this regard are innovations in the Marine Air-Ground Task Force, or MAGTF, the organizational structure that is the hallmark of Marine expeditionary warfare. At the battalion level, the MAGTF has traditionally provided “a single commander a combined arms force that can be tailored to the

![]()

30 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, pp. 8-9.

31 U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2007. Military Operations: Actions Needed to Improve DoD’s Stability Operations Approach and Enhance Interagency Planning, GAO-07-549, Report to the Ranking Member, Subcommittee on National Security and Foreign Affairs, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives, May, pp. 14-17. See also U.S. Department of Defense Joint Forces Command, 2006, Military Support to Stabilization, Security, Transition, and Reconstruction Operations Joint Operating Concept, Department of Defense, Washington, D.C., December.

32 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, p. 1.

situation faced.”33 It is a structure that supports the versatile and rapid deployment of force, because it organizes command, logistics, and ground and aviation combat elements into a single structure that can be rapidly deployed into a range of operational environments, either independently or as part of a larger force.

In 2007, the Marine Corps established a new type of MAGTF, the Security Cooperation Marine Air-Ground Task Force (SC MAGTF). Comprising ground, logistics, and air combat elements, the SC MAGTF is organized according to various tasks in the areas of security cooperation and civil-military operations and can provide a range of capabilities, from operational law to veterinary services, even in remote environments lacking basic infrastructure. To enhance SC MAGTF capabilities further, the Marine Corps Training and Advisor Group was created to be deployed in teams of trained advisers, including as part of an SC MAGTF, to provide ongoing security assistance and training and to establish productive relationships among United States, coalition, and local security forces. SC MAGTF staffing requirements also call for officers and noncommissioned officers (NCOs) with academic area studies and language training appropriate for the region of operations.34

Lastly, the Marine Corps has also tried to increase its manpower reserves by growing its number of active-duty Marines. In 2006, the USMC won presidential approval to expand the force structure by 15,000 recruits. This, in turn, enabled the Marine Corps to address the critical problem of deployment fatigue and stress through implementation of a more sustainable deployment cycle, which doubled the ratio of home time to deployment time.35

Yet, the extent to which the Marine Corps will be able to maintain an expanded force, not to mention its trajectory of growth and innovation in training and deployment, is unclear. As public opinion shifts in favor of ending conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States is seeking to reduce its presence in these theaters. In addition, budgetary pressures have driven policy makers to reconsider what is required in order for the United States to maintain a “sustainable” defense capability.36 In January 2011, the Secretary of Defense announced significant cuts in force size that would reduce the number of active-duty Marines from 202,000

![]()

33 Gen Charles C. Krulak, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps, 1997, Warfighting, Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1, Washington, D.C., June 20, p. 55; see also Marine Corps Reference Publication (MCRP) 5-12A, Operational Terms and Graphics; and MCRP 5-12D, Organization of Marine Corps Forces.

34 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, pp. 7-19.

35 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, pp. 13-15.

36 Sustainable Defense Task Force. 2010. Debt, Deficits, and Defense: A Way Forward, Project on Defense Alternatives, Washington, D.C., June 11.

to 187,000 as part of a larger package of proposed efficiencies.37 Reductions in defense spending will undoubtedly continue to impact the Marine Corps.

1.2 DISTRIBUTED OPERATIONS, ENHANCED COMPANY OPERATIONS, AND THE MARINE SMALL UNIT

As the preceding discussion demonstrates, the Marine Corps has been evolving its approach to expeditionary warfare almost continuously since the Cold War drew to a close in the early 1990s.38 In particular, over the past decade, the Marine Corps has invested significant effort into assessing the requirements and demands of its expanding mission space in order to ensure that Marines are provided with the skills, knowledge, and resources required to conduct a full spectrum of operational activities, kinetic and nonkinetic.

Within this context, the committee was charged with examining the challenges facing small units and their leaders in the hybrid conflict environments of the post-9/11 era. The committee was asked to focus on “small units,”39 because in the theaters of Iraq and Afghanistan, units below the battalion level have emerged as key players. Although the Marine Corps has traditionally projected expeditionary force through battalions supported by division-sized MAGTFs, the sheer size of Iraq and Afghanistan, coupled with the need to maintain deployed forces for long periods of time during stability operations, led to much wider distribution of Marine forces. For example, in 2003, I Marine Expeditionary Force (IMEF, comprising approximately 65,000 Marines) completed a 17-day march into Iraq, after which it became responsible for stabilizing Al Anbar Province—

a 53,208 square mile area encompassing more than 1.2 million people living in approximately 40 cities and towns. Marines have had to counter a blend of Sunni insurgents, Al Qaeda terrorists, and local criminal elements in an area which, if it were one of the United States, would rank 26th in geographic size.40

Operational experiences like this are not unique in either Iraq or Afghanistan, and as a result, perhaps the most significant lesson learned over the past decade is the

![]()

37 Robert M. Gates, Secretary of Defense. 2011. “Statement on Department Budget and Efficiencies,” Office of the Secretary of Defense, Washington, D.C., January 6; available at http://www.defense.gov/speeches/speech.aspx?speechid=1527. Accessed October 20, 2011.

38 In a 2009 briefing to the Marine Corps Council, USMC Commandant General James T. Conway identified 10 capabilities and/or organizations that the Marine Corps has created in response to hybrid threats and irregular warfare. See Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps, “Marine Corps Vision and Strategy 2025, Commandant’s Update to the Marine Corps Council,” Powerpoint presentation, April 18, 2009, Slide 21.

39 The Marine Corps considers small units to be at the company level and below. See Appendix D for the organizational charts and size of a typical USMC rifle company, rifle platoon, and rifle squad.

40 Marine Corps Combat Development Command. 2009. Evolving the MAGTF for the 21st Century, U.S. Marine Corps, Quantico, Va., p. 2.

importance of the Marine small unit. Stabilization operations over large areas in which population centers are widely dispersed necessitate the distribution of a division’s forces in smaller units than the battalion—namely, companies, platoons, and squads. In Iraq and Afghanistan, “operations have placed a premium on units with a high degree of mobility and self-sufficiency” while “increasing demand for the ability to employ company-sized task forces in more autonomous roles.”41

Consequently, small units have assumed responsibilities and have been assigned areas of responsibility that were formerly assigned to battalion-sized units. While these changes enabled the Marine Corps to more easily adapt to the fluid tactics of the enemy and to support the protection of indigenous populations, they also put stress on division- and battalion-level resourcing models. In “standard” expeditionary warfare, “subordinate units rely heavily on higher echelons for most of the coordination necessary to accomplish their individual tasks. This works well in situations where communications are easy and units are in close proximity,” but the significant dispersion of forces led to problems with communication, coordination, and mutual unit support.42 In other words, the distribution of forces in Iraq and Afghanistan strained the MAGTF model of force projection—which leads to the topics of distributed operations and enhanced company operations, concepts that represent an acknowledgment of the stresses described here, as well as an effort to capitalize on the agility and adaptiveness of the small unit.

As previously noted, the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory was established by General Krulak in 1995 to look at innovative and unconventional responses to what Krulak had identified as significant changes in future combat environments. Beginning in 2003, in response to conditions in Iraq and Afghanistan, the MCWL developed a concept known as distributed operations, whereby small units would be dispersed across wide geographic areas and connected by robust communications systems.43 The concept was formally articulated in the 2005 concept paper A Concept for Distributed Operations, issued under the direction of Marine Corps Commandant General Michael W. Hagee.44

A Concept for Distributed Operations set out a vision for leveraging “the deliberate use of separation and coordinated, interdependent, tactical actions, enabled by increased access to functional support, as well as by enhanced combat

![]()

41 Marine Corps Combat Development Command. 2009. Evolving the MAGTF for the 21st Century, U.S. Marine Corps, Quantico, Va., p. 5.

42 John D. Jordan. 2011. Improving the Enhanced Company Operations Fire Support Team, Master’s Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, Calif., p. 3.

43 Vincent J. Goulding, Jr., Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory. 2009. “Distributed Operations and Enhanced Company Operations: Experimentation and Marine Corps Capability Development,” presentation to the Zvi Meitar Institute for Land Warfare Studies, Latrun, Israel, September 2.

44 Gen Michael W. Hagee, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2005. A Concept for Distributed Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., April 25.

capabilities at the small-unit level.”45 Underlying the distributed operations concept was the recognition that “the warriors on the ground, the small units, [are] the prime discriminators, deciders, and actors.”46 Arguably, the concepts presented in A Concept for Distributed Operations simply formalized a well-established trend: with resources more widely distributed, and facing a broader range of challenges, Marine small units and their junior leaders (captains, lieutenants, sergeants, and corporals) were in fact assuming responsibility for problems that would otherwise be addressed by more senior officers and NCOs at the company or battalion levels. The concept paper pointed out that multiple deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan had also created a seasoned cadre of junior officers and NCOs who had “proven their critical thinking skills and tactical competence in combat … and [were] demonstrating a capacity for small unit leadership… .”47 By “moving authority ‘downward’ to dramatically increase the speed of command,” distributed operations would allow the Marine Corps to leverage this experience to advance maneuver warfare and “achieve tactical successes that will build rapidly to decisive outcomes at the operational level of war.”48

Yet, as several USMC publications emphasized, the devolution of authority to companies, platoons, squads, and teams would necessitate changes in the preparation and resourcing of these units. Importantly, when small units are distributed, they are “separated beyond the limits of mutual support.”49 Indeed, the distributed operations concept was at first “met with resistance by many due to the vulnerability of small units operating far from supporting units and higher headquarters, and the necessary equipment development and fielding lagged far behind.”50 Yet as MCWL Director Vince Goulding put it, the point of distributed operations was to “enable tactical units to distribute because of their training and equipping, not in spite of it” (emphasis in original).51

As a concept, distributed operations recognized that smaller units, particularly below the company level, needed access to higher-level resources and

![]()

45 Gen Michael W. Hagee, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2005. A Concept for Distributed Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., April 25.

46 LtCol Edward Tovar, USMC. 2005. “USMC Distributed Operations,” DARPA Tech, August 9-11, p. 22.

47 Gen Michael W. Hagee, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2005. A Concept for Distributed Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., April 25, p. 2.

48 Gen Michael W. Hagee, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2005. A Concept for Distributed Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., April 25, p. 2.

49 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, pp. 31-32.

50 Maj Christopher Griffin, USMC. 2009. Enhanced Company Operations in High Intensity Combat: Can Preparations for Irregular War Enhance Capabilities for High Intensity Combat? Master’s Thesis, U.S. Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Quantico, Va., p. 3.

51 Vincent J. Goulding, Jr., Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory. 2009. “Distributed Operations and Enhanced Company Operations: Experimentation and Marine Corps Capability Development,” presentation to the Zvi Meitar Institute for Land Warfare Studies, Latrun, Israel, September 2, Slide 4.

capabilities, either to be “called in” when necessary or embedded “organically” at the level of the unit. Additional air and ground mobility, fire-support elements, technology and training for gathering and exploiting actionable intelligence, a responsive and well-resourced supply chain, support for maintenance problems, improved force protection equipment, and robust communications networks: all of these were identified as critical elements needed to link very small units, down to rifle teams, into an operational whole. Moreover, small unit leaders and their Marines would need training to ensure access to at least some of the technical, organizational, medical, and linguistic skills that are normally provided by specialists embedded in higher levels of command.52

Under the rubric of distributed operations, the Marine Corps made headway in addressing the types of gaps described above. Training was one important area in which the Corps focused resources, to ensure that small units and their leaders had access to the requisite knowledge and skills to pursue important nonkinetic missions, such as conducting training and professionalization activities with local security forces. In 2005, the USMC Training and Education Command (TECOM) established the Center for Advanced Operational Culture and Learning (CAOCL) at Quantico, Virginia. According to USMC documents, CAOCL activities include education, predeployment training, and regional studies to provide Marines with cultural and communications skills for navigating the “cultural terrain.”53 The Center offers instructor-guided and computer-based language training (using Rosetta Stone) to forces being deployed in both Iraq and Afghanistan. In addition, Tactical Language Kits help Marines develop basic proficiency in new languages, and Tactical Language Training Simulation allows Marines to exercise new communications and language skills in simulated deployment encounters. Faculty at the Marine Corps University have also developed curricula on Operational Culture to support Marines in understanding how cultural dynamics can shape military operations. One significant achievement is the publication in 2008 of the Marine Corps University textbook Operational Culture for the Warfighter: Principles and Applications, which integrates historical, economic, political, and social science research with military science and doctrine to help Marines become effective “Cultural Operators.”54 This volume has become a military best-seller, with more than 10,000 copies in print as of this writing.55

![]()

52 Gen Michael W. Hagee, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2005. A Concept for Distributed Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., April 25, pp. VI-IX.

53 Col George M. Dallas, USMC (Ret.). 2008. “Operational Culture: From the Director,” Operational Culture 1(1):1.

54 Barak A. Salmoni and Paula Holmes-Eber. 2008. Operational Culture for the Warfighter: Principles and Applications, Marine Corps University Press, Quantico, Va.

55 Paula Holmes-Eber. 2011. “Teaching Culture at Marine Corps University,” pp. 129-142 in Robert A. Albro, George Marcus, Laura McNamara, and Monica Schoch-Spana (eds.), Anthropologists in the SecurityScape: Ethics, Practice and Professional Identity, Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, Calif.

The distributed operations concept also generated other innovations, including the Squad Fires and Combat Hunter training initiatives;56 the Corps also revised its Infantry Battalion Table of Equipment.57 Experiments conducted by the MCWL also refined the requirements for successful implementation of the distributed operations plan, including better communications devices, target acquisition and long-range precision fire technologies, improvements in logistics and supply chains, and expanded training.58 Research programs, including an initiative of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), were also pursued.59

Yet, in 2008, the Marine Corps announced that the distributed operations concept was “dead.”60 It seems that this decision was made because of the emphasis on increasingly smaller teams being given resources and authority for significant decisions. As one source put it, Marine Commandant General James T. Conway was reportedly “ ‘not comfortable’ with ‘six-man [i.e., rifle] teams going out on their own.’ ”61 However, the concept was not entirely killed. Instead, distributed operations were reconfigured into enhanced company operations, which addressed the perceived “operating environment’s cognitive, physical, and technical limitations that restrained the original [Distributed Operations] concept.”62 The shift from distributed to enhanced company operations was formalized in A Concept for Enhanced Company Operations, issued in August 2008 from the office of Marine Corps Commandant General James T. Conway.63

In contrasting distributed and enhanced company operations, MCWL Director Vince Goulding described distributed operations as a “bottom up approach” to

![]()

56 Members of the committee were briefed on Combat Hunter during the visit to Camp Pendleton, California, in October 2010, and the topic of Combat Hunter training came up in several of the interviews conducted at Quantico, Virginia, in December 2010. More information on Combat Hunter can be found at http://cognitiveperformancegroup.com/projects/projectch; also see http://www.marines.mil/unit/mcbjapan/Pages/2011/110708-hunters.aspx#.Tuljr0rlE1s. Accessed October 20, 2011.

57 Vincent J. Goulding, Jr., Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory. 2009. “Distributed Operations and Enhanced Company Operations: Experimentation and Marine Corps Capability Development,” presentation to the Zvi Meitar Institute for Land Warfare Studies, Latrun, Israel, September 2, Slide 4.

58 Maj Christopher Griffin, USMC. 2009. Enhanced Company Operations in High Intensity Combat: Can Preparations for Irregular War Enhance Capabilities for High Intensity Combat? Master’s Thesis, United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Quantico, Va., p. 4.

59 LtCol Edward Tovar, USMC. 2005. “USMC Distributed Operations,” DARPA Tech, August 9-11, p. 22.

60 Zachary M. Peterson. 2008. “Distributed Ops Concept Evolves into Enhanced Company Operations,” Inside the Navy, May 19.

61 Zachary M. Peterson. 2008. “Distributed Ops Concept Evolves into Enhanced Company Operations,” Inside the Navy, May 19.

62 Maj Blair J. Sokol, USMC. 2009. Reframing Marine Corps Operations and Enhanced Company Operations: A Monograph, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kans., p. 1.

63 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. A Concept for Enhanced Company Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., August 28.

resourcing Marines, recognizing that a “Company is only as good as its platoons, its platoons only as good as its squads, its squads only as good as its Marines.” In contrast, Goulding explained, enhanced company operations emphasize the downward movement of battalion-level functions to the company commander, and he sought to ensure adequate institutional support for the many missions of the company.64

In other words, enhanced company operations formally recognized that the company—not the platoon, squad, or team—“is the smallest tactical formation capable of sustained independent operations.”65 The USMC thus envisions ECO as “driving the full range of combat development activities towards … the company commander.” Identified needs include “[facilitating] improved command and control, intelligence, logistics, and fires capabilities” and further changes to “training, manning, and equipping.”66 The concept paper itself identified intelligence, maneuverability, fires, logistics, information operations, command and control, and expanded training, including new simulations for small units to “rehearse” missions prior to execution. Importantly, the Marine Corps has recognized that increased emphasis on the company as an independent operational unit implies significant potential changes to the MAGTF, including the possible development of “company sized MAGTFs.”67 Evolving the MAGTF to address company operations can include “provision of fires, mobility, logistics, communications, intelligence, information operations, foreign internal defense, and civil-military operations capabilities”68 similar to the capabilities provided at the battalion level, and arguably difficult to source adequately at unit levels much smaller than the company.

To address these challenges, the Marine Corps has redirected effort to pursue the strengthening of company-level capabilities. In particular, the MCWL has conducted several Limited Objective Experiments (LOEs) to evaluate the introduction of critical capabilities to the company level. Prominent innovations that “push” battalion-level capabilities to the company level include the CLIC, or

![]()

64 Vincent J. Goulding, Jr., Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory. 2008. “Enhanced Company Operations: A Logical Progression to Capability Development,” Marine Corps Gazette 92(8). Available at http://www.mca-marines.org/gazette/article/enhanced-company-operations. Accessed July 28, 2010.

65 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. A Concept for Enhanced Company Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., August 28, p. 1.

66 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. A Concept for Enhanced Company Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., August 28, p. 2.

67 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps, 2008, A Concept for Enhanced Company Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., August 28, p. 2; see also LtGen G.L. Flynn, USMC, Commanding General, Marine Corps Combat Development Command, 2009, Evolving the MAGTF for the 21st Century, U.S. Marine Corps, Quantico, Va., March 20.

68 LtGen George L. Flynn, USMC, Commanding General, Marine Corps Combat Development Command. 2009. Evolving the MAGTF for the 21st Century, U.S. Marine Corps, Quantico, Va., March 20, p. 6.

company-level intelligence cell, as well as the CLOC, the company-level operations cell. Between 2007 and 2009, the MCWL conducted an extensive series of LOEs to assess the feasibility and identify gaps in the CLIC/CLOC concepts in different operational environments. In addition, the Corps has continued to leverage resources developed under distributed operations, such as cultural training and language programs and updated equipment.

1.3 CHALLENGES FOR MARINE SMALL UNITS AND THEIR LEADERS

The Long War is indeed a small unit leader’s fight, and we have to make sure our young warriors, operating sometimes with little sleep and in 120-degree heat, are up to the task of making rapid tactical decisions that may have strategic impact.

—Remarks of the Commandant of the Marine Corps,

General James T. Conway, USMC,

“George P. Schultz Lecture Series,”

San Francisco, California, July 2007

In this chapter, the committee has provided a brief and necessarily incomplete description of how expeditionary warfare in the Marine Corps has evolved over the past two decades. The battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan have presented Marine small units and their leaders with a daunting array of missions, including the training and professionalization of local police and military forces, the tracking of insurgents in remote areas, the countering of drug trafficking and interdiction of criminals, the evacuation of noncombatants from conflict zones, even the provision of health care to local populations.69 This diversity is inherent in counterinsurgency (COIN) warfare, which requires Marines to maintain a delicate balance between the use of force and the development of productive relationships with local populations so as to undermine support for insurgency groups (the so-called “hearts and minds”70 element of COIN operations). In Iraq and Afghanistan, Marines are responsible for pursuing and destroying enemy insurgents, while simultaneously protecting civilians, themselves, and their fellow Marines from harm. They are also frequently coordinating their activities with a range of multinational actors, including the multinational teams of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), military and civilian staff from

![]()

69 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January, p. 12.

70 The committee is aware that the idea of operations to win the hearts and minds of indigenous populations is not a new concept. The phrase was first used by the British Army during the Malayan Emergency in 1948, but the concept has been with us since the time of Alexander. It is mentioned here not because it is new, but because it demands skills and sophistication on the part of the small unit leader not normally called for in combat operations.

the United Nations and NATO, and a range of nongovernmental organizations, not to mention local, regional, and national leaders in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The presence of an observant, intelligent, and adaptive enemy presents additional challenges in an already-complicated mission space, because it means that the environment in which Marine small units are performing their missions is unstable and unpredictable. Tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that work well one day may be obsolete the next.

As discussed in Chapter 2, Marine small unit leaders must respond to situations that evolve rapidly and unexpectedly from being calm and productive to being kinetic and extremely destructive. The presence of international news media in the battlefield further complicates matters: not only is 24-hour coverage normal, but also the Internet ensures that news stories about Marine engagements with insurgents and reports of collateral damage to civilian populations can rapidly and easily “go viral” with little warning. The second- and third-order effects of such instances can be significant. Moreover, Marine small units are performing their missions across vast expanses of terrain, in environments that can range from dense urban neighborhoods to sparsely populated mountainous areas.

Basic capabilities, including but not limited to command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR), logistics, intelligence, and fire support, can be difficult to maintain at the small unit level when companies are so spread out. And, despite significant national investments in technologies that are aimed at helping the warfighter, not all technology is available to Marines on the ground, and even technology that is available may not be useful for the missions that Marines are conducting. These missions are inherently challenging, and the Marine Corps is working diligently to prepare and equip its Marines to address them. Yet at the same time, the Marine Corps as a whole must “effectively engage in these operations while still maintaining full spectrum combat capability” (emphasis added)71 insofar as the USMC traditional expeditionary, forward-deployed combat role will remain a core element of U.S. military capabilities into the future. At a Corps level, maintaining excellence across such a diverse spectrum of missions is a significant organizational challenge that inevitably involves long-term strategic planning and resource allocation questions, particularly as budgetary pressures complicate investment questions across the U.S. government.

Finally, at the outset of 2012, the Secretary of Defense provided strategic guidance for the DOD—reflecting the President’s strategic guidance to the DOD; noted among the primary missions of the U.S. armed forces is the ability to conduct stability and counterinsurgency operations. Specifically, “U.S. forces will retain and continue to refine the lessons learned, expertise, and specialized capabilities that have been developed over the past ten years of counterinsurgency

![]()

71 Gen James T. Conway, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. 2008. The Long War: Send in the Marines, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., January.

and stability operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, U.S. forces will no longer be sized to conduct large-scale, prolonged stability operations.”72 Moreover, the strategic guidance continues, counterinsurgency remains important although its emphasis appears to be shifting; however, the complexity of environments in which Marines are likely to find themselves will remain, and improving the decision making abilities of small unit leaders is a long-term proposition regardless of the mission emphasis.

The committee recognizes that these two challenges—preparing the small unit leader for the complexities of an expanding, rapidly changing, and highly uncertain mission space while at the same time maintaining the USMC traditional strengths in expeditionary warfare—are interdependent. In response to the terms of reference for the study (see the Preface), this report focuses primarily on the former: ensuring that small unit leaders are selected, prepared, enabled, and sustained as they assume greater responsibility in complex operational environments.

1.4 ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

With Chapter 1 setting the context for the challenging operational environment of today’s Marine Corps small units, in Chapters 2 through 4, the committee addresses one or more of the topics identified in the terms of reference. Chapter 2 discusses the challenges of the operational environment from the perspective of the small unit leaders. The chapter draws heavily on interviews that a subgroup of the committee conducted in December 2010. The committee had requested permission to conduct these interviews with small unit leaders so that its deliberations could benefit from a fuller understanding of the operational challenges from the perspective of those responsible for carrying out the Corps mission. Coupled with the committee’s meetings and review of Marine Corps literature, these interviews provided observations that helped establish the basis for the set of findings presented at the end of Chapter 2.

Chapter 3 then uses the set of six findings to guide a focused review of relevant and specific areas of science and engineering, from neuropsychology to operations research to decision science, for identifying potential “solution spaces” for supporting effective decision making in small units. From this review comes the committee’s seventh finding as presented at the end of Chapter 3.

Lastly, Chapter 4 draws on the previous chapters in presenting a set of recommendations for operational and technical approaches to supporting, in the evolving operational environment, small unit leader decision making in the Marine Corps. In making these recommendations, the committee recognizes that the Marine Corps has already invested significant effort and resources in the development, testing, and refining of the operational capabilities of the small

![]()

72 U.S. Department of Defense. 2012. Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense, Washington, D.C., January.

unit. The committee is very impressed with the progress that the Marine Corps has made in this regard, and offers its comments and recommendations in support of the Marine Corps as it advances its operational capabilities into the future. In addition, the committee was deeply inspired by the professionalism, dedication, and expertise of the Marines whom committee members met, particularly the small unit leaders with whom the committee had the opportunity to interact. As these women and men perceive, adapt, and very effectively shape the dynamics of complex and dangerous adversarial environments, they demonstrate as small unit leaders why the Marine Corps remains the best expeditionary force in the world.

Appendix A presents biographies of the members of the committee. Appendix B provides a summary of committee meetings and site visits. Appendix C contains a list of acronyms and abbreviations used throughout the report. Additional background information on Marine Corps small units, the committee’s interview protocol, and biomarkers are provided in Appendixes D through F, respectively. A dissenting opinion to Chapter 3 by two committee members is provided in Appendix G.