Nearly everyone experiences fatigue, but some professions, such as aviation, medicine, and the military, demand alert, precise, rapid, and well-informed decision making and communication with little margin for error. Recognizing this, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) added “Reduce Accidents and Incidents Caused by Human Fatigue in the Aviation Industry” to its list of most wanted aviation safety improvements two decades ago. Specifically, the NTSB called for research, education, and revisions to regulations related to work and duty hours. Although regulatory change has received attention in the form of at least two rounds of rule-making activity, there have been no actual changes to relevant regulations since 1985 despite a significantly expanded research base on sleep, fatigue, and circadian rhythms.1

The potential for fatigue to negatively affect human performance is well established. Concern about this potential in the aviation context extends back decades, with both airlines and pilots agreeing that fatigue is a safety concern. A more recent consideration is whether and how pilot commuting, conducted in a pilot’s off-duty time, may affect fatigue during flight duty.

It is important to note, however, that fatigue is not a binary condition in which one is either rested with no negative effects on performance or

___________________

1A Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) with revised regulations on this topic was promulgated in 1995, but it was withdrawn in 2009 with the acknowledgment that changes since 1995 in both the world of commercial aviation and the scientific understanding of fatigue had rendered it out of date. A new rule-making activity was started that resulted in a new NPRM issued in 2010. The committee discusses this FAA rule-making activity related to flight crew fatigue in Chapter 6.

fatigued with severe negative effects on performance. There are degrees of fatigue and degrees of the negative effects of fatigue on performance. Moreover, fatigue is highly variable and is influenced by a number of factors, including amount of sleep, time awake, workload, time on task, and time of day.

STUDY BACKGROUND AND COMMITTEE CHARGE

Concern about the potential contribution to fatigue from time spent commuting to a duty station—known as a pilot’s domicile—increased following a fatal Colgan Air crash in Buffalo, New York, on February 12, 2009. The crash, and the first officer’s cross-country commute, received substantial media attention. The NTSB determined that the probable cause of the accident was “the captain’s inappropriate response” to a low speed condition (National Transportation Safety Board, 2010b, p. 155). The NTSB report identified multiple contributing factors related to flight crew and corporate responsibilities. That report did not list fatigue or commuting as a probable cause or contributing factor in the accident report. Instead, the Board concluded that “the pilots’ performance was likely impaired because of fatigue, but the extent of their impairment and the degree to which it contributed to the performance deficiencies that occurred during the flight cannot be conclusively determined” (National Transportation Safety Board, 2010b, p. 108).

Against this backdrop, in September 2010, Congress, through the Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-216), directed the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to revise its regulations related to work and duty hours to reflect current research. The law also directed the FAA to contract with the National Academy of Sciences, through the National Research Council, to conduct a study of the effects of pilot commuting on fatigue. The Committee on the Effects of Commuting on Pilot Fatigue was constituted to carry out the mandated study, which is intended to inform the development of the commuting-related aspects of the FAA regulations also specified in the act.

The committee was directed to review information in seven specified areas. These areas were (1) the prevalence of pilots commuting in the commercial air carrier industry, including the number and percentage of pilots who commute greater than 2 hours each way to work; (2) characteristics of commuting by pilots, including distances traveled, time zones crossed, time spent, and methods used; (3) the impact of commuting on pilot fatigue, sleep, and circadian rhythms; (4) commuting policies of commercial air carriers (including passenger and all-cargo air carriers), including pilot check-in requirements and sick leave and fatigue policies; (5) post-conference materials from the FAA’s June 2008 symposium titled “Aviation Fatigue

BOX 1-1

Committee Statement of Task

Statement of Task:

Under the oversight of the National Research Council’s Board on Human-Systems Integration (BOHSI), an ad hoc multidisciplinary committee has been appointed to review the effects of commuting on pilot fatigue. The committee will review available information related to the prevalence and characteristics of commuting, literature related to sleep, fatigue, and circadian rhythms, airline and regulatory oversight policies, and pilot and airline practices.

Based on this review, the committee will

- define “commuting” in the context of pilot alertness and fatigue;

- discuss the relationship between the available science on alertness, fatigue, sleep and circadian rhythms, cognitive and physiological performance, and safety;

- discuss the policy, economic, and regulatory issues that affect pilot commuting;

- discuss the commuting policies of commercial air carriers and to the extent possible, identify practices that are supported by the available research; and

- outline potential next steps, including to the extent possible, recommendations for regulatory or administrative actions, or further research, by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

Management Symposium: Partnerships for Solutions;” (6) FAA and international policies and guidance regarding commuting; and (7) to the extent possible, airline and pilot commuting practices.

On the basis of that review, the committee was charged to discuss relevant issues with the goal of identifying potential next steps, including possible recommendations related to regulatory or administrative actions or further research that can be taken by the FAA: see Box 1-1 for the committee’s specific Statement of Task.

The FAA issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) on September 14, 2010—with a broad scope encompassing all aspects of pilot flight, duty, and rest requirements—inviting public comment that would be considered in issuing final regulations (Federal Aviation Administration, 2010c).2 This study is intended to inform the component of those final regulations that are relevant to pilot commuting.

___________________

2The full text of the NPRM is provided at the following link: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-09-14/pdf/2010-22626.pdf [June 2011].

This report describes pilot commuting and the relevant aspects of the aviation industry; reviews current and proposed regulations and nonregulatory approaches to reducing the risk from fatigue; presents the committee’s analyses of input from stakeholders; reviews the scientific literature on fatigue in relation to time awake, time asleep, and time of day; and presents the committee’s findings, conclusions, and recommendations based on the information available during the course of the committee’s deliberations.

The committee produced an interim report, Issues in Commuting and Pilot Fatigue: An Interim Report (National Research Council, 2011). That report described the committee’s work to that date, mapped out the approach to information collection for the final report, and provided a review of the relevant scientific literature and regulatory documents. This report incorporates much of the interim report as background information.3

There is extensive research—including research specific to the aviation industry—on alertness, fatigue, sleep, and circadian rhythms; cognitive and physiological performance; and safety. However, there is very little information specifically on pilot commuting, including commuting practices or airline policies and practices related to commuting. To help address this gap, the committee issued a call for input that was sent to pilot and airline associations and passenger groups and was posted on the project website: see Box 1-2. That call included an invitation to respond to a set of questions specific to the types of information the committee was asked to review: see Box 1-3.

The committee also requested information from 84 passenger and cargo airlines listed as Part 121 carriers by the FAA.4 The airlines were invited to provide input to the study on the relevant topics. The airlines provided a variety of information, including general responses to questions the committee posed, as well as zip code data on pilots’ residences and domiciles (their place of work). In the interests of confidentiality, the companies that responded have been de-identified for data presentations in the report. The committee received written input from 37 airlines, associations, and groups: see Appendix A.

In addition, the committee received input from organizations and individuals interested in providing information, both in writing and in presentations to the committee. All parties who wished to talk with us were included

___________________

3A copy of the report is available for free download from the National Academies Press at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13097 [June 2011].

4Part 121 applies to most passenger and cargo airlines that fly transport-category aircraft with 10 or more seats.

BOX 1-2

Organizations Contacted for Input

PILOT ASSOCIATIONS AND UNIONS

- Air Line Pilots Association

- Coalition of Airline Pilots Associations

- Allied Pilots Association (American Airlines pilots)

- Independent Pilots Association (UPS pilots)

- Southwest Airlines Pilots Association

- Teamsters Local 1224 (Horizon Air, Southern Air, ABX Air, Atlas Air Worldwide [Atlas and Polar Air Cargo], Kalitta Air, Cape Air, Miami Air, Gulfstream Air, Omni Air and USA 3000 pilots)

- U.S. Airline Pilots Association (US Airways pilots)

- International Federation of Airline Pilots Association

AIRLINE-RELATED ASSOCIATIONS

- Air Transport Association

- Cargo Airline Association

- International Air Transport Association

- National Air Carrier Association

- National Air Transport Association

- National Business Aviation Association

- Regional Air Cargo Carriers Association

- Regional Airline Association

INDEPENDENT SAFETY-RELATED ORGANIZATIONS

- Air Travelers Association

- Flight Safety Foundation

at open meetings held in November and December 2010 and February 2011: see Appendix B for the public meeting agendas.

The committee also considered information from the following sources:

- a review of NTSB reports on aviation accidents to identify available information related to the contribution of commuting to flight crew fatigue;

- a review of confidential reports that mentioned commuting or fatigue that were submitted to the aviation safety reporting system (ASRS), a voluntary pilot reporting system;5

___________________

5ASRS is funded by the FAA and hosted by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

BOX 1-3

Topics Posed in Call for Public Input

Interested organizations or individuals were invited to provide comments on their perspective in the following areas, as relevant to their work and experience:

A. the prevalence of pilots commuting in the commercial air carrier industry, including the number and percentage of pilots who commute greater than 2 hours each way to work;

B. the characteristics of commuting by pilots, including distances traveled, time zones crossed, time spent, and methods used;

C. the impact of commuting on pilot fatigue;

D. whether and, if so, how the commuting policies and/or practices of commercial air carriers (including passenger and all-cargo air carriers), including pilot check-in requirements and sick leave and fatigue policies, ensure that pilots are fit to fly and maximize public safety;

E. whether and, if so, how pilot commuting practices ensure that they are fit to fly and maximize public safety;

F. how “commuting” should be defined in the context of the commercial air carrier industry; and

g. how FAA regulations related to commuting could or should be amended to ensure that pilots arrive for duty fit to fly and to maximize public safety.

- a review of the comments related to commuting or fitness for duty submitted in response to the NPRM;

- a review of available information on relevant airline policies and practices in the international arena;

- analysis of data requested from airlines on pilot residence (zip code) and duty location/domicile (zip code) to enable an approximation of linear distance between home and domicile; and

- a review of the relevant scientific literature.

For the purposes of this report, the committee used or adopted working operational definitions for three key issues: pilot fatigue, pilot domicile and home, and pilot commuting.

Pilot Fatigue

There is very strong evidence that fatigue can result in deteriorated performance (see Chapter 4). The Institute of Medicine defines fatigue as “an unsafe condition that can occur relative to the timing and duration

of work and sleep opportunities” (Institute of Medicine, 2009, p. 218). Reported failings from fatigued pilots “have included procedural errors, unstable approaches, lining up with the wrong runway, and landing without clearances” (Federal Aviation Administration, 2010c, p. 55,855). Although it is recognized that fatigue can contribute to aircraft accidents, there is no agreed upon objective measure of fatigue post accident. Therefore, conclusions that fatigue likely contributed to accidents are most often inferred from evaluating sleep-wake history relative to scientific evidence on the causes and consequences of fatigue and, where possible, from review of the cockpit voice recorder. For this study, the committee focused on fatigue that would result from or be mitigated by off-duty activities, particularly those activities related to commuting (e.g., frequency and duration of commutes and opportunities for sleep).

Pilot Domicile and Home

The committee considers a pilot’s “domicile” to be the airport where a pilot begins and ends a duty assignment. This term is distinguished from a “hub,” which is a focus for the routing of aircraft and passengers. A pilot’s domicile may be at one of the airline’s hubs, but it may also be at an airport that does not serve as a hub for that airline.

The committee considers a pilot’s “home” to be the pilot’s residence: it is important to note that it is not necessarily the place where the pilot had the most recent opportunity for his or her customary sleep period prior to duty. The pilot may have access to a hotel room, apartment, or other sleep accommodation near his or her domicile for rest before starting an assignment.

Pilot Commuting

The committee considers pilot “commuting” to be the period of time and the activity required of pilots from leaving home to arriving at the domicile (airport—in the crew room, dispatch room, or designated location at the airport) and from leaving the domicile to returning back to home. Pilot commuting takes place during off-duty hours. Pilot commuting differs from the commuting of other workers in terms of frequency and variability, distance, transport modes, and time of day.

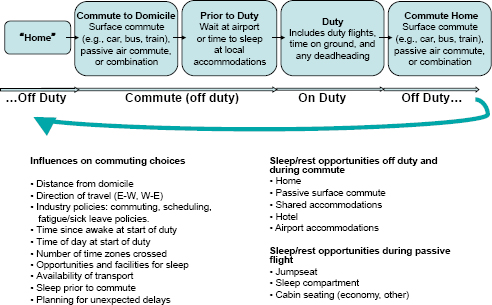

Figure 1-1 depicts pilot commuting in relation to a pilot’s off-duty and on-duty periods. The figure illustrates the complexity of factors that affect a pilot’s commuting choices including opportunities for rest and sleep. There is the potential for tremendous variability across individual pilot commuting practices and day-to-day experiences. This variability results from many influences, not only the duration or distance of the commute. In addition, commuting practices may be subject to further variation when pilots are

FIGURE 1-1 Commuting in relation to duty.

NOTE: The figure maps a pilot’s commuting and duty cycle along a timeline of variable start time and duration, noting the opportunities for rest and sleep and the many influences on commuting. Commuting can be active (driving oneself) or passive (allowing opportunities for rest or sleep). Deadheading (which involves passive traveling by air while on duty) counts toward work time and is not part of commuting.

reassigned to different domiciles with seasonal or economic fluctuations in the industry. In planning a commute, a pilot must consider many things in order to arrive fit for duty such as time of day and time zone at start of duty, availability of seats on commuting flights, affordability and availability of sleep facilities, airline policies, and possible delays. These and other influences on pilots’ commuting decisions are discussed further throughout the report.

The airline industry, the FAA, and other stakeholders have not adopted a uniform definition of pilot “commuting.” Airlines vary in their definitions and some airlines that provided commuting policies to the committee do not formally define it, although these policies are generally intended for pilots who live far enough away that they have to fly to their domicile to begin duty.

The NPRM notes a reference from the British aviation safety agency

(the United Kingdom Civil Agency Authority) to commuting being more than 1.5 hours. In contrast, the FAA advisory circular, on Fitness for Duty, AC-120 FIT, sets a 2-hour threshold (Federal Aviation Administration, 2010c; U.S. Department of Transportation, 2010b). These dividing lines are arbitrary. Distinguishing or characterizing a commute solely on the basis of the duration or distance of commute, or modality of commuting, is overly simplistic. Such an approach may be desired for operational applications, but current thresholds for defining commuting based on time lack evidence-based underpinnings. Commuting matters insofar as it may interfere with fitness for duty. These determinations must be guided by scientific evidence on sleep and fatigue, in both laboratory and operational environments (see Chapter 4).

All commutes, even commutes involving the same amount of time, may not have the same potential to influence fatigue. Some commutes may not be cognitively or physically demanding (e.g., seated as a passenger on a train, bus, or plane), even to the point of permitting sleep to be obtained, while other commutes may entail more physical (e.g., standing) or cognitive (e.g., driving) demands. Also, long distance air commutes that cross time zones have the potential to exacerbate fatigue for a commuting pilot by disrupting the sleep-wake cycle, depending on the time of day, direction of travel, and other characteristics of the flights operated after the commute. Yet, in some situations, the crossing of time zones potentially can mitigate the fatigue from a combined commute and flight duty period.

Pilot Fatigue Management Decision Making

Decision making is central to pilots’ efforts to avoid flying aircraft while they are fatigued. There are three major circumstances in which such decision making has special significance: (1) when the pilot is developing plans for commuting to his or her duty station; (2) when the pilot must make adjustments in plans necessitated by arising contingencies (e.g., bad weather); and (3) when the pilot has to decide whether and how to cancel a duty assignment because of (anticipated) fatigue. The decisions in all such situations are highly challenging. For instance, they typically involve multiple, often conflicting considerations, numerous stakeholders with competing interests (e.g., family members, colleagues, and supervisors), and the need to be informed by nonobvious and sometimes counterintuitive facts about the biology of fatigue and rest.

The structure of this report corresponds to aspects of the committee’s charge. Chapter 2 provides background information on commuting in gen-

eral followed by an overview of the unique characteristics of pilot commuting. The chapter also includes a review of stakeholder comments that were either provided to the committee or obtained through an analysis of public comments submitted to the FAA on the NPRM. The chapter concludes with a discussion of aviation industry characteristics that are relevant to the effects of commuting on pilot fatigue, including airline pilot hiring policies; airline crew schedules and pilot work patterns; airline route networks and crew basing; and competitive and external factors.

Chapter 3 provides background information on aviation safety, including sources of safety improvement, followed by an analysis of information on fatigue-related aviation accidents from reports by the NTSB. The chapter concludes with a discussion and analysis of pilot commuting patterns that exist today.

Chapter 4 provides an overview of the relevant science related to sleep, circadian rhythms, and fatigue. Chapter 5 includes a discussion, followed by illustrative examples, of aspects of pilot commuting that contribute to the risk of fatigue.

The concluding Chapter 6 discusses ways to reduce the risk from fatigue caused by commuting. The chapter begins with background information on the current regulatory context followed by a discussion of fatigue risk management strategies for airlines. The committee’s recommendations are presented at the end of Chapters 5 and 6.

Following the list of references, a glossary and an acronym list are provided. Additional background information, data sources, and analyses are included in the seven appendices. Appendix A identifies the airlines, associations, and groups that submitted documents for the committee’s review. Appendix B provides the agendas for the committee’s open meetings, which list the organizations and individuals that presented before the committee and responded to its questions. The committee conducted a thorough review of all the documents submitted by airlines, associations, and groups as well as a few individual pilots; a summary of its review is included in Appendix C. In addition, the committee examined public comments in response to FAA’s NPRM that related to commuting. Appendix D presents a summary of the analysis of that purposeful sample of public comments. An analysis of scheduled aircraft departures for the third quarters of 2000, 2005, and 2010 is discussed in Chapter 2. The data for this analysis in number of aircraft departures by airline and by city are available in Appendix E for mainline airlines and in Appendix F for regional airlines. Also provided in Appendix E is a list of airport codes alongside the corresponding airports and cities. The final appendix (Appendix G) includes the biographical sketches for the committee members and staff.