2

The U.S. Airline Industry and Pilot Commuting

This chapter discusses characteristics of the U.S. airline industry and the policies and practices that are likely to have an effect on pilots’ commuting choices. This discussion draws on the expertise of committee members, information from stakeholders who provided comments at committee meetings or through the study website (see Box 1-3 in Chapter 1), a review of the comments related to commuting that were submitted to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in response to the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM), and a review of available airline policies.

Commuting is usually defined as travel between home and a work location on a regular basis. A Gallup Poll found that the mean commute in the United States was 45.6 minutes and the median was 30 minutes; overall, about 64 percent of commutes were less than 1 hour while 8 percent were 2 hours or more (Gallup, Inc., 2007). Characterizing a population’s commuting routines is complex at best because of the enormous variation between individuals, as well as the variation for individuals from 1 day or week to another (Lyons and Chatterjee, 2008). Most of the research on the effects of commuting and commuting habits has been conducted in the context of daily routines using ground transportation in large urban areas. Although there are some studies of remote or rural geographic areas and of employees in specific industries, such as shift workers, hospital staff, and miners, there is very little research that examines (or even mentions) the commute of pilots or the airplane as a mode of transport.

The nature of commuting has been changing. In one study of commuting over a 10-year period, half of the sample changed their main method of travel at least once, and one-fifth changed three or more times (Dargay and Hanly, 2003). Several studies have looked at the physiological effects of relatively long car drives (Kluger, 1998); self-reported attitudes in high-congestion conditions (Hennessy and Wiesenthal, 1999); and rail commuting (Walsleben et al., 1999; Evans et al., 2002). A common conclusion across many studies is that unpredictability leads to stress. Unpredictability can be due to unanticipated delays because of traffic volume or weather or the unreliability of services. However, the studies do not examine the extent to which fatigue from commuting would affect subsequent job performance. They also do not make comparisons across modes of transport. There is insufficient research as to whether a 90-minute car drive is more fatiguing than a 90-minute train ride or a 90-minute plane ride.

There is a body of literature looking at the positive effects of travel (Mokhtarian and Solomon, 2001; Bull, 2004; Lyons et al., 2007; Jain and Lyons, 2008). These include a physical and cognitive break between activities at home and those at work and time to do other activities. Some activities—such as reading, writing, or rest—are only possible in passive modes of transportation, such as trains, busses, limousines, and airplanes. But even active modes of transportation, such as driving one’s own vehicle, can provide time to think, to listen to an audiobook or music, to admire the landscape, and to engage in conversation with companions. The value of these activities depends on individuals’ preferences and other demands on their time.

Commuting is different in aviation than in most other industries. For many pilots, commuting is not a daily occurrence, as pilot duty assignments often extend over several days and keep pilots away from home for multiple days at a time. As a result, a pilot’s commute to work may be undertaken as infrequently as once or twice per month—or more frequently, depending on the flying schedule and commuting arrangements. Pilots sometimes travel to arrive near their domicile (the location of the airport from which they fly) for a period before they are scheduled to fly for logistical reasons or to have a rest opportunity. This rest opportunity may be of a length and quality varying from a nap in a chair to a full night’s sleep in a hotel room or apartment.

It is not uncommon for pilots to travel by air to and from their flight assignment. Pilots commute by air to some extent because they can, and to some extent because they want to: like many Americans, pilots’ planned commutes depend on a host of personal and professional decisions involv-

ing family, economics, and logistics. Commuting by air enables pilots to live a considerable distance from their domicile and travel to work in a relatively short time.

Pilots who provided input for this study told the committee that their commute is influenced by both economic and lifestyle considerations. In the comments the committee received from pilots, half or more of those who addressed the reasons for commuting by air, cited the high cost of living in the area of their domiciles, frequent domicile closings and the future unpredictability of domicile changes, and a desire to maintain family stability. A pilot may choose a community of residence outside of the domicile area because of cost of living near his or her assigned domicile. A home community may be selected based on such quality-of-life factors as a desired geographic region, proximity to a school system, or the existence of a support infrastructure for family while the pilot is on extended flight duty. Commuting by air also enables a pilot to maintain a stable residence if he or she is reassigned to another domicile. One of the respondents to the NPRM expressed similar sentiments:

Commuting is common in the airline industry, in part because of life-style choices available to pilots by virtue of their being able to fly at no cost to their duty station, but also because of economic reasons associated with protecting seniority on particular aircraft, frequent changes in the flight crew member’s home base, and low pay and regular furloughs by some carriers that may require a pilot to live someplace with a relatively low cost of living. (quote pulled from public comments in response to FAA’s NPRM, see Appendix D)

The key issue for safety is whether a pilot begins the subsequent duty rested and fit to fly regardless of how the pilot commutes to work.

Although some pilots live at or close to their domiciles, other pilots live in a location that has never been a company domicile, maintaining a consistent residence as their assigned domicile changes from one airport to another. Some commutes may be a legacy of previous domicile closings or changes, in which pilots who once lived near their assigned domiciles must then commute in order to maintain roots in their original home communities. A point frequently made to the committee was that commuting choices, including the availability of travel by air, can provide pilots and their families an aspect of certainty and control when facing or considering the likelihood of mergers, domicile changes, furloughs, and the like, even when considering these as potential disruptions in the future. A pilot’s domicile may also change as that pilot’s career progresses and the pilot flies progressively larger aircraft, first as a first officer and then as a captain.

Flexibility in commuting choices provides benefits for pilots, but it also provides benefits for the airlines. As discussed below, the U.S. airline

Benefits for Pilots

Stable residence for family

Family residence selected for quality-of-life factors

Low cost of living or low tax jurisdiction location

No need to relocate to progress in career

No need to relocate for domicile changes for industry competitive reasons

Benefits for Airlines

Ability to adapt quickly to changes in flight patterns because of changes in market

No need to require pilots to live near domicile

No need to pay relocation expenses for pilots for domicile change

No need to pay cost-of-living adjustments for domicile change

Benefits for Passengers/Consumers

Potential lower cost services and lower prices

industry has undergone changes in structure and in the pattern of flights during the last decade. Having pilots able to commute longer distances to their domiciles rather than requiring them to live nearby may allow the industry to change flight patterns more quickly to respond to changing market demands. Since, for most airlines, pilots are not required to live near their domiciles, the airlines typically do not pay for pilot relocation or for cost-of-living adjustments when pilots move from one domicile to another. Airline passengers may benefit since airline costs are lower and, in a competitive market, lower costs tend to lead to lower prices for consumers. Box 2-1 summarizes the benefits of commuting for pilots, airlines, and consumers.

As described in Chapter 1, requests for input data were sent to a variety of different stakeholders in the airline industry (see Box 1-2 in Chapter 1).

Because of the extremely short turnaround (a few weeks) between the requests and the committee meeting, the response rates were relatively modest. As of March 23, 2011, the committee had received responses from 25 airlines (4 mainline passenger carriers, 8 regional passenger carriers, 9 cargo carriers, and 4 nonscheduled charter carriers), 2 of the airline associations, and 2 of the pilot associations. The committee’s review of the responses is

summarized below and detailed in Appendix C. (Some airlines responded with written input after this date, and their input was considered for this report, but it is not included in the summary of stakeholder response in Appendix C.) The committee also received written statements from three individual commercial pilots who volunteered their thoughts on issues being addressed by the committee.

The committee also reviewed public comments related to commuting submitted in response to the NPRM. The public comments were purposefully sampled to select those that would be most relevant to definitions of pilot commuting and perceptions of commuting practices. Using the FAA’s electronic database (a total of 2,419 submissions), relevant comments were identified using key terms: “commut”; “commute”; and “commuting” (N = 176). From these, a total of 85 comments, representing remarks from 85 different individuals or organization representatives, were deemed relevant and selected for qualitative analysis. In many cases, an individual comment contained multiple viewpoints of relevance (e.g., the commenter’s own definition of commuting and an opinion on the prevalence of commuting practices with some suggestions for the NPRM). As a result, more than 400 viewpoints of relevance to the study were considered. Appendix D presents a summary of the analysis of the purposeful sample of public comments submitted in response to the NPRM.

Both of these reviews of stakeholder input have limitations that must be considered in interpreting the findings. Neither of these analyses is based on representative samples. In the case of the stakeholder input requested by the committee, individuals or organizations from targeted groups provided input based on an open-ended set of questions or, in a few cases, offered unsolicited input on the study topic. In the case of the review of public comments to the NPRM, respondents were invited to provide feedback on all aspects of the NPRM, and this analysis took into account a selection of comments that were relevant to commuting. The response sample, in both cases, is self-selected. The reader is urged to remember that the views reflected in these analyses represent those individuals and organizations that were motivated to provide input to the committee or feedback in response to the NPRM. Thus, it is difficult to know, or even estimate, the extent to which different results would have been obtained from a larger and more representative sample of the stakeholder population. For those that responded to the requests, it is difficult to know whether each respondent understood each question or request as intended. The reader should also note that not all respondents responded to every question, issue, or request. In addition to self-selecting whether to respond, respondents self-selected the questions or topics to which they responded.

One important initial finding from both of these reviews is that there is no clear, consistent definition of pilot commuting in the airline industry.

There are reports of difficulties in estimating the number of pilots who commute by air or who commute relatively long distances or durations as well as any other types of commuting patterns.

Respondents did offer a wide range of factors that influence pilots’ commuting decisions. In order of reported frequency, from high to low, they included high cost of living near the domicile location; frequent domicile closings and future unpredictability of the airline industry; cost and availability of adjunct sleep accommodations; desire to maintain family stability; low pay, especially for regional carriers; lifestyle preferences (e.g., for good weather and outdoor living); and absence of adequate coverage for costly moving expenses. In the aggregate, respondents acknowledged that commuting is a potentially fatiguing activity, but they also commented that commuting conducted responsibly would not necessarily increase fatigue levels significantly. In regard to policies and regulations that might influence commuting practices, the responses were mixed and diverse, ranging from opinions that current policies and practices are appropriate to suggestions for airline ownership of and FAA regulation of factors relevant to commutes and fatigue (e.g., availability of jumpseats and rest accommodations).

AVIATION INDUSTRY CHARACTERISTICS

Characteristics of the aviation industry that influence pilot commuting include airline pilot hiring practices, crew scheduling practices (at many airlines a joint outcome of management decisions and collective bargaining negotiations); route network and crew basing practices; and competitive and passenger demand factors that can cause pilot staffing requirements to change over time. These characteristics also influence pilots’ preferences related to commuting and their decisions about where to maintain their homes. Also, some airline policies and practices can facilitate or impede a pilot’s ability to commute, with the potential for affecting not only the pilots’ choices of whether and how to commute; but also whether they experience fatigue related to the commute and whether they may operate flights in a fatigued condition.

Airline Pilot Hiring Policies

Pilots compete for positions at airlines in an international market for their services in which the supply of pilots in most years has exceeded the demand from a relatively small number of employers. The sources of trained and qualified pilot candidates (primarily, universities, flight schools, the military, and smaller operators) are geographically diverse. The committee did not have information on the percentages of pilots from each source. In the United States, pilots taking entry-level positions at regional airlines

have tended to earn lower wages than pilots at mainline carriers. In many cases, pilots who join a regional carrier hope to change employment to a mainline carrier after they have accumulated additional flight experience. Recent contractions and consolidations among several of the mainline airlines and changes in the mandatory pilot retirement age have arguably reduced the outlook for positions at mainline carriers. The tradition in the U.S. airline industry is for the company not to pay for a newly hired pilot’s moving expenses or to require that the pilot live at the domicile. As a result, many newly hired pilots may have both the capability and incentive to begin long-distance commuting. Once established, this pattern may continue through subsequent domicile changes as the pilots attempt to maintain a consistent residence.

Airline Crew Schedules and Pilot Work Patterns

At most airlines, labor agreements between pilots and airlines establish specific policies and practices regarding flight crew scheduling (within limitations for flight and duty time as established in the Code of Federal Regulations). Virtually all of these airlines rely on a bidding process to award monthly schedules (sometimes called lines or blocks) to pilots; selection advantages are given to pilots on the basis of seniority. Typically, a monthly schedule consists of multiple assignments of trips (sometimes called pairings), each of which may consist of several flights over a period lasting 1, 2, or up to more than 6 days. Each of these trips begins and ends at the pilot’s domicile (there also may be one or more overnights elsewhere) and thus comprises the basic duty assignment to and from which the pilot commutes.

By federal regulations, airline pilots are limited to fly no more than 1,000 hours per year, or an average of about 83 hours per month. On the basis of this monthly limit, the number of flight hours per trip will determine the number of trips—and thus, potentially, the number of commutes—during the month. For example, if each of a pilot’s trips involves 20 hours of flying over 4 days, the pilot will do about four of these trips per month for 80 hours of flight time. There will be one or more days off between each trip during which a pilot may elect to commute home.

Using the seniority-based bidding process, pilots select the desired trips and days worked given their individual preferences, including the nature of their commutes. For example, a pilot who commutes by air from home to the domicile may bid for the monthly line of four, 4-day trips; preferably, trips beginning at the domicile late on the first day (allowing for an inbound commute that morning) and ending back at the domicile relatively early on the fourth day (allowing for a homebound commute that evening). This pilot will make four commutes during the month. In contrast, a pilot who

lives near the domicile (e.g., a drive of 45 minutes to the airport) may bid for 10 1-day trips, each of which starts early in the morning and returns to the domicile later that day after 8 hours of flight time. This pilot will make 10 commutes during the month to accumulate 80 hours of flight time. Note that in this example the 1-day trips have more flying time per day, on average, than the 4-day trips in the previous example. The pilot living near the domicile will likely work fewer days to accumulate the 80 flight hours for the month; the pilot with a long distance commute will have more work days and fewer days off to accumulate the same number of flight hours.

Airline Route Networks and Crew Basing

Decisions that airlines make about aircraft routings, crew schedules, and crew basing can affect pilots’ commuting incentives. The point from which a pilot begins duty (typically his or her domicile, with the exceptions noted below) is influenced by airline management practices that vary in the industry. For example, many scheduled airlines—those that operate on specific routes at established times—operate a hub-and-spoke route network in which many flights converge on one airport (the hub) at about the same time so that passengers and cargo can connect conveniently to a flight that is going to the ultimate destination (a spoke). Either a hub or a spoke city could be a pilot’s domicile.

Basing pilots at a hub can be attractive for airlines from the point of view of scheduling flexibility and for exchanging crews during connecting operations in the midst of an operating day. Even in a hub-and-spoke system, though, many airplanes are positioned at the spoke airports overnight, and basing pilots at a spoke airport can reduce the expenses of providing overnight accommodations (“overnighting”) for the pilots who work the originating and terminating flights of the day. In any case, the scheduling and routing of crews does not have to match that of the aircraft. For airlines using domicile basing, whether located at a hub, spoke, or elsewhere, the airlines typically leave the pilots responsible for performing the commute—by whatever modes and means necessary—so as to be at the domicile reliably on time and ready for duty. By requiring its pilots to be ready to fly at any domicile, operators are able to select domiciles that minimize the overall costs of staffing the airline, in addition to other factors.

In contrast to the practices of most major scheduled airlines, other airlines (most commonly those offering nonscheduled service1) operate flight patterns in which their airplanes may be routed in a highly variable manner in accordance with customer demand, rarely returning to a specified base. Given this aircraft routing it may be most efficient to dispatch flight crews

___________________

1Nonscheduled airlines operate on customer demand without a regular schedule.

directly from their homes to wherever the previous crew left the airplane. Many of these airlines, consequently, have no established pilot domiciles. In these cases there may be at least a shared responsibility between the company and pilots for the trip from home to the first flying assignment. In one variant of these practices, home basing, there is effectively no commute because the pilot’s on-duty work period begins and ends at his or her home. All of the travel to and from the pilot’s operational flying is scheduled by, and the responsibility of, the company. As on-duty travel (as distinct from commuting travel), depending on the timing of the flights and as required by regulations governing flight time, duty time, and rest, the company may be required to provide adequate facilities and time for rest between the positioning flight to the duty location and the pilot’s first operational flight. In another variant, gateway basing, the company establishes a number of gateway airport locations and assigns the pilot to the gateway nearest his or her home. Pilots are then responsible for commuting between their homes and the gateway, while the companies are responsible for on-duty travel between the gateway and wherever in the world the pilot’s first operational flights will begin and end.

Competitive and External Factors

The dynamic and evolving structure of the airline industry affects the environment in which pilots make commuting decisions. Some airlines’ responses to a changing competitive environment have involved establishing new hubs and downsizing or closing existing hubs and starting service to cities they previously did not serve or ending service to some cities. Airline mergers and acquisitions have also led to downsizing or elimination of hubs believed to be redundant in the postmerger route structure. Seasonal scheduling can cause other complications and may result in changes in pilot domiciles to accommodate increased or decreased passenger demand for particular routes.

These changes in flight patterns may lead to domicile expansions, contractions, closings, or openings, with concomitant changes to where a pilot is domiciled. Changes in domiciles are handled, typically, through seniority-based bidding: pilots with relatively less seniority may sometimes be involuntarily displaced to new domiciles in other parts of the United States (or even other parts of the world), or, in the extreme, furloughed from the company. Subsequently, recalls from furloughs in response to increases in travel demand may result in pilots being recalled to a domicile that is different from the one from which they were released. Other major disruptions to pilot employment have occurred as airlines have reorganized their fleets and route systems under bankruptcy protection or even ceased operations and liquidated; other employment opportunities for pilots have

developed, often at different domiciles, as new entrant airlines have begun operations.

Changing Service Patterns in the U.S. Airline Industry

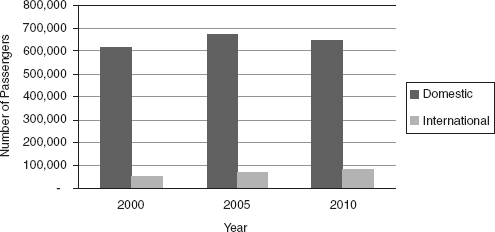

Figure 2-1 shows the number of passengers carried by U.S. airlines in both domestic and international service in 2000, 2005, and 2010. International traffic increased throughout the period while domestic traffic increased between 2000 and 2005 then decreased in 2010, largely because of changes in the economy. Aggregate traffic statistics for the U.S. airline industry do not show some of the important changes that have occurred over the last decade in both industry structure and service patterns. Throughout the past three decades following airline deregulation, new airlines have entered the market, some airlines have grown, others have gotten smaller sometimes as part of a bankruptcy restructuring, and still others have ceased operations.

Two kinds of changes in the U.S. airline industry over the past decade are particularly notable in their potential to affect pilot commuting patterns: the rise of regional jet service, and mergers. An important industry change that could affect pilot commuting is the rise of the regional jet industry and the extent to which regional jet service operated under contract to mainline carriers has replaced service in larger jets operated directly by mainline carriers. The rise of the regional jet industry is a relatively recent development (see Oster and Strong, 2006). In 1995, there was no regional

FIGURE 2-1 Passengers carried by U.S. airlines.

SOURCE: Derived from data, used with permissios, from Air Transport Association of America, Inc. (2011).

jet service operating from the hub airports of the mainline carriers. By 2000, such service accounted for 16 percent of aircraft departures, and in the next 3 years such service had grown to 38 percent of aircraft departures from hub airports. In that 3-year period, domestic departures from hub airports by mainline carriers declined 18 percent while departures from those hubs by regional airlines under contract to the mainline carriers increased 250 percent, so that combined departures by mainline carriers and regional jets increased by more than 11 percent. Although some of this regional jet service was on routes that had not previously been served by the mainline carriers, much of the service was a replacement of mainline jet service by regional jet service.

The growth of regional airlines at the expense of mainline airlines may change the overall pilot commuting patterns in the airline industry if the commuting patterns of regional pilots are markedly different than those of mainline pilots. Without examining the commuting patterns of pilots in these two industry segments, however, it is not possible to determine even the direction, let alone the magnitude, of such changes. One possibility is that regional pilots might on average commute longer distances than mainline pilots because of the lower salaries regional pilots generally earn, which could make them less able to live close to their domiciles if those domiciles were in areas with a high cost of living. Another possibility is that regional pilots might on average have shorter commutes because the service they provide is more likely to be shorter haul service providing feed to longer mainline flights at the mainline airline’s large hub. In a service pattern such as this, a regional pilot is more likely to begin and end the flight sequence each day at the same hub airport, unlike a mainline pilot, particularly a mainline pilot who may have multiday international flight sequences and therefore begin and end days while on assignment at multiple hubs.

Airline mergers were not uncommon prior to airline deregulation in 1978, but the pace of mergers and resulting industry consolidation picked up considerably in the 1980s. Most of those mergers were among relatively small airlines or were the result of large airlines merging with (or acquiring) smaller airlines. However, several of the more recent mergers since 2000 have involved large established carriers. Notable among these was the merger of American and TWA in 2001; the merger of US Airways and America West in 2005; the merger of Delta and Northwest in 2009; and the merger of United and Continental in 2010. As is discussed below, such mergers have the potential to change pilot commuting patterns because they often involve reducing the flight activity at some of the premerger hubs. In addition to the effects of hub expansion and contraction, mergers can bring changes in domicile assignments as pilots from the premerger airlines bid for new opportunities (crew positions and aircraft types) across the changed array of domiciles of the new (merged) airline.

Another recent trend has been mergers and industry consolidation among regional airlines. Notable among these mergers have been the merger of Republic Airways, Shuttle America, and Midwest Airlines in 2005 and 2009; the merger of Skywest, Atlantic Southeast, and ExpressJet Airlines in 2005 and 2009; and the merger of Pinnacle Airlines, Colgan Air, and Mesaba Airlines in 2007 and 2010. Since these regional airlines typically operate under contract with mainline airlines, it remains to be seen how much effect, if any, these regional airline mergers will have on pilot commuting patterns. To the extent that mergers in the regional segment of the industry result in large regional airlines that operate under contract with multiple mainline carriers that operate hubs in different parts of the country, the mergers have the potential to change commuting patterns by regional pilots as pilots assigned to one mainline carrier’s hub are assigned to a different mainline carrier’s hub.

Departure Changes

Changes in the number of aircraft departures have the potential to affect pilot commuting patterns, particularly when those changes are at the airports most frequently served by an airline and likely to serve as pilot domiciles. If an airline is experiencing growth in departures at an airport, then more pilots are likely to be domiciled there, and pilots who were previously domiciled elsewhere might find their best duty cycle options at that airport. Conversely, if an airline is reducing its departures at an airport, then it is possible that pilots who have less seniority may be furloughed and those more senior pilots who remain might find their best duty cycle options at a different domicile. If pilots perceive that the industry structure and service patterns are likely to continue to evolve and the demand for airline travel likely to continue to be subject to fluctuating economic conditions, they might choose not to relocate their residences each time their domicile changes.

Pilots’ Careers

It is important to recognize that there can be pilot domicile changes even when airline service patterns are stable. In many airlines, a pilot’s career progression involves moving from smaller to progressively larger aircraft as a first officer and then becoming a captain and again moving from smaller to progressively larger aircraft. In many airlines, the mix of aircraft sizes will differ across their hubs. International service, for example, is typically conducted in large aircraft, so a hub that serves as a base for international service may have a higher proportion of large aircraft than another hub that serves predominately domestic routes. Thus, even in the

absence of changes in service patterns, a pilot may change domiciles as part of a normal career progression.

The committee was unable to obtain any systematic information about how frequently pilots experienced domicile changes or how such changes altered pilot commuting behavior. To try to gain some insight into some of the industry changes that might alter commuting behavior, the committee conducted an analysis of changes in the number aircraft departures, by city, by airline, in the cities most frequently served by that airline and thus in the cities most likely to serve as domiciles for pilots.

The data used for this analysis were scheduled aircraft departures taken from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics (n.d.-a). The data were from the third quarters of 2000, 2005, and 2010. All 30 carriers who reported more than 20,000 aircraft departures in the third quarter of 2010 were examined; there were 12 mainline airlines and 18 regional airlines. Two of the airlines were all-cargo airlines, FedEx and UPS, and the rest were passenger airlines. Summary statistics for each mainline airline are presented in Appendix E and for each regional airline in Appendix F. The statistics presented are the total number of aircraft departures in 2000, 2005, and 2010 and the number of aircraft departures for each year by city for each city that was one of the top 10 cities in terms of aircraft departures for that airline in any of the 3 years. For carriers involved in mergers, if the carrier reported data in 2010 as a single carrier, as was the case with Delta, US Airways, and American, the premerger data were combined as if the carriers had been merged in all three time periods. If the carriers involved in the mergers reported data separately in 2010, as was the case with United and Continental, then the carriers were treated separately throughout all three periods.

Rise of Regional Jets

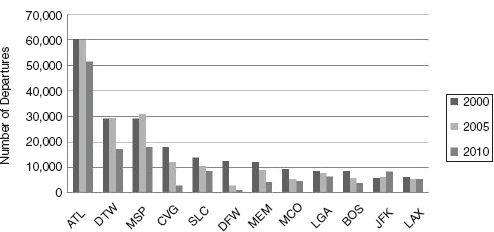

In examining the data, it quickly becomes apparent that the role of affiliated regional carriers has a large impact on mainline service patterns. Three of the mainline carriers, Southwest, Air Tran, and JetBlue, do not use affiliated regional carriers, and all showed growth in departures throughout the period. The remaining mainline airlines, which do use regional affiliated airlines, all showed declines in aircraft departures throughout the period. Both Air Tran and JetBlue are relatively new and small carriers that had comparatively few departures in 2000 and showed strong growth in 2005

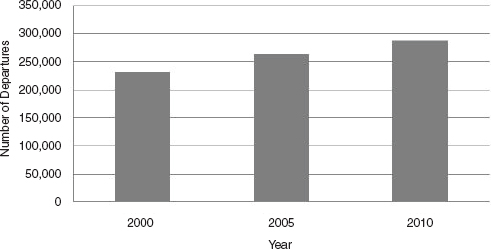

FIGURE 2-2 Southwest total departures.

SOURCE: Data from Bureau of Transportation Statistics (n.d.-a).

and 2010. Both also showed strong growth in departures at their primary hubs, Atlanta for Air Tran and New York’s Kennedy Airport for JetBlue.2

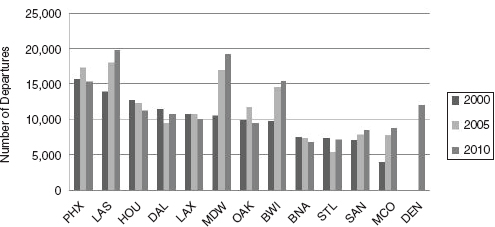

Southwest is a much more established airline than Air Tran and JetBlue and had the most domestic aircraft departures in 2010 of any U.S. airline. Southwest showed steady increases in departures over the period (see Figure 2-2), and it did not experience sharp decreases in departures at any of its primary cities (see Figure 2-3). There were small drops in several cities and somewhat stronger increases in Las Vegas, Chicago Midway, and Baltimore, as well as significant new service established in Denver. Although these changes in departures reflect changing service patterns, they are not the dramatic changes that have been seen at some of the carriers involved in mergers, as is discussed below.

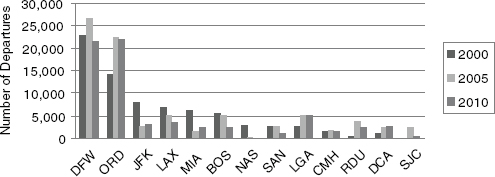

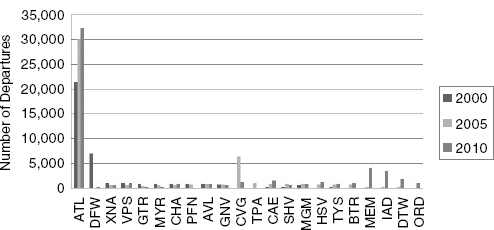

There is considerable variation in departure changes across the regional carriers. American Eagle, a regional carrier owned by American Airlines, has had a relatively stable pattern of service with its primary airports being the American hubs of Dallas and Chicago: see Figure 2-4. Similarly, Atlantic Southeast, which has been primarily a regional carrier affiliated with Delta, has focused much of its service on Atlanta: see Figure 2-5. When Delta stopped using Dallas and Cincinnati as hubs, Atlantic Southeast also saw

___________________

2A partial exception to this pattern was Frontier Airlines, which used a regional affiliate, Great Lakes Airlines, to provide some service, and it showed increases in departures over the period. Frontier, however, is something of a hybrid between a mainline and a regional airline in that it operates both larger Airbus aircraft (with more than 90 seats) and smaller regional jets with fewer than 90 seats.

FIGURE 2-3 Southwest departures by city.*

*In all figures for the airline departure analysis, cities are identified by the appropriate airport code. Provided in Appendix E is a list of airport codes alongside the corresponding airports and cities.

SOURCE: Data from Bureau of Transportation Statistics(n.d.-a).

FIGURE 2-4 American Eagle departures by city.

SOURCE: Data from Bureau of Transportation Statistics (n.d.-a).

declines in flights in those cities. Beginning in 2010, Atlantic Southeast has also been providing services associated with United Airlines.

In contrast, Air Wisconsin hts experienced greater change in its service patterns: see Figure 2-6. The two principal cities Air Wisconsin served in 2000 were Denver and Chicago, which it served as a United Express carrier. However, in 2010 it became a US Airways Express carrier and switched its primary cities from Denver and Chicago to the US Airways hubs of Philadelphia and Charlotte, both cities it had not served in 2000.

FIGURE 2-5 Atlantic Southeast departures by city.

SOURCE: Data from Bureau of Transportation Statistics (n.d.-a).

FIGURE 2-6 Air Wisconsin departures by city.

SOURCE: Data from Bureau of Transportation Statistics (n.d.-a).

Indeed, only one of the cities found in Air Wisconsin’s top 10 in 2000, Milwaukee, continued to receive Air Wisconsin service in 2010, and none of the cities that were top 10 Air Wisconsin cities in 2010 had been served by Air Wisconsin in 2000.

The Air Wisconsin experience illustrates how changes in contracts between the regional airlines and the mainline airlines can result in large changes in regional operations at specific hub airports, with associated changes in re-

gional pilot domicile assignment. Air Wisconsin effectively moved its entire operation to a different part of the country so that virtually all of its pilots experienced changes in their domiciles.

Mergers

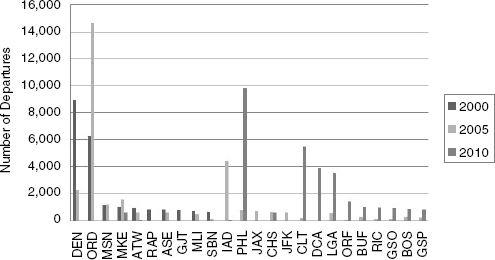

In addition to the rise of affiliated regional airlines, mergers also played an important role in the changing service patterns of the mainline airlines. For example, Delta and Northwest merged at the end of 2009. The merged Delta’s total departures are presented in Figure 2-7. Delta experienced steady declines in departures throughout the period.

Delta also experienced some sharp declines at some of their hubs, partly in the wake of the merger and partly for other reasons: see Figure 2-8. While the main Delta hub, Atlanta, experienced only small proportional declines in 2010, the former Northwest hubs of Detroit and Minneapolis/ St. Paul experienced sharper declines following the merger. However, not all the declines were necessarily related to the merger. Delta’s original Cincinnati hub experienced sharp declines before the merger and even sharper declines following the merger. The even sharper declines in aircraft departures at Dallas/Fort Worth indicate a decision made prior to the merger to no longer operate a hub at that airport. These sorts of sharp declines at airports that had once been hubs may well have placed pressure on pilots to alter their commuting patterns.

FIGURE 2-7 Delta total departures.

SOURCE: Data from Bureau of Transportation Statistics (n.d.-a).

FIGURE 2-8 Delta departures by city.

SOURCE: Data from Bureau of Transportation Statistics (n.d.-a).

After the merger was completed and the Delta and Northwest pilots had integrated their seniority lists, subsequent seniority-based bidding for domiciles and positions may have also resulted in changes to commuting patterns. For example, it is possible that some former Delta pilots who had homes in or near Minneapolis and had been commuting from Minneapolis to Atlanta could now bid to be domiciled at Minneapolis, a former Northwest hub, and have a shorter commute. Such opportunities, however, given the drop in departures in Minneapolis, may have been limited to pilots with relatively high seniority. Another possibility is that former Delta pilots who were both domiciled and living in Atlanta may have found their best post-merger opportunities were in a former Northwest hub and thus may have chosen a longer commute.

As can be seen both with the Delta/Northwest merger noted above and with the other merged carriers shown in Appendix E, mergers often result in decreases in departures at some of the premerger hubs as the merged airline consolidates its operations (as occurred for St. Louis following the American/TWA merger). But airlines have also sharply decreased departures at hubs for reasons not associated with mergers, as was seen in Delta’s reducing departures at Dallas/Fort Worth and in Appendix E with US Airways’ reducing departures at Pittsburgh. Regardless of the reason that hubs are sharply downsized or eliminated, such actions can put pressure on pilots either to relocate or to alter their commuting patterns. Flight departures are correlated with airline crew staffing requirements. Again, these hub airports are not synonymous with pilot domiciles, but the dynamic nature of hub departure volumes suggests that the staffing of pilots to operate the flights

passing through them has been subject to substantial change over at least the past decade. Lacking specific data about pilot commuting patterns, the committee was unable to measure the specific effects of mergers on pilot commuting.

In the absence of opportunities to commute by air, these changes in the airlines’ operating pattern could lead to large-scale, sometimes short-term, relocations of pilots and families or inflexibility in the airlines’ ability to adjust to changes in flight patterns and thus to staffing needs. Consequently, the availability of commuting by air allows airlines to adjust crew staffing and domiciles quickly in accordance with market demands.

AIRLINE POLICIES AND PRACTICES

Various airline policies and practices may facilitate or hinder pilots’ abilities to commute, particularly by air and over long distances. Such policies include access to free or reduced-rate air travel, commuting policies that spell out the consequences of failing to report to the domicile on time because of commuting, and policies related to sick leave (including attendance/reliability) and fatigue. For the most part, these policies are currently unregulated and subject to collective bargaining agreements. The committee requested information from airlines, airline associations, and pilot associations about these policies and practices. Responses were received from 33 airlines including mainline, regional, cargo, and charter carriers. It is important to note that these responses were a collection of heterogeneous submissions. Airlines provided a range of information: some airlines provided basic descriptive statements about their policies while others provided copies of the actual policies. The committee did not request nor receive information as to how these policies were developed, on what scientific research they were based, or on how the policies were implemented.

Access to Air Travel and Rest Facilities

As is the case with many other airline employees, pilots are able to take advantage of free or reduced-rate (nonrevenue) travel, on a standby basis. Nonrevenue travel is available on the pilot’s own airline network and, in many cases, also on other airlines. Seating may be available using unsold seats in the passenger cabin or the jumpseat, which is an additional observer seat on the flight deck available to other pilots by courtesy of the captain. Although some airlines allow pilots to reserve the flight deck jumpseat in advance, other carriers require pilots to stand by for the jumpseat until it is awarded to the senior requestor 30 minutes before flight time. Under these procedures, only the most senior pilots would be able to rely on obtaining a jumpseat for their commutes.

Some airlines have adopted additional corporate policies that facilitate pilot commuting by air or reduce the potential for stress and fatigue. For example, FedEx reported to the committee that it allowed pilots to reserve the jumpseat in advance; provided sleeping facilities at both its sorting hubs and outlying stations; and included the time spent in commuting from the pilot’s home airport to the domicile in the calculation of duty time with respect to the limits established by the labor contract. (Time spent commuting is not considered in duty time under current FAA regulations.) Similarly, Delta Airlines reported in a submission to the committee that it allows jumpseats to be reserved in advance. Some cargo and charter carriers that engage in home basing reported to the committee that they provided reserved seats for the trip to the pilot’s duty location and provided minimum rest periods of 4-9 hours, depending on the carrier, between the arrival of the commuting flight and commencement of preflight activities for a pilot’s operational flight.

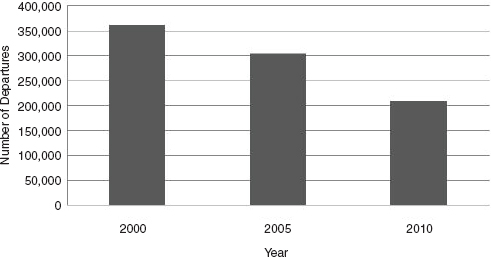

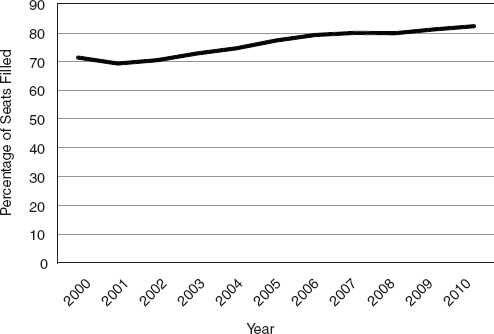

Although nonrevenue travel dramatically lowers the cost of commuting for pilots, it has the disadvantage of the uncertainty of standing by for open seats, especially given recently experienced record load factors.3Figure 2-9 shows the changes in system-wide domestic load factors from 2000 through 2010. By 2010, load factors had increased to over 82 percent. (Load factors on international flights by U.S. carriers were over 81 percent.) During the most popular travel times and on the most popular routes, load factors are even higher. The result is that there are fewer and fewer empty seats available to pilots (or other airline employees) for nonrevenue travel than was the case when load factors were lower.

Adding to uncertainty over commuting arrangements are flight delays and cancellations due to bad weather, air traffic control delays at congested hub airports, and flights delayed or cancelled because of unscheduled maintenance needs. Pilots told the committee in testimony that they experience stress from these uncertainties, with the risk of losing pay and being subject to disciplinary actions if their commute goes badly and they do not arrive at the domicile in a timely manner. Furthermore, they stated that the most common way to mitigate this uncertainty is to begin the commute on an earlier flight from the home airport to the domicile, which takes more time away from home and may reduce sleep opportunities prior to the start of duty.

Although some airlines provide quiet, dark, temperature-controlled sleeping facilities in or near the domicile, most airlines do not. Many pilots arrange for their own sleeping facilities at or near their domiciles. These facilities range from private apartments owned or rented by the pilots to

___________________

3The passenger load factor is a measure of how much of an airline’s passenger carrying capacity is used and is calculated as the ratio of revenue passenger miles to available seat miles.

FIGURE 2-9 U.S. carrier domestic load factors.

SOURCE: Data from Bureau of Transportation Statistics (n.d.-b).

hotel rooms rented by the night to temporary living arrangements shared among groups of pilots. The arrangements at shared accommodations (often referred to by pilots as “crash pads”) vary from a private bedroom regularly assigned and available to the pilot to a shared room with multiple bunk beds in which the pilot takes a “hot bunk” that is open for the night. Thus, shared accommodations can achieve the ideal of a quiet, dark, temperature-controlled sleeping area, or they can fall well short of the ideal. The quality of sleep obtainable at these locations, whether at hotels, shared apartments, or company provided rest facilities, may vary considerably.

The challenge of obtaining restful sleep in a less-than-ideal facility can further increase the stress of commuting and can contribute to pilots’ operating flights in a fatigued state. This outcome is more likely if a pilot commutes to the domicile with the intent of obtaining rest there, is unable to sleep well, anticipates becoming fatigued by the end of the upcoming duty shift, yet declines to call off the trip (desiring not to cause a flight delay or concerned about losing pay from a trip dropped due to fatigue).

Commuting Policies

A pilot who does not report to the domicile on time to prepare for the first operational flight of the trip (usually 1 hour prior to scheduled pushback) must be replaced by a reserve pilot. The flight’s departure may well be delayed if a late-arriving pilot does not alert the company about the situation ahead of time. Consequently, pilots who show up late for duty risk disciplinary actions up to and including termination. Airlines recognize that the uncertainties of commuting may be responsible for some late reports or no-shows for duty. It is in the interest of the airline to receive “prenotification” from pilots who are experiencing difficulty with their commute in order to facilitate the call-up of reserve pilots without the cost and disruption of a flight delay. However, it is also in the interest of the airline to maintain consequences for pilots who report late in order to motivate the pilots to arrive for duty reliably on time.

Consistent with these goals, some of the airlines that provided information to the committee reported the establishment of commuting policies that require pilots, for example, to attempt standby travel on two flights that have open seat availability and would arrive at the domicile on time. Pilots who do not clear the standby list for the first flight must then notify a crew scheduler or chief pilot about their situation (providing the airline with the desired advance notification of a possible late report). If these pilots do not clear standby for the second flight, they may be provided a reserved seat on the same flight (possibly bumping a paying passenger) or may be allowed to drop the beginning of their scheduled trip with loss of pay for the missed flight segments, depending on the airline’s policy. Under some commuting policies, pilots who provide the specified prenotification may be assured that no disciplinary action will be taken for the late arrival. At other airlines, disciplinary action may be taken for overuse or abuse of the commuting policy, while overuse or abuse may not be well defined. One airline reported to the committee that repeated use of the allowances in the commuting policy might result in the pilot losing the privileges of that policy in the future.

Sick Leave and Attendance/Reliability Policies

Regulations require the individual pilot to assess his or her fitness to fly and require pilots to decline to fly whenever unable to meet medical certification requirements (i.e., they are sick). Most airlines provide sick leave as an employee benefit, with an earned bank of sick or multipurpose leave hours for pilots to use to avoid loss of pay when missing a trip due to illness. Traditionally, 1 hour of the pilot’s earned sick leave bank would

be used to substitute for each hour of flying time on the missed trip (most pilots are paid by the hour of flight time, or more specifically, block time including taxiing).4

The potential relevance of sick leave to commuting, the committee was told informally, is that a pilot who is experiencing difficulty with a commute may choose to call in sick for the upcoming trip in order to maintain pay for the trip (which may be up to one-third of one’s monthly earnings, depending on the number of trips per month). Atlantic Southeast Airlines provided, in a submission to the committee, an excerpt from its Flight Operations Manual that “the use of sick leave when commute difficulties are encountered is a violation of Atlantic Southeast policy and could subject the pilot to discipline.” Regardless of stated policy, airlines recognize that this use or abuse of sick leave does occur. Perhaps in response (among other reasons), some airlines have established attendance and reliability policies that require pilots who frequently use sick leave to provide documentation of their illness and treatment, submit to interviews by flight managers, or be subject to disciplinary steps that may potentially lead to termination.

Fatigue Policies

Some airlines have established specific policies about flight crew fatigue. Uniformly, under the policies reported to the committee, airlines rely on the pilots to report fit for duty, including being properly rested, and also to notify the airline if they are too fatigued to operate safely at any time during a trip. In what appears to be a typical airline procedural response to a statement of fatigue by a pilot, Ameristar Air Cargo reported to the committee in a submission: “There are no adverse consequences for a pilot to call in fatigued. If a pilot uses the word ‘fatigue,’ ‘tired,’or similar wording that he or she is unfit for flight, that pilot is automatically removed from a flight assignment.” Beyond this initial response, there is variation as to whether, as a matter of policy or practice, managers interview or investigate pilots who make such fatigue calls. Reported policies varied as to whether the pilot receives pay for a trip not flown because of fatigue or forfeits the pay that would have been earned from the trip.

Delta Airlines reported to the committee that in its experience “… our recent reviews have not shown us a significant amount of absences or missed flights due to commuting. To our knowledge, we only have a few

___________________

4Under some labor agreements, though, the use of sick leave has been capped on a monthly basis, so a pilot calling in sick for a trip may lose some or all of the pay for that trip. This kind of agreement may provide a different incentive for a pilot who is sick to perhaps report for work and attempt to fly when not medically qualified.

fatigue situations per year that are associated with commuting.” However, no systemic, reliable information from any airline was available to the committee about the effects, if any, of commuting on pilots’ reliably arriving at their domicile on time for duty or about the effects, if any, of commuting on either fatigue or fatigue calls.