As described in Chapter 1, the steering committee grouped the five skills identified by previous efforts (National Research Council, 2008, 2010) into the broad clusters of cognitive skills, interpersonal skills, and intrapersonal skills. Based on this grouping, two of the identified skills fell within the cognitive cluster: nonroutine problem solving and systems thinking. The definition of each, as provided in the previous report (National Research Council, 2010, p. 3), appears below:

Nonroutine problem solving: A skilled problem solver uses expert thinking to examine a broad span of information, recognize patterns, and narrow the information to reach a diagnosis of the problem. Moving beyond diagnosis to a solution requires knowledge of how the information is linked conceptually and involves metacognition—the ability to reflect on whether a problem-solving strategy is working and to switch to another strategy if it is not working (Levy and Murnane, 2004). It includes creativity to generate new and innovative solutions, integrating seemingly unrelated information, and entertaining possibilities that others may miss (Houston, 2007).

Systems thinking: The ability to understand how an entire system works; how an action, change, or malfunction in one part of the system affects the rest of the system; adopting a “big picture” perspective on work (Houston, 2007). It includes judgment and decision making, systems analysis, and systems evaluation as well as abstract reasoning about how the different elements of a work process interact (Peterson et al., 1999).

After considering these definitions, the committee decided a third cognitive skill, critical thinking, was not fully represented. The committee added critical thinking to the list of cognitive skills, since competence in critical thinking is usually judged to be an important component of both skills (Mayer, 1990). Thus, this chapter focuses on assessments of three cognitive skills: problem solving, critical thinking, and systems thinking.

DEFINING THE CONSTRUCT

One of the first steps in developing an assessment is to define the construct and operationalize it in a way that supports the development of assessment tasks. Defining some of the constructs included within the scope of 21st century skills is significantly more challenging than defining more traditional constructs, such as reading comprehension or mathematics computational skills. One of the challenges is that the definitions tend to be both broad and general. To be useful for test development, the definition needs to be specific so that there can be a shared conception of the construct for use by those writing the assessment questions or preparing the assessment tasks.

This set of skills also generates debate about whether they are domain general or domain specific. A predominant view in the past has been that critical thinking and problem-solving skills are domain general: that is, that they can be learned without reference to any specific domain and, further, once they are learned, can be applied in any domain. More recently, psychologists and learning theorists have argued for a domain-specific conception of these skills, maintaining that when students think critically or solve problems, they do not do it in the absence of subject matter: instead, they think about or solve a problem in relation to some topic. Under a domain-specific conception, the learner may acquire these skills in one domain as he or she acquires expertise in that domain, but acquiring them in one domain does not necessarily mean the learner can apply them in another.

At the workshop, Nathan Kuncel, professor of psychology with University of Minnesota, and Eric Anderman, professor of educational psychology with Ohio State University, discussed these issues. The sections below summarize their presentations and include excerpts from their papers,1 dealing first with the domain-general and domain-specific con-

________________

1For Kuncel’s presentation, see http://www7.national-academies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Kuncel.pdf. For Kuncel’s paper, see http://www7.nationalacademies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Kuncel_Paper.pdf. For Anderman’s presentation, see http://www7.national-academies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Anderman.pdf. For Anderman’s paper, see http://nrc51/xpedio/groups/dbasse/documents/webpage/060387~1.pdf [August 2011].

ceptions of critical thinking and problem solving and then with the issue of transferring skills from one domain to another.

Critical Thinking: Domain-Specific or Domain-General

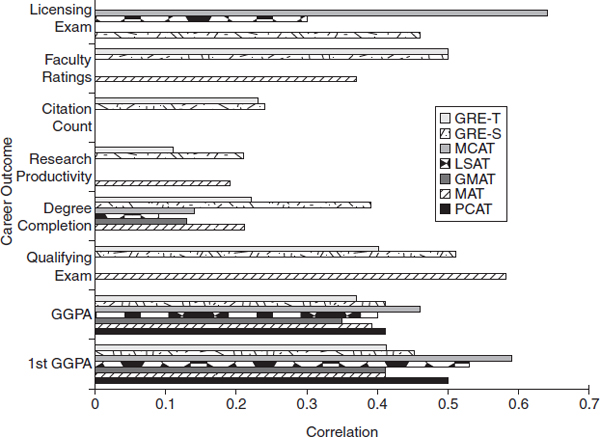

It is well established, Kuncel stated, that foundational cognitive skills in math, reading, and writing are of central importance and that students need to be as proficient as possible in these areas. Foundational cognitive abilities, such as verbal comprehension and reasoning, mathematical knowledge and skill, and writing skills, are clearly important for success in learning in college as well as in many aspects of life. A recent study documents this. Kuncel and Hezlett (2007) examined the body of research on the relationships between traditional measures of verbal and quantitative skills and a variety of outcomes. The measures of verbal and quantitative skills included scores on six standardized tests—the GRE, MCAT, LSAT, GMAT, MAT, and PCAT.2 The outcomes included performance in graduate school settings ranging from Ph.D. programs to law school, medical school, business school, and pharmacy programs. Figure 2-1 shows the correlations between scores on the standardized tests and the various outcome measures, including (from bottom to top) first-year graduate GPA (1st GGPA), cumulative graduate GPA (GGPA), qualifying or comprehensive examination scores, completion of the degree, estimate of research productivity, research citation counts, faculty ratings, and performance on the licensing exam for the profession. For instance, the top bar shows a correlation between performance on the MCAT and performance on the licensing exam for physicians of roughly .65, the highest of the correlations reported in this figure. The next bar indicates the correlation between performance on the LSAT and performance on the licensing exam for lawyers is roughly .35. Of the 34 correlations shown in the figure, all but 11 are over .30. Kuncel characterized this information as demonstrating that verbal and quantitative skills are important predictors of success based on a variety of outcome measures, including performance on standardized tests, whether or not people finish their degree program, how their performance is evaluated by faculty, and their contribution to the field.

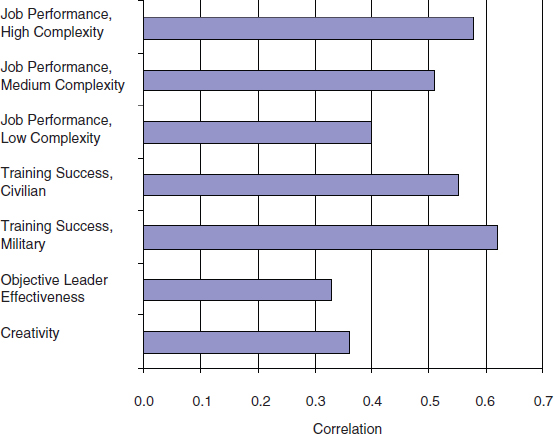

Kuncel has also studied the role that broader abilities have in predicting future outcomes. A more recent review (Kuncel and Hezlett, 2010) examined the body of research on the relationships between measures of general cognitive ability (historically referred to as IQ) and job outcomes,

________________

2Respectively, the Graduate Record Exam, Medical College Admission Test, Law School Admission Test, Graduate Management Admission Test, Miller Analogies Test, and Pharmacy College Admission Test.

FIGURE 2-1 Correlations between scores on standardized tests and academic and job outcome measures.

SOURCE: Kuncel and Hezlett (2007). Reprinted with permission of American Association for the Advancement of Science.

including performance in high, medium, and low complexity jobs; training success in civilian and military settings; how well leaders perform on objective measures; and evaluations of the creativity of people’s work. Figure 2-2 shows the correlations between performance on a measure of general cognitive ability and these outcomes. All of the correlations are above .30, which Kuncel characterized as demonstrating a strong relationship between general cognitive ability and job performance across a variety of performance measures. Together, Kuncel said, these two reviews present a body of evidence documenting that verbal and quantitative skills along with general cognitive ability are predictive of college and career performance.

Kuncel noted that other broader skills, such as critical thinking or analytical reasoning, may also be important predictors of performance, but he characterizes this evidence as inconclusive. In his view, the problems lie both with the conceptualization of the constructs as domain-general (as opposed to domain-specific) as well as with the specific definition of the construct. He finds the constructs are not well defined and have not

FIGURE 2-2 Correlations between measures of cognitive ability and job performance.

SOURCE: Kuncel and Hezlett (2011). Copyright 2010 by Sage Publications. Reprinted with permission of Sage Publications.

been properly validated. For instance, a domain-general concept of the construct of “critical thinking” is often indistinguishable from general cognitive ability or general reasoning and learning skills. To demonstrate, Kuncel presented three definitions of critical thinking that commonly appear in the literature:

- “[Critical thinking involves] cognitive skills or strategies that increase the probability of a desirable outcome—in the long run, critical thinkers will have more desirable outcomes than ‘noncritical’ thinkers…. Critical thinking is purposeful, reasoned, and goal-directed. It is the kind of thinking involved in solving problems, formulating inferences, calculating likelihoods, and making decisions” (Halpern, 1998, pp. 450-451).

- “Critical thinking is reflective and reasonable thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do” (Ennis, 1985, p. 45).

- “Critical thinking [is] the ability and willingness to test the validity of propositions” (Bangert-Drowns and Bankert, 1990, p. 3).

He characterizied these definitions both very general and very broad. For instance, Halpern’s definition essentially encompasses all of problem solving, judgment, and cognition, he said. Others are more specific and focus on a particular class of tasks (e.g., Bangert-Drowns and Bankert, 1990). He questioned the extent to which critical thinking so conceived is distinct from general cognitive ability (or general intelligence).

Kuncel conducted a review of the literature for empirical evidence of the validity of the construct of critical thinking. The studies in the review examined the relationships between various measures of critical thinking and measures of general intelligence and expert performance. He looked for two types of evidence—convergent validity evidence3 and discriminant validity4 evidence.

Kuncel found several analyses of the relationships among different measures of critical thinking (see Bondy et al., 2001; Facione, 1990; and Watson and Glaser, 1994). The assessments that were studied included the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (WGCTA), the Cornell Critical Thinking Test (CCTT), the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST), and the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI). The average correlation among the measures was .41. Considering that all of these tests purport to be measures of the same construct, Kuncel judged this correlation to be low. For comparison, he noted a correlation of .71 between two subtests of the SAT intended to measure critical thinking (the SAT-critical reading test and the SAT-writing test).

With regard to discriminant validity, Kuncel conducted a literature search that yielded 19 correlations between critical-thinking skills and traditional measures of cognitive abilities, such as the Miller Analogies Test and the SAT (Adams et al., 1999; Bauer and Liang, 2003; Bondy et al., 2001; Cano and Martinez, 1991; Edwards, 1950; Facione et al., 1995, 1998; Spector et al., 2000; Watson and Glaser, 1994). He separated the studies into those that measured critical-thinking skills and those that measured critical-thinking dispositions (i.e., interest and willingness to use one’s critical-thinking skills). The average correlation between gen-

________________

3Convergent validilty indicates the degree to which an operationalized construct is similar to other operationalized constructs that it theoretically should also be similar to. For instance, to show the convergent validity of a test of critical thinking, the scores on the test can be correlated with scores on other tests that are also designed to measure critical thinking. High correlations between the test scores would be evidence of convergent validity.

4Discriminant validity evaluates the extent to which a measure of an operationalized construct differs from measures of other operationalized constructs that it should differ from. In the present context, the interest is in verifying that critical thinking is a construct distinct from general intelligence and expert performance. Thus, discriminant validity would be examined by evaluating the patterns of correlations between and among scores on tests of critical thinking and scores on tests of the other two constructs (general intelligence and expert performance).

eral cognitive ability measures and critical-thinking skills was .48, and the average correlation between general cognitive ability measures and critical-thinking dispositions was .21.

Kuncel summarized these results as demonstrating that different measures of critical thinking show lower correlations with each other (i.e., average of .41) than they do with traditional measures of general cognitive ability (i.e., average of .48). Kuncel judges that these findings provide little support for critical thinking as a domain-general construct distinct from general cognitive ability. Given this relatively weak evidence of convergent and discriminant validity, Kuncel argued, it is important to determine if critical thinking is correlated differently than cognitive ability with important outcome variables like grades or job performance. That is, do measures of critical-thinking skills show incremental validity beyond the information provided by measures of general cognitive ability?

Kuncel looked at two outcome measures: grades in higher education and job performance. With regard to higher education, he examined data from 12 independent samples with 2,876 subjects (Behrens, 1996; Gadzella et al., 2002, 2004; Kowalski and Taylor, 2004; Taube, 1997; Williams, 2003). Across these studies, the average correlation between critical-thinking skills and grades was .27 and between critical-thinking dispositions and grades was .24. To put these correlations in context, the SAT has an average correlation with 1st year college GPA between .26 to .33 for the individual scales and .35 when the SAT scales are combined (Kobrin et al., 2008).5

There are very limited data that quantify the relationship between critical-thinking measures and subsequent job performance. Kuncel located three studies with the Watson-Glaser Appraisal (Facione and Facione, 1996, 1997; Giancarlo, 1996). They yielded an average correlation of .32 with supervisory ratings of job performance (N = 293).

Kuncel described these results as “mixed” but not supporting a conclusion that assessments of critical thinking are better predictors of college and job performance than other available measures. Taken together with the convergent and discriminant validity results, the evidence to support critical thinking as an independent construct distinct from general cognitive ability is weak.

Kuncel believes these correlational results do not tell the whole story, however. First, he noted, a number of artifactual issues may have contributed to the relatively low correlation among different assessments of critical thinking, such as low reliability of the measures themselves, restriction in range, different underlying definitions of critical thinking, overly broad

________________

5It is important to note that when corrected for restriction in range, these coefficients increase to .47 to .51 for individual scores and .51 for the combined score.

definitions that are operationalized in different ways, different kinds of assessment tasks, and different levels of motivation in test takers.

Second, he pointed out, even though two tests correlate highly with each other, they may not measure the same thing. That is, although the critical-thinking tests correlate .48, on average, with cognitive ability measures, it does not mean that they measure the same thing. For example, a recent study (Kuncel and Grossbach, 2007) showed that ACT and SAT scores are highly predictive of nursing knowledge. But, obviously, individuals who score highly on a college admissions test do not have all the knowledge needed to be a nurse. The constructs may be related but not overlap entirely.

Kuncel explained that one issue with these studies is they all conceived of critical thinking in its broadest sense and as a domain-general construct. He said this conception is not useful, and he summarized his meta-analysis findings as demonstrating little evidence that critical thinking exists as a domain-general construct distinct from general cognitive ability. He highlighted the fact that some may view critical thinking as a specific skill that, once learned, can be applied in many situations. For instance, many in his field of psychology mention the following as specific critical-thinking skills that students should acquire: understanding the law of large numbers, understanding what it means to affirm the consequent, being able to make judgments about sample bias, understanding control groups, and understanding Type I versus Type II errors. However, Kuncel said many tasks that require critical thinking would not make use of any of these skills.

In his view, the stronger argument is for critical thinking as a domain-specific construct that evolves as the person acquires domain-specific knowledge. For example, imagine teaching general critical-thinking skills that can be applied across all reasoning situations to students. Is it reasonable, he asked, to think a person can think critically about arguments for different national economic policies without understanding macroeconomics or even the current economic state of the country? At one extreme, he argued, it seems clear that people cannot think critically about topics for which they have no knowledge, and their reasoning skills are intimately tied to the knowledge domain. For instance, most people have no basis for making judgments about how to conduct or even prioritize different experiments for CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. Few people understand the topic of particle physics sufficiently to make more than trivial arguments or decisions. On the other hand, perhaps most people could try to make a good decision about which among a few medical treatments would best meet their needs.

Kuncel also talked about the kinds of statistical and methodological reasoning skills learned in different disciplines. For instance, chemists,

engineers, and physical scientists learn to use these types of skills in thinking about the laws of thermodynamics that deal with equilibrium, temperature, work, energy, and entropy. On the other hand, psychologists learn to use these skills in thinking about topics such as sample bias and self-selection in evaluating research findings. Psychologists who are adept at thinking critically in their own discipline would have difficulty thinking critically about problems in the hard sciences, unless they have specific subject matter knowledge in the discipline. Likewise, it is difficult to imagine that a scientist highly trained in chemistry could solve a complex problem in psychology without knowing some subject matter in psychology.

Kuncel said it is possible to train specific skills that aid in making good judgments in some situations, but the literature does not demonstrate that it is possible to train universally effective critical thinking skills. He noted, “I think you can give people a nice toolbox with all sorts of tools they can apply to a variety of tasks, problems, issues, decisions, citizenship questions, and learning those things will be very valuable, but I dissent on them being global and trainable as a global skill.”

Transfer from One Context to Another

There is a commonplace assumption, Eric Anderman noted in his presentation, that learners readily transfer the skills they have learned in one course or context to situations and problems that arise in another. Anderman argued research on human learning does not support this assumption. Research suggests such transfer seldom occurs naturally, particularly when learners need to transfer complex cognitive strategies from one domain to another (Salomon and Perkins, 1989). Transfer is only likely to occur when care is taken to facilitate that transfer: that is, when students are specifically taught strategies that facilitate the transfer of skills learned in one domain to another domain (Gick and Holyoak, 1983).

For example, Anderman explained, students in a mathematics class might be taught how to solve a problem involving the multiplication of percentages (e.g., 4.79% × 0.25%). The students then might encounter a problem in their social studies courses that involves calculating compounded interest (such as to solve a problem related to economics or banking). Although the same basic process of multiplying percentages might be necessary to solve both problems, it is unlikely that students will naturally, on their own, transfer the skills learned in the math class to the problem encountered in the social studies class.

In the past, Anderman said, there had been some notion that critical-thinking and problem-solving skills could be taught independent of context. For example, teaching students a complex language such as Latin,

a computer programming language such as LOGO, or other topics that require complex thinking might result in an overall increase in their ability to think critically and problem solve.

Both Kuncel and Anderman maintained that the research does not support this idea. Instead, the literature better supports a narrower definition in which critical thinking is considered a finite set of specific skills. These skills are useful for effective decision making for many, but by no means all, tasks or situations. Their utility is further curtailed by task-specific knowledge demands. That is, a decision maker often has to have specific knowledge to make more than trivial progress with a problem or decision.

Anderman highlighted four important messages emerging from recent research. First, research documents that it is critical that students learn basic skills (such as basic arithmetic skills like times tables) so the skills become automatic. Mastery of these skills is required for the successful learning of more complex cognitive skills. Second, the use of general practices intended to improve students’ thinking are not usually successful as a means of improving their overall cognitive abilities. The research suggests students may become more adept in the specific skill taught, but this does not transfer to an overall increase in cognitive ability. Third, when general problem-solving strategies are taught, they should be taught within meaningful contexts and not as simply rote algorithms to be memorized. Finally, educators need to actively teach students to transfer skills from one context to another by helping students to recognize that the solution to one type of problem may be useful in solving a problem with similar structural features (Mayer and Wittrock, 1996).

He noted that instructing students in general problem-solving skills can be useful but more elaborate scaffolding and domain-specific applications of these skills are often necessary. Whereas general problem-solving and critical-thinking strategies can be taught, research indicates these skills will not automatically or naturally transfer to other domains. Anderman stressed that educators and trainers must recognize that 21st century skills should be taught within specific domains; if they are taught as general skills, he cautioned, then extreme care must be taken to facilitate the transfer of these skills from one domain to another.

ASSESSMENT EXAMPLES

The workshop included examples of four different types of assessments of critical-thinking and problem-solving skills—one that will be used to make international comparisons of achievement, one used to license lawyers, and two used for formative purposes (i.e., intended to support instructional decision making). The first example was the com-

puterized problem-solving component of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). This assessment is still under development but is scheduled for operational administration in 2012.6 Joachim Funke, professor of cognitive, experimental, and theoretical psychology with the Heidelberg University in Germany, discussed this assessment.

The second example was the Multistate Bar Exam, a paper-and-pencil test that consists of both multiple-choice and extended-response components. This test is used to qualify law students for practice in the legal profession. Susan Case, director of testing with the National Conference of Bar Exams, made this presentation.

The two formative assessments both make use of intelligent tutors, with assessments embedded into instruction modules. The “Auto Tutor” described by Art Graesser, professor of psychology with the University of Memphis, is used in instructing high school and higher education students in critical thinking skills in science. The Auto Tutor is part of a system Graesser has developed called Operation ARIES! (Acquiring Research Investigative and Evaluative Skills). The “Packet Tracer,” described by John Beherns, director of networking academy learning systems development with Cisco, is intended for individuals learning computer networking skills.

Problem Solving on PISA

For the workshop, Joachim Funke supplied the committee with the draft framework for PISA (see Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 20107) and summarized this information in his presentation.8 The summary below is based on both documents.

PISA, Funke explained, defines problem solving as an individual’s capacity to engage in cognitive processing to understand and resolve problem situations where a solution is not immediately obvious. The definition includes the willingness to engage with such situations in order to achieve one’s potential as a constructive and reflective citizen (Organisation for Co-operation and Development, 2010, p. 12). Further, the PISA 2012 assessment of problem-solving competency will not test simple reproduction of domain-based knowledge, but will focus on the cognitive skills required to solve unfamiliar problems encountered in life and lying outside traditional curricular domains. While prior knowledge

________________

6For a full description of the PISA program, see http://www.oecd.org/pages/0,3417,en_32252351_32235731_1_1_1_1_1,00.html [August 2011].

7Available at http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/8/42/46962005.pdf [August 2011].

8Available at http://www7.national-academies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Funke.pdf [August 2011].

is important in solving problems, problem-solving competency involves the ability to acquire and use new knowledge or to use old knowledge in a new way to solve novel problems. The assessment is concerned with nonroutine problems, rather than routine ones (i.e., problems for which a previously learned solution procedure is clearly applicable). The problem solver must actively explore and understand the problem and either devise a new strategy or apply a strategy learned in a different context to work toward a solution. Assessment tasks center on everyday situations, with a wide range of contexts employed as a means of controlling for prior knowledge in general.

The key domain elements for PISA 2012 are as follows:

- The problem context: whether it involves a technological device

- or not, and whether the focus of the problem is personal or social

- The nature of the problem situation: whether it is interactive or

- static (defined below)

- The problem-solving processes: the cognitive processes involved in solving the problem

The PISA 2012 framework (pp. 18-19) defines four processes that are components of problem solving. The first involves information retrieval. This process requires the test taker to quickly explore a given system to find out how the relevant variables are related to each other. The test taker must explore the situation, interact with it, consider the limitations or obstacles, and demonstrate an understanding of the given information. The objective is for the test taker to develop a mental representation of each piece of information presented in the problem. In the PISA framework, this process is referred to as exploring and understanding.

The second process is model building, which requires the test taker to make connections between the given variables. To accomplish this, the examinee must sift through the information, select the information that is relevant, mentally organize it, and integrate it with relevant prior knowledge. This requires the test taker to represent the problem in some way and formulate hypotheses about the relevant factors and their interrelationships. In the PISA framework, this dimension is called representing and formulating.

The third process is called forecasting and requires the active control of a given system. The framework defines this process as setting goals, devising a strategy to carry them out, and executing the plan. In the PISA framework, this dimension is called planning and executing.

The fourth process is monitoring and reflecting. The framework defines this process as checking the goal at each stage, detecting unexpected events, taking remedial action if necessary, and reflecting on solu-

tions from different perspectives by critically evaluating assumptions and alternative solutions.

Each of these processes requires the use of reasoning skills, which the framework describes as follows (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2010, p. 19):

In understanding a problem situation, the problem solver may need to distinguish between facts and opinion, in formulating a solution, the problem solver may need to identify relationship between variables, in selecting a strategy, the problem solver may need to consider cause and effect, and in communicating the results, the problem solver may need to organize information in a logical manner. The reasoning skills associated with these processes are embedded within problem solving. They are important in the PISA context since they can be taught and modeled in classroom instruction (e.g., Adey et al., 2007; Klauer and Phye, 2008).

For any given test taker, the test lasts for 40 minutes. PISA is a survey-based assessment that uses a balanced rotation design. A total of 80 minutes of material is organized into four 20-minute clusters, with each student taking two clusters.

The items are grouped into units around a common stimulus that describes the problem. Reading and numeracy demands are kept to a minimum. The tasks all consist of authentic stimulus items, such as refueling a moped, playing on a handball team, mixing a perfume, feeding cats, mixing elements in a chemistry lab, taking care of a pet, and so on. Funke noted that the different contexts for the stimuli are important because test takers might be motivated differentially and might be differentially interested depending on the context. The difficulty of the items is manipulated by increasing the number of variables or the number of relations that the test taker has to deal with.

PISA 2012 is a computer-based test in which items are presented by computer and test takers respond on the computer. Approximately three-quarters of the items are in a format that the computer can score (simple or complex multiple-choice items). The remaining items are constructed-response, and test takers enter their responses into text boxes.

Scoring of the items is based on the processes that the test taker uses to solve the problem and involves awarding points for the use of certain processes. For information retrieval, the focus is on identifying the need to collect baseline data (referred to in PISA terminology as identifying the “zero round”) and the method of manipulating one variable at a time (referred to in PISA terminology as “varying one thing at a time” or VOTAT). Full credit is awarded if the subject uses VOTAT strategy and makes use of zero rounds. Partial credit is given if the subject uses VOTAT but does not make use of zero rounds.

For model building, full credit is awarded if the generated model is correct. If one or two errors are present in the model, partial credit is given. If more than two errors are present, then no credit is awarded.

For forecasting, full credit is given if the target goals are reached. Partial credit is given if some progress toward the target goals can be registered, and no credit is given if there is no progress toward target goals at all.

PISA items are classified as static versus interactive. In static problems, all the information the test taker needs to solve the problem is presented at the outset. In contrast, interactive problems require the test taker to explore the problem to uncover important relevant information (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2010, p. 15). Two sample PISA items appear in Box 2-1.

Funke and his colleagues have conducted analyses to evaluate the construct validity of the assessment. They have examined the internal structure of the assessment using structural equation modeling, which evaluates

BOX 2-1

Sample Problem-Solving Items for PISA 2012

Digital Watch–interactive:

A simulation of a digital watch is presented. The watch is controlled by four buttons, the functions of which are unknown to the student at the outset of the problems. The student is required to (Q1) determine through guided exploration how the buttons work in TIME mode, (Q2) complete a diagram showing how to cycle through the various modes, and (Q3) use this knowledge to control the watch (set the time).

Q1 is intended to measure exploring and understanding, Q2 measures representing and formulating, Q3 measures planning and executing.

Basketball–static

The rules for a basketball tournament relating to the way in which match time should be distributed between players are given. There are two more players than required (5) and each player must be on court for at least 25 of the 40 minutes playing time. Students are required to (Q1) create a schedule for team members that satisfies the tournament rules, and (Q2) reflect on the rules by critiquing an existing schedule.

Q1 is designed to measure planning and executing, Q2 measures monitoring and reflecting.

SOURCE: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2010, p. 28). Reprinted with permission of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

the extent to which the items measure the dimensions they are intended to measure. The results indicate the three dimensions are correlated with each other. Model Building and Forecasting correlate at .77; Forecasting and Information Retrieval correlate at .71; and Information Retrieval and Model Building correlate at .75. Funke said that the results also document that the items “load on” the three dimensions in the way the test developers hypothesized. He indicated some misfit related to the items that measure Forecasting, and he attributes this to the fact that the Forecasting items have a skewed distribution. However, the fit of the model does not change when these items are removed.

Funke reported results from studies of the relationship between test performance and other variables, including school achievement and two measures of problem solving on the PISA German National Extension on Complex Problem Solving. The latter assessment, called HEIFI, measures knowledge about a system and the control of the system separately. Scores on the PISA Model Building dimension are statistically significant (p < .05) related to school achievement (r = .64) and to scores on the HEIFI knowledge component (r = .48). Forecasting is statistically significant (p < .05) related to both of the HEIFI scores (r = .48 for HEIFI knowledge and r = .36 for HEIFI control). Information Retrieval is statistically significant (p < .05) related to HEIFI control (r = .38). The studies also show that HEIFI scores are not related to school achievement.

Funke closed by discussing the costs associated with the assessment. He noted it is not easy to specify the costs because in a German university setting, many costs are absorbed by the department and its equipment. Funke estimates that development costs run about $13 per unit,9 plus $6.5 for the Cognitive Labs used to pilot test and refine the items.10 The license for the Computer Based Assessment (CBA) Item-builder and the execution environment is given for free for scientific use from DIPF11 Frankfurt.

The Bar Examination for Lawyers12

The Bar examination is administered by each jurisdiction in the United States as one step in the process to license lawyers. The National Council of Bar Examiners (NCBE) develops a series of three exams for use by the jurisdictions. Jurisdictions may use any or all of these three

________________

9A unit consists of stimulus materials, instructions, and the associated questions.

10Costs are in American dollars.

11DIPF stands for the Deutsches Institut für Internationale Pädagogische Forschung, which translates to the German Institute for Educational Research and Educational Information.

12The summary is based on a presentation by Susan Case, see http://www7.nationalacademies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Case.pdf [August 2011].

exams or may administer locally developed exam components if they wish. The three major components developed by the NCBE include the Multi-state Bar Exam (MBE), the Multi-state Essay Exam (MEE), and the Multi-state Performance Test (MPT). All are paper-and-pencil tests. Examinees pay to take the test, and the costs are $54 for the MBE, $20 for the MEE, and $20 for the MPT.

Susan Case, who has spent her career working on licensing exams—first the medical licensing exam for physicians and then the bar exam for lawyers—noted the Bar examination is like other tests used to award professional licensure. The focus of the test is on the extent to which the test taker has the knowledge and skills necessary to be licensed in the profession on the day of the test. The test is intended to ensure the newly licensed professional knows what he/she needs to know to practice law. The test is not designed to measure the curriculum taught in law schools, but what licensed professionals need to know. When they receive the credential, lawyers are licensed to practice in all fields of law. This is analogous to medical licensing in which the licensed professional is eligible to practice any kind of medicine.

The Bar exam includes both multiple-choice and constructed-response components. Both require examinees to be able to gather and synthesize information and apply their knowledge to the given situation. The questions generally follow a vignette that describes a case or problem and asks the examinee to determine the issues to resolve before advising the client or to determine other information needed in order to proceed. For instance, what questions should be asked next? What is the best strategy to implement? What is the best defense? What is the biggest obstacle to relief? The questions may require the examinee to synthesize the law and the facts to predict outcomes. For instance, is the ordinance constitutional? Should a conviction be overturned?

The MBE

The purpose of the MBE is to assess the extent to which an examinee can apply fundamental legal principles and legal reasoning to analyze a given pattern of facts. The questions focus on the understanding of legal principles rather than memorization of local case or statutory law. The MBE consists of 60 multiple-choice questions and lasts a full day.

A sample question follows:

A woman was told by her neighbor that he planned to build a new fence on his land near the property line between their properties. The woman said that, although she had little money, she would contribute something toward the cost. The neighbor spent $2,000 in materials and a day of his time to construct the fence. The neighbor now wants her to pay half the cost of the materials. Is she liable for this amount?

The MEE

The purpose of the MEE is to assess the examinee’s ability to (1) identify legal issues raised by a hypothetical factual situation; (2) separate material that is relevant from that which is not; (3) present a reasoned analysis of the relevant issues in a clear, concise, and well-organized composition; and (4) demonstrate an understanding of the fundamental legal principles relevant to the probable resolution of the issues raised by the factual situation.

The MEE lasts for 6 hours and consists of nine 30-minute questions. An excerpt from a sample question follows:

The CEO/chairman of the 12-member board of directors (the Board) of a company plus three other members of the Board are senior officers of the company. The remaining eight members of the Board are wholly independent directors.

Recently, the Board decided to hire a consulting firm to market a new product …

The CEO disclosed to the Board that he had a 25% partnership interest in the consulting firm. The CEO stated that he would not be involved in any work to be performed by the consulting firm. He knew but did not disclose to the Board that the consulting firm’s proposed fee for this consulting assignment was substantially higher than it normally charged for comparable work …

The Board discussed the relative merits of the two proposals for 10 minutes. The Board then voted unanimously (CEO abstaining) to hire the consulting firm …

1. Did the CEO violate his duty of loyalty to his company? Explain.

2. Assuming the CEO breached his duty of loyalty to his company, does he have any defense to liability? Explain.

3. Did the other directors violate their duty of care? Explain.

The MPT

The purpose of the MPT is to assess fundamental lawyering skills in realistic situations by asking the candidate to complete a task that a beginning lawyer should be able to accomplish. The MPT requires applicants to sort detailed factual materials; separate relevant from irrelevant facts; analyze statutory, case, and administrative materials for relevant principles of law; apply relevant law to the facts in a manner likely to resolve a client’s problem; identify and resolve ethical dilemmas; communicate effectively in writing; and complete a lawyering task within time constraints.

Each task is completely self-contained and includes a file, a library, and a task to complete. The task might deal with a car accident, for

example, and therefore might include a file with pictures of the accident scene and depositions from the various witnesses, as well as a library with relevant case law. Examinees are given 90 minutes to complete each task.

For example, in a case involving a slip and fall in a store, the task might be to prepare an initial draft of an early dispute resolution for a judge. The draft should candidly discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the client’s case. The file would contain the instructional memo from the supervising attorney, the local rule, the complaint, an investigator’s report, and excerpts of the depositions of the plaintiff and a store employee. The library would include a jury instruction concerning the premises liability with commentary on contributory negligence.

Scoring

The MBE is a multiple-choice test and thus scored by machine. However, the other two components require human scoring. The NCBE produces the questions and the grading guidelines for the MEE and MPT, but the essays and performance tests are scored by the jurisdictions themselves. The scorers are typically lawyers who are trained during grading seminars held at the NCBE offices, after the exam is administered. At this time, they review sample papers and receive training on how to apply the scoring guidelines in a consistent fashion.

Each component of the Bar examination (MBE, MEE, MPT) is intended to assess different skills. The MBE focuses on breadth of knowledge, the MEE focuses on depth of knowledge, and the MPT focuses on the ability to demonstrate practical skills. Together, the three formats cover the different types of tasks that a new lawyer needs to do.

Determinations about weighting the three components are left to the jurisdictions; however, the NCBE urges them to weight the MBE score by 50 percent and the MEE and MPT by 25 percent each. The recommendation is an attempt to balance a number of concerns, including authenticity, psychometric considerations, logistical issues, and economic concerns. The recommendation is to award the highest weight to the MBE because it is the most psychometrically sound. The reliability of scores on the MBE is generally over .90, much higher than scores on the other portions, and the MBE is scaled and equated across time. The recommended weighting helps to ensure high decision consistency and comparability of pass/fail decisions across administrations.

Currently the MBE is used by all but three jurisdictions (Louisiana, Washington, and Puerto Rico). The essay exam is used by 27 jurisdictions, and the performance test is used by 34 jurisdictions.

Test Development

Standing test development committees that include practicing lawyers, judges, and lawyers on staff with law schools write the test questions. The questions are reviewed by outside experts, pretested on appropriate populations, analyzed and revised, and professionally edited before operational use. Case said the test development procedures for the Bar exam are analogous to those used for the medical licensure exams.

Operation ARIES! (Acquiring Research

Investigative and Evaluative Skills)

The summary below is based on materials provided by Art Graesser, including his presentation13 and two background papers he supplied to the committee (Graesser et al., 2010; Millis et al., in press).

Operation ARIES! is a tutorial system with a formative assessment component intended for high school and higher education students, Graesser explained. It is designed to teach and assess critical thinking about science. The program operates in a game environment intended to be engaging to students. The system includes an “Auto Tutor,” which makes use of animated characters that converse with students. The Auto Tutor is able to hold conversations with students in natural language, interpret the student’s response, and respond in a way that is adaptive to the student’s response. The designers have created a science fiction setting in which the game and exercises operate. In the game, alien creatures called “Fuaths” are disguised as humans. The Fuaths disseminate bad science through various media outlets in an attempt to confuse humans about the appropriate use of the scientific method. The goal for the student is to become a “special agent of the Federal Bureau of Science (FBS), an agency with a mission to identify the Fuaths and save the planet” (Graesser et al., 2010, p. 328).

The system addresses scientific inquiry skills, developing research ideas, independent and dependent variables, experimental control, the sample, experimenter bias, and relation of data to theory. The focus is on use of these skills in the domains of biology, chemistry, and psychology. The system helps students to learn to evaluate evidence intended to support claims. Some examples of the kinds of research questions/claims that are evaluated include the following:

________________

13For Graesser’s presentation, see http://nrc51/xpedio/groups/dbasse/documents/webpage/060267~1.pdf [August 2011].

From Biology:

- Do chemical and organic pesticides have different effects on food quality?

- Does milk consumption increase bone density?

From Chemistry:

- Does a new product for winter roads prevent water from freezing?

- Does eating fish increase blood mercury levels?

From Psychology:

- Does using cell phones hurt driving?

- Is a new cure for autism effective?

The system includes items in real-life formats, such as articles, advertisements, blogs, and letters to the editor, and makes use of different types of media where it is common to see faulty claims.

Through the system, the student encounters a story told by video, combined with communications received by e-mail, text message, and updates. The student is engaged through the Auto Tutor, which involves a “tutor agent” that serves as a narrator, and a “student agent” that serves in different roles, depending on the skill level of the student.

The system makes use of three kinds of modules—interactive training, case studies, and interrogations. The interactive training exchanges begin with the student reading an e-book, which provides the requisite information used in later modules. After each chapter, the student responds to a set of multiple-choice questions intended to assess the targeted skills. The text is interactive in that it involves “trialogs” (three-way conversations) between the primary agent, the student agent, and the actual (human) student. It is adaptive in that the strategy used is geared to the student’s performance. If the student is doing poorly, the two auto-tutor agents carry on a conversation that promotes vicarious learning: that is, the tutor agent and the student agent interact with each other, and the human student observes. If the student is performing at an intermediate level, normal tutoring occurs in which the student carries on a conversational exchange with the tutor agent. If the student is doing very well, he or she may be asked to teach the student agent, under the notion that the act of teaching can help to perfect one’s skills.

In the case study modules, the student is expected to apply what he or she has learned. The case study modules involve some type of flawed science, and the student is to identify the flaws by applying information learned from the interactive text in the first module. The student responds by verbally articulating the flaws, and the system makes use of advances in computational linguistics to analyze the meaning of the response. The researchers adopted the case study approach because it “allows learners to encode and discover the rich source of constraints and interdependen-

cies underlying the target elements (flaws) within the cases. [Prior] cases provide a knowledge base for assessing new cases and help guide reasoning, problem solving, interpretation and other cognitive processes” (Millis et al., in press, p. 17).

In the interrogation modules, insufficient information is provided, so students must ask questions. Research is presented in an abbreviated fashion, such as through headlines, advertisements, or abstracts. The student is expected to identify the relevant questions to ask and to learn to discriminate good research from flawed research. The storyline is advanced by e-mails, dialogues, and videos that are interspersed among the learning activities.

Through the three kinds of modules, the system interweaves a variety of key principles of learning that Graesser said have been shown to increase learning. These include

- Self-explanation (where the learner explains the material to another student, such as the automated student)

- Immediate feedback (through the tutoring system)

- Multimedia effects (which tend to engage the student)

- Active learning (in which students actually participate in solving a problem)

- Dialog interactivity (in which students learn by engaging in conversations and tutorial dialogs)

- Multiple, real-life examples (intended to help students transfer what they learn in one context to another context and to real world situations)

Graesser closed by saying that he and his colleagues are beginning to collect data from evaluation studies to examine the effects of the Auto Tutor. Research has focused on estimating changes in achievement before and after use of the system, and, to date, the results are promising.

Packet Tracer

The summary below is based on materials provided by John Behrens, including his presentation14 and a background paper he forwarded in preparation for the workshop (Behrens et al., in press).

To help countries around the world train their populations in networking skills, Cisco created the Networking Academy. The academy is a public/private partnership through which Cisco provides free online

________________

14For Behrens’ presentation, see http://www7.national-academies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Behrens.pdf [August 2011].

curricula and assessments. Behrens pointed out that in order to become adept with networking, students need both a conceptual understanding of networking and the skills to apply this knowledge to real situations. Thus, hands-on practice and assessment on real equipment are important components of the academy’s instructional program. Cisco also wants to provide students with time for out-of-class practice and opportunities to explore on their own using online equipment that is not typically available in the average classroom setting. In the Networking Academy, students work with an online instructor, and they proceed through an established curriculum that incorporates numerous interactive activities.

Behrens talked specifically about a new program Cisco has developed called “Packet Tracer,” a computer package that uses simulations to provide instruction and includes an interactive and adaptable assessment component. Cisco has incorporated Packet Tracer activities into the curricula for training networking professionals. Through this program, instructors and students can construct their own activities, and students can explore problems on their own. In Cisco’s Networking Academy, assessments can be student-initiated or instructor-initiated. Student-initiated assessments are primarily embedded in the curriculum and include quizzes, interactive activities, and “challenge labs,” which are a feature of Packet Tracer. The student-initiated assessments are designed to provide feedback to the student to help his or her learning. They use a variety of technologies ranging from multiple-choice questions (in the quizzes) to complex simulations (in the challenge labs). Before the development of Packet Tracer, the instructor-initiated assessments consisted either of hands-on exams with real networking equipment or multiple-choice exams in the online assessment system. Packet Tracer provides more simulation-based options, and also includes detailed reporting and grade-book integration features.

Each assessment consists of one extensive network configuration or troubleshooting activity that may require up to 90 minutes to complete. Access to the assessment is associated with a particular curricular unit, and it may be re-accessed repeatedly based on instructor authorization. The system provides simulations of a broad range of networking devices and networking protocols, including features set around the Cisco IOS (Internet Operating System). Instructions for tasks can be presented through HTML-formatted text boxes that can be preauthored, stored, and made accessible by the instructor at the appropriate time.

Behrens presented an example of a simulated networking problem in which the student needs to obtain the appropriate cable. To complete this task, the student must determine what kind of cable is needed, where on the computer to plug it in, and how to connect it. The student’s performance is scored, and his or her interactions with the problem are

tracked in a log. The goal is not to simply assign a score to the student’s performance but to provide detailed feedback to enhance learning and to correct any misinterpretations. The instructors can receive and view the log in order to evaluate how well the student understands the tasks and what needs to be done.

Packet Tracer can simulate a broad range of devices and networking protocols, including a wide range of PC facilities covering communication cards, power functionality, web browsers, and operating system configurations. The particular devices, configurations, and problem states are determined by the author of the task (e.g., the instructor) in order to address whatever proficiencies the chapter, course, or instruction targets. When icons of the devices are touched in the simulator, more detailed pictures are presented with which the student can interact. The task author can program scoring rules into the system. Students can be observed trying and discarding potential solutions based on feedback from the game resulting in new understandings. The game encourages students to engage in problem-solving steps (such as problem identification, solution generation, and solution testing). Common incorrect strategies can be seen across recordings.