TASKS RELATED TO COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS RESEARCH

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Cognitive Rehabilitation Therapy (CRT) for Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) was asked to determine if there is sufficient evidence to support widespread use of CRT interventions in the Military Health System (MHS), including TRICARE coverage. In the Statement of Task, the committee was charged with assessing the literature not only for efficacy but also for effectiveness (“the committee will consider comparison groups such as … other non-pharmacological treatment”) as well as any evidence of harm or safety issues. Thus, subtasks 1 through 3 of the Statement of Task to the committee include requests for analysis of any existing literature that directly compares alternative treatment approaches. Such an analysis directly falls within the definition of comparative effectiveness research (IOM 2009).

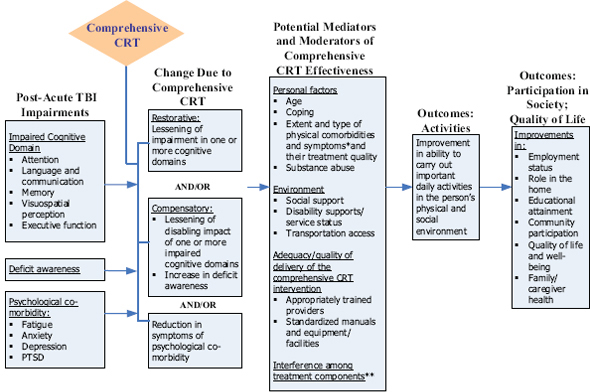

A primary tenet of comparative effectiveness research is to evaluate which preventions and treatments work for which patients. This tenet reflects “the growing potential for individualized and predictive medicine— based on advances in genomics, systems biology, and other biomedical sciences—through the analysis of subgroups with demographic, ethnic, physiologic, and genetic characteristics that could be useful factors in clinical decisions” (IOM 2009). CRT interventions are multi-faceted, and by definition, tailored to the particular individual. Interventions intend to address not only specific domains of cognitive impairment, but also potential mediators and moderators of a CRT intervention’s effect (Figure A-1). These mediators or moderators may include characteristics unique to the

FIGURE A-1 Model for multi-modal/comprehensive CRT.

* For example: visual impairment, headache, dizziness.

** For example: side effect of medication for depression interferes with attention.

individual, the type and extent of comorbidities, or the type and one or more cognitive deficits. Furthermore, the unique characteristics of the individual may reflect preexisting conditions or factors unrelated to TBI, such as presence of a sleep disturbance or extent of family support to enhance participation in or reinforcement of the intervention.

TASKS RELATED TO IMPLEMENTATION RESEARCH

The committee was also asked to assess adequacy of the “training, education, and experience” of providers of CRT, which falls within the scope of implementation research. Such research aims to analyze whether clinical interventions with evidence of efficacy are being delivered in real-world, nonexperimental settings by usual providers, and if so, whether the interventions continue to have a net health benefit. Thus, implementation research not only observes levels of care and barriers to provision of high-quality care, but also designs and evaluates policy or health care delivery system interventions that may improve the uptake or delivery of a clinical therapy. In that way, the health benefit of a therapy—across a population— is maximally achieved in the context of its value. This issue is particularly relevant to CRT, since such interventions are more complex than delivery of a drug and require

1. Availability of specific protocols and tools for delivering a particular CRT intervention,

2. Adequately trained CRT providers, and

3. A context that maximizes sufficient participation by the patient to achieve the benefit of the CRT.

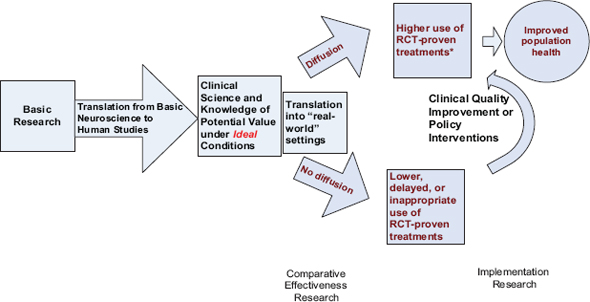

TRANSLATING EVIDENCE INTO PRACTICE THROUGH PHASED IMPLEMENTATION AND EVALUATION

The IOM Clinical Research Roundtable developed a now widely accepted conceptual model of the research stages (Sung et al. 2003). As depicted in Figure A-2, research stages include discovery of disease mechanisms in the laboratory, development of efficacious therapeutics, and translation of evidence-based therapies into widespread practice. To translate evidence-based therapies to care generally calls for a phased series of studies, due to the need to reengineer or redesign the way care is usually delivered. These kinds of behavior or organizational changes are often complex, and initial implementation approaches require extensive investigator involvement in design and oversight of the change process. Strategies that are successful in more tightly controlled environments must become broadly disseminated in heterogeneous care settings, with less investigator involvement.

FIGURE A-2 Clinical research continuum.

SOURCE: Vickrey et al. (submitted).

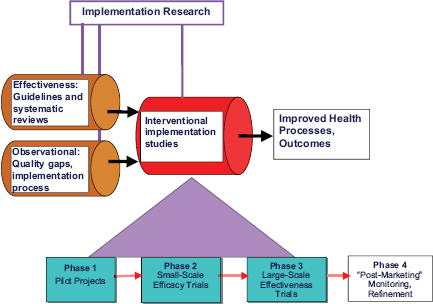

Furthermore, change strategies apply evaluations later in the process, focusing on a qualitative analysis of how and how well the intervention is implemented, and whether the intervention continues to have beneficial impact (Figure A-3) (Stetler et al. 2008). These kinds of evaluations are particularly relevant for nonpharmacological interventions like CRT. For an example beyond TBI literature, interventions to facilitate behavioral or lifestyle changes in diet and physical activity for hypertension control utilize these evaluations (Appel et al. 2003).

CRT FOR TBI AND COMORBIDITIES COMMON IN THE MILITARY SETTING

The literature reviewed for this report illustrates that TBI occurring in a military context is commonly accompanied by comorbidities, including symptoms of psychological distress and possible co-occurring diagnoses of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or anxiety disorder. Physical comorbidities also may exist, including pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, visual impairment, or effects of polytrauma from blast injuries. The recognition and management of these comorbidities will impact end-indicator outcomes such as health-related quality of life or employment;

FIGURE A-3 Refined research-implementation pipeline.

SOURCE: Adapted from Stetler et al. 2008.

these outcomes are also targeted by rehabilitation directed toward specific or multiple cognitive domains. The recently funded Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) SCORE! trial began enrollment in 2011. The study addresses pervasive TBI comorbidities through inclusion of a comparator arm in which both cognitive and psychological comorbidities are systematically screened for and addressed in a strategy tailored to the individual. This clinically pragmatic approach recognizes that multiple, applicable, efficacious clinical interventions should be tailored to the problems of the individual, both the primary cognitive domain(s) affected and any comorbidities. This approach is analogous to those developed and tested for certain chronic conditions that have a broad range of symptom manifestations.

For example, Alzheimer’s disease not only affects memory but also is often accompanied by a wide and varied range of behavior problems and depression in the patient; safety issues; as well as depression, anxiety, and stress in family caregivers. To successfully delay declines in patient health outcomes and to improve caregiver outcomes requires screening for problems, prioritizing goals with the patient and the caregiver, and implementing and following up on care management protocols likely to maximize benefit for that patient–caregiver dyad (Vickrey et al. 2006). In general, U.S. health care is moving toward care delivery strategies for chronic diseases that are preventive; ongoing; include structured, systematic assessments; engage the patient in self-management; and utilize health information technology (IT) to make care delivery more efficient (Wagner et al. 1996). This trend is in contrast to the traditional model of doctor visit–based care, which is more reactive to problems and arose from an era in which acute therapy for problems such as infections and injuries was the standard.

Evidence for the efficacy of CRT for specific domains of cognitive impairment can guide clinical decision making and coverage decisions for individuals with deficits in those domains with similar contexts and clinical profiles as participants in those trials. Yet most individuals with blast-related TBI have other comorbidities not studied in civilian trials. Several studies that research multi-faceted interventions to address multiple comorbidities and broader affected populations are under way (see Appendix C). The findings from these trials will need to be incorporated into future coverage and clinical service decisions to inform subsequent research studies that aim to build on those findings.

RESOURCES FOR COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS RESEARCH APPLICABLE TO ONGOING RESEARCH ON CRT FOR TBI

Prospectively planned analyses of clinically rich data sets are increasingly used to monitor and evaluate the implementation and impact of

clinical and policy interventions in health care. These analyses enable researchers to reassess effectiveness—including both benefits and harms—of interventions as they move into routine care from controlled settings and populations where they have been tested for efficacy. Types of research approaches used for comparative effectiveness and implementation research include systematic reviews, randomized trials, modeling, and observational studies. Observational studies are potentially less expensive to perform than randomized trials. However, observational studies require sufficient clinical variables to enable meaningful analyses, considering disease severity and factors that would influence choice of treatment and outcomes. Likewise, analyses to compare outcomes of different treatment approaches should account for these factors.

The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, a private, nonprofit organization established in 2011, includes a Methodology Committee charged with identifying areas of research to improve the quality of findings from comparative effectiveness studies, particularly observational study designs. An evolving resource that will make observational studies of comparative effectiveness more useful and feasible to conduct is the growth of longitudinal patient registries. Such registries go beyond administrative claims data, which typically lack sufficient clinical data on disease severity. Larger, integrated health care delivery systems are creating registries that link administrative claims data with pharmacy data, laboratory data, electronic medical records, and increasingly, patient-reported data collected in a systematic fashion, to minimize missing data on key variables (Paxton et al. 2010). In the case of CRT in the MHS, a registry could be used to analyze implementation of CRT and the associated outcomes. Such a registry would need to prospectively collect additional data elements, including operationally defined categories or a taxonomy of CRT treatments, as well as the ability to assess (i.e., through analysis of a sample of cases) the extent to which care consistent with CRT is currently delivered by physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, or other providers. Doing so allows for capture of current patterns and any changes over time via new or modified policy or expanded, evidence-based practices.

The growth in technological capacity for electronic medical records and the national investment in health IT capability are fueling the opportunity to build registries with clinical utility, with few downsides. A registry resource would ideally allow for ongoing investigations of the effectiveness of CRT delivery and coverage policies in the MHS and TRICARE by enabling researchers to access deidentified data (with appropriate approvals) and other resources. This access would help researchers ensure data or a subset of clinically enriched data are prospectively captured and updated. This type of investment will ensure the timely and efficient conduct of

1. Future research on effectiveness and implementation of alternative CRT approaches for members of the military and veterans,

2. Analyses to be used by health care administrators to make decisions about the personnel and resources currently in place and needed in the future to broadly implement CRT interventions identified as of value for certain populations, and

3. Policy analyses on health and cost consequences of existing CRT coverage policies, which will guide future recommendations for changes in coverage for these clinical services as the evidence base and the affected population change over time.

There are many strategies for establishing a registry. Ideally, specific data elements on the delivery of CRT would be built into new or recently created registries and observational studies sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), including the congressionally mandated 15-year longitudinal study of TBI outcomes in soldiers being carried out by DVBIC.

POTENTIAL OPPORTUNITIES

Opportunities for advancing knowledge of what works for CRT in TBI and for efficiently translating that knowledge into health care delivery systems and maximizing health outcomes include the following:

• In currently planned DoD and VA registries, purposefully embed the necessary data elements about types of CRT and providers, to prospectively analyze current care patterns and costs, and factors associated with variation (Gliklich and Dreyer 2010).

• Prospectively plan to evaluate current care and any changes in response to policy decisions or new evidence, analogous to the VAs QUERI program and REACH program (Gitlin et al. 2010; Nichols et al. 2011). Outcomes to be assessed in such an evaluation are impact on utilization, benefits, harms, families, and unmet need, as well as quality of care delivered relative to current or usual care patterns.

• Account for heterogeneity of populations and forthcoming advances in disease mechanisms and markers by designing studies of CRT interventions or programs for TBI to include subgroup-level results, as done with comparative effectiveness research on different modes of health care delivery (Kent et al. 2010). This can be accomplished by ongoing surveillance for new evidence, particularly on subgroup effectiveness (Shekelle et al. 2009).

• Create a publicly accessible database of the interventions, including tools (manual, protocols, other resources) for delivering them,

facilitating implementation of new evidence about CRT. This would also enable qualitative analysis of what components appear common to effective interventions, analogous to the Rosalynn Carter Caregiving Institute database of effective caregiver interventions.

REFERENCES

Appel, L. J., C. M. Champagne, D. W. Harsha, L. S. Cooper, E. Obarzanek, P. J. Elmer, V. J. Stevens, W. M. Vollmer, P. H. Lin, L. P. Svetkey, S. W. Stedman, and D. R. Young. 2003. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: Main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 289(16):2083–2093.

Gitlin, L. N., M. Jacobs, and T. V. Earland. 2010. Translation of a dementia caregiver intervention for delivery in homecare as a reimbursable Medicare service: Outcomes and lessons learned. The Gerontologist 50(6):847–854.

Gliklich, R. E., and N. A. Dreyer, eds. 2010. Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide. 2nd edition. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kent, D. M., P. M. Rothwell, J. P. Ioannidis, D. G. Altman, and R. A. Hayward. 2010. Assessing and reporting heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials: A proposal. Trials 11:85.

Nichols, L. O., J. Martindale-Adams, R. Burns, M. J. Graney, and J. Zuber. 2011. Translation of a dementia caregiver support program in a health care system—REACH VA. Archives of Internal Medicine 171(4):353–359.

Paxton, E. W., M. Inacio, T. Slipchenko, and D. C. Fithian. 2010. The Kaiser Permanente National Total Joint Replacement Registry. The Permanente Journal 12(3):12–16.

Shekelle, P., S. Newberry, M. Maglione, R. Shanman, B. Johnsen, J. Carter, A. Motala, B. Hulley, Z. Wang, D. Bravata, M. Chen, and J. Grossman. 2009. Assessment of the need to update comparative effectiveness reviews: Report of an initial rapid program assessment (2005–2009). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK49457/pdf/TOC.pdf (accessed July 12, 2011).

Stetler, C. B., B. S. Mittman, and J. Francis. 2008. Overview of the VA quality enhancement research initiative (QUERI) and QUERI theme articles: QUERI series. Implementation Science 3:8.

Sung, N. S., W. F. Crowley, M. Genel, P. Salber, L. Sandy, L. M. Sherwood, S. B. Johnson, V. Catanese, H. Tilson, K. Getz, E. L. Larson, D. Scheinberg, E. A. Reece, H. Slavkin, A. Dobs, J. Grebb, R. A. Martinez, A. Korn, and D. Rimoin. 2003. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. Journal of the American Medical Association 289(10):1278–1287.

Vickrey, B. G., B. S. Mittman, K. I. Connor, M. L. Pearson, R. D. Della Penna, T. G. Ganiats, R. W. Demonte, Jr., J. Chodosh, X. Cui, S. Vassar, N. Duan, and M. Lee. 2006. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 145(10):713–726.

Vickrey, B. G, D. Hirtz, S. Waddy, E. M. Cheng, and S. C. Johnston. (submitted). Comparative effectiveness and implementation research: Directions for neurology.

Wagner, E. H., B. T. Austin, and M. Von Korff. 1996. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank Quarterly 74(4):511–544.

This page intentionally left blank.