Climate Change Education Goals and

Outcomes for Various Public Audiences

The second workshop session built on the earlier discussion of the goals for climate change education (see Chapter 1) to explore effective strategies for engaging with various target audiences. The session was framed around audience segmentation strategies that are becoming increasingly common to climate change discussions, such as addressing people’s receptivity to information about climate change or their capacity to comprehend various messages around climate change based on their underlying mental models. In this session, experts examined the nature of understanding and engagement with climate change across diverse audiences and the cultural and political factors that influence them. They also considered whether particular goals are more appropriate—or more likely to be realized—for different target audiences and discussed where various target audiences currently obtain climate change information.

Moderator Charles “Andy” Anderson (Michigan State University) introduced the session, emphasizing that it would explore how to identify and communicate effectively with different types of audiences.

DIVERSE AUDIENCES FOR CLIMATE CHANGE EDUCATION

Anthony Leiserowitz (Yale University) introduced a series of research studies that examined how different segments of the American public respond to climate change information and the important role that emotion, imagery, associations, and values have in shaping those responses (Leiserowitz, Moser, and Dilling, 2007). His presentation focused pri-

marily on his most recent study, which investigated knowledge about climate change gained through learning in both formal and informal science education environments (Leiserowitz and Smith, 2010). The study, which is ongoing, is based on interviews conducted with a representative sample of 2,030 adults ages 18 and older between June 25 and July 22, 2010. According to some preliminary results that Leiserowitz described, knowledge about climate change can be divided into several general and overlapping categories:

• knowledge about how the climate system works;

• specific knowledge about the causes, consequences, and potential solutions to global warming;

• contextual knowledge placing human-caused global warming in historical and geographic perspective; and

• practical knowledge that enables individual and collective action.

The study included a series of questions asking respondents to rate their level of knowledge in terms of each of these dimensions. Other questions addressed the respondents’ desire for more information, trust in different information sources, perceptions of the risks of climate change, policy preferences, and behaviors.

In previous research, Leiserowitz (Maibach, Roser-Renouf, and Leiserowitz, 2009) identified six unique segments of the American public, referred to as Global Warming’s Six Americas, each of which responds to information about climate change in distinct ways. The Six Americas represent a broad spectrum of responses to climate change, from active engagement to complete dismissal. They are categorized as follows:

1. The “Alarmed” represent the most engaged public; they believe that global warming is occurring, that it is human-caused, and that it is a serious threat.

2. The “Concerned” believe that global warming is a serious but distant threat and are less personally engaged with the issue.

3. The “Cautious” are less certain that global warming is happening or that it is human induced and do not have a sense of urgency about it.

4. The “Disengaged” don’t know or think about the issue.

5. The “Doubtful” are split between believing and disbelieving in global warming, but those who accept global warming are most likely to believe that it is due to natural causes and does not pose a threat to people.

6. The “Dismissive” are actively engaged with the issue but do not believe global warming is happening, represents a threat, or warrants a national response.

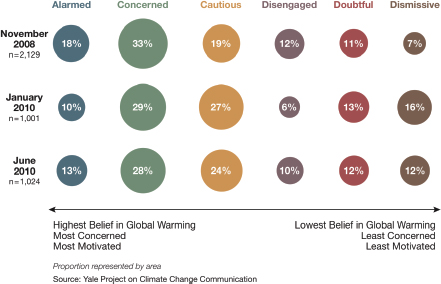

Leiserowitz noted that his nationally representative surveys from fall 2008 to January 2010 show a significant decrease in the group identified as “Alarmed,” coupled with a significant increase in the percentage of respondents who could be classified as “Dismissive” (see Figure 2-1). He noted that this research complements other national polls that seem to indicate that the public’s acceptance of climate change and its human causes has decreased (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 2007), which he attributed to several causes including the economy and high unemployment, the concurrent major decline in media coverage, two snowy winters on the east coast, an active and effectual denial industry, and the “climategate scandal.”

Leiserowitz highlighted several survey questions in his current research that ask about respondents’ belief in global warming and its relationship to human actions, noting that the responses show stark differences among the Six Americas segments. The percentage of respondents who expressed belief in climate change and its human causes declined steadily across the groups, from the Alarmed to the lowest level among the Dismissive. In response to the question of whether respondents are worried about global warming, there was a large drop in the percentage expressing a great deal of worry, from 71 percent of the Alarmed to only 18 percent of the Concerned. Leiserowitz noted that many people who are

FIGURE 2-1 Changes in opinions about climate change by audience segmentation.

SOURCE: Leiserowitz et al. (2010).

not part of the Alarmed, but do accept global warming as a scientific fact, see it as a problem distant in time and space.

Commenting on results from a line of questioning that explored whether people understood the greenhouse effect and global warming’s relationship to the earth’s protective ozone layer, Leiserowitz observed that many people believe that climate change and the ozone hole are the same problem, or that the ozone hole is the cause of global warming, and therefore come to the wrong conclusions about the appropriate solutions. He also pointed to the fact that more accurate knowledge about climate science may not trump other fundamental beliefs or agendas that stand in competition to addressing climate change.

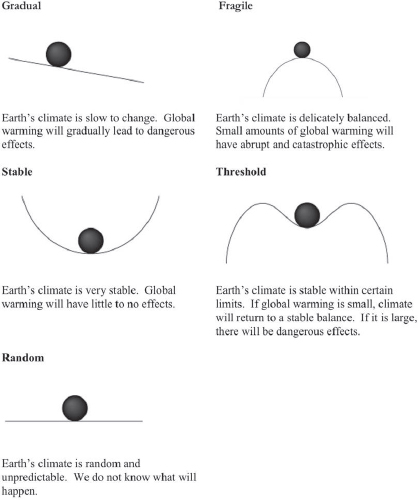

In an attempt to gauge individuals’ deeper understanding of the climate system, Leiserowitz’ study participants were asked to select one of several alternative conceptual models of climate change. The models were composed of five figures representing the climate system as (1) a gradual, incremental process; (2) a fragile system easily pushed to catastrophic events; (3) a stable system able to keep itself in balance; (4) a system that would remain in balance within certain thresholds but would become a new system if pushed beyond; and (5) a completely random and unpredictable system (see Figure 2-2). Almost half of the Dismissives picked the stable model, suggesting that, even if they could be convinced that global warming is occurring and is caused by greenhouse gases, they believe that these changes would not affect the climate system much. These respondents view human activities as too insignificant to affect the global climate system. One positive note from the study was that most respondents (except those in the Doubtful and Dismissive groups) indicated that they were not well informed about climate change and demonstrated overwhelming support for more education, including a national education effort targeting children.

Leiserowitz explained that this study also examined the types of information needed to reach different audiences. He noted that the Dismissive and Doubtful most frequently sought answers to such questions as “How do you know that global warming is occurring?” and “Why should I trust the messenger?” and that demographically these respondents tended to be white men. Overall, however, the variations in responses were more strongly associated with personal perceptions about what individuals “knew” and felt to be true than with gender, race, or other demographic factors.

Leiserowitz concluded that there are important gaps in the public’s knowledge of climate change and how to respond to it, including widespread misconceptions about climate change and the earth as a system. These misconceptions lead some people to doubt that global warming is occurring or that human activities are a major contributor; misunder-

FIGURE 2-2 Conceptual models used to gauge understanding of climate change.

SOURCE: Leiserowitz and Smith (2010).

standing the causes of climate change and therefore the solutions as well as the risks. Reiterating that the Six Americas groups respond to climate change information in very different ways, he emphasized that people actively interpret information and construct their own mental models based on what they personally know, value, and feel. Leiserowitz ended by saying that knowledge is necessary but insufficient to meet the needs of different audience segments.1

____________

1More information on this research is available at http://environment.yale.edu/climate.

AUDIENCE SEGMENTATION, MENTAL MODELS, AND

TARGETING CLIMATE CHANGE EDUCATION

Ann Bostrom (University of Washington) focused on three topics: audience segmentation, mental models and decision making, and the issue of targeting messages to different audience segments. She began by drawing on some of her previous research (Reynolds et al., 2010) to compare Leiserowitz’s work on the Six Americas with her own research on audience segmentation. Although she referred to the group he calls Dismissives as “discounters” and to his Alarmed as “enthusiasts,” the groups demonstrate similar characteristics. The enthusiasts/Alarmed tend to believe in everything that represents environmental good practice and accept any information that explains climate change or supports ways to combat it. The Disengaged tend to say they don’t know or care about this information. And the discounters/Dismissives tend to be well informed on questions of climate science but don’t believe in the basic scientific content or that climate change is influenced by human activity; consequently, they do not see any need for taking action.

Bostrom then turned to the importance of mental models—representations of reality people construct to explain phenomena and that are congruent to varying degrees with representations of reality favored by scientific research. She cited a study (see Bostrom et al., 1994; Read et al., 1994; Reynolds et al., 2010) demonstrating the tendency of enthusiasts/alarmists to adopt what she described as an environmental good practice model. Based on this mental model, group members tend to think that anything considered environmentally “bad” is contributing to climate change, from toxic chemicals in the air to stratospheric ozone depletion. She observed that the enthusiasts’ belief in the effectiveness of a climate change mitigation strategy was related to whether they viewed the strategy as an environmentally good practice in general. She stated that these findings reinforce the research conclusions of Leiserowitz that these types of beliefs can lead enthusiasts/alarmists to support climate change mitigation policies that are ineffective or nonspecific. Bostrom emphasized that climate change communicators and educators need to think carefully about this problem when working with enthusiasts/alarmists. Drawing on the background paper by Nisbet (2010), she observed that providing information to correct this group’s misconceptions could be an effective strategy but cautioned that the information must be rooted in the appropriate context. In addition, she stressed that false current beliefs or misconceptions can only be addressed with effective and appropriate alternative conceptions, mental models that resonate with the learner and that address the issue in a scientifically acceptable way.

Bostrom ended by addressing targeting, asking whether it is more effective to target a message based on understanding of individuals’

mental models and beliefs about climate change, or to target opportunities for reaching specific audiences, that is, information channels that people already use and trust. She referred to a recent study of risk analysis (unpublished data), noting that some people have already had personal experiences of climate change. For example, gardeners have noticed the earlier onset of spring, and Montana residents have experienced more wildfires. Although these individuals may consist primarily of enthusiasts, they have the ability to serve as opinion leaders and help to educate their communities about climate change.

BELIEFS ABOUT CLIMATE SCIENCE AND

CONCERN ABOUT GLOBAL WARMING

Aaron McCright (Michigan State University) introduced his current research on public understanding of climate change, explaining that it follows from previous research on the subject (McCright, 2010). Noting that his findings reinforce Leiserowitz’s research on the Six Americas, he said that his research indicates that “the strongest predictors of climate change acceptance and concern can be loosely characterized as environmental values, environmental identity, belonging to environmental groups, and having pro-ecological values versus anthropocentric values.” The second and third strongest predictors are political ideology and party identification.

Analyzing Gallup Poll data from 2001 to 2010, McCright addressed two related questions: (1) what social, political, and economic variables relate to individuals’ beliefs and attitudes about climate change and (2) what are the social, political, and economic characteristics of climate change deniers (McCright, 2010). The answers to these questions, he said, increase understanding of patterns and trends in the American public’s opinions on climate change. Identifying the characteristics of individuals more likely to accept or deny the reality and seriousness of climate change may allow leaders of public education efforts to more effectively frame their messages to key audience segments and/or identify barriers to existing education efforts.

McCright found a sizable political divide between liberals/Democrats and conservatives/Republicans on the issue of global warming, with liberals and Democrats more likely to hold beliefs consistent with the scientific consensus and to express concern about this environmental problem than conservatives and Republicans. Noting that this divide has grown substantially over the past decade, he argued that flows of political messages and news about global warming are likely to be contributors to the divide. People’s political orientations moderate the relationship between level of educational attainment and level of belief in climate

change and between level of educational attainment and level of concern about climate change. He cited a study by Hindman (2009) that argues that individuals with different ideologies or political affiliations are likely to receive very different or even conflicting information on global warming—in ways that reinforce their existing political differences.

McCright argued that his findings about the influence of political orientation challenge the common assumption of climate change educators that more information will help convince people of the need to respond to climate change. Simply providing more information seems particularly unlikely to prove effective for reaching the large segment of the public on the right of the political spectrum—especially if the information is provided through established scientific communication channels. He emphasized that public opinion about global warming is significantly polarized. Observing that ideological and political elites have become increasingly polarized on a wide range of issues in recent decades—including environmental issues, such as climate change—McCright said that the public has followed this trend of political polarization. Even if this polarization trend slows or reverses, the political divide in the American public will remain much larger than it was in 2001—the year that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change clearly established the current scientific consensus on climate change (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2001).

In closing, McCright turned to research focused on conservative white males (CWMs) and the characteristics of climate deniers. He noted that research findings provided strong evidence that conservative white males are more likely than other adults to espouse climate change denial (McCright, 2010). Furthermore, CWMs who report that they understand global warming very well—a group he referred to as “confident” CWMs—express the greatest degree of denial. Even controlling for this denialism, McCright found that Republicans, more religious individuals, and those unsympathetic to the environmental movement are more likely to report denialist beliefs than their respective counterparts.

Like several speakers before him, McCright also concluded by cautioning that these research findings pose a challenge to the deficit model of public education campaigns, which try to simply get more information out. He noted that a careful analysis of the different factors associated with climate change denial can help illuminate the importance of trust in sources of information on controversial topics.

SOCIAL CONTEXT FOR CLIMATE CHANGE EDUCATION

Psychologist Susan Clayton (College of Wooster) opened her talk by emphasizing that education is a social interaction in which those who give

a message and those who receive it play social roles and are influenced by the surrounding context. Although education is typically thought of as a process of increasing knowledge by transmitting an informational message, the acceptance of a message involves emotional and behavioral components as well as cognitive ones. The strong emotional responses evoked by climate change are an inextricable part of the way in which people evaluate information about the phenomenon. In an age of information overload, social context helps an individual decide whether to pay attention to a message, encourages the individual to continue to think about a message after the delivery, and provides an interpretive framework for making sense of information.

Clayton stressed that the social context can create negative emotional responses to a message about climate change, which may include fear, shame, guilt, or anxiety. Although some emotional response is useful in attracting attention or avoiding complacency, too much fear or anxiety can make people shut down in denial. Moreover, if a message makes people feel that their lifestyles are being personally attacked, they are likely to respond defensively by trying to discredit the message and its source. However, a message may also generate positive emotional responses, as people may feel proud of what they or their social groups are doing to address climate change and working together may enhance feelings of connectedness to one’s community.

Clayton said her research indicates that the emotional response to a climate change message will also affect the behavioral response. In her view, climate change education will be effective only if it convinces people to change their behavior, such as modifying unsustainable lifestyles or advocating for policies to address the problem. She observed that many people do not act because of uncertainty about the best course of action or a feeling that they are incapable of effective action. Clayton proposed that education should train people in the behaviors and skills most effective in addressing climate change. In the best case, this type of climate change education would enhance perceptions of self-efficacy, motivate people to learn more, and, as a result, become even more effective in their actions.

Information about what others are doing is also both informative and motivational, according to Clayton. Conformity is a very powerful force, she said, and substantial research is showing that some people will behave in ways that are completely inconsistent with their own beliefs and values in order to follow social norms. To motivate individuals to act, education efforts might include not only factual information, but also concrete examples of the ways in which specific individuals are working to address climate change.

In closing, Clayton argued that the context in which a climate change message is received is an important factor that can foster the educational

mission. The context is particularly influential in informal education, but it can also be important in formal settings. An educational message that fosters social interaction can attract individuals’ attention, promote their retention of the message, and encourage them to engage with the message. Social interactions around climate change education may strengthen social capital and the bonds between individuals in a group. In some cases, such interactions may encourage people to feel a stronger sense of community and social connection. For example, such connections developed in six small Kansas communities that joined a climate and energy project and greatly reduced their energy use, despite residents’ skepticism about global warming. The project focused on “thrift, patriotism, spiritual conviction, and economic prosperity” to encourage residents to conserve energy; the program resulted in up to 5 percent decline in energy use within these communities in comparison to other areas (Kaufman, 2010). The success of this project, Clayton said, reinforced her earlier point that people who may deny or reject climate change can be reached by talking about topics they relate to and consider part of their social identity.

MAPPING GOALS AND OUTCOMES TO

PARTICULAR AUDIENCES:

PANEL DISCUSSION

Session moderator Anderson facilitated a discussion among the presenters and the audience. As an entry point, he asked each member of the panel to answer the question of whether different goals are appropriate or more likely to be realized with different audiences.

Leiserowitz responded that, given the broad challenge of climate change and the diversity of the American public, there is not a one-size-fits-all approach to climate change education. Individuals take on many different roles that potentially influence or are influenced by climate change, acting at different times as energy users, consumers, members of a political party or religious organization, and citizens. He argued that the goals of various education initiatives focusing on these different roles are completely different, suggesting that educators need to carefully develop their messages to align with the desired goals or outcomes.

McCright stated that most people do not consider their political preferences to be a master identity, because other roles and values—such as their identity as parents or their position in the workplace—are more important. He explained that, when communicating about behavioral change rather than simply transmitting information, it is possible to approach individuals in ways that do not provoke the political divide. He expressed concern about messages that reinforce political divisions

around climate change, as the different groups may become increasingly unwilling to communicate.

Elaborating on Leiserowitz’s earlier suggestion that education strategies focus on goals, Clayton observed that, since climate change education has many different goals, a single education effort cannot attempt to achieve every one of them simultaneously. She identified several possible goals, such as enlightening the public, creating behavior change, or invoking a sense of community and responsibility, emphasizing that a particular educational message can be matched to a particular goal. She agreed with McCright that people do not have a single identity and may best be reached through messages tailored to their different roles.

Audience Comments and Questions

Thomas Bowman (Bowman Design Group) asked the panelists how important it is to improve climate literacy as a step toward developing new cultural values that would lead Americans to respond effectively to climate change. Clayton responded that climate literacy is important if the goal is a long-term increase in public understanding and development of solutions, but it may not be the most important factor if the goal is short-term behavior change. In either case, a population that understands basic climate science and can interpret scientific information will help to advance all of the various goals of climate change education. Bostrom added that an exciting aspect of the National Research Council’s Roundtable on Climate Change Education, which generated the idea for the workshop, is its integration of both formal and informal education. Noting that the current generation of students receives almost no formal education in climate change, she said that integrating informal and formal learning may be the best way to increase climate literacy.

Roundtable chair James Mahoney asked whether the panelists’ observations extended to decision makers who deal with climate change in their work. Leiserowitz responded that climate change educators need to be able to provide the level of sophisticated information required by professionals, emphasizing that educators should help to prepare a workforce of experts, researchers, and communicators trained to solve current and evolving climate change challenges. Clayton explained that the workplace provides a social context in which people may more readily receive climate change information, and McCright encouraged the climate education community to draw on the research on the sociology of organizations and organizational change.

David Hassenzahl asked if the research findings on the segmentation of different audiences within the American public helps to identify points of entry, in which climate change education is likely to garner the greatest

effects. Leiserowitz responded that, although climate change has become the latest issue in the broader debate over environmental protection, it represents a much larger and more fundamental challenge to the nation. He argued that it is very important for the climate change education community “to break out of the environment box, and the political box, to avoid being mired down in the ongoing cultural wars.” Leiserowitz observed that climate change can be legitimately and accurately characterized as a public health issue, an economic competitiveness issue, a national security issue, and a moral and a religious issue. He advocated framing messages in these contexts, to help all audience segments recognize that their values are at stake in climate change.

David Blockstein (National Council for Science and the Environment) noted that two types of goals for climate change education had emerged in the discussions: a knowledge goal and a behavioral influencing goal. He asked whether the panelists had been able to distinguish the extent to which people’s belief in the reality of climate change is generated by their attention to scientific findings rather than attention to behavioral changes. Leiserowitz responded with his finding that the Dismissives who belong to the group most likely to disbelieve in climate change are driven, not by scientific findings, but by the threat of a policy solution that violates their values. He noted that a Yale study targeting climate change skeptics found that, when skeptics were told directly that climate change was a serious problem that required action, they responded overwhelmingly with disbelief (Leiserowitz and Smith, 2010). However, if they were told that nuclear power was the best way to solve climate change, skeptics were more likely to accept that climate change is occurring and poses a threat.

Bostrom agreed with Leiserowitz that the framing of questions influences the extent of public support for climate change mitigation policies. She mentioned a study showing that, when people were directly asked to support carbon taxes, they responded negatively, but when asked to support programs that offset the costs of emissions, they responded positively2 (Hardisty, Johnson, and Weber, 2010). McCright added that the direct effects of political ideology or party identification on preferences for alternative policies to reduce carbon dioxide emissions are very small or nonexistent. Overall, 75-80 percent of the public favors a range of policies to address climate change, but there may not be the political will to move forward.

Jill Karsten (National Science Foundation) asked whether studies of audience segmentation—similar to the Six Americas study—had been used to develop successful strategies for climate change education.

____________

2Also supported by data recently collected and analyzed by Daniel Read, currently unpublished.

Leiserowitz responded that he is analyzing responses to climate change—related questions included in the Gallup World Poll, with data from more than 150 countries. His research group has found huge differences across countries and world regions; for example, climate change is not an issue in Latin America and South America, and, globally, 4 out of 10 people have never heard of climate change. He described this lack of awareness of climate change as “an education challenge.”

Clayton added that the relationship between one’s belief or disbelief in climate change and one’s political views is very different in different countries. For example, in China, where the government strongly supports taking action to address climate change, one cannot be pro-government and deny climate change, as in the United States. Leiserowitz added that the United Kingdom’s approach to climate change provides an interesting counterpoint to the United States. Although the right side of the political spectrum in the United States has made denial of climate change part of their election strategy, Prime Minister David Cameron’s Conservative Party was elected (in coalition with the Liberal Democrats) in 2010 on a platform that “absolutely accepted climate change.” Leiserowitz suggested that this demonstrates that a conservative ideology need not prevent accepting and responding to climate change.

BREAKOUT GROUP DISCUSSIONS

During the breakout sessions, the carousel brainstorming technique was again used to facilitate discussion. To initiate the conversation, the steering committee provided the following guiding questions:

1. Based on the goals identified in Session 1 and considering the research on audiences, what are the most important climate change education goals for each audience?

2. What factors and barriers must be addressed to realize the indicated goals for audiences (e.g., values, incorrect mental models and preconceptions, receptivity, misconceptions)?

3. Should certain audiences be higher priority than others? Which ones? Why?

During the breakout sessions, participants revisited the goals of climate change education that had emerged in the earlier session and grouped them into several major categories, noting that reaching each set of goals will require intervening steps. One major category includes knowledge and action goals. In this category, participants discussed the idea that climate change educators could focus first on the learning (knowledge) goals, followed by skill development to increase the audi-

ence’s capacity for action. Participants noted that, although knowledge is essential, skills are necessary to translate knowledge into behavioral changes. People in several groups emphasized the need to speak with members of the various audiences to establish the right set of goals for that particular audience, and they cautioned against focusing on the need to simply fill a person’s knowledge and skill deficits. Rather, they said, educators need to focus on what experience and information they can share that would have value to that audience.

Most of the breakout groups expressed the view that audience segmentation is useful in prioritizing strategies for communicating about climate change, but they had different perspectives on the usefulness of considering the Six Americas study specifically. One group thought the study findings were impractical; other groups viewed them more favorably. However, participants in every group expressed the need for prioritization of audiences and messages in order to make best use of available resources.

People in several groups thought that the most strategic way to prioritize audiences is to determine whether a particular audience can influence others. They identified several audiences as high priority, based on this capacity for influence, including formal educators, informal educators (e.g., weather forecasters), and decision makers. Bostrom’s earlier comments about the need to be practical when prioritizing target audiences resonated with a number of participants.

Several groups focused on priorities in terms of the audiences identified in the Six Americas study. They described the alarmed group as a natural audience for climate change educators. However, at least one participant was distressed by the serious misunderstandings in this group, which climate change educators have reached most successfully. People responded that educators can help the alarmed group to develop a better understanding of the science to solidify their support for real solutions, to show this group how to take actions that will truly have a positive impact on climate change problems, and to activate the group as educators for peers in their social environment.

Several groups also described the concerned audience as important because its members already lean toward accepting and understanding climate change issues. Participants discussed the idea of connecting with the concerned group by framing climate change as a concrete issue with real-world effects. For example, educators could emphasize the local or regional effects of climate change. Other participants noted that focusing on local impacts might also be helpful to reach the discounters/Dismissives and the doubtfuls. Various groups reflected on the successful program in Kansas described by Clayton (Kaufman, 2010). Participants noted that, by responding to community needs and respecting local

opinions and values, the program helped people find their own reasons to reduce their use of fossil fuels.

In the discussions, three fairly distinct categories of barriers to understanding the science of climate change, accepting the need to act to mitigate climate change, and actual behavior that would effectively address the issue were identified: (1) personal-level barriers, such as the mental models described by Bostrom; (2) social-level barriers, which can be viewed as people’s normative interactions with one another and reinforcement for one another’s actions; and (3) institutional or structural-level barriers, which enable action or prevent it from occurring. Some people thought that the climate change education community would be wise to target the decision makers who influence civic and private infrastructure, from public transportation to the energy efficiency of consumer products, and thereby determine the range of options available to consumers and private citizens. And others said that climate change educators could target local, regional, and national opinion leaders in politics, media, art, civic society, and business who can shape the cultural and political discussions on climate change and, in part, determine shared cultural values that provide the social context in which individuals navigate their own identities.

This page intentionally left blank.