Implications of Audience Research and

Segmentation for Education Strategies

During the third session of the workshop, discussions centered on practical approaches to educating both the public and decision makers about climate change. A panel of six leaders in climate change education described effective and ineffective education strategies and explored how to scale up the most effective strategies. Representing practitioner and scholarly perspectives, the panelists’ discussion set the stage for the afternoon breakout sessions, which provided an opportunity for participants to delve into the strategies more deeply.

To launch the discussion, moderator David Blockstein (National Council for Science and the Environment) asked each panelist to provide an example of a climate change education activity that was successful in reaching the public and to comment on why it was successful.

CLIMATE CHANGE EDUCATION FOR SPECIFIC AUDIENCES

Sportsmen and Other Interest Groups

Kevin Coyle (National Wildlife Federation) described the approach developed by the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) to engage leaders in influential communities as voices for both personal and civic actions on climate and broader policy reforms (Coyle, 2010). From 2007 to 2010, the NWF trained 5,000 leaders in climate education from selected constituent groups. The training programs were developed based on lessons learned in an initial effort focused on hunters and anglers.

Coyle noted that 35 million people in the United States are part of the hunter and angler community. Many live in rural areas, have fairly conservative political views, and belong to the National Rifle Association. About 50 percent declare themselves to be evangelicals, and approximately 80 percent voted Republican in the last two presidential elections. This community’s characteristics pose a potential challenge to effectively educating members about climate change. Nevertheless, over several years, the NWF reached out to hunters and anglers to educate them on climate change through an extensive training program in 35 states. The goals were to address their skepticism about climate change, improve their capacity to discuss the subject, and motivate them to support climate change legislation and other government initiatives.

The NWF directly tested different content and visual presentations in pilot courses attended by selected leaders of state and national hunting and angling organizations. The participants suggested several approaches to be included in the courses: (1) use local rather than international or even nationwide examples of global warming’s effects, (2) stay sharply focused on habitat and wildlife when educating about problems and solutions, and (3) have a format that allows ample time for participants to describe their own observations and experiences. After incorporating these suggestions into the training materials, the program began to show signs of success. For example, as trained cadres of leaders began to talk to others in their respective states, there were evident shifts in hunter and angler support for policy reforms. Organizations that had been reluctant to support climate change legislation or even to admit there was a problem started to become advocates. When the NWF brought hunters and anglers to Washington, DC, to talk with congressional leaders, more than 90 of 100 participants participated as a result of relationships that they had formed during their NWF training. The training program and the relationships it fostered also contributed to 670 national, state, and regional hunting and fishing groups signing a letter to the 111th Congress urging passage of the American Clean Energy and Security Act.1

Based on this success, the NWF staff used survey research to identify and develop training aligned with the cultural sensitivities, conceptual frames, and informational needs of several other constituencies. Training was targeted to the unique interests and concerns of environmental and civic activists, master gardeners, conservative faith-based organizations, watershed conservationists, land trust leaders, birders, university groups, coastal wetland conservation organizations, and business leaders. For each community, the training had three goals:

____________

1The U.S. House of Representatives approved the act in June 2009, but the bill died in the Senate.

1. educate key members on the basic science of climate change,

2. familiarize them with solutions to the problems of greenhouse gas reduction and natural resource adaptation, and

3. win their support for taking action on climate change, both personally and in terms of policy reforms.

Coyle said that aligning the training with each group’s conceptual frames and concerns was critical to inspiring the diverse groups to be more supportive of climate change actions and reforms. For example, surveys of Christian Coalition members indicated that the training program should frame the value of learning about climate change around energy independence, self-determination, and caring for God’s creation.

Faith-Based Groups

Greg Hitzhusen (Ohio Interfaith Power and Light) opened his remarks by explaining that he is both a researcher and education practitioner engaged with faith-based communities on issues of climate change and environmental ethics and education. He described his work with Interfaith Power and Light (IPL), the largest faith-based climate change organization in the United States, which works with more than 10,000 congregations in 38 states.2 He noted that the community of faith-based organizations is growing to include the National Religious Partnership for the Environment, the National Council of Churches Eco-justice Programs, the Evangelical Environmental Network, and the Coalition on the Environment in Jewish Life.

Hitzhusen provided several examples of successful climate change education efforts involving faith-based communities. The Cincinnati Archdiocese was the first signatory to the Catholic Climate Covenant, also called the St. Francis Pledge to Care for Creation and the Poor. The pledge asks Catholic individuals, parishes, and congregations to pray about climate issues; learn about climate change; assess what they can do, for example, an energy audit of church or home; act on that assessment; and advocate and talk to legislators about the importance of these issues.

To help the archdiocese achieve these goals, Ohio IPL assisted in setting up a Climate Change Education Day, focusing on what individual congregations could do to respond to climate change. The response was much larger than expected, with participation from approximately 67 churches. At the same time, the Greater Cincinnati Energy Alliance created a fund to help nonprofits retrofit their buildings for energy efficiency. They picked up on the education day event, realizing that old churches

____________

2For more information, see http://interfaithpowerandlight.org.

were a prime target, as they generally are not energy efficient. Today, 28 congregations in the Cincinnati area, including a mosque, a Jewish day school, and several Christian churches, have received funding of up to $15,000 to retrofit their buildings. In addition, the education day led participants to visit their legislators—both in the Cincinnati area and in Washington, DC—to advocate for climate change policy reforms.

Hitzhusen pointed out that this successful example raises basic principles for effectively communicating about climate change. The first principle is to work within the values of the community, as the Catholic Climate Covenant does. The second principle is to touch people through their hearts rather than solely through their heads, and to recognize that multiple values matter. The third principle is that, although it is essential to emphasize values when working with faith communities, overlapping concerns must also be considered. For example, it can be valuable to frame climate change not only as a moral issue but also as a way to save money.

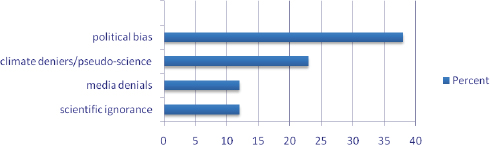

In closing, Hitzhusen discussed findings from a survey of directors of the state affiliates of IPL (Hitzhusen, 2010), who identified several key barriers to the acceptance of climate change information in faith-based audiences (see Figure 3-1). The respondents most frequently identified political bias or partisanship as a barrier, followed by the influence of climate deniers and pseudo-science (Hitzhusen, 2010). State directors also reported that, across audiences, messages framed in terms of certain values, including stewardship and eco-justice, were successful (see

FIGURE 3-1 Barriers to acceptance of climate change information in faith-based audiences.

NOTES: IPL directors identified several key barriers to the acceptance of climate change information in faith-based audiences. Political bias or partisanship was cited by 38 percent of the directors; the influence of climate deniers and peddlers of pseudo-science was cited by 23 percent; vocal deniers in the media were identified by 12 percent, as was scientific ignorance among Americans.

SOURCE: Hitzhusen (2010).

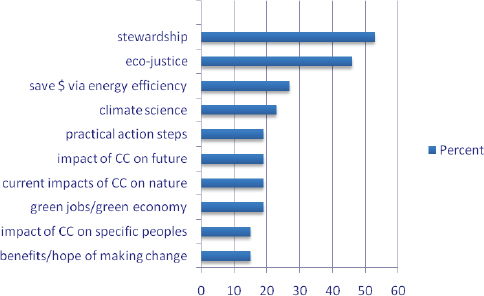

FIGURE 3-2 Most successful and resonant climate change (CC) messages perceived by IPL state directors as delivered to faith based audiences.

NOTES: A total of 53 percent identified basic stewardship; 46 percent a basic eco-justice message; 27 percent emphasized a message of saving money through energy efficiency; 23 percent identified the science of climate change; 19 percent identified each of the following: practical steps to help respond to climate change, the impact of climate change on future generations, current observations of the impact of climate change on the natural world, and green jobs/green economy opportunities. A total of 15 percent emphasized personalized messages about the impact on specific people(s) or the benefits and hope that come from making change.

SOURCE: Hitzhusen (2010).

Figure 3-2), whereas those framed in other ways (e.g., scare tactics, technical descriptions of the climate cycle) were consistently ineffective (see Figure 3-3).

The Business Community

Katie Mandes (Pew Center on Global Climate Change) explained that the Pew Center on Global Climate Change’s primary mission is to engage the business community on climate change issues, providing credible information and workable solutions. The Pew Center realized from the beginning that solving climate change would never happen without the positive involvement of the business community. In the 1990s, when the center started its work, the issue of climate change was already polarized, with

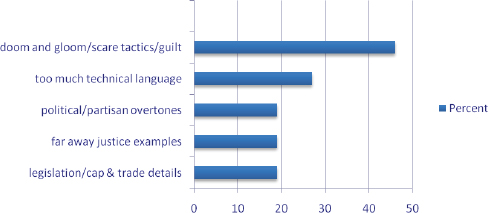

FIGURE 3-3 Ineffective messages identified by IPL directors.

NOTES: A total of 46 percent said that “doom and gloom,” “scare tactic,” and “guilt trip” messages do not work; 27 percent found too much technical language ineffective; and 19 percent cited each of the following: talking about climate change in a political way or with partisan overtone, giving environmental justice examples from faraway places like Africa or Bangladesh, and details about legislation or talk of “cap and trade.”

SOURCE: Hitzhusen (2010).

the mainstream business community on one side and the environmental community on the other.

From 13 corporations that signed on at the start in 1998, the program has grown to work with 46 large companies, with combined revenues of $2.5 trillion and over 4 million employees. Because these companies come from a variety of energy-intensive sectors, including manufacturing, chemicals, and agriculture, they may not all come out as “winners” in a changed energy and policy landscape. In its work with the corporations, the center’s primary goal is to work with these businesses to elicit change in federal policy, but also to provide assistance with implementing changes in company processes and technologies.

Although the center historically provided research and analysis to help chief executive officers make informed decisions, in recent years the companies have requested it to work with their employee base. In response, the center devised an employee engagement program called Make an Impact—Save Energy, Save Money, Save the Environment. The goal of this program is to support existing sustainability goals and link a corporation’s employees to the communities in which it operates. For example, employees were given access to a carbon calculator so they could calculate their home emissions, learning more about their carbon footprint

and personal impact on the environment. The corporations hoped the lessons learned would transfer into the work environment. The program also educated employees on programs already in place in the companies. The goals of this part of the program were to weave sustainability into the fabric of the workplace and empower employees to be part of the solution to climate change.

Mandes explained that she quickly learned about the importance of framing appropriate messages. For example, blue-collar workers across the country are not interested in being told what to do by somebody from Washington. To engage this audience, she frames climate change in light of their concerns, which may include energy security, energy independence, saving money, or stewardship of the earth. Following this framing, the center provides the workers with information on energy use and tools and resources to help make positive changes. The information is localized and distributed by company managers and other community members.

Mandes ended by saying that, although climate change remains a polarizing issue in the United States, there are ways to communicate effectively about the challenges and engage government, business, and individuals in finding solutions. She noted that peer-to-peer learning is very effective for climate change education.

The Media

Heidi Cullen (Climate Central) explained that Climate Central, a nonprofit science and journalism organization, tries to localize the issue of climate change. She said that one goal of climate change education is to engage the American public in considering what each individual can do to address the problem of climate change. The basic education challenge facing the climate science education community, she said, is that a relatively small group of people (climate scientists) strongly suggests that burning fossil fuels to power the modern economy is extremely harmful to the climate over the long term. This small group is asking the much larger public to reconsider the reliance on its primary energy sources (fossil fuels) and focus increasingly on sustainable energy resources. Because climate educators are asking a great deal of the American public, they need to build a strong and clear case for action.

Cullen explained that, during her transition from a career as engineer and climate scientist to an on-air climate expert with The Weather Channel, she received a crash course in communication through the news media. Ultimately, she learned that storytelling was the only way to cultivate and grow an audience that is both engaged and passionate. In her experience, there are three components to creating successful content:

1. Knowing your audience and what it cares about.

2. Building a strong, personal narrative that speaks to your audience.

3. Providing clear, actionable takeaways.

Cullen described three websites illustrating these principles. The first was created by the newspaper The Tennessean during an episode of national flooding. The second, called Black Saturday and produced by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, is an interactive website that can be viewed as a map, a timeline, or a narrative to help users understand the devastating fires that took place in Victoria, Australia, in February 2009.3 The third, Climate Matters, was created by Jim Gandy, chief meteorologist with WLTX television in Columbia, South Carolina; it is a series of 30-second segments designed to help the audience understand that climate change already impacts their daily lives.4

Cullen also emphasized that effective communication strategies will always be somewhat different for different audiences and across different platforms. At Climate Central, they work across print, TV news, and web platforms to capitalize on events that make it into the news cycle and therefore grab the attention of the public. For example, by seizing on extreme weather events, there is a tremendous opportunity to reach large portions of the public at key moments.

Cullen described a successful tool for providing data created by Climate Central: infographics that seize on breaking news and provide a “climate context.” They are consistently among the most popular items on the Climate Central website and are frequently cross-posted to other websites. To reach professional audiences, Climate Central developed a website called Climate Center, which mirrors ESPN’s SportsCenter. Climate Center provides 2-minute segments on such topics as weather statistics for specific cities, products from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, forecasts, outlooks, and the local impacts of such events as El Niño and La Niña. These segments are released through Climate Central’s partners and picked up by other sites that deliver climate change information.

IMPLICATIONS OF AUDIENCE SEGMENTATION STRATEGIES

Elaine Andrews (University of Wisconsin–Madison) approached the question of audiences in terms of how they function in communities, whether as neighbors, coworkers, or members of the same club or organization. Communities may be based on the place where one lives, on

____________

3See http://www.abc.net.au/innovation/blacksaturday/#/stories/mosaic.

one’s interests, one’s work or hobbies, or one’s sense of identity. She asked the workshop participants to consider Karen O’Brien’s use of integrative theory to analyze climate change (O’Brien and Hochachka, 2010). O’Brien sees climate change not simply as an environmental problem, but also as an issue involving human development, social justice, equity and human rights, and the capacity of individuals and communities to respond to an external threat. Andrews addressed three questions:

1. How can groups of like-minded people function to bring leadership and change?

2. How can scientists and educators identify and access these groups of like-minded people?

3. What educational and engagement strategies are effective in building effective public responses to climate change?

Andrews noted that, although there is no shortage of information and education, the real challenge for climate change educators is to take advantage of the scientific and opinion research to create more sustainable communication strategies. Such strategies recognize that people learn by participating in social systems and not just by receiving information, that social systems are structured by cultural tools and norms, and that learning involves affective and motivational factors.

Andrews presented slides depicting increases in global surface warming and greenhouse gas emissions, mitigation, and adaptation as a reminder that audiences come from a wide range of perspectives and relate differently to different strategies for mitigation and adaptation. She also highlighted that looking at audiences from the viewpoint of how different sectors contribute to greenhouse gases (some through natural processes) can be helpful in constructing decision-making processes about choosing audiences and thinking about how to work with them.

She identified four strategies to lead effective climate change education:

1. continue to identify the various communities with a stake in climate change,

2. develop learning and action networks of communities,

3. implement proven educational and decision support strategies, and

4. achieve a high level of social engagement and action.

Sharing an idea highlighted in a special issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment: Connectivity (June 2008), she closed by emphasizing the need to bring together communities and organizations with a stake in cli-

mate change, such as in the cooperative extension system, and to connect scientists with all varieties of communities.

IMPLICATIONS OF RISK COMMUNICATION RESEARCH

Wändi Bruine de Bruin (Carnegie Mellon University) explained that she works with experts in various fields—including engineers, economists, health practitioners, and scientists—to help them understand how to communicate with the public and how people make decisions. She observed that experts are trained to talk about their specific knowledge within their communities, but rarely do they have training in communication with people outside their field.

Bruine de Bruin pointed out that, although there have not been extensive literature reviews on successful strategies in climate change communication, there have been extensive studies in the domain of public health communication. In public health, the standard practice is to conduct a randomized controlled trial to test whether a particular risk communication is effective. Meta-analyses of such trials, which provide information across many studies as a way to discern patterns of effects, have identified several features of successful communication: it is developed by experts from multiple domains, based on extensive research on what the audiences want and need to know, and designed to teach not only basic facts but also how people can change their behavior.

To illustrate the need for an action-oriented approach to risk communication, Bruine de Bruin used an example of the national threat-level system. The system shows the current national threat level through a series of colors, with the basic message to keep traveling but be extra careful when a color changes to a higher threat level. At the time of the workshop, the threat level was at yellow, which indicates an “elevated” level of threat.5 However, this system does not provide travelers with an understanding of what the color means, what to do when the color changes to protect themselves from risk, or what steps they should take to travel safely. Therefore, the information provided does not provide a useful mechanism to help individuals make more informed decisions as they travel.

In the context of climate change, Bruine de Bruin reiterated that studies have found that different audiences have different information gaps and misconceptions and want to know different things. Even those who are convinced of the reality of climate change do not necessarily know how to change their behavior. Surveys show that most people believe

____________

5Since this workshop was held, the color-coded Homeland Security Advisory System has been replaced by The National Terrorism Advisory System (see http://www.dhs.gov/files/programs/ntas.shtm).

that the most important steps to save energy at home include turning off the lights or turning off the thermostat on the air conditioning unit. In fact, however, they might save more energy by installing a programmable thermostat or energy-efficient light bulbs or adding insulation. She emphasized the value of drawing on findings from other areas of risk communication for use in climate change education.

AUDIENCE SEGMENTATION STRATEGIES:

PANEL DISCUSSION

Following the panelists’ individual remarks, moderator Blockstein engaged them in a panel discussion.

In response to a question, Cullen discussed the work of Climate Central in several states and regions. In Georgia, for example, Climate Central focused on coal, the risk of associated climate impacts, and carbon-capturing storage technology. In the state of Washington, it highlighted forest fire risks caused by the local impacts of climate change. She also explained that Climate Central developed a case study of NASA satellites tracking sea ice melt in Greenland to show people the concrete evidence underlying scientists’ findings that sea ice is melting.

Blockstein referred to the successful energy-saving project in Kansas discussed earlier in the workshop (Kaufman, 2010; see Chapter 2), in which climate change was not directly addressed. He asked the panelists if they believe it is best not to use the term “climate change” when much of the audience would fall into the doubtful and dismissive categories identified previously by Leiserowitz (Leiserowitz and Smith, 2010; Maibach, Roser-Renouf, and Leiserowitz, 2009).

Hitzhusen responded that various IPL state directors have found that certain regions of the country have a higher percentage of people from each category. In the Northeast and the Midwest, most IPL audiences include few skeptics and are mostly comprised of the “concerned” group. In southern and western states, IPL directors encounter a wider range of views about climate change, and they assume that those who attend IPL programs generally belong to the concerned group, whereas others who do not attend are assumed to be skeptical.

Hitzhusen stressed that these perceptions about audience segments are based on the IPL directors’ outreach to particular religious communities and not on a random sample of the public in a region or state. Various individuals may fall into any of the six audience segments identified by Leiserowitz (Leiserowitz and Smith, 2010; Maibach, Roser-Renouf, and Leiserowitz, 2009), but they all belong to a community that shares a set of religious beliefs. In general, the communities that IPL reaches are respectful of each other, regardless of their views on climate change.

There is a communal bond among the members on which IPL leaders try to capitalize in their outreach efforts.

Hitzhusen stressed that IPL directors, when communicating about climate change, emphasize the common values that draw their audiences together. They focus their messages on stewardship and justice issues associated with climate change that resonate with the values of faith communities. In particular, when working with skeptical audiences, IPL directors have said that they do not try to drive home a message about climate change. Instead, they talk about environmental stewardship and why people of faith think environmental stewardship is important.

Coyle said that, in his view, educators need to directly address climate change when communicating with doubtful and dismissive audiences. He stated, “You have to talk about climate in a way that makes sense within the community” you are trying to reach. In addition, he encouraged the workshop participants not to give up entirely on people who fall into the dismissive category, reminding them of the NWF’s climate change training with hunters and anglers. The training program was successful, as many of the hunters and anglers later encouraged their governors to support legislation on climate change issues.

Cullen reinforced Coyle’s message, recounting that at a recent meeting she was asked whether educational efforts should stop explicitly focusing on climate change, and she replied “absolutely not.” Cullen stated that it is very important for climate change educators not to lose the science message. She pointed to research by Jon Krosnik at Stanford (ABC News/Planet Green/Stanford University, 2008) suggesting that the single strongest predictor of concern about climate change is the belief that it is caused by human activity. This research indicates the importance of helping people understand the connection between human activity and climate change.

Bruine de Bruin cautioned that one strategy often suggested for engaging doubtful and dismissive audiences—framing the message in terms of saving money by reducing energy use—may not translate well for people concerned about climate change. Her research with graduate student Daniel Schwarz found that people who have relatively strong pro-environment attitudes become less motivated to enroll in energy saving programs when these are described as saving money (Schwartz et al., 2011). This finding is akin to many studies that have shown that providing extrinsic rewards, such as paying people for good behavior, can lower intrinsic motivation, as study participants begin to feel that their actions are motivated by an extrinsic motivation, such as earning or saving money (Frey and Oberholzer-Gee, 1997; Gneezy and Rustichini, 2000). These examples add to the case for the value of audience segmentation.

Andrews observed that the first step in developing effective educa-

tion is to research the audience, including its values, motivations, and understanding of climate change. Education activities can then be tailored to what is appropriate. Andrews described an approach called “appreciative inquiry” that she uses when working with local government officials in Wisconsin. She asks people in the room to talk about their experiences with climate change. This technique promoted meaningful discussions of climate change among individuals with a wide range of perspectives.

Audience Comments and Questions

Roberta Johnson (National Earth Science Teachers Association) asked Hitzhusen how social justice related to climate change is perceived by faith communities. He responded that, although environmental and climate change issues have been part of the “culture wars” for some time, a Christian Coalition voter guide for the McCain-Obama election showed that the two candidates differed on every issue except climate change. He added that the biblical tradition provides a particular approach to the concept of justice and that most faith communities see social justice as an important issue. Although there is also a long history of faith communities being involved in environmental issues, in the past groups have struggled to convince people that the environment was a serious moral, ethical, and religious issue.

Today, Hitzhusen stated, the IPL speaks about climate change as a social justice issue by illustrating the disproportionate impacts of climate change on the poor and the vulnerable. When framed this way, messages about climate change resonate with faith communities’ dedication to addressing moral and social justice issues. He noted that both the National Council of Churches and Catholic Church groups address climate change primarily in terms of eco-justice. He again stressed that IPL leaders do not seek out hostile audiences—they work primarily with faith communities that are interested in climate change as an issue of justice and stewardship.

Kit Batten asked how audiences—such as these faith communities—that are engaged with climate change issues could be leveraged to inspire other audiences. Cullen suggested that, when climate change educators consider how to prioritize audiences, they could focus first (or primarily) on the audiences that they know the most about. For example, in her work at Climate Central, she strives to identify issues that resonate with people at the local level, such as a message about fly fishing for trout in Montana.

Edward Maibach (George Mason University) agreed with Bruine de Bruin’s earlier point that research on public health communication can serve as a valuable resource for climate change education. Reviews of many public health education programs have been published in journals,

and he suggested that climate change educators should similarly review and evaluate the impacts of their work. Maibach observed, “The descriptions of programs that the panel has provided have been inspirational; now we desperately need case studies or evaluations of these programs in the literature.” Blockstein responded that a new interdisciplinary journal of environmental studies and sciences (Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences6) being launched in 2011 would provide a venue for publishing such program evaluations and related research.

Joshua Rosenau (National Center for Science Education) added that the National Center for Science Education focuses on defending the teaching of evolution in public schools. He observed that the arguments raised regarding the teaching of evolution are similar to the arguments being raised regarding teaching about climate change.

Blockstein concluded the general discussion by mentioning that the National Science Foundation has funded and is continuing to fund multiple climate change education projects.

BREAKOUT GROUP DISCUSSIONS

During the breakout session, the carousel brainstorming technique was again used to facilitate discussion. To initiate the conversation, the steering committee provided the following guiding questions:

1. Thinking of all the general public’s identified on day one of the workshop, what do you know that has/has not worked to reach them on a topic like climate change?

2. How could we scale up exemplary programs?

Ann Bostrom listed the major takeaway messages from the breakout group discussions of the first question. She began by observing that there is no silver bullet for climate change education. No single message, program, resource, or activity will be effective in reaching the broad goals of climate change education for all audiences. Instead, it is important to frame education efforts differently for different groups and align them with each group’s values. That said, she outlined some general guiding principles that could be applied in many situations:

• It is valuable to understand where people get their information and what sources of information they trust. This understanding makes it possible to leverage existing information networks, communication nodes, or influential individuals in communities when

____________

6See http://aess.info/ [September 2011].

conveying a message about climate change. Some participants observed that a growing percentage of the population obtains information from social networking websites or media channels and emphasized that people often trust the social network sites or media that their peers suggest. In fact, one survey found that individuals who fall into the dismissive category (as defined by Leiserowitz, Maibach, and Light, 2009) most trust information from friends and family (or the resources they recommend).

• Once the appropriate communication channels have been identified, storytelling is a powerful strategy for engaging audiences. By using meaningful and locally relevant stories, climate change education efforts can align with local needs, values, and interests. The stories can highlight tangible events and draw on the audience’s experience. Climate change educators can also directly engage individuals in storytelling, to help them share their personal experiences with the impacts of climate change.

• Although connecting to local events is an effective way to align education efforts to the audience’s interests and values, it is also important to connect these local events to the larger, global nature of climate change. Several participants noted that one way to make this connection is through citizen science initiatives, which allow individuals to explore the local impacts of climate change and connect to others around the world who are experiencing similar and different impacts. Another benefit of citizen science initiatives is that they engage individuals in the processes of science. To engender trust in information about climate change, individuals need to understand both the scientific results and how those results were produced. Citizen science initiatives provide opportunities to learn about both.

• It is important for climate change education to provide opportunities for understanding both problems and their potential solutions. Education programs need to engage people in individual as well as community actions, and organizations involved in climate change education need to practice what they preach through sustainable activities and behaviors.

Turning to the second question, about the keys to scaling up exemplary programs, Bostrom noted that some of the breakout group discussions focused on funding issues, partnering, and developing and sharing evidence-based practices. The groups discussed the need for scale-up to develop through top-down as well as bottom-up processes. Top-down leadership could include sharing the most effective education strategies or policy changes—such as regulations or incentives—to require or encour-

age people to take action to mitigate impacts of climate change. Bottom-up processes include building momentum by engaging communities and utilizing networks to extend community efforts.

On the topic of funding, some participants suggested that more funding sources need to be encouraged to support climate change education efforts. In addition, some suggested that funding agencies learn how to finance programs that encourage people to make investments that yield long-term benefits—such as equipping homes with solar panels. Funding programs could lead to wider use of solar panels, reducing consumption of fossil fuels over the long term.

Some breakout group participants expressed the view that climate change education programs are more like to succeed and grow if education organizations create partnerships in the community they are targeting. For example, the green schools movement grew by establishing local partnerships that brought individuals and organizations together to address shared concerns about school improvement, energy consumption, and other local issues. In considering which programs should be scaled up, people said, it is important to first understand which ones are most effective. Although many participants were skeptical about using standard evaluation methods to measure the effectiveness of climate change education programs, they thought that the field needs evidence to inform the design of strategies and programs. Developing such evidence will require program evaluations, including careful thought about expected goals and outcomes. Climate change educators could also draw on the existing research on climate change education and on public education campaigns more generally.

Finally, many of the breakout groups discussed the difficulty of sharing or finding out about successful programs, practices, presentations, messages, or strategies. Participants noted that, although there are many online sites with links to numerous climate change education resources, these sites rarely review the resources or describe what programs have been successful and why. When some participants said that a single clearinghouse with this sort of information would be invaluable, others commented that the National Science Foundation is funding the creation of such a clearinghouse—the Climate Literacy Education Awareness Network (CLEAN) Pathway.7

___________