4

Where Does the Breastfeeding Campaign Go from Here?

The final panel of the workshop, moderated by James Lindenberger of the University of South Florida, was designed to examine what might happen next with the Loving Support campaign. Panelists offered suggestions from a number of perspectives. Claudia Parvanta spoke on how social marketing principles could be applied to the new campaign. Jay Bernhardt discussed new communication tools that can play a role in engaging mothers and other stakeholders. Cathy Carothers, relying on feedback from seven state programs, suggested several implementation tools needed by local WIC staff to move forward. Katherine Shealy discussed the potential benefits of—and many possibilities for—strategic community-based partnerships. Kiran Saluja identified a number research gaps as well as some existing research, especially at the state and local level, that could be better utilized. Dawn Baxter discussed the use of evaluation as a planning tool in designing or updating the campaign. She also emphasized that evaluation makes it possible to measure impact and to implement quality improvement.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR PROGRAM COMPONENTS, MESSAGES, AND IMAGES

Presenter: Claudia Parvanta

Claudia Parvanta, a professor of anthropology and chair of the Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences at the University of the Sciences, Philadelphia, said she agreed with other speakers who called for a campaign

that encompasses an aligned set of actions designed to achieve a goal, rather than simply an advertising campaign.

The Message and the Brand

Campaign messages should support a goal. Parvanta characterized messages as memorable, explanatory words or images that convey an idea and communicate whatever the person creating the message wants people to know, feel, or do. Messages are crafted after concepts are tested; the concepts, in turn, should be derived from specific behaviors to be promoted. More than ever, Parvanta said, the messages depend on the medium that will carry them.

As an example of a campaign that targeted a behavior, Parvanta presented a campaign that was developed to encourage women capable of becoming pregnant to take folic acid. She offered two very different concepts that could be used to promote this behavior that were based on research with this population: one for women who have or want to start families soon and another for women of child-bearing age who do not plan on getting pregnant soon. The words and images used to promote folic acid differed depending on the intended audience.

The brand represents a promise made to consumers by a company or organization. A brand delivers on its promise, Parvanta said, by having every single activity linked under it to support the idea. In this case, she said, Loving Support is the brand, and “makes breastfeeding work” is the brand’s promise. WIC tries to deliver on the promise through program service delivery (to include staff, facilities, hours, and communications) as well as through community support, such as the legislative environment, hospital and physician practice, peer network, and community attitudes.

When launched, the Loving Support campaign was based on formative research and then-leading theories in health communications. For example, research showed that the campaign strategy should emphasize the emotional benefits of breastfeeding for families, so this is the focus rather than the health benefits of breastfeeding. Parvanta advised building the campaign from the ground up for maximum brand integrity, with community and family attitudes, the birthing hospital policies, and staff and community physicians providing a strong base so that WIC can make breastfeeding work. The question is now, what research is needed to update the positioning and marketing mix for WIC breastfeeding promotion?

Theoretical Considerations

Parvanta suggested thinking deeply about how the audiences will be defined, what kind of change is desired from these audiences, and how to motivate them.

In the years since the campaign began, much has been learned about self-efficacy in breastfeeding, Parvanta said, although she added that she has not yet seen many of these lessons applied. For example, research has shown that women scored higher on breastfeeding self-efficacy scales at 2 days and at 4 weeks postpartum if they had observed breastfeeding role models through videotapes, if they received praise from their partners for breastfeeding, or if their own mothers had significantly higher levels of breastfeeding self-efficacy. In contrast, women who experienced physical pain or received professional assistance with breastfeeding difficulties had significantly lower levels of self-efficacy (Kingston et al., 2007). These findings and others on self-efficacy have implications for lactation counseling.

Parvanta also suggested revisiting the Stages of Change model, which posits that people go through stages (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance) on their way to behavior change rather than changing all at once. Pregnancy gives women several months to move through the initial stages, but the real test comes in the first days after giving birth. Parvanta recommended applying the model more specifically to the change period at that critical point in time.

Risk-communication theories can also inform the new campaign. Parvanta urged paying attention to fears about breastfeeding. The Extended Parallel Process Model posits that the mother may protect herself against the “fear of the threat” rather than against the threat itself. For example, if a mother is afraid she will not have enough milk (fear of the threat), she may start formula feeding, even though the threat itself does not occur.

Risk communication is not intuitive. One principle of risk communication, known as the Sandman seesaw (Sandman, 2007), suggests dealing with ambivalence about a behavior change like breastfeeding by “[taking] the seat opposite from what you want your participant to be doing.” In other words, on a seesaw, if you want your partner to go up, you need to go down. In risk communication, this means acknowledging and exploring the concerns that women have about breastfeeding by allowing them to consider the possibility of alternatives—not simply by telling them that these alternatives are inferior. There may be conflicts between what gatekeepers believe and what mothers need to believe in order to breastfeed, such as the role of choice and their decision, availability of a breast pump and formula, or acknowledgment that they are not failures if they resort to formula once or twice.

Segmenting Audiences

Parvanta suggested segmenting audiences by the desired behavior change—that is, rather than sorting an audience by demographic group, one should think about the specific objective for a segment and what motivates change for members of that segment. Audience segments might include the participant herself, her key influencer, her family, her community, and health professionals. Important segments to understand include both fathers and grandmothers, who for various reasons may want to separate the mother from the baby and thus may discourage breastfeeding. Parvanata recommended that special attention should be directed to first-generation Americans who have come from different cultures, as some of them may see bottle-feeding as something they could not do in their country of origin but which is the norm in the United States. Healthcare providers also play a very large role, and, in particular, maternity care nurses are often not supportive of breastfeeding.

Four Suggestions for FNS

Parvanta wrapped up her presentation with final suggestions to FNS:

- If available, put funds into support for community resources and for lactation counseling personnel and hotlines.

- Focus on public opinion and healthcare providers. Without support from the public and healthcare providers, the campaign will be difficult to sustain.

- Explore risk communication and related theories.

- Match new media to the audience and behavior change objectives.

LOVING SUPPORT 2.0: LEVERAGING NEW MEDIA

Presenter: Jay M. Bernhardt

Since the launch of the Loving Support campaign, a variety of new communications technologies have been developed for creating and sharing, interactivity and engagement, and collaboration. Jay Bernhardt, a professor at University of Florida, noted that people are no longer only passive recipients of information, but rather they are active, creative participants. According to Bernhardt, 2.0 communication1 harnesses the power of groups

__________________

1A phrase referring to the use of use of blogs, wikis, and social networking technologies for communication purposes. It is based on the term “Web 2.0” believed to be coined by Tim O’Reilly referring to information technologies that harness active participation to improve themselves over time.

of people to produce better outcomes. Women who turn to social media to share their own stories are an important, influential source of information for other women making decisions. The question is how to use this technology to make a breastfeeding campaign more effective.

Crossing the Digital Divide

Bernhardt presented data from the Pew Internet & American Life Project (2010) about communication trends and usage in the United States. Internet usage is high (95 percent among adults ages 18–29 and 87 percent among adults ages 30–49), although its growth has flattened out in recent years, in part because the price for broadband access has not dropped as much as it has in other developed countries. What people do online is changing rapidly. Reading text online has declined, while the amount of time spent playing games and watching videos has increased. The implication, Bernhardt said, is that people are much less likely to read sites full of text than to watch short entertaining or educational videos. Social networking, downloading and listening to music, and microblogging (such as with Twitter) are also increasing in popularity. According to the Pew data, in May 2010 86 percent of adults ages 18–29 and 61 percent of adults ages 30–49 used social media, up from 16 percent and 12 percent, respectively in September 2005 (Madden, 2010).

While increasing percentages of the population have Internet access, Bernhardt warned that a digital divide still exists. Only two-thirds of the population has broadband access, which he characterized as not only too low but also a “missed opportunity for public health in the U.S.” Significant portions of the general population do not have traditional Internet access. In contrast, he said, cell phones are “perhaps a great equalizer in terms of digital access.” According to the wireless telecommunications association CTIA, there were 303 million wireless subscribers in December 2010 (CTIA, 2010). The use of text messaging in particular has skyrocketed. African Americans and Latinos lead whites in their use of many mobile data applications (Table 4-1). To Bernhardt the take-home message is that while audiences vary in their access to the Internet, mobile technology may help health information cross the digital divide to hard-to-reach populations.

Bernhardt listed what he sees as the advantages of more interactive and participatory “2.0 communication programs”: increased and sustained reach; deeper audience relevance, involvement, and engagement; scalable and affordable interventions; and the ability to perform measurement and evaluation through data mining and automated monitoring. While more traditional forms of media should not be abandoned, using these new forms of communication can potentially lead to more effective programs, with

TABLE 4-1 Use of Mobile Technology: African Americans and Latinos Lead Whites in Their Use of Mobile Data Applications

| Own a cell phone | All adults (%) | White, non-Hispanic (%) | Black, non-Hispanic (%) | Hispanic (English-speaking) (%) | ||

| 82 | 80 | 87 |

87 |

|||

| % of cell phone owners within each group who do the following on their phones | ||||||

| Take a picture | 76 | 75 | 76 | 83 |

||

| Send/receive text messages | 72 | 68 | 79 |

83 |

||

| Access the internet | 38 | 33 | 46 |

51 |

||

| Send/receive email | 34 | 30 | 41 |

47 |

||

| Play a game | 34 | 29 | 51 |

46 |

||

| Record a video | 34 | 29 | 48 |

45 |

||

| Play music | 33 | 26 | 52 |

49 |

||

| Send/receive instant messages | 30 | 23 | 44 |

49 |

||

| Use a social networking site | 23 | 19 | 33 |

36 |

||

| Watch a video | 20 | 15 | 27 |

33 |

||

| Post a photo or video online | 15 | 13 | 20 |

25 |

||

| Purchase a product | 11 | 10 | 13 | 18 | ||

| Use a status update service | 10 | 8 | 13 | 15 | ||

| Mean number of cell activities | 4.3 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 5.8 | ||

NOTE: N = 2,252 adults 18 years and older, including 1,917 cell phone users.

*Statistically significant difference compared to whites.

SOURCE: Adapted from Smith, 2010. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, April 29–May 30, 2010 Tracking Survey. Reprinted with permission from the Pew Internet & American Life Project.

both the opportunity and the challenge to “get the right message to the right audience from the right source at the right time.”

Bernhardt suggested four steps in determining how to use new media for Loving Support. First, identify, understand, and prioritize the target audience segments. This, Bernhardt said, is the single most important thing to do. Second, determine the specific objectives for each audience, in terms of knowledge, skills, norms, behaviors, support, and resources. Third, determine the media access and use of each audience, both for traditional and new media forms. Only after the first three steps are completed should the fourth step be done: Develop and pretest the media mix and messages.

Although businesses routinely do it, public health programs are not so likely to leverage the range of available Web and mobile platforms (see Box 4-1). Bernhardt encouraged Loving Support to take advantage of existing resources, noting that text4baby (a mobile phone application also discussed by the next panel) and other tools offer exciting possibilities for

BOX 4-1 Available Web and Mobile Platforms

Web-Based Communication

Search engine optimization

Social networking sites

User-generated content

Blogging and micro blogging

Online streaming video

Mobile-Based Communication

SMS-based (texting) tools

Free “apps”

Mobile websites

Local and tracking tools

Practitioner Tools

Apps and mobile

SOURCE: Bernhardt, 2011.

improving the communication of messages. Bernhardt finished by discussing the innovative potential of leveraging mobile technology for offering “digital coaching” about breastfeeding to women in the field during the immediate hours after delivery.

IMPLEMENTATION TOOLS NEEDED BY WIC STAFF

Presenter: Cathy Carothers

When the Loving Support campaign was created in 1997, it used the implementation tools available at that time to address the barriers to breastfeeding. Cathy Carothers, co-director of Every Mother, Inc., reminded participants of the various approaches—the consumer information, the media used to raise public awareness, and the staff training—that were developed to overcome barriers to breastfeeding and create breastfeeding-friendly communities.

Issues Raised

When Carothers asked WIC staff to identify the most relevant issues to them in 2011, she found that there is now an emphasis on the impor-

tance of exclusive breastfeeding. WIC staff observed that breastfeeding mothers do not come back to WIC until they have started to use formula. (A new study [Gross et al., 2011] supports this observation, Carothers said.) Mothers are often excited about breastfeeding while pregnant, but, as Carothers put it, “All bets are off once that baby is born.” Hospitals’ policies can be a detriment to breastfeeding. WIC staff told Carothers that they feel ill-equipped to reverse the situation in which a woman leaves the hospital supplementing with formula. Mothers express concern, real or perceived, about a lack of breast milk, which leads many of them to wean early. Despite a national movement to support breastfeeding at the workplace, WIC staff report a different situation at the local level, where most low-wage settings that employ WIC mothers are not conducive to breastfeeding or milk expression.

Carothers said that WIC staff members have embraced the Surgeon General’s Call to Action and its support for making breastfeeding easier for new mothers through changing the environment of support from health care providers, family, employers, and the community. Loving Support can help create that support.

Recommendations from the States

To understand these issues and what WIC staff at the local level feel would be important in a new campaign, Carothers asked for feedback from seven state programs—those in New York, Texas, Iowa, Mississippi, Virginia, Michigan, and Washington. People in the state programs in turn talked with people at local agencies within their states.

Carothers reported that she received the following feedback concerning implementation tools needed in a new campaign:

- Recommended target audiences: While mothers should continue to be targeted, respondents suggested that the audience should be broadened to include hospitals, healthcare providers, employers of low-wage earners, and the general public.

- Media tools: Television and radio PSAs should continue, but they should be focused on the community support needed, rather than trying to get women to breastfeed. Respondents suggested that these ads run in cycles, not just during World Breastfeeding Week, and that they should also be available to post on YouTube or local websites.

- Social media needs: The respondents agreed, as was discussed throughout the workshop, that WIC mothers are communicating via texting and social media. Given that situation, Carothers said that it would be helpful to provide WIC staff with training on

how to use social media effectively; with templates for Facebook, texting, Twitter, mothering blogs, and other platforms; and with engaging YouTube video sound bites.

- Other tools: Several WIC staff said they found that brochures were often thrown away and not used. Thus they suggested that it would be useful instead to have such things as magazines targeted at low-literacy mothers, resources for fathers and grandmothers, a national website where mothers can get current information and links to local resources, materials in different languages (such as Spanish, Hmong, Chinese, and Vietnamese), and gifts like discharge bags. The Texas Every Ounce Counts Program, which uses more online materials than printed materials, was mentioned as a successful model.

- Resources for WIC staff: WIC staff were very positive about Grow & Glow training. They also asked for strategies on how to approach hospitals, healthcare providers, community groups (such as malls and other organizations), and employers of low-wage mothers. They requested training in how to conduct effective local campaigns and to use partners more effectively.

- Resources for the community: Respondents suggested adaptations of Grow & Glow for community organizations (for example, short lunch-and-learn training for community groups and more full-scale training for home visiting nurses). They also suggested Web-based physician tools, Business Case for Breastfeeding companion materials focusing on employers of low-wage women, and ready-made displays for the community.

Finally, respondents from the different state WIC programs suggested that it would be useful to have strategies and funding to help more WIC staff become International Board Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLCs), information and tools to share with Medicaid offices to get buy-in from that program to support breastfeeding, and sustainable funding to expand peer counseling. Carothers said that many respondents told her that peer counseling is “one of the greatest things to happen to the WIC program.”

STRATEGIC COMMUNITY-BASED PARTNERSHIPS

Presenter: Katherine Shealy

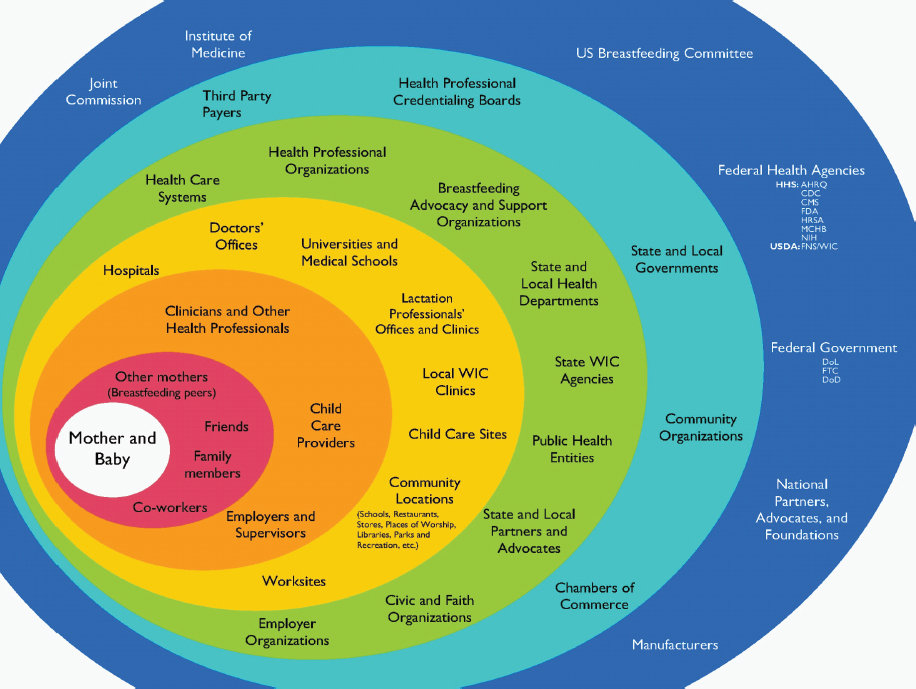

Throughout the workshop participants discussed the importance of partnerships. Katherine Shealy, public health advisor at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), said she wanted to explore further the role that community partners can play in the new Loving Support campaign

and posed the question, “What community partners provide opportunities for FNS collaboration, and what role can they play in Loving Support?”

Shealy said that her vision for a primary goal for Loving Support would be not to change mothers’ decisions about infant feeding but rather to remove the barriers that impair mothers’ abilities to carry out their decisions. Achieving this goal requires Loving Support to reach the settings, people, and groups that influence infant feeding decisions beyond mothers and their immediate circle of care, such as hospitals and employers. FNS has been a responsive partner in the community, Shealy said, but she recommended that the agency become a more proactive initiator of partnerships and an engaged contributor with “some skin in the game,” contributing financial and human resources to partnership activities that go beyond the traditional WIC clinical setting. With these thoughts in mind, she then explored what these strategic partnerships might entail.

Potential Partners

A variety of stakeholders, including the Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding, the National WIC Association (NWA) Strategic Plan and Six Steps to Breastfeeding, the White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity Report, the Business Case for Breastfeeding, the recently launched U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Partnership for Patients, and various other publications and activities, have said that partnerships are essential for success and list potential partners for Loving Support. These publications recognize that partnerships must be based on the socio-ecological model (a construct used by the CDC in promoting health behavior that considers the interaction between individual, relationship, community, and societal factors), and span agencies, programs, and program eligibility groups (including WIC participants, potential participants, and the wide community). Shealy noted that the Surgeon General’s Call to Action is based on the idea that most mothers in the United States want to breastfeed and everyone can help make it easier for them to do so. The document offers a number of action items concerning mothers and their families, communities, the healthcare system, employers, research and surveillance, and infrastructure.

National breastfeeding activists, such as the NWA and the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee, identify some priority partners based on how they support or impede mothers’ breastfeeding decision: birth hospitals and healthcare providers at the local level; breastfeeding coalitions, healthcare organizations, and health departments at the state level; and key federal agencies at the national level. The healthcare system includes everyone from the individual clinicians with whom a mother interacts, through hospitals and doctor’s offices to insurers, credentialing boards, the Joint Commission, and the American Hospital Association.

Shealy urged going beyond the “choir” (WIC and public health entities) to develop novel national and federal partnerships that “empower the local choir” to carry out its work: partnering with groups that influence mothers’ decisions, such as employer organizations, chambers of commerce, manufacturers, government agencies not involved with public health, universities, and medical schools. Partnerships that are “authentically strategic”—which Shealy defined as engaged in such a way that the entities accomplish more together than they could on their own—are challenging but necessary. As shown in Figure 4-1, the socio-ecological model mentioned above connects the mother and baby to these organizations and to the institutions that affect them.

Shealy identified some current partnerships already in place: the new Federal Breastfeeding Workgroup, the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee, the Breastfeeding Consortium, and text4baby, which provides free, text-based health information to pregnant women and new mothers in vulnerable populations. That initiative already reaches 500,000 women and has 138 outreach partners from businesses, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations. As an example of innovative ways that text4baby works with partners, Shealy said that wireless companies have agreed to allow subscribers to receive the texts from text4baby without those texts counting toward the mothers’ monthly limits. Text4baby partners also have access to customizable materials and tools, along the lines of what some WIC programs say they would like.

Shealy gave a few examples of effective WIC partnerships on the local and state level. In Mississippi, for instance, a WIC clinic at University Medical Center in Jackson has fully collaborated with the postpartum unit for 15 years. Mothers are certified prior to discharge and are already assigned to and can meet with a peer counselor. In north Georgia local WIC staff members work with carpet factories that employ large numbers of WIC mothers to establish workplace support programs. In New York WIC participates in program planning and activities in a CDC-funded obesity program, which ensures consistent messaging and shared resources. And in North Dakota WIC provides local support to coalitions, is involved with the state Business Case of Breastfeeding initiative, and partners closely with the Communities Putting Prevention to Work team.

Shealy concluded her presentation by emphasizing the benefits to FNS of working with partners in the new Loving Support campaign. Partners can amplify the messages that WIC mothers receive during their WIC interactions. They can help share the load so that WIC staff are more effective and can spend less time correcting inaccurate or incomplete information that mothers hear elsewhere, and they can lend credibility by echoing WIC’s messages prioritizing breastfeeding support. Some partners that Shealy identified as essential in a new campaign are federal and state

FIGURE 4-1 Organizations and institutions that affect mother and baby.

SOURCE: CDC/DNPAO, 2011. Reprinted with permission from CDC/DNPAO.

departments of labor, which can help with legislation requiring accommodations for breastfeeding mothers; local and state breastfeeding coalitions; hospitals; and organizations of healthcare professional, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics or the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

IDENTIFYING RESEARCH GAPS

Presenter: Kiran Saluja

Saluja returned to the podium to discuss what WIC needs to know about current perceptions of breastfeeding and the need for early support. It is important, she said, to learn not only about a mother’s perceptions but also about the perceptions of those around her, including healthcare providers, WIC staff, family, and friends.

Understanding Perceptions

It is important to understand the perceptions that these different groups have concerning a variety of topics, such as the following:

- Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months and the critical role of early support to make that happen: What does “exclusive breastfeeding” really mean? Does even one bottle in the first few days sabotage breastfeeding? What does “early support” really entail, and how can WIC reach out in the first 72 hours after giving birth?

- Continuation of breastfeeding: How can WIC mothers who take a fully breastfeeding package in the first month be prevented from coming in for formula in subsequent months? What is the best way to deal with the mothers and also the healthcare providers and public health clinics that may be giving them a different message about formula versus breastfeeding?

- Breastfeeding success: What are the salient predictors of resiliency and efficacy that will improve breastfeeding success? Talking with successfully breastfeeding mothers can provide insight about their common characteristics and about what distinguishes them from mothers who are not breastfeeding. Are some elements of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale more salient than others for different settings?

Every state WIC program has data that can be mined to answer some of these questions. Saluja suggested that USDA should provide resources

to the states so they can mine the data and possibly use it to answer some of their questions. For example, Saluja’s agency in southern California (the Public Health Foundation Enterprises WIC Program) evaluates everything: the new food package, breastfeeding rate variables, mothers’ perceptions about their hospital stays, and much more. The agency’s research demonstrated the impact of the new food package when it was reinforced with a policy of not routinely issuing formula plus staff training on that policy. Another survey looked at women’s perceptions of their hospital stay and the effect of hospital policies.

Sample Ideas from WIC Staff

Saluja passed along other suggestions for research that she heard from WIC staff around the country. Several people had suggested investigating what the WIC population understands about the risks of formula feeding. Some told her that “Many of our moms do not see the foods for themselves [the food package] as important as formula. . . . The [dollar] amount of the foods that they would get just doesn’t compute the same [as the value of formula].” Others pointed out that breastfeeding has to be something the mother believes in and values, beyond the incentive of the mother getting additional food or food for a longer duration. They suggested researching the role of images in WIC clinics and hospitals. Another suggestion was to look closely at the research behind “no bed sharing,” since safe bed sharing can help mothers continue to breastfeed.

DEFINING GOALS AND EVALUATING SUCCESS

Presenter: Dawn Baxter

Evaluation consultant Dawn Baxter encouraged participants to think of evaluation as a planning tool and not just the final step of a campaign. That means that people should make sure from the start that the information needed to determine success will be available at the end of the campaign. Baxter said that she was asked to address four questions: (1) how to identify behavioral and process outcomes; (2) how the USDA can establish baseline data; (3) what is required to develop an evaluation and monitoring plan; and (4) how evaluation and monitoring can be designed to accommodate budget, staffing, and other resources limitations.

Identifying Outcomes

In reviewing the current goals of Loving Support, Baxter noted that exclusive breastfeeding is not mentioned, although it is something that

many participants discussed during the workshop. Thus, the first question in a new campaign should be to determine whether the current goals are still relevant and what changes in the goals are needed.

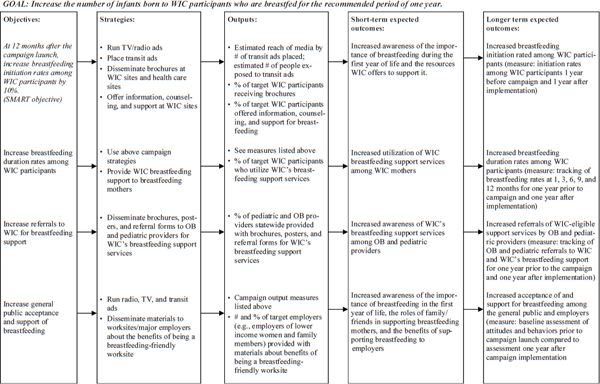

Baxter presented a sample logic model (Figure 4-2) based on the goal to “increase the number of infants born to WIC participants who are breastfed for the recommended period of one year.” Whatever specific goal is ultimately decided upon, Baxter advocated thinking through a similar logic model that covers measurable objectives, strategies to reach those objectives, outputs, and both short- and long-term outcomes. Knowing the outputs—for example, the percentage of participants offered support for breastfeeding or the percentage of healthcare providers given information about WIC’s breastfeeding services—can also help from a process perspective to catalogue what has been done and by whom, what materials were sent out, and who saw them. This would be especially helpful, she said, when different states use different components of the campaign.

The crux of an evaluation is defining the objectives. Baxter said the “gold standard” is to develop what are known as SMART objectives: specific, measurable, attainable/achievable, relevant, and time-bound objectives. For example, the objectives “increase initiation of breastfeeding” or “increase duration rates” need more definition in terms of how long it should take to implement a specific change. Similarly, the objective “increase public acceptance of breastfeeding” could be measured by determining the number of employers who receive information about the benefits of a breastfeeding-friendly workplace; gauging public attitudes through focus groups, surveys, and polling; or finding out the percentage of WIC participants who report support from their family members. In many cases, WIC programs have this information, and Baxter encouraged acting on it to make modifications as needed, rather than waiting for data to be compiled and published.

Baseline Data

Ideally, baseline data should be collected for a year before a campaign starts and for a year after its launch. WIC may already have these data in its archives, unlike many other organizations that are starting from scratch. States and local programs will probably need assistance compiling the data and ensuring sufficient consistency that the data can be compared. Moving forward, it will be important to communicate to the states what they need to measure for the campaign so that data collected by programs differently could be compared and analyzed.

FIGURE 4-2 Loving Support campaign logic model sample.

SOURCE: Baxter, 2011.

Developing an Evaluation and Monitoring Plan

The USDA needs a “big picture” strategy that includes objectives, measures, data sources, roles and responsibilities, a timeline, data collection tools, and an analysis plan, Baxter said. Monitoring the campaign involves tracking program activities, such as the materials distributed or the ads placed, as well as relevant outcomes, such as monthly referrals, initiation, or duration rates. Tracking activities and outcomes can help with continuous quality improvement and can also help identify and address problems in a timely way.

Evaluating with Limited Resources

To address the final topic, evaluation with limited resources, Baxter returned to the importance of planning in advance of the campaign. Planning an evaluation at the beginning of the campaign is easier and less costly than trying to put together an evaluation after the fact. The evaluation must be practical at the local level. This means developing measurable objectives, selecting measures that will work within operational constraints, and developing a system for collecting and tracking data over time; coding data in ways that are easy for staff to understand, track, and analyze; preparing staff for their evaluation role; and aligning new data collection with existing operations (such as a new item on an existing form, rather than a new form).

It is helpful to demystify the concept of evaluation, Baxter said. Evaluation takes planning and organization, but it can be accomplished if people know what it entails. Baxter closed by urging USDA to invest in formative research to increase the likelihood that strategies and materials will be on target.

GROUP DISCUSSION

Presenter: James Lindenberger

Again, the moderator took written questions from the audience and directed them to the speakers. The topics discussed included

- Availability of existing data for evaluation purposes: Shealy noted that several existing CDC surveys, such as the National Immunization Survey and the National Survey of Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care, include information about breastfeeding and hospital practices. Concerning social media, Bernhardt said that data can be scraped or mined from media streams for forma-

tive research. Using Facebook groups, Twitter hashtags, or other types of key word searches can help identify relevant information to analyze. More sophisticated quantitative tools, such as Radian6 (http://www.radian6.com), can also run aggregations against streams to look for trends and themes as well as to measure the overall reach of a campaign. Saluja pointed out that WIC has data collected about the food package that cover every state and stretch over a period of time. In general, the panelists strongly supported the concept and value of using existing data.

- Specific products or services to support: Baxter said that she felt there is some ambiguity about what “support services” are, although Saluja said that WIC recipients or potential recipients receive an explanation from the outset of enrollment. Saluja said that increasing the number of Baby-Friendly Hospitals would make a difference. Shealy suggested coming up with a product to offer as an incentive in addition to intangible services because society often values “stuff” for babies. The product could be a sling or an outfit for each successful month of breastfeeding—something related to the baby but not necessarily directly to breastfeeding. A drop-in breastfeeding clinic might be another community service to offer. Carothers said that focusing on implementing just a few breastfeeding-friendly practices, as was done with the Colorado Can Do 5! Initiative, is useful. WIC staff also suggest using a referral network to find out where the new mothers are delivering, so peer counselors can help them from the start. Place can be a barrier, Bernhardt noted, which is what makes digital coaching an exciting option. Virtual tools have a huge potential for improving health care. For breastfeeding, having a lactation coach or consultant at the very point of need could be revolutionary.

- Images of breastfeeding: Participants were asked to address the way in which, in some cultures, breastfeeding has a sexual connation. We have to address it head on as part of the necessary formative research, Parvanta said, even if it is an uncomfortable topic. For example, some women will feel comfortable using a breast pump in private but not breastfeeding in front of others. Another example of society’s uneasy relationship with breastfeeding is that a mother cannot post a picture of herself on Facebook breastfeeding (although a petition is circulating to change that policy). “If you want something to be normal, it’s got to be on Facebook,” Parvanta said.

- Distribution of formula by prescription: Saluja noted that recommendations for what to do about formula come up periodically in the WIC program. She said that it is her personal opinion that if a

policy is punitive to the mother, it is wrong, and she also noted the administrative burden it would create if WIC staff had to control distribution in this way. To her, the best approach relies on prenatal education and hospital and community support afterward. She tells her staff that success is when a mother says, “I don’t want formula. I want to breastfeed.”

REFERENCES

Baxter, D. 2011. Defining goals and evaluating success. Presented at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Updating the USDA National Breastfeeding Campaign, Washington, DC, April 26.

Bernhardt, J. M. 2011. Loving Support 2.0: Leveraging new media to increase breastfeeding. Presented at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Updating the USDA National Breastfeeding Campaign, Washington, DC, April 26.

CDC/DNPAO (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity). 2011. State Breastfeeding Coalitions Teleconference: February 8, 2011. http://www.usbreastfeeding.org/Portals/0/Coalitions/Teleconferences/2011-02-08Teleconf-Slides.pdf (accessed August 28, 2011).

CTIA. 2010. U.S. Wireless Quick Facts: Year End Figures. http://www.ctia.org/advocacy/research/index.cfm/AID/10323 (accessed June 17, 2011).

Gross, S. M., A. K. Resnik, J. P. Nanda, C. Cross-Barnet, M. Augustyn, L. Kelly, and D. M. Paige. 2011. Early postpartum: A critical period in setting the path for breastfeeding success. Breastfeeding Medicine. Epub ahead of print.

Kingston, D., C. L. Dennis, and W. Sword. 2007. Exploring breast-feeding self-efficacy. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing 21(3):207–215.

Madden, M. 2010. Older Adults and Social Media. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2010/Pew%20Internet%20-%20Older%20Adults%20and%20Social%20Media.pdf (accessed June 28, 2011).

Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2010. Updated: Change in Internet Access by Age Group, 2000–2010. http://www.pewinternet.org/Infographics/2010/Internet-acess-byage-group-over-time-Update.aspx (accessed June 28, 2011).

Sandman, P. M. 2007. Seesaw Your Way Through Ambivalence. http://www.psandman.com/CIDRAP/CIDRAP8.htm (accessed June 14, 2011).

Smith, A. 2010. Mobile Access 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2010/PIP_Mobile_Access_2010.pdf (accessed June 27, 2011).