Foundations of Reading and Writing

This chapter provides an overview of the components and processes of reading and writing and the practices that develop these skills. This knowledge is derived mainly from research with K-12 students because this population is the main focus of most rigorous research on reading components, difficulties in learning to read, and effective instructional practices. The findings are particularly robust for elementary school students and less developed for middle and high school students due to lack of attention in research to reading and writing development during these years. We also review a small body of research on cognitive aging that compares the reading and writing skills of younger and older adults. From all the collected findings, we distill principles to guide literacy instruction for adolescents and adults who are outside the K-12 education system but need to further develop their literacy.

Caution must be used in generalizing research conducted in K-12 settings to other populations, such as adult literacy students. Precisely what needs to be taught and how will vary depending on an individual’s existing literacy skills; learning goals that require proficiency with particular types of reading and writing; and characteristics of learners that include differences in motivation, neurobiological processes, and cultural, linguistic, and educational backgrounds. Translational research will be needed to apply and adapt the findings to diverse populations of adolescents and adults, as discussed in later chapters.

This chapter is organized into five major parts. Part 1 provides an orienting discussion of the social, cultural, and neurocognitive mechanisms involved in literacy development. Part 2 describes the components and

processes of reading and writing, and research on reading and writing instruction for all students (both typical and atypical learners). We summarize principles for instruction that have sufficient empirical support to warrant inclusion in a comprehensive approach to literacy instruction. Part 3 discusses the neurobiology of reading and writing development and difficulties. Part 4 conveys additional principles for intervening specifically with learners who have difficulties with learning to read and write. In Part 5, we describe what is known about reading and writing processes in older adults and highlight the lack of research on reading and writing across the life span.

Throughout the chapter, we point to promising areas for research and to questions that require further study. We conclude with a summary of the findings, directions for research, and implications for the learners who are the focus of our report: adolescents and adults who need to develop their literacy skills outside K-12 educational settings.1

SOCIAL, CULTURAL, AND NEUROCOGNITIVE

MECHANISMS OF LITERACY DEVELOPMENT

Literacy, or cognition of any kind, cannot be understood fully apart from the contexts in which it develops (e.g., Cobb and Bowers, 1999; Greeno, Smith, and Moore, 1993; Heath, 1983; Lave and Wenger, 1991; Markus and Kitiyama, 2010; Nisbett, 2003; Rogoff and Lave, 1984; Scribner and Cole, 1981; Street, 1984). The development of skilled reading and writing (indeed, learning in general) depends heavily on the contexts and activities in which learning occurs, including the purposes for reading and writing and the activities, texts, and tools that are routinely encountered (Beach, 1995; Heath, 1983; Luria, 1987; Scribner and Cole, 1981; Street, 1984; Vygotsky, 1978, 1986). In this way, reading and writing are similar to other complex cognitive skills and brain functions that are shaped by cultural patterns and stimuli (Markus and Kitayama, 2010; Nisbett, 2003; Nisbett et al., 2001; Park and Huang, 2010; Ross and Wang, 2010). The particular knowledge and skill that develop depend on the literacy practices engaged in, the supports provided for learning, and the demand and value attached to particular forms of literacy in communities and the broader society (Heath, 1983; Scribner and Cole,

__________________

1Other documents have summarized research on the components of reading and writing and instructional practices to develop literacy skills. We refer readers to additional resources for more extensive coverage of this literature (Ehri et al., 2001; Graham, 2006a; Graham and Hebert, 2010; Graham and Perin 2007a, 2007b; Kamil et al., 2008; McCardle, Chhabra, and Kapinus, 2008; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a).

1983; Vygotsky, 1986). Thus, how people use reading and writing differs considerably by context.

As an example, forms and uses of spoken and written language in academic settings differ from those in nonacademic settings, and they also differ among academic disciplines or subjects (Blommaert, Street, and Turner, 2007; Lemke, 1998; Moje, 2007, 2008b; Street, 2003, 2009). Recent work on school subject learning also makes it clear that content and uses of language differ significantly from one subject matter to another (Coffin and Hewings, 2004; Lee and Spratley, 2006; McConachie and Petrosky, 2010). People may develop and use forms of literacy that differ from those needed for new purposes (Alvermann and Xu, 2003; Cowan, 2004; Hicks, 2004; Hull and Schultz, 2001; Leander and Lovvorn, 2006; Mahiri and Sablo, 1996; Moje, 2000a, 2008b; Moll, 1994; Noll, 1998; Reder, 2008). Thus, as depicted in Figure 1-2, a complete understanding of reading and writing development includes in-depth knowledge of the learner (the learners’ knowledge, skills, literacy practices, motivations, and neurocognitive processes) and features of the instructional context that scaffold or impede learning. The context of instruction includes texts, tools, activities, interactions with teachers and peers, and instructor knowledge, beliefs, and skills.

Types of text vary from books to medication instructions to Twitter tweets. Texts have numerous features that in the context of instruction can either facilitate or constrain the learning of literacy skills (Goldman, 1997; Graesser, McNamara, and Louwerse, 2004). Texts that effectively support progress with reading are appropriately challenging and well written. They focus attention on new knowledge and skills related to the particular components of reading that the learner needs to develop. They also support the learner in gaining automaticity and confidence and in applying and generalizing their new skills. To the greatest degree possible, the materials for reading should help to build useful vocabulary and content (e.g., topic, world) knowledge. Effective texts also motivate engagement with instruction and practice partly by developing valued knowledge or relating to the interests of the learner.

Adult learners will have encountered many texts during the course of formal schooling that are poorly written or highly complex (Beck, McKeown, and Gromoll, 1989; Chambliss and Calfee, 1998; Chambliss and Murphy, 2002; Lee and Spratley, 2010). Similarly, the texts of everyday life are not written to scaffold reading or writing skill (Solomon, Van der Kerkhof, and Moje, 2010). Developing readers need to confront challenging texts that engage them with meaningful content, but they also need texts that afford the practicing of the skills they need to develop and systematic

support to stretch beyond existing skills. This support needs to come from a mix of instructional interactions and texts that scaffold the learner in developing and practicing new skills and becoming an independent reader (Lee and Spratley, 2010; Moje, 2009; Solomon, Van der Kerkhof, 2010).

Being literate also requires proficiency with the tools and practices used in society to accomplish valued tasks that require reading and writing (see Box 2-1). For example, digital and online media are used to communicate with diverse others and to produce, find, evaluate, and synthesize knowledge in innovative and creative ways to meet the varied demands of education and work. It is important, therefore, to offer reading and writing

BOX 2-1

Literacy in a Digital Age

Strong reading and writing skills underpin valued aspects of digital literacy in several areas:

• Presentations of ideas

![]() Organizing a complex and compelling argument

Organizing a complex and compelling argument

![]() Adjusting the presentation to the audience

Adjusting the presentation to the audience

![]() Using multiple media and integrating them with text

Using multiple media and integrating them with text

![]() Translating among multiple documents

Translating among multiple documents

![]() Extended text

Extended text

![]() Summary

Summary

![]() Graphics versus text

Graphics versus text

![]() Responding to queries and critiques through revision and written follow-up

Responding to queries and critiques through revision and written follow-up

• Using online resources to search for information and evaluating quality of that information

![]() Using affordances, such as hyperlinks and search engines

Using affordances, such as hyperlinks and search engines

![]() Making effective predictions of likely search results

Making effective predictions of likely search results

![]() Coordinating overlapping ideas expressed in differing language

Coordinating overlapping ideas expressed in differing language

![]() Organizing bodies of information from multiple sources

Organizing bodies of information from multiple sources

![]() Evaluating the quality and warrants of accessed information

Evaluating the quality and warrants of accessed information

• Using basic office software to generate texts and multimedia documents

![]() Writing documents: writing for others

Writing documents: writing for others

![]() Taking notes: writing for oneself

Taking notes: writing for oneself

![]() Preparing displays to support oral presentations

Preparing displays to support oral presentations

![]()

SOURCES: Adapted from National Center on Education and the Economy (1997); Appendix B: Literacy in a Digital Age.

instruction that incorporates the use of print and digital tools as needed for transforming information and knowledge across the varied forms of representation used to communicate in today’s world. These forms include symbols, numeric symbols, icons, static images, moving images, oral representations (available digitally and in other venues), graphs, charts, and tables (Goldman et al., 2003; Kress, 2003). Extensive research has been conducted on youths’ multimodal and digital literacy learning, demonstrating that young people are experimenting with a range of tools and practices that extend beyond those taught in school (see Coiro et al., 2009a, 2009b). Continued research is needed to identify effective instructional methods that incorporate digital technologies (e.g., Coiro, 2003; see Appendix B for detailed discussion of the state of research on digital literacy).

The development of skilled literacy involves extensive participation and practice using component skills of reading and writing for particular purposes (Ford and Forman, 2006; Lave and Wenger, 1991; McConachie et al., 2006; Rogoff, 1990; Scribner and Cole, 1981; Street, 1984; Vygotsky, 1986). Because literacy demands shift over time and across contexts, some individuals may need specific interventions developed to meet these shifting literacy demands. For example, a typical late adolescent or adult must traverse, on a regular basis, workplaces; vocational and postsecondary education; societal, civic, or political contexts; home and family; and new media. Literacy demands also change over time due to global, economic, social, and cultural forces. These realities make it especially important to understand the social and cultural contexts of literacy and to offer instruction that develops literacy skills for meeting social, educational, and workplace demands as well as the learner’s personal needs. The likelihood of transferring a newly learned skill to a new task depends on the similarity between the new task and tasks used for learning (National Research Council, 2005), making it important to design literacy instruction using the literacy activities, tools, and tasks that are valued by society and learners outside the context of instruction. Such instruction also would be expected to enhance learners’ motivation to engage with a literacy task or persist with literacy instruction.

Instruction that connects to knowledge that students already possess and value appears to be motivating (e.g., Au and Mason, 1983; Guthrie et al., 1996; Gutiérrez et al., 1999; Lee, 1993; Moje and Speyer, 2008; Moll and Gonzalez, 1994; Wigfield, Eccles, and Rodriguez, 1998) and thus may be important for supporting the persistence of those who have successfully navigated other life arenas despite not having developed a broader range of literacy skills and practices. Successful literacy instruction for adults and

adolescents should recognize the knowledge and experience brought by mature learners, even when their literacy skills are weak.

Because the motivation to engage in extensive reading and writing practice is so important for the development and integration of component skills, we discuss the topic of motivation more extensively in Chapter 5.

Teacher Knowledge, Skills, and Beliefs

Literacy development, like the learning of any complex task, requires a range of explicit teaching and implicit learning guided by an expert (Ford and Forman, 2006; Forman, Minick, and Stone, 1993; Lave and Wenger, 1991, 1998; Rogoff, 1990, 1993, 1995; Scribner and Cole, 1981; Street, 1984; Vygotsky, 1986; Wertsch, 1991). To be effective, teachers of struggling readers and writers must have significant expertise in both the components of reading and writing, which include spoken language, and how to teach them. The social and emotional tone of the instructional environment also is very important for successful reading and writing development (Hamre and Pianta, 2003). Teachers are more effective when they nurture relationships and develop a positive, dynamic, and emotionally supportive environment for learning that is sensitive to differences in values and experiences that students bring to instruction.

Effective instructors tend to have an informed mental map of where they want their students to end up that they use to guide instructional practices every day. That is, they plan activities using clear objectives with deep understanding of reading and writing processes. Descriptions of effective teachers in the K-12 system stress that they are highly reflective in their teaching, mindful of their instructional choices and how they fit into the larger picture for their students, and able to fluently use and orchestrate a repertoire of effective and adaptive instructional strategies (Block and Pressley, 2002; Butler et al., 2004; Duffy, 2005; Lovett et al., 2008b). Effective teachers use feedback from their own performance to adjust and change instruction, and they are able to transfer and apply knowledge from one domain to another (Duffy, 2005; Israel et al., 2005; Zimmerman, 2000a, 2000b). Effective teachers of reading and writing also have deep knowledge of the English language system and its oral and written structures, as well as the processes involved in acquiring various language abilities (Duke and Carlisle, 2011; Moats, 2004, 2005). Beyond the requisite knowledge and expertise, literacy teachers often need coaching, mentoring, and encouragement to question and evaluate the efficacy of their instruction.

Teacher beliefs can have a profound impact on the opportunities provided during instruction to develop literacy skills. For example, both Green (1983) and Golden (1988) demonstrated how teachers’ instruction changed depending on what the teachers assumed about the literacy abilities of the

students in each group. Students who were identified as reading at lower levels were not asked to think about the texts and interpret them in the same way as those at higher reading levels (see also Cazden, 1985). Being thought of as “successful” or “achieving” or, at the other extreme, “unsuccessful” and “failing” can produce low-literacy learning and even, in some cases, what is identified as disability (McDermott and Varenne, 1995).

As discussed further in Chapter 3, it is well known that the knowledge and expertise of adult literacy instructors are highly variable (Smith and Gillespie, 2007; Tamassia et al., 2007). A large body of research on the efficacy of teacher education and professional development practices for literacy instruction does not exist that could be used as a resource for instructors of adults (McCardle, Chhabra, and Kapinus, 2008; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a; Snow, Griffin, and Burns, 2005). Neither preparation nor selection of instructors in adult literacy education or developmental college courses has been studied much at all and certainly not in terms of ability to apply the practices presented in this chapter. Thus, the issue of instructor preparation for the delivery of effective instructional practices is vital to address in future research.

The field of cognitive neuroscience is opening windows on the brain mechanisms that underlie skilled reading and writing and related difficulties. Much of the research has focused on identifying the neurocircuits (brain pathways) associated with component processes in reading and writing at different stages of typical reading development, and differences in the progression of brain organization for these processes in atypically developing readers. It also has focused mainly on word- and sentence-level reading. More needs to be understood from neurocognitive research about the development of complex comprehension processes. In addition, because different disciplines study different aspects of literacy, much remains to be discovered about how various social, cultural, and instructional factors interact with neurocognitive processes to facilitate or constrain the development of literacy skills.

Brain imaging studies (both structural and functional imaging) have revealed, however, robust differences in brain organization between typically and atypically developing readers (see Chapter 7). It is yet to be determined whether these observed brain differences are the cause or consequence of reading-related problems. It is possible, however, to confirm certain levels of literacy development by observing the brain activity associated with literacy function. More needs to be understood about (1) the genetic, neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and epigenetic factors that control the development of these neurocircuits and (2) the ways in which experiential factors, such as

enriched learning environments, might modulate brain pathways in struggling readers at different ages and in different environments. Research on gene-brain-environment relations has the potential to inform instruction in at least three ways: (1) the development and testing of theories and models of typical and atypical development of reading and writing needed to guide effective teaching and remedial interventions; (2) development of measures that provide more sensitive assessments in specific areas of difficulty to use for instruction and research; and, though less germane to this report, (3) knowledge of neurobiological processes needed for early identification of risk with an eye toward prevention of reading and writing difficulties. The same possibilities apply for writing instruction, although neurobiological research on writing is in the early stages. In subsequent sections, we further describe what is known about the neurobiological mechanisms specific to reading and writing. A key point to keep in mind, however, is that neither the available behavioral data nor neurocognitive data suggest that learners who struggle with reading and writing require a categorically different type of instruction from more typically developing learners. Rather, the instruction may need to be adapted in particular ways to help learners overcome specific reading, writing, and learning difficulties, as discussed later in the chapter.

Reading is the comprehension of language from a written code that represents concepts and communicates information and ideas. It is a complex skill that involves many human capacities that evolved for other purposes and it depends on their development and coordinated use: spoken language, perception (vision, hearing), motor systems, memory, learning, reasoning, problem solving, motivation, interest, and others (Rayner et al., 2001). Reading is closely related to spoken language (National Research Council, 1998) and requires applying what is known about spoken language to deciphering an unfamiliar written code. In fact, the correlation between comprehension of spoken and written language in adults is high, approximately .90 (Braze et al., 2007; Gernsbacher, Varner, and Faust, 1990). Conversely, being less skilled in a spoken language—having limited vocabulary, less familiarity with standard grammar, speaking a different dialect—makes it more difficult to become skilled at reading that language (Craig et al., 2009; Scarborough, 2002). Reading also depends on knowledge of the context and purpose for which the act of reading occurs (Scribner and Cole, 1981; Street, 1984; Vygotsky, 1978).

Although reading and speech are similar, they differ in important ways that have implications for instruction (Biber, 1988; Clark, 1996; Kucer, 2001). Speech fades from memory whereas most types of text are more

permanent, allowing for reanalysis and use of strategies to comprehend complex written structures (Biber and Conrad, 2006). Skilled readers are attuned to the differences between texts and spoken language (e.g., differences in types and frequencies of words, expressions, and grammatical structures) (Biber, 1988; Chafe and Tannen, 1987), and they know the strategies that help them comprehend various kinds of text. Perhaps the most important difference is that people learn to speak (or sign) even when direct instruction is limited or perhaps absent, whereas learning to read almost always requires explicit instruction as well as immersion in written language.

The major components of reading are well documented and include decoding, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Box 2-2 summarizes

BOX 2-2

Principles of Reading Instruction

Becoming an able reader takes a substantial amount of time. Reading is a complex skill, and, like other complex skills, it takes well over 1,000 hours, perhaps several times that, to acquire fully. Instruction consistent with the principles that follow must therefore be implemented and learner engagement supported at the scale required for meaningful gains.

• Use explicit and systematic reading instruction to develop the major components of reading (decoding, fluency vocabulary, comprehension) according to the assessed needs of individual learners. Although each dimension is necessary to proficient reading, adolescents and adults vary in the specific reading instruction they need. For example, some will require comprehensive decoding instruction; others may need less or no decoding instruction. Further research is needed to clarify the forms of explicit instruction that effectively develop component skills for adolescents and adults.

• Combine explicit and systematic instruction with extended reading practice to promote acquisition and transfer of component reading skills. Learning to read involves both explicit teaching and implicit learning. Explicit teaching does not negate the vital importance of incidental and informal learning opportunities or the need for extensive practice using new skills.

• Motivate engagement with the literacy tasks used for instruction and extensive reading practice. Learners, especially adolescents, are more engaged when literacy instruction and practice opportunities are embedded in meaningful learning activities. Opportunities to collaborate during reading also can increase motivation to read, although more needs to be known about how to structure collaborations effectively.

• Develop reading fluency as needed to facilitate efficiency in the reading of words and longer text. Some methods of fluency improvement have been vali-

principles of instruction related to developing each of these components. Although the components are presented separately here for exposition, reading involves an interrelated and interdependent system with reciprocity among the various components, both within reading and between reading and writing.

A substantial body of evidence on children shows that effective reading instruction explicitly and systematically targets each component of reading skill that remains to be developed (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a; Rayner et al., 2001). More extensive evidence for this statement is available for younger than older learners and for word identification and decoding processes than for reading comprehension and

dated in children (e.g., guided repeated reading); these require further research with adolescents and adults.

• Explicitly teach the structure of written language to facilitate decoding and comprehension. Develop awareness of the features of written language at multiple levels (word, sentence, passage). Teach regularity and irregularity of spelling-to-sound mappings, the patterns of English morphology, rules of grammar and syntax, and the structures of various text genres. Again, the specifics of how best to provide this instruction to adolescents and adults requires further research, but the dependence of literacy on knowledge of the structure of written language is clear.

• To develop vocabulary, use a mixture of instructional approaches combined with extensive reading of texts to create “an enriched verbal environment.” High-quality mental representations of words develop through varied and multiple exposures to words in discourse and reading of varied text. Instruction that integrates the teaching of vocabulary with reading comprehension instruction, development of topic and background knowledge, and learning of disciplinary or other valued content are promising approaches to study with adolescents and adults.

• To develop comprehension, teach varied goals and purposes for reading; encourage learners to state their own reading goals, predictions, questions, and reactions to material; encourage extensive reading practice with varied forms of text; teach and model the use of multiple comprehension strategies; teach self-regulation in the monitoring of strategy use. Reading comprehension involves a high level of metacognitive engagement with text. Developing readers often need help to develop the metacognitive components of reading comprehension, such as learning how to identify reading goals, select, implement, and coordinate multiple strategies; monitor and evaluate success of the strategies; and adjust strategies to achieve reading goals. Extensive practice also is needed to develop knowledge of words, text structures, and written syntax that are not identical to spoken language and that are gleaned from extensive experience with various texts.

reading fluency, given that research has focused mainly in these areas. Despite this caveat, this principle of reading instruction is considered to have strong research support (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a). The emphasis of instruction within and across reading components will vary depending on each person’s need for skill development, but skill needs to be attained in all the components. It is possible to design many ways to provide explicit and systematic reading instruction focused on the learner’s needs using methods and formats that will appeal to learners (McCardle, Chhabra, and Kapinus, 2008).

Learning to read involves both explicit teaching and implicit learning. Explicit teaching does not negate the importance of incidental and informal learning opportunities, or the need for extensive practice using new skills. Explicit and systematic reading instruction must be combined with extended experience with reading for varied purposes in order to promote learning and the transfer of reading skills. Thus, it is important to provide forms of reading practice that develop the particular skills that need to be acquired. Learners, especially adolescents, are more engaged when literacy instruction and practice are embedded in meaningful learning activities (e.g., Guthrie and Wigfield, 2000; Guthrie et al., 1999; Schiefele, 1996a, 1996b; Schraw and Lehman, 2001).

Decoding involves the ability to apply knowledge of letter-sound relationships to correctly pronounce printed words. It requires developing phonological awareness, which consists of phonemic awareness (an oral language skill that involves awareness of and ability to manipulate the units of sound, phonemes, in a spoken word) and alphabetic knowledge (knowing that the letters in written words represent the phonemes in spoken words) (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000b; Rayner et al., 2001).

Even highly skilled adult readers must rely on alphabetic knowledge and decoding skills to read unfamiliar words (e.g., “otolaryngology”) (Frost, 1998; Rayner et al., 2001). Word reading also requires being able to recognize sight words that do not follow regular patterns of letter-sound correspondence (e.g., “yacht”). Explicit and systematic phonics instruction to teach correspondences between letters and phonemes has been found to facilitate reading development for children of different ages, abilities, and socioeconomic circumstances (Foorman et al., 1998; McCardle, Chhabra, and Kapinus, 2008; Morris et al., 2010; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a; Torgesen et al., 1999). The evidence is clear that explicit instruction is necessary for most individuals to develop

understanding of written code and its relation to speech (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a; Snow, 2002).

The National Reading Panel, convened at the request of Congress, identified several types of effective systematic phonics programs, among them synthetic phonics (teaching children to convert letters into sounds or phonemes and then blend the sounds to form recognizable words) (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a). The research shows that, although phonological awareness is the oral language building block of reading, teaching phonological awareness for those who need such instruction is most effective when coupled with the use of letters and the learning of letter-sound correspondences as part of phonics instruction.

Many adults with low literacy may experience difficulty with decoding (Baer, Kutner, and Sabatini, 2009; Greenberg, Ehri, and Perin, 1997, 2002; Mellard, Fall, and Woods, 2010; Nanda, Greenberg, and Morris, 2010; Read and Ruyter, 1985; Sabatini et al., 2010). Research on younger populations suggests that instructors may need to be prepared to explicitly and systematically teach all aspects of the word-reading system: letter-sound patterns, high-frequency spelling patterns (oat, at, end, ar), consonant blends (st-, bl-, cr-), vowel combinations (ai, oa, ea), affixes (pre-, sub-, -ing, -ly), and irregular high-frequency word instruction (sight words that do not follow regular spelling patterns). For those adults who need to develop their word-reading skills, it may be important to teach “word attack” strategies with particular attention to challenges posed by multisyllabic words and variable vowel pronunciations. Effective word attack strategies for all readers include phonological decoding and blending, word identification by analogy, peeling off prefixes and suffixes, and facility with variable vowel pronunciations (for information about these word-reading strategies and how to use them, see Lovett et al., 1994, 2000; Lovett, Lacerenza, and Borden, 2000). Even after adult learners have mastered decoding, they may need substantial practice to become able to decode words easily, freeing up limited attentional capacity for other reading processes, like comprehension (see discussion of fluency below).

Vocabulary knowledge is a primary predictor of reading success (Baumann, Kame’enui, and Ash, 2003). It is associated with word identification skills at the end of first grade (Sénéchal and Cornell, 1993) and reading comprehension in eleventh grade (Cunningham and Stanovich, 1998; Nagy, 2007). In fact, for those who have acquired basic decoding skills, the aspect of lexical (word) processing that has the greatest impact on reading is vocabulary knowledge and, more specifically, the depth, breadth, and

flexibility of knowledge about words (Beck and McKeown, 1986; Perfetti, 2007). Vocabulary also tends to grow with reading experience. As readers progress, lexical analysis (i.e., morphological awareness allowing the recognition of derived words, e.g., decide→decision, decisive, deciding) becomes increasingly important for comprehending complex and unfamiliar words and concepts (Adams, 1990; Nagy and Anderson, 1984; Nagy and Scott, 2000). Specialized vocabulary is important to develop for comprehending texts in different subject-matter areas (Koedinger and Nathan, 2004).

The National Reading Panel (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a) concluded that explicit vocabulary instruction is associated with gains in reading comprehension. Other research reviews have been less definitive, and thus some researchers consider the evidence to be mixed (Kamil et al., 2008; Pressley, Disney, and Anderson, 2007). Differences in findings across studies may be due partly to variations in the approaches and how they were implemented, the lack of direct measures of vocabulary growth in some studies, and the use of measures that fail to assess all dimensions of word knowledge or reading comprehension. These issues should be addressed in future research with adult and adolescent populations.

Research on literacy instruction for children suggests that selecting words from the curriculum and teaching their meanings prior to reading a text help to ensure that vocabulary items are in the spoken language of the reader prior to encountering the words in print (Beck, McKeown, and Kucan, 2002; McKeown and Beck, 1988; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a). For less skilled readers, explicit instruction, combined with discussion and elaboration activities that encourage using the words to be learned, can improve vocabulary and facilitate better reading comprehension (Curtis and Longo, 2001; Foorman et al., 2003; Klinger and Vaughn, 1999; Stahl and Fairbanks, 1986). Beck and colleagues (Beck and McKeown 2007; McKeown and Beck, 1988) articulated principles for developing a teacher’s ability to deliver effective vocabulary instruction: (a) introduce vocabulary through connected language (discussion, elaboration activities) instead of only dictionary definitions, (b) provide multiple opportunities to interact with new words and word meanings in a variety of engaging contexts, and (c) use activities that engage learners in deep and reflective processing of word meanings. In addition, repeated exposure to words in multiple contexts and domains enhances vocabulary learning (Kamil et al., 2008; Nagy and Scott, 2000) and provides “an enriched verbal environment” (Beck, McKeown, and Kucan, 2002) for vocabulary growth. Findings that show no effect for vocabulary instruction have tended to look at more impoverished forms of instruction.

Having rich knowledge of words (i.e., high-quality lexical representa-

tions) allows for rapid and reliable retrieval of word meanings with profound consequences for both word- and text-reading proficiency (Perfetti, 1992, 2007). Reading is supported by knowing not only the definition of the words being read but also how the words are used, their different forms (e.g., anxious→anxiety), and what they connote in different situations. Findings from research on children indicate that effective approaches to vocabulary instruction will consist of strategies that build high-quality lexical representations and develop metalinguistic awareness (Nagy, 2007). These strategies include teaching not only word meanings but also multiple meanings of words and varied word forms and origins, as well as providing ample opportunities to encounter and use the words in varied contexts. As more text becomes available in electronic form, it also may be possible to develop more tools that provide text-embedded “just-in-time” vocabulary support that developing readers can call on when their reading is impeded by lack of word or lexical knowledge.

Embedding vocabulary instruction in reading comprehension activities is another method of developing high-quality lexical representations (Perfetti, 1992, 2007). This approach involves reading new texts that develop vocabulary, topic, and domain knowledge. Readers acquire new words, phrases, and concepts that appear more often in text than in speech and that would therefore lie outside most learners’ experience with spoken language (Kamil et al., 2008). For example, because academic texts (e.g., those in science or history) include specialized vocabulary that is not part of everyday spoken language (Beck, McKeown, and Kucan, 2002; Kamil et al., 2008), the teaching of content needs to be integrated with explicit teaching of words and phrases used in a discipline (Moje and Speyer, 2008). Such approaches warrant study with those outside K-12 because adolescents and adults may need to develop academic or other specialized vocabulary and content knowledge for education, work, or other purposes.

Overall, findings suggest a range of vocabulary activities that may be useful in adult literacy instruction, but, at present, research on adults is extremely limited.

Reading fluency is the ability to read with speed and accuracy (Klauda and Guthrie, 2008; Kuhn and Stahl, 2003; Miller and Schwanenflugel, 2006). Developing fluency is important because the human mind is limited in its capacity to carry out many cognitive processes at once (Logan, 2004). When word and sentence reading becomes automatic, readers can concentrate more fully on creating meaning from the text (Graesser, 2007; Perfetti, 2007; Rapp et al., 2007; van den Broek et al., 2009). Experiments

with young children show that fluency instruction can lead to significant gains in both fluency and comprehension (Chard, Vaughn, and Tyler, 2002; Klauda and Guthrie, 2008; Kuhn and Stahl, 2003; Therrien, 2004; Therrien and Hughes, 2008).

The relation between fluency and comprehension is not fully understood, however, and it is more complex and bidirectional than previously thought (Meyer and Felton, 1999; Wolf and Katzir-Cohen, 2001). Comprehension appears to affect fluency as well as the reverse (Collins and Levy, 2008; Johnston, Barnes, and Desrochers, 2008; Klauda and Guthrie, 2008). Moreover, although some studies show that fluency instruction improves comprehension, other studies do not (Fleisher, Jenkins, and Pany, 1979; Grant and Standing, 1989; Oakhill, Cain, and Bryant, 2003). There are at least two possible reasons for the mixed findings to address in future research. Studies have demonstrated that there are different dimensions of reading fluency (at the level of words, phrases, sentences, and passages), and all should be considered in measuring or facilitating reading fluency. In addition, the best ways to conceptualize and measure text comprehension have yet to be identified and used consistently across research studies.

Guided repeated reading has generally led to moderate increases in fluency, accuracy, and sometimes comprehension for both good and poor readers (Kuhn and Stahl, 2003; Kuhn et al., 2006; Vadasy and Sanders, 2008). In guided repeated reading, the learner receives feedback and is supported in identifying and correcting mistakes. A critical unanswered question is whether certain types of text are more effective than others for guided repeated reading interventions (Kuhn and Stahl, 2003; Vadasy and Sanders, 2008).

Repeated reading of a text without guidance, though a popular instructional method believed to improve fluency, has not been reliably demonstrated to be effective, even with young children in K-3 classrooms (Carlisle and Rice, 2002; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a; Stahl, 2004). At least one recent review suggests that there is not enough rigorous evidence to warrant unguided repeated reading for students with or at risk for learning disabilities (Chard et al., 2009). A well-designed controlled evaluation with high school students with reading disabilities also failed to find support for repeated reading effects on reading comprehension (Wexler et al., 2010).

Fluency has been difficult to change for adolescent and adult readers (Fletcher et al., 2007; Wexler et al., 2010). One possible reason is that older struggling readers lack sufficient reading practice and experience. Another possible reason is that instruction must focus on developing not only the reader’s ability to decode or recognize individual words but to quickly process larger units of texts (e.g., sentences and paragraphs). In the future, fluent reading needs to be studied at the word level, syntactic level, and

passage level. Fluency at each of these levels has been found to contribute to growth in reading comprehension for fifth graders (Klauda and Guthrie, 2008; see also Kuhn and Stahl, 2003; Young and Bowers, 1995). To encourage the practice needed for fluency, it is important to develop procedures and text types that will engage older developing readers.

Components and Processes

Although they differ in detail, theories of reading comprehension share many assumptions about the cognitive processes involved (Cromley and Azevedo, 2007; Gernsbacher, Varner, and Faust, 1990; Graesser, Singer, and Trabasso, 1994; Kintsch, 1998; Trabasso, Secco, and van den Broek, 1984; van den Broek, Rapp, and Kendeou, 2005; Zwaan and Singer, 2003). First, comprehension requires adequate and sustained attention. In complex cognitive acts, such as reading comprehension, attention cannot simultaneously be focused in an unlimited number of ways. As mentioned earlier, facile readers develop fluent and relatively automatic decoding that allows allocating more attention to the information gleaned from words and phrases and creating coherent meaning from text (Ericsson and Kintsch, 1994; Kintsch and van Dijk, 1978; O’Brien et al., 1998). Concentration also must be sustained so that memories of previous sentences and pages do not fade before the next text is read, and this is less possible when a decoding problem diverts attention from prior content.

Second, comprehension requires the reader to interpret and integrate information from various sources (the sentence being read, the prior sentence, prior text, background knowledge, and extraneous information) (Goldman, Graesser, and van den Broek, 1999; Graesser, Gernsbacher, and Goldman, 2003; Graesser, Singer, and Trabasso, 1994; Kintsch, 1998; Kintsch and van Dijk, 1978; McCardle, Chhabra, and Kapinus, 2008; Rapp et al., 2007; Rumelhart, 1994; Snow, 2002; Trabasso and van den Broek, 1985; van den Broek, Rapp, and Kendeou, 2005). Comprehension depends heavily on background knowledge for understanding how elements in a text relate to one another to create a broader meaning (McNamara et al., 1996; O’Reilly and McNamara, 2007). Nontextual information that accompanies the text (figures or multimedia) must also be integrated to support deeper comprehension (Hegarty and Just, 1993; Lowe and Schnotz, 2007; Mayer, 2009; Rouet, 2006). Such information distracts the unskilled reader. With practice, however, strategic processes for remembering, interpreting, and integrating information become less effortful.

Third, each reader has at least an implicit standard of coherence used while reading to determine whether the type and level of comprehension

aimed for is being achieved (Kintsch and Vipond, 1979; van den Broek, Risden, and Husebye-Hartman, 1995). That is, readers must decide how hard to try and how long to persist in reading a text. Effective readers keep working to better understand text until certain requirements are met. The standard varies depending on such factors as the person’s reading goal, interest, and fatigue. A facile reader strives for an overall understanding of text that is rich with meaning and complete and is highly effective in adjusting the allocation of effort for particular purposes (Duggan and Payne, 2009; Kaakinen and Hyönä, 2007, 2008, 2010; Kaakinen, Hyönä, and Keenan, 2003; Kintsch, 1994; Linderholm and van den Broek, 2002; Reader and Payne, 2007; Stine-Morrow et al., 2004, 2006; Stine-Morrow, Miller, and Hertzog, 2006; Therriault, Rinck, and Zwaan, 2006; Zwaan, Magliano, and Graesser, 1995). A rich and complete understanding involves making inferences, retrieving prior knowledge, and connecting components of text that may not be contiguous on the page. It also requires attending to semantic connections given in the text. Two types of coherence relations—referential and causal—are central to many types of texts (Britton and Gulgoz, 1991; McNamara et al., 1996; van den Broek et al., 2001), but readers also use other relations in text (spatial, temporal, logical, intentional) to create meaning (Graesser and Forsyth, in press; van den Broek et al., 2001; Zwaan and Radvansky, 1998).

Although theories of reading comprehension overlap in many respects, they vary in the number and types of components emphasized and how these components interact (Graesser and McNamara, 2010). The Direct and Inferential Mediation Model (DIME; Cromley and Azevedo, 2007), for example, focuses on five general factors that affect comprehension and that every comprehension theory includes in some form: (1) background knowledge, (2) word-reading, (3) vocabulary, (4) strategies, and (5) inference procedures. These factors accounted for a substantial 66 percent of the variation in reading comprehension in a study of 175 ninth graders.

Different types of text place different demands on the reader, and skilled readers adjust their reading according to what is being read and why (McCrudden and Schraw, 2007; Pressley, 2000; Rouet, 2006). Thus, other approaches to comprehension research focus on how variations in text (genre, style, structure, purpose, content, complexity) influence how people read text and develop knowledge of text structures. Box 2-3 presents an example of one text-based model of reading comprehension.

Reading Comprehension Instruction

Although current theories and models of comprehension are useful for guiding instruction, they require further development. A more systematic and integrated approach to reading comprehension research is needed to

BOX 2-3

A Text-Based Model of Reading Comprehension

Proposed by Graesser and McNamara (2010), the multilevel text model, which extends earlier research by Garrod and Pickering (2004), Kintsch (1998), and Zwaan and Radvansky (1998), identifies seven main components of text processing that affect comprehension: lexical decoding, word knowledge, syntax, genre and rhetorical structure, textbase, situation model, and pragmatic communication (see also Graesser and McNamara, 2011; Kintsch, 1998; Perfetti, 1999).

• Lexical decoding, word knowledge, and syntax components refer to word-and sentence-reading skills.

• Knowledge of genres (narration, exposition, persuasion, description) and global text structures also aids comprehension. A proficient reader processes the rhetorical composition used in various genre and discourse functions of text segments (sections, paragraphs, sentences) and their relation to the overall organization of the text (citation). (Examples of rhetorical structures used to compose expository texts are cause + effect, claim + evidence, problem + solution, and compare + contrast.)

• Full processing of the textbase (propositions explicitly stated in the text) is needed for accurate comprehension. For example, a ubiquitous problem among unskilled readers is the tendency to minimally process propositions, rely too much on what they “know” about the topic from their own experience, and miss parts of the text that do not match their experience.

• Situation model refers to creating larger representations of meaning, derived both from propositions stated explicitly (the textbase) and a large number of inferences that must be filled in using world knowledge.

• Pragmatics refers to the communication goals of spoken and written language. Proficient, goal-directed readers search, select, and extract relevant information from text, further evaluate what they read for relevance to their goals, and use relevance to monitor their attention while reading. People best comprehend and learn from text when the pragmatic function of the text matches the readers’ goals.

develop instruction that can be evaluated using rigorous experimental research designs.

The report of the National Reading Panel (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a) is a main source of experimental evidence on instruction that contributes to developing comprehension. More recent research also has sought a better understanding of the components of instruction that improve comprehension among students at different ages and with different levels of reading skills (e.g., Berkeley, Mastropieri, and Scruggs, 2011; Edmonds et al., 2009). We draw on all of these sources of information in discussing what is known about effective comprehension instruction.

The National Reading Panel analyzed the results of 203 different studies of reading comprehension instruction with students in grades 4 and above and identified eight instructional procedures that had a positive effect on reading comprehension. In this analysis and in more recent research, comprehension strategy instruction emerges as one of the most effective interventions (Forness et al., 1997; Gersten et al., 2001; Kamil, 2004; Kamil et al., 2008; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a). Similarly, an influential meta-analysis of comprehension interventions, including for students with learning disabilities (Swanson, 1999), supports the efficacy of strategy instruction models.

Several core findings have emerged from the research on comprehension strategy instruction. First, different texts and challenges to comprehension require the use of different strategies. Effective comprehension requires understanding all of the strategies, when and why to select particular strategies, how to monitor their success, and how to adjust strategies as needed to achieve the reading goal (Mason, 2004; Sinatra, Brown, and Reynolds, 2002; Vaughn, Klinger, and Hughes, 2000). The greatest benefits occur when students learn to flexibly use and coordinate multiple comprehension strategies (Kamil et al., 2008; Lave, 1988; Vaughn, Klinger, and Hughes, 2000).

Comprehensive strategy instruction is more effective if students are taught all of the preskills and knowledge they will need to use the strategies effectively. The 2008 practice guide on adolescent literacy published by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences cautions that, to be effective, explicit strategy instruction must provide sufficient supports (Kamil et al., 2008). Among those supports are explicit instruction on different aspects of text structure (Williams et al., 2005, 2007), familiarity with different text genres, and recognition of the different conventions authors use to convey meaning. For example, less skilled readers often have limited knowledge of narrative or expository text structures and do not rely on structural differences in text to assist their reading (Meyer, Brandt, and Bluth, 1980; Rapp et al., 2007; Williams, 2006). As more text is available in electronic forms and as display devices become more ubiquitous, it will be possible to embed prompts and other “pop-up” preskill supports in texts to help scaffold the comprehension process.

Strategy instruction depends heavily on opportunities to draw from existing knowledge and build new knowledge (Alexander and Judy, 1989; McKeown, Beck, and Blake, 2009; Moje and Speyer, 2008; Moje et al., 2010). World, topic, and domain knowledge are important to the effective use of strategies (Alexander and Judy, 1989; Moje and Speyer, 2008). Learners with limited or fragmented knowledge of a subject typically apply general and relatively inefficient strategies in an inflexible manner (Alexander, 1997; Alexander, Graham, and Harris, 1998). As their knowl-

edge expands and becomes better integrated, learners begin to use strategies more efficiently and flexibly. The value of some strategies declines with more knowledge about the content (rereading specific sections of text), whereas the value of others increases (e.g., mentally summarizing or elaborating main ideas that involve deeper processing of text).

Strategy instruction seems most effective when it incorporates ample opportunities for practice (Kamil et al., 2008; Pressley and Wharton-McDonald, 1997; Pressley et al., 1989a, 1989b). Incorporation of attributional retraining (Berkeley et al., 2011; Borkowski, Weyhing, and Carr, 1988; Schunk and Rice, 1992) and training to improve metacognitive processes (Malone and Mastropieri, 1992) also appear to enhance the effectiveness of strategy instruction. Understanding of text improves if readers are asked to state reading goals, predictions, questions, and reactions to the material that is read (Kamil et al., 2008; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000a; Palincsar and Brown, 1984). These practices may be effective because they engage readers in more active processing of the content or develop the metacognitive and self-regulatory skills needed for reading comprehension, which requires substantial metacognitive capability.

Knowledge of the various ways to support comprehension remains to be developed in several ways. It is known that the development of comprehension requires having extensive opportunities to practice skills with materials and engagement with varied forms of text (Rayner et al., 2001; Snow, 2002). A question for research is the degree to which explicit instruction to develop knowledge of text components facilitates comprehension. Often the components of text described in text-based models of reading (e.g., see Box 2-3) are learned mainly from practice with reading varied texts instead of from explicit teaching (Hacker, Dunlosky, and Graesser, 2009). Adults who lack reading comprehension skills developed through years of accumulated experience with reading especially might benefit from explicit instruction to develop awareness of text components that often happens implicitly.

Research on the development of literacy and language in the context of learning domain content for broader learning goals (e.g., Lee, 1993; McKeown and Beck, 1994; Moje, 1995, 1996, 1997) is promising to pursue with adolescents and adults needing both to improve their literacy skills and to develop background and specialized knowledge. One of these approaches, disciplinary literacy, seeks to make explicit the different reading and writing demands and conventions of the disciplinary domains, given that the disciplines use particular ways of reading and writing to solve real-world problems (Bain, 2000; Coffin, 2000; Hynd-Shanahan, Holschuh, and Hubbard, 2004; McConachie and Petrosky, 2010; Moje, 2007, 2008a;

Shanahan and Shanahan, 2008; Wineburg, 1991, 1998). This emerging body of research points to several important findings.

First, rich discussion about text may increase both literacy outcomes and understanding of content (Applebee et al., 2003). Similarly, instruction specific to the writing valued in the disciplines can increase both the quality of written text and the disciplinary content learned (e.g., Akkus et al., 2007; Coffin, 2006; Hohenshell and Hand, 2006; Moje et al., 2004b). Second, readers of a range of ages taught to read using texts and language practices valued in the disciplines show enhanced understanding of the content and ability to engage critically with the content (Bain, 2005, 2006; Palincsar and Magnusson, 2001). Third, close study of the linguistic structures of textbooks and related texts appears to enhance students’ understanding of the content (e.g., Schleppegrell and Achugar, 2003; Schleppegrell, Achugar, and Oteíza, 2004). Research is needed to evaluate the approaches more fully with samples that include diverse populations of adolescents and adults who need to develop their reading skills.

Although experimental research has focused mainly on the use of effective reading strategies, research is needed to determine how best to combine strategy instruction with other practices that may further facilitate the development of comprehension. McKeown, Beck, and Blake (2009) demonstrated, for example, that focusing students’ attention on the content of the text through the use of open-ended questions was more effective in developing comprehension than the same amount of time invested in strategy instruction. An important direction for research with adolescents and adults is to identify the best methods of integrating strategy instruction with the development of content knowledge, vocabulary, and other aspects of language competence for reading comprehension to meet the assessed needs of the learner.

Findings also suggest that the critical analysis of text, such as asking readers to consider the author’s purposes in writing the text; the historical, social, or other context in which the text was produced; and multiple ways of reading or making sense of the text may encourage deeper understanding of text (Bain, 2005; Greenleaf et al., 2001; Guthrie et al., 1999; Hand, Wallace, and Yang, 2004; McKeown and Beck, 1994; Palinscar and Magnusson, 2001; Paxton, 1997, Romance and Vitale, 1992). Introducing and explicitly comparing features of texts and literacy practices across languages and cultures also may be helpful to some readers (Au and Mason, 1983; Heath, 1983; Lee, 1993). A recent meta-analysis (Murphy et al., 2009) indicates that critical thinking, reasoning, and argumentation about text all warrant more systematic attention to determine the instructional practices that are effective for developing comprehension skills.

In general, more needs to be known about individual differences in comprehension, which is a major objective of the Reading for Understand-

ing initiative of the Institute of Education Sciences launched in 2010. Individuals may possess certain combinations of proficiencies and weaknesses in comprehension that are important to understand and to measure to guide instructional practice.

The range of skill components to be practiced and the amount of practice required are substantial for the developing reader. At the same time, available evidence suggests that adult learners do not persist in formal programs for anywhere near the amount of time needed to accomplish all of the needed preskill training and reading practice (Miller, Esposito, and McCardle, 2011; Tamassia et al., 2007). Consequently, it is important to better understand how to motivate longer and deeper engagement with reading practice by adult learners.

It is likely that selecting texts that are compatible with learning goals will result in more persistence at deep understanding. Self-reported motivation to perform certain reading tasks in the classroom predicts moderately well students’ performance on the reading tasks and reading achievement scores (Guthrie and Wigfield, 2005; Guthrie, Taboada, and Coddington, 2007; Schiefele, Krapp, and Winteler, 1992). In general, it is well established that academic performance improves when motivation and engagement are nurtured and constructive attributions and beliefs about effort and achievement are reinforced. Opportunities to collaborate during reading also can increase motivation to read (Guthrie, 2004; Guthrie and Wigfield, 2000; Slavin, 1995, 1999; Wigfield et al., 2008) although more needs to be known about how to structure collaborations effectively. We highlight key findings of that research in Chapter 5.

Writing is the creation of texts for others (and sometimes for the writer) to read. People use many types of writing for a variety of purposes that include recording and tabulating, persuading, learning, communicating, entertaining, self-expression, and reflection. Proficiency in writing for one purpose does not necessarily generalize to writing for other purposes (Osborn Popp et al., 2003; Purves, 1992; Schultz and Fecho, 2000). In today’s world, proficiency requires developing skills in both traditional forms of writing and newer electronic and digital modes (see Appendix B). In the last three decades, much more has become known about the components and processes of writing and effective writing instruction. As with reading, most of this research comes from K-12 settings.

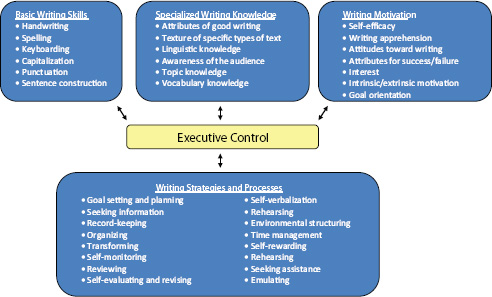

FIGURE 2-1 Model of the components and processes of writing.

Components and Processes of Writing

Figure 2-1 shows the component skills and processes of writing. As the figure shows, the writer manages and orchestrates the application of a variety of basic writing skills, specialized writing knowledge, writing strategies, and motivational processes when writing. The application of these skills and processes is interrelated and varies depending on the task and purpose of the writer.

Basic Writing Skills

Basic writing skills include planning, evaluating, and revising of discourses; sentence construction (including selecting the right words and syntactic structure to convey the intended meaning); and text transcription skills (spelling, handwriting, keyboarding, capitalization, and punctuation; Graham, 2006b).

Sentence construction involves selecting the right words and syntactic structures for transforming ideas into text that conveys the intended meaning. Skilled writers can deftly produce a variety of different types of sentences for effective communication. Facility with writing does not always mean constructing more complex sentences (Houck and Billingsley, 1989). Sentence complexity varies as a function of several factors, such as genre (Hunt, 1965; Scott, 1999; Scott and Windsor, 2000). Yet better writ-

ers produce more complex sentences than less skilled writers (Hunt, 1965; Raiser, 1981), and teaching developing and struggling writers how to craft more complex sentences improves not only their sentence writing skills, but also the quality of their texts (Graham and Perin, 2007b; Hillocks, 1986).

For those developing or struggling writers who need to develop spelling, handwriting, or keyboarding skills, instruction in these areas improves these skills and enhances other aspects of writing performance (Berninger et al., 1998; Christensen, 2005; Graham, Harris, and Fink, 2000; Graham, Harris, and Fink-Chorzempa, 2002).

Specialized Writing Knowledge

Writing also depends on specialized knowledge beyond the level of specific sentences: knowledge of the audience (Wong, Wong, and Blenkinsop, 1989), attributes of good writing, characteristics of specific genres and how to use these elements to construct text (Englert and Thomas, 1987; Graham and Harris, 2003), linguistic knowledge (e.g., of words and of text structures that differ from those of speech) (Donovan and Smolkin, 2006; Groff, 1978), topic knowledge (Mosenthal, 1996; Mosenthal et al., 1985; Voss, Vesonder, and Spilich, 1980), and the purposes of writing (Saddler and Graham, 2007). In general, skilled writers possess a more sophisticated conceptualization of writing than less skilled writers (Graham, Schwartz, and MacArthur, 1993). The developing writer’s knowledge about writing also predicts individual differences in writing performance (Bonk et al., 1990; Olinghouse and Graham, 2009). A small body of evidence shows that efforts to increase developing and struggling writers’ knowledge about writing, especially knowledge of text structure, improve the writing performance of school-age students (Fitzgerald and Markham, 1987; Fitzgerald and Teasley, 1986; Holliway and McCutchen, 2004) and college students (Traxler and Gernsbacher, 1993; Wallace et al., 1996).

Writing Strategies and Self-Regulation

Writing depends on the use of strategies and knowledge that must be coordinated and regulated to accomplish the writer’s goal (Graham, 2006a; Hayes and Flower, 1980; Kellogg, 1993b; Zimmerman and Reisemberg, 1997). These include goal setting and planning (e.g., establishing rhetorical goals and tactics to achieve them), seeking information (e.g., gathering information pertinent to the writing topic), record-keeping (e.g., making notes), organizing (e.g., ordering notes or text), transforming (e.g., visualizing a character to facilitate written description), self-monitoring (e.g., checking to see if writing goals are met), reviewing records (e.g., reviewing notes or the text produced so far), self-evaluating (e.g., assessing the

quality of text or proposed plans), revising (e.g., modifying text or plans for writing), self-verbalizing (e.g., saying dialogue aloud while writing or personal articulations about what needs to be done), rehearsing (e.g., trying out a scene before writing it), environmental structuring (e.g., finding a quiet place to write), time planning (e.g., estimating and budgeting time for writing), self-rewarding (e.g., going to a movie as a reward for completing a writing task), seeking social assistance (e.g., asking another person to edit the paper), and emulating the writing style of a more gifted author (Scardamalia and Bereiter, 1985; Zimmerman and Riesemberg, 1997).

As in reading, the strategies must be applied intelligently with an understanding of when and why to use a particular approach (Breetvelt, Van den Bergh, and Rijlaarsdam, 1994, 1996; Van den Bergh and Rijlaarsdam, 1996). For example, in a study of high school students’ use of 11 writing strategies, use of strategy at the most opportune time was a strong predictor of the quality of writing. Skilled writing especially requires planning and revising (Graham and Harris, 2000a; Hayes and Flower, 1980; Zimmerman and Reisemberg, 1997). For example, children and adolescents spend very little time planning and revising, whereas more accomplished writers, such as college students, spend about 50 percent of writing time planning and revising text (Graham, 2006b; Kellogg, 1987, 1993a). Explicit teaching of strategies for planning and revising has a strong and positive effect on the writing of both developing and struggling writers (Graham and Perin, 2007b; Rogers and Graham, 2008). Similar results have been found for adults needing to develop their writing skills (MacArthur and Lembo, 2009).

Writing Motivation

Despite its importance, motivation is one of the least frequently studied aspects of writing. In this small literature, the most commonly studied topics are attitudes about writing, including self-efficacy, interest, and writing apprehension, and goals for writing (Brunning and Horn, 2000; Graham, Berninger, and Fan, 2007; Hidi and Boscolo, 2006; Madigan, Linton, and Johnston, 1996; Pajares, 2003).

Attitudes toward writing predict writing achievement (Knudson, 1995; see also Graham, Berninger, and Fan, 2007), and poor writers have less positive attitudes about writing than good writers (Graham, Schwartz, and MacArthur, 1993). Thus, it is important to establish positive attitudes about writing. Attitudes may be influenced by self-efficacy or belief in one’s ability to write well. Self-efficacy predicts writing performance (Albin, Benton, and Khramtsova, 1996; Knudson, 1995; Madigan, Linton, and Johnston, 1996; Pajares, 2003), and, with only some exceptions (Graham, Schwartz, and MacArthur, 1993), weaker writers have a lower sense of

self-efficacy than stronger writers (Shell et al., 1995; Vrugt, Oort, and Zeeberg, 2002).

Self-efficacy is especially important to the social-cognitive model of writing proposed by Zimmerman and Reisemberg (1997; Zimmerman, 1989), which specifies that writing is a goal-driven, self-initiated, and self-sustained activity that involves both cognition and affect. The model, which is derived from empirical research and professional writers’ descriptions of how they compose, specifies the self-initiated thoughts, feelings, and actions that writers use to attain various writing goals. Related findings show that the perceived level of success (or failure) in the self-regulated use of writing strategies enhances (or diminishes) self-efficacy and affects intrinsic motivation for writing, further use of self-regulatory processes during writing, and attainment of writing skills and goals. Goals are important because they prompt marshaling the resources, effort, and persistence needed for proficient writing (Locke et al., 1981). Setting goals is especially important when engaging in a complex and demanding task such as writing, which requires a high level of cognitive effort (Kellogg, 1986, 1987, 1993a). As noted earlier in this chapter, arranging writing tasks so that they are consistent with learners’ goals is especially helpful.

Linguistic and Cognitive Foundations of Writing

Writing systems developed as a way to record speech in more permanent form for such purposes as extending memory or creating legal records (Nissen, Damerow, and Englund, 1993). Thus, it is not surprising that facility with reading and writing draws on many of the same skills and that these overlap with those of spoken language (Nelson and Calfee, 1998; Tierney and Shanahan, 1991). These include knowledge of alphabetics (phonemic and phonological awareness), English spelling patterns, vocabulary and etymology (word origins), morphological structures, syntax and sentence structures, and text and discourse structures.

Skilled writing also involves cognitive capacities that evolved earlier and separate from literacy (Graham and Weintraub, 1996; McCutchen, 2006; Shanahan, 2006). Key among these is working memory (Hayes, 1996; Swanson and Berninger, 1996), which is needed, for example, to create interconnections that increase the coherence of text. Writing also requires use of executive functions to coordinate and flexibly use a variety of writing strategies (Graham, 2006b) and more generally purposefully activate, orchestrate, monitor, evaluate, and adapt writing to achieve communication goals (Graham, Harris, and Olinghouse, 2007).

A number of principles for writing instruction are supported by research (see Box 2-4), although the body of research is smaller than for reading. This research includes a focus on both narrative and expository writing (Graham and Perin, 2007a).

A key principle from this research is that explicit and systematic instruction is effective in teaching the strategies, skills, and knowledge needed to be a proficient writer. Almost all the effective writing practices identified in three meta-analyses of experiments and quasi-experiments (grades 4-12, Graham and Perin, 2007a; grades 3 through college, Hillocks, 1986; and grades 1-12, Rogers and Graham, 2008) involved explicit instruction. These practices proved effective with a range of writers, from beginners to college students, as well as with those who experienced difficulty in learning to write. What should be taught, however, depends on the writer’s developmental level, the skills the writer needs to develop for particular purposes, and the writing task.

A comprehensive meta-analysis of experiments and quasi-experiments by Graham and Perin (2007a) conducted with students in grades 4-12 supports use of the practices in Box 2-5. This meta-analysis also shows that learners can benefit from the process approach to writing instruction (Graves, 1983), although the approach produces smaller average effects than methods that involve systematic instruction of writing strategies (Graham and Perin, 2007a). In another recent meta-analysis, the process approach was not effective for students who were weaker writers (Sandmel and Graham, in press). The process approach is a “workshop” method of teaching that stresses extended writing opportunities, writing for authentic

BOX 2-4

Principles of Writing Instruction

• Explicitly and systematically teach the strategies, skills, and knowledge needed to be a proficient writer.

• Combine explicit and systematic instruction with extended experience with writing for a purpose, with consideration of message, audience, and genre.

• Explicitly teach foundational writing skills to the point of automaticity.

• Model writing strategies and teach how to regulate strategy use (e.g., how to select, implement, and coordinate writing strategies; how to monitor, evaluate, and adjust strategies to achieve writing goals).

• Develop an integrated system of skills by using instructional approaches that capitalize on and make explicit the relations between reading and writing.

• Structure instructional environments and interactions to motivate writing practice and persistence in learning new forms of writing.

BOX 2-5

Effective Practices in Writing Instruction

• Strategy instruction for planning, revising, and/or editing compositions.

• Summarizing reading passages in writing.

• Peer assistance in planning, drafting, and revising compositions.

• Setting clear, specific goals for purposes or characteristics of the writing.

• Using word processing regularly.

• Sentence-combining instruction (instruction in combining short sentences into more complex sentences, usually including exercises and application to real writing).

• Process approach to writing with professional development.

• Inquiry approach (including clear goals, analysis of data, using specified strategies, and applying the analysis to writing).

• Prewriting activities (teaching students activities to generate content prior to writing).

• Analyzing models of good writing (discussing the features of good essays and learning to imitate those features).

![]()

NOTE: The practices are listed in descending order by effect size.

SOURCE: Adapted from Graham and Perin (2007a).

audiences, personalized instruction, and cycles of writing. It relies mainly on incidental and informal methods of instruction. The approach is most effective when teachers are taught how to implement it (Graham and Perin, 2007a). It is possible that process approaches would be more effective if they incorporated explicit and systematic instruction to develop essential knowledge, strategies, and skills, especially for developing writers. This is a question for future research.

As with reading, it is important to combine explicit and systematic instruction with extended experience with writing for a purpose (Andrews et al., 2006; Graham, 2000; Graham and Perin, 2007a; Hillocks, 1986). It is important to note that most of the evidence-based writing practices suggest the importance of considerable time devoted to writing and the need to practice writing for different purposes. These findings are consistent with qualitative research showing that two practices common among exceptional literacy teachers are (1) dedicating time to writing and writing instruction across the curriculum and (2) involving students in varying forms of writing over time (Graham and Perin, 2007b).

Some foundational writing skills need to be explicitly taught to the point of automaticity. Spelling, handwriting, and keyboarding become mostly automatic for skilled writers (Graham, 2006b), and individual differences in handwriting and spelling predict writing achievement (Graham

et al., 1997), even for college students (Connelly, Dockrell, and Barnett, 2005). Thus, it is important that writers learn to execute these skills fluently and automatically with little or no thought (Alexander, Graham, and Harris, 1998). When these skills are not automatized, as is the case for many developing and struggling writers, cognitive resources are not available for other important aspects of writing, such as planning, evaluating, and revising (McCutchen, 2006). Use of dictation to eliminate handwriting and spelling also has a positive impact on writing performance for children and adults, especially on the amount of text produced (De La Paz and Graham, 1995), although functional writing capability in everyday life probably needs to include the ability to write via other means than dictation. Overall, it is clear that automating what can be automated helps improve writing competence. Some aspects of writing, such as planning or sentence construction, require decisions and cannot be fully automated (Graham and Harris, 2000a). Other, more strategic processes need to be taught and practiced to a point of fluent, flexible, and effective use (Berninger and Amtmann, 2003; Berninger et al., 2006; Graham and Harris, 2003; Graham and Perrin, 2007b).

Instructional environments must be structured to support motivation to write. Although some studies have focused specifically on enhancing motivation to write with positive results (Hidi, Berndorff, and Ainley, 2002; Miller and Meece, 1997; Schunk and Swartz, 1993a, 1993b), the evidence base related to motivation and instruction stems mainly from a few ethnographic, qualitative, and quasi-experimental studies. A small number of experiments show practices that improve the quality of writing and that reasonably could affect motivation to write or engage with writing instruction, although motivation itself was not measured. These practices include setting clear goals for writing; encouraging students to help each other plan, draft, or revise (Graham and Perin, 2007a); use of self-assessment (Collopy and Bowman, 2005; Guastello, 2001); and providing feedback on progress (Schunk and Swartz, 1993a, 1993b). Several single-subject design studies with adolescent learners have demonstrated that social praise, tangible rewards, or both can improve students’ writing behaviors (Graham and Perin, 2007b).