The Adult Education and Family Literacy Act (Title II of the Workforce Investment Act (1998) defines literacy as “an individual’s ability to read, write, and speak in English, compute, and solve problems, at levels of proficiency necessary to function on the job, in the family of the individual, and in society.” The United Nations Education, Social, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2004) defines literacy more broadly as “the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, compute and use printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning to enable an individual to achieve his or her goals, to develop his or her knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in the wider society.”

More than 90 million adults in the United States are estimated to lack the literacy skills for a fully productive and secure life, according to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) (Kutner et al., 2007). This report synthesizes the research on literacy and learning to improve literacy instruction for those served in adult education in the United States and to recommend a more systemic approach to research, practice, and policy.

Conducted in 2003, the NAAL is the most recent national survey of U.S. adult literacy. Adults were defined by the NAAL as people ages 16 years or older. The survey assessed the prose, document, and quantitative literacy of a nationally representative sample of more than 18,000 U.S.

adults living in households and 1,200 prison inmates.1 Adults were categorized as having proficient, intermediate, basic, or below basic levels of literacy.

According to the survey, 43 percent of U.S. adults (an estimated 56 million people) possess only basic or below basic prose literacy skills. Only 13 percent had proficient prose literacy. Results were similar for document literacy: 34 percent of adults had basic or below basic document literacy and only 13 percent were proficient. A comparison of the results with findings from the 1992 National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS) shows that little progress was made between 1992 and 2003 (see Table 1-1).

Table 1-2 shows the percentage and number of adults in each race/ ethnicity category in the 2003 NAAL survey with below basic and basic literacy. Certain groups in the 2003 NAAL survey were more likely to perform at the below basic level: those who did not speak English before entering school, Hispanic adults, those who reported having multiple disabilities, and black adults. The 7 million adults with the lowest levels of skill showed difficulties with reading letters and words and comprehending a simple text (Baer, Kutner, and Sabatini, 2009) (see Table 1-3).

Although literacy increases with educational attainment (see Table 1-4), only 4 percent of high school graduates who do not go further in their schooling are proficient in prose literacy, according to the NAAL; 53 percent are at the basic or below basic level. Among those with a 2-year degree, only 19 percent have proficient prose literacy, 56 percent show intermediate skill, and 24 percent are at basic or below basic levels. This level of literacy might have been sufficient earlier in the nation’s history, but it is likely to be inadequate today (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2005). For U.S. society to continue to function and sustain its standard of living, higher literacy levels are required of the U.S. population in the 21st century for economic security and all other aspects of daily life: education, health, parenting, social interaction, personal growth, and civic participation.

Civic participation requires citizens to understand the complex matters about which they need to make decisions and on which societal well-being depends. Although people might legitimately differ in their beliefs about what health care policy the country should have, national surveys show that too many people lack the literacy needed to engage in that discussion. Parents cannot further their children’s education or ensure their children’s

__________________

1Prose literacy was defined as the ability to search, comprehend, and use information from continuous texts. Prose examples include editorials, news stories, brochures, and instructional materials. Document literacy was defined as the ability to search, comprehend, and use information from noncontinuous texts. Document examples include job applications, payroll forms, transportation schedules, maps, tables, and drug and food labels. The survey also assessed quantitative literacy.

TABLE 1-1 Percentage of U.S. Adults in Each Literacy Proficiency Category by Literacy Task, 1992 and 2003 (in percentage)

|

|

||||||

|

Prose Literacy |

Document Literacy |

Quantitative Literacy |

||||

|

Proficiency Category |

1992 |

2003 |

1992 |

2003 |

1992 |

2003 |

|

|

||||||

|

Below basic |

14 |

14 |

14 |

12a |

26 |

22a |

|

Basic |

28 |

29 |

22 |

22 |

32 |

33 |

|

Intermediate |

43 |

44 |

49 |

53a |

30 |

33a |

|

Proficient |

15 |

13a |

15 |

13a |

13 |

13 |

|

|

||||||

NOTE: Data exclude people who could not be tested due to language differences: 3 percent in 1992 and 2 percent in 2003.

aSignificantly different from 1992.

SOURCE: Data from the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (Kutner et al., 2007).

health when their literacy is low: adults with low literacy are much less likely to read to their children or have reading materials in the home (Kutner et al., 2007), and they have much more limited access to health-related information (Berkman et al., 2004) and have lower health literacy (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). Many U.S. adults lack health literacy or the ability to read and follow the kinds of instructions routinely given for self-care or to family caregivers after medical procedures or hospital stays (Kutner et al., 2006; Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer, and Kindig, 2004).

TABLE 1-2 U.S. Adults in Each Race/Ethnicity Category with Below Basic and Basic Literacy, 2003

|

|

||||||

| Percentage Below Basic |

Percentage Basic |

Estimated Total Number Across Both Categories (in millions) |

||||

|

|

||||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 14 | 32 | 4.1 | |||

| Black | 24 | 43 | 17.8 | |||

| Hispanic | 44 | 30 | 19.7 | |||

| White | 7 | 25 | 49.8 | |||

| Total Number of Adults | 91.4 | |||||

|

|

||||||

NOTES: The NAAL included a national sample representative of the total population in 2003 (222 million people; 221 million in households and a little more than 1 million in prisons). This estimate of the number of people with low literacy (basic or below basic literacy) in each race/ethnicity category is derived from the percentage of people in each category in the NAAL survey. The table does not include the 3 percent of adults who could not participate in the survey due to language spoken or disabilities. It does not include 2 percent of respondents who identified multiple races. These findings are for prose literacy; the pattern of findings is similar for document literacy. For definitions of the literacy categories, see text.

SOURCE: Data from the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (Kutner et al., 2007).

TABLE 1-3 Correct Responses on Reading Tasks for U.S. Adults with Below Basic Literacy (by language of administration) (in percentage), 2003

|

|

||||||||

| Letter Readinga |

Word Identificationb |

Word Readingc |

Comprehensiond | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| English | 80 | 65 | 56 | 54 | ||||

| Spanish | 38 | 74 | 37 | 54 | ||||

|

|

||||||||

NOTES: The data cover 7 million adults, 3 percent of the population. Adults are defined in the survey as people ages 16 and older living in households or prisons. The data exclude adults who could not be interviewed because of language spoken or cognitive or mental disabilities, approximately 3 percent.

aLetter reading required reading a list of 35 letters in 15 seconds.

bWord identification required recognizing words on three word lists of increasing difficulty—from one- to four-syllable words.

cWord reading required decoding of nonwords using knowledge of letter-sound correspondences.

dComprehension required correctly answering a question about the content of a passage written either at grades 2-6 or grades 7-8 level.

SOURCE: Data from Baer, Kutner, and Sabatini (2009).

TABLE 1-4 Percentage of U.S. Adults in Prose and Document Literacy Proficiency Categories by Educational Attainment, 2003

|

|

||||||||

| Below Basic | Basic | Intermediate | Proficient | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Prose | ||||||||

|

Less than/some high school |

50 | 33 | 16 | 1 | ||||

|

GED/high school equivalency |

10 | 45 | 43 | 3 | ||||

|

High school graduate |

13 | 39 | 44 | 4 | ||||

|

Vocational/trade/business school |

10 | 36 | 49 | 5 | ||||

|

Some college |

5 | 25 | 59 | 11 | ||||

|

Associate/2-year degree |

4 | 20 | 56 | 19 | ||||

|

College graduate |

3 | 14 | 53 | 31 | ||||

| Document | ||||||||

|

Less than/some high school |

45 | 29 | 25 | 2 | ||||

|

GED/ high school equivalency |

13 | 30 | 53 | 4 | ||||

|

High school graduate |

13 | 29 | 52 | 5 | ||||

|

Vocational/trade/business school |

9 | 26 | 59 | 7 | ||||

|

Some college |

5 | 19 | 65 | 10 | ||||

|

Associate/2-year degree |

3 | 15 | 66 | 16 | ||||

|

College graduate |

2 | 11 | 62 | 25 | ||||

|

|

||||||||

SOURCE: Data from the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (Kutner et al., 2007).

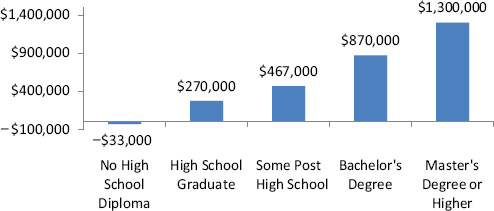

Adults with low literacy also have lower participation in the labor force and lower earnings (Kutner et al., 2007). Figure 1-1 shows how lifetime net tax contributions increase as education level increases. It is reasonable to assume that gains in literacy that allow increases in educational attainment would lead to a higher standard of living and the ability of more people to contribute to such costs of society as public safety and educating future generations. Adults with a high school diploma or general educational development (GED) certificate earn significantly more per year than those without such credentials (e.g., Liming and Wolf, 2008; U.S. Census Bureau, 2007). The most recent national survey of adults’ literacy skills in the United States shows that the percentage of adults employed full time increases with increased facility in reading prose (Kutner et al., 2007).

If anything, data from the NAAL and other surveys and assessments are likely to underestimate the problem of literacy in the United States. Literacy demands are increasing because of the rapid growth of information and communication technologies, while the literacy assessments to date have focused on the simplest forms of literacy skill. Most traditional employment has required reading directions, keeping records, and answering business communications, but today’s workers have very different roles. Employers stress that employees need higher levels of basic literacy in the workplace than they currently possess (American Manufacturing Association, 2010) and that the global economy calls for increasingly complex forms of literacy skill in this information age (Casner-Lotto and Benner, 2006). In a world in which computers do the routine, human value in the workplace rests increasingly on the ability to gather and integrate information from disparate sources to address novel situations and emergent problems, mediate among different viewpoints of the world (e.g., between an actuary’s and a

FIGURE 1-1 Lifetime net tax contributions by education level.

SOURCE: Data from Khatiwada et al. (2007).

customer’s view of what should be covered under an insurance policy), and collaborate on tasks that are too complex to be within the scope of one person. To earn a living, people are likely to need forms of literacy skill and to have proficiencies in the use of literacy tools that have not been routinely defined and assessed.

A significant portion of the U.S. population is likely to continue, at least in the near term, to experience inadequate literacy and require instruction as adults: the most recent main National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) (2009) shows that only 38 percent of twelfth graders performed at or above the proficient level in reading; this achievement was higher than the percentage in 2005 but not significantly different from earlier assessment years. Although 74 percent of twelfth graders were at or above basic, 26 percent were below basic near the end of high school. Table 1-5 shows the percentage of twelfth grade students at each achievement level for reading by race and ethnicity. These numbers include students identified as learning English as a second language: only 22 percent of them were at or above basic reading levels near the end of high school; 78 percent were below basic. Results were similar for twelfth graders with disabilities: 38 percent were at or above basic reading levels; 62 percent were below basic.

Similarly, according to the 2007 assessment of writing by the NAEP, only 24 percent of twelfth graders had proficient writing skills, with many fewer of the students who were learning English or with learning disabilities showing proficiency (40 and 44 percent, respectively) compared with those not identified as English learners or as having a learning disability (83 and 85 percent, respectively).

The NAEP is likely to underestimate the proportion of twelfth graders who need to develop their literacy outside the K-12 system because it does not include students who dropped out of school before the assessment, many of whom are likely to have inadequate literacy. In the 2007-2008 school year, the most recent one for which data are available, 613,379 students in the ninth to twelfth grades dropped out of school. The overall

TABLE 1-5 Percentage of Twelfth Grade Students at or Above NAEP Achievement Levels by Race/Ethnicity

|

|

||||||||

| Asian/Pacific | Black | Hispanic | White | |||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Below basic |

19 | 43 | 39 | 19 | ||||

|

At or above basic |

81 | 57 | 61 | 81 | ||||

|

At or above |

49 | 17 | 22 | 46 | ||||

|

Advanced |

10 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||||

|

|

||||||||

SOURCE: Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) 2009 Reading Assessment (U.S. Department of Education, 2011).

annual dropout rate (known as the event dropout rate—the percentage of high school students who drop out of high school over the course of a given school year) was 4.1 percent across all 49 reporting states and the District of Columbia (National Center for Education Statistics, 2010). Although students drop out of school for many reasons, it can be assumed that these students’ literacy skills are below those of the rest of the U.S. population and fail to meet society’s expectations for literacy. In fact, 55 percent of adults in the 2003 NAAL survey who scored below basic did not graduate from high school (compared with 15 percent of the entire adult population); adults who did not complete high school were almost four times more likely than the total adult population to demonstrate below basic skills (Baer et al., 2009).

Given these statistics, it is not surprising that, although originally designed for older adults, adult literacy education programs are increasingly attended by youths ages 16 to 20 (Hayes, 2000; Perin, Flugman, and Spiegel, 2006). In 2003, more than half of participants in federally funded adult literacy programs were 25 or younger (Tamassia et al., 2007).

The problem of inadequate literacy is also found by colleges, especially community colleges. More than half of community college students enroll in at least one developmental education course during their college tenure to remediate weak skills (Bailey, Jeong, and Cho, 2010). Data from an initiative called Achieving the Dream: Community Colleges Count provide the best information on students’ difficulties in remedial instruction. The study included more than 250,000 students from 57 colleges in seven states who were enrolled for the first time from fall 2003 to fall 2004. Of the total, 59 percent were referred for remedial instruction, and 33 percent of the referrals were specifically for reading. After 3 years, fewer than 4 of 10 students had completed the entire sequence of remedial courses to which they had been referred (Bailey, Jeong, and Cho, 2010). About 30 percent of students referred to developmental education did not enroll in any remedial course, and about 60 percent of those who did enroll did not enroll in the specific course to which they had been referred (Bailey, Jeong, and Cho, 2010). Notably, according to the NAAL survey, proficiency in prose literacy was evident in only 31 percent of U.S. adults with a 4-year college degree.

For a variety of reasons, firm conclusions cannot currently be drawn about whether developmental education improves the literacy skills and rates of college completion. What is clear, however, is that remediation is costly: in 2004-2005, the costs of remediation were estimated at $1.9 to $2.3 billion at community colleges and another $500 million at 4-year colleges (Strong American Schools, 2008). States have reported tens of millions of dollars in expenditures (Bailey, 2009). The costs to students of inadequate remediation include accumulated debt, lost earnings, and frustration that can lead to dropping out.

STUDY CHARGE, SCOPE, AND APPROACH

To address the problem of how best to instruct the large and diverse population of U.S. adults who need to improve their literacy skills, the U.S. Department of Education asked the National Research Council to appoint a multidisciplinary committee to (1) synthesize research findings on literacy and learning from cognitive science, neuroscience, behavioral science, and education; (2) identify from the research the main factors that affect literacy development in adolescence and adulthood, both in general and with respect to the specific populations served in education programs for adults; (3) analyze the implications of the research for informing curricula and instruction used to develop adults’ literacy; and (4) recommend a more systemic approach to subsequent research, practice, and policy. The complete charge is presented in Box 1-1.

The work of the Committee on Learning Sciences: Foundations and Applications to Adolescent and Adult Literacy is a necessary step toward improving adult literacy in the United States. Through our work, which included public meetings and reviews of documents, the committee gathered evidence about adult literacy levels both in the United States and internationally and the literacy demands placed on adults in modern life related to education, work, social and civic participation, and maintenance of health and family. We considered a wide array of research literatures that might have accumulated findings that could help answer the question of how best to design literacy instruction for adults.

Conceptual Framework and Approach to the Review of Evidence

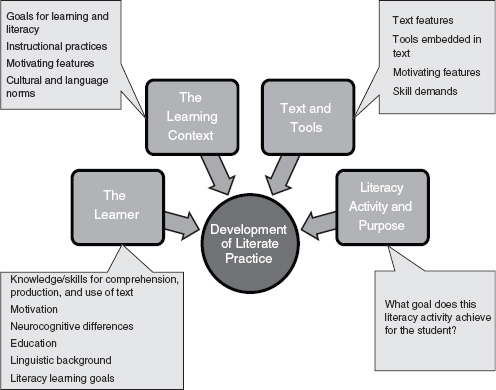

Figure 1-2 presents the committee’s conceptual model of the development of literate practice, which we used to identify research most germane to this report. We also used it to convey the range of factors that require attention in our attempt to identify the instructional practices that work for learners and the conditions that support or impede instructional effectiveness and learning. The model focuses mainly on the factors that research shows are amenable to change through particular approaches to instruction and the creation of supportive learning environments. It is derived mainly from understandings of literacy development from K-12 populations and extended to accommodate adults’ motivations and circumstances, which differ from those of younger populations learning to read and write.

In view of the charge that motivates this report, we define literacy to be the ability to read, write, and communicate using a symbol system (in this case, English), with available and valued tools and technologies, in order to meet the goals and demands of families, individuals, and U.S. society. Literacy requires developing proficiencies in the major known components

BOX 1-1

Committee Charge

In response to a request from the National Institute for Literacy (NIFL), the National Research Council will convene a committee to conduct a study of the scientific foundations of adolescent and adult literacy with implications for policy and practice. In particular, the study will synthesize research-based knowledge on literacy from the multidisciplinary perspectives of education, cognitive and behavioral science, neuroscience, and other relevant disciplines; and will provide a strong empirical foundation for understanding the main factors that affect literacy learning in adolescence and adulthood generally and with respect to the specific populations served by adult education. The committee will develop a conceptual and methodological framework to guide the study and conduct a review of the existing research literature and sources of evidence. The committee’s final report will provide a basis for research and practice, laying out the most promising areas for future research while informing curriculum and instruction for current adolescent literacy and adult education practitioners and service providers.

This study will (1) synthesize the behavioral and cognitive sciences, education, and neuroscience research on literacy to understand its applicability to adolescent and adult populations; (2) analyze the implications of this research for the instructional practices used to teach reading in adolescent and adult literacy programs; and (3) establish a set of recommendations or roadmap for a more systemic approach to subsequent research, practice, and policy. The committee will synthesize and integrate new knowledge from the multidisciplinary perspectives of behavioral and cognitive sciences, education, neuroscience, and other related disciplines, with emphasis on potential uses in the research and policy communities. It will provide a broad understanding of the factors that affect typical and atypical literacy learning in adolescence and adulthood

of reading and writing (presented in Chapter 2) and being able to integrate them to perform the activities required of adults in the United States in the 21st century. Thus, our use of the term literacy skill includes but encompasses a broader range of proficiency than basic skills.

Our synthesis covers research literature on

• cognitive, linguistic, neurobiological, social, and cultural factors that are part of reading and writing development across the life span;

• effective approaches for teaching reading and writing with students in K-12 education, out-of-school youth, and adults;

• principles of learning that apply to the design of instruction;

• motivation, engagement, and persistence;

• uses of technology to support learning and literacy for adolescents and adults;

• valid assessment of reading, writing, and learning; and

generally and with respect to the specific populations served by adult education and such related issues as motivation, retention and prevention.

The following questions will be among those the committee will consider in developing its roadmap for a more systematic approach to subsequent research, practice, and policy:

• Does the available research on learning and instruction apply to the full range of types of learners served by adult education? If not, for what specific populations is research particularly needed? What do we know, for example, about how to deliver reading instruction to students in the lowest achievement levels normally found in adult basic education?

• What are some of the specific challenges faced by adults who need to learn literacy skills in English when it is their second language? What does the cognitive and learning research suggest about the most effective instructional strategies for these learners?

• What outcome measures and methods are suggested from research addressing literacy remediation and prevention in both adolescent and adult programs?

• Where are there gaps in our understanding about what research is needed related to retention and motivation of adult literacy learners?

• What implications does the research on learning and effective instruction have for remediation and prevention of problems with literacy during middle and/or high school?

• What is known about teacher characteristics, training, and capacity of programs to implement more effective literacy instructional methods?

• Are there policy strategies that could be implemented to help ensure that the evidence base on best practices for learning gets used by programs and teachers?

• instructional approaches for English language learners and the various influences (cognitive, neurobiological, social) on the development of literacy in a second language in adulthood.

Several reviews of research relevant to the charge informed the work of this committee, among them a report of the National Reading Panel (NRP) (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000) and a recent systematic review of the literature on adult literacy instruction (Kruidener, MacArthur, and Wrigley, 2010). In such cases, we did not duplicate existing works but incorporated from previous work the core findings that we interpreted to be most relevant to our charge, augmented with targeted searches of literature as needed to draw conclusions about the state of the research base and needs for development.

We included both quantitative and qualitative research with the recognition that different types of research questions call for different methodological approaches. We concentrated mainly on the most developed

FIGURE 1-2 Conceptual model of the development of literate practice.

research findings and included promising, cutting-edge areas of inquiry that warrant further research. In reviewing the research, we asked: Are the data reliable and potentially valid for the target population? What are the limits of current knowledge? What are the most useful directions for expanding knowledge of literacy development and learning to better meet the needs of adult learners?

An assumption of our framework is that to be functionally literate one must be able to engage in literacy practices with texts and tools that are demanded by and valued in society. Thus, we include a focus on writing, which has a smaller base of research than reading. We also refer throughout the report to new literacy skills and practices enabled by a digital age and include a more complete discussion of these issues in Appendix B. Although we assume that literacy skills enabled by the use of new technologies are now fundamental to what it means to be literate, researchers are only beginning to define these skills and practices and to study the instruction and assessments that develop them in students of all ages (e.g., Goldman et al., 2011). In the final chapter, we stress the importance of including writing and emerging new literacy demands in any future efforts to define literacy

development goals for adults and to identify the instructional approaches that comprehensively meet their skill development needs.

An examination of the relevant literatures revealed a diverse range of information and disparate literatures that seemed unknown and unconnected to each other, despite the fact that many share a focus on reading and literacy. The literatures differ in the ages of the populations studied; definitions, theories, and working understandings or models of literacy development; research topics; and research methods. Several literatures were severely underdeveloped with respect to the charge because of the nature of the topics studied or because the data are mainly descriptive or anecdotal and have not yet led to the accumulation of reliable or relevant knowledge. This information gathering led the committee to focus the charge in these ways.

We focused on a target population (to whom we refer generally as “adults”) of individuals ages 16 and older not in secondary education, consistent with eligibility requirements for participation in federally funded adult literacy education programs. We considered what is known about the literacy skills and other characteristics of these adults and their learning environments in programs of four general types: (1) adult basic education, (2) adult secondary education (e.g., GED instruction), (3) programs of English as a second language, and (4) developmental (remedial) education courses in colleges for academically underprepared students. We focused mainly on research that could be applied to the development of instructional methods for these populations, and we did not focus more broadly on segments of the U.S. population, such as the elderly, who might benefit from enhanced literacy or strategies that compensate for age-related declines in literacy skills.

The lack of research on learning and the effects of literacy instruction in the target population is striking, given the long history of both federal funding, albeit stretched thin, for adult education programs and reliance on developmental education courses to remediate college students’ skills. As we explain in Chapter 3, although there is a large literature on adult literacy instruction, it is mostly descriptive, and the small body of experimental research suffers from methodological limitations, such as high rates of participant attrition and inadequate controls. As a result, the research has not yielded a body of reliable and interpretable findings that could provide a reliable basis for understanding the process of literacy acquisition in low-skilled adults or the design and delivery of instruction for this population.

In contrast to the scant literature on adult literacy, a large body of research is available with younger populations, especially children. Although

the majority of this work investigates the acquisition and instruction of word-reading skills, more is becoming known about how to develop vocabulary and reading comprehension. A growing body of research with adolescents in school settings focuses on such topics as academic literacy, disciplinary literacy, and discussion-based approaches that warrant further study with both adolescents and adults outside school. Although major research studies have been launched by the U.S. Department of Education, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and others to increase knowledge of literacy development and effective instruction beyond the early elementary years, the efforts are too new to have produced numerous peer-reviewed publications on effective instructional practices. Similarly, research on adult cognition, learning, and motivation from other disciplines is constrained for our purposes. For the most part, such research relies on study samples of convenience (e.g., college students in introductory psychology courses) or the elderly.

Given the dearth of research on what is the target population for this report, the committee has drawn on what is available: extensive research on reading and writing processes and difficulties in younger students, a mature body of research on learning and motivation in relatively well-educated adults with normal reading capability, and comparatively limited research on struggling adolescent readers and writers and adult literacy learners. These constraints on the available literature mean the committee’s analysis and synthesis focus on examining instructional practices that work for younger populations that have not been invalidated by any of the available data with adults; extrapolating with caution from other research available on learning, cognition, and motivation to make additional suggestions for improving adult reading instruction; and articulating a research agenda focused specifically on learning and reading and writing instruction for adult literacy learners. The committee decided that examining the wealth of information from the research that exists with these populations could be valuable to the development of instructional practices for adults, with research and evaluation to validate, identify the boundaries of, and expand this knowledge in order to specify the practices that develop literacy skills in adolescents and adults outside school.

Although the charge specified a focus on reading, we chose to add a focus on writing for four reasons. First, integrated reading and writing instruction contributes to the development of both reading and writing skills, as described in Chapter 2, most likely because these skills require some of the same knowledge and cognitive and linguistic processes. Second, from a practical perspective, many reading activities for academic learning or work also involve writing (and vice versa). Third, writing is a method of developing content knowledge, which adults need to develop to improve their reading, both in general and in specific content domains. Fourth, writing is

a literacy skill that is important to adult literacy education, given that it is needed for GED completion and for success in college and in the workplace (Berman, 2001, 2009; Carnevale and Derochers, 2004; Kirsch et al., 2007; Milulecky, 1998; National Commission on Writing, 2004, 2005).

Because of the large variety of literatures, the report does not focus in depth on domain-specific literacies, such as quantitative literacy, financial literacy, health literacy, or science literacy. These topics are large and significant enough to deserve separate treatment (e.g., Condelli, 2006; Nielsen-Bohlman et al., 2004).

The report includes research about literacy development with adolescents of all ages as well as children. However, given the breadth of the charge and in consultation with the project sponsor about the primary interest, the committee narrowed its focus to synthesizing the implications of that research for instruction in adult literacy education (defined as instruction for individuals 16 years and older and outside K-12 education). This focus was chosen to fit with the requirement that federally funded adult literacy programs are for youth and adults older than 16 and not in the regular K-12 system. Although there is a broad universe of information on adolescent and adult literacy and the factors that affect literacy, the committee and this report covers the research findings about the factors that affect literacy and learning that are sufficiently developed and relevant for making decisions about how to improve adult literacy instruction and planning a research agenda. Consistent with the sponsor’s guidance, we did not address the question of how to prevent low literacy in U.S. society, but the pressing and important problem of how to instruct adolescents and adults outside the K-12 system who have inadequate English literacy skills. Although the report does not have an explicit focus on issues of prevention and how to improve literacy instruction in the K-12 system, many of the relevant findings were derived from research with younger populations, and so they are likely to be relevant to the prevention of inadequate literacy.

The discussion of research relevant to the population of adult learners is complicated by substantial differences in the characteristics of learners, learning goals, and the many and varied types and places of instruction. In theory, it is possible to organize this report according to any number of individual difference variables, learning goals (e.g., GED, college entrance, parental responsibilities, workplace skills), general type of instruction (adult basic education, adult secondary education, English as a second language), places of instruction, or various combinations. As Chapter 3 of the report makes clear, however, it is premature, given the limits of the research available, to disentangle the research along these dimensions. On one hand,

learners across the many places of instruction share literacy development needs, learning goals, and other characteristics; on the other hand, learners at a single site vary in these characteristics. In many instances, it would not be possible to know how to categorize the research because research reports do not specify the place of instruction, describe the goals of instruction, or clearly and completely describe the study participants. Indeed, one of the critical needs for future research is to systematically define segments of the population to identify constraints on generalizing research findings and specific features of instruction that might be needed to effectively meet the needs of particular subgroups.

Thus, this report is organized according to the major topics that deserve attention in future research to develop effective instructional approaches. The topics reflect those about which most is known from research—albeit mostly with populations other than one that is the focus of our study—and that have the greatest potential to alleviate the personal, instructional, and systemic barriers that adults outside school experience with learning.

Chapter 2 provides an overview of what is known about the major components and processes of reading and writing and the qualities of instruction that develop reading and writing for both typical and struggling learners in K-12 settings. The chapter presents principles for intervening specifically with struggling learners. Although supported by strong evidence, we stress that caution must be used in generalizing the research to other populations. Translational research is needed on the development of practices that are appropriate for diverse populations of adolescents and adults.

Chapter 3 describes the adults who receive literacy instruction, including major subgroups, and the demographics of the population, what is known about their difficulties with component literacy skills, and characteristics of their instructional contexts. The chapter conveys the state of research on practices that develop adults’ literacy skills and identifies priorities for research and innovation to advance knowledge of adult literacy development and effective literacy instruction.

Chapters 4 through 6 synthesize research from a variety of disciplines on topics that are vital to furthering adult literacy. Chapter 4 summarizes findings from research on the conditions that affect cognitive processing and learning. The chapter draws on and updates several recent efforts to distill principles of learning for educators and discusses considerations in applying these principles to the design of literacy instruction for adults. Chapter 5 synthesizes research on the features of environments—instructional interactions, structures, tasks, texts, systems—that encourage engagement with learning and persistence in adolescents and adults. The chapter draws on research from multiple disciplines that examine the psychological, social, and environmental factors that affect motivation, engagement in learn-

ing, and goal attainment. Chapter 6 applies what is known about literacy, learning, and motivation to examine in greater depth one aspect of the instructional environment—instructional technologies—that may motivate essential practice with literacy activities, scaffold learning, and help to assess learners’ progress. Technology also may help to resolve some of the practical barriers to more extensive literacy practice related to life demands, child care, and transportation, which adult learners cannot always afford, in either dollars or time.

The next two chapters discuss the research for two subgroups of the adult learner population. Chapter 7 synthesizes what is known about the cognitive, linguistic, and other learning challenges experienced by adults with learning disabilities and the uses of accommodations that facilitate learning. Chapter 8 considers the literacy development needs and processes for the population of adults learning English as a second language, which includes both immigrants and U.S. citizens and is diverse in terms of education, language background, and familiarity with U.S. culture. This chapter points to the major challenges experienced by English language learners in developing their literacy skills and outlines the research needed to facilitate literacy development. Given that the basic principles of reading, writing, learning, and motivation have been discussed in previous chapters, this chapter focuses on issues specific to the literacy development of adults who are learning a second language.

Chapter 9 presents the committee’s conclusions and recommendations in light of the research reviewed in previous chapters. Our conclusions stress that it should be possible to develop approaches that improve adults’ literacy given the wealth of knowledge that exists. The challenge is to determine how to integrate the various principles we have derived from the research findings into coordinated and comprehensive programs of instruction that meet the needs of diverse populations of adults. In this final chapter, we urge attention to several issues in research and policy that impinge directly on the quality of instruction, the feasibility of completing the much-needed research, and the potential for much broader dissemination and implementation of the practices that emerge as effective.