3

State Insurance Exchanges’

Impact on Consumers

HOW CONSUMERS SHOP FOR HEALTH INSURANCE:

LESSONS FOR EXCHANGE DESIGNERS

Lynn Quincy, Senior Health Policy Analyst

Consumers Union

State health insurance exchanges carry out several tasks: they certify health plans, provide outreach to consumers, conduct eligibility determinations, describe health plan choices to consumers, and enroll and disenroll beneficiaries. Quincy said that exchange designers must start with a nuanced understanding of how consumers shop for health insurance to successfully attract consumers, manage their expectations, and allow them to make a meaningful choice among health plan options.

According to three studies conducted by Consumers Union, the image of a careful shopper who is capable of weighing the myriad costs and benefits associated with their health insurance options must be abandoned (Consumers Union and People Talk Research, 2010; Kleimann Group and Consumers Union, 2011a,b). Table 3-1 provides an overview of these studies. The first two studies examined different components of a health insurance disclosure form developed by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). As required by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the form must be used by the exchanges and all plans (e.g., grandfathered plans, nongrandfathered plans, individually purchased plans, group plans). A third study was conducted, independently of the NAIC work, to assess how consumers respond to actuarial value concepts.

TABLE 3-1 Three Consumer’s Union Studies of Consumer Health Insurance Shopping Behavior

|

|

||

| Study examined | Study date | States where study was conducted (midsized cities) |

|

|

||

| Pages 1–4 of new health insurance disclosure form “Coverage facts” label (pages 5–6) | Sept.–Oct. 2010 | Iowa, New Hampshire, California, Ohio Missouri, New York |

| May 2011 | ||

| Actuarial value concepts | May 2011 | Colorado, Maryland |

|

|

||

SOURCE: Quincy, 2011.

Participants of the three studies were evenly divided between men and women, as well as individuals who were uninsured and insured (with nongroup coverage). Participants represented a variety of education levels, ages (26 to 64), race and ethnic backgrounds, and familiarity with health insurance. The testing sessions were held in 2010 and 2011.

According to the studies, consumers dread shopping for health insurance. This became clear as the researchers engaged consumers in simulated shopping exercises. Quincy reported that one participant became so anxious that he almost left upon learning that the focus group session related to health insurance. One focus group participated stated “I think medical insurance is probably one of the hardest things for me that I shop for. And I think it’s one of the hardest things to figure out what’s covered” (Consumers Union and People Talk Research, 2010).

The implications for exchange designers is they have to increase the appeal of shopping for health insurance through the exchange and they have to minimize the aspects of the experience that cause dread, Quincy said.

Another finding from the research is that many consumers doubt the value, or question the purpose, of health insurance. Many view health insurance as prepaid health care rather than health insurance. If the anticipated annual out-of-pocket expenses for health care are less than the cost of insurance premiums and the plan deductible, consumers often feel that insurance is not a good value. The critical concept that is missing is that insurance protects individuals and families from unexpected health crises. Many consumers do not understand this basic principle of insurance, Quincy said. This finding suggests that the exchanges will need to provide health insurance education. Consumers will not be in a position to choose a plan if they do not understand the basic value and purpose of health insurance. Health insurance education will have to be provided in a compelling, multilayered, just-in-time approach. To reduce cogni-

tive burden, the information can be parceled out in manageable bites. A valuable teaching tool evident in the research is showing consumers how much a health plan would pay for a very serious illness. This allowed consumers to appreciate the value of health insurance.

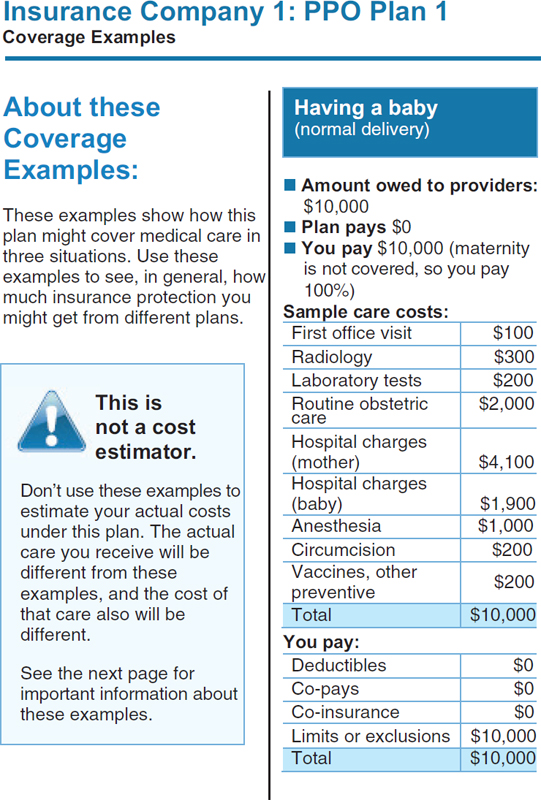

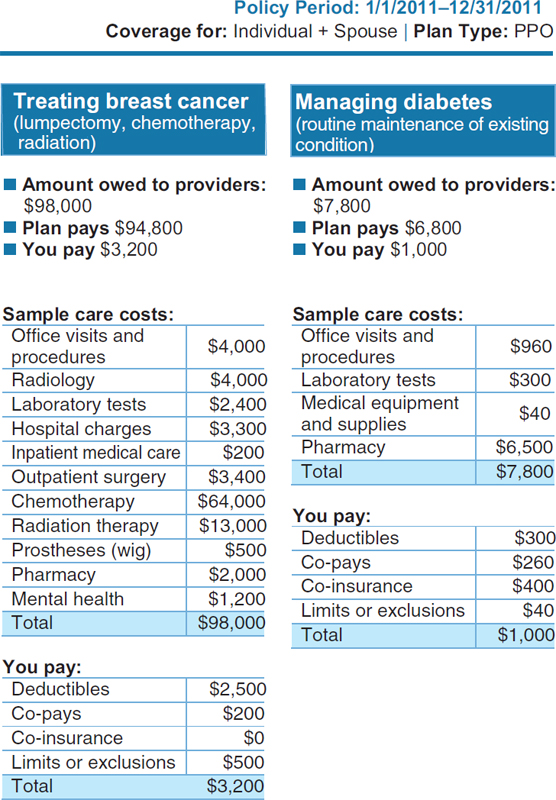

Page 5 of the Health Insurance Disclosure Form is shown in Figure 3-1. This page conveys information on costs for some medical scenarios. This page shows how much of the claim is paid by the insurer and how much is paid by the consumer. Consumers found these scenarios very informative, Quincy said. Many study subjects had no idea how much medical care costs. Individuals could identify with the scenarios (e.g., “I might get breast cancer”), and the plan payment amounts allowed consumers to judge the extent of coverage and compare the value of the plans. The research demonstrated that consumers care very much about value. Consumers’ notion of value is sophisticated, Quincy said. It encompasses the scope of services covered, the share of the cost paid by the plan, and the quality of the providers that are available within the plan. Consumers do not want the lowest-cost plan; they want the best-value plan they can afford. However, figuring out the “value” of any given health plan is a challenge for consumers. One barrier to understanding value is confusion over cost-sharing terms. Consumers may have heard the term deductible, but many do not know what it means. Other terms that are unfamiliar or misunderstood include co-insurance, benefit maximum, allowed amount, and out-of-pocket maximum. This difficulty is not surprising. The underlying concepts are complex, and they must be used together to estimate patient costs for services (e.g., do co-payments count toward the deductible? the out-of-pocket maximum?).

Quincy highlighted the challenges associated with health insurance jargon and the need to make the underlying concepts understandable. She acknowledged that plain language considerations are important but insufficient. For example, a consumer may need to understand not only what a co-payment is but also whether it counts toward the deductible. This is a different exercise than simply understanding the meaning of co-payment and deductible. There is much work to be done to provide consumers with language substitutes for the common health insurance terms that are in use, Quincy said.

The computations that consumers must undertake to assess a plan’s value are enormously complicated. Many consumers do not have the skills, health insurance familiarity, and confidence needed to calculate their share of costs. Medical terms are also confusing, Quincy said. According to the consumer research, individuals do not fully understand the difference between primary and preventive care. Other unfamiliar terms include specialty drugs and deciphering the difference between

diagnostic tests and screening tests. When such tests are reimbursed differently, it is important to understand this distinction.

In terms of the implications for exchange designers, it is clear that the cognitive load will be considerable for many consumers. When the cognitive load is too great, individuals will use cognitive shortcuts to get through the task of shopping for coverage. Exchange designers need to understand and take charge of these shortcuts, Quincy said. The consumer’s shortcuts might take the form of, “Well, Blue Cross/Blue Shield—I’ve heard of them. I’m going to select that plan.” Or, “I’m not going to make a choice, it’s too hard. I’m just going to let them reenroll me in the plan I was in last year.” Or, “I’m going to ask my neighbor what she is in, and I’ll enroll in that plan.”

State insurance exchanges could instead provide cognitive shortcuts to consumers that are vetted and provide meaningful help with their health insurance shopping. One mechanism contemplated by the ACA is the provision of actuarial value tiers. These preset tiers (platinum, gold, bronze, and silver) allow consumers to see the relative value of their health plan choices. Another shortcut would be an understandable measure of network adequacy. The Coverage Facts Label shown in Figure 3-1 is an example of a shortcut. It allows consumers to quickly compare plans and see what they would pay for a standardized medical scenario.

Quincy said that consumers need a mental map to navigate a complex topic like health insurance. If this map or framework is missing, decision aids such as glossaries or well-designed disclosure forms can do little to help consumers—there is nothing to which they can attach the information. Consumers without a framework need to be provided with one. Without an accurate “map” of how insurance works and what its purpose is, consumers may make incorrect assumptions. Many individuals use their prior experience with health insurance as a framework. For example, an individual might say, “Well, in my last plan, co-payments counted toward the deductible so I assume it works this way.” Or, someone who previously had employer coverage, which almost always covers maternity, purchased a plan on her own without realizing that maternity wasn’t included … and then became pregnant.

If individuals do not have prior experience with health insurance, they may use the experience they have with other types of insurance, Quincy said. For example, with automobile insurance, individuals pay a deductible every time the car is repaired. Some testing participants assumed that health insurance deductibles worked the same way, meaning it had to be paid every time you become ill, not once a year.

Quincy said that information that is provided about health insurance must be from a trusted source. If consumers do not trust information,

they will not use it. Trust levels are very low for health insurers. Even when consumers have a good grasp of the information in front of them, they often do not trust their analyses. They worry about the “fine print” because health insurers are “tricky.”

State health insurance exchanges need to cultivate an image as a trusted source of information, Quincy said. It is very important for exchanges to manage consumer expectations and to not oversell what they can do for consumers. If there are unmet expectations, it will take many years to overcome the negative perception. Exchanges might want to partner with a trusted entity, preferably a local organization, to build trust in the health plan information provided. More importantly, the exchanges and the health plans operating inside of them have to merit consumer trust. To do so, they will have to vet health plans well, strive for stability in offerings, invest in good communications, test communications with consumers, and engage in these activities over the long run.

There is substantial consumer decision-making research to support the notion that consumers need a manageable number of choices, Quincy said. Given the cognitive difficulty of evaluating their choices, consumers do not want an unlimited number of health insurance choices. Quincy said that if an exchange did everything right—if the products were clearly described, assistance were provided, consumers had a mental map, the products were trusted—and it gave consumers 100 choices, the process would be a failure because consumers cannot manage that many choices. A better strategy is to offer consumers a manageable number of “good” (vetted) choices. Consumer testing in Massachusetts led that exchange to reduce the number of choices from 27 to 9.

To ease the cognitive burden, it is advisable to reduce the number of features that can vary between plans to make them easier to compare. The ACA standardizes some aspects of benefit design, but exchanges should consider additional standardization as they gain experience with consumers use of the exchange.

Based on these consumer testing results, as well as the enrollment experience of many coverage programs, it is clear that some consumers will also need one-on-one assistance choosing a health plan and understanding the implications of their choice, Quincy said. Navigators can facilitate consumer understanding, but exchanges should arm the navigators with consumer-tested tools and decision aids.

Quincy concluded her presentation with a number of recommendations for consideration:

• Craft a widely accepted definition of health insurance literacy and develop a tool for measuring health insurance literacy in consumers.

• Develop standards for products that go beyond plain language standards and address all aspects of health insurance literacy.

• Rigorously test all products that interface with the consumer, and engage in continuous monitoring of consumer reactions to their exchange experience.

• Establish strong marketing rules for insurers inside and outside the exchange, so consumer confusion is not exploited.

THE CHALLENGE OF HEALTH INSURANCE LANGUAGE OR

COMMUNICATION WITH VULNERABLE POPULATIONS

Yolanda Partida, M.S.W., D.P.A.

Hablamos Juntos

Understanding how language works is important to effective communication about health insurance options, Partida said. Language is a system of arbitrary signals. Thoughts and feelings are communicated through voice sounds, gestures, or writing symbols. Individuals interpret information in some context and draw upon signals that are part of discourse (the environment, setting, and nonverbal gestures) to infer meaning. A language of a nation, people, or other distinct community is a unique and shared system of rules for combining its components such as words and gestures. A dialect is a language shared by members of a group, jargon specific to a domain (e.g., the dialect of science), an occupation, or region (American Heritage, 2009).

Partida said that it is generally accepted that language is acquired and learned over time through social interactions, experiences, and formal and informal education. In a sense, language is a window on how the human mind works. Mental and social constructs are embedded in language to describe thoughts, interpret meaning, and interact with others (Gasser, 2006). Some suggest that the acquisition of language is instinctual and that the evolution of the human brain has resulted in an innate ability to organize and recall words and concepts (Pinker, 1994). Other scholars posit that the units of language (elements of form, words, grammatical patterns, conventions of usage) are in some sense also units of cognition. Linguists and cognitive scientists contend that language influences how people think and view the world around them. Moreover, language is constantly changing to reflect new and evolving social and cultural realities. New words and terms such as Googling and wiki-like and health insurance exchanges become incorporated into the lexicon.

Language reflects our lived experience and environment, Partida said. Where a person lives gives form to a defined culture and view of the world that serves as platform for interpersonal interactions that is

drawn upon to create order and understanding. Entering a new setting or environment can be disorienting or can test the limits of our ability to infer meaning. Partida recalled her first day on the job as a medical social worker walking into a neonatal intensive care unit. Though this environment was familiar and routine to the staff who worked there, it presented a cultural shock to Partida. She pointed out that we become acclimated to environments in which we live and work. Our daily experiences inform how we see and understand these environments and more broadly, the world around us. Soon, our language, the words we use, and how we interpret or make sense of events, is shaped by what we have come to know and what we have experienced. Moreover, it is natural to assume that others see the world as we do.

Immigration, leaving our birth country to live in a new country, can dramatically change our lived experience, Partida said. It is not hard to imagine how geographic relocation can lead to vastly different lived experiences. The children of immigrants come to know about the old country through their parents and communities of immigrants from the same country. New foods, clothing items, and other goods and products become part of these newly changed environments. Local conditions and community response to changing demographics influence how local health care delivery systems and insurance products are viewed by newcomers—either as helpful resources or difficult challenges to be avoided.

Overcoming language differences is critical to integration and economic success for both new arrivals and their new chosen communities, Partida said. How language is learned influences competencies. Many U.S. immigrants are heritage speakers. These are primarily second-generation immigrants, primarily children who learn the language of their parents at home and then learn English as they go to school. This way of acquiring a new language is different than learning a foreign language through formal study, where an individual chooses to study the language. With formal language training, a teacher is available to explain the new language’s structure and rules. Heritage speakers have to learn these aspects of the language on their own. With the lack of formal training, heritage speakers can exhibit wide variations in their level of language comprehension. More important, independent language learning can result in poor English mastery, language adaptations, and language mixing. Using English and Spanish within the same sentence and blending of English and Spanish to create new words is characteristic of heritage speakers. So much so that blended words such as lonche (lunch), dompe (dump), and yonke (junk) are commonly used and have become incorporated in the lexicon of bilingual and bicultural communities in the United States.

Another form of language acquisition is second language learning,

which takes place when an individual is in a different country where another language is spoken. Second language learning is usually informal, resulting in variable levels of proficiency and little or no written skills, Partida said. Vocabulary and speech may be adapted to include everyday language or specialized language, such as language related to medical care or health insurance.

Nearly 70 percent of Spanish speakers in the United States speak Mexican Spanish. Spanish is the primary language of 22 countries; however, the Spanish spoken in Spain differs from that spoken in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central and South America. Spanish may also be distinct for heritage speakers who learn Spanish in an English-speaking context. The way Spanish is spoken by heritage speakers who learn Spanish in an English-speaking context is also distinct. Some contend that the grandchildren of today’s new immigrants will hardly speak the language of their ancestors.

Each language is different, with unique features that require special consideration, Partida said. The lessons learned from translating Spanish to English may not be at all applicable when translating another language into English. For Spanish, because of a high risk for poor first language mastery and rate of attrition, language development history is an important consideration in soliciting opinions about translated materials. For Chinese, there are five regional languages that are spoken (Cantonese and Mandarin are the most well known) and there are two writing systems, simplified and traditional. Simplified Chinese is based mostly on cursive (caoshu) forms embodying graphic or phonetic simplifications of the traditional forms. This simplified form is popular and has been promoted to improve literacy. It is officially used in the People’s Republic of China (Mainland China), Singapore, Malaysia, and at the United Nations. The graphic traditional writing form used in printed text for over a thousand years are used in the Republic of China (Taiwan), Hong Kong, and Macau. Overseas Chinese communities typically use the traditional characters, but simplified characters are gradually gaining popularity among mainland Chinese emigrants. When translating or designing written materials, the language and communication practices of the target population need to be understood. For Chinese populations, regions of origin can help determine the best writing style to use, Partida said.

Partida pointed out that health communication often contains vocabulary associated with specialized domains of knowledge, such as medicine, biology, physics, and insurance products and practices. Even when there is a shared language and culture between providers and the population they serve, domain knowledge and associated language may interfere with effective communication. The lexicon of medical professionals includes vocabulary and concepts associated with anatomy, physiology,

and other science-based fields. Those seeking health care are more likely to draw upon informal or experience-based knowledge of the human body and to use general language to describe symptoms such as pain. They may not know the names of internal organs and what they do, nor really understand how the human body works, nor have meaningful or shared vocabulary to differentiate one kind of pain from another.

Differences in domain knowledge can be as significant as cultural and language differences, Partida said. Insurance and medical language include common vocabulary to represent activities or responsibilities tightly fitted into business practices (e.g., single limit, endorsement, deductible, coverage maximums) that are often poorly understood as intended by those outside these fields. Key concepts and specialized meaning assigned to industry terms (e.g., enroll, coverage, single limit) may need to be taught to new members and understanding may need to be verified, perhaps using techniques such as the teach-back method.

Health organizations face several challenges in acquiring health materials in languages other than English. On the whole, the industry relies on translation of materials developed for English audiences. Translation quality research suggests that novice and/or untrained translators often adopt a literal, linguistic, micro-approach to the translation task, and become a source of poor-quality translations. Moreover, the underlying communicative objective of written materials (text) may not be overtly visible. The overall design and layout of written materials influence how a text conveys meaning. But without explicit guidance about the communicative objective (the purpose to be served by a text and how it is to be used), the objective may not be apparent to even highly trained translators (Colina, 1997, 1999). Understanding the art and practice of translation is essential for quality translations. For example, specialized terms (product or program names, destinations within a facility) may be literally translated if the intended use and meaning are not made clear.

Translators, the language professionals who take these jobs, vary in their language skills, Partida said. The highly specialized nature of health insurance language, often framed in contractual terms, represents significant challenges, even for translators with advanced training. Without guidance, translations of highly specialized content are likely to produce severely more opaque or misleading materials. The reason is basic: language and culture are intertwined. Health insurance language is part of a larger system of health practice, health policy, and payment structures. Translating words independent of the larger system is like writing without context. Even translation professionals with advanced training are likely to produce translations with high variability in how industry terms are translated. Useful translations will require reinterpretation of con-

tent in the cultural context, language, and value set of the new intended reader. This should not be done by translators in a vacuum.

Experienced and well-trained language professionals, translators, and interpreters also pay attention to language patterns common to first languages spoken within an English context. Over time, the language use of immigrants is likely to reflect living and working in English-dominate society. Much formal language used in health encounters and health insurance materials reflect the nation’s practices and policies.

Many translated materials tend to retain English language structure, and easily available machine translation programs such as Google’s translation software render literal translations. The range of translation software has expanded in recent years, and many show vast improvements, but none replace the need for a critically thinking language professional with advanced knowledge in the pair language (e.g., English–Spanish, English–Simplified Chinese), Partida said. Another barrier to translation quality is a steady decline in understanding the differences in language structure.

Language is constantly evolving and adapting to broader sociocultural changes in the environment. The Spanish spoken in the United States reflects socioeconomic conditions and health care practices, Partida said. Translators, particularly those living and working in other countries, may not understand the context in which translated materials will be used and the business practices associated with a market-driven health care system. Dictionaries may be useful for some health system language, but some practices have no equivalent in the Spanish lexicon. The quality of a translation may be difficult to judge, and translation of industry vocabulary may be highly variable from one translator to another, and even from one document to another provided by the same health care provider. Variability in how industry terms and practices are translated increases the comprehension challenge for users of translated materials and can be avoided with industry adoption of translation standards.

Partida discussed a Spanish glossary developed through Hablamos Juntos. The project produced an Excel database with recommended standards for translating 237 difficult-to-translate health plan industry terms for the Los Angeles (L.A.) Care Health Plan, a plan serving residents of Los Angeles County. L.A. Care Health Plan and partner health plans expressed long-standing concerns over translation quality and with inconsistencies in translations among the translation vendors they contracted with. California Health and Safety Code (section 1367.04) requires health plans to assess the linguistic needs of their members and to provide for translation and interpretation for populations meeting specified thresholds. For L.A. Care Health Plan this meant translating health plan materi-

als into 10 languages.1 At the time, there was an expected change advocated by health plans with the potential to reduce this to five languages. Hablamos Juntos produced three glossaries of terms—one in Spanish, one in simplified Chinese, and another in traditional Chinese—that are the property of L.A. Care Health Plan. The glossary consists of the 237 health plan terms, their definitions, parts of speech, and a recommended translation standard. Additional notes and comments were provided on factors influencing the use of the recommended translation and dealing with unique populations, for example, by providing low literacy options for terms.

To develop the glossaries, the team first collected seven samples of translations from translation agencies contracted by the health plan. The data collection tool provided a definition and part of speech for each term. Terms for which there were inconsistent translations were categorized. Focus groups were held with academic linguists and translators with advanced Spanish language education and extensive experience translating Spanish materials. The objective of the focus groups was to test recommendations for translation conventions to promote consistent or uniform translations of English terms common in health coverage and eligibility materials. The focus group discussions examined several categories of problematic terms and ways these could be handled in translations. Among these were acronyms (not commonly used in the Spanish language) and translation of titles and program names. At the conclusion of the focus groups, participants were asked to submit recommendations for the best way to translate terms with inconsistent translations collected from L.A. Care Health Plan translators. The results of the focus group discussions and an examination of the frequency of use of various terms helped the team discern patterns in the use of terms.

Variation in the translation of professional titles and program or agency names, such as Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) and health maintenance organization (HMO), and frequent use of acronyms in translations are sources of confusion for consumers. The recommendations proposed translating the words represented by the acronym early in the document and where possible including a description of what the acronym represented.

The team also identified a considerable amount of inconsistency in the use of certain health insurance terms. For example, the following terms

______________

1 CAL. HSC. CODE §1367.04 subparagraph (A) of paragraph (1):(i) A health care service plan with an enrollment of 1,000,000 or more shall translate vital documents into the top two languages other than English as determined by the needs assessment as required by this subdivision and any additional languages when 0.75 percent or 15,000 of the enrollee population, whichever number is less.

were used inconsistently to describe the disclosure form used by health plans:

• Combined Evidence of Coverage/Disclosure Form

• Evidence of Coverage (EOC) and Disclosure Information Form

• Evidence of Coverage and Disclosure Form (EOC)

The team recommended that terms be used consistently in English source documents and that the database be used to track language changes as they occur to prompt discussion and standards for how historical terminology should be handled in future translations and renewed printings of translations.

Translation problems also arise with naming conventions that are produced through legislation and policy changes. The team found inconsistent use of program names (Box 3-1) and recommended standard terms.

Many terms used as part of the Medicare program are difficult to understand in English (Box 3-2). Their translation into another language does not inform consumers. The presentation of Medicare products needs to go beyond translation.

Terms used to describe processes, such as completing an advanced directive, disenrollment, and disputed health care services, also need to be described and then translated, Partida said. This also applies to other terms that need to be put into easy to understand language, such as preferred provider organization (PPO) plan, primary care physician (PCP),

BOX 3-1

Examples of Inconsistently Used Program

Names in Health Plan Materials

• State Department of Health Services (SDHS)/California Department of Health Care Services (CDHCS)

• California Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC)

• California Children’s Services (CCS)/California Children Services Program (CCS)

• Medicare Advantage (MA) Plan, also referred to as Medicare Part C or simply Part C

• Healthy Families/Healthy Families Program

• Healthy Kids (State Children’s Health Insurance Program [SCHIP])

SOURCE: Partida, 2011.

BOX 3-2

Difficult-to-Understand Medicare

Program Components (English)

• Part A covers inpatient care in skilled nursing facilities, critical access hospitals, hospitals, hospice, and home health care (hospital insurance, rarely referenced as Part A, also known as “original” or “traditional” Medicare). The payment method is also sometimes seen in the title “Fee-for-Service” Medicare.

• Part B is medical insurance to pay for medically necessary services and supplies provided by Medicare. Most require a premium. Covers outpatient care, doctor’s services, physical therapy or occupational therapy, and additional home health care.

• Part C is the combination of Part A and Part B. The main difference is that it is provided through private insurance companies approved by Medicare.

• Part D is stand-alone prescription drug coverage insurance. Most people do have to pay a premium for this coverage. Plans vary and cover different drugs, but all medically necessary drugs are covered.

SOURCE: Partida, 2011.

and primary care provider (PCP doctor). When a term is selected for use by a health plan, it is essential that the term be used consistently.

Other terms raise broader questions. For example, is it necessary to adopt and translate legislatively negotiated descriptions and terms for educational materials, such as creditable prescription drug coverage or appropriately qualified health care professional? This may not be advisable if they do not help the intended audience make health care decisions, Partida concluded.

Effective cross-cultural translations require understanding the context and intended meaning of the source language and the implications for production of an equivalent message in another language. Also relevant is the assumed health literacy of the source and target language audiences. Health literacy is the ability to read, understand, and use health care information to make decisions and follow instructions. It involves comprehension of both the context or setting and the skills that people bring to a health care exchange or as readers of health text. Translation conventions that can be understood by target language audiences are needed for industry language (e.g., member), forms of transacting (e.g., consenting process), health education and promotion, and other important activities related to health encounters. Standards for uniquely American health vocabulary and practices can help promote uniformity

of translations and better enable target readers to associate translations with relevant experiences.

According to Edward Sapir, the distinguished linguist, language is not only a vehicle for the expression of thoughts, perceptions, sentiments, and values characteristic of a community, it also represents a fundamental expression of social identity, “a potent symbol of the social solidarity of those who speak the language.” Shared language helps to promote shared understanding and meaning. In essence, language is more than the sum of its parts; words are entangled with a defined socioeconomic and cultural context. The implications are significant for the translation of health materials developed in English, based on Western concepts of health and shaped by micro- and macroforces that influence health transactions. Developing standards for translation of terms and concepts specific to the American health system can help (1) identify health content with significant differences between English, the source language, and target language and culture; (2) offer guidance on how to achieve shared understanding and meaning across languages; and (3) promote translation consistency.

Information written in clear, easy-to-understand language is essential to access health system benefits and services and quality healthcare. This industry ideal is often difficult to achieve with populations speaking widely diverse languages and associated culturally influenced health beliefs and practices. This diversity of language is likely to grow as globalization of markets, information and communication technology, and international migration trends fuel growth of multicultural and linguistically diverse societies. For California health providers, providing health information in languages other than English is an essential business practice today. This is a practical reality made necessary in a linguistically diverse nation that remains committed to monolingualism. In contrast, plurilingualism in education is a constituent characteristic of the national identity of our European counterparts.

Finally, the field of language translation reflects these two paths to language policy, Partida said. Translation of literature and art emphasize shared understanding and meaning and result in recreated, newly authored products. While health translation practices typically aim to produce linguistic equivalent products that are bound by content in the English original, content that may reflect American health systems values, practices, and vocabulary may have no direct equivalent in the target language. Further, modern medicine and a dynamic health insuring system generate words, concepts, and practices that pose challenges for readers of health materials. Health texts often reflect or include vocabulary referencing; health funding policies or practices determined at the national, state, or organization level; local health practice and conventions; and advances

in the biological sciences and medicine. Except for text devoid of sociocultural context, the translation produced in a target language may not necessarily result in shared understanding and meaning. The language translation task requires identifying representative words or expressions in target languages that may not exist. Use of target language terms with no sociocultural bounding as substitutes or equivalents serves only to confuse. Moreover, opportunities to advance learning of new concepts or health system practices are lost with wide variation or inconsistent translation of English terms, Partida said.

Arthur Culbert, roundtable member, asked Quincy if those who are planning or implementing the state health insurance exchanges are aware of the Consumers Union findings. The findings would be invaluable for planners and policy makers. Quincy said the final reports were going to be issued in the next few weeks. The results have been shared with the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The first two studies were designed to help them with their work. Quincy plans to actively disseminate the findings in the fall of 2011.

Cindy Brach, roundtable member, asked if Consumers Union would consider rating health plans in terms of how intelligible their materials are, such as the coverage benefits information and membership materials. Brach suggested that Consumers Union involvement could serve a public education function, raise the awareness of health plans, and play a role in accountability that could help spur improvement. Quincy replied that she could not speak for her organization, but that such a task would be consistent with the mission of Consumers Union. Funding such an effort may be an issue because it is expensive to develop measures that are both meaningful to consumers and that can be trusted because they are backed up by credible data. Partida added that her work with L.A. Care Health Plan illustrated the need to examine both terms used by the state in their public programs (e.g., Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program [CHIP]) and the vocabulary unique to the health plans.

Ruth Parker, roundtable member, asked Quincy whether issues related to consumer trust of health insurers arose in Consumers Unions research, and if so, whether there were insights into what can be done to repair broken trust. Quincy said that some of the issues that have contributed to distrust will be alleviated with the full implementation of health reform; for example, coverage rescissions are prohibited and medical underwriting will no longer be allowed in 2014. Trust will likely be enhanced when plans are simplified and plan terms are easier to understand. Exchanges should vet health plans with trust considerations in mind. There can be

no hidden traps for consumers; if such loopholes persist, the relationship between the plan and the consumer is damaged and difficult to mend. It would be helpful to understand how consumers react to mechanisms such as the seal of approval for plans used in Massachusetts. The results of consumer testing could be very informative, Quincy said.

Andrew Pleasant, roundtable member, concluded from Quincy’s presentation that people use a mental map of health insurance that centers on providing financial reimbursement for sick care. He wondered if the model could be reframed to focus on reimbursement mechanisms for prevention. He wondered if consumers would place a higher value on health insurance if it emphasized the receipt of benefits when the individual is well. Quincy suggested that this perspective changes the equation into “What can purchasing this health plan do for me?” as opposed to “What do I have to pay if I buy this product?” Health insurance information is currently presented with a focus on the consumers need to pay a premium, a deductible, co-payments, and coinsurance. Consumers then have to decide whether the benefits outweigh the plan’s cost. If consumers were approached with the notion that if they paid the premium, they would receive well care, in addition to coverage for unexpected, catastrophic illness, they may feel more positively about the plan.

Margaret Loveland, roundtable member, noted that people tend to dread what they do not understand, and what they do not understand, they do not trust. She observed that consumers now have many choices of health care coverage. She asked how consumers (and health insurance plans) feel about simplifying health plans and perhaps reducing the number of choices. Susan Pisano of America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) indicated that health plans viewed the prospect of simplification very positively. However, considerable work is needed to simplify health insurance language so consumers can understand the plan’s terms, she said. Health plans are actively addressing health literacy concerns. When beneficiaries trust their insurer and understand their benefits, they are more satisfied, make better use of their benefits, and are healthier.

Moderator and roundtable chair George Isham added that in the current insurance market, health plans create products for different groups, such as unions or large employers. In an environment where there are different purchasers, the benefits, services, and price are tailored to suit the needs of the purchaser. This partially explains today’s variety in plan benefits and structure. State insurance exchanges, which will offer individual and small group products, are debating how much variation to allow in the products offered. It is likely that different products and approaches may suit the unique markets that exist across the country. Quincy added that purchasers such as unions or large employers do tailor their health plan designs for their employees or members. However, the employees

or members generally end up being offered one or a few plan options, making it fairly easy to choose among them. Isham noted that while states will follow the guidance available from the federal government, they may come to different decisions about plan offerings.

Brach asked Partida if federal legislation exists, or is emerging, to regulate language threshold requirements for translation and interpretation services. Many state Medicaid programs must provide language assistance for speakers of languages other than English if the population of speakers of that language exceeds a certain threshold within a community or market area. Brach asked if there are lessons from Medicaid, CHIP, or other programs that would inform the health insurance exchanges. Partida was not aware of any federal legislation that included such requirements, but mentioned that California had required translation services for 10 languages, but that the requirement has been reduced to five languages, in part, because of the difficulty of assuring the effectiveness of translation. There are issues related to both the quality of translation and the literacy of the target population. Providing written materials in the native language of immigrant populations that are illiterate, or marginally literate, is not helpful. There are many Spanish speakers who have no formal knowledge of their Spanish and speak English very marginally. The quality of translations is also an issue given the diversity found within any particular language, Partida said.

Roundtable member Will Ross asked Quincy whether the nation will be able to fulfill its objective of having 30 million more people insured by 2014, given the constraints on Medicaid funding and the cognitive difficulties that consumers have making health insurance choices. Quincy stated that experience with programs such as Medicare Part D, the prescription drug benefit for seniors, suggests that people who are uninsured will gain insurance. What is less certain is whether individuals’ choice of an insurance plan will be an informed choice. The ability of consumers to make informed choices will depend on whether they are provided with an appropriate set of tools and assistance they need. One of the benefits of having exchanges implemented in a tailored fashion across 50 states is the ability to compare and contrast the experiences of those exchanges and to observe which programs are succeeding. Isham questioned whether any differences between exchanges would inform change. There are differences in state Medicaid programs, but these differences do not generally contribute to reform. He added that states lacking a robust Medicaid program have difficulty making improvements. Quincy suggested that states have learned from each others Medicaid programs, with “best practices” becoming more prevalent—such as moves toward administrative simplicity, reducing stigma, and improved outreach programs.

Isham asked the panel if mechanisms needed to be developed to

ensure that improvements are made. Quincy stated that goals should be established for exchanges, and progress toward those goals should be measured over time.

Linda Harris, roundtable member, asked Quincy what role Consumers Union might play in helping consumers purchase health insurance through the state health insurance exchanges. Quincy stated that the primary and traditional role of Consumers Union is to be a trusted source of information. The ability to provide comprehensive information depends on the availability of financial support. There is considerable interest in improving consumers’ choices, and Consumers Union is actively exploring the possibility of partnering with other entities to provide information that can be trusted.

Pleasant asked Partida if the glossary of health insurance related terms she described in her presentation is publicly available. Partida replied that the L.A. Care Health Plan will be making the glossary publicly available.

An audience member, Zadkiel Elder, an economist from the Department of Labor, asked the panel whether health plans could be incentivized to simplify health insurance options. Quincy stated that based on the experience of the Massachusetts exchange, it is possible to simplify plans. That exchange placed the insurance products into three actuarial value tiers. Health plans then provided within a tier all the plans offered that provided a similar level of financial protection. However, consumers had difficulties comparing plans because, although they had similar levels of financial protection, they still had very different underlying provisions. The Massachusetts exchange decided to move away from the actuarial value tiers and develop more standardized plan designs. In this case, consumer testing was instrumental in the move toward standardization, Quincy said.

One study, published concurrently with the Massachusetts move to simplify choices, examined how plans that were in the same actuarial value tier dealt with claims for a hypothetical case of breast cancer (Pollitz et al., 2009). The plans within the tier had similar deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums, but because of exceptions associated with these cost-sharing provisions, the patient’s out-of-pocket costs for the hypothetical disease varied by tens of thousands of dollars.

Audience member Angele White, a health educator, described how in her work with clients who are uninsured or underinsured, there is often confusion about health plan coverage. An individual may select a plan only to learn later that the plan does not cover their condition or fit their circumstance. Once covered, it is often difficult to switch plans to one that is more suitable. A client who is pregnant and learns that her plan does not cover the full spectrum of neonatal care may not be able to switch in

time to get the coverage she needs. White asked Quincy if some of the lessons learned from research conducted concerning private insurance plans was applicable to public insurance plan enrollment. Quincy said that the same general rules apply. However, it is helpful to tailor communications to clients according to their level of health insurance literacy. Quincy advocates for a measure of health insurance literacy and better health insurance education.

White asked Partida about incorporating cultural and ethnic norms into translations. White found that her clients from different African communities vary in their interpretation of information. Partida described how her team attempted to find common vocabulary across the different Spanish-language countries studied while working on the glossary of health insurance terms. They found that cultural differences in interpretation diminished with time spent in the United States. Immigrants often live in proximity to people from other Spanish-language countries, and they are also being influenced by the English language spoken around them. Partida discussed the difficulty of developing materials within a language that addresses cultural differences. Attempts have to be made to organize and simplify information to reach a broad audience. If insurance terms are explained clearly, simply, and are consistently used, people can begin to learn them.

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 2009. 4th ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. http://www.thefreedictionary.com/ (accessed September 21, 2011).

Colina, S. 1997. Contrastive rhetoric and text-typological conventions in translation teaching. Target 9:353-371.

Colina, S. 1999. Transfer and unwarranted transcoding in the acquisition of translational competence: An empirical investigation, In Translation and the (re)location of meaning, edited by J. Vandaele. Selected Papers of the CERA Research Seminars in Translation Studies. Leuven. Pp. 375-391.

Consumers Union and People Talk Research. 2010. Early consumer testing of new health insurance disclosure forms. http://prescriptionforchange.org/pdf/CU_Consumer_Testing_Report_Dec_2010.pdf (accessed September 2011).

Gasser, M. 2006. How language works: The cognitive science of linguistics. http://www.indiana.edu/~hlw/ (accessed September 21, 2011).

Kleimann Group and Consumers Union. 2011a. Early consumer testing of the coverage facts label: A new way of comparing health insurance. http://prescriptionforchange.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/A_New_Way_of_Comparing_Health_Insurance.pdf (accessed August 2011).

Kleimann Group and Consumers Union. 2011b. Early consumer testing of actuarial value concepts. http://prescriptionforchange.org/document/report-early-consumer-testing-of-actuarial-value-concepts (accessed September 2011).

Partida, Y. 2011. The challenge of health insurance language or communication with vulnerable populations. PowerPoint presentation at the Institute of Medicine workshop on Facilitating State Health Exchange Communication Through the Use of Health Literate Practices, Washington, DC.

Pinker, S. 1994. The language instinct: How the mind creates language. New York: HarperCollins.

Pollitz, K., E. Bangit, J. Libster, S. Lewis, and N. Johnston. 2009. Coverage when it counts: How much protection does health insurance offer and how can consumers know? Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Quincy, L. 2011. How consumers shop for health insurance: Lessons for exchange designers. PowerPoint presentation at the Institute of Medicine workshop on Facilitating State Health Exchange Communication Through the Use of Health Literate Practices, Washington, DC.