The dramatic changes going on in health care today will have an equally dramatic effect on allied health, and these effects will play out directly in the ways care is delivered in communities and to individual patients. Three speakers at the workshop discussed these real-world effects in the context of health care reform. Cathy Martin, director of Workforce for the California Hospital Association (CHA), talked about a survey of allied health workforce needs that coincided with the passage of health care reform legislation. Mary Anne Kelly, vice president of the Metropolitan Chicago Healthcare Council (MCHC), described what health care reform will mean for metropolitan Chicago. Finally, Jason Patnosh, associate vice president and national director of Community HealthCorps for the National Association of Community Health Centers, Inc. (NACHC), explored how the expansion of health care coverage will affect community health centers.

AN ALLIED HEALTH WORKFORCE SURVEY IN CALIFORNIA

In 2007 the CHA created the Healthcare Workforce Coalition to create and lead a statewide, coordinated effort to develop and implement strategic, long-term solutions to the shortage of nonnursing allied health professionals. At the time, before the economic recession that began in 2008, the CHA was worried about increasing retirements among allied health workers and an aging population, said Martin. Since then the economy has changed dramatically, but concerns about the allied health workforce remain, especially as the California budget crisis has reduced funding for educational institutions that educate health care workers.

Martin said the Healthcare Workforce Coalition conducted a survey in 2007 of hospitals and found that imaging, laboratory, and pharmacy personnel were among the top positions that affect hospital efficiencies and access to care when vacancies exist. In 2009 the CHA decided to conduct a follow-up survey to understand how the economy was affecting demand for allied health professionals currently and to assess hospital concerns regarding workforce in the future. The survey was distributed to 200 hospitals, and 125 responded. The response was strongest from northern and central California, yet was generally representative of the CHA membership overall. Martin noted that rural hospitals were slightly overrepresented, which was a positive because that “was a critical component that we wanted to capture.”

The survey asked about 14 occupations chosen by the CHA Workforce Committee:

1. Clinical laboratory scientist

2. Medical laboratory technician

3. Radiologic technologist

4. CT technologist

5. PET technologist

6. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology technologist

7. MRI technologist

8. Ultrasound technologist

9. Nuclear medicine technologist

10. Pharmacist

11. Pharmacy technician

12. Physical therapist

13. Physical therapy assistant

14. Respiratory therapist

Not all of these occupations would be classified as allied health (e.g., pharmacists), but the survey results nevertheless provide useful and valuable information about allied health professionals.

The survey showed that respiratory therapists are the largest of the 14 occupations at the hospitals surveyed. The top five occupations—respiratory therapists, pharmacists, pharmacist technicians, radiological technologists, and clinical laboratory scientists—make up 76 percent of the total full-time equivalent (FTE) positions reported by the survey respondents.

The occupation with the highest vacancy rate was physical therapist. Smaller hospitals had higher vacancy rates than larger hospitals. Also, rural communities are in greater need of physical therapists than urban communities, Martin said. “It’s tough for students to get education and training in this area in rural communities, and it’s tough to attract them to practice

in those communities. It is something that we definitely see on the horizon and is a concern for us, especially with the aging population.”

One survey question asked about the impact that vacancies have on access to care and hospital efficiencies, with a rating of 1 denoting no impact and 5 the greatest impact. The profession with the highest impact score was pharmacists, followed by physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and clinical laboratory scientists.

Clinical laboratory scientists had the highest average age across all of the selected surveyed professions. Using 62 as the age of retirement, the survey showed that 844 clinical laboratory scientists are eligible to retire between 2010 and 2015 in the 125 hospitals that responded. Yet programs in California currently produce only 100 to 125 clinical laboratory scientists per year. “This is important, because this does not include outpatient settings [or] public health,” said Martin. Also, becoming a clinical laboratory scientist requires a bachelor’s degree and an additional year of training. “These folks take a long time to train, and we need many of them.”

Radiological technologist is fourth on the list of pending retirements, which would seem to indicate that training more of these individuals is less important than for occupations higher on the list. But hospitals strongly refute that conclusion, said Martin. The supply-and-demand data for radiological technologists is misleading. Although we produce more than demand suggests is needed, radiological technologists are not static in their practice. “Imaging department directors take their best and most promising rad tech, and train them to be their next MRI, cardiovascular tech, or what have you, because those are where your real critical needs are, in the subspecialties,” said Martin. “This is where bringing employers to the table is critical when we have these discussions because they are the ones who have to get these folks into the positions, and they are the ones struggling to find them.”

Health care reform legislation was passed in the middle of the 2010 survey. If health care reform increases the need for primary care professionals, it may be necessary to expand the definition of primary care, Martin said. Chronic care management and community-based care also may grow in importance, as well as the need for health information technology (HIT) skills among clinical workers and HIT workers who understand clinical workflows. Other workforce needs cited by hospitals responding to the survey were for direct care workers, including home health aides and long-term-care professionals, and social and health case management for behavioral health patients.

The CHA plans to continue to use information generated by the survey to inform regional and statewide efforts, Martin said. It also will participate in the planning and implementation stage of the California Workforce Investment Board’s Health Workforce Development Council. It will develop

and maintain a repository of promising practices on CHA’s website. And it will continue to coordinate and collaborate with other statewide efforts to ensure that strategies are responsive to industry’s needs.

NEW AND CHANGING NEEDS IN CHICAGO

Chicago provides an excellent example of the changes being created not just by health care reform but also by education reform, said Kelly.

Information Technology in Health Care Reform

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 20091 drives electronic health record adoption in several ways. First, HITECH calls for the formation of health information exchanges (HIEs) at the local, state, and national level. The major functions of HIEs are to enable the sharing of clinical information; to coordinate care, quality, and health status reporting; and to promote the use of shared platforms. The patient is at the center of the HIE, said Kelly, not the technology. “It’s about building the social capital to create a robust information exchange that will lead to quality outcomes and improved patient care. The technology is the underpinning to achieve that.”

The HITECH Act calls for the “meaningful use,” as the act puts it, of patient information through electronic medical records. As David Blumenthal, then the national coordinator for Health Information Technology for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said in 2009, “We recognize that better health care does not come solely from the adoption of technology itself but through the ongoing private and secure exchange and use of health information to provide the best possible information at the point of patient care” (HHS, 2009). This new capability in turn requires workforce development to make this happen, said Kelly.

A health information exchange connects many stakeholders, including hospitals, physician offices, laboratories, pharmacies, long-term care providers, imaging centers, other HIEs, behavioral health providers, and consumers to enable the meaningful exchange of information. As an example, Kelly cited the exchange of clinical data in the emergency room. If someone is in an accident and is taken to a hospital where that person does not normally receive care, with access to an HIE the emergency room physician and staff can access medical information under a secure framework. A second example Kelly cited is public health data reporting to improve population health.

![]()

1 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, Public Law 5, 111th Cong., 1st sess. (February 17, 2009), §§ 13001 et seq.

A second component of the HITECH Act is the creation of regional extension centers (RECs) to provide support to primary care providers in small practice settings as they move toward the goal of meaningful use. The MCHC serves as a satellite office of the Illinois Health Information Technology Regional Extension Center to such services as practice assessments, vendor selection, purchase facilitation, workflow redesign and preparedness, quality reporting assistance, HIE interoperability, and privacy and security considerations.

A third component of the HITECH Act is developing the workforce to achieve and support electronic health records and their meaningful use. This includes such means as curriculum development centers, a community college consortium, competency exams for individuals, and university-based training. For example, the community college consortium trains people in 3- to 6-month certification programs to provide assistance to physicians and to other practice settings in implementing electronic medical records. Careers in this area include implementation support specialists, practice workflow specialists, information management design specialists, clinical consultants, and implementation managers. “These are going to be the first responders to this large-scale implementation of HIT,” said Kelly. More long-term careers for health care delivery and public health sites include clinical IT leaders, technical and software support, trainers, HIE specialists, and privacy and security specialists. Positions for health care and public health informaticians include research and development scientists, programmers and software engineers, and subspecialists in such fields as ethics, human factors interfaces, and industrial/systems engineering.

To fill these positions, health information technology education must be offered to the current workforce and incorporated into the curricula of all health professions. “Work is going to change,” said Kelly. “If we don’t get the workflow issues right, we are not going to be moving this forward successfully.”

Education Reform

Education reform will have a big effect on the health professions, said Kelly. Although Illinois was not selected for a Race to the Top award, the process of applying for the award led to considerable planning among a wide group of stakeholders who remain committed to moving forward. The initiative to reform science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education has been led by the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity, with strong support from the Department of Education and higher education. Illinois is scaling up its programs of study around STEM education, and health care is at the top of the list.

Several pilot projects under way are focused on health care as a career

cluster. To accomplish its goals, Illinois envisions the creation of a health education learning exchange that would enable the sharing of resources, curricula, space, and laboratories. Participants in the education exchange would include integrated education systems, employers, unions, and professional associations, with the health professions providing advice on curricula. “Educators [could] pull together and not reinvent the wheel for schools of allied health,” said Kelly.

Finally, Kelly briefly described a school that is a microcosm of education reform. Instituto del Progreso Latino is a community-based organization in metropolitan Chicago that has been working for 35 years in adult education. Upon successfully receiving approval to create a charter high school, in September 2010 the Instituto opened the Instituto Health Sciences Career Academy, a 600-student high school focused on career education and college readiness in the health sciences. “Just in the first 163 days of the school, these children have come so far in their understanding of the world that’s available to them in health careers because we’ve really focused this year on career exploration,” Kelly observed.

COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS AND THE ALLIED HEALTH WORKFORCE

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) were founded more than 40 years ago in Boston and Mt. Bayou, Mississippi, by Jack Geiger and Count Gibson in collaboration with the federal Office of Economic Opportunity. They are consumer oriented and directed, are located in medically underserved areas, provide primary and preventive health care, and are open to all regardless of ability to pay. Patnosh noted that according to estimates performed by the NACHC, FQHCs see more than 22 million patients annually across 1,200 grantees and more than 8,000 locations.

The NACHC was founded a few years later to serve as the voice for health centers, provide technical assistance and support, and develop programs for FQHCs, said Patnosh. Its overall mission is to promote the provision of high-quality, comprehensive, and affordable health care that is coordinated, culturally and linguistically competent, and community directed for all medically underserved people.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)2 provides $11 billion in dedicated funding for health center operations and capital for FY 2011–FY 2015. This amount includes $9.5 billion to support health center operations and $1.5 billion for capital needs. These funds are meant to serve additional patients by expanding current service capacity, including

![]()

2 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 148, 111th Cong., 2nd sess. (March 23, 2010).

adding providers and staff and increasing hours of operation. Increased funding also provides for new or expanded oral health, behavioral health, pharmacy, and enabling services.

The funding in the ACA was enough to increase the number of patients seen in community health centers to 40 million. Many of these additional people seen would be among the 32 million uninsured individuals in the United States. However, in the FY 2011 budget deal, funding for FQHCs was reduced by $600 million, affecting the ability of FQHCs to reach this number.

“Where are these patients going to go?” asked Patnosh. “If you’re working in the hospitals, they’ll still be showing up to the emergency rooms. If you’re in the community health centers, they are still going to be showing up. We’re still going to be seeing them. [But] how far can we extend the already stretched load on the health care system?”

Many allied health professionals work in FQHCs, including dental hygienists, medical or dental assistants, health information technologists, health care administrators, medical coders, pharmacy technicians, phlebotomists, and community health workers. Some of these people can climb a career ladder or shift professions within allied health to fill needed jobs, such as a health information technologist who takes on other administrative roles. Also, health care institutions can compete among themselves for people in these positions, which raises the questions of whether FQHCs can keep allied health workers as they receive additional training.

Examples of Identification and Pipeline Programs

Patnosh briefly described several programs that serve as models for identifying, training, and retaining allied health workers.

The World Academy for Total Community Health in Brownsville, New York, has the mission of preparing high school students to make healthy choices, lead healthy lives, and advocate for the total health of their families, their communities, their nation, and ultimately their world (Brownsville Multi-Service Family Health Center, 2011). It exposes students to all aspects of the health care field and to the variety of career options the industry offers, creates a socially supportive learning environment, and offers an academically rigorous curriculum that prepares students for higher education. Lead partners are the Brownsville Multi-Service Family Health Center (an FQHC), the Long Island University School of Nursing, and the Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education.

The Central Valley Health Network (2011), which is a network of FQHCs in the Central Valley in Sacramento, holds an annual conference for 400 to 500 local youth that highlights leadership and careers in health care. The biggest challenge in the Central Valley is not necessarily to get

individuals into a health career but keeping them in the Central Valley. “They are trying to figure out how do they develop their own and keep their kids there,” said Patnosh.

The Area Health Education Centers are creating programs nationwide for youth as early as first graders to teach healthy lifestyles and spark interest in health careers (HRSA, 2011a).

High school dropout rates are critically important, Patnosh emphasized. “If there is any position in your agency or in a health care institution that does not require a high school degree, I would be shocked,” he said. With dropout rates of 30 percent or more in some high schools, workforce development inevitably will be a challenge.

Community HealthCorps is one of NACHC’s signature programs (Community HealthCorps, 2011). Its mission is to improve health care access and enhance workforce development for community health centers through national service programs. It is the largest AmeriCorps program in the country that is based in health care, with more than 500 full-time AmeriCorps members coming through the project every year. Many of them are in a gap year between an undergraduate degree and graduate school or medical school. But others have only a high school diploma or GED. By serving, they receive a $5,350 scholarship, and many 4-year degree schools are starting to match AmeriCorps scholarship money. More than 250 service locations now host AmeriCorps members.

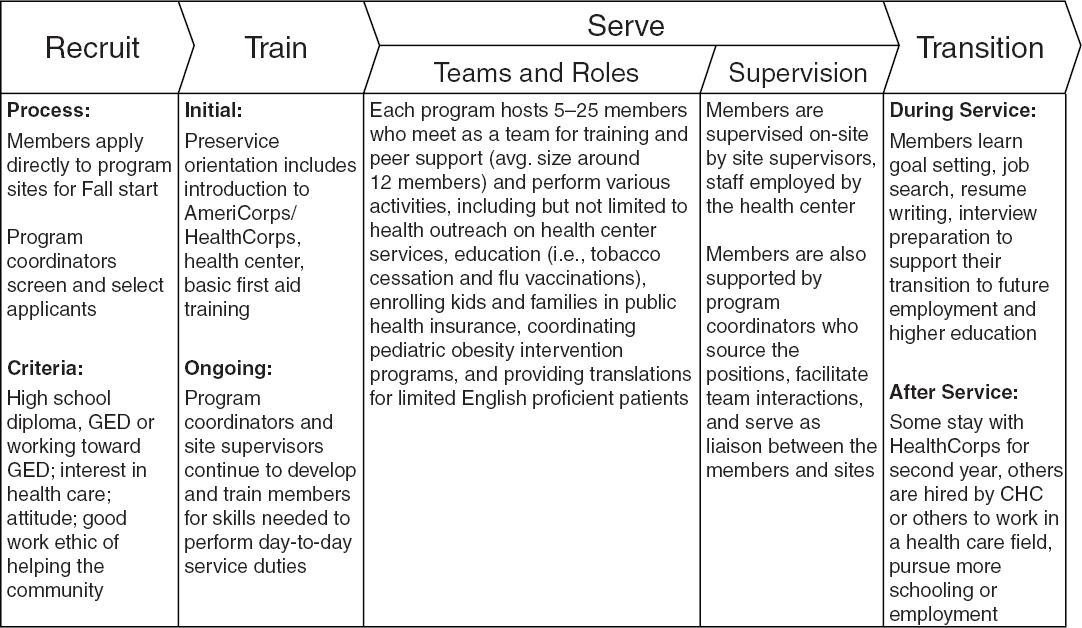

Community HealthCorps has a standardized program design that works, said Patnosh (see Figure 5-1). Its benefits include a more skilled workforce, increased engagement of community volunteers, greater advocacy for community residents and community health issues, increased third-party health insurance and other revenues, and increased funding diversification. Participants benefit through improved understanding of community health delivery, improved interest in high-need health careers, job skills, and workplace experiences that lead to living wage career opportunities, reduced debt burden, encouragement for further education, and increased self-efficacy.

In 2009–2010, Community HealthCorps served approximately 1.2 million people who lacked access and inadequately used health services (NACHC, 2011). About $11 million was invested in the program—$6 million from federal sources and $5 million from local matches. The value of the service that members provided is estimated at $14.4 million, in addition to the $2 million in educational scholarships they earned. This represents a 145 percent return on investment, along with healthier children and families and the development of the workforce.

Health care reform will require a well-trained workforce to deliver more effective care. A major challenge, Patnosh concluded, is forming partnerships among academic institutions, hospitals, and community public

FIGURE 5-1 Community HealthCorps Program design.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Jason Patnosh, National Association of Community Health Centers.

health departments to put the patient at the center of care wherever it is delivered.

In response to a question about integrating behavioral health workers into health care settings, Patnosh emphasized the importance of both reimbursement systems and innovation. Health care is a very regimented system that can be difficult to change. Change requires innovation, and one innovation that can help move the needle is the concept of team care. However, team care needs to begin not at the level of delivery but at the level of schooling. Individuals need to learn to understand the roles of different positions within the care team.

Kelly added that a growing issue in Chicago is the presence of comorbidities when a patient comes to a caregiver. A patient may have a medical condition, but a behavioral health issue exists as well, and a health care provider may not be equipped to deal with that comorbidity. On that point, Patnosh observed that the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is particularly experienced at dealing with multiple health issues, including behavioral health issues. The VHA also instituted the use of electronic medical records very early, which has helped it integrate primary care and

mental health. In addition, as a workshop participant pointed out, allied health workers such as occupational therapists are positioned in the gap between physical health and behavioral health.

Nooney called attention to the fact that 62 is a young age for retirement, which raises the issue of how to retool an aging workforce as health care needs evolve. As one example, her hospital has been working to reduce the physical demands of nursing for older workers. If people choose to work past what was once considered retirement age—and many will, for economic reasons—how can they be used most effectively, she asked. Kelly observed that older workers also could play a valuable role in education, but programs need to be established to use their skills and experience for that purpose. Patnosh added that programs are starting to appear both within health care and elsewhere to bring older workers in as “encore fellows” where they contribute in a meaningful way to ongoing projects. “We have seniors within our AmeriCorps project, and starting this year… anybody 55 years or older can do a year of AmeriCorps and give that educational award to a child or grandchild.” Older people tend to have specific reasons for getting involved and are often passionate about their work, he said.