The Immigration Enforcement System

This chapter describes the U.S. immigration enforcement system. Although its functions and activities are administered separately by various components of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the U.S. Department Justice (DOJ), in conjunction with the federal courts, it is best understood as a single system, albeit one that is highly fragmented and disjointed. The committee recognized at the outset that it would need to understand and describe the system as a whole in order to address its charge of improving budgeting for DOJ’s immigration enforcement functions.

Our description of U.S. immigration enforcement is intended to capture not only the way the enforcement system was designed to function, but also how it actually operates. In 2010 and 2011, committee members and staff visited the El Paso, Tucson, and San Diego border sectors, where they interviewed (among others) officials from DOJ, DHS, and state and local law enforcement; public defenders; federal district, magistrate, and immigration court judges; and immigration advocates. The information and insights from those interviews are reflected throughout this chapter. Although the resulting portrait is hardly definitive, it identifies the characteristics of the system most salient for budgeting.

The committee also sought to use data provided by two DHS components—the Office of Immigration Statistics and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to create individual case histories for apprehended immigrants moving through different components of the immigration enforcement system; unfortunately, the available data did not

allow us to do this. In the course of working with these data, however, we discovered significant differences between the data that were given to the committee and official (and published and commonly used) data on apprehensions. Although this chapter makes extensive use of official data, their limitations (discussed below) should be kept in mind.

The number of would-be migrants who seek entry to the United States (as to other wealthy destination countries), whether on a temporary or permanent basis, far exceeds the number of visas that Congress has authorized. This gap leads inevitably to unauthorized flows and visa overstays and necessitates an effective immigration enforcement system. Immigration enforcement activities, however, require agents not only to prevent and remove unauthorized immigrants, but also to admit and facilitate legal migration flows for tourism, education, business, and other activities in the United States.

The U.S. immigration system is highly complex. It involves scores of legal visa categories, dozens of grounds for removal, and various opportunities for unauthorized immigrants to seek discretionary relief from enforcement actions in administrative and judicial forums. At most points in the enforcement system, moreover, agency personnel and officials can exercise discretion in the use of their authority.

Today’s immigration enforcement system reflects important policy innovations, decisions, institutional changes, and political events that have developed over almost one-half century, dating back to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which ushered in the modern era of immigration law and policy. Appendix A provides a timeline of the post- 1965 statutory, policy, and administrative changes that are most relevant to current enforcement challenges and to the budget-relevant interactions between DOJ and (since 2003) DHS. More recently, the aftermath of the events of 9/11 and their interaction with changes in the 1996 immigration law have been of overarching importance in understanding today’s immigration policy and operational landscape.

Because the 9/11 hijackers had entered the country with properly issued visas, immigration issues became irrevocably linked with antiterrorism and national security. The calls for secure borders were widespread and urgent, and immigration enforcement became understood as a front-line measure that had to be strengthened to protect the country. Thus, immigration functions were largely incorporated in the new cabinet agency, DHS, border-related resources grew dramatically, and the interoperability of federal databases—including data collected and managed by immigration agencies—became broadly available for immigra-

tion enforcement purposes, including by state and local law enforcement agencies.

The substantial resources and new policy importance of immigration enforcement followed statutory changes in immigration law that date back to 1988. They culminated in new provisions in the 1996 legislation that significantly (and retroactively) broadened the grounds for removal of noncitizens who had committed crimes. Tougher laws, combined with record-high levels of unauthorized immigration until the beginning of the severe economic recession in 2008, have resulted in immigration enforcement mandates and needs that are far greater today than those historically characteristic of immigration law and policy.

Today’s immigration enforcement system is commonly understood as having three primary objectives: prevention, removal, and deterrence.

Prevention

The enforcement system seeks, first, to prevent the entry of illegal immigrants. Noncitizens seeking admission to the United States are required to apply abroad for an immigrant or nonimmigrant visa or to obtain a waiver through the Visa Waiver Program: prevention begins during this initial, external application process. Visa applicants are required to visit a U.S. consulate, to be interviewed by a visa officer, and to provide biometric data (fingerprints and a digital photograph) that link the applicant to electronic records that are rechecked when the person arrives in the United States. Travelers from the 36 countries that participate in the Visa Waiver Program are typically exempted from prescreening at a U.S. consulate, but they must apply on-line for authorization to enter the United States, and they must obtain a visa if their planned visit to the United States will exceed 90 days.

An additional round of screening occurs at legal ports of entry, where field operations officers from DHS’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency review travelers’ documents for compliance with regulatory criteria and, in certain cases, recheck travelers’ biometric data, which is added to DHS’s U.S. Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT) system. This review at the port of entry may include more extensive “secondary” inspection of a traveler’s eligibility to enter.

CBP’s Border Patrol also prevents illegal entries between ports of entry by maintaining a mix of physical barriers (including pedestrian fences and vehicle barriers), surveillance technology (including visual and infrared cameras, motion detectors, underground sensors, aircraft, and

radar), and personnel at and near U.S. borders to detect and apprehend immigrants as they attempt to enter illegally or shortly after they have done so.

Removal

The second major goal of immigration enforcement is to remove unauthorized residents and other deportable noncitizens from the country.1 According to the DHS Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2011d), in fiscal 2009 and 2010 approximately 90 percent of deportable immigrants apprehended by DHS were located by the CBP Border Patrol, and the rest were located by ICE.2 Around 97 percent of the deportable immigrants apprehended by the Border Patrol were located in the Southwest sectors of the United States.

Historically, interior enforcement relied primarily on a “task force” model, in which agents from ICE (or its predecessor the Immigration and Naturalization Service [INS]) apprehended suspected unauthorized immigrants through sweeps of agricultural areas and other business establishments suspected of hiring them. In addition to targeting unauthorized workers, ICE began in 2003 to deploy “Fugitive Operations Teams” to locate, arrest, and remove noncitizens who had been charged with immigration violations and then either failed to appear at an immigration hearing after being released on bail or failed to leave the country after being ordered to do so.

More recent efforts to strengthen interior enforcement have emphasized “filters” to screen for potentially removable aliens who come into contact with federal, state, or local criminal justice systems. ICE’s Criminal Alien Program (CAP),3 which evolved out of two INS programs from

![]()

1U.S. immigration law establishes several conditions that make aliens inadmissible and subject to exclusion at a port of entry, including because they are likely to become a public charge or because they have committed certain types of crimes, as well as conditions that make them deportable, including because they are in the country illegally. Several classes of noncitizens may be subject to deportation even though they entered the country legally, including students, temporary workers, and other legal immigrants who violate the terms of their visas and lawful permanent residents who commit “aggravated felonies” or other crimes that make them ineligible for U.S. residence. In 1996, the exclusion and deportation processes were combined into a single “removal” procedure (see discussion below).

2CBP apprehensions do not include apprehensions by CBP agents at ports of entry, and deportable aliens located by ICE do not include arrests under the 287(g) program (which deputizes local officials as federal immigration agents; see below) or other arrests of deportable aliens by federal, state, or local law enforcement agencies.

3CAP issued 164,296 charging documents as an initial step for formal removal in 2007, 221,085 in 2008, 232,796 in 2009, and 223,217 in 2010 (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2008, 2009, 2010b, 2011b).

the 1980s, operates in jails and prisons to check the immigration status of arrestees as they are booked into the facilities and to ensure that removable aliens are transferred to ICE custody for removal when they complete their sentences.4

The Bush and Obama Administrations have instituted two additional jail-screening programs: section 287(g) and Secure Communities. Under the section 287(g) program, established in 1996 but primarily implemented since 2005, state and local law enforcement agents receive ICE training and supervision to conduct CAP-type screening in jails. About 10 percent of 287(g) program activities consist of task force enforcement through traffic stops or other community interventions instead of, or in addition to, jail screening.5 Under the Secure Communities Program, established in 2008 and slated to expand to every state and local jail in the country by 2013, arrestees’ fingerprint data are automatically checked against national immigration databases as part of the booking process. Centralized ICE screeners forward information about potentially removable aliens to local ICE officials, who may contact local jails to take custody of and deport arrestees following completion of their jail sentences.6 In 2011, DHS announced that it did not need the approval of state governors to operate the program in their states (Bennett, 2011).

Between 30 to 50 percent of the unauthorized immigrants in the United States are estimated to be visa overstayers (Pew Hispanic Center, 2006), although ICE has allocated only about 3 percent of its investigative work hours to this category of illegal residents. Approximately 8,100 overstayers were arrested from fiscal 2006 through 2010. In the absence of a comprehensive biometric entry and exit system for identifying overstays, DHS’s efforts to identify and report on overstays have been hindered by unreliable data (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2011). Even if a good entry-exit system were in place, however, the pursuit of individual overstayers may still be an inefficient use of ICE resources in comparison with, for example, denying unauthorized immigrants access to the labor

![]()

4A federal statute generally requires undocumented residents to complete their criminal sentences prior to being deported (Schuck, 2011).

5As of October 2010, ICE had 287(g) agreements with 69 state and local law enforcement agencies (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2010a). Although this number represents a relatively small share of the more than 3,000 law enforcement jurisdictions in the country, it includes a number of large jurisdictions such as the city of Los Angeles and Harris County (Houston), Texas.

6In fiscal 2010, 49,432 aliens were removed based on matches made through Secure Communities, up from 14,353 in fiscal 2009. As of June 2011, the Secure Communities identification system covered 74.7 percent of the foreign-born noncitizen population in the United States, an increase from 31 percent in fiscal 2009 (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2011c).

market through a mandatory employer verification system (see discussion below).

Deterrence

The goal of prevention and removal policies is to raise the cost of unauthorized migration and the probability of apprehension at the border or in the U.S. interior, in order to reduce the expected benefits (or increase the expected costs) of such migration. These policies thereby contribute to a third enforcement goal: deterrence of potential illegal entrants and overstays. The immigration system promotes deterrence though a “consequence delivery system” (see, e.g., Fisher, 2011). Rather than simply returning unauthorized immigrants to their countries of origin, this policy seeks to subject immigrants to additional immigration penalties, criminal charges, or even time in jail or an immigrant detention facility. In the case of unauthorized Mexican immigrants, the policy also may include taking them to remote locations in Mexico, making it more costly to make a new attempt at illegal entry. As noted in Chapter 3, although increased border enforcement has successfully increased border crossing costs, the deterrent effects have been small. The consensus appears to be that, as long as migrants can quickly find employment, they are able to finance more costly crossings by borrowing.

Hence, an additional strategy for deterring illegal migration has been to more effectively block unauthorized immigrants’ access to labor markets and federal and state welfare programs, further reducing the benefits of illegal migration. Employers are required to confirm the identity and eligibility of new workers by checking their driver’s licenses and Social Security cards or other documents and (in some cases) checking the information against federal databases of legal workers. ICE agents audit employer records to verify that employers have made a good-faith effort to comply with these requirements: employers who knowingly hire or employ unauthorized immigrants may be subject to civil fines, and employers accused of a pattern or practice of employing unauthorized workers may face criminal charges.

Worksite enforcement, by and large, does not play a major role in apprehensions. Most recently, under guidelines issued to ICE field offices in 2009, agents have been instructed to pursue evidence against the employers of illegal workers before going after the workers (Thompson, 2009). In addition, since 1996, officials who provide federal welfare benefits and certain state benefits must use DHS’s Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) system to confirm the citizenship or lawful immigration status of recipients and to screen out unauthorized immigrants,

temporary migrants, and recent lawful permanent residents, all of whom are ineligible for most federal welfare benefits.

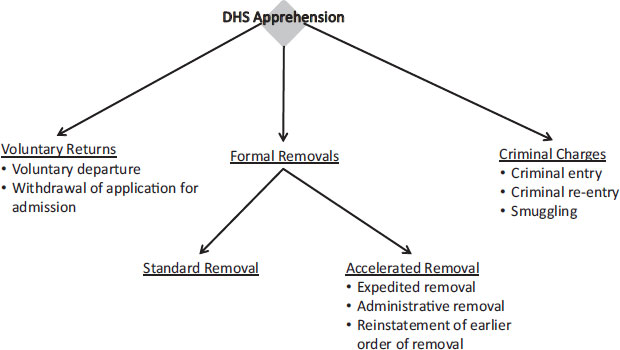

The fundamental question for the immigration enforcement system is how to balance the goals of prevention, removal, and deterrence with procedural guarantees designed to produce fair and accurate decisions and minimize administrative costs. The U.S. system seeks to strike this balance by sorting aliens into one of three main enforcement “pipelines”: see Figure 4-1. These pipelines, in ascending order of seriousness of sanctions, are voluntary return, formal removal, and criminal charges.

1. Under voluntary return, unauthorized immigrants are permitted to return to their country of origin with minimal detention and judicial processing (usually without an appearance before a DOJ immigration judge; see discussion below) and no additional sanctions. The authority to grant voluntary returns rests with DHS and, under certain circumstances, with immigration judges.

2. Formal removal occurs through a removal order issued by an immigration judge (“standard removal”) or by a DHS supervisor (“accelerated removal”). Unauthorized immigrants under formal removal orders are required to leave the country immediately and are subject to additional sanctions related to future entry. Noncitizens may be detained during removal proceedings (at DHS expense7), and in accelerated removal proceedings they usually have to be detained while their removal is pending. Under standard removal proceedings, noncitizens may appear before an immigration judge (with cost implications for DOJ) to petition for relief from removal; under accelerated removal noncitizens typically do not appear before a judge. (For this reason, noncitizens in accelerated removal proceedings usually have short detention periods.) The decision to assign immigrants to standard and accelerated removal proceedings is made by DHS.

3. Immigration-related criminal charges may be brought against unauthorized immigrants, requiring an appearance before a magistrate or district court judge. Criminal charges involve prosecution and detention at DOJ expense. The authority to bring criminal charges rests with DOJ, although misdemeanor cases brought through Operation Streamline (see below) are typically initiated

![]()

7See Schriro (2009) for a comprehensive review and evaluation of the ICE detention system.

by DHS. DHS attorneys also can be deputized by DOJ to prosecute Operation Streamline cases (in which case the costs of prosecution—but not detention—are borne by DHS). Although felony cases can only be prosecuted by DOJ (at DOJ expense), DHS may still play an important role in initiating these cases.

Immigrants apprehended by local law enforcement officials and through jail screening programs—such as CAP, Secure Communities, and 287(g)—will either be subject to some form of accelerated removal, appear in a standard removal hearing before an immigration judge, or be granted voluntary return. The decision about which approach will be taken depends on the nature of their offense and potential eligibility for legal relief.

The committee had hoped to provide a quantitative analysis of flows through the various pipelines. However, as is discussed in Chapter 6, further work is still needed for the production of complete case histories of unauthorized immigrants apprehended by and moving through the enforcement system.

The following sections describe these pipelines in greater detail: who may be placed in each pipeline; how people enter and move through each pipeline, including the type of process they receive; how many unauthorized immigrants fall into each of these categories; and the impact of each enforcement pipeline on DOJ’s resources. Figure 4-1 shows these pipelines

FIGURE 4-1 Enforcement pipelines. See text for discussion.

schematically. Some of the operational information comes from the committee’s two site visits and interviews, discussed in Chapter 1.

Voluntary Returns

Unauthorized immigrants and other potentially removable aliens may be eligible for one of two forms of voluntary return, by withdrawal of their application for admission or by acceptance of voluntary departure. Noncitizens who are denied admission at ports of entry may be granted a withdrawal of application for admission under §235(a)(4) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). Withdrawal of application is granted at the discretion of the DHS sector supervisor: it is usually granted in cases in which a person’s visa is invalid, but the person did not knowingly attempt to enter illegally or engage in visa fraud. People who are permitted to withdraw an application for admission in these cases are required to depart immediately, but are not placed in formal removal proceedings or subject to additional penalties.

Most undocumented immigrants who are potentially subject to removal also may be eligible to receive voluntary departure (commonly referred to as voluntary return) under §240B(a) of the INA, either in lieu of facing formal removal charges or at the conclusion of a removal proceeding and instead of receiving a final order of removal. In practice, voluntary returns are most frequently granted at the discretion of a CBP supervisor to Mexicans who are apprehended within 100 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border. They are returned to a port of entry under CBP supervision and at CBP expense on the same day as their apprehension.8 Voluntary return also may be granted by an immigration judge or DHS sector chief during removal proceedings or after an unauthorized immigrant has been issued an order of removal. In these cases, the people who accept voluntary departure must agree to pay their own return expenses, may be required to post a bond to guarantee their exit, and, when they are in their home country, to visit a U.S. consulate to have their return certified.

To be eligible for voluntary return, immigrants must not have serious criminal records, must not be considered a threat to public safety, and must not already be facing immigration charges.9 In the case of

![]()

8Undocumented immigrants other than Mexicans (“OTMs” in ICE jargon) apprehended by CBP at or near the border are usually placed in formal removal proceedings (see below) and then transported by air to their country of origin.

9Specific requirements are that the person may not previously have been convicted of an aggravated felony; may not have engaged in terrorist activity or been associated with terrorist groups; may not previously have accepted voluntary departure and failed to depart; and, in the past 10 years, may not have failed to appear at a removal hearing after proper notice of removal charges.

withdrawal of application for admission, the unauthorized immigrants must demonstrate the intent and the means to depart immediately and must establish to the satisfaction of the apprehending agents that the withdrawal of application is in the interest of justice.

Voluntary return is akin to a plea bargain in criminal proceedings. An immigrant who is offered voluntary return may reject the offer in favor of formal removal proceedings and thereby have the opportunity to petition for relief from removal and the right to remain in the United States. For an undocumented immigrant, the main advantages of voluntary return are that it does not trigger pre- and post-order detention associated with formal removal, and it does not carry the added penalty of prohibitions on future immigration.

For DHS, voluntary return offers the most efficient mechanism for returning unauthorized immigrants because those who accept it minimize detention and administrative costs. Because those who accept voluntary return from the interior (i.e., not right along the border) agree to pay their own return expenses, they also minimize transportation costs. DHS must weigh these benefits against the risk that the people who accept voluntary return will not actually leave the country since undocumented immigrants who accept voluntary return are seldom supervised during the period allotted for their departure.10 And because voluntary return does not carry additional penalties, it also has no additional deterrent effect beyond the cost to the immigrant of being returned.

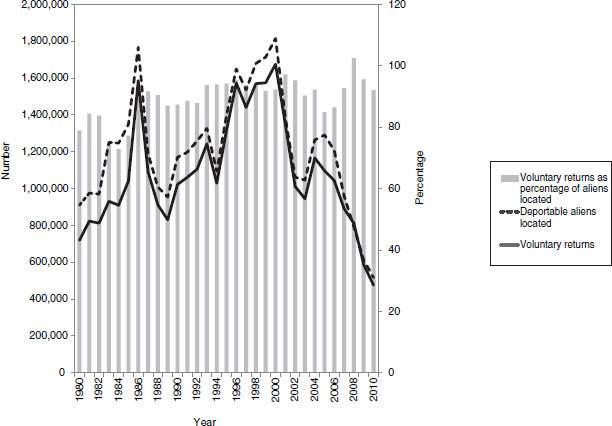

About 90 percent of all of deportable immigrants located since 1980 have been allowed voluntary return: see Figure 4-2.11 Although the absolute number of voluntary returns has fallen sharply from 1.2 million in 2004, more than 91 percent of those apprehended during the 2004-2010 period were still granted voluntary return.

Note that it is possible for voluntary returns in a given year to exceed 100 percent of “aliens located” because DHS’s count of “aliens located” excludes aliens apprehended at ports of entry and aliens apprehended by law enforcement agencies other than DHS, and also because of time lags between aliens’ apprehensions and their formal removal: see Box 4-1.

The high rates of voluntary return seen in Figure 4-2 appear to be at odds with the increased emphasis placed on formal removal and other forms of enhanced consequences for apprehended aliens (see discussion below). This apparent discrepancy is likely a function, in part, of the recentness of CBP’s focus on “consequence delivery” (i.e., the voluntary

![]()

10Unauthorized immigrants who accept voluntary return and fail to depart are subject to formal removal and a civil fine of up to $500 per day, and they are ineligible to be granted voluntary return in the future.

11The voluntary return data include withdrawals of application for admission.

FIGURE 4-2 Deportable aliens located and voluntary returns, 1980-2010.

SOURCE: Data from DHS Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2011d).

return rate may very well be lower in fiscal 2010 and fiscal 2011) and of the undercount of apprehensions in DHS data. However, the committee was unable to resolve its questions about the persistently high rate of voluntary returns.

Formal Removals

Any immigrant who is inadmissible under INA §212(a) or deportable under INA §237(a) is subject to formal removal from the United States12 (see Figure 4-1). Unauthorized immigrants under a final order of removal are ordered to leave the United States, and (at the discretion of an immigration judge or ICE administrator) may be detained until their departure.

![]()

12Removable individuals include, among others, aliens who have been convicted of serious crimes, aggravated felonies, drug offenses, or crimes of moral turpitude; aliens who have engaged in terrorist activities or otherwise threaten U.S. security interests; aliens present in the United States without having been legally admitted or paroled; and those with invalid or expired documents or who have violated the terms of their visas.

BOX 4-1

DHS Data Sourcesa

Data in the DHS Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (Yearbook) for “deportable aliens located” are different from those derived from the DHS public-use files provided to the committee by ICE and CBP. The agency public-use files include an exhaustive record of all immigrants entering the DHS enforcement system in each fiscal year, as well as information about their subsequent release, return, or removal, regardless of whether that occurred in the same fiscal year or later.

A review of data from fiscal 2008 through fiscal 2010 shows that the total number of “deportable aliens located” reported in the Yearbook is about 500,000 less each year than the total number of potentially removable aliens passing through the DHS enforcement system: see the following table. Nearly one-half of this large difference—about 240,000 each year—is attributable to the omission from the Yearbook total of deportable aliens located of those apprehended by CBP Office of Field Operations (OFO). This omission reflects unresolved issues regarding definitions and methods of classification that stem from OFO’s history as the Customs Agency in the Department of the Treasury and the Border Patrol’s history as part of the INS in the DOJ. In addition, the Yearbook data exclude a large number of cases encountered by ICE through referrals from non-DHS sources, including other federal agencies and state and local law enforcement agencies.

In sum, the widely used Yearbook data on deportable aliens located appear to substantially understate the total number of potentially removable undocumented immigrants who are processed through DHS’ enforcement system each year. Given the nature of the omissions, differences in totals for some individual regions may be even larger.b

The differences between data provided to the committee by the DHS component agencies and the data published in the Yearbook raise questions about the completeness of information that government agencies and the public use to estimate immigration flows and, therefore, about the ability of congressional and other policy makers to accurately estimate resource requirements for components of the immigration enforcement system.

Certain people must be detained by DHS during removal proceedings or following a final order of removal prior to their departure.13 Although removal is a civil proceeding and pre- and post-order detention are not explicitly designed as a form of punishment, the threat of detention during and after a removal proceeding may in principle serve as a deterrent to illegal migration. Undocumented immigrants under formal removal orders also face the additional penalty of being ineligible to receive a visa

![]()

13DHS detention is mandatory for most individuals removable on crime-related grounds, aggravated felons, individuals removable on terrorism grounds, arriving noncitizens subject to expedited removal, and individuals awaiting the execution of final removal orders.

DHS Apprehensions by Component Agencies and According to DHS Yearbook

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Border Patrol | 718,291 | 554,996 | 462,453 |

| Office of Field Operations (OFO) | 240,733 | 239,658 | 243,648 |

| Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) | 360,365 | 315,223 | 324,841 |

| Agency Totals (Border Patrol, OFO, and ICE) | 1,319,389 | 1,109,877 | 1,030,942 |

| DHS Yearbook | 791,568 | 613,003 | 516,992 |

| Agency Totals Minus Yearbook Figure | 527,821 | 496,874 | 513,950 |

SOURCES: Data from Border Patrol, Office of Field Operations, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement public-use files provided by ICE and DHS Office of Immigration Statistics and DHS Yearbook (U.S. Department of Homeland Security [2011d]).

![]()

aThis discussion is informed by conversations with experts at the DHS Office of Immigration Statistics concerning the reasons for the large observed differences between the numbers published in the Yearbook and the numbers provided to the committee by DHS for this study.

bln addition, all three of the key DHS figures considered here—apprehensions, voluntary returns, and removals—are based on event counts, not case histories, and so the data do not account for individuals who reenter the United States and are counted multiple times.

to return to the United States for 5 years, and they are ineligible for 20 years after a second or subsequent removal (INA §212(a)(9)(A)). Illegal reentry after such an order is a felony (INA §276).

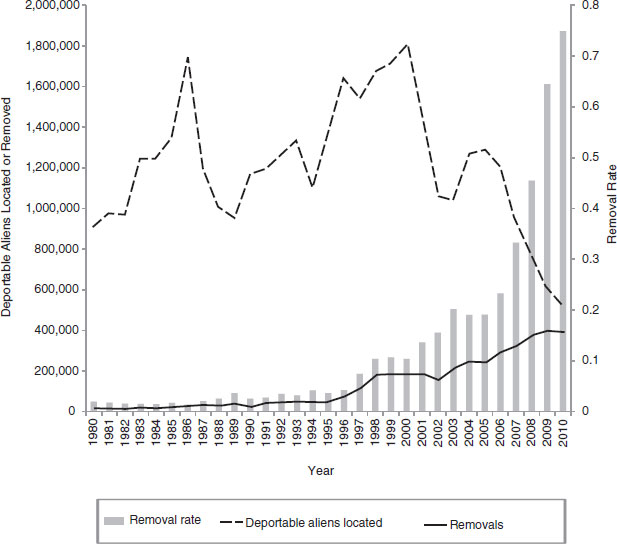

The number of formal removals has increased over the past two decades from an average of 22,000 per year during the 1980s, to 79,000 per year during the 1990s, to 238,000 per year during the 2000s, and it continues to trend sharply upward: see Figure 4-3. As Figure 4-3 shows, removals increased sharply in 1997, the first year under the streamlined enforcement provisions passed in 1996, and they increased again in 2003, the first year after enhanced enforcement efforts implemented in the wake of 9/11. Removals averaged 380,000 per year in fiscal 2008 through fiscal

FIGURE 4-3 Deportable aliens located and removed, 1980-2010. NOTE: Annual data, not seasonally adjusted.

SOURCE: Data from U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2011d).

2010. Removals in fiscal 2011 reached an all-time high of 396,906 (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2011). ICE officials have indicated that the agency’s current resources limit formal removals to about 400,000 per year (Morton, 2011a).

The bars in Figure 4-3 depict the number of removals in a given year as a proportion of the number of deportable aliens located, as reported in the DHS Yearbook (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2011d). Although this proportion does not precisely measure the percentage of undocumented immigrants apprehended in a given year who are removed, it may be roughly interpreted as DHS’s “removal rate.”14 Defined this way,

![]()

14The “removal rate” as defined here is not exactly the percentage of aliens apprehended that is removed, because it is based on the number of deportable aliens located reported

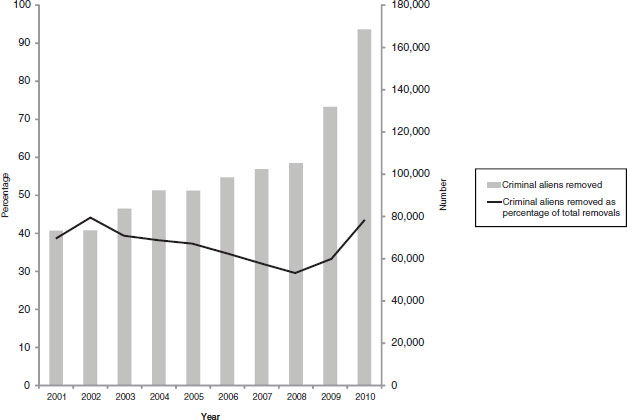

FIGURE 4-4 Criminal aliens removed, 2001-2010.

SOURCE: Data from U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2011d).

the removal rate never exceeded 10 percent prior to 1997: it then rose dramatically—to 20 percent in 2006 and to 75 percent by 2010.

The number of criminal removals has risen significantly over the past decade, more than doubling, from 73,298 in 2001 to 168,532 in 2010. Criminal alien removals as a share of total removals, however, declined from 45 percent in 2001 to 30 percent in 2008, and then rose back to 44 percent in 2010: see Figure 4-4. ICE reports a 55 percent rate for its 2011 removals (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2011).

Given the stakes, undocumented immigrants in formal removal proceedings are entitled to certain due process protections, which constitute the “standard removal process” (see Figure 4-1); certain categories of aliens are subject to an accelerated removal process (i.e., with more limited due process protections). The rest of this section describes various aspects of standard and accelerated removal (see also Legomsky and Rodriguez, 2009).

![]()

in the Yearbook of Immigration Statistics—which is itself a subset of all potentially removable aliens apprehended (see Box 4-1). In addition, the “removal rate” does not account for the time lag between an alien’s apprehension and his or her removal, which causes some aliens to be removed in different fiscal years from the one in which they are apprehended.

Standard Removal Process

Under the standard removal process, DHS initiates a removal hearing before an immigration judge by serving a person with a Notice to Appear (NTA) and filing the NTA with the immigration court. At the subsequent hearings, attorneys from DHS represent the U.S. government; the immigrants, at their own expense, may also be represented by counsel. The work of more than 235 immigration judges in 59 immigration courts around the country is coordinated by the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) in DOJ.

If the immigrant is found to be deportable by the immigration judge, he or she may apply for one or more forms of affirmative relief, which include voluntary return, cancellation of removal, adjustment of status, and asylum. The immigration judge’s written decision must contain findings as to deportability, and it must also include a formal order that either directs removal to a specified country, terminates proceedings, or grants voluntary return. If the immigration judge finds that the immigrant is removable and does not grant any affirmative relief, the immigrant may appeal to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), which may conduct a de novo review of legal and discretionary determinations but is prohibited from reversing an immigration judge’s findings of fact unless they are “clearly erroneous.” If the BIA affirms the removal order, the immigrant may appeal the order to the appropriate federal circuit court of appeals. At each stage of this process, an immigrant who is not subject to mandatory detention may be ordered by an immigration judge to be detained by DHS while the removal proceeding is pending.15

Accelerated Removal

Congress has sought to reduce the costs and delays of formal removal by limiting due process protections in certain categories of cases in which removability is relatively clear. It has established three types of accelerated removal procedures: expedited removal, administrative removal, and reinstatement of an earlier removal order (see Figure 4-1). Aliens falling into one of these three categories face mandatory detention (at DHS expense) throughout the removal process and enjoy very limited

![]()

15ICE estimates that about 85 percent of removable aliens released on bond (i.e., not held in detention) who have been issued a final order of removal abscond, meaning that they fail to appear at a subsequent removal hearing or to comply with the order of removal (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2006). The number of absconders has been estimated at 623,292 in August 2006 and 560,000 at the end of fiscal 2008 (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2007).

opportunities to petition for relief.16 Even if they are placed in standard removal proceedings, immigration judges have limited discretion to offer relief from removal to immigrants in these categories (particularly aggravated felons).

Expedited Removal. Newly arriving aliens without valid travel documents may be subject to expedited removal under INA §235(b)(1). This DHS procedure is conducted primarily at the border.17 Expedited removals are an important enforcement tool. (In the Tucson sector, more than 50 percent of removal proceedings initiated by the Border Patrol are expedited removals.) Without them, immigration court dockets would be even more backlogged than they are now. Expedited removal proceedings sometimes have formal trappings that are intended to emphasize the gravity and consequences of the removal.18

Administrative Removal. Aliens who are not legal permanent residents and who have been convicted of a criminal offense identified by the INA as an aggravated felony (§101(a)(43))19 are subject to administrative

![]()

16First, aliens may rebut the grounds for removal by making a factual claim that they do not meet the specific eligibility requirements described above (e.g., that they have been in the country longer than 14 days, that they are a legal permanent resident, that they have not been convicted of an aggravated felony, or that they are not subject to a previous removal order). Such claims are heard by the appropriate DHS official, who may either affirm the removal order, transfer the alien into the standard formal removal process before an immigration judge, or release the person if the official finds no grounds for removal. Second, aliens may claim political asylum if they fear persecution or torture in the country of origin. In such cases, a DHS asylum officer interviews the immigrant to determine whether the person has a “credible fear” of persecution or torture, in which case the immigrant is placed in a standard formal removal proceeding where he or she can seek political asylum before an immigration judge. A finding by a DHS asylum officer that “credible fear” does not exist is final.

17Under DHS regulations, an immigration agent at a port of entry may issue an expedited removal order to an alien lacking valid travel documents who is apprehended there; to an alien from a country other than Mexico who is encountered within 100 air miles of the U.S. international land border within 14 days of an illegal entry (i.e., one who cannot prove that he or she has been continuously present in the United States for longer than 14 days); and to an alien from a country other than Mexico who arrived illegally by sea and has been in the United States for less than 2 years (67 FR 68924, 69 FR 48877).

18In Tucson, for example, the Border Patrol has created a structured expedited removal advisement (SERA) process. Apprehended immigrants are shown a video in which a CBP agent wearing a suit and tie and sitting on a judge’s stand explains what is happening to them. The immigrants then stand up, and a field operations agent reading from a script asks them individually if they have understood exactly what they were told. Each immigrant then puts his or her fingerprint on the appropriate document.

19“Aggravated felonies” are a class of criminal violations, created by the INA (§101(a)(43)) in 1988 and frequently expanded since then, which includes a long and sometimes ambiguous list of criminal offenses, some of which may not constitute a felony under state or federal

removal under INA §238(b) after they have served their sentences. These proceedings are normally conducted by DHS on paper, without an interview or evidentiary hearing.

Reinstatement of Earlier Order of Removal. Aliens who reenter the United States after having been removed or having departed voluntarily under an order of removal are subject to immediate removal under INA §241(a)(5); the prior removal order is reinstated by DHS from its original date and is not subject to reopening or review.

Immigration-Related Criminal Charges

Certain immigration-related offenses carry criminal penalties under federal law (see Figure 4-1). Immigrants apprehended at or between ports of entry may be charged with illegal entry, a misdemeanor punishable with up to 6 months in federal prison (8 USC §1325). For second or subsequent violations, including reentry after a formal removal order, the immigrants may be charged with illegal reentry, a felony punishable by up to 2 years in federal prison (8 USC §1326); unauthorized immigrants with prior criminal records are more likely to be charged with felonies (Administrative Office of the United States Courts, 2008). Unauthorized immigrants also may be subject to felony charges associated with smuggling, visa fraud, and other forms of document and identity fraud.

The U.S. Marshals Service (USMS) in DOJ is responsible for the mandatory detention of immigrants subject to criminal immigration charges; USMS does not have facilities of its own, so it leases beds in existing facilities. Unauthorized immigrants subject to criminal prosecution are automatically placed in formal removal proceedings20 at the conclusion of their criminal sentences,21 and they are then transferred from USMS detention to DHS detention and remain in DHS detention until their deportation.

The increased penalties associated with immigration-related crimi-

![]()

law. Aliens who have been convicted of an aggravated felony are subject to administrative removal regardless of when the offense was committed and the sentence that was imposed. They also are subject to a longer bar on future admission to the United States (20 years), and in most cases, they are permanently ineligible for U.S. citizenship.

20Depending on their individual circumstances and potential eligibility for discretionary relief, some immigrants may end up in a standard removal proceeding before an immigration judge. The committee was told in El Paso that the completion of much of the case processing work during the criminal prosecution phase can create cost savings for immigration courts.

21Generally, convicted criminal aliens must complete their criminal sentences prior to being deported (INA §241(a)(4)(A)).

nal charges also bring additional due process protections: unauthorized immigrants who are facing criminal charges generally have the same legal protections in the criminal court system as U.S. citizens in other criminal proceedings, although in most Southwest border districts immigrants who are facing immigration-related criminal charges face accelerated criminal processing through Operation Streamline (see below). Misdemeanor cases may be heard and disposed of by federal magistrate judges. Felony cases, in which defendants are entitled to appointed counsel, must be tried by federal district court judges, though they may be assisted by magistrate judges, who conduct various pretrial proceedings. Immigrants who are convicted of federal criminal offenses can appeal their convictions to a circuit court of appeals and then, possibly, to the U.S. Supreme Court.

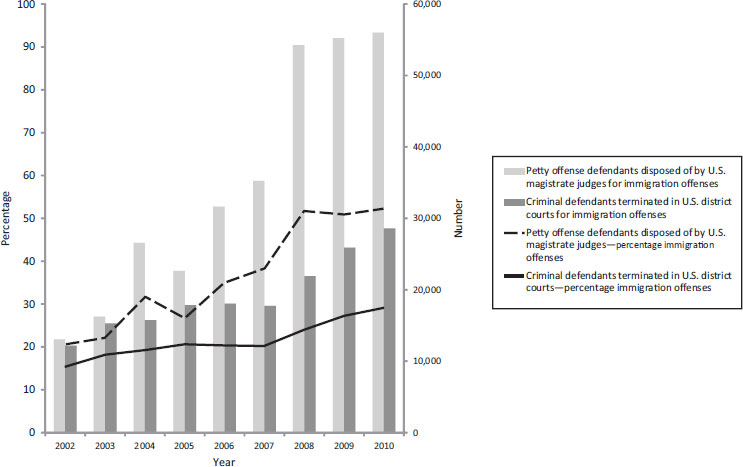

Because of the costs of detention and lawyers, limited prison space, and the emphasis on returning immigrants to their home countries, a lower priority has traditionally been assigned to the prosecution of immigration-related crimes (except in cases involving smuggling or drug operations or other unusual factors). Recently, however, the priority of such cases has been raised: see Figure 4-5. In 2010, approximately 85,000 immigration-related criminal cases were processed in federal magistrate or district courts, an increase from about 25,000 in 2002. Immigration-related cases represented 52 percent of the magistrate court caseload and 29 percent of the district court caseload in 2010, increasing from 21 percent and 15 percent, respectively, in 2002.

These changes, in large part, coincide with the launch of Operation Streamline by the U.S. Attorney’s Office (USAO) in DOJ, federal district court judges, and Border Patrol supervisors in the Del Rio Border Patrol sector of the western District of Texas in December 2005. Under this program, which has since expanded to eight Border Patrol sectors in four federal court districts, USAO files criminal charges against as many immigrants as possible who cross the Southwest border illegally. Arrangements are made in these sectors to permit groups of defendants to have their cases heard at the same time, and federal prosecutors routinely seek plea bargains under which unauthorized immigrants who are subject to felony reentry charges are permitted to plead guilty to misdemeanor charges before magistrate judges (cases which are colloquially known as “flip flops”). In order to increase the likelihood of guilty pleas in illegal reentry cases, DOJ can also authorize federal prosecutors to offer “fast track” sentences that are significantly below the federal guidelines (see Chacon, 2009).

Illegal entry misdemeanors usually carry a sentence of “time served,” which means that the length of the sentence will be determined by how long it takes to process the case. Sentences for flip-flops usually result in 1-6 months’ incarceration under the authority of USMS; longer sentences

FIGURE 4-5 Immigration-related misdemeanors and felonies, 2002-2010.

NOTE: Bars show the total number of immigration cases handled by magistrate judges and district courts, and lines show immigration cases as a percentage of the total cases handled by magistrate judges and district courts.

SOURCE: Data from Administrative Office of the United States Courts (2010).

for felony convictions are handled by the Bureau of the Prisons (BOP) in DOJ.22

IMMIGRATION-RELATED CRIMINAL CHARGES—REGIONAL VARIATIONS IN ENFORCEMENT

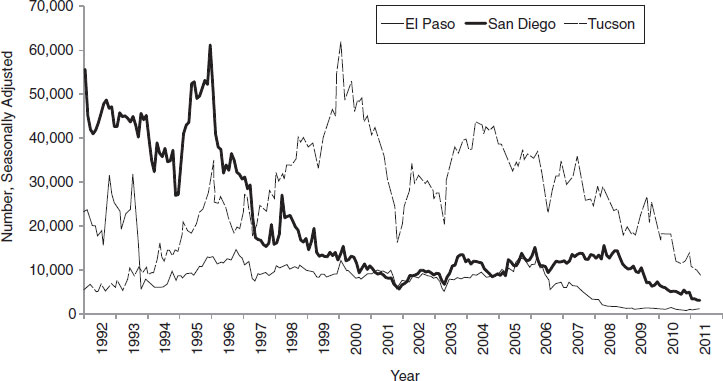

The U.S. immigration enforcement system in the United States is characterized by substantial geographic and regional variation. Modes of border crossing and volumes of apprehension vary significantly by location, as does infrastructure capacity: see Figure 4-6. Long-term trends in apprehensions are down significantly in the El Paso, San Diego, and Tucson sectors. Over the past 10 years, however, Tucson has seen a far higher volume of apprehensions than the other sectors. The operation of the immigration enforcement system and the level of local participation

![]()

22As a result of BOP backlogs, however, transfers out of USMS custody can often be delayed many months, and prisoners can end up serving their sentences in county jails.

FIGURE 4-6 Apprehensions in the El Paso, San Diego, and Tucson sectors.

SOURCE: Unpublished data from Border Patrol with seasonal adjustment by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

in enforcement programs can also differ dramatically, depending on local conditions, resources, and context. Although such regional variations are to be expected in the United States’ decentralized, federal system of government, they can complicate national policy efforts to assess immigration enforcement budget needs.

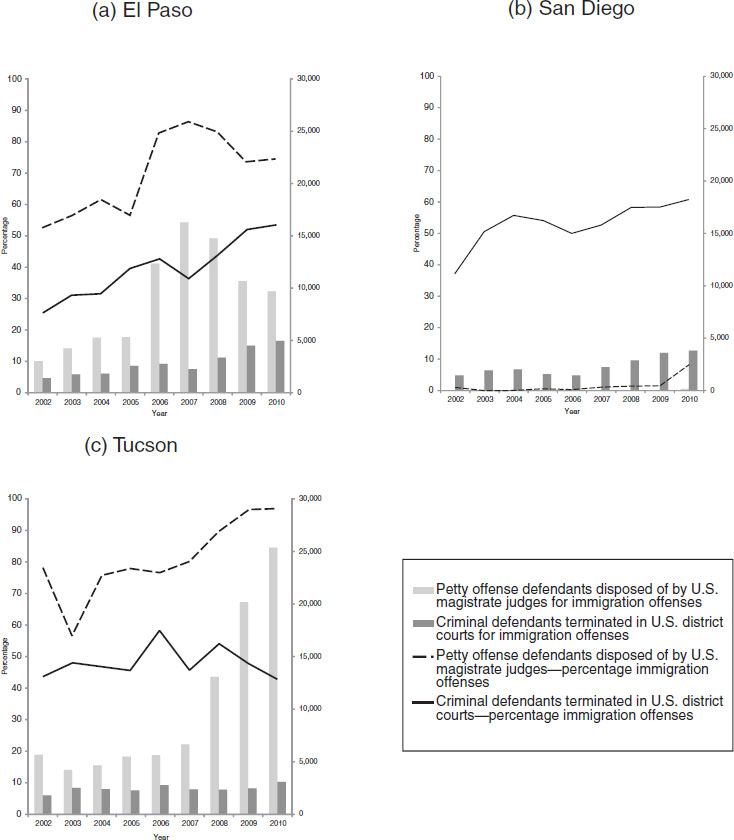

The “criminal pipeline” is a good example of the flexibility of the immigration enforcement system and the regional variation that characterizes it. The implementation of Operation Streamline varies considerably across federal court districts—and it has not been implemented at all in the federal court district that includes San Diego. Figures 4-7a, 4-7b, and 4-7c show the very different levels and trends in immigration misdemeanors and felonies in the El Paso, San Diego, and Tucson sectors.23 In El Paso, the number of immigration misdemeanor cases (indicated by “petty offense defendants disposed of by U.S. magistrate judges”) rose sharply between 2005 and 2007, from about 5,300 to about 16,300, but then fell to approximately 9,700 by 2010. In Tucson, in contrast, the number of immigration misdemeanors has risen steadily between 2005 and 2010, from around 5,500 to around 25,400. In San Diego, meanwhile, the number of immigration misdemeanors has remained consistently negligible.

![]()

23The El Paso, San Diego, and Tucson CBP sectors roughly correspond with the Western Texas, Southern California, and Arizona federal judicial districts, respectively.

FIGURE 4-7 (a) Immigration-related misdemeanors and felonies, El Paso sector, 2002-2010; (b) immigration-related misdemeanors and felonies, San Diego sector, 2002-2010; (c) Immigration-related misdemeanors and felonies, Tucson sector, 2002-2010.

NOTE: Bars show the total number of immigration cases handled by magistrate judges and district courts, and lines show immigration cases as a percentage of the total cases handled by magistrate judges and district courts. SOURCE: Data from Administrative Office of the United States Courts (2010).

However, the three sectors also share certain characteristics. In both El Paso and San Diego, for example, the number of immigration felony cases (indicated in Figure 4-7 by “Criminal defendants terminated in U.S. district courts for immigration offenses”) has increased significantly between 2005 and 2010—from about 2,500 to about 5,000 in El Paso and from 1,600 to 3,800 in San Diego. The sectors are also all characterized by elements of bureaucratic discretion, institutional constraints and bottlenecks, organizational adaptation, and policy communication and coordination. The committee discovered many of these differences and similarities during its site visits to the El Paso, San Diego, and Tucson sectors, as discussed below.

Tucson

In general, Border Patrol agents have considerable discretion over how Operation Streamline is implemented, and their criteria for enforcement may change frequently. For example, enforcement may be geographically targeted, so that all apprehended aliens along a particular segment of the border are sent into the program. Alternatively, the agents may pick out the “worst” offenders (in terms of previous illegal entries, for example). Juveniles, parents traveling with minor children, persons with certain health conditions, and others who require prompt return to their country of origin are usually not subjected to criminal prosecution under Operation Streamline (see Lydgate, 2010).

In Tucson, Operation Streamline tends to be regarded as a Border Patrol initiative, and program prosecutions are generally handled by CBP attorneys who have been deputized by DOJ as Special Assistant U.S. Attorneys, known as “SAUSAs.” The assignment of SAUSAs goes a long way towards reducing the budgetary burden of Operation Streamline for USAO.

The dynamics of felony prosecutions, however, are a bit more complex. Although only USAO can prosecute immigration felonies along the Southwest border, a significant number of those cases are initiated by DHS agents who put together the charging documents and do much of the preliminary paperwork. Although USAO has the authority to decline those cases, the committee was told that political pressures and expectations can make it difficult for USAO to do so without compelling justification. To the extent that many of these immigration cases are less complex and resource intensive than other felony prosecutions, they also might serve as a relatively cost-efficient way of boosting USAO’s prosecution numbers. In addition, one of the most important reasons that USAO in Tucson has been able to prosecute as many felonies as it has is that it was given the resources to enhance its prosecution capacity by hiring additional attor-

neys. Still, staffing levels for legal assistants are regarded as inadequate, even though the supporting role that they play is critical; it was suggested to the committee that allocating additional resources for legal assistants might be politically less “sexy” than hiring more attorneys.

USMS, which does not have discretion over the volume or composition of its workload, is one of the DOJ components that has been especially pressured by the surge in prosecutions. Detention is costly from a budget perspective, and detention facilities are almost always at or near capacity; the committee was also informed that the health care costs of detainees are of significant concern. An equally great (if not greater) challenge for USMS has to do with the personnel required to transport prisoners to and from the federal courthouse. Not only can detention facilities be located several hours away, but the physical infrastructure of the courthouse can also make it challenging for USMS to process detainees.24 For example, detention cells (which are usually at capacity) are located far away from the courtrooms, and there is only a single small elevator that can be used to move the prisoners. Felony prosecutions, which can require multiple trips for prisoners between the detention facility and the courthouse, are more burdensome for USMS than misdemeanor prosecutions under Operation Streamline, which entail fewer procedural steps.

Even though USMS is under considerable stress and strain, the situation does not yet seem to have become unmanageable. The number of Operation Streamline misdemeanor prosecutions in Tucson has been capped at 70 a day, a number that was the product of negotiations between the late Chief Judge Roll and local officials from USAO and DHS. The constraints and bottlenecks faced by the various actors in the immigration enforcement system were taken into account in negotiating that number. Although some would like to increase the number of program prosecutions to 100 a day, many others believe that moving from 70 to 100 cases would destabilize the system. Short of that, USMS, working in concert with the judicial system, appears to have routinized its misdemeanor caseload—the operations at the Tucson courthouse were described to the committee as a “well-oiled machine.” Felony prosecutions, however, are significantly more cumbersome and do not appear to be the object of systemwide negotiation: it was even suggested that the Border Patrol may be responding to the cap on Operation Streamline misdemeanor prosecutions by bringing more immigration cases to USAO as felonies. Continued increases in the number of felony prosecutions may prove correspondingly burdensome for USMS.

![]()

24The committee was also told that the situation in El Paso was similar.

El Paso

In El Paso, Operation Streamline is referred to as being part of a “zero tolerance policy,” with apprehended immigrants being prosecuted at very high rates. According to local officials, about two-thirds of apprehended immigrants were prosecuted in fiscal 2010. USMS in El Paso faces many of the same challenges as USMS in Tucson, and, as in Tucson, cooperative relationships among judges and between attorneys play an important role in helping the system to operate smoothly.

In contrast to Tucson, Border Patrol counsel in El Paso do not assist USAO in handling Operation Streamline misdemeanor prosecutions, even though USAO accepts essentially all of the cases presented by the Border Patrol. Moreover, court proceedings for these cases tend to be completed more quickly than in Tucson (resulting in shorter “time served” for defendants), and USAO operates without the benefit of “fast track” procedures for felony cases. It was suggested that the relatively low level of apprehensions in the El Paso sector (see Figure 4-6) help account for many of these differences.25

And perhaps even more so than in Tucson, the resources and prosecution capacity of USAO in El Paso have managed to keep pace with the volume of cases that it has committed to pursue. Its capacity is such, in fact, that at one point it allegedly sought to charge all first-time illegal reentry cases as felonies, but backtracked from doing so when the public defender’s office responded by counseling defendants to ask for trial, which would have overloaded the system. Now, only repeat offenders with criminal backgrounds are charged with felonies, the overwhelming majority of whom plead guilty.

San Diego

In contrast to El Paso and Tucson, Operation Streamline has not been implemented in San Diego. The resource constraint that is cited most often is the number of beds available to hold undocumented immigrants for criminal prosecution. Because of high real estate prices, the cost of incarceration is said to be significantly higher in San Diego than in other districts. It was suggested to the committee that the number of available beds would have to be doubled in order to accommodate all of the cases that could be prosecuted under the current set of criteria used by USAO. As a result of this constraint, the number of prosecutions is dictated by

![]()

25Given the simple nature of routine immigration cases, USAO in El Paso has also adopted a “horizontal” organizational structure rather than the “vertical specialization” structure that would be typical in offices that did not have such high-immigration workloads.

the beds available for detention rather than by changes in patterns of immigration.

There are differing views as to why the San Diego sector has not participated in Operation Streamline. Some people told the committee that federal authorities, aware that resource constraints would prevent the program from being fully implemented, have chosen not to impose an unworkable program. Other people told the committee that the fact that San Diego has not officially adopted the program has little practical importance, because the basic Operation Streamline principle of privileging criminal prosecution has long been the norm in San Diego, a principle is now reinforced by the “consequence delivery system” being implemented in the sector by DHS. USAO prosecutes cases up to the number of available beds in federal detention facilities, and shuffling prisoners among those facilities is one of USMS’s main challenges. As in Tucson and El Paso, USAO also accommodates the priorities of DHS. For example, in recognition of the importance that CBP has placed on document fraud (in particular, the fraudulent use of U.S. passports), USAO will take those cases even though the crimes involved are less severe than those that are typically prosecuted in San Diego.26

DISCRETION, CONSTRAINTS, ADAPTATION, AND COORDINATION

As indicated in the discussion above, bureaucratic discretion, institutional constraints and bottlenecks, organizational adaptation, and policy communication and coordination are important features of Operation Streamline and immigration-related criminal prosecutions. However, these features also loom large in other parts of the immigration enforcement system, potentially complicating efforts to effectively estimate budget needs for immigration enforcement.

Discretion

Given the decentralized federal structure in which immigration enforcement operates and the nature of the tasks performed, there are many points of discretionary decision making within the enforcement system. As a result, the system can appear to be less coherent and consistent in implementation than it is in design.

In the Tucson sector, for example, ICE appears to be focused on appre-

![]()

26In order to prosecute beyond the capacity of USAO, CBP also works with the California Department of Motor Vehicles to identify types of document fraud that can be prosecuted under state law.

hending as many immigrants as possible, regardless of their “priority” level. It was suggested to the committee that ICE was subject to political pressure to “keep the numbers up” despite declining levels of immigration, causing it to “dig deeper” into prison populations to look for removable noncitizens. However, according to a policy that has been known variously as “prosecutorial discretion,” “nonpriority status,” and “deferred action,” ICE is not actually obligated to put all undocumented immigrants who are suspected of being deportable into removal proceedings (Legomsky and Rodriguez, 2009). In 2011, the assistant secretary of DHS for ICE, issued three memoranda that sought to clarify the role of ICE agents, investigators, and attorneys in exercising prosecutorial discretion on a case-by-case basis with regard to the apprehension, detention, and removal of aliens (Morton, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c). The guidelines in these memoranda encourage deportation efforts to remain focused on high-priority cases and to take account of various mitigating factors. However, the memoranda may not actually materially diminish or constrain the discretion of ICE agents at the local level.

Similarly, Border Patrol and CPB agents have considerable discretion in granting voluntary return (with their decisions reviewed by second-line supervisors) and, more generally, in determining how apprehended immigrants will be processed. The nature of this discretionary decision making is nicely illustrated by a laminated card that is handed out to Border Patrol agents in the Tucson sector. One side of the card lays out the various steps of the “Evaluation Process” for apprehended immigrants, which include checking the appropriate records, reviewing the person’s criminal and immigration history, reviewing the “nexus” of the person,27 classifying the person,28 and reviewing “consequence delivery.”29 The other side of the card is a “Consequence Delivery System Guide,” which consists of a chart that attempts to rank a variety of enforcement options according to the classification of the apprehended alien.30 Like the ICE memoranda discussed above, the guide appears to be advisory rather than obligatory.

![]()

27Nexus options include “Criminal Organization,” “Target/Focus Area,” and “Targeted Demographic.”

28Entrant classification options include “First Apprehension,” “Family Unit,” “Second/Third Apprehension,” “Persistent Alien,” “Suspected Guide/Mule,” “Targeted Guides,” and “Criminal Alien.”

29Reviewing consequence delivery includes evaluating “Previous Actions,” “Expected Outcomes,” and “Possible Path Forward.”

30The guide also notes that “[t]he combination of any of the above consequences is encouraged, especially when the best/most effective consequence cannot be applied.… This chart is Not meant to be inclusive of every illegal alien arrested or consequence available, as there will be special cases in each category.”

Discretionary decision making by DHS agents takes place in, and can be influenced by, a framework of incentives and performance measures. For example, although voluntary returns are systematically recorded by DHS and leave a “paper trail,” they are still less administratively demanding than other enforcement pipeline options. The committee was told in Tucson that, all else being equal, Border Patrol agents may find voluntary returns to be relatively more appealing than other options.

Nevertheless, DHS has made a conscious and concerted effort across sectors to reduce the relative frequency of voluntary returns. In Tucson, the committee was told that CBP has issued a directive to grant fewer voluntary returns; in San Diego, that one metric of success for CBP is the ratio of expedited removals to voluntary returns, with a strong preference for the former; and in El Paso, that officers need to justify their use of voluntary returns. The committee was also told in El Paso that ICE counsel are rewarded according to the number of formal removals that they affect, and the dangerousness of those removed. It may be operationally easier to move away from voluntary returns in a context of declining apprehensions, which may be one reason why voluntary returns are still more common in the Tucson sector than in El Paso (where voluntary returns are limited to “humanitarian cases,” such as family reunifications involving minors).

Immigration judges also have substantial authority and discretion over how removal hearings are conducted and the outcomes of those hearings. In El Paso, the committee was told that the performance of immigration judges is measured by professionalism (i.e., the number of complaints), timely adjudication, and not being overturned on appeal. Nevertheless, in Tucson the decisions of immigration judges on such issues as cancellation of removal were criticized for being highly variable, and the committee also heard criticisms about the bonding process being highly discretionary and inconsistent.31 It was also suggested to the committee in El Paso that immigration judges with prosecutorial backgrounds are more likely to side with the government.

In August 2011, DHS announced that it would form an interagency working group with DOJ to review the cases of about 300,000 people currently in deportation proceedings. Under this policy, deportations would be suspended on a case-by-case basis in “low-priority” cases, such as those involving immigrants who do not have criminal backgrounds and were brought to the United States as young children. The working group will initiate a similar case-by-case review for new cases placed in removal proceedings, and it will also issue guidance on exercising prosecutorial

![]()

31For a discussion and empirical analysis of adjudicatory inconsistencies and variability in the immigration enforcement system, see Ramji-Nogales et al. (2007).

discretion for compelling cases (Napolitano, 2011; Pear, 2011; Preston, 2011). Although this policy initiative is based on similar principles of prosecutorial discretion outlined in the ICE memoranda discussed above, it is broader in jurisdictional scope, going beyond ICE. It also has a retrospective dimension that is more than just exhortatory and may systematically affect the ways in which front-line agents exercise discretion. Much will depend on how the policy is implemented and how it informs and influences the choices made by agents and officials across the various sectors.

Institutional Constraints and Bottlenecks

Although DOJ is not responsible for the detention costs of aliens who are brought before immigration judges, it is nevertheless affected by the availability of DHS detention bed space because it can affect the volume of cases heard by immigration judges. In El Paso, for example, DHS detention capacity has been greatly expanded, but there has not been a corresponding increase in resources for immigration courts. Because of the availability of detention space in El Paso, immigration judges are hearing the cases of detainees who have been brought in from other parts of the country, including from California and New York. Referrals from the Secure Communities Program and local law enforcement have also been growing rapidly, which has resulted in higher workloads and growing backlogs for immigration judges.

In El Paso, the committee was told that an initial appearance before an immigration judge can take more than 30 days, cases are taking longer to resolve, and that there is a growing discrepancy between the time to resolution of cases in the detained and nondetained dockets: detained offenders are seeing their cases resolved in 4-8 months while nondetained cases are taking 2-4 years. In El Paso and Tucson, asylum cases were noted to be especially difficult and time consuming.32

Immigration adjudications may be affected by case processing constraints in other agencies. In San Diego, for example, the committee was told that immigration judges cannot act until DHS has taken fingerprints and done background checks, which can take weeks or months. Similarly, the committee was told in Tucson that the division of the bonding process among CBP, ICE, and the immigration courts may produce gaps in needed information and that, more generally, the information systems and technology that DHS has in place in its detention facilities may not always be adequate for processing cases expeditiously.

![]()

32In San Diego, the committee was told that the most rapidly growing category of cases consists of migrants who crossed the border without documents at a port of entry and then asked for asylum.

With regard to interior enforcement (i.e., enforcement that does not take place at the border), the decision to seek 287(g) agreements with ICE may be influenced by not only local political pressures (Capps et al., 2011), but also by logistical considerations. El Paso and San Diego, for example, have chosen not to seek 287(g) agreements because the federal government does not reimburse for costs, and local officials instead find it more cost-effective to allow ICE agents to have access to jails as they do under the Secure Communities Program (El Paso and San Diego Site Visits). In the absence of 287(g) agreements, local law enforcement can still exercise their discretion to call Border Patrol or ICE agents if a person’s undocumented status comes to light during initial questioning. However, the downside of not participating in programs like 287(g) is that in rural areas away from the border, federal agents may not be available to pick up apprehended immigrants, who are then often released.

Institutional Adaptation and Innovation

There is considerable potential for institutional adaptation and innovation in the face of resource constraints and other bottlenecks. It should also be noted, however, that these organizational responses can have (sometimes adverse) administrative and legal implications for immigrants being processed by the enforcement system.

“Quick courts” in the Tucson sector are a good example of institutional adaptation by immigration courts. There are about 30 quick court cases a day, and they tend to be relatively uncomplicated. Immigration judges receive charging documents for newly apprehended immigrants in the morning and hold hearings in the afternoon; the immigrants are advised of their rights en masse and then come to immigration court two at a time. Getting the paperwork ready for these cases is a very labor- intensive and time-sensitive process, and it requires a very close working relationship with the Border Patrol (which perceives quick court as a supplement to Operation Streamline). Judges can determine the time allotted for trials and have the discretion to set the limit, process, and criteria for quick courts.

Aside from quick courts, some judges take the initiative to provide detainees with a printed list of the things that they need to bring with them the next time they come to court. Failure on the part of the detainees to provide this information can delay the hearing process and extend the time spent in detention; immigration attorneys claim to see a difference in the court calendars of immigration judges who do and do not use these forms. The committee was also told about a more systematic adaptation, known as the Institutional Hearing Program, which enables DHS to save

on detention costs by allowing immigration judges to hold hearings in prisons while deportable criminal aliens are still in state custody.

In order to minimize DHS detention costs and unnecessary restrictions on liberty, immigration judges may also order individuals who are removable to participate in an electronic monitoring program or some other alternative-to-detention program while awaiting a final adjudication. Under such programs, ICE uses technology (electronic monitoring) and case managers to track aliens in removal proceedings. As many as 94 percent of the people in alternative-to-detention programs appear at their removal proceedings, and the cost of monitoring aliens in these programs is about one-fourth the cost of traditional detention (U.S. House of Representatives, 2006).

Communication and Coordination

The decentralized and discretionary nature of the immigration enforcement system, with adaptive responses that are often piecemeal and ad hoc, can make it difficult for system actors to communicate and (even more importantly), to coordinate their work. The fact that DHS’s own information systems may often be inadequate (as mentioned above) can make coordination with DOJ that much more difficult. These problems are only exacerbated by different lines of bureaucratic accountability and the divergent incentives faced by various actors. The committee was told in Tucson and San Diego that even within DHS, there can be a lack of coordination and cooperation between ICE and Border Patrol, and the different data-gathering and reporting systems in DHS may also be inadequately harmonized (see Box 4-1). These intraagency incongruities can make interagency collaboration that much more daunting.

Even though there are few formal incentives for coordination and cooperation, informal cooperation among multiple agencies has been essential to the operation of programs such as Operation Streamline. However, the existence of cooperation and trust often stems from long-term working relationships on the ground and may be predicated on the orientation of individual leaders; these ties can all too easily be disrupted by (among other things) the rapid turnover of personnel, which is not uncommon in the immigration enforcement system. Existing levels of cooperation and coordination may be sufficient to keep the system from “crashing,” but more may be required to achieve higher standards of performance and better outcomes.

The description of the U.S. immigration enforcement system in this chapter highlights certain system characteristics that are relevant to the problem of estimating the resources required for its effective performance. First, it is a decentralized system in which important decisions are delegated to the regional level and, then, to operating, front-line personnel who in many cases have to exercise discretion in real time and in difficult situations. The ways in which system actors exercise discretion may be influenced—although not necessarily entirely determined—by an array of formal incentives and guidelines and informal administrative and political pressures.

Second, the immigration enforcement system is generally “stovepiped,” both at headquarters and (perhaps to a lesser extent) at the local, district, and sector levels. That is, separate agencies tend to make separate policies, sometimes but not usually in systematic coordination with one another. It is also important to distinguish between informal and ad hoc cooperation between DHS and DOJ personnel at the field level, and coordination between DHS and DOJ as a whole.

Third, many operational priorities and, sometimes, general policies are shaped by practical resource limits and localized bottlenecks, such as limited courthouse space or bed space. To some extent, the decentralized and discretionary nature of the system allows local administrators—to some extent—to adapt to those constraints given current resources rather than simply waiting for more budgeted resources to arrive.

Fourth, the ability to quantify the flows of apprehended immigrants through the enforcement system and, therefore, to understand more fully the basis for those flows is limited by incomplete data on the subsequent handling and disposition of individual cases. Without such case histories, it is very difficult to determine—let alone anticipate—the specific pipeline implications of, for example, increased apprehensions through the Secure Communities Program, technical innovations that make it easier to efficiently identify and locate visa overstayers, or systematic changes in the exercise of prosecutorial discretion by front-line agents. Moreover, there are marked discrepancies between published (and widely used) statistics on apprehensions and the data on apprehensions that were supplied to the committee, and these national-level discrepancies may be even more pronounced at the regional/sector level. All of this suggests that many of the planning and budgeting decisions with regard to immigration enforcement might be based on information that is inadequate and incomplete.

Finally, the system’s policies and operations are continually evolving, both in response to changing external conditions and in response to changing political judgments. External factors, such as changing flows of

undocumented immigrants, can interact with the complex system in ways that are difficult to predict. For example, even though apprehensions have fallen during recent years, the demands on other system components have still generally risen, largely because of efforts to impose greater personal consequences on illegal immigrants and to thereby deter their efforts to enter or reenter. So far, the effects on the enforcement system of this strategic policy shift have been mitigated by the decline in apprehensions. Conversely, a future surge in apprehensions might quickly strain the capacity of many agencies and create pressures to either increase resources rapidly or abandon the policy of enhanced consequences.

As explored in the following chapters, all of these system characteristics have implications for budgeting. Taken together, they pose a great challenge to those who would use simple rules of thumb or standard statistical techniques to forecast activity levels and resource needs even 1 or 2 years in advance. A different approach may help, and that is the focus of the rest of this report.