A primary task of budgeting is to estimate the level of resources that will be needed in the future to support the work of established agencies, programs, and activities. Another important task of budgeting is to identify and assess alternative ways that resources could be used more effectively to accomplish a given set of policy goals. The people who are responsible for budgeting and appropriating funds for immigration enforcement will never have an easy time with either of these tasks.

Budgeting for the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) components of the immigration enforcement system will always be hampered by the system’s complexity, dynamism, and uncertainty. But steps can be taken to help meet those challenges. For example, it might be possible to narrow the range of budgeting surprises—unanticipated service demands that seem to require additional budget resources for one or more DOJ components, or if that is not possible at least to mitigate their effects. And, it may be possible to inform budget choices with better information and analysis of the possible effects of alternative resource uses, so analysts can help policy makers better apply resources to meet the policy goals of immigration enforcement and not merely meet current program needs.

We begin this chapter by recognizing the generic challenges that face analysts and policy makers for any complex, dynamic administrative system. We then draw on the committee’s field observations of the immigration enforcement system and its recent evolution to describe additional obstacles specific to the immigration enforcement system. The complexity of that system makes it unrealistic to look for technical solutions in

the form of sophisticated modeling methods, but budgeting could be improved through improved data collection and new analyses that relate resource levels and uses to results.

Federal departments and agencies develop budgets by first estimating what level and mix of resources they will need to execute authorized or proposed activities, consistent with legal mandates and policy objectives. Resource estimates therefore reflect both cost information and policy choices about program objectives and means. As described in Chapter 5, the budget process requires that agencies develop estimates well in advance—typically 18 to 24 months—of the period for which funding is sought, adding to the challenge. Because the budget process is lengthy and spending demands are characterized by uncertainty, agencies find it challenging to accurately estimate their resource needs when budgets are drafted.

Agencies may take one of two broad approaches to developing budget estimates. The first and most straightforward is a high-level incremental approach.1 Starting from the recent pattern of budget requests and variances (e.g., supplemental requests, reprogramming, and rescissions), budget planners account for overall spending trends and adjust for any new information expected to affect future resource requirements. To caricature: “If in the past you believe evidence suggests the U.S. Marshals Service was underbudgeted by 2 percent, then in the future bump up the budget request for the U.S. Marshals Service by 2 percent, all else equal,” or “If in the past, the U.S. Marshals Service has made do with a flat budget, then in the future provide the U.S. Marshals Service with a flat budget unless and until new information justifies an increase or decrease.”

For policy and program areas in which the processes underlying budget demands are understandable and relatively stable, incremental methods often suffice to produce reasonably accurate estimates of future resource requirements. For many annually appropriated programs, this approach works quite well. For low-income housing subsidies, for example, the funding needed to sustain a given level of service is readily

![]()

1Incremental budgeting is the oldest and simplest approach to developing budget estimates for public programs (see, e.g., Schick, 2007, Chapter 1). The distinction made here between incremental and other technical approaches is highly stylized, and it does not address the institutional and political determinants of budget and appropriations decisions that often modify or supersede technical judgments. Moreover, empirical research on budgeting decision making has thrown doubt on whether incrementalism or any other decision-making model can explain trends in funding for agencies, programs, or budget accounts; for a convenient summary of this research, see Meyers (1994), pp. 1-18.

calculated by applying an inflation factor to rents and utility payments and a growth factor to average incomes of the eligible population. Or, for the air traffic control system statistical regression and other more sophisticated statistical methods can be used to supplement or improve on simple incremental adjustments. For other government programs, estimation challenges are even greater. At the extreme, some needs are nearly impossible to accurately estimate in advance on the basis of trend analysis or actuarial modeling or even with more elaborate multivariate statistical models. A prime example is the problem of budgeting for emergencies, such as natural disasters and other large, unpredictable, high-impact phenomena, such as terrorist attacks or financial crises. For these situations, budget planners often appropriate to reserves or “rainy day” funds to meet some portion of emergency needs and are prepared to seek supplemental funds after an event to meet additional needs.

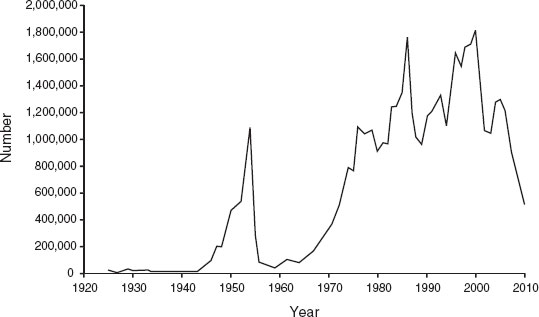

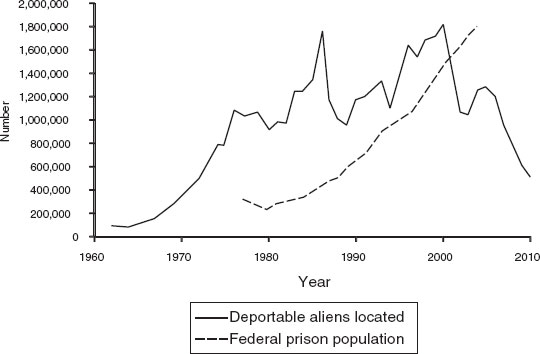

So what method of estimation should DOJ use to develop initial estimates of resource needs for the immigration enforcement budget? A primary driver of service demand for DOJ immigration enforcement is the number of people apprehended as unauthorized immigrants each year. As described in the preceding chapters, the number of people who reach DOJ depends in part on policies of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), e.g., the proportion prosecuted and the proportion offered voluntary return. To illustrate the degree of variability over time, we focus here on the total number of deportable aliens located as reported in the DHS Yearbook (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2011d), though we note that it understates the numbers apprehended (see Chapter 4). As shown in Figure 6-1, DOJ immigration enforcement case volume or services demand from apprehensions has been quite variable over time, not just recently, but over the past 80 years. For comparison, this demand is radically more variable than is, say, the provision of “imprisonment services” provided by federal prisons, as shown in Figure 6-2.

Another broad approach to producing budget estimates considers the likely behavior of various individuals and organizations in the system under likely future conditions to try to forecast actual resources needed (number of staff, processing facilities, detention beds, etc.) on the basis of those anticipated behaviors. Such structural modeling approaches can be applied to estimate dollar requirements for a given level and quality of service. Organizations can budget for either a specified quantity of service provision or a specified level of service quality. The former approach (a

FIGURE 6-1 Deportable aliens located, 1925-2010.

SOURCE: Data from U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2011d).

FIGURE 6-2 Comparison of federal prison population and deportable aliens located, 1962-2010.

SOURCES: Data from U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2011d) and U.S. Department of Justice (2005).

specified quantity of service) is much easier when demand is volatile and uncertain, as is the case for immigration enforcement.2

A budgeting approach that begins by modeling the structure of the services system is much more demanding of information and analysis than incremental approaches, but for complex and dynamic systems like the one encompassing migration flows and immigration enforcement, extrapolation-based methods are unlikely to produce consistent and accurate estimates of resources needed to meet service demands.3 Indeed, although DOJ’s recent budget history includes few major reprogramming or supplemental funding requests, the appearance of stability in the budget process largely reflects DOJ’s capacity to “make do” or adjust its operations to variable service demands within fairly broad limits though with effects on quality (see Chapters 4 and 5). Developing estimates of resource requirements for such a system may depend on understanding how actors in the system (and those outside the system, such as other governments and potential undocumented immigrants) are likely to behave in the future. Is such a modeling approach possible for DOJ’s parts of the immigration enforcement system? To answer this question, the committee examines both challenges posed by the nature of the immigration system and the social environment in which it operates and from the limits of information available to budget planners.

THE PARTICULAR CHALLENGES OF BUDGETING FOR IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT

In addition to the usual challenges of budgeting, DOJ confronts at least five additional challenges to projecting its resource needs for immigration enforcement that are specific, to varying degrees, to the immigration system:

1. the nonlinear nature of relationships within the administrative system responsible for executing immigration enforcement policy;

![]()

2Apprehended unauthorized immigrants can be seen as “customers” generating demand on DOJ’s parts of the enforcement system. Service quality (however defined) is a function of service capacity and demand. When demand is too high for a given service capacity, then service quality suffers. In standard business applications, for example, poor service quality often manifests in long customer waits. Defining service quality for public services, such as immigration enforcement, is typically more complex than for many other services, but it includes assurance of due process, just treatment of those apprehended, and that the personal cost of violating immigration laws is not so low that it undermines the effectiveness of enforcement in reducing or deterring illegal immigration.

3See Appendix B for a review of major efforts to model workload and resource requirements for federal immigration enforcement and similar criminal justice processes.

2. adaptive behavior by both enforcement agents and immigrants;

3. jurisdictional complexity and dispersal of authority;

4. policy shifts and shocks to the migration system that are outside the DOJ budgeting process; and current limitations on data on costs and performance.

As discussed below, the immigration enforcement system presents challenges akin to those of a queuing system, which, in turn, implies nonlinearity, adaptive behavior, and noncorresponding jurisdictions. Not only does DOJ—its staff and the organization, writ large and small— adapt to changes in its operating environment, but also so do those who might interact with DOJ, including representatives of other agencies and potential unauthorized immigrants. As a consequence, only some of the challenges in this category are under DOJ’s control.

Queuing and Nonlinearity

DOJ’s processing of cases (people apprehended as possible unauthorized immigrants) involves taking them through various stages of legal review, during which they may be detained and at the end of which they may be incarcerated or, in most cases, removed from the country. The movement or flow of cases through this administrative system, as described in Chapter 4, is limited by constraints at various points—notably by the number of available detention beds and by the limited capacity of immigration courts and federal courts and their facilities. Cases in excess of capacity at one or more points of resource constraint must either be held before further processing or diverted to other administrative channels—for example, released rather than detained pending review of their status or returned without formal processing or with administrative processing by DHS only—rather than passing through formal proceedings and then ordered removed.4 The cost of delays in processing—including costs of detention and related transportation, food, and health care—make waiting a direct driver of one of DOJ’s largest and least predictable cost elements and therefore an important source of administrative inefficiency.

A fundamental observation of the study of such queuing is that sys-

![]()

4In technical terms, DOJ’s processing of immigration cases is a queuing problem, that is, a problem in which a group of “customers” wait in line to obtain a service, a service provider makes decisions about how it will allocate resources to various “servers,” and the customers’ wait time depends on those decisions. Unauthorized immigrants and their associated cases are “customers”; DOJ is the service provider; DOJ assets (e.g., U.S. marshals, lawyers, immigration judges, and facilities) are “servers.” Managing queues involves striking a balance between the cost of the “system” (the cost of paying for the servers) and the cost of poor service quality—generally and, most obviously, of waiting.

tem performance metrics, such as the average number of cases or customers waiting in the system, are a highly nonlinear function of system utilization. Utilization means, roughly, how busy the providers of service (servers) are or the ratio of customer demand to the number of servers and their service rates. In particular, these curves have an “elbow”: increasing demand always increases waiting times, but initially that increase is fairly slow and almost linear; then, rather suddenly, the system moves from functioning well to becoming dysfunctional, and, absent any other changes, waiting times shoot up: see Box 6-1.

The immigration enforcement system involves not just one queue, of course, but a system or “network” of interrelated queues. If increased case volume at one “node” (i.e., for one particular queue) hits a limit of service capacity and is not met immediately with an increase in capacity, then back-ups at that point in the system can spill over and affect demand at other points in various ways, creating additional nonlinearities.

A recent surge in illegal immigration in the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector shows at least two such spillover effects. First, the increased illegal flows into Arizona reflected a behavioral response by immigrants, as migration flows shifted to Arizona in the wake of new enforcement resources put in place in Texas and California beginning in the 1990s. Second, within the Tucson sector, the rising number of unauthorized immigrants facing formal removal and criminal charges produced nonlinear spillovers at various nodes in the DOJ enforcement process, most notably at choke points in holding cells, court rooms, and transportation capacity. In this queuing network, as in many others, departures from the previous period’s operating conditions rippled through the network, making it impossible to estimate volume or service provision at other nodes in the system on the basis of linear extrapolations of their own recent pasts.

Even in a single location that is providing what from the outside looks like a single service, there can actually be parallel issues when the location’s service rate is determined by the most restricted of several complementary assets. A highly memorable example is the reported problem in one border location with a slow, small courthouse elevator that is the only way that defendants can get to or from the courtroom.5 In such circumstances, hiring more judges or marshals may not increase service capacity. A budget analyst without local knowledge might project no change in average waiting time of defendants in the system if DOJ personnel budgets were expanded in parallel with anticipated increases in workload; but if the elevator is the bottleneck, negating the benefits of

![]()

5An interesting example of this phenomenon comes from how police response to the crack epidemic of the 1980s put services pressures on other law enforcement “downstream” of the arresting agency: see Press (1987, pp. 541-569).

BOX 6-1

An Illustration of Queuing Effects

If the waiting time per customer were linear in utilization, forecasting would be fairly easy. For example, if demand (the number of unauthorized immigrants fed into the DOJ system by DHS) were going to go up by 20 percent with no change in DOJ’s service capacity, then the wait time per person would go up by 20 percent, and the total time waiting would go up by 44 percent (20 percent more customers each waiting 20 percent longer, plus a 4 percent “interaction” effect). If server costs remain the same, customers must bear the cost of the additional resource demands in the form of longer wait times. Alternatively, if server capacity (and associated costs) also were allowed to increase by 20 percent, then the total amount of waiting would increase by 20 percent (20 percent more customers, each waiting the same amount of time), and so would server costs: see table below.

Unfortunately it is not that easy. Depending on the actual operation of the system and its prior state, a 20 percent increase in demand can increase waiting per person by 20 percent, less than 20 percent, or more than 20 percent, with no real upper bound. The simplest example of a nonlinear queuing response function is the so-called M/M/1 queue, for which the average time users spend in the system in steady state equals the reciprocal of the difference between the service rate and the customer arrival rate.* In this case, if utilization was originally 80 percent and demand increased by 20 percent, then waiting time would increase by 400 percent. Linear estimation, and therefore linear budgeting, just does not work in such circumstances.

| Scenario | Number of People | Wait Time per Person | Total Wait Time for People | Server Cost |

| Baseline | 100 | 1 hour | 100 hours | $1,000 |

| 20% increase in people with no increase in capacity | 120 | 1.2 hours | 144 hours | $1,000 |

| 20% increase in people with 20% increase in capacity | 120 | 1 hour | 120 hours | $1,200 |

![]()

* In mathematical terms, W = 1 / (μ – λ), where W is wait time, μ is the service rate, and λ is the rate at which people arrive. Thus, W explodes toward infinity as λ approaches μ.

more staff, then queues of defendants waiting for their day in court could still explode, with follow-on costs from increased detention numbers and spillover effects on other parts of the system. To generalize, there can be ripple effects when infrastructure (capital) investments are not in sync with increases in personnel.6

Adaptive Behavior and Instability

Standard statistical techniques used to model social systems assume that the way the parts of those systems interact with each other and their environment is stable over time. Yet in the case of the immigration system, resource demands change over time because of two forms of adaptive behavior:

1. adaptations by service providers, such as prosecutors or immigration judges, who change the amount of time and resources invested in each “customer” by developing more efficient mechanisms to place immigrants in formal removal and subject them to criminal charges; and

2. adaptation by potential unauthorized immigrants, who respond to new enforcement procedures by adjusting, for example, their efforts to enter and evade apprehension, which mean that resource demands for a given level of illegal immigration change over time, and they are a barrier to statistical estimation or modeling based on past behavior and therefore to prediction for budgeting.

Adaptive Behavior by DOJ Decision Makers and Administrators

DOJ’s resource requirements depend on the number of individuals entering the immigration enforcement system and on how the system

![]()

6Private industry faces structurally similar problems (i.e., networks of queues facing volatile demand and, in some instances, strategic interdependencies both within and across firms). However, it is not as clear that businesses face a similar budgeting problem. For example, a manufacturing operation can be modeled as a network of queues, but a manufacturer does not have to budget for individual server capacity a year or more in advance. Moreover, when a plant faces an overall surge in demand, it can call in workers from other plants, hire temporary workers, pay overtime, or outsource work to contractors. Those actions might break budget forecasts, but manufacturers do not mind when costs go up if the reason is unexpectedly strong demand, since that demand brings an associated increase in revenue. Although DOJ can take at least some analogous actions (e.g., by outsourcing), there is no sense in which unexpected surges of demand that occur at a particular time automatically bring an associated increase in revenue. Moreover, the agency would not be permitted to use any increased revenue for its own operations, but would have to initially return it to Treasury.

treats those individuals. Decisions about “treatment,” many of which are discretionary, begin from the moment that an unauthorized immigrant enters the system. As described in Chapter 4, DHS and other enforcement agents place each person apprehended in one of three main enforcement “pipelines”—administrative return, formal removal, or criminal charges—each option having different implications for the use of DOJ’s marshals, lawyers, judges, courtrooms, and detention facilities. At any stage thereafter, DOJ decisions makers and staff can adapt their procedures and actions to meet the ebb and flow of traffic along any pipeline or route and across geographic regions. In DOJ’s case, the budgeting challenge is magnified by its “downstream” position relative to DHS policies and administrative decisions. These external changes may alter service demands for local DOJ components of the enforcement system quickly, well before the deliberative processes of budgeting and appropriating can be used to adjust resources. In the meantime, adaptive behavior by DOJ policy makers and administrators, at national or local levels, may be the only tool DOJ administrators have to cope with changes in service demand.

In a rigid system, the nonlinearity described above would yield tremendously volatile system behavior. But DOJ personnel and others— lawyers, judges—can adapt and adjust to pressures, at least to some extent. Those in positions of authority (e.g., U.S. attorneys, immigration judges) may have considerable latitude to change operating priorities or practices to respond to otherwise unmanageable queues; others (e.g., U.S. marshals and detention services) have less but still some flexibility. Activity may be shifted from one sector to another to balance workload with resources in various locations. Changes in adjudication methods—decisions to release or detain or application of technology (such as remote televised court proceedings)—can expand capacity. Some adjustments are at the discretion of individual personnel: just as store cashiers, for example, work faster when faced with a long line of impatient customers but are chattier when there is no one behind the current customer. Thus, the average rate at which customers are served (cases are processed) depends on the length of the queue (as well as other aspects of the system).

Components of DOJ that process unauthorized immigrants have been extraordinarily adaptive in this regard. For example, some U.S. attorneys have expanded their capacity to pursue immigration felony cases by deputizing attorneys in DHS’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP) as Special Assistant U.S. Attorneys dedicated to these cases, and in Tucson, the district court, as part of Operation Streamline, tries five defendants at once in a collective proceeding rather than hear cases individually (see Chapter 4). These changes are not evidence of global improvements in productivity. Rather, they are local adaptations made under pressure in

jurisdictions where such adaptation was needed to cope with resource limits.

In addition to such local adaptations and suggesting additional “flex” in the overarching system, DOJ has made increasing use of information and communications technology, such as deploying immigration judges remotely using video conference facilities, to address fluctuations in workloads across regions and increased demands over time.7 Whereas typical service and manufacturing systems might have service rates that flex by ± 25 percent, it appears the immigrant enforcement system may have service rates that flex by larger percentages.

This commonsense adaptation to pressure is generally a good thing; without it, the system may have imploded at times of surging service demand. But what may better serve public policy aims can be a headache for budgeters, because it is hard to anticipate how much service rates will adapt to pressure or how incomplete adaptation will shift the burden around in the queuing network, altering which components of the network have been pushed beyond the “elbow” in the system performance curve described in the preceding section. Simply put, it may be difficult to anticipate the spillover effects of adaptation in one component on another.

Behavioral Adaptation by Potential Unauthorized Immigrants

One obvious example of adaptive behavior by potential unauthorized immigrants is deterrence. The first-order effect of tougher treatment of unauthorized immigrants by either DHS or DOJ is to increase DOJ costs, as a function of more arrests and higher rates of detentions and prosecutions per arrest. In theory though, if increased enforcement successfully deterred illegal immigration, then “demand” would drop as a result, and net costs might go down, not up. But, as noted in Chapter 3, the evidence on deterrence suggests there has been only a small effect of tougher enforcement on the volume of unauthorized immigration.8 Moreover, the recent volume of unauthorized immigration has been large enough that even with a sharp drop in flow and a related drop in apprehensions, the potential decline in DOJ enforcement services demand has been more than offset by the increasing proportion of people appre-

![]()

7For brief descriptions of the joint automated booking system and law enforcement sharing program that contribute to greater productivity for the immigration enforcement function as well as other law enforcement functions of DOJ, see U.S. Department of Justice (2011b).

8We note, however, that empirical findings may not fully capture the deterrent effect of recent enforcement efforts, which coincided with the post-2007 economic downturn, making the effects of deterrence difficult to isolate; and research may underestimate the deterrent effect on some foreign nationals who never decide to migrate, in part, as a result of the high costs of unauthorized migration associated with robust enforcement efforts.

hended who are referred for adjudication. As a result, DOJ’s caseloads have risen rather than fallen with the fall in apprehensions, and at many points the caseloads exceed processing capacity. Thus, the demand for DOJ services is a complicated result of adaptation not only by potential unauthorized immigrants, but also by DHS and DOJ decision makers and administrators, including policies that involve increased “consequences” for violation of immigration laws. Apart from any deterrent effect, adaptive behavior by unauthorized immigrants could affect the amount and distribution of DOJ’s workload costs in several ways, including a “caging effect,” a “balloon effect,” and reactive changes in the mix of immigrants.

Caging Effect. An unintended consequence of tougher border enforcement appears to have been that it has replaced traditional patterns of circular migration with long-term settlement by unauthorized immigrants in the United States (see Chapter 3). Given the number of unauthorized immigrants already in the United States of about 10 million, suppose the number of people seeking to enter for the first time is on the order of 1 million per year. A plausible change in home visitation rates, say, from once every 2 years to once every 4 years, would yield a commensurate decline in attempted reentries from 5 million to 2.5 million each year. This decline would more than offset any increase from other sources in the number of attempted new entries. The effect, other things equal, would be to reduce those subject to enforcement and thus potentially reduce resource requirements.

Balloon Effect. Researchers have long described the effects of immigration enforcement as being similar to squeezing a balloon in one place only to see the air flow to a different location. Would-be border crossers gather information in Mexico about variation along the border in U.S. enforcement efforts and are strategic about where they attempt entry. These shifts are particularly important from a budgeting perspective because the cost to DOJ of an additional crossing varies substantially by sector and because there is a cost to shift personnel and other resources from one sector to another.

For example, the federal district court in Tucson has established a capacity limit of 70 illegal entry felony prosecutions cases per day. So when 10 more people cross in Tucson, their crossing has no effect on the part of DOJ’s costs related to criminal prosecution, even if all 10 are apprehended. In contrast, in El Paso, where there is at least the intent of applying “consequential enforcement” to everyone who is apprehended and the apparent capacity to do so, when 10 more or 10 fewer unauthorized immigrants seek to cross it has direct DOJ budget implications. In this situation, when toughness drives entrants to sectors where average

enforcement costs are lower and where capacities have been “swamped” so they cannot apply additional sanctions, DOJ’s costs can actually go down (see Kleiman, 1993). Of course, if the capacity is merely stressed and not swamped, the opposite can occur because of nonlinearities (as discussed above).9 Regardless of the overall effect on resource requirements, needs may change dramatically in short periods in one or many geographic locations.

Reactive Changes in the Mix of Unauthorized Immigrants. Changes in the kinds of people apprehended also affect DOJ’s costs. For example, if tougher border enforcement makes crossing physically more demanding, it could increase the proportion of unauthorized immigrants who are young males, who are more likely to commit felonies than are other demographic groups. Or if a higher percentage of those apprehended are reentrants or have been previously convicted of other crimes and are therefore more likely to be prosecuted as felons, it would increase DOJ’s cost per immigrant. Also, the mix of Mexicans and non-Mexicans apprehended at the border makes a difference to the workload of immigration courts because non-Mexicans are more likely to appear before immigration judges. So costs may rise even as case volumes fall and vice versa.

Jurisdictional Complexity and Dispersal of Authority

A third challenge to effective DOJ budgeting for immigration enforcement is jurisdictional complexity on at least two levels: by agency and by geography. By agency, complexity derives from the division of responsibility for enforcement between two executive departments, with an additional important role for the federal courts. DHS is the agency primarily responsible for conducting immigration enforcement at the border and in the United States, but DOJ is the agency responsible for conducting immigration removal procedures and criminal trials and for prosecuting people charged with immigration-related crimes. In addition, even within DHS, three separate enforcement agencies (ICE, CBP’s Border Patrol, and CBP’s Office of Field Operations) conduct separate enforcement actions, and all have much discretion in how they enforce immigration policy. As a result, the flow of people to DOJ’s portions of the immigration enforcement system is almost entirely beyond the agency’s control: in addition to

![]()

9Shifting sector-specific demand in a way that shifts demand from a sector with lower utilization to one with higher utilization will generally increase overall waiting and system congestion, because queuing performance curves are convex—at least up to the point at which customers are simply dumped out of the system, which could be one way to characterize what has happened in Tucson.

strictly exogenous factors in the broader immigration system, it depends on policy choices and policy implementation by multiple actors in DHS.

The immigration enforcement system is also geographically complex, as described in Chapter 4. In particular, while DOJ enforcement practices and resource demands are set by federal court districts, DHS practices and spending decisions are made by Border Patrol sectors and ICE field offices, and local law enforcement agencies operate at city, county, and state levels. These various jurisdictional boundaries do not either coincide or nest within each other: for example, there are federal court districts that span multiple field offices’ jurisdictions and vice versa. The Texas border, for example, is split among five Border Patrol sectors and three ICE field offices, with the westernmost sector and field office also encompassing parts of New Mexico.

The lack of one-to-one correspondence between DOJ, DHS, and state and local jurisdictions creates two distinct challenges. First, it greatly complicates the exercise of combining data from DOJ, DHS, state, and local information systems. This complication might be addressed by adding some additional identifier fields to the data records: for example, DHS could label each individual not just by DHS sector but also by DOJ district, state, county, zip code, and other geographic identifiers. Second, beyond the practical issues of data collection and integration, it complicates administration. For example, DHS implemented Operation Streamline first in its Del Rio sector and only later in its El Paso sector, which is also part of its Western District. Indeed, El Paso immigration courts process people from entirely different parts of the country, whose cases are adjudicated in Texas because of the availability of detention spaces there or for other reasons.

To help deal with the system’s complexity and geographic variation, both across the borders and internally, decision-making responsibility is delegated to officials and to field personnel. The U.S. attorneys have broad discretion to set priorities for criminal prosecution, for example. And individual CBP agents working along the border have, for practical reasons, wide latitude in determining how they handle individuals they encounter. These and many other examples of the delegation of decision making result in considerable geographic variation in the way cases are processed (see Chapter 4). This delegation of decision-making authority is a strength of the administrative system, allowing it to adapt to local conditions and learn through experimentation at particular locations and the adoption of innovative practices by other locations. It may also be a necessity. However, for budgeting, such variation and change further complicates the problem of understanding or modeling the system accurately enough to estimate the effects of possible changes in resource levels or uses on its performance.

Exogenous Influences

The budgeting challenges discussed above derive from characteristics of the immigration enforcement system, but many important factors that affect the flow of unauthorized immigrants into and through the system, and thus affect resource requirements, are external to DOJ (and often to DHS). Indeed, as described in Chapter 3, immigration decisions are primarily explained by the opportunities in the potential immigrants’ countries of origin and their destination—the economic “pushes” and “pulls” that include the labor markets at both ends of the migration chain—and by social networks connecting transnational immigrant communities. As the recent U.S. economic downturn and slow recovery illustrates, governments have limited capacity to influence labor markets. And at the macro level, many of the most important factors that affect migration flows are not only external to the immigration enforcement system, but beyond the control of any government action in the United States or abroad. For the United States, for example, the pace of immigration over the last several decades has been driven by the end of the Vietnam War and refugee outflows from Southeast Asia, the Mexican debt crises and peso devaluations in 1982, 1986, and 1994, four U.S. recessions, Cuba’s decision to open the port of Mariel and other exit ports in 1981 and 1994, and a series of civil wars and natural disasters in Central America and the Caribbean, among other factors. Exogenous changes continue to shape immigration flows; many of the more recent influences are discussed in Chapter 3.

In addition to these completely exogenous impacts on the immigration system, demand for enforcement resources also reflects policy changes at the federal, state, and local levels that occur outside of DOJ. Major, or even moderate, shifts in policy—such as increased apprehensions of visa overstayers or systematic changes in the exercise of prosecutorial discretion—can have striking implications for resource needs throughout the immigration enforcement system. Indeed, if the recent downward trend in migration attempts changes and is accompanied by a continued upward trend in “consequences,” the combined effect could be a dramatic surge in demands on DOJ’s components of the enforcement system.

Given the system’s decentralized administration and a degree of autonomy of each “node” in the system, imitative adoption of an initial policy change in one location by those in other locations may at times lead to a cascade of ad hoc, “adaptive” changes throughout the system. Such learning and imitation might occur within DOJ, across its components or sectors, between DOJ and DHS, or across DOJ and DHS components, sectors, and districts.

Although some might hold budget analysts and planners accountable for anticipating such policy shifts, they are treated here as unforesee-

able exogenous events that can create large variances between budgeted and actual costs. That is, they are another reason that budgeting for this system is harder than for many others. Moreover, as documented in Chapter 4 and Appendix A, immigration policy has been volatile, and it is likely to continue changing in light of public expressions of dissatisfaction with the status quo and the lack of a national consensus about the desired results, much less what policies would best achieve them. Indeed, there is sharp conflict between federal and state governments over many aspects of immigration enforcement. Abrupt shifts, uncoordinated actions, and different entities working at cross purposes are very common in this policy area, as in many others.

Budget analysts and planners would need to anticipate the effects of a policy shift not only for DOJ’s activities, but also for those of DHS and even state and local governments to the extent that the latter would affect DOJ’s resource requirements. As discussed in Chapter 4, the need for coordination across entities is widely appreciated in the field, but our discussions with DOJ analysts based in Washington, DC, suggest they do not closely coordinate their budget preparation with DHS or always receive timely information about DHS plans and new initiatives.

Even if there was timely sharing of information about DHS plans and new initiatives, budgets do not emerge from spreadsheets alone; rather, they emerge from a political process that must weigh and measure the sometimes competing needs of components within and across agencies. If providing funds for the work of highly visible border patrols is somehow more politically attractive than funding the work of customs agents or immigration judges, U.S. marshals, or construction of new courtrooms, then temporary or chronic resource imbalances may arise in the system.

Given the difficulty of anticipating change, timing can be important in defining surprises. Analysts must not only anticipate the effects of policy changes, but they also have to have sufficient time to assess the budget implications of those changes. Whether a change in policy—or any other external event—constitutes a true “surprise” could depend on when the change is announced in relation to the budget process and when the change is expected to take effect, as well as whether the budgetary implications of the change are estimable. The likelihood of a budgetary “surprise” rises as the time remaining in the relevant planning cycle diminishes; moreover, the potential for discrepancies between budget estimates and actual needs increases as the quality of information and analytical tools declines. The discussion of data limitations that follows seriously calls into question whether the budgetary effect of a substantial policy change would, in fact, be estimable, given any amount of advance warning.

Limitations in the Available Data

As is true for most public programs, limitations in the available data affect the reliability and accuracy of budget estimates for DOJ immigration enforcement. The data limitations in this area fall into three general categories: poor information about previous and planned inputs, poor information about the cost of activities, and poor information about (or poor understanding of) how changes in inputs and policies affect costs, outputs, and important outcomes.

Poor Information About Previous and Planned Input. Budgeting for an open system in which demand is driven at least partly by external factors is challenging when the environment is dynamic. Certainly, this has been and will be the case for immigration enforcement. Flows and patterns of illegal immigration, changing economic conditions in the United States and elsewhere, and many other factors affect demand. As documented in Chapters 3 and 4, these factors have changed dramatically in relatively short periods in the past; the nature of the environment suggests they will continue to do so. From DOJ’s administrative and operating perspective, “external” factors also include the policies and behavior of the enforcement components overseen by DHS. Information about planned changes in DHS’s policies and practices is often unavailable when DOJ is developing budget estimates, as noted above, and when the Office of Management and Budget and then Congress are reviewing those estimates.

Poor Information About the Cost of Activities. Budgeting requires estimates of average and marginal costs for the activities that will be funded. In some instances, these can be estimated reliably and accurately on the basis of recent history, adjusted for changes in planned inputs where these are known. But costs for some major activities—such as detention or processing of apprehended persons—are also a function of changes in policies and practices that affect the proportions of people released or detained, criminally prosecuted or not, and so on. If facilities reach the limits of their capacity, the marginal costs of housing or transporting an additional unauthorized immigrant may rise rapidly. Thus, cost estimation becomes a major challenge.

Poor Information About the Effects of Changes. It is common in budgeting to look to the history of changes as a simple set of benchmarks for estimating the resource needs of the system: this is the basis for the incremental approach to budgeting described above. For a system whose fundamental character evolves rapidly, such estimates may be unavailable or not useful as benchmarks. In this context, incremental budgeting might

produce a consistent set of estimates over time, but they are unlikely to be accurate as estimates of needed resources.

Information reported by DOJ on enforcement outputs or the outcomes of DOJ’s enforcement activity is very limited. Desired outcomes are, for the most part, either not specified or not measured. The 20072012 DOJ strategic plan (U.S. Department of Justice, 2007) includes only two long-term performance targets related to immigration enforcement: a 2012 target for the Office of the Federal Detention Trustee (OFDT) to hold the increase in average per-day jail cost for federal detention at or below inflation and a 2012 target for the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) to complete 90 percent of priority cases within established time frames. In addition, one of the high-priority goals set in 2010 by the Obama Administration for DOJ was to increase immigration judges by 19 percent by the end of fiscal 2011 so that as DHS criminal alien enforcement activity increased, not less than 85 percent of the immigration court detained cases would be completed within 60 days.

Without meaningful measures of performance relative to the policy objectives of immigration enforcement—such as measures of success in reducing successful illegal entry, or length of stay, or prompt and fair adjudication of status—it is not possible to relate specific activities or resource uses to such enforcement outcomes. DOJ has not attempted to estimate or account for variations in its contribution to the success of policies aimed at reducing efforts of illegal immigration to the United States or to prompt and fair adjudication of cases. Moreover, because these outcomes are a joint product of the activities of two departments and the federal courts, it would be difficult to isolate the effects of DOJ’s activities on the achievement of policy goals from those of other system elements. Development and use of such performance information for planning and budgeting therefore may appropriately be considered a joint or shared responsibility of the two departments, given that each has a major responsibility for the enforcement system’s administration.

Lack of Data on Case Histories

Further confounding even elementary attempts to estimate resource requirements—for DOJ or any other parts of the immigration enforcement system—are notable weaknesses of the data on case histories and, hence, on processing flows rather than events. Counting events is often sufficient for retrospective analysis, e.g., to explain what the costs were last year. (“Where did the money go?” or “How much did these activities cost last year, on average?”) Forecasting future costs when policy or exogenous changes are anticipated requires a different kind of thinking. Answering those “what if?” questions requires some understanding of causal link-

ages (“If this quantity changes, how will that affect other quantities”): those kinds of questions require data systems that are oriented to people and their “careers” of interactions with the system.

At present, analysts lack credible, complete information on the numbers of individuals who enter and exit the system, as well as the numbers of individuals who enter each pipeline in the system and the amount of time they spend in the system, either in total or at any point in the system. At present, a budget analyst would lack sufficient information to track the progress of any individual—or cohort of individuals—through the immigration enforcement system. Given this paucity of useful data, the most rudimentary indicators of the cost of handling additional cases are well beyond reach, let alone any more sophisticated behavioral assessments.

The committee received and analyzed some partial case history data from DHS for individuals apprehended by the agency in (fiscal) 2008-2010. The files were created by combining administrative records for the same person: with some gaps, they show the progress of the case and its final disposition, if that occurred during the period covered by the file, which ended with the first quarter of fiscal 2011. On the basis of our work, we believe that there could soon be the capacity to produce and analyze complete case histories of people moving through the enforcement system. The committee believes this can be accomplished without new data collection: rather, we believe it can be accomplished by the continued progress in integrating DHS information systems and further data sharing with DOJ. The files prepared at the committee’s request demonstrate that complete case histories can be constructed from the existing administrative databases maintained for operating purposes by both departments.

Although the data needed are available now, to produce case history data and analysis useful to inform policy and budget choices will require further work. First, the case histories would have to be completed so that all critical events in administrative databases, and their dates, are included: this task will require combining the new case histories data maintained by DHS with matched administrative records for the same cases in DOJ. Second, personal histories—including basic demographic characteristics and other background information (such as previously recorded apprehensions and encounters with federal immigration officials or other law enforcement and criminal backgrounds) would have to be integrated with the case histories data by matching on personal identifiers.10 On the basis of its examination of the data provided by DHS and discussions with DHS and DOJ staff, the committee believes that it would be feasible—and not a major investment—to combine administra-

![]()

10Over time, those case histories could be extended to include future apprehensions of the same individual and subsequent handling of those cases.

tive records with information on unique individuals, but it would require additional work on the data systems of both departments.

Once such a base of information is available, analysis could reveal, much more clearly than previously available aggregate statistics, how people with different personal characteristics and histories are treated at different points in the system over time and with what outcome (such as removal, return, or relief to stay). As a step to measuring the effects of specific enforcement methods or broader enforcement strategies, planners and budgeters could conduct “what if” analyses to study the probable effects of possible changes in local or national policy and practice through various parts of the enforcement system. For example, an analyst could ask: “If funding for this particular component of the immigration enforcement system—(e.g., immigration judges in specified sectors) is increased, how would it affect: (1) the number of people in detention waiting for proceedings and, hence, the associated numbers and costs for detention; (2) the proportion of undocumented immigrants who are apprehended who will not be detained at all because of a lack of detention capacity; and (3) incentives for those trying to cross in one border sector or another?” Or, an analyst might ask: “What would be the effects on various system components and associated resource requirements of applying the same ‘consequences’ in the San Diego sector that have been applied to similar cases in the Tucson sector?”

If the nonlinearities and interactions of the system can be properly modeled, such “what if” analyses can help analysts, budget planners, and policy makers better understand the probable effects of different methods and strategies, taking account both of their budgetary costs and their marginal or joint contributions to changes in outputs and perhaps, ultimately, to achieving the outcomes sought for immigration enforcement. At a minimum, by highlighting potential “choke points” and other constraints, such analyses can help policy makers identify more cost-effective ways to use limited resources to achieve their policy objectives for immigration enforcement. The value for budgeting of potential future use of case histories data depends on other steps, including improving measures of the aggregate effects of enforcement and decisions about which measures are best to use in assessing the system’s performance.

We began this chapter by distinguishing two basic tasks of budgeting. One task is to estimate future resource requirements to carry out established programs and activities. A second task is to identify and assess alternative ways to use resources that may be more effective in achieving policy goals.

In this chapter, we have suggested why even the first of these tasks will always be difficult for the immigration enforcement system. Budget estimates for this system are subject to substantial error regardless of the approach taken, with implications for the quality of enforcement services and the effectiveness of the system in achieving its legislated purpose. Improvements can be made, however, through better data and analysis. These should reduce errors in estimation. The addition of information about performance and expanded use of case histories may increase the ability to conduct a “what if” analysis of how changes in resource uses may affect other system components and could contribute to changes in performance. This analysis could inform budget choices, improve decisions about where to use budgeted resources, and possibly improve performance.