Wayne J. Katon, M.D.1

INTRODUCTION

Delay of harmful effects of growing older has been called “compression of morbidity” (Fries, 1980), “successful aging” (Rowe and Kahn, 1987), and “healthy aging” (Guralnik and Kaplan, 1989). Both health promotion activities and enhanced management of chronic conditions have been suggested as ways to improve successful or healthy aging (Von Korff et al., 2011). Health promotion activities, such as exercise, healthy diet, weight loss, and cessation of smoking, are believed to potentially enhance successful aging. Given the high prevalence of chronic illness in aging populations, improving guideline-based management of the most common chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, heart disease, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, and depression, would also have a major public health impact in improving successful aging (Mor, 2005). Depression is unique in that it is as common in the general population as these other chronic conditions but also occurs in high prevalence as a comorbid condition (Katon, 2011). Effective treatment of comorbid depression has been found to reduce functional impairment in patients with diabetes (Ell et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2004), heart disease (Lesperance et al., 2007; Rollman et al., 2009), arthritis (Lin et al., 2003), and chronic pain (Kroenke et al., 2009). However, there are major gaps in the recognition and quality

![]()

1Professor and Vice-Chair, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Box 356560, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington.

of treatment of depression in aging populations with chronic medical illness (Katon et al., 2004a).

Patients with chronic medical illness have been found to have two- to threefold higher rates of major depression compared with age- and gender-matched primary care controls (Katon, 2011). Rates of depression among primary care patients are between 5 and 10 percent (Katon and Schulberg, 1992), whereas prevalence rates of depression in patients with chronic medical illnesses, such as diabetes and coronary artery disease, have been estimated to be 12 to 18 percent (Ali et al., 2006) and 18 to 23 percent, respectively (Schleifer et al., 1989; Spijkerman et al., 2005). Rates of depression in complex multicondition aging populations may be as high as 25 percent (McCall et al., 2002).

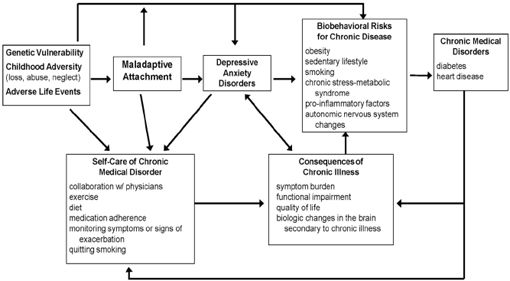

Studies have suggested that there is a bidirectional relationship between depression and such chronic medical illnesses as diabetes, heart disease, and COPD (Figure A-1) (Katon, 2011). Depression often develops in the teenage years or early adulthood. Predisposing factors to depression include genetic factors as well as experiencing childhood adversities, such as the loss of one or both parents, neglect, and abuse (Kendler et al., 2002). Stressful life events in people with these vulnerabilities often precipitate depressive episodes (Caspi et al., 2003). Exposure to childhood adversity also often leads to problems with maladaptive attachment patterns in adult relationships, resulting in lack of social support and problems with interpersonal relationships (Bifulco et al., 2002). Lack of support and interpersonal problems may precipitate and prolong depressive episodes (Bifulco et al., 2002).

Depression in adolescence and early adulthood is associated with three health behaviors that have been estimated to cause 40 percent of premature mortality in the United States: obesity, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle (Katon et al., 2010c). Psychobiological changes that have been shown to be associated with depression, such as increased cortisol levels, sympathetic nervous system dysregulation, and increased proinflammatory factors, are likely to add to maladaptive health factors in increasing the risk of premature development of chronic illness (Katon, 2011).

Once chronic illness develops, comorbid depression is associated with poor self-care (DiMatteo et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2004) and increased risk of adverse outcomes (Lin et al., 2009; van Melle et al., 2004). As Figure A-1 shows, patients with comorbid depression and chronic medical illness often have problems collaborating with physicians and are less likely to adhere to self-care regimens (diet, cessation of smoking, exercise, and taking medications as prescribed) (Katon, 2011). These maladaptive patterns lead to a higher risk of medical complications, increased symptom burden, and worsening function, which can then in turn precipitate or worsen depressive episodes.

Extensive epidemiological data have shown that, after controlling for

FIGURE A-1 Bidirectional interaction between depression and chronic medical disorders.

SOURCE: Adapted and reprinted from Biological Pyschiatry, 54, Wayne J. Katon, Clinical health services and relationship between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness, 216–226, 2003, with permission from Elsevier.

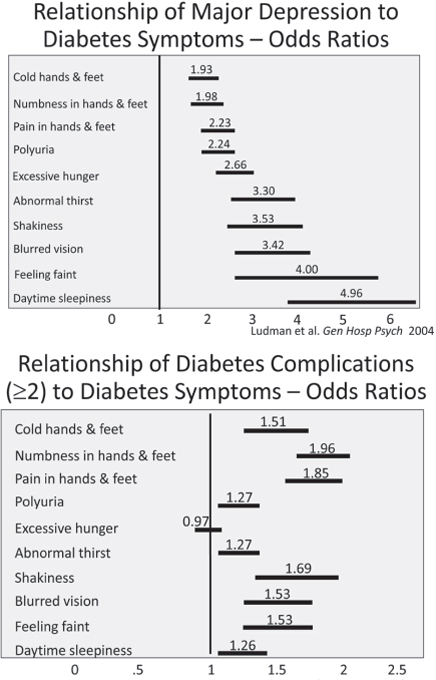

sociodemographic factors and severity of medical illness, patients with comorbid depression and chronic medical illnesses, such as diabetes, coronary heart disease (CHD), COPD/asthma, and cancer, also have a higher medical symptom burden (Katon et al., 2007), additive functional impairment (Von Korff et al., 2005), higher medical costs (Simon et al., 2005; Sullivan et al., 2002), increased complication and hospitalization rates (Davydow et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2010; van Melle, et al., 2004), and increased mortality (Egede et al., 2005; Katon et al., 2005b; Lin et al., 2009, 2010; van Melle et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005). Figure A-2 describes the results of comorbid depression on diabetes symptom burden from a 5-year prospective study of approximately 4,800 predominately type 2 diabetes patients enrolled in a large health care system in Washington state. After controlling for sociodemographic factors and severity of medical illness, comorbid major depression in these patients was a stronger predictor of 10 symptoms on a diabetes symptom scale than was number of diabetes complications or HbA1c level (Ludman et al., 2004). In addition, in this cohort of approximately 4,800 patients with diabetes, comorbid depression was associated with more than additive functional impairment (Von Korff et al., 2005), and approximately 50 to 70 percent higher medical costs (Simon et al., 2005). Over the 5-year period, after controlling for sociodemographic factors and the baseline severity of medical illness, patients with comorbid depression and diabetes compared with those with diabetes alone had a 24 percent greater risk of macrovascular complications (Lin et al., 2010), a 36 percent greater risk of microvascular complications (Lin et al., 2010), a twofold increased risk of incident foot ulcers (Williams et al., 2010), a twofold increased risk of dementia (Katon et al., 2010b), and a 50 percent greater risk of mortality (Katon et al., 2005b; Lin et al., 2009), as seen in Table A-1.

In considering ways to improve diagnosis and treatment of people with depression and chronic illnesses, it is important to recognize that these are often aging populations. The prevalence of chronic medical illness increases with each decade of life, and approximately 40 percent of Medicare beneficiaries have two or more chronic medical illnesses (Hoffman et al., 1996). Aging populations with depression have been found to be significantly less likely to utilize mental health services compared with younger depressed patients (Unützer et al., 2000). This is likely to be due to increased stigma regarding mental illness in aging populations, less access due to insurance issues (i.e., many private mental health specialists do not accept Medicare payments), decreased mobility due to chronic medical illnesses and functional decline, and less knowledge about mental illness in this population (Unützer et al., 2000; Van Citters and Bartels, 2004). Among the patients whose depression is recognized in primary care, few receive guideline-level pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy (Druss, 2004; Katon et al., 2004a).

FIGURE A-2 Relationship of depression and diabetes symptoms.

SOURCE: Ludman et al., 2004.

TABLE A-1 Relationship of Depression and Diabetes Symptoms

| Minor Depression | Major Depression | |

| Microvascular Complications | 1.05 (0.83, 1.33) | 1.33 (1.08, 1.65) |

| Macrovascular Complications | 1.32 (0.99, 1.75) | 1.38 (1.08, 1.78) |

| Mortality (All Cause[s]) | 1.23 (0.94, 1.61) | 1.53 (1.19, 1.96) |

| Foot Ulcers | 1.32 (0.74, 2.35) | 1.99 (1.22, 3.24) |

| Dementia | – | 2.69 (1.77, 4.07) |

SOURCE: Katon, 2011.

PUBLIC HEALTH PLATFORMS TO

ENHANCE CARE OF DEPRESSION

Given the high prevalence of depression in patients with chronic medical illness and the decreased likelihood of accessing mental health services, it is important to consider possible “public health platforms” that could improve the likelihood of accurate diagnosis and treatment of people with depression and chronic medical illness.

Because of the lack of access to traditional mental health services in aging medically ill populations, several recent reports have advocated either developing community-based outreach mental services for frail elderly with multiple chronic illnesses or integrating mental health services into primary care. These recent publications include the surgeon general’s report on mental health (HHS, 1999), the report by the Administration on Aging (2001), and the summary of the subcommittee of the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (Bartels, 2003).

COMMUNITY-BASED PUBLIC HEALTH PLATFORMS

A recent meta-analysis that evaluated face-to-face psychological services for adults ages 65 and older with mental illness identified 14 studies, including 5 randomized controlled trials (Van Citters and Bartels, 2004). An interesting finding from this systematic review compared studies that used “gatekeeper models” of recruitment, such as meter readers, building supervisors, or utility workers, with those using medical or social work personnel. Those using gatekeepers tended to identify more socially isolated elderly, such as those living alone and people more often widowed or divorced (Van Citters and Bartels, 2004). However, individuals identified by either gatekeepers or medical/mental health personnel had similar mental and physical health services needs.

Of the 14 studies reviewed in this meta-analysis, 2 found support for using gatekeepers, such as utility workers, to identify socially isolated aging

populations with mental illness (Florio and Raschko, 1998; Florio et al., 1998). Other researchers are piloting work with community-based organizations to educate and screen populations for depression, such as churches or adult day care centers (Chung et al., 2010). In all, 12 studies (of which only 5 were randomized controlled trials) found that home- and community-based treatment of psychiatric symptoms were associated with improved psychological status (Van Citters and Bartels, 2004). All five randomized trials (and a more recent sixth trial) reported home-based interventions were associated with improved depressive symptoms, and one reported improved overall psychological symptoms (Banerjee et al., 1996; Blanchard et al., 2002; Ciechanowski et al., 2004; Llewellyn-Jones et al., 1999; Rabins et al., 2000). This review will focus on the evidence from the randomized controlled trials, which focused on depression in socially isolated, often medically frail elderly.

Many communities have developed visiting home-based services for aging patients with disabilities that limit mobility. These services are often provided by either social workers or nurses. These frail elderly have been found to have a high prevalence of major depression due to social isolation, chronic pain, and lack of access to medical and mental health services (McCall et al., 2002).

Research has shown that depression screening that is connected to an organized treatment program, increasing exposure to evidenced-based depression treatment, can significantly improve outcomes of these patients (Banerjee et al., 1996; Blanchard et al., 2002; Ciechanowski et al., 2004; Llewellyn-Jones et al., 1999; Rabins et al., 2000).

A recent study randomized 138 patients ages 60 and over with minor depression or dysthmia to the Program to Encourage Active, Rewarding Lives for Seniors (PEARLS) or usual care (Ciechanowski et al., 2004). The PEARLS intervention consisted of problem-solving treatment, social and physical activation, and potential recommendations to patients’ physicians regarding antidepressant medications (Ciechanowski et al., 2004). The intervention was provided by social workers who were supervised by psychiatrists employed by Aging and Disability Services, a county-funded home visiting program for frail elderly. Social workers screened clients with the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) during routine in-home visits or during telephone calls. Positive scores then led to screening with a structured psychiatric interview, and clients with either minor depression or dysthmia were offered randomization to the study intervention compared with usual care. This intervention significantly increased the percentage of patients with at least a 50 percent decrease in depressive symptoms or remission of depressive symptoms (Ciechanowski et al., 2004). Intervention patients compared with usual care controls also were found to have greater improvement in health-related quality of life and emotional well-being.

This home-based PEARLS program was also recently tested in 80 patients with comorbid depression and epilepsy (Ciechanowski et al., 2010). Patients with epilepsy have extremely high rates of depression and markedly higher rates of suicide compared with other medical populations (Ciechanowski et al., 2010). The PEARLS intervention was delivered by master’s-level counselors and compared with usual primary care and was found to significantly decrease depressive symptoms and suicidality over a 12-month period (Ciechanowski et al., 2010).

Rabins et al., examined in a randomized controlled trial the effect of a multidisciplinary care protocol and nurse-based outreach to 298 seniors living in public housing (Rabins et al., 2000). Among the six housing sites, residents in three buildings were randomized to receive the intervention and three buildings were randomized to usual care. The intervention group had significantly more improvement in overall general psychological symptoms as well as depression symptoms compared with controls (Rabins et al., 2000). The intervention had two key components: (1) identification of potential patients by gatekeepers (managers, social workers, janitors) and (2) evaluation and treatment by a psychiatric nurse supervised by a psychiatrist. A limitation of this protocol was the lack of a standardized treatment.

Llewellyn-Jones and colleagues examined the effect of a multidisciplinary treatment program provided primarily by a general practitioner in 220 elderly people living in a residential facility (Llewellyn-Jones et al., 1999). The intervention group had significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms compared with controls (Llewellyn-Jones et al., 1999). The shared care intervention program involved multidisciplinary consultation and collaboration, training of several practitioners and caretakers in detection and management of depression, and depression-related health education and activity programs for residents. The control group received routine care.

Blanchard and colleagues tested a screening and multidisciplinary multimodal intervention in 96 elderly people living at home with minor or major depression (Blanchard et al., 2002). The intervention involved a psychiatrist interview, presentation of results to a multidisciplinary geriatric psychiatry team, and a nurse interventionist working closely with a general practitioner to implement recommendations made by the team (Blanchard et al., 2002). Controls received standard or usual care. The intervention group showed greater improvement in depressive symptoms than controls at 3 months. Limitations include lack of control for baseline factors and a lag between initial assessment and the start of the intervention.

Banerjee and colleagues tested a home-based intervention for depression with 69 people ages 65 and over who received home care and were depressed (Banerjee et al., 1996). Members of the intervention group received a package of care that was developed by a community psychogeriatric team

and implemented by one psychiatrist. Controls received care as usual by a general practitioner. Patients in the intervention group were significantly more likely to have recovered from depression at 6 months compared with controls (Banerjee et al., 1996).

The home-based programs for frail elderly that utilized nurses as case managers and/or geriatric multidisciplinary teams often also evaluated medical conditions and geriatric risk factors, such as potential for falls and poor nutrition.

PRIMARY CARE PLATFORMS

Large observational studies have found that severity of medical illness was a predictor of chronicity of depression symptoms in aging populations with chronic medical illness (Kennedy et al., 1991). Therefore, a key research question is whether evidenced-based psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatment approaches that have been found to be efficacious in depressed patients without chronic medical illness would be as effective in those with depression and comorbid conditions, such as diabetes, CHD, or cancer.

Several systematic reviews have found that antidepressants are more effective than placebo in patients with depression and chronic medical illness (Gill and Hatcher 2000; van der Feltz-Cornelis et al., 2010). Systematic reviews have also found that evidence-based psychotherapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, were more effective than supportive, nonspecific theories in treatment of depression in patients with comorbid medical illness (van der Feltz-Cornelis et al., 2010). Most of these trials of antidepressant medication or psychotherapy were small, with fewer than 100 patients, and they often selected patients with less severe medical illness and limited psychiatric comorbidities (Gill and Hatcher, 2000; van der Feltz-Cornelis et al., 2010).

A key question has been how to deliver evidence-based depression treatment to the large populations of patients with chronic conditions across a range of severity. Since most patients with comorbid depression and chronic medical illness are seen by primary care physicians and/or medical specialists, integrating depression services into these systems of care is a logical way to deliver mental health services to larger populations.

Collaborative care models have been shown to be effective in improving the quality of depression care and depression outcomes compared with usual primary care in a wide range of primary care populations, from adolescent (Asarnow et al., 2005) through geriatric populations (Unützer et al., 2002). Collaborative care programs integrate an allied health professional, such as a nurse or social worker, into primary care to support behavioral and pharmacological treatments initiated by primary care providers

(Gilbody et al., 2006). These allied health professionals are trained to provide patient education about common mental disorders, proactively track clinical symptoms using such rating scales as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), support adherence to medications, and provide brief evidence-based forms of psychotherapy, such as problem-solving, cognitive behavioral, or interpersonal therapy (Gilbody et al., 2006). Collaborative care teams also usually include a consulting psychiatrist who provides caseload-focused supervision for a panel of patients treated in primary care. The psychiatrist advises primary care providers about diagnostic and therapeutic approaches if patients are not improving with initial treatments, and they may provide in-person consultation for selected patients with persistent symptoms or diagnostic complexity. Collaborative care models have been tested in over 40 primary care–based randomized controlled trials and have been shown to be more effective than usual primary care in improving quality of depression care and depression and functional outcomes for up to 2 years (Gilbody et al., 2006).

In recent years collaborative care approaches have also been tested in patients with depression and chronic medical illness. Three collaborative care trials have been completed in primary care patients with comorbid depression and diabetes (Ell et al., 2010; Katon et al., 2004b; Williams et al., 2004). In each of these trials, intervention patients were provided with a psychiatrically supervised case manager who offered an initial choice of problem-solving treatment (PST) or antidepressant medication (Ell et al., 2010; Katon et al., 2004b; Williams et al., 2004). Patients were treated with stepped care principles so if they did not respond to therapy, a medication could be added, or if they did not respond to an initial medication, another medication could be tried or PST could be added. Collaborative care was shown to improve quality of depression care, depression outcomes, functioning, and patient satisfaction with care compared with usual care (Ell et al., 2010; Katon et al., 2004b; Williams et al., 2004). Moreover, collaborative care compared with usual care was shown to be associated with savings in total medical costs in each of these three randomized controlled trials (Hays et al., 2011; Katon et al., 2006; Simon et al., 2007).

The IMPACT trial randomized 1,801 aging patients with major depression and/or dysthymia from 8 health care organizations to collaborative care and usual care. These patients had a mean of four chronic medical illnesses. Compared with usual primary care, collaborative care was associated with improved quality of depressive care and functional and depression outcomes over a 2-year period (Katon et al., 2005a). In IMPACT, the cost of collaborative care was offset by savings in medical costs over a 2-year period (Katon et al., 2005a). In one of the above diabetes depression collaborative care trials and in the IMPACT trial, long-term costs were examined and showed continued cost savings for up to

5 years compared with usual primary care (Katon et al., 2008a; Unützer et al., 2008).

Two trials of collaborative care have also been shown to improve quality of care and outcomes in cardiac patients compared with usual care. Rollman and colleagues tested a telephone-based depression collaborative care model delivered by nurses working with patients’ primary care providers to enhance antidepressant medication treatment, patient education, and behavioral activation (Rollman et al., 2009). In 302 postcoronary bypass graft patients with comorbid depression, this intervention was associated with significant improvements in depression symptoms and mental health functioning over an 8-month period compared with usual care (Rollman et al., 2009). Davidson and colleagues tested a depression collaborative care model that gave patients a choice of starting treatment with pharmacotherapy or problem-solving treatment in 157 patients persistently depressed for 3 months after an acute coronary event (Davidson et al., 2010). Collaborative care compared with usual primary care was shown to significantly improve depressive symptoms over a 1-year period (Davidson et al., 2010).

Four collaborative care trials have also been tested in patients with comorbid depression and cancer (Ell et al., 2008; Fann et al., 2009; Kroenke et al., 2010; Strong et al., 2008). Fann and colleagues examined results from the 215 patients with depression and cancer enrolled in the IMPACT trial (Fann et al., 2009). Patients randomized to collaborative care had significant improvements in depressive symptoms and functioning and enhanced quality of life compared with those randomized to usual care (Fann et al., 2009). Strong and colleagues randomized 200 patients with comorbid depression and cancer to collaborative care and usual care (Strong et al., 2008). Collaborative care involved a nurse-delivered intervention that included a choice of either problem-solving treatment or antidepressant medication provided by the patient’s primary care physician. Patients in the intervention group have improved depression, anxiety, and fatigue outcomes compared with usual care over a 12-month period (Strong et al., 2008).

Kroenke and colleagues tested a collaborative care approach for 405 patients with cancer with either comorbid depression, significant persistent pain, or both (Kroenke et al., 2010). The intervention was a telephone-based care management program that provided education about pain and depression, and a stepped medication algorithm for both pain and depression based on patient symptoms measured on standard scales (Kroenke et al., 2010). Nurses were supervised weekly by both pain and psychiatric specialists and medication recommendations were communicated by nurse managers to patients’ primary care physicians. Intervention patients had significant decreases in both pain and depressive symptoms compared with usual care controls over a 12-month period.

Ell and colleagues randomized 472 low-income, predominately Hispanic patients with cancer and comorbid major depression or dysthymia to a collaborative care intervention and usual care (Ell et al., 2008). Intervention patients had up to 12 months of access to a depression clinical specialist (supervised by a psychiatrist) who provided education, structured psychotherapy, and maintenance/relapse prevention support (Ell et al., 2008). The supervising psychiatrist prescribed antidepressant medication for patients preferring medication initially or for those not responding to psychotherapy. Intervention patients had significantly greater quality of depression care and had improved depressive and functional outcomes over 12 months compared with usual care patients (Ell et al., 2008).

A recent study examined the effectiveness of collaborative care for 249 patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and comorbid depression (Pyne et al., 2011). An off-site HIV depression team (a registered nurse depression care manager, a pharmacist, and a psychiatrist) provided depression care for 12 months backed by a web-based discussion support system (Pyne et al., 2011). Intervention patients were found to have significantly more depression-free days and less HIV symptom severity over a 12-month period compared with usual care controls (Pyne et al., 2011).

Although quality improvement trials have shown that care management approaches aimed at improving care of single illnesses, such as depression, diabetes, and coronary heart disease, can improve outcomes, many patients have multiple chronic illnesses, and these patients have the most problems with quality of care and adverse outcomes and are very costly to medical systems. For example, among Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes, depression or congestive heart failure, approximately 60 to 70 percent have three or more other chronic medical conditions (Partnership for Solutions National Program Office, 2001). Patients with three or more chronic conditions (approximately 32 percent of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 to 69 have three or more conditions increasing to 52 percent in the 80 to 84 year subgroup) (Schafer et al., 2010) have been found to account for approximately 89 percent of Medicare costs (Partnership for Solutions National Program Office, 2001). A new multicondition collaborative care intervention program has been shown to improve depression, glucose, blood pressure and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and functional outcomes compared with usual care in patients with poorly controlled diabetes and/or coronary heart disease and comorbid depression (Katon et al., 2010a). This program trained diabetes nurses to enhance treatment of diabetes, coronary heart disease, and depression and provided weekly supervision of nurses by both a psychiatrist and a primary care physician (Katon et al., 2010a). Cost-effectiveness analysis from this new multi-condition collaborative care study also found a high likelihood of total outpatient cost savings over a 2-year period (Katon et al., unpublished).

Two other models of care have also been tested in older patients with multiple chronic illnesses. Neither of these trials required the patients to have comorbid depression, but they did include intervention components that could be used to address depression if present. The GRACE model tested a home-based care management intervention by a nurse practitioner and a social worker who collaborated with the primary care physician and a geriatrics interdisciplinary team (Counsell et al., 2007). This intervention was guided by 12 core protocols for common geriatric conditions. A randomized trial that included 951 adults ages 65 years or older showed that, compared with usual primary care, the GRACE intervention was associated with improvements in general health, vitality, social functioning, and mental health but not activities of daily living or mortality (Counsell et al., 2007). The guided care model tested the effect of a nurse working in partnership with the patient’s primary care physician for patients with multiple chronic conditions (Boult et al., 2011). The intervention included comprehensive geriatric assessment, evidence-based care planning, monitoring of symptoms and adherence, transitional care, coordination of health care professionals, support for self-management, support for family caregivers, and enhanced access to community services (Boult et al., 2011). Guided care was found to reduce home health care but had little effect on the use of other health services and did not improve patient functional outcomes compared with usual primary care (Boult et al., 2011).

Based on the above successful trials, the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association have recently recommended screening for depression by medical systems of care. However, studies have shown that screening for depression alone does not improve outcomes; screening must be connected with organized approaches to care to improve outcomes.

COMMUNITY-BASED ALTERNATIVE

APPROACHES TO DEPRESSION

Many community organizations offer aerobics and other exercise classes as well as classes on yoga, meditation, and other potentially therapeutic modalities. Although these types of interventions are generally accepted as helping psychological well-being in relatively healthy populations, it is less clear that these treatments are effective for clinical depression. There is an emerging literature describing exercise interventions for depression and several recent systematic reviews, but the research is much more limited on the effectiveness of yoga and meditation.

Exercise could potentially have a therapeutic effect on depression because of beneficial effects on neurogenesis, endorphins, and serotonin drive (Krogh et al., 2011). A recent Cochrane review of exercise as a treatment for depression found that many studies had significant methodological

flaws; when analyses were restricted to more robust trials, there was a moderate but nonsignificant beneficial effect of exercise compared with nonexercise control groups (Mead et al., 2008). A critique of these studies is that, although many of the enrolled patients had mild depression based on a depression rating scale score, most would not meet criteria for major depression or dysthymia. A more recent systematic review included only studies in which a clinical diagnosis of depression was made. That review found a short-term mild significant effect of exercise on depression compared with nonexercise control groups (Krogh et al., 2011). However, there was limited evidence of a beneficial long-term effect, with the trials lasting more than 10 weeks no longer showing significant effects.

A key critique of exercise trials has been the potential lack of generalizability to populations of depressed patients. Symptoms of depression, such as lack of motivation and energy, will probably limit the ability of many patients to enroll in these studies. Thus, even if exercise has a modest effect in ameliorating symptoms of depression, it is likely to have only mild effects on decreasing prevalence of serious depression in populations.

Several small trials have suggested that yoga and meditation may have beneficial effects on depression. These trials need replication in larger numbers of patients meeting criteria for major depression or dysthymia.

HEALTH POLICY CHANGES THAT COULD IMPROVE

QUALITY AND OUTCOMES OF DEPRESSION CARE

Berwick has emphasized that major organizational changes will be necessary for medical care systems to adapt existing primary care and medical specialty services to optimize care of patients with chronic illnesses, such as depression or diabetes (Berwick et al., 2003). These changes include investing in clinical information systems, such as registries to help track the quality and outcomes of care in specific populations; linking these systems to medical records; and designing decision support systems that will develop and implement treatment guidelines in a timely manner (Berwick et al., 2003). Organizational changes will also be needed to create delivery systems, such as depression management teams to implement more frequent systematic follow-up and monitoring of outcomes, promote integration of mental health specialty care into primary care, and develop self-management tool-kits for patients and providers.

Economic incentives and regulatory changes will be needed to implement these costly changes in care. As Berwick has emphasized, “For most organizations, investment on this scale is a strategic issue and will only be undertaken if the market—employers and government purchasers, principally and consumers secondarily—permits and rewards these strategies” (Berwick et al., 2003).

Key “demand side” levers include increasing community, consumer, and employer demand for integrating evidence-based changes in systems of care, aligning financial models of care to defray the costs of reorganizing health services to provide “collaborative care, and developing new Health Plan Employer Data Information Set (HEDIS) depression performance criteria that evidence suggests are linked with improved outcomes” (Katon and Seelig, 2008b). Increasing demand will necessitate education of consumer groups, employers, and insurers about cost-effective models to improve depression care, including information on how these models may decrease overall medical costs in patients with comorbid medical illnesses, such as diabetes (Katon and Seelig, 2008b). Katon and Selig have reported that “several of the research groups involved in dissemination of collaborative care are working with consumer groups, such as the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), and the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, to lobby insurers to develop payment systems for collaborative care” (Katon and Seelig, 2008b). An innovative approach would be to have insurers help pay for the cost of training and changes in systems of care to help defray initial investment costs, since health insurers are likely to realize cost savings with collaborative care programs. Employers have also recognized the adverse impact of poor quality of care of chronic illnesses like depression on the workforce in terms of decreased productivity, absenteeism, and disability (Stewart et al., 2003). Recent research suggests that employed patients with depression who have poor adherence to acute and continuation phase antidepressant treatment were 39 and 46 percent more likely, respectively, to file short-term disability claims (Burton et al., 2007). Wang and colleagues have shown that an innovative program combining depression screening with telephone-based collaborative depression care improved both depression outcomes and work productivity compared with usual care when implemented in a large corporation (Wang et al., 2007). Based on research demonstrating the effectiveness of collaborative care, the National Business Group on Health has recently strongly recommended implementation of payment for evidence-based collaborative care programs for depression (Finch and Phillips, 2005).

In primary care systems, quality improvement efforts to integrate depression collaborative care programs have been hindered by lack of billing codes for the depression care manager in-person and telephone visits and time for caseload supervision by a psychiatrist. Development of Medicare billing codes for these crucial components of collaborative care could enhance dissemination efforts of this evidence-based model. The six major insurers in Minnesota are collaborating in a quality improvement project (DIAMOND program) for depression in primary care and have developed payment models for the above components of collaborative care; early reports

suggest high levels of patient recovery similar to randomized trials of collaborative care (Korsen and Pietruszewski, 2009).

Changes in health insurance that provide higher payments for enhanced outcomes of populations with chronic illnesses such as depression could also enhance dissemination of collaborative care. Most collaborative care trials have enhanced clinical response to depression treatment (percentage of patients with at least 50 percent decrease in depressive symptoms) by 15 to 30 percent (Gilbody et al., 2006). However, lack of financial incentives for clinical improvement as well as difficulty billing for the mental health services utilized in collaborative care has made investment in integrating depression care managers and supervising psychiatrists difficult for systems of care.

Another key policy change that could enhance dissemination of collaborative care is to develop HEDIS performance criteria that research suggests are “tightly linked” to enhanced outcomes (Kerr et al., 2001). The current criteria include documenting the percentage of patients receiving at least 3 visits in the 90 to 120 days after diagnosis and initiation of treatment in primary care as well as the percentage of patients adhering to antidepressant medications at 3 and 6 months (Druss, 2004; NCQA, 2000). These criteria have not been shown by researchers to be linked to enhanced outcomes. Moreover only 20 percent of patients across multiple systems of care actually receive the three visits that HEDIS criteria suggest are important (Druss, 2004). Many patients who are taking their antidepressant at 6 months are still on the small dosage that was started, which makes few patients better. Most patients need upward titration of medication based on measurement of depressive symptom response, and they often need a second or third medication trial before an optimum type and dosage of antidepressant is found. A performance criterion tightly linked to outcomes could be the percentage of patients with less than a 50 percent decrease in symptoms 12 weeks after initiating antidepressant treatment who receive intensification of depression treatment, such as increased dosage of medication, change to a second medication, or referral for a mental health consultation. Payments to health organizations that report improvement in percentage of patients with at least a 50 percent improvement in their initial level of depressive symptoms at 3 and 6 months could also increase motivation for systems of care to integrate evidence-based models of care.

PREVENTION OF DEPRESSION IN PATIENTS

WITH CHRONIC MEDICAL ILLNESSES

Preventive interventions to decrease incidence of depression in patients with chronic medical illness have been developed in recent years. Rovner and colleagues tested the effect of problem-solving therapy (PST) in patients

with macular degeneration in one eye and a recent change in vision due to macular disease in the other eye (Rovner et al., 2007). The rationale for this study was data suggesting high rates of depression in patients who developed this irreversible disease. Patients randomized to PST and usual care were found to have significantly lower incidence of depression and were less likely to have decreased function (Rovner et al., 2007). de Jonge and colleagues tested a multifaceted nurse intervention aimed at preventing depression in 100 patients with diabetes or rheumatological disease (de Jonge et al., 2009). At 1-year follow-up, lower rates of incident depression were found in intervention versus usual care patients (36 versus 63 percent) (de Jonge et al., 2009). Pitceathly and colleagues tested a brief psychological intervention versus usual care in a large sample of patients recently diagnosed with cancer (Pitceathly et al., 2009). Although at 12 months there were no intervention versus control differences in incident depression in the overall group (intent-to-treat analysis), among patients with a high risk of depression, a significant intervention effect was found (Pitceathly et al., 2009). Robinson and colleagues tested antidepressants versus PST versus placebo to prevent depression in 176 patients with a recent stroke (Robinson et al., 2008). Over the 12-month period, patients receiving placebo were more likely to develop depression compared with those receiving antidepressants or PST (Robinson et al., 2008).

The above studies are promising, but more studies are needed. A key question will be to determine whether it is cost-effective to provide preventive interventions to only high-risk groups, such as those with a prior history of anxiety and/or depression. Our research group has found in a 5-year longitudinal study of approximately 3,000 patients with type 2 diabetes that over 80 percent who were depressed at 5-year follow-up either had minor or major depression at baseline (Katon et al., 2009). These data and the results of the above studies suggest preventive treatment of high-risk populations may be most cost-effective.

COMMUNITY APPROACHES TO IMPROVING

TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION

One exciting community-based effort that could be implemented to disseminate collaborative care would be for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovations to develop a dissemination project to test the cost-effectiveness of collaborative care in a large region of the United States.

Given the evidence that depression increases medical costs by 50 to 100 percent and that collaborative care often is associated with total medical cost savings, this would seem like a logical next step to decrease Medicare and Medicaid costs. This project could build on the effective training model used in the DIAMOND project that has improved quality and outcomes

of depression care among primary care patients in Minnesota (Korsen and Pietruszewski, 2009).

A second exciting community-based project would involve testing methods to improve mental health care for patients in federally qualified primary care clinics and the medical care of patients with chronic mental illness enrolled in community mental health systems. Funding from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has helped stimulate new models of care with funding for demonstration projects for these two systems to enhance coordination of mental health and physical health care. This funding has led to unique partnerships in which primary care physicians and advanced registered nurse practitioners from federally funded primary care clinics have established clinics in community mental health centers, and, in turn, mental health practitioners from community mental health centers have established clinics in federally funded primary care clinics.

CONCLUSION

In summary, depression and chronic medical illnesses are associated with functional decline in aging populations. Depression is two to three times more common in people with chronic conditions (Katon, 2011), but there are major gaps in recognition and quality of care for this affective illness. Interventions have been developed and integrated into both community-based public health platforms and primary care platforms and have been shown in randomized controlled trials to improve depression and functional outcomes. Several of the primary care–based collaborative care intervention programs have also shown a high likelihood of total medical cost savings over a 2-year period. Key changes in reimbursement for these new models of care will need to be completed to enhance dissemination effects.

REFERENCES

Ali, S., M.A. Stone, J.L. Peters, M.J. Davies, and K. Khunti. 2006. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with Type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetic Medicine 23(11):1165–1173.

AoA (Administration on Aging). 2001. Older Adults and Mental Health: Issues and Opportunities. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

Asarnow, J.R., L.H. Jaycox, N. Duan, A.P. LaBorde, M.M. Rea, P. Murray, M. Anderson, C. Landon, L. Tang, and K.B. Wells. 2005. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association 293(3):311–319.

Banerjee, S., K. Shamash, A.J. Macdonald, and A.H. Mann. 1996. Randomised controlled trial of effect of intervention by psychogeriatric team on depression in frail elderly people at home. British Medical Journal 313(7064):1058–1061.

Bartels, S. J. 2003. Improving system of care for older adults with mental illness in the United States. Findings and recommendations for the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11(5):486–497.

Berwick, D.M., B. James, and M.J. Coye. 2003. Connections between quality measurement and improvement. Medical Care 41(1 Supplemental):I30–I38.

Bifulco, A., P.M. Moran, C. Ball, and A. Lillie. 2002. Adult attachment style. II: Its relationship to psychosocial depressive-vulnerability. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37(2):60–67.

Blanchard, E.B., L. Keefer, A. Payne, S.M. Turner, and T.E. Galovski. 2002. Early abuse, psychiatric diagnoses and irritable bowel syndrome. Behaviour Research Therapy 40(3): 289–298.

Boult, C., L. Reider, B. Leff, K.D. Frick, C.M. Boyd, J.L. Wolff, K. Frey, L. Karm, S.T. Wegener, T. Mroz, and D.O. Scharfstein. 2011. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: Results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine 171(5):460–466.

Burton, W.N., C.Y. Chen, D.J. Conti, A.B. Schultz, and D.W. Edington. 2007. The association of antidepressant medication adherence with employee disability absences. American Journal of Managed Care 13(2):105–112.

Caspi, A., K. Sugden, T.E. Moffitt, A. Taylor, I.W. Craig, H. Harrington, J. McClay, J. Mill, J. Martin, A. Braithwaite, and R. Poulton. 2003. Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 301(5631):386–389.

Chung, B., L. Jones, E.L. Dixon, J. Miranda, K. Wells; Community Partners in Care Steering Council. 2010. Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: Planning community partners in care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 21(3):780–795.

Ciechanowski, P., E. Wagner, K. Schmaling, S. Schwartz, B. Williams, P. Diehr, J. Kulzer, S. Gray, C. Collier, and J. LoGerfo. 2004. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association 291(13):1569–1577.

Ciechanowski, P., N. Chaytor, J. Miller, R. Fraser, J. Russo, J. Unützer, and F. Gilliam. 2010. PEARLS depression treatment for individuals with epilepsy: A randomized controlled trial. Epilepsy & Behavior 19(3):225–231.

Counsell, S.R., C.M. Callahan, D.O. Clark, W. Tu, A.B. Buttar, T.E. Stump, and G.D. Ricketts. 2007. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association 298(22):2623–2633.

Davidson, K.W., N. Rieckmann, L. Clemow, J.E. Schwartz, D. Shimbo, V. Medina, G. Albanese, I. Kronish, M. Hegel, and M.M. Burg. 2010. Enhanced depression care for patients with acute coronary syndrome and persistent depressive symptoms: Coronary psychosocial evaluation studies randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine 170(7):600–608.

Davydow, D.S., J.E. Russo, E. Ludman, P. Ciechanowski, E.H. Lin, M. Von Korff, M. Oliver, and W.J. Katon. 2011. The association of comorbid depression with intensive care unit admission in patients with diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Psychosomatics 52(2):117–126.

de Jonge, P., F.B. Hadj, D. Boffa, C. Zdrojewski, Y. Dorogi, A. So, J. Ruiz, and F. Stiefel. 2009. Prevention of major depression in complex medically ill patients: Preliminary results from a randomized, controlled trial. Psychosomatics 50(3):227–233.

DiMatteo, M.R., H.S. Lepper, and T.W. Croghan. 2000. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of Internal Medicine 160(14):2101–2107.

Druss, B.G. 2004. A review of HEDIS measures and performance for mental disorders. Managed Care 13(6 Supplemental Depression):48–51.

Egede, L.E., P.J. Nietert, and D. Zheng. 2005. Depression and all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality among adults with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care 28(6):1339–1345.

Ell, K., B. Xie, B. Quon, D.I. Quinn, M. Dwight-Johnson and P.J. Lee. 2008. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 26(27):4488–4496.

Ell, K., W. Katon, B. Xie, P.J. Lee, S. Kapetanovic, J. Guterman, and C.P. Chou. 2010. Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 33(4):706–713.

Fann, J.R., M.Y. Fan, and J. Unützer. 2009. Improving primary care for older adults with cancer and depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 24(Suppl 2):S417–S424.

Finch, R.A., and K. Phillips. 2005. An employer’s guide to behavioral health services: A roadmap and recommendations for evaluating, designing, and implementing behavioral health services. Center for Prevention and Health Services, National Business Group on Health. Washington, DC.

Florio, E.R., and R. Raschko. 1998. The gatekeeper model: Implications for social policy. Journal of Aging and Social Policy 10(1):37–55.

Florio, E.R., J.E. Jensen, M. Hendryx, R. Raschko, and K. Mathieson. 1998. One-year outcomes of older adults referred for aging and mental health services by community gatekeepers. Journal of Case Management 7(2):74–83.

Fries, J.F. 1980. Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. New England Journal of Medicine 303(3):130–135.

Gilbody, S., P. Bower, J. Fletcher, D. Richards, and A.J. Sutton. 2006. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine 166(21):2314–2321.

Gill, D., and S. Hatcher. 2000. Antidepressants for depression in medical illness. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews (4):CD001312.

Guralnik, J.M., and G.A. Kaplan. 1989. Predictors of healthy aging: Prospective evidence from the Alameda County study. American Journal of Public Health 79(6):703–708.

Hays, J., W. Katon, K. Ell, P.J. Lee, and J.J. Guterman. 2011. Cost effectiveness analysis of collaborative care management for major depression among low-income, predominately Hispanics with diabetes: assessment in psychiatry. Tenth Workshop on Costs and Assessment in Psychiatry. Venice, Italy: Mental Health Policy and Economics. March 14.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hoffman, C., D. Rice, and H.Y. Sung. 1996. Persons with chronic conditions. Their prevalence and costs. Journal of American Medical Association 276(18):1473–1479.

Katon, W.J. 2003. Clincial health services and relationship between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biological Pyschiatry 54:216–226.

Katon, W.J. 2011. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 13(1):7–23.

Katon, W., and H. Schulberg. 1992. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry 14(4):237–247.

Katon, W.J., G. Simon, J. Russo, M. Von Korff, E.H. Lin, E. Ludman, P. Ciechanowski, and T. Bush. 2004a. Quality of depression care in a population-based sample of patients with diabetes and major depression. Medical Care 42(12):1222–1229.

Katon, W.J., M. Von Korff, E.H. Lin, G. Simon, E. Ludman, J. Russo, P. Ciechanowski, E. Walker, and T. Bush. 2004b. The Pathways Study: A randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 61(10):1042–1049.

Katon, W.J., M. Schoenbaum, M.Y. Fan, C.M. Callahan, J. Jr. Williams, E. Hunkeler, L. Harpole, X.H. Zhou, C. Langston, and J. Unützer. 2005a. Cost-effectiveness of improving primary care treatment of late-life depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 62(12):1313–1320.

Katon, W.J., C. Rutter, G. Simon, E.H. Lin, E. Ludman, P. Ciechanowski, L. Kinder, B. Young, and M. Von Korff. 2005b. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 28(11):2668–2672.

Katon, W., J. Unützer, M.Y. Fan, J.W. Jr. Williams, M. Schoenbaum, E.H. Lin, and E.M. Hunkeler. 2006. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care 29(2):265–270.

Katon, W., E.H. Lin, and K. Kroenke. 2007. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. General Hospital Psychiatry 29(2):147–155.

Katon, W.J., J.E. Russo, M. Von Korff, E.H. Lin, E. Ludman, and P.S. Ciechanowski. 2008a. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care 31(6):1155–1159.

Katon, W.J., and M. Seelig 2008b. Population-based care of depression: Team care approaches to improving outcomes. Journal of Occupation and Environmental Medicine 50(4):459–467.

Katon, W., J. Russo, E.H. Lin, S.R. Heckbert, P. Ciechanowski, E.J. Ludman, and M. Von Korff. 2009. Depression and diabetes: Factors associated with major depression at five-year follow-up. Psychosomatics 50(6):570–579.

Katon, W.J., E.H. Lin, M. Von Korff, P. Ciechanowski, E.J. Ludman, B. Young, D. Peterson, C.M. Rutter, M. McGregor, and D. McCulloch. 2010a. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. New England Journal of Medicine 363(27): 2611–2620.

Katon, W.J., E.H. Lin L.H. Williams, P. Ciechanowski, S.R. Heckbert, E. Ludman, C. Rutter, P.K. Crane, M. Oliver, and M. Von Korff. 2010b. Comorbid depression is associated with an increased risk of dementia diagnosis in patients with diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25(5):423–429.

Katon, W., L. Richardson, J. Russo, C.A. McCarty, C. Rockhill, E. McCauley, J. Richards, and D.C. Grossman. 2010c. Depressive symptoms in adolescence: The association with multiple health risk behaviors. General Hospital Psychiatry 32(3):233–239.

Katon, W.J., J. Russo, and E. Lin. Unpublished. Cost-effectiveness of a multi-condition collaborative care intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. Kendler, K., C. Gardner, and C.A. Prescott. 2002. Toward a comprehensive developmental model for major depression in women. American Journal of Psychiatry 159(7):1133–1145.

Kennedy, G.J., H.R. Kelman, and C. Thomas. 1991. Persistence and remission of depressive symptoms in late life. American Journal of Psychiatry 148(2):174–178.

Kerr, E.A., S.L. Krein, S. Vijan, T.P. Hofer, and R.A. Hayward. 2001. Avoiding pitfalls in chronic disease quality measurement: A case for the next generation of technical quality measures. American Journal of Managed Care 7(11):1033–1043.

Korsen, N., and P. Pietruszewski. 2009. Translating evidence to practice: Two stories from the field. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 16(1):47–57.

Kroenke, K., M.J. Bair, T.M. Damush, J. Wu, S. Hoke, J. Sutherland, and W. Tu. 2009. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association 301(20):2099–2110.

Kroenke, K., D. Theobald, J. Wu, K. Norton, G. Morrison, J. Carpenter, and W. Tu. 2010. Effect of telecare management on pain and depression in patients with cancer: A randomized trial. Journal of American Medical Association 304(2):163–171.

Krogh, J., M. Nordentoft, J.A. Sterne, and D.A. Lawlor. 2011. The effect of exercise in clinically depressed adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 72(4):529–538.

Lesperance, F., N. Frasure-Smith, D. Koszycki, M.A. Laliberté, L.T. van Zyl, B. Baker, J.R. Swenson, K. Ghatavi, B.L. Abramson, P. Dorian, and M.C. Guertin; CREATE Investigators. 2007. Effects of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy on depression in patients with coronary artery disease: The Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) trial. Journal of American Medical Association 297(4):367–379.

Lin, E.H., W. Katon, M. Von Korff, L. Tang, J.W. Jr. Williams, K. Kroenke, E. Hunkeler, L. Harpole, M. Hegel, P. Arean, M. Hoffing, R. Della Penna, C. Langston, and J. Unützer; IMPACT Investigators. 2003. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association 290(18):2428–2429.

Lin, E.H., W. Katon, M. Von Korff, C. Rutter, G.E. Simon, M. Oliver, P. Ciechanowski, E.J.

Ludman, T. Bush, and B. Young. 2004. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care 27(9):2154–2160.

Lin, E.H., S.R. Heckbert, C.M. Rutter, W.J. Katon, P. Ciechanowski, E.J. Ludman, M. Oliver, B.A. Young, D.K. McCulloch, and M. Von Korff. 2009. Depression and increased mortality in diabetes: Unexpected causes of death. Annals of Family Medicine 7(5):414–421.

Lin, E.H., C.M. Rutter, W. Katon, S.R. Heckbert, P. Ciechanowski, M.M. Oliver, E.J. Ludman, B.A. Young, L.H. Williams, D.K. McCulloch, and M. Von Korff. 2010. Depression and advanced complications of diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 33(2):264–269.

Llewellyn-Jones, R.H., K.A. Baikie, H. Smithers, J. Cohen, J. Snowdon, and C.C. Tennant. 1999. Multifaceted shared care intervention for late life depression in residential care: Randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 319(7211):676–682.

Ludman, E. J., W. Katon, J. Russo, M. Von Korff, G. Simon, P. Ciechanowski, E. Lin, T. Bush, E. Walker, and B. Young. 2004. Depression and diabetes symptom burden. General Hospital Psychiatry 26(6):430–436.

McCall, N.T., P. Parks, K. Smith, G. Pope, and M. Griggs. 2002. The prevalence of major depression or dysthymia among aged Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 17(6):557–565.

Mead, G.E., W. Morley, P. Campbell, C.A. Greig, M. McMurdo, and D.A. Lawlor. 2008. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews (4):CD004366.

Mor, V. 2005. The compression of morbidity hypothesis: A review of research and prospects for the future. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53(9 Suppl):S308–S309.

NCQA (National Center for Quality Assurance). 2000. The State of Managed Care Quality 2000. Washington, DC: National Center for Quality Assurance.

Partnership for Solutions National Program Office. 2001. Chronic Conditions: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Pitceathly, C., P. Maguire, I, Fletcher, M. Parle, B. Tomenson, and F. Creed. 2009. Can a brief psychological intervention prevent anxiety or depressive disorders in cancer patients? A randomised controlled trial. Annals of Oncology 20(5):928–934.

Pyne, J.M., J.C. Fortney, G.M. Curran, S. Tripathi, J.H. Atkinson, A.M. Kilbourne, H.J. Hagedorn, D. Rimland, M.C. Rodriguez-Barradas, T. Monson, K.A. Bottonari, S.M. Asch, and A.L. Gifford. 2011. Effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in human immunodeficiency virus clinics. Archives of Internal Medicine 171(1):23–31.

Rabins, P.V., B.S. Black, R. Roca, P. German, M. McGuire, B. Robbins, R. Rye, and L. Brant. 2000. Effectiveness of a nurse-based outreach program for identifying and treating psychiatric illness in the elderly. Journal of American Medical Association 283(21):2802–2809.

Robinson, R.G., R.E. Jorge, D.J. Moser, L. Acion, A. Solodkin, S.L Small, P. Fonzetti, M. Hegel, and S. Arndt. 2008. Escitalopram and problem-solving therapy for prevention of poststroke depression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association 299(20):2391–2400.

Rollman, B.L., B.H. Belnap, M.S. LeMenager, S. Mazumdar, P.R. Houck, P.J. Counihan, W.N. Kapoor, H.C. Schulberg, and C.F. Reynolds III. 2009. Telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association 302(19):2095–2103.

Rovner, B.W., R.J. Casten, M.T. Hegel, B.E. Leiby, and W.S. Tasman. 2007. Preventing depression in age-related macular degeneration. Archives of General Psychiatry 64(8):886–892.

Rowe, J.W., and R.L. Kahn 1987. Human aging: Usual and successful. Science 237(4811): 143–149.

Schafer, I., E.C. von Leitner, G. Schön, D. Koller, H. Hansen, T. Kolonko, H. Kaduszkiewicz, K. Wegscheider, G. Glaeske, and H. van den Bussche. 2010. Multimorbidity patterns in the elderly: a new approach of disease clustering identifies complex interrelations between chronic conditions. PLoS One 5(12):e15941.

Schleifer, S.J., M.M. Macari-Hinson, D.A. Coyle, W.R Slater, M. Kahn, R. Gorlin, and H.D. Zucker. 1989. The nature and course of depression following myocardial infarction. Archives of Internal Medicine 149(8):1785–1789.

Simon, G.E., W.J. Katon, E.H. Lin, E. Ludman, M. VonKorff, P. Ciechanowski, and B.A. Young. 2005. Diabetes complications and depression as predictors of health care costs. General Hospital Psychiatry 27(5):344–351.

Simon, G.E., W.J. Katon, E.H. Lin, C. Rutter, W.G. Manning, M. Von Korff, P. Ciechanowski, E.J. Ludman, and B.A. Young. 2007. Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment among people with diabetes mellitus. Archives of General Psychiatry 64(1):65–72.

Spijkerman, T., P. de Jonge, R.H. van den Brink, J.H. Jansen, J.F. May, H.J. Crijns, and J. Ormel. 2005. Depression following myocardial infarction: First-ever versus ongoing and recurrent episodes. General Hospital Psychiatry 27(6):411–417.

Stewart, W.F., J.A. Ricci, E. Chee, S.R. Hahn, and D. Morganstein. 2003. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. Journal of American Medical Association 289(23):3135–3144.

Strong, V., R. Waters, C. Hibberd, G. Murray, L. Wall, J. Walker, G. McHugh, A. Walker, and M. Sharpe. 2008. Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): A randomised trial. Lancet 372(9632):40–48.

Sullivan, M., G. Simon, J. Spertus, and J. Russo. 2002. Depression-related costs in heart failure care. Archives of Internal Medicine 162(16):1860–1866.

Unützer, J., G. Simon, T.R. Belin, M. Datt, W. Katon, and D. Patrick. 2000. Care for depression in HMO patients aged 65 and older. Journal of American Geriatrics Society 48(8):871–878.

Unützer, J., W. Katon, C.M. Callahan, J.W. Jr. Williams, E. Hunkeler, L. Harpole, M. Hoffing, R.D. Della Penna, P.H. Noël, E.H. Lin, P.A. Areán, M.T. Hegel, L. Tang, T.R. Belin, S. Oishi, and C. Langston; IMPACT Investigators. Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment. 2002. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association 288(22):2836–2845.

Unützer, J., W.J. Katon, M.Y. Fan, M.C. Schoenbaum, E.H. Lin, R.D. Della Penna, and D. Powers. 2008. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. American Journal of Managed Care 14(2):95–100.

Van Citters, A.D., and S.J. Bartels. 2004. A systematic review of the effectiveness of community-based mental health outreach services for older adults. Psychiatric Services 55(11):1237–1249.

van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M., J. Nuyen, C. Stoop, J. Chan, A.M. Jacobson, W. Katon, F. Snoek, and N. Sartorius. 2010. Effect of interventions for major depressive disorder and significant depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry 32(4):80–395.

van Melle, J.P., P. de Jonge, T.A. Spijkerman, J.G. Tijssen, J. Ormel, D.J. van Veldhuisen, R.H.

van den Brink, and M.P. van den Berg. 2004. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine 66(6):814–822.

Von Korff, M., W. Katon, E.H. Lin, G. Simon, E. Ludman, M. Oliver, P. Ciechanowski, C. Rutter, and T. Bush. 2005. Potentially modifiable factors associated with disability among people with diabetes. Psychosomatic Medicine 67(2):233–240.

Von Korff, M., W.J. Katon, E.H. Lin, P. Ciechanowski, D. Peterson, E.J. Ludman, B. Young, and C.M. Rutter. 2011. Functional outcomes of multi-condition collaborative care and successful aging. British Medical Journal 343:d6612.

Wang, P.S., G.E. Simon, J. Avorn, F. Azocar, E.J. Ludman, J. McCulloch, M.Z. Petukhova, and R.C. Kessler. 2007. Telephone screening, outreach, and care management for depressed workers and impact on clinical and work productivity outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association 298(12):1401–1411.

Williams, J.W., Jr., W. Katon, E.H. Lin, P.H. Nöel, J. Worchel, J. Cornell, L. Harpole, B.A. Fultz, E. Hunkeler, V.S. Mika, and J. Unützer; IMPACT Investigators. 2004. The effectiveness of depression care management on diabetes-related outcomes in older patients. Annals of Internal Medicine 140(12):1015–1024.

Williams, L.H., C.M. Rutter, W.J. Katon, G.E. Reiber, P. Ciechanowski, S.R. Heckbert, E.H. Lin, E.J. Ludman, M.M. Oliver, B.A. Young, and M. Von Korff. 2010. Depression and incident diabetic foot ulcers: A prospective cohort study. American Journal of Medicine 123(8):748–754.

Zhang, X., S.L. Norris, E.W. Gregg, Y.J. Cheng, G. Beckles, and H.S. Kahn. 2005. Depressive symptoms and mortality among persons with and without diabetes. American Journal of Epidemiology 161(7):652–660.